Page 1 :

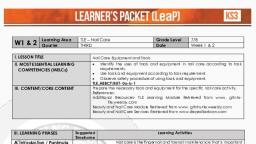

1015, , Cosmetics fro, 44. Cosmetics from Marine Sources, , Elena M. Balboa, Enma Conde, M. Luisa Soto, Lorena Pérez-Armada, Herminia Domínguez, , The application of marine resources for the formulation of cosmetics has been known for centuries., Marine organisms produce unique compounds,, which are not found in terrestrial sources, to, provide protection against hard environmental, conditions. They have been used both to confer:, , �, , In this chapter, the major functional and biological activities of components isolated from, marines sources, including micro and macroorganisms and with special emphasis on algae, are, reviewed in relation to their application to cosmetics. Both the traditionally used compounds, and fractions and those isolated and characterized, in recent years are presented., , 44.1 Scenario of Marine Sources, in the Cosmetic Industry ...................... 1015, 44.2 Cosmetics:, Definition and Regulations .................. 1016, , 44.4 Target Organs, and Cosmetics Delivery Systems ............ 1018, 44.5 Components of Cosmetics ....................., 44.5.1 Active Compounds, in Cosmetics.............................., 44.5.2 Excipients ................................., 44.5.3 Additives .................................., , 1019, 1019, 1019, 1019, , 44.6 Major Functions, of Some Marine Components, in Cosmetics and Cosmeceuticals .......... 1020, 44.6.1 Physicochemical, and Technological Properties...... 1020, 44.6.2 Biological Activities ................... 1023, 44.7 Treatments, Based on Marine Resources .................., 44.7.1 Firming ...................................., 44.7.2 Cellulite ...................................., 44.7.3 Hair Growth Disorders................, , 1029, 1030, 1030, 1032, , 44.8 Products Based on Marine Resources .... 1032, 44.9 Conclusions ......................................... 1033, References................................................... 1033, , 44.1 Scenario of Marine Sources in the Cosmetic Industry, In recent years, health concerns and the demand for natural products have provided incentive for research on, the abundant and alternative sources for novel ingredients and additives. Cosmetic industries, also influenced, by consumers’ preferences, have been increasingly incorporating natural ingredients into different products., However, the natural cosmetic market still represents, a smaller fraction in relation to conventional cosmetics [44.1, 2]., , Terrestrial plant-derived constituents are gaining, popularity [44.3], but the marine environment is a richer, source of both biological and chemical diversity [44.4]., Probably induced by the environmentally extreme conditions, marine organisms possess the capacity to produce molecules with unique chemical and structural, features, which warrant a variety of potent and selective biological actions. Marine resources represent, an underexploited source of highly diverse valuable, , Part G | 44.1, , �, , Physicochemical functional properties to the, cosmetic product, such as texture, emulsifying, properties or color,, Bioactive properties, including remineralizing,, emollient, hydrating, antioxidant, sunscreening, among others., , 44.3 Cosmeceuticals .................................... 1017

Page 2 :

1016, , Part G, , Application of Marine Biotechnology, , compounds [44.4–6] with potential applications in nutraceuticals and cosmetics [44.7–9]., Micro and macroalgae are established on the market for face and skin care products, such as anti-aging, and regenerant creams, refreshing products, emollients,, anti-irritants, sun protection, and hair care products., Components from cultivated microalgae are commercially available [44.10]. Seaweed resources have undergone successive periods of over-exploitation and, neglect, but macroalgae have traditionally been used as, a source of food and medicines, have been included in, cosmetic formulations, and have played a major role in, the development of spa products [44.11]. However, less, than 1% of the identified species are used in pharmacy,, food, and in cosmetology., In addition to macro and microalgae, providing vitamins, minerals, proteins, and amino acids,, sugars, lipids, terpenoids, polyphenols, polysaccharides, pigments, and enzymes, different marine sources, , have been considered for their potential applications in cosmetics and cosmeceuticals. Fish is an, excellent source of gelatin and collagen; corals and, crustaceans can provide diguanosine tetraphosphate,, chitin, chitosan, and astaxanthin, and sea mud and, sea salts have cosmetic applications [44.12]. Most, of these active agents can be found in already, marketed products [44.4] with a variety of functions [44.13]. Recent progress in cosmeceutical applications of marine- derived bioactive substances, including antioxidants, growth factors, peptides, antiinflammatory, and pigment lightening agents, has been, published [44.12]., This chapter presents general aspects on cosmetics,, emphasizing on the potential of marine sources to provide components with a variety of functions, including, technological and biological actions. The most recent, innovation in this field, i. e., active cosmetics or cosmeceutical products, are also presented., , Part G | 44.2, , 44.2 Cosmetics: Definition and Regulations, Cosmetics have been applied from ancient times in, many civilizations for artistic, beautifying, protective, cleansing, and ceremonial purposes [44.14]. In, order to avoid negative impacts on the consumers’, health and to warrant the safety of the products,, regulatory controls are established on the different, markets, although the legislation applied to cosmetic, products differs among countries. The major normative obstacles faced by the cosmetic industries include the different restrictions in the use of the ingredients, the distinct classifications of the cosmetics, and the varied labeling requirements [44.15]. The, International Nomenclature of Cosmetic Ingredients, (INCI) tries to unify the nomenclature in order to, facilitate the adaptation of the products to different, markets., The need for an international harmonization on, the status and safety requirements of cosmetics products and their ingredients has been claimed since, their safety assessment is based on scientific and, epidemiologic knowledge and also on their regulatory status [44.16]. Comparative studies of the regulatory features in different countries impacting on, the manufacture and sale of cosmetic products, such, as: cosmetic definition, licensing, labeling, safety substantiation, stability studies, and legal authority, are, available [44.17–19]., , In the major world markets, cosmetics are regulated, according to two general models:, i) A wide definition of cosmetics and the safety of, the products is based on a few lists of ingredients, (positive, prohibited, or restricted), followed in the, European Union and Japan, although in this latter area another category of cosmetics (quasi-drugs), has been established., ii) A more limited definition of cosmetics, with few restrictions on ingredients and safety tests carried out, by the manufacturers [44.17], followed in the USA, and Canada approaches this model, including a list, of prohibited or restricted ingredients., The Cosmetic Products Regulation (EC) No., 1223/2009 [44.20] has replaced the European Directive, 76/768/EEC [44.21]. It was dictated with the purpose of, guaranteing the safety of the cosmetic products and to, facilitate their marketing. This regulation is applicable, with full effect since July 2013 and reinforces product, safety considering the latest technological developments. The term cosmetic product refers to any substance or mixture intended to be placed in contact with, the external parts of the human body (epidermis, hair, system, nails, lips, and external genital organs) or with, the teeth and the mucous membranes of the oral cavity

Page 3 :

Cosmetics from Marine Sources, , before marketing. The FD&C Act defines cosmetics, as articles intended to be rubbed, poured, sprinkled,, or sprayed on, introduced into, or otherwise applied to, the human body for cleansing, beautifying, promoting, attractiveness, or altering the appearance without affecting the body’s structure or functions. Among the, products included are skin creams, lotions, perfumes,, lipsticks, fingernail polishes, eye and facial makeup, preparations, shampoos, permanent waves, hair colors, and deodorants, as well as any substance intended, for use as a component of a cosmetic product. The, products not included in this definition are regulated, as medicines. The intermediate category of cosmetics, intended to treat, cure, mitigate, treat or prevent disease, or those affecting the structure or functions of, the human body, are not specifically regulated. Among, the products that are drugs and cosmetics are anticaries toothpastes, suntanning lotions to protect against, sunburn, antiperspirants that are also deodorants, and, antidandruff shampoos [44.17]., , 44.3 Cosmeceuticals, Like cosmetics, cosmeceuticals are applied topically, but differ in that they contain potent ingredients such, as vitamins, phytochemicals, enzymes, antioxidants, essential oils, : : : that can deliver nutrients and influence, biological functions to promote healthy skin [44.12,, 13]. Cosmeceutical science is a new branch aimed at, utilizing the resources of the natural environment to obtain efficient products [44.22]. The term cosmeceutical,, formed from the words cosmetic and pharmaceutical,, refers to cosmetic products that have drug-like benefits that enhance or protect the appearance of the, human body [44.23–25]. These products lie between, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals and they are mediumvolume/medium-value products that offer lower risk, and a quicker potential return on investment than, the high-risk high-reward pharmaceutical market. The, value of the cosmeceutical market has been increasing, and it is likely that this trend will continue [44.8]., Cosmeceuticals meet consumer demands for higher efficacy and have become the fastest-growing segment, of the personal care industry [44.13, 23, 26], converting it in the area of dermatology with a more rapid, commercial expansion; the number of new products introduced yearly onto the market is superior than that, of pharmaceuticals [44.23]. The global market value, for marine skin care products was estimated in 15% of, , the cosmetics industry. For marine resources the world, market value for cosmetics was one third of that for, pharmaceuticals [44.7]., Despite the relatively recent appearance of this, concept, over 400 suppliers and manufacturers of cosmeceutical products have been estimated. Amer and, Maged [44.27] classified the products in the cosmeceutical market into four major categories: nonbleaching, agents, antioxidants, peptides, and growth factors. The, market estimations project increases in the demand of, cosmeceutical ingredients. Annual growth rates ranging from 4�25% and 4�10% have been reported for, the periods 2002–2007 and 2007–2012, the injectables, and age-defying products being the most dynamic segments, especially in emerging economies [44.13]., Because of their unique position as neither cosmetics nor pharmaceuticals, no specific regulation exists for, these products [44.13]. Depending on the regulations, of different countries, a group of products can be considered as cosmetic, therapeutic goods, or drug [44.28]., Since the main concern for functional products is safety, and efficacy, it is likely that legislation covering pharmaceuticals will change to include nutraceuticals and, cosmeceuticals to make efficacy claims. Consumers, are often exposed to product information that is not, scientifically sound or backed by rigorous clinical stud-, , 1017, , Part G | 44.3, , with an exclusively or mainly purpose of cleaning perfuming, changing their appearance, protecting, keeping, them in good condition, or correcting body odors. This, regulation includes skin whitening-products, anti-wrinkle products, and products with nanomaterials., In the USA cosmetics are regulated by the Food and, Drug Administration (FDA), and the two most important laws pertaining to cosmetics are the Federal Food,, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C) and the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act (FP&LA). The FD&C Act defines, two main categories of products: cosmetics and drugs,, including the specific subcategory of over-the-counter, (OTC) drugs, which can be sold without prescription., The definition of products as cosmetics or drugs depends on their intended use, which is established on, the basis of claims made about the product. Cosmetic, products and ingredients are not subject to FDA premarket approval authority, with the exception of color, additives, and cosmetic firms are responsible for substantiating the safety of their products and ingredients, , 44.3 Cosmeceuticals

Page 4 :

1018, , Part G, , Application of Marine Biotechnology, , Part G | 44.5, , ies since the multitude of cosmeceutical products are, not specifically regulated [44.17, 23, 28]. Appropriate, controls on the safety of products, consumer protection, the extent of regulatory definition, market fairness, and inconsistency between countries have been, suggested [44.28]. Dermatologists should familiarize, themselves with the available products and assess their, quality before recommending cosmeceuticals to their, patients [44.13, 29, 30]. For practical applications and, to effectively bring a new material to the marketplace,, the viewpoints of many different agents should be, considered, including: environmentally sustainable production, performance of the ingredients, confirmation, of the mechanisms of action, quality assurance, regulations in markets around the world; and adequacy, of supply to fulfill market demand with competitive, pricing [44.31]., Recent trends in cosmeceutical development include skin protection from radiation and oxidative damage and the discovery of bioactives with the ability to, scavenge free radicals and to prevent aging [44.32]., Particular focus is given to nonirritating ingredients to, , develop safer naturally-derived products [44.27], with, components from plants and marine organisms, particularly those pure and uncontaminated. One example, are the Antarctic and Southern Ocean seaweeds and, marine microalgae, which show great potential due, to their adaptation to survive under stressing osmotic, pressure and temperature conditions, resulting in increased phycocolloid and polyunsaturated fatty acids, contents [44.33]. Recent studies have addressed the, screening of bioactive compounds from cold [44.34], and tropical waters [44.9, 35]. The complex matrix of, cosmetics usually contains a high number of ingredients and emulsions. Nanoemulsions have attracted, considerable attention in recent years as potential vehicles for the controlled delivery of bioactives because, of their technological advantages to improve the availability and efficacy of lipophilic bioactives and to avoid, changes during storage [44.36]. Nutricosmetics are another type of product than combine the cosmetic effect, with nutritional supplements that can support the function and the structure of the skin, but they are not, considered in the present chapter., , 44.4 Target Organs and Cosmetics Delivery Systems, The skin is the main objective of cosmetic treatments,, the other target organs for cosmetic products are hair, and nails. Skin forms the interface between the human body and the environment, and is made up of, three distinct layers: the epidermis, the dermis, and the, hypodermis. The epidermis represents a physical, biochemical, and immunological barrier. The outermost, layer of the epidermis is the stratum corneum, a continuous layer of protein-enriched cells embedded in an, intercellular matrix enriched in non-polar lipids and organized as lamellar lipid layers [44.37]. It is responsible, for the prevention of the loss of water and electrolytes,, immune defense, and protection against ultraviolete, (UV) radiation and oxidative damage and it is also capable of withstanding mechanical forces and preventing, toxic substances from penetrating the skin., The changes in this epidermal barrier can alter the, appearance and the functions of the skin. Skin undergoes aging mainly as a consequence of genetic and, external factors; UV irradiation from the sun causes ox-, , idative damage and is the primary environmental factor, causing skin aging and increasing the risk of cutaneous, neoplasms [44.38, 39]. Whereas some symptoms, such, as skin laxity or dyschromia, are observed on the surface, the origin is in deeper layers: the dermis and, subcutaneous tissues. The penetration routes of drugs, into the skin include the hair follicles, interfollicular, sites, and through corneocytes and lipid bilayer membranes of the stratum corneum [44.40, 41]., Traditionally, most skin treatments are applied topically. Semisolid ointments or emulsions are the primary, active delivery systems and the biphasic nature of, emulsions allows the placement of actives based on solubility and stability [44.42]. Novel skin care methods, target multiple aging mechanisms by utilizing functional active ingredients in combination with innovative, delivery systems to increase stratum corneum permeability for cosmetic formulations and novel delivery, systems, such as lipid systems, nanoparticles, microcapsules, : : : [44.43].

Page 5 :

Cosmetics from Marine Sources, , 44.5 Components of Cosmetics, , 1019, , 44.5 Components of Cosmetics, The general composition of a cosmetic includes an, active ingredient, some excipients, thickening agents,, additives, preservatives, colorants, and perfumes., , these agents can be classified into antioxidants and, antimicrobials., , The active ingredient is the main substance, or substances, which confer the required activity to the cosmetic, i. e., the tensioactive in a shampoo, the colorant or pigment in a nail polish, or the moisturizers, (glycerin, lactic acid, or urea) in a hand cream. It, will determine the function of the cosmetic and its, classification., , Antioxidants, Their function is to prevent oxidation of fats and oils, and the active principles present in the cosmetic formulations. Oxidative rancidity of fats and oils is caused, by the degradation by oxygen in the air and occurs, in a series of chain reactions involving free radicals., Oxidized fats become yellowish in color and the undesirable odors produced impair the cosmetic. Depending, on their mechanism of action, different categories of antioxidants are established:, , 44.5.2 Excipients, , �, , 44.5.1 Active Compounds in Cosmetics, , 44.5.3 Additives, Preservatives, Preservatives are added to prevent or delay alterations in cosmetics, at least until the expiration, date. According to the modifications to be prevented,, , �, �, �, , Antimicrobials, Antimicrobials prevent and protect the cosmetic product from microbial contamination (bacteria and fungi)., Their addition is required to avoid contamination and, growth of pathogenic germs over some threshold values that could lead to both deterioration of the product, (turbidity, presence of molds, . . . ) and to health damage (skin infections). Among those frequently used are:, nipasol (propyl p-hydroxybenzoate), nipagyn (methyl, p-hydroxybenzoate), triclosan (2,4,40 -trichloro-20 -hydroxy diphenyl ether), dowicyl 200 (Quaternium15), and imidazolidinyl-urea (1,10 -methylenebis and, alkyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride (ADBAC)., Some cosmetics do not require additional preservatives, such as those containing an antiseptic ingredient,, i. e., ethyl alcohol, and those sold in sealed ampoules, in, this case the protection is restricted to the period when, the cosmetic is closed., Perfumes and Colorants, Perfume and colorant compounds are added with the, function of providing a pleasant odor and color to the, , Part G | 44.5, , Excipients are the vehicle ingredients with the function, of dissolving or dispersing the active agents and other, cosmetic ingredients. It is essential to choose them correctly, since they determine and control the delivery and, effectiveness of the cosmetic in the targeted area, as, well as the cosmetic form and presentation to the end, user. The same cosmetic could be presented in different, forms if different excipients are used. The most used excipients are water, alcohol, glycerin, acetone, vaseline,, and lanoline., The main purpose of stabilizers is to disperse the, additives, thicken the fluid, and maintain the stability, of the cosmetic during its lifetime. Thickeners, such, as polymers and methyl cellulose, increase the viscosity of the formula. Humectants avoid dehydration by, binding water; among the most frequent are glycerine,, propylene glycol, and sorbitol. Chelating agents form, complexes by binding with undesirable ions present in, the formula, which could interfere with the properties, of the cosmetic. pH modifiers are added to adjust the, pH level close to the values of the skin. Citric, tartaric,, or lactic acids are used to acidify the media and triethanolamine to raise the pH. Suspending agents, such, as tensioactives, are used to improve the solubilization, of some active ingredients, i. e., the dispersion of oily, perfumes in aqueous solutions., , Reducing agents, they become readily oxidized,, preventing the oxidation of the active compounds;, ascorbic acid and thiourea are examples of this type., Blocking agents that stop the oxidation chain without being consumed, i. e., butylated hydroxytoluene, (BHT) and tocopherols (vitamin E)., Synergistic agents increase the effectiveness of, some antioxidants, i. e., citric acid and tartaric acid., Chelating agents form complexes with metal ions, that can act as catalysts for the oxidative processes;, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) is one of, the most used.

Page 6 :

1020, , Part G, , Application of Marine Biotechnology, , final cosmetic, thus increasing the consumer interest, in the product. In some cases, they can also serve to, mask unpleasant odors and color resulting from mixing, and processing the components of the cosmetic. Usually, perfumes and dyes are associated with certain natural, products, i. e., pink with the scent of strawberries or, roses, green with mint, yellow with lemon, blue with, the sea, : : :. Due to the low amount of dye and perfume, added to cosmetics, in many formulations, information, , on their content is not assigned or provided, leaving this, amount to the criteria of the manufacturer., Water, Since ancient times, water has been used for both hygienic and curative purposes. It has been suggested that, cavemen used it for this latter purpose, since they observed that injured animals flocked to warmer springs, and to the sea to relieve their injuries., , 44.6 Major Functions of Some Marine Components, in Cosmetics and Cosmeceuticals, , Part G | 44.6, , In this section, a survey of the major activities provided by marine-derived components with application, in cosmetics and cosmeceuticals is presented. The traditional classification into both additives or ingredients, and active agents was followed. However, recent studies, have evidenced the biological actions of some fractions,, i. e., hydrocolloids or pigments, conventionally used for, thickening or for coloring purposes, respectively, and, they could also provide other beneficial actions., , 44.6.1 Physicochemical, and Technological Properties, Surfactants, Emulsifiers, Thickeners,, Stabilizers, Moisturizers, and Gelling Agents, Surfactants and emulsifiers are amphiphilic compounds containing both hydrophilic and hydrophobic, moieties with many potential applications related to, emulsification foaming, wetting, dispersion, and solubilization of hydrophobic compounds [44.44]. Marine microorganisms have been studied for the production of biosurfactants and bioemulsifiers [44.45],, including protein polysaccharide complexes from, Acinetobacter [44.46], Pseudomonas [44.47], Myroides [44.48], Streptomyces [44.49], Yarrowia [44.50],, Rhodotorula [44.51], and Halomonas [44.52]; glycolipids from Halomonas [44.53], Rhodococcus [44.54],, and Alcanivorax sp. [44.55]; lipopeptides from Bacillus, sp. [44.56, 57] and from the sponge-associated marine actinomycetes Nocardiopsis [44.58, 59]; bile from, Myroides bacterial strains [44.60]; and exopolysaccharides from Bacillus [44.61], Planococcus sp. [44.62],, and Cyanothece sp. [44.63]. Table 44.1 shows some, examples of marine ingredients with cosmetic application and their major technological properties. Marine, lecithins, a mixture of phospholipids comprising pre-, , dominantly long-chain and highly unsaturated fatty, acids esterified on the glycerol backbone, are natural emulsifiers with traditional cosmetic use. Lecithins, show excellent gelation in non-polar solvents when, combined with water [44.64] and serve as an organic, medium to enhance dermal penetration of poorly permeable drugs by effectively partitioning into the skin., Seaweeds are the major source for thickeners, stabilizers, and gelling agents in the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries, the so-called phycocolloids that, include alginate, carrageenan, and agar. Alginates, cellwall polyuronic acids from brown seaweeds, exhibit, gelling properties resulting from their anionic properties and differing ratios of ˇ-D-mannuronic and ˛-Lguluronic acids. They act also as wound healers and as, excipients absorbable by the epidermis. Carrageenans,, isolated from marine red algae, are widely used as, emulsifiers, gelling, stabilizers, or thickeners in toothpastes, lotions, sun ray filterers, shaving creams, shampoos, hair conditioners, and deodorants. In toothpaste,, carrageenan is used as a stabilizer to prevent ingredients from separating. Shampoos and cosmetics creams, contain carrageenans as thickening agent [44.65, 66]., Chitosan is a multifunctional bioactive compound, and is widely used in food, biotechnology, cosmetics,, and medicine. Chitosan, which is soluble in acidic media, is a natural polysaccharide that is obtained from the, polysaccharide chitin [44.67]. Chitin (poly(ˇ-(1 ! 4)N-acetyl-D-glucosamine)) is one of the most abundant, biopolymers in nature after cellulose. Chitins are synthesized by sea animals, such as annelida, mollusca,, previously named coelenterate and crustaceans (lobster,, crab, shrimp, prawn, and krill), microorganisms such as, green algae, yeast (ˇ-type), fungi (cell walls), brown, algae, spores, chytridiaceae, ascomydes, and blastocladiaceae [44.68]. Chitosan can be obtained from shrimp

Page 7 :

Cosmetics from Marine Sources, , 44.6 Major Functions of Some Marine Components in Cosmetics and Cosmeceuticals, , 1021, , Table 44.1 Technological properties of some ingredients from marine sources with cosmetic use, Active component, Source, Surfactants, emulsifiers, thickeners, stabilizers, moisturizers, and gelling agents, Acid- and/or pepsin- Fish species, Illex coindetii (squid), deep-sea redfish, threadfin bream, walleye pollock,, soluble collagen, brownstripe red snapper, or unicorn leatherjacket, Alginates, Brown algae, Bile acids, Myroides, Carrageenans, Red algae, Myroides, Streptomyces, Yarrowia, Rhodotorula, Halomonas, Chitosan and chitin, Sea animals as annelida, mollusca, coelenterata, and crustaceans (lobster, crab, shrimp,, prawn, and krill), microorganisms such as green algae, yeast (ˇ-type), fungi (cell walls),, brown algae, spores, chytridiaceae, ascomydes, and blastocladiaceae, Collagen, Scylla serrata; Chondrosia reniformis; bivalve molluscs; Ircina fusca, Takifugu rubripes skin, Exopolysaccharides, Bacillus, Planococcus, Cyanothece, Gelatin, Fish species (cod, Atlantic salmon, megrim, squid, Nile perch, hake, skate, grass carp,, yellowfin tuna, and channel catfish), Glycolipids, Halomonas, Lipopeptides, Bacillus, Nocardiopsis alba, Cyanobacteria, Porphyridium cruentum, Corallina elongata, Penaeus semisulcatus, , by-products, which are annually produced in high, amounts [44.81]. Chitosan and its derivatives are ingredients in various cosmetics, nail lacquers, toothpaste,, lotions, hand and body creams, and hair care products,, where they are used as emulsifiers, surfactants, gelling,, stabilizers, thickeners, film-former, and also to encapsulate active compounds [44.82]. Chitin-related products,, particularly chitosan and its derivatives, are used in several fields as a new type of functional material, based, on their diverse biological and physicochemical characteristics [44.83]. They promote wound healing and, are suited for cosmetic restoration. The combination, with other active agents has been proposed, i. e., with, taurine, which has effects on cell proliferation, inflammation, and collagen synthesis, and exhibits antioxidant, effects [44.84]. The cosmetic use of chitosan accounts, for 5% in the global market, although at the European, level this application represents 20% [44.83]., Gelatin is a soluble protein compound obtained, by partial hydrolysis of collagen. The most important properties of collagen and gelatin are associated, with their gelling and water binding behavior (gel formation, texturizing and thickening) and their surface, behavior (emulsion formation and stabilization, adhesion and cohesion, and protective colloid function)., , [44.69], [44.65], [44.60], [44.65], [44.48–52], [44.68], , [44.70–74], [44.61–63], [44.75, 76], [44.53], [44.56–58], [44.77], [44.78], [44.79], [44.80], , Traditionally the cosmetic application of gelatin was, based on its gel-forming and viscoelastic properties,, but more recently it has been used as a moisturizer, in cosmetic creams for dry skin and has high potency, in tissue regeneration [44.69]. Collagen from sea animals, such as the marine sponges Ircina fusca [44.74], and Chondrosia reniformis [44.72], sea urchins [44.85],, the marine crab Scylla serrata [44.70], or bivalve molluscs [44.73] is a safer alternative to those of terrestrial, origin [44.71, 72]. The number of fish or marine species, studied for gelatin extraction is continually growing due, to the interest in valorization of by-products from the, fish industry [44.69, 75, 76]., Moisturizers have beneficial effects in treating dry, skin. Orange roughy (Hoplostethus atlanticus) oil,, a marine-derived wax ester, performed comparably, to a petrolatum-based moisturizer (vaseline) in clinical trials in subjects with moderate to severe skin, dryness [44.86]., Colorants, A wide variety of pigments, like chlorophylls,, carotenoids, and phycobiliproteins, which exhibit colors ranging from green, yellow, and brown to red are, present in algae and in other marine organisms., , Part G | 44.6, , Colorants, Phycocyanin, ˇ-phycoerythrin, R-phycoerythrin, Astaxanthin, , References

Page 8 :

1022, , Part G, , Application of Marine Biotechnology, , Part G | 44.6, , The carotenoid pigments have significant application in the cosmetic industry, especially astaxanthin,, which is found in salmon, rainbow trout, sea bream,, lobster and caviar, crustaceans, the marine bacterium, Agrobacterium aurantiacum, and the green microalga, Haematococcus pluvialis [44.80]., Phycobiliproteins, including phycoerythrin, phycocyanin, allophycocyanin, and phycoerythrocyanin, are, a group of colored proteins commonly present in, cyanobacteria (blue–green algae), in a class of biflagellate unicellular eukaryotic algae (cryptomonads), and, in Rhodophyta (red algae). They are used in the cosmetic industry to replace synthetic dyes that may be, toxic, carcinogenic, or otherwise unsafe [44.87, 88]. In, Japan, where algal cultivation is a well-developed industry, some natural pigments from phycobiliproteins, were have patented early [44.89]. ˇ-phycoerythrin is, the most valuable of the phycobiliproteins due to its intense and unique pink color [44.90], heat stability, and, pH tolerant characteristics, and has been applied as natural pink and purple colorants for lipsticks, eyeliners,, and also formulations for cosmetic products [44.91]., Phycocyanin, a blue pigment, is also used as a colorant, in eyeliners [44.77]., Carotenoids are isoprenoid molecules synthesized, de novo by photosynthetic plants, fungi, and algae., Carotenoids are lipophilic compounds, some of which, act as provitamin A. These compounds are classified, into two major groups based on their structural elements; carotenes, constituted by carbon and hydrogen, (e.g., ˇ-carotene, ˛-carotene and lycopene), and xanthophylls, constituted by carbon, hydrogen, and additionally oxygen (for example, lutein, ˇ-cryptoxanthin,, zeaxanthin, astaxanthin, and fucoxanthin). Industrially,, these carotenoids are used as pigments in food, feed,, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. They can be produced, by chemical synthesis, fermentation, or isolation from, natural sources; most commercially used carotenoids, (for example, ˇ-carotene, astaxanthin, and canthaxanthin) are obtained by chemical synthesis [44.92]., Many macroalgae and microalgae are rich in, carotenoids, which aid in the absorption of sunlight. Compared to other sources, the production of, carotenoids from algae has many advantages, including lower costs, easy and environmentally friendly, extraction, and the possibility of supplying materials without limitations or seasonal variations [44.93]., Recently, there has been considerable interest in, carotenoids associated to their antioxidant properties [44.94–96] and because of their antiobesity and, anabolic effects [44.97–99]., , Antioxidants, The antioxidant activity of many marine-derived substances has been studied extensively [44.100–102]. The, interesting aspect of this property is not only in relation to the increase in shelf life of the products, by, delaying or avoiding the oxidation of fats and oils,, but also due to other biological actions. The imbalance between generation of the reactive oxygen species, (ROS) and the scavenging or detoxification by the organisms causes oxidative stress, which could lead to, disruptions in normal mechanisms of cellular signaling and be involved in the development of aging and, chronic diseases. Different marine-derived compounds, have been confirmed as potent antioxidants, including, oligosaccharides, peptides, phlorotannins, carotenoids,, and vitamins. Table 44.2 shows some examples of, the major components obtained from marine sources,, which could be responsible for antioxidant properties., Due to the extensive and growing number of publications, only review papers are mentioned to illustrate the, potential of some fractions from macroalgae. In most, studies crude extracts and fractions are evaluated, and, the presence of a mixture of compounds can provide, a more potent antioxidant action because of the synergistic interaction between them [44.100]., Mixtures of different compounds have also been, proposed; one example is the combination of isolated, and purified marine oligosaccharides with collagen peptides derived from tilapia fish skin. This preparation, showed a higher radical scavenging activity than the individual components [44.103]., Algae are one of the most studied sources of, marine antioxidants. Extracts from brown algae have, been observed to be more effective than those from, red and green algae in terms of antioxidant activity [44.102, 122]. One of the suggested reasons for, this is the phlorotannin content, and the characterization of some phloroglucinol derivatives has been published [44.123–126]. However, other components, from, the polysaccharide and carotenoid fraction [44.96],, are efficient antioxidants and could contribute to this, activity. Aqueous and solvent extracts are the most, used, but alternative processes have been proposed,, i. e., fermentation of the Ecklonia cava processing byproduct [44.127]. Other relevant sources include the, microalgae to produce carotenoids, the fish protein fraction to obtain peptides [44.94, 128, 129], and fish roe, as a source of gadusol [44.130]. Less explored organisms have been studied, i. e., the marine phanerogam, Syringodium filiforme, growing associated to Thalassia, testudinum [44.131] or less conventional agents, such as

Page 9 :

Cosmetics from Marine Sources, , 44.6 Major Functions of Some Marine Components in Cosmetics and Cosmeceuticals, , 1023, , Table 44.2 Major families of compounds from marine sources showing in vitro antioxidant activity, , Component, Carotenoids and, other terpenoids, , Peptides, , Phlorotannins, , Low molecular, weight fractions from algal, polysaccharides, , Enzymatic hydrolysis, of protein from fish, by-products: skin,, head, viscera, trimmings, liver, frames,, bones, and roes, Extracts from brown, algae, , Macroalgae and, seagrasses; tropical,, temperate, and, polar fish, Aqueous extracts, and fractions from, seaweed further subjected to chemical, and/or enzymatic hydrolysis, , Antioxidant activity, Radical scavenging: DPPH, 12-DS, NB-L, AAPH, ABTS,, ABAP, superoxide anion, TRAP Cu�Zn SOD and activity, catalase activity in rat plasma and erythrocytes, Protection against oxidation, Reducing activity, scavenging activity against DPPH radical,, ABTS radical superoxide anion, hydroxyl radical, hydrogen, peroxide, lipid peroxidation inhibition activity, ferrous and, cuprous ion chelating activity, prevention of oxidation in, emulsion of ˇ-carotene linoleic acid and in lecithin, liposomes, Scavenging activity against DPPH radical, hydroxyl radical, and superoxide anions, protection against oxidation, ferrous, and cuprous ion chelating activity, reducing activity, protection against oxidative stress in cells, protection of membrane, oxidation in cells, Scavenging activity against DPPH radical, reducing power,, endogenous enzyme activity of superoxide dismutase and, glutathione peroxidase, Scavenging activity against DPPH radical, hydroxyl radical, and superoxide anions. Inhibition of H2 O2 induced hemolysis of rat erythrocytes, protection on lipid peroxidation of, liver homogenate, prevention of oxidation in emulsion of, ˇ-carotene linoleic acid, in phosphatidylcholine liposomal, suspension, restoration of endogenous antioxidant enzymes:, superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase; ferrous, ion chelating activity, , References, , [44.95,, 104–106], [44.107–, 110], , [44.102,, 105, 111–, 113], , [44.12, 114,, 115], , [44.105,, 116–121], , DPPH: 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; ABAP: 2,20 -azo-bis-2-amidinopropane; ABTS: 20 azinobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid); SOD: superoxide dismutase; TRAP: total radical antioxidant parameter; AAPH: 2,20 -azobis(2amidino-propane) dihydrochloride; 12-DS: 12-doxylstearic acid; NB-L: nitrobenzene with linoleic acid, 5-hydroxymethyl- 2-furfural isolated from the red algae, Laurencia undulata [44.132]., , 44.6.2 Biological Activities, Photoprotective and Anti-Photoaging, Skin is the largest part exposed in the human body,, and it is well established that overexposure to UV, radiation provokes acute sunburn reaction. Sun overexposure is clinically manifested as erythema, and, chronically irradiated skin is associated with abnormal cutaneous reactions such as epidermal hyperplasia,, accelerated breakdown of collagen, and inflammatory, responses [44.133]. The use of photoprotective agents, , mainly determines the delay of the effects of photoaging by decreasing the adverse effects of free radicals., The increased public awareness towards the importance, of skin care has fostered the study and the demand of, compounds or extracts aimed at reducing the effects of, UV irradiation as preventive or palliative agents. Recent, studies have focused on marine organisms as a source, of natural bioactive molecules and some UV-absorbing, algal compounds are under investigation as candidates, for new natural sunscreens, photoprotective, and antiphotoaging agents [44.134, 135]. Mycosporines and, mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs), which are accumulated by a wide range of microorganisms, prokaryotic (cyanobacteria), as well as eukaryotic (microalgae,, , Part G | 44.6, , Vitamin C and E, , Source, Microalgae,, macroalgae marine, sponges

Page 10 :

1024, , Part G, , Application of Marine Biotechnology, , yeasts, and fungi), and a variety of marine macroalgae,, corals, and other marine life forms, can be used as sunscreen compounds [44.136–138]., Solvent extracts from algae [44.135, 139, 140] and, from other organisms, such as fungi, lichens, bacteria, cyanobacteria, and marine animals [44.141, 142], have been explored as a source of novel photoprotective compounds for the formulation of pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical products. Several pure algal compounds have shown this activity, for example, sargaquinoic acid and sargachromenol from Sargassum sagamianum [44.143], dieckol from Ecklonia, cava [44.133], or fucoxanthin from Sargassum siliquastrum [44.144]. Bacterial exopolysaccharides, i. e., from, the bacterium Alteromonas macleodii, have also been, proposed to alleviate ultraviolet B radiation (UVB), aggression [44.145]., , Part G | 44.6, , Anti-Wrinkling and Skin Regeneration, Skin aging involves changes in skin physical properties, and visible signs on the surface due to the degradation, of the extracellular matrix in both the epidermal and, dermal layers, producing visible signs such as irregular, dryness and pigmentation, sallowness, telangiectases,, premalignant lesions, laxity, and wrinkling. Some antiaging cosmetics are designed to treat premature aging, caused by environmental factors [44.146]. The skin, regeneration properties of some red algae, such as Porphyra atropurpurea and Chondrus crispus, have been, used traditionally to treat wounds and burns [44.147]., The methanol extracts of the alga Corallina pilulifera, reduced the expression of human matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2 and -9 induced by UV irradiation in, fibroblasts [44.148]. Joe et al. [44.149] demonstrated, the inhibitory effect of eckol and dieckol from Ecklonia species on MMP-1 expression in human dermal, fibroblasts and suggested their use for the prevention, and treatment of skin aging., Depigmenting or Whitening, Tyrosinase, also referred to as polyphenol oxidase, is, a metalloenzyme oxidase that catalyzes two distinct, reactions of melanin synthesis in which l-tyrosine is hydroxylated to L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine L-DOPA, (monophenolase activity). The latter is subsequently, oxidized to dopaquinone (diphenolase activity). Tyrosinase is the rate-limiting enzyme in melanin production,, which occurs in melanocytes that are located within, the basal epidermis [44.150]. Melanin has a photoprotective function in human skin, but its abnormal, accumulation can result in hyperpigmentation with un-, , desirable esthetic implications [44.151]. The downregulation of tyrosinase is an efficient method for the, inhibition of melanogenesis, addressed by a number, of approaches, including the direct inhibition of tyrosinase, the acceleration of tyrosinase degradation, the, inhibition of tyrosinase mRNA (messenger ribonucleic, acid) transcription, aberration of tyrosinase glycosylation or interference with melanosome maturation and, transfer [44.151]. Accordingly, a huge number of compounds acting by alternative approaches have been, identified successfully. The number of studies searching for potent melanogenesis inhibitors from natural, sources for cosmetic uses is increasing, as there is a demand for tyrosinase inhibitors in the cosmetic industry, due to their skin-whitening effect [44.152]., In a screening of 43 marine algae for antibrowning, effects, Endarachne binghamiae, Schizymenia dubyi,, Ecklonia cava, and Sargassum siliquastrum inhibited, cellular melanin synthesis and tyrosinase activity similarly to kojic acid. Furthermore, whereas toxicity was, observed in the positive controls, no toxicity was observed in the algal species [44.153]. Kojic acid was, identified as the active compound isolated from the acetone extracts produced from selected strains in a screening study with 600 organisms of marine fungi [44.154]., Phlorotannins from marine brown algae are effective tyrosinase inhibitors and are potential ingredients, for treating dermatological disorders associated with, melanin [44.155]. Phloroglucinol, eckol, and dieckol, from Ecklonia cava showed effects on melanogenesis, via the inhibitory effect on tyrosinase and reduction of, melanin synthesis, among them, dieckol showed higher, activity than kojic acid [44.133] and also showed more, effective melanin reducing activities than arbutin in, B16F10 melanoma cells, without apparent cytotoxicity [44.156]. 7-phloroeckol from Ecklonia cava inhibited melanin production in melanoma cells more potently than arbutin and kojic acid [44.157]. In increasing, order phlorofucofuroeckol A, eckstolonol, phloroglucinol, eckol, and dieckol from Ecklonia stolonifera, inhibited tyrosinase [44.158]. Also diphlorethohydroxycarmalol demonstrated protective effects on melanogenesis [44.126]. Solvent extracts from bacteria of the, Pseudomonas genus, associated with marine invertebrates, were found to be effective whitening agents in, assays with cultured melanocytes, cultured skin, and, in vivo zebrafish [44.156]. Other antimelanogenic compounds are fucoxanthin [44.144, 159], and geoditin A,, an isomalabaricane triterpene isolated from the marine, sponge Geodia japonica, with potent activity and relatively low cytotoxicity [44.160].

Page 11 :

Cosmetics from Marine Sources, , 44.6 Major Functions of Some Marine Components in Cosmetics and Cosmeceuticals, , and in vivo antitumor properties [44.174]. Synthetic, derivatives of marine natural products have also been, proposed, i. e., sarcodiol, a derivative of sarcophine that, inhibits melanoma cell proliferation [44.175]., Anti-Pruritic, Anti-Inflammatory Activity,, and Antiallergic Activity, Inflammatory skin diseases such as contact dermatitis,, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis are skin disorders that, constitute a major health problem worldwide. One of, the most challenging pruritic skin inflammatory diseases needing a better therapeutic approach is atopic, dermatitis. This skin inflammatory disease can occur, at any age and is characterized exclusively by the, elevated serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels and peripheral eosinophilia. Inhibition of IgE production or, reduction in the concentration of IgE would be the optimal therapeutic approach in treating inflammatory skin, diseases [44.176]., Allergic diseases are caused by chemical or immunological activation of mast cells leading to a massive release of endogenous mediators, such as histamine, as well as a wide variety of other inflammatory mediators, such as eicosanoids, proteoglycans,, proteases, and several proinflammatory and chemotactic cytokines. Among the inflammatory substances, released from the effector cells, histamine remains the, best characterized and most potent vasoactive mediator, implicated in the acute phase of immediate hypersensitivity. An allergic reaction that produces mild to, moderate symptoms can be easily treated with antihistamine compounds [44.177]., Many natural compounds from natural marine, organisms exhibit antiallergic and anti-inflammatory properties and hyaluronidase inhibitory activities [44.178]. Hyaluronidase is an enzyme that depolymerizes the polysaccharide hyaluronic acid in the skin, and is known to be involved in allergic effects, migration of cancers, and inflammation. Mainly marine algae, have received much attention because they are a valuable source of chemically diverse bioactive compounds, with numerous health benefits in the treatment of allergic disorders [44.177]., The levels of serum IgE and histamine were suppressed in rats fed a diet supplemented with a dried, Eisenia arborea extract [44.179, 180]. Phlorotannins are the most studied group of compounds, that have shown potential pharmacological applications as antipruritic, anti-inflammatory, and antiallergic agents [44.112, 155]. Several phlorotannins exhibit potential antiallergic action on human and rats, , Part G | 44.6, , Human Skin Melanoma, Cutaneous melanoma is one of the most aggressive, forms of skin cancer with high metastatic potential, and strong resistance to radiation, immunotherapy, and, chemotherapy [44.161]. The incidence of melanoma, is rising at an alarming rate, possibly associated with, the increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation, and, has become a major public health concern in many, countries [44.162]., The carotenoid fucoxanthin has antiproliferative effects in vitro and in vivo on melanoma B16F10 cells, by inducing apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest [44.163]., A low molecular weight fraction of the water-soluble extract of Porphyra yezoensis inhibited proliferation of mouse B16 melanoma cells [44.164]. Several, polysaccharide fractions, especially those from brown, marine alga (Ecklonia cava, Sargassum stenophyllum,, S. hornery, Costaria costata) decreased melanoma cell, tumor growth [44.165–167]. Marine peptides and depsipeptides have shown antimelanoma activity. Among, them aplidine, a cyclodepsipeptide isolated from the, tunicate Aplidium albicans, and kahalalide F, a depsipeptide isolated from the herbivorous marine mollusk, Elysia rufescens, E. ornata, or E. grandifolia has undergone phase III clinical study in patients with advanced, malignant melanoma [44.129, 168]., Jaspine B, an anhydrophytosphingosine derivative isolated from the marine sponge Jaspis sp., decreases the viability of murine B16 and human SKMEL-28 melanoma cells in a dose-dependent manner., Jaspine B is able to kill melanoma cells by acting, on sphingomyelin synthase, an enzyme that converts, de novo ceramide into the membrane lipid sphingomyelin, and may represent a new class of cytotoxic compounds [44.169]. Exposure of SK-MEL-2, cells to dideoxypetrosynol A, a polyacetylene from, the sponge Petrosia sp., resulted in growth inhibition and induction of apoptosis in a dose-dependent, manner [44.170]. Marinomycin A from a marine actinomycete of the genus Marinispora showed remarkable, selectivity for melanoma cell lines in the US National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) 60-cell panel [44.171]., A biindole, halichrome A, from the marine sponge, Halichondria okadai, exhibited cytotoxicity against, melanoma cells [44.172]. Also unusual polyunsaturated, fatty acids (PUFAs), such as several !3 fatty acids, and the !7 heneicosa-5,8,11,14-tetraenoic acid (21 W 4, n-7) from the marine opisthobranch Scaphander lignarius, were active against human cancer cell lines, of melanoma [44.173]. Elatol, a sesquiterpene isolated, from algae Laurencia microcladia, showed in vitro, , 1025

Page 12 :

1026, , Part G, , Application of Marine Biotechnology, , Part G | 44.6, , basophilic leukemia cultured cell lines, 6,60 -bieckol,, 1-(30 ,50 -dihydroxyphenoxy)-7 (200 ,400 ,6-trihydroxyphenoxy)-2,4,9-trihydroxydibenzo-1,4-dioxin, and dieckol, suppressed binding activity between immunoglobulin, E (IgE) and high-affinity receptor for the Fc region, of immunoglobulin E (Fc"RI ) receptors [44.181],, and fucodiphloroethol and phlorofucofuroeckol A reduced histamine release [44.182, 183]. Phlorotannins, such as eckol, phlorofucofuroeckol A, dieckol, and, 8,80 -bieckol isolated from Eisenia bicyclis and Ecklonia, kurome have shown a stronger inhibition effect against, hyaluronidase than well-known inhibitors such as catechin and sodium cromoglycate [44.184]. From these, results, it is understood that phlorotannins can be useful in the management of allergic and inflammatory, skin diseases through the reduction of IgE concentration and their histamine inhibitory activities. The, carotenoid fucoxanthin was found to exhibit anti-inflammatory effects [44.185]., The polysaccharidic fractions of marine algae have, promising anti-inflammatory activities [44.186]., Alginic acid exhibited an inhibitory effect on, hyaluronidase and on histamine release from mast cells, [44.187], suppressed antigen-induced Th2 development, by inducing interleukin IL-12 production, and inhibited, in vivo IgE production, suggesting its potential as, an antiallergic agent [44.188]. Fucoidan significantly, reduced IgE production in human peripheral blood, mononuclear cells of patients and healthy donors,, even after the onset of atopic dermatitis [44.189]. Oral, administration of porphyran, a major component of the, red algae Porphyra tenera and P. yezoensis, suppressed, the contact hypersensitivity reaction (ear edema), induced by 2,4,6-trinitrochlorobenzene [44.190]., Epicutaneous application of sacran, a sulfated polysaccharide extracted from the alga Aphanothece sacrum,, inhibited the development of allergic dermatitis skin, lesions in mice [44.191]., PUFAs are metabolized by skin epidermal enzymes, into anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative metabolites, that are associated with a variety of benefits regarding inflammatory skin disorders [44.192, 193]. PUFAs, can be recovered from marine protists and microalgae [44.194], Antarctic krill [44.195], marine and fish, products, and by-products [44.196, 197]. Among the, fatty acids, the ¨3-PUFA, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA,, 20 W 5n-3), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22 W 6n-3),, possess potent immunomodulatory activities [44.198], and can reduce the sensitivity of human skin to sunburn [44.199]. Animal experiments and clinical intervention studies indicate that diseases such as lupus, , erythematosis and psoriasis, characterized by a high, level of IL-1 and the proinflammatory leukotriene LTB4, produced by ¨-6 fatty acids, can be treated with ¨-3, fish oil [44.198]. In this context, marinosomes, i. e., liposomes made of a natural marine lipid extract, were, envisaged for the prevention and treatment of skin, diseases [44.200]., Antimicrobial Activity, Bacterial skin infections are very common and can, range from being merely annoying to deadly. Most bacterial infections of the skin are caused by two bacteria,, Staphylococcus aureus and a form of Streptococcus. Viral infections of the skin are common and include warts,, cold sores, chicken pox, shingles, molluscum contagiosum; and hand, foot, and mouth disease. The three main, types of viruses that cause most viral skin infections are, the human papilloma virus, the herpes simplex virus, type 1 (HSV-1, HSV-2) and the pox virus. Whereas, these viruses cannot be cured, their effects on the skin, can be prevented or minimized through proper medical, treatment. Examples of compounds from marine origin, showing antimicrobial and antiviral action are listed in, Table 44.3. This activity is also interesting with respect, to the protection of cosmetic products from microbial, contamination, thus having the role of preservatives., A number of studies has been performed concerning, the antimicrobial activity of phenolic compounds isolated from marine sponges. 2-(20 ,40 -dibromophenoxy)4,6-dibromophenol from the marine sponge Dysidea, granulosa exhibited potent and broad spectrum in, vitro antibacterial activity, especially against methicillin-resistant and sensitive Staphylococcus aureus,, vancomycin-resistant and -sensitive Enterococci, and, Bacillus sp. [44.198]. Marinomycin A from a marine actinomycete of the genus Marinispora [44.171], and dehydroxychlorofusarielin B, a diterpene from, the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus sp., exhibited, antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, and methicillin-resistant S. aureus [44.207]. Parabens,, widely used in cosmetics, can be biosynthesized by, a marine bacterial strain belonging to the genus Microbulbifer [44.216]. To illustrate the potential of algae, examples related to recent studies are summarized, either evaluated as extracts [44.217] or as pure, compounds and fractions. Phlorotannins (phloroglucinol, eckol, fucofuroeckol-A, phlorofucofuroeckol-A,, dioxinodehydroeckol, 8,80 -bieckol, 7-phloroeckol, and, dieckol; and triphloroethol A, 6,60 -bieckol and 8,4000 dieckol) from brown algae were active against Campylobacter jejuni, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia,

Page 15 :

Cosmetics from Marine Sources, , 44.7 Treatments Based on Marine Resources, , 1029, , 44.7 Treatments Based on Marine Resources, functional agents responsible for those effects. Acidic, cosmetic water isolated from seawater decreased tyrosinase and melanin activities in human epidermal, melanocytes (HEMn-MP) and presented anti-growth, and antimigration effects on human skin melanoma, cells (A375.S2) [44.235]., In contrast to other cosmetic ingredients, the benefits of topically appliedingredients, the benefits of, topically applied mineral salts have been largely ignored and unexploited. The most famous example for, balneotherapy is the Dead Sea minerals, reported to be, safe and effective for dermatological disorders in both, in vitro and in vivo studies [44.227, 236–238]. Magnesium, sulfur, sodium, bromine, and iodine are known, for their healing properties for psoriasis sufferers and, patients with rheumatic complaints, and appear to be, the prominent actors in rheumatology and dermatology, when incorporated in cream or mud [44.239]. Because, of its effect in retention of water in the skin, regulation, of the pH of the skin, acne repair and prevention, enhancing of blood circulation, and antiaging effect, sea, mud has been added to cosmetic formulae, cosmetics,, and therapeutic treatments [44.240]., Heated seawater baths have been recommended, to stimulate a dilatation of cutaneous vessels. Baths, at temperatures below 27 ı C and between 28 ı C and, 32 ı C can stimulate the individual and increase the, amount of blood evacuated from the heart to the large, vessels, decongest and smoothen articulation, and have, been prescribed for the treatment of chronic evolutive polyarthritis. Showers prior to and after baths, exert a dual thermal and mechanical action on vessels and nerve endings; alternation of short cold and, warm water sprays may have the same tonifying ef-, , Table 44.4 Chemical composition (g kg�1 ) of seawater [44.228, 231–234], Seawater chemical composition, Cations, (g kg�1 ), Na2C, NaC, Mg2C, Ca2C, KC, Sr2C, Fe2C, , 10.35, 0:35�10:98, 0:56�1:37, 0:36�1:98, 0:36�0:4042, < 0:0024�0:0080, 0:01�0:057, , Anions, , (g kg�1 ), , Cl�, SO2�, 4, HCO�, 3, Br�, CO2�, 3, B.OH/�, 4, F�, OH�, , 14:72�19:60, 2:67�2:79, 0:1061�0:15, 0:05�0:0681, 0:0145�0:02, 0.0080, 0:0012�0:0013, 0.0001, , Neutral compounds, B.OH/3, CO2, , (g kg�1 ), 0.0197, 0.0004, , Part G | 44.7, , Marine resources have traditionally been the basis of, effective and safe therapies associated with well-being., Some aspects of thalassotherapy and, particularly, of algotherapy are discussed here., The term thalassotherapy, from the Greek word for, sea (thalasso), refers to the therapeutic use of seawater,, sea products, and shore climate for their beneficial effects on the skin [44.226]. Standard procedures include, hot seawater baths, underwater massage, jet showers, and algal and peloid therapy. Thalassotherapy is, used as an alternative treatment for medical conditions, and has become a popular tourist attraction for relaxation and stress reduction, and spa therapy is offered, claiming prevention and treatment of dermatological, diseases [44.227]., The term peloid, which was first defined in, 1949 by the International Society of Medical Hydrology, during its 6th Conference held in Dax, (France), refers to the therapeutic use in mask, cataplasm, or bath forms of naturally occurring clays, and minerals mixed with organic matter after physical,, chemical, biological, and geological modifications or, maturation [44.228–230]., In thalassotherapy, trace elements found in seawater, such as magnesium, potassium, calcium, sodium,, and iodine are believed to be absorbed through the, skin. The marine water composition, with variable, salinity content (usually 3:5%) is made up by the elements shown in Table 44.4 [44.231]. Filtered and, processed by reverse osmosis membrane and electrodialysis seawater has shown antibacterial action, antiinflammation potential, and superoxide anion radical, scavenging capacity. It was proposed that magnesium,, zinc, potassium, and calcium ions could be the bio-

Page 16 :

1030, , Part G, , Application of Marine Biotechnology, , Part G | 44.7, , fect as the Finnish sauna [44.66]. There are another, treatments as such as ammotherapy or psammotherapy (partial or full-body warm sand baths), methodical, exposure to the sun (heliotherapy), and marine climatotherapy (atmosphere, temperature, humidity, wind,, barometric pressure, etc.) with beneficial effects to skin, health [44.241]., Among the variety of marine resources available,, algal extracts are being extensively demanded and, used. Phytotherapy, and its component algotherapy,, were officially recognized in 1986 by the French Ministry of Health as a reimbursable medical service by, the National Health Scheme. However, this recognition is not found in other countries, and some of the, claimed beneficial effects of these therapies have not, been sufficiently contrasted with scientific and medical, evidences., Some examples of traditional algal treatments, should be mentioned. Lithothamnium calcareum is, a marine alga whose thallium is used in the treatment, of decalcification, osteoporosis, painful joints, chronic, fatigue, rheumatism, gingivitis, and stomach pains. A, rather wide range of marine algae enter in the packs, used in thalassotherapy, and algal flours or algal salts, are sold for use in home bath therapy. Poultices of Fucus, Laminaria, Ulva, and Ascophyllum (with or without Lithothamnium powder) are heated to 40�50 ı C, and applied at thalassotherapy clinics to limbs to relieve rheumatism and arthritis pains. Other algae, such, as the red Porphyra and Eucheuma, and the brown, Laminaria and Undaria are frequently employed in, algotherapy [44.66]., Cosmetic treatments with algae have stimulating, and regenerating properties, associated with minerals,, vitamins, and amino acids [44.242]. Other reported, actions include tonifying, antiseborrheic, conditioning, moisturizing, bacteriostatic, UV-radiation blocking, and antioxidant [44.243–245]. Table 44.5 summarizes some studies confirming these actions. Seaweeds, are particularly effective in slimming, firming, anticellulite, and the treatment of hair disorders and diseases., , 44.7.1 Firming, These extracts are intended to restore the elasticity of, the skin, contributing to its rejuvenation. They improve, intercellular exchanges and also facilitate and potentiate, the action of other drugs. Brown algal sulfated polysaccharide fucoidan is helpful in the maintenance of the, skin’s elasticity by increasing hydration and, thereby,, improving the skin’s elasticity [44.254]., , Seaweed extracts, rich in oligo-elements, vitamins,, marine plankton, amino acids, and other components, are sold as potent lipolytic reducers. This action has, been ascribed to the ability of releasing heat energy,, increasing the metabolism of fat cells (adipocytes), and triggering combustion of triglycerides [44.66]., Fucoxanthin, which is characteristic of brown algae, has unique mechanisms of antiobesity properties [44.8]. The potential effect of the seaweed algae on weight reduction is associated with well-being, sleep amelioration, and an improvement of skin, tonicity [44.255]., , 44.7.2 Cellulite, Cellulite is characterized by alterations on the skin surface of the buttocks and posterior and lateral thighs,, and mainly affects women. Its pathogenesis is not completely understood, but it could be due to structural,, inflammatory, morphological, and biochemical alterations of the subcutaneous tissue. Topical treatments, for cellulite include activities related to increased microcirculation flow, reduced lipogenesis and promoted, lipolysis, restoration of dermal and subcutaneous tissue,, and free radical scavenging [44.256]., Table 44.5 Some studies about cosmetic treatments with, , algae, Active component, Source, Adipolysis and skin appearance enhancer, Fucoxanthin, Brown algae, Undaria pinnatifida, Sulfated polyFucus vesiculosus, saccharide: fucoidan, Aqueous extract, Fucus vesiculosus,, F. lumbricalis, Hydroglyceric extract Laminaria digitata, Hydroglycolic extract Pelvetia canaliculata, Oily extract rich in, Gelidium cartilagineum, rhodysterol, Sea-salt, Seawater, Prevention of hair disorders, Dieckol, Ecklonia cava, Fucus vesiculosus, DiguanosineArtemia salina, tetra-phosphate, Extract, Grateloupia elliptica, Burn shell, Paracentrotus lividus, Ethanolic extract, Euchema cottonii, Shell, ink, Sepia officinalis, , Reference, [44.246], [44.8], [44.247], [44.248], [44.249], [44.249], [44.249], [44.249], [44.250], [44.66], [44.251], [44.252], [44.251], [44.253], [44.251]

Page 18 :

1032, , Part G, , Application of Marine Biotechnology, , Table 44.6 (continued), Products and action, Antiwrinkle, antiaging, and lifting products, Arthrospira and Spirulina platensis extracts, Polysaccharide from Nannochloropsis oculata, Extract and procollagen peptides from Chlorella vulgaris, Mannitol and extract from Laminaria digitata, Calliblepharis ciliata, Delesseria sanguinea, and Dilsea carnosa extracts, Fucoidan from Undaria pinnatifida, Phormidium persicinum extract, Exopolysaccharides produced by plankton, Fatty acids, vitamins, proteins, peptides, minerals, and free amino acids from salmon roe, Thalassiosira sp., Codium sp., Ulva sp., Hydrating agents, Chondrus sp., Asparagopsis sp., Ceramium rubrum extract, Sea urchin, , Part G | 44.9, , Thalasso and algotherapy, Fucus sp., Laminaria sp., , 44.7.3 Hair Growth Disorders, The demand for products that alter hair growth is, a billionaire’s market, but few natural effective products are available. Ethanol and aqueous extracts from, , Eucheuma cottonii enhances hair growth by higher, proliferative activity [44.253]. The beneficial effect, of Ecklonia cava extracts on the promotion of hair, growth of immortalized vibrissa dermal papilla cells, was reported [44.250]., , 44.8 Products Based on Marine Resources, Currently, a diversity of products based on marinederived ingredients are marketed for different purposes, including: antiaging, whitening, moisturizers,, UV-blocking, and skin or hair specific treatments., These formulations are sold as creams, gels, and lotions, depending on their penetration ability and efficiency and acceptance by consumers. Cosmetic companies are increasingly interested in the development, of novel products with marine-based bioactives. Table 44.6 summarizes some representative actions and, the active marine-derived ingredients that are found in, some commercial formulae. Most of them are crude or, refined extracts, but also purified fractions and compounds are used. Aqueous, solvent, and lipid extracts, are available. Marine lipid extracts contain a large, amount of PUFAs, such as (EPA, 20 : 5n-3) and (DHA,, , 22 : 6n-3), associated with a variety of benefits in, skin disorders treatment. Their encapsulation in liposomes, good vehicles for cosmetic applications, has, proved their suitability to improve storage stability of, bioactives [44.200]., Some components are recognized ingredients with, skin protecting and conditioning actions, or also provide some technological properties, such a viscosity controlling effect, a coloring effect, etc. On the, other hand, some components traditionally used for, conferring technological properties can be of interest as active agents. Furthermore, some compound, used externally may also be effective when proposed, for oral use, as nutraceuticals, fitting into the recent trend to provide beauty from within [44.254, 257,, 258].

Page 19 :

Cosmetics from Marine Sources, , References, , 1033, , 44.9 Conclusions, A great research effort related to the chemical structures, and physical and biological properties of marine natural products has emerged in recent years due, to the fact that these resources are still largely unexplored and may have potential for further development of food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical products. A variety of marine sources have been considered: microorganisms, fungi, macro and microalgae, and by-products from the food industry, such as, fish skin, crustacean skeletons, or cartilages. Seawater and minerals are also sources of effective products. A continuous growth in the market of cosmetic, products formulated with marine bioactive substances, is expected. Both traditional treatments and innovative formulations with novel marine-derived com-, , ponents coexist in commercial skin and hair care, products., The research on bioactive compounds, particularly, those that are found exclusively in marine media, is, highly attractive due to the unique structures, which are, not found in terrestrial sources, and their potent properties. In the next years, the research and development, effort should be focused on the identification of the active metabolites, their detailed mechanisms of action,, the design of clean extraction and purification technologies, and the development of efficient vehicles and, products with enhanced activity, safety, and prolonged, shelf-life. To succeed in this area with impressive potential, a close collaboration of different scientific and, technical disciplines is encouraged., , 44.1, , 44.2, , 44.3, 44.4, , 44.5, , 44.6, , 44.7, , 44.8, , 44.9, , 44.10, , M.T. Alcalde-Pérez: Activos cosméticos de origen, marino: Algas, macromoléculas y otros componentes, OFFARM 23, 100–104 (2004), M.T. Alcalde-Pérez: Cosmética natural y ecológica: Regulación y clasificación, OFFARM 27, 96–104, (2008), A. Kijjoa, P. Sawangwong: Drugs and cosmetics, from the sea, Mar. Drugs 2, 73–82 (2004), S. Saraf, C. Kaur: Phytoconstituents as photoprotective novel cosmetic formulations, Pharmacogn. Rev. 4, 1–11 (2010), D.J. De Vries, P.M. Beart: Fishing for drugs from, the sea: Status and strategies, Trends Pharmacol., Sci. 16, 275–279 (1995), A. Aneiros, A. Garateix: Bioactive peptides from, marine sources: Pharmacological properties and, isolation procedures, J. Chromatogr. B 803, 41–53, (2004), D. Leary, M. Vierros, G. Hamon, S. Arico, C. Monagle: Marine genetic resources: A review of scientific and commercial interest, Mar. Policy 33,, 183–194 (2009), J. Querellou, T. Børresen, C. Boyen, A. Dobson,, M. Höfle, A. Ianora, M. Jaspars, A. Kijjoa, J. Olafsen, G. Rigos, R. Wijffels: A new vision and strategy for Europe (Marine Board-ESF Position Paper),, Mar. Biotechnol. 15, 50–52 (2010), J.F. Imhoff, A. Labes, J. Wiese: Bio-mining the, microbial treasures of the ocean: New natural, products, Biotechnol. Adv. 29, 468–482 (2011), P. Spolaore, C. Joannis-Cassan, E. Duran, A. Isambert: Commercial applications of microalgae,, J. Biosci. Bioeng. 101, 87–96 (2006), , 44.11, , 44.12, , 44.13, , 44.14, , 44.15, , 44.16, , 44.17, , 44.18, , 44.19, , J.H. Fitton, M. Irhimeh, N. Falk: Macroalgal fucoidan extracts: A new oportunity for marine, cosmetics, Cosmet. Toilet. 122, 55–64 (2007), S.K. Kim, Y.D. Ravichandran, S.B. Khan, Y.T. Kim:, Prospective of the cosmeceuticals derived from, marine organisms, Biotechnol. Bioprocess E 13,, 511–523 (2008), F.S. Brandt, A. Cazzaniga, M. Hann: Cosmeceuticals: Current trends and market analysis, Sem., Cutan. Med. Surg. 30, 141–143 (2011), S.R. Milstein, J.E. Bailey, A.R. Halper: Definition, of cosmetics. In: Handbook of Cosmetic Science, and Technology, ed. by A.O. Barel, M. Paye,, H.I. Maibach (Marcel Dekker, New York 2005) pp., 5–18, R.C. Lindenschmidt, F.B. Anastasia, M. Dorta,, L. Bansil: Global cosmetic regulatory harmonization, Toxicology 160, 237–241 (2001), G.J. Nohynek, E. Antignac, T. Re, H. Toutain: Safety, assessment of personal care products/cosmetics, and their ingredients, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 243, 239–259 (2010), J. Vernon, T.A. Nwaogu: Comparative Study on, Cosmetics Legislation in the EU and Other Principal Markets with Special Attention to so-called, Borderline Products, prepared for European Commission, DG Enterprise (RPA, Loddon 2004) pp., 13–43, G. Pisacane: Cosmetics market regulation in Asian, countries, Househ. Pers. Care Today 4, 21–25, (2009), T. Srikanth, S.S. Hussen, A. Abha, S.G. Vasantharaju, S. Gummudavelly: A comparative view, , Part G | 44, , References

Page 22 :

1036, , Part G, , Application of Marine Biotechnology, , 44.79, , 44.80, , 44.81, , 44.82, , 44.83, , Part G | 44, , 44.84, , 44.85, , 44.86, , 44.87, , 44.88, , 44.89, , 44.90, , 44.91, , 44.92, , 44.93, , phycoerythrin from the microalga Porphyridium, cruentum, J. Biotechnol. 93(1), 73–85 (2002), R. Rossano, N. Ungaro, A. D’Ambrosio, G.M. Liuzzi, P. Riccio: Extracting and purifying Rphycoerythrin from Mediterranean red algae, Corallina elongata Ellis & Solander, J. Biotechnol., 101, 289–293 (2003), A. Khanafari, A. Saberi, M. Azar, G. Vossoghi,, S. Jamili, B. Sabbaghzadeh, B. : Extraction of astaxanthin esters from shrimp waste by chemical, and microbial methods, Iran. J. Environ. Health, Sci. Eng. 4(2), 93–98 (2007), T.S. Trung, P.T.D. Phuong: Bioactive compounds, from by-products of shrimp processing industry, in Vietnam, J. Food Drug Anal. 20, 194–197 (2012), J. Synowiecki, N.A. Al-Khateeb: Production, properties, and some new applications of chitin and, its derivatives, Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 43, 145–171, (2003), K. Kurita: Chitin and chitosan: Functional, biopolymers from marine crustaceans, Mar., Biotechnol. 8, 203–226 (2006), Z. Degim, N. Celebi, H. Sayan, A. Babül, D. Erdoğan, G. Take: An investigation on skin wound, healing in mice with a taurine-chitosan gel formulation, Amino Acids 22, 187–198 (2002), T. Nagai, Y. Araki, N. Suzuki: Collagen of the skin, of ocellate puffer fish (Takifugu rubripes), Food, Chem. 78, 173–177 (2002), N. Domoto, T. Koriyama, B.S. Chu, T. Tsuji:, Evaluation of the efficacy of orange roughy, (Hoplostetbus atlanticus) oil in subjects with dry, skin, Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 34, 322–327 (2012), S. Sekar, M. Chandramohan: Phycobiliproteins as, a commodity: Trends in applied research, patents, and commercialization, J. Appl. Phycol. 20, 113–, 136 (2008), S. Arad, A. Yaron: Natural pigments from red microalgae for use in foods and cosmetics, Trends, Food Sci. Technol. 3, 92–97 (1992), R. Bermejo, J.M. Álvarez-Pez, F.G. Acién,, E. Molina: Recovery of pure B-phycoerythrin, from the microalga Porphyridium cruentum,, J. Biotechnol. 93, 73–85 (2002), R. Bermejo, E.M. Talavera, C. del Valle,, J.M. Álvarez-Pez: C-phycocyanin incorporated into reverse micelles: A fluorescence study,, Colloids Surf. B 18, 51–59 (2000), P.J. Viskari, C.L. Colyer: Rapid extraction of phycobiliproteins from cultures cyanobacteria samples,, Anal. Biochem. 319, 263–271 (2003), Jaswir, D. Noviendri, R.F. Hasrini, F. Octavianti:, Carotenoids: Sources, medicinal properties and, their application in food and nutraceutical industry, J. Med. Plants Res. 5, 7119–7131 (2011), E. Christaki, E. Bonos, I. Giannenas, P. FlorouPaneri: Functional properties of carotenoids originating from algae, J. Sci. Food Agric. 93, 5–11, (2013), , 44.94, , 44.95, , 44.96, , 44.97, , 44.98, , 44.99, , 44.100, , 44.101, , 44.102, , 44.103, , 44.104, , 44.105, , 44.106, , 44.107, , D.H. Ngo, T.S. Vo, D.N. Ngo, I. Wijesekara, S.K. Kim:, Biological activities and potential health benefits, of bioactive peptides derived from marine organisms, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 51, 378–383 (2012), J. Peng, J.P. Yuan, C.F. Wu, J.H. Wang: Fucoxanthin, a marine carotenoid present in brown, seaweeds and diatoms: Metabolism and bioactivities relevant to human health, Mar. Drugs 9,, 1806–1828 (2011), G. Riccioni, L. Speranza, M. Pesce, S. Cusenza,, N. D’Orazio, M.J. Glade: Novel phytonutrient contributors to antioxidant protection against cardiovascular disease, Nutrition 28, 605–610 (2012), H. Maeda, M. Hosokawa, T. Sashima, K. Miyashita:, Dietary combination of fucoxanthin and fish, oil attenuates the weight gain of white adipose tissue and decreases blood glucose in, obese/diabetic KK-Ay mice, J. Agric. Food Chem., 55, 7701–7706 (2007), H. Maeda, M. Hosokawa, T. Sashima,, K. Murakami-Funayama, K. Miyashita: Antiobesity and anti-diabetic effects of fucoxanthin, on diet-induced obesity conditions in a murine, model, Mol. Med. Rep. 2, 897–902 (2009), K. Miyashita, H. Maeda, T. Tsukui, T. Okada,, M. Hosokawa: Anti-obesity effect of allene, carotenoids, fucoxanthin and neoxanthin from, seaweeds and vegetables, Acta Hortic. 841, 167–, 171 (2009), A.E. Batista González, M.B. Charles, J. ManciniFilho, A. Vidal Novoa: Seaweeds as sources of, antioxidant phytomedicines, Rev. Cubana Plant., Med. 14, 1–18 (2009), S.N. Sunassee, M.T. Davies-Coleman: Cytotoxic, and antioxidant marine prenylated quinones and, hydroquinones, Nat. Prod. Rep. 29, 513–535 (2012), E.M. Balboa, E. Conde, A. Moure, E. Falque,, H. Dominguez: In vitro antioxidant properties of, crude extracts and compounds from brown algae,, Food Chem. 138, 1764–1785 (2013), S. Ren, J. Li, H. Guan: The antioxidant effects of, complexes of tilapia fish skin collagen and different marine oligosaccharides, J. Ocean Univ. China, 9, 399–407 (2010), M. Foti, M. Piattelli, V. Amico, G. Ruberto: Antioxidant activity of phenolic meroditerpenoids from, marine algae, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol., 26, 159–164 (1994), Y.X. Li, S.K. Kim: Utilization of seaweed derived ingredients as potential antioxidants and, functional ingredients in the food industry: An, overview, Food Sci. Biotechnol. 20, 1464–1466, (2011), A.P. Rivera, M.M. Uy: In vitro antioxidant and, cytotoxic activities of some marine sponges collected off Misamis Oriental coast, Philippines,, E-J. Chem. 9, 354–358 (2012), J.T. Ryan, R.P. Ross, D. Bolton, G.F. Fitzgerald, C. Stanton: Bioactive peptides from mus-

Page 23 :