Page 2 :

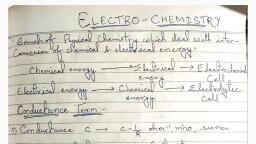

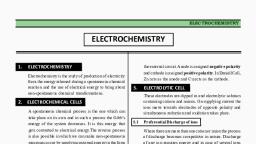

It is a branch of chemistry that deals with the, relationship between chemical energy and, electrical energy and their inter conversions.

Page 3 :

ELECTROCHEMICAL CELLS:, • These are devices that convert chemical energy of some, redox reactions to electrical energy., • They are also called Galvanic cells or Voltaic cells., • An example for Galvanic cell is Daniel cell., , The functions of a salt, bridge are:, 1. To complete the, electrical circuit., 2. To maintain the, electrical neutrality in, the two half cells.

Page 4 :

The reaction taking place in a Daniel cell is, Zn(s) + Cu2+(aq) → Zn2+ (aq) + Cu(s), This reaction is a combination of two half reactions:, , (i) Cu2+ + 2 e- → Cu(s) (reduction half reaction), (ii)(ii) Zn(s) → Zn2+ + 2 e- (oxidation half reaction), These two portions of the cell are also called half-cells or, redox couples., , The tendency of a metal to lose or gain electron when it, is in contact with its own solution is called electrode, potential., ➢When the concentrations of all the species involved in a halfcell is unity then the electrode potential is known as standard, electrode potential.

Page 5 :

•In a galvanic cell, the half-cell in which oxidation takes place is, called anode and it has a negative potential., •The other half-cell in which reduction takes place is called, cathode and it has a positive potential., LEFT, Oxidation, Anode, Negative electrode, , RIGHT, Reduction, Cathode, Positive electrode, , LOAN, •The c e l l p o t e nt i a l is the difference between the electrode, potentials (reduction potentials) of the cathode and anode., •The cell e l e c t r o mo t i v e f o r c e ( e mf ) of the cell is the, potential difference between the two electrodes, when no, current is flow through the cell.

Page 6 :

For Daniel cell, the cell representation is :, , Zn(s) / Zn 2 + (a q) // Cu 2 + (a q) / Cu(s ), while representing a galvanic cell,, •The anode is written on the left side and the cathode on the right side., •Metal and electrolyte solution are separated by putting a vertical line and ,, •A salt bridge is denoted by putting a double vertical line., , E cel l = E ri g h t – E l eft, Or,, E cel l = E R – E L

Page 7 :

Nernst Equation:, Nernst proposed an equation to relate the electrode potential of, an electrode (or, emf of a cell) with the electrolytic concentration., a) Nernst equation connecting electrode potential and electrolytic, concentration:, For the electrode reaction:, Mn+ (aq) + ne- → M(s), The Nernst equation is:, , at 298K, , Where, • E0 is the standard, electrode potential,, •n is the number of, electrons involved in the, cell reaction and, •[Mn+ ] is the concentration, of the species, M n+ .

Page 8 :

Nernst equation for Daniel Cell, , For Daniel cell, the electrode, reactionsare:, Cu2+ + 2 e- → Cu(s), (cathode), Zn(s) → Zn2+ + 2 e(anode)

Page 9 :

❑It can be seen that E(cell) depends on the concentration, of both Cu2+ and Zn2+ ions., ❑It increases with increase in the concentration of Cu 2+, ions and decrease in the concentration of Zn 2+ ions., ❑By converting the natural logarithm in Eq. to the base, 10 and substituting the values of R, F and T = 298 K, it, reduces to ,, E(cell) = E0(cell) – 0.059 log [Zn] 2+, 2, [Cu] 2+, For a general electrochemical reaction of the type:, a A + bB → cC + dD, Nernst equation at 298K can be written as, , E(cell) = E0 cell – RT ln[C]c[D]d, nF [A]a[B]b

Page 10 :

Equilibrium Constant from Nernst Equation, The concentration of Zn2+ keeps on increasing while the, concentration of Cu2+ keeps on decreasing. At the same time, voltage of the cell as read on the voltmeter keeps on decreasing., After some time, we shall note that there is no change in the, concentration of Cu2+ and Zn2+ ions and at the same time,, voltmeter gives zero reading. This indicates that equilibrium has, been attained., In this situation the Nernst equation may be written as:

Page 11 :

But at equilibrium,, , In general,

Page 12 :

Conductance of Electrolytic Solutions, 1. Resistance (R): The electrical resistance is the hindrance to the, flow of electrons. Its unit is ohm (Ω). The resistance of a, conductor is directly proportional to the length of the conductor, (Ɩ) and inversely proportional to the area of cross-section (A) of, the conductor., i.e., R α Ɩ /A, or,, R = a constant x Ɩ/A, or,, R = ρ x Ɩ/A,, where ρ (rho) is a constant called resistivity., Its unit is ohm-metre (Ω m) or ohm-centimetre (Ω cm)., 1 Ω m = 100 Ω cm,, 1 Ω cm = 10-2 Ω m, Resistivity is defined as the resistance offered by a conductor, having unit length and unit area of crosssection

Page 13 :

Conductance (G):, •It is the inverse of resistance., i.e. G = 1/R. Its unit is ohm-1 or mho or Siemens (S), Or,, G = 1 x A ρ Ɩ Or,, , G = ƙ x A/Ɩ, Where, ƙ is called conductivity., It is defined as the conductance of a conductor having unit, , length and unit area of cross-section., Its unit is ohm-1 m-1 or mho m-1 or S m-1 ., , 1 S cm-1 = 100 S m-1 1 S m-1 = 10-2 S cm-1

Page 14 :

Conductivity (ƙ) and Molar conductivity (λm), Conductivity is the conductance of a conductor having, unit length and unit area of cross-section., Its unit is ohm-1 m-1 or mho m-1 or Sm-1 ., , Molar conductivity is the conductivity of 1 mole of an, , electrolytic solution kept between two electrodes with, unit area of cross section and at a distance of unit length., Its unit is Ω-1cm2 mol-1 or S cm2 mol.-1, , .

Page 15 :

Variation of conductivity and Molar, conductivity with concentration (dilution) :, • Both conductivity and molar conductivity change with, the concentration of the electrolyte., • When a solution is diluted, its concentration decreases., , For both strong and weak electrolytes,, conductivity always decreases with dilution., • This is because conductivity is the conductance of, unit volume of electrolytic solution., • As dilution increases, the number of ions per unit, volume decreases and hence the conductivity, decreases.

Page 16 :

•For strong electrolytes, as dilution increases, the force of attraction, , between the ions decreases and hence the ionic mobility increases., So, molar conductivity increases., •When dilution reaches maximum or concentration approaches zero,, the molar conductivity becomes maximum and it is called the, limiting molar conductivity (λ0m)., •For both strong and weak electrolytes, the molar conductivity, , increase with dilution (or decrease with increase in concentration),, but due to different reasons.

Page 17 :

•For strong electrolytes, as dilution increases, the force of, attraction between the ions decreases and hence the ionic, mobility increases. So, molar conductivity increases., •When dilution reaches maximum or concentration approaches, zero, the molar conductivity becomes maximum and it is called, the limiting molar conductivity (λ 0m)., , •For weak electrolytes, as, dilution increases, the, degree of dissociation, increases., •So the number of ions and, hence the molar, conductivity increases.

Page 18 :

For strong electrolytes, the relation between λm and, concentration can be given as:, , λm = λ0m - A√c, , Where ‘c’ is the concentration and A is a constant depends on, temperature, the nature of the electrolyte and the nature of the, solvent., All electrolytes of a particular type have the same value for ‘A’., •For strong electrolytes, the value of λ 0m can be determined by the, extrapolation of the graph., , •But for weak electrolytes, it is not possible since the graph is not, a straight line. So their λ0m values are calculated by applying, Kohlrausch’s law of independent migration of ions.

Page 19 :

Kohlrausch’s law of independent migration of ions:, The law states that the limiting molar conductivity of an electrolyte, can be represented as the sum of the individual contributions of the, , anion and the cation of the electrolyte., Thus if an electrolyte on dissociation gives n(+) cations and, n(-) anions, its limiting molar conductivity is given as:, , Λ°m (NaCl) = λ°Na+ + λ°Cl–

Page 20 :

Faraday’s laws:, 1) Faraday’s first law :, It states that the amount of substance deposited or liberated at the, electrodes (m) is directly proportional to the quantity of electricity, (Q) flowing through the electrolyte., Mathematically,, m α Q Or,, m = zQ, Where z is a constant called electrochemical equivalent (ECE)., Z = equivalent weight/96500, But quantity of electricity is the product of current in ampere (I) and, time in second (t)., i.e. Q = It, Therefore, m= zIt, 1 Faraday is the charge of 1 mole of electron or it is the amount of, electricity required to deposit one gram equivalent of any substance., Its value is 96500 C/mol.

Page 21 :

Faraday’s second law:, It states that when same quantity of electricity is passed, through solutions of different substances, the amount of, substance deposited or liberated is directly proportional to their, , chemical equivalence., , Products of electrolysis, The products of electrolysis depend on the following factors:, , i) The nature of the electrolyte: The electrolyte may be in, molten state or in aqueous solution state.

Page 22 :

ii) The type of electrodes used: If the electrode is inert (e.g. Pt,, gold, graphite etc.), it does not participate in the electrode, , reaction. While if the electrode is reactive, it also participate in the, electrode reaction., iii) The different oxidising and reducing species present in the, electrolytic cell and their standard electrode potentials. Some of, , the electrochemical processes are very slow and they do not take, place at lower voltages. So some extra potential (called, overpotential) has to be applied, which makes such process more, difficult to occur

Page 23 :

Batteries, A battery is basically a galvanic cell in which the chemical energy of, a redox reaction is converted to electrical energy. They are of mainly, 2 types – primary batteries and secondary batteries., a) Primary cells: These are cells which cannot be recharged or, reused. Here the reaction occurs only once and after use over a, period of time, they become dead E.g. Dry cell, mercury button, cell etc., b) Secondary cells: A secondary cell can be recharged and, reused again and again. Here the cell reaction can be reversed, by passing current through it in the opposite direction., The most important secondary cell is lead storage cell, which, is used in automobiles and invertors.

Page 24 :

1. Dry Cell:, It is a compact form of Leclanche cell. It consists of a zinc container, as anode and a carbon (graphite) rod surrounded by powdered, manganese dioxide (MnO2) and carbon as cathode., , The space between the electrodes is filled by a moist paste of, ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) and zinc chloride (ZnCl2)., The electrode reactions are:, Anode : Zn(s) → Zn2+ + 2e–, Cathode: MnO2+ NH4 + + e–→ MnO(OH) + NH3, , Ammonia produced in this reaction forms a complex with Zn2+ and, thus corrodes the cell. The cell has a potential of nearly 1.5 V.

Page 25 :

2. Mercury cell, Here the anode is zinc – mercury amalgam and cathode is a paste, of HgO and carbon. The electrolyte is a paste of KOH and ZnO., The electrode reactions are:, , Anode reaction: Zn(Hg) + 2OH+ → ZnO(s) + H2O + 2e–, Cathode reaction: HgO + H2O + 2e– → Hg(l ) + 2OH–, The overall reaction is : Zn(Hg) + HgO(s) → ZnO(s) + Hg(l ), The cell has a constant potential of 1.35 V, since the overall, reaction does not involve any ion in solution

Page 27 :

On charging the battery, the reaction is reversed and PbSO4(s) on, anode and cathode is converted into Pb and PbO2, respectively., Another example for a secondary cell is nickel – cadmium cell., Here the overall cell reaction is, , Cd (s)+2Ni(OH)3 (s) → CdO (s) +2Ni(OH)2 (s) +H2O(l )

Page 28 :

Fuel cells :, These are galvanic cells which convert the energy of combustion, of fuels like hydrogen, methane, methanol, etc. directly into, , electrical energy., One example for fuel cell is Hydrogen – Oxygen fuel cell, which, is used in the Apollo space programme., , Here hydrogen and oxygen are bubbled through porous carbon, electrodes into concentrated aqueous sodium hydroxide solution., , To increase the rate of electrode reactions, catalysts like finely, divided platinum or palladium metal are filled into the electrodes.

Page 29 :

The electrode reactions are:, Cathode: O2(g) + 2H2O(l ) + 4e–→4OH– (aq), , Anode: 2H2 (g) + 4OH– (aq) → 4H2O(l) + 4e–, Overall reaction is: 2H2(g) + O2(g) ⎯→ 2H2O(l ), , Advantages of Fuel cells, 1. The cell works continuously as long, as the reactants are supplied., 2. It has higher efficiency as compared, to other conventional cells., 3. It is eco-friendly (i.e. pollution free), since water is the only product, formed., 4. Water obtained from H2 – O2 fuel cell, can be used for drinking.

Page 30 :

Corrosion:, It is the process of formation of oxide or other compounds of a metal, on its surface by the action of air, water-vapour, CO2 etc., Some common examples are: The rusting of iron, tarnishing of, silver, formation of green coating on copper and bronze (verdigris), , etc., Most familiar example for corrosion is rusting of iron. It occurs in, presence of water and air. It is a redox reaction., Here the iron is first oxidised to ferrous (Fe2+ ), then to ferric, , ions (Fe3+) and finally to hydrated ferric oxide (Fe2O3. x H2O),, which is called rust.

Page 31 :

Methods to prevent corrosion, 1. By coating the metal surface with paint, varnish etc., 2. By coating the metal surface with another electropositive, metal like zinc, magnesium etc. The coating of metal with zinc, , is called galvanisation and the resulting iron is called, galvanized iron., , 3. By coating with anti-rust solution., 4. An electrochemical method is to provide a sacrificial electrode, of another metal (like Mg, Zn, etc.) which corrodes itself but, , saves the object (sacrificial protection)