Page 1 :

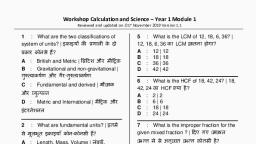

Chapter 4, , Integration, defined as a continuous summation process, is linked to dyferentiation by the fundamental theorem of calculus., , In everyday language, the word integration refers to putting things together,, while dgerentiation refers to separating, or distinguishing, things., The simplest kind of "differentiation" in mathematics is subtraction,, which tells us the difference between two numbers. We may think of differentiation in calculus as telling the difference between the values of a function at, nearby points in its domain., By analogy, the simplest kind of "integration" in mathematics is addition., Given two or more numbers, we can put them together to obtain their sum., Integration in calculus is an operation on functions, giving a "continuous, sum" of all the values of a function on an interval. This process can be, applied whenever a physical quantity is built up from another quantity which, is spread out over space or time. For example, in this chapter, we shall see that, the distance travelled by an object moving on a line is the integral of its, velocity with respect to time, generalizing the formula "distance = velocity x, time," which is valid when the velocity is constant. Other examples are that, the volume of a wire of variable cross-sectional area is obtained by integrating, this area over the length of the wire, and the total electrical energy consumed, in a house during a day is obtained by integrating the time-varying power, consumption over the day., , Summation, The symbol, , Cy=,ai is shorthand for, , a,, , + a, + . . + a,,., , To illustrate the basic ideas and properties of integration, we shall reexamine, the relationship between distance and velocity. In Section 1.1 we saw that, velocity is the time derivative of distance travelled, i.e.,, ~d - change in distance, velocity zz - At, change in time, , a, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 2 :

202, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , In this chapter, it will be more useful to look at this relationship in the form, , ad w velocity x ~ t ., , (2), To be more specific, suppose that a bus is travelling on a straight highway, and that its position is described by a function y = F ( t ) , where y is the, position of the bus measured in meters from a designated starting position,, and r is the time measured in seconds. (See Fig. 4.1.1.) We wish to obtain the, , 5ocJ'o, , 700", , 40, , 40, , L, , Figure 4.1.1. What IS the, pos~t~on, of the bus ~nterms, of its velocity?, , I 111L t c r i, , 10, , 70, , 1, , I, , position y in terms of velocity 0. In Section 2.5 we did this by using the, formula v = d y / d t and the notion of an antiderivative. This time, we shall go, back to basic principles, starting with equation (2)., If the velocity is constant over an interval of length A t , then the, approximation ( z )in equation (2) becomes equality, i.e., A d = c a t . This, suggests another easily understood case: suppose that our time interval is, divided into two parts with durations A t , and At, and that the velocity during, these time intervals equals the constants c , and c,, respectively. (This situation, is slightly unrealistic, but it is a convenient idealization.) The d~stancetravelled during the first interval is c , A t , and that during the second is c , A t 2 ;, thus, the total distance travelled is, A d = c, At,, , + c,At2, , Continuing in the same way, we arrive at the following result:, , If a particle moves with a constant velocity r , for a time interval S t , ,, c, for a time interval At,, c, for a time interval At,, . . . and velocity, c,, for time interval At,,, then the total distance travelled is, , ., , A d = c,At, +c,At,+, , u,At,+, , ..., , + c,,At,,., , In (3), the symbol "+ . . . + " is interpreted as "continue summing until the, last term o,, At,, is reached.", The bus in Fig. 4.1.1 moves with the following velocities:, , Example I, , 4 meters per second for the first 2.5 seconds., 5 meters per second for the second 3 seconds,, 3.2 meters per second for the third 2 seconds, and, 1.4 meters per second for the fourth 1 second., How far does the bus travel?, Solution, , We use formula (3) with n, , =4, , and, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 3 :

4.1 Summation, , 4,, u, = 5 ,, u, = 3.2,, u, = 1.4,, , U, =, , At,, , = 2.5,, , At,, , = 3,, , At,, , = 2,, , At,, , =, , 203, , 1, , to get, , Ad=4x2.5+5x3+3.2x2+, = 10+ 15 + 6 . 4 + 1.4, = 32.8 meters. B,, , 1.4x 1, , Integration involves a summation process similar to (3). T o prepare for the, development of these ideas, we need to develop a systematic notation for, summation. This notation is not only useful in the discussion of the integral, but will appear again in Chapter 12 on infinite series., Given n numbers, a , through a,, we denote their sum a ,, , + a, + . . . + a,, , by, , Here 2 is the capital Greek letter sigma, the equivalent of the Roman S (for, sum). We read the expression above as "the sum of a,, as i runs from 1 to n.", Example 2, , Solution, , (a) Find, , C:=,a,, if, , a l = 2, a2 = 3, a, = 4 , a4 = 6 . (b) Find, , (a) C : = , a , = a , + a , + a,+ a 4 = 2 + 3 + 4 + 6, , =, , 2:, , ,i2., , 15, , (b) Here a, = i2, so, , Notice that formula ( 3 ) can be written in summation notation as, , c c, a t , ., , =, , The letter i in (4) is called a dummy inde.~;we can replace it everywhere, by any other letter without changing the value of the expression. For instance,, n, , n, , a,, , and, , X=l, , a,, I =, , I, , have the same value, since both are equal to a , + . . ., A summation need not start a t I ; for instance, 6, , b, means, , i=2, , h,, , + a,,., , + h, + 6 , + b, + h,, , and, 3, , c, means, J=, , Example 3, , Solution, , Find, , c-,+c,+c~+c~+c~+c,., , -2, , ~i,,(k~ - k ) ., , 2 S , = , ( k 2 - k ) = ( 2 2 - 2 ) + (3', , -, , 3) + (4' - 4 ) + ( 5 2 - 5 ) = 2, , + 6 + 12 + 20, , = 40., , A, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 4 :

204, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , where m < n are integers, and a, are real numbers, let i take each integer, value such that m S i S n. For each such i, evaluate a, and add the, resulting numbers. (There are n - m + 1 of them.), We list below some general properties of the summation operation:, , Properties of Summation, , 2., , n, , n, , i=m, , i=m, , C cai= c 2 a, ,, , 3. If m & n and n, P, , where c is a constant., , + 1 < p, then, P, , n, , 4. If a, = C for all i with m S i 6 n, where C is some constant, then, n, , 2 a,=, , C(n - m, , + 1)., , i= m, , 5. If a,, , < b, for all i, , with m ,< i 6 n, then, , These are just basic properties of addition extended to sums of many numbers at a time. For instance, property 3 says that a,, a m + , . . . + ap =, (a,, . . . a,) + (an+ . . . + up),which is a generalization of the associative law. Property 2 is a distributive Iaw; property 1 is a commutative law., Property 4 says that repeated addition of the same number is the same as, multiplication; property 5 is a generalization of the basic law of inequalities: if, a < b and c < d, then a c \< b + d., A useful formula gives the sum of the first n integers:, , +, , +, , +, , ,+, , +, , +, , + +, , +, , To prove this formula, let S = C:= ,i = 1 2 . . . n. Then write S again, with the order of the terms reversed and add the two sums:, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 5 :

205, , 4.1 Summation, , Since there are n terms in the sum, the right-hand side is n(n, 2 S = n(n + I), and S = n(n + I)., , 4, , Exampie 4, , Solution, , Example 5,, , Solution, , Example 6, , Solution, , + l),, , so, , Find the sum of the first 100 integers.', We substitute n, = 5050. A, Find the sum 4, , =, , +, , 100 into S = n(n, , + l),, , giving, , + . 100 . 101, , = 50, , . 101, , + 5 + 6 + . + 29., , This sum is ~ ! l , i . We may write it as a difference ~ ! l , i C j = , i using either, "common sense" or summation property 3. Using formula (5) twice gives, , Find ~ j % ( j 2)., We use the summation properties as follows:, , 102, , =, , 2, , C j - 21 j -, , j= 1, , ;=, , = +(102)(103) -, , 2(100), , (properties 3 and 4), , 3 - 200, , (formula (5)), , = 5050., , We can also do this problem by making the substitution i = j - 2. As j runs, from 3 to 102, i runs from 1 to 100, and we get, , The second method used in Example 6 is usually best carried out by thinking, about the meaning of the notation in a given problem. However, for reference,, we record the general formula for substitution of an index: With the substituq,, tion i = j, , +, , The following example illustrates a trick that utilizes cancellation., Example 7, , Solution, , Show that, , Cr=,[i3 - ( i - 113]= n3, , The easiest way to do this is by writing out the sum:, , + . . . + [(n - 1)' - (n - 2))] + [n3 - (n - I)'], and observing that we can cancel l 3 with - 13, Z3 with - 23, 33 with - 33, and, so on up to (n - 1)3 with -(n - l)3. This leaves only the terms, , ', , A famous story about the great mathematician C. F. Gauss (1777-1855) concerns a task his, class had received from a demanding teacher in elementary school. They were to add up the first, 100 numbers. Gauss wrote the answer 5050 on his slate immediately; had he derived, S = f n ( n + 1) in his head at age 10?, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 6 :

206, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , The kind of sum encountered in Example 7 is called a telescoping, or, collapsing, sum. A similar argument proves the result in the following box., , The next example uses summation notation to retrieve a result which may, already be obvious, but the idea will reappear later in the fundamental, theorem of calculus., Suppose that the bus in Fig. 4.1.1 is at position yi at time ti, i = 0, . . . , n, and, that during time interval ( t i - , ,ti), the velocity is a constant, , Example 8, , Using a telescoping sum, confirm that the distance travelled equals the, difference between the final and initial position., Solution, , By formula (37, the distance travelled is, , Since vi = Ayi/Ati, we get, , This is a telescoping sum which, by (7), equals y, - y o ; i.e., the final position, minus the initial position (see Fig. 4.1.2 where n = 3). A, , 'y 1 1, --------A>,,, , Figure 4.1.2. Motion of the, bus in Example 8 (n = 3)., , Total, distance, travelled, , V, l'otal tlnie, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 7 :

4.2 Sums and Areas, , 207, , Exercises for Section 4.1, In Exercises 1-4, a particle moves along a line with the, given velocities for the given time intervals. Compute, the total distance travelled., 1. 2 meters per second for the first 3 seconds,, 1.8 meters per second for the second 2 seconds,, 2.1 meters per second for the third 3 seconds,, 3 meters per second for the fourth 1.5 seconds., 2. 3 meters per second for the first 1.5 seconds,, 1.2 meters per second for the second 3 seconds,, 2.1 meters per second for the third 2.4 seconds,, 4 meters per second for the fourth 3 seconds., 3. 8 meters per second for the first 1.2 seconds,, 10 meters per second for the second 3.1 seconds,, 12 meters per second for the third 4.2 seconds., 4. 2 meters per second for the first 8.1 seconds,, 3.2 meters per second for the second 2 seconds,, 4.6 meters Der second for the third 1.1 seconds., Find the sums in Exercises 5-8., 6. Z ; = , i 3, 5. 24- l(i2+ 1 ), 7 . ~ 5 i- ( i - 1), 8. C!=l i ( i - 2), Find the sums in Exercises 9-12., 9. 1 + 2 + . . . + 2 5, 10. 3 + 4 + . . . + 3 9, 11. ~ 4 5 _ , i, 12. ~ 3 9 , , i, Find the sums in Exercises 13- 16., 14. CjO=8,(j - 7 ), 13. C F 4 ( j - 3 ), - i2] 16. Cl?l[(i + 1)' - i s ], 15. C39-,[(i +, 17. Find Cj, - 2 j3., 18. Find C ) z 10M) j5., 19. Find C F l ( j + 6)., 20. Find CF=-20 k., 2 1. Find a formula for I=$=, i, where rn and n are, positive integers., 22. Find 2::,ai, where ai is the number of days in, the ith month of 1987., 23. Show that ELFlI / ( I + k 2 ) < 1000., 24. Show that ~ : M ) , 3 / ( 1+ i ) < 300., Find the telescoping sums in Exercises 25-28., 25. c!M),[i4- ( i - 114], 26. 2;: {(3i12- [3(i - l)I2), 27. c;'2pl[(i 2)2 - (i + l)'], 28. 2:: ,[(i + 3)' - ( i + 21'1, , 29. Draw a graph like Fig. 4.1.2 for the data in, Exercise I., 30. Draw a graph like Fig. 4.1.2 for the data in, Exercise 2., Find the sums in Exercises 3 1-40., 31. 2 i E O ( 3 k- 2), 32. 27=,(2i + 1), 33. C", =,[(k, + 1)4 - k4], 34. 2;: ,[(k + 1)' - k 8 ], 35. ~ ! ? , [ ( i+ 2)2 - ( i - I)'], 36., ,[(2i+ 213 - (2q3], 37. 2;: _30[i5+ i + 21, 38. 2:: -,,[I9 + 51' - 1315 + I ], 39. Cq=,2', 40. -, , x;!, , a41. By the method of telescoping sums, we have, , C [ ( i + 1)3 - i 3 ] = ( n + I ) ~ 1.i= 1, , - i3 = 3i2 + 3i + 1 and use, (a) Write ( i +, properties of summation to prove that, , (b) Find a formula for, , in terms of m and n., (c) Using the method and result of (a), find a, formula for 27=,i3. (YOUmay wish to try, guessing an answer by experiment.), +42. (a) Prove that, , +, , n, , 2 i ( i + 1 ) = -31n ( n + 1)(n + 2 ), , i= l, , by writing, , and using a telescoping sum., (b) Find 2:-,i(i + l ) ( i 2)., (c) Find C:=,[l/i(i + I)]., , +, , Sums and Areas, Areas under graphs can be approximated by sums., , In the last section, we saw that the formula for distance in terms of velocity is, Ad = C',',,viAtiwhen the velocity is a constant vi during the time interval, (ti-, ,ti). In this section we shall discuss a geometric interpretation of this fact, which will be important in the study of integration., Let us plot the velocity of a bus as a function of time. Suppose that the, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 8 :

208, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , total time interval in question is [ a ,b]; i.e., t runs from a to b, and this interval, is divided into n smaller intervals so that a = to < t , < . . . < t, = b. The ith, . ~ form of u is, interval is ( t i - , ,ti), and v is a constant ui on this i n t e r ~ a l The, shown in Fig. 4.2.1 for n = 5., , Figure 4.2.1. The velocity, of the bus., , to, , r ? [ 3, , f4, , ts, , We notice that viAti is exactly the area of the rectangle over the ith, interval with base At, and height vi (the rectangle for i = 3 is shaded in the, figure). Thus,, n, , Ad, , vi At, is the total area of the rectangles under the graph of v., , =, i= l, , Figure 4.2.2. The region, under the graph off on, [a,61., , This suggests that the problem of finding distances in terms of velocities, should have something to do with areas, even when the velocity changes, smoothly rather than abruptly. Turning our attention to areas then, we go, back to the usual symbol x (rather than t ) for the independent variable., The area under the graph of a functionf on an interval [ a ,b] is defined to, be the area of the region in the plane enclosed by the graph y = f(x), the x, axis, and the vertical lines x = a and x = b. (See Fig. 4.2.2.) Here we assume, that f(x) > 0 for x in [a,b]. (In the next section, we shall deal with the, possibility that f might take negative values.), Let us examine certain similarities between properties of sums and areas., ,ai of sums, there corresponds the, To the property Cf=,ai = C:'=mai+ Cf=n+, additive property of areas: if a plane region is split into two parts which, overlap only along their edges, the area of the region is the sum of the areas of, the parts. (See Fig. 4.2.3.) Another property of sums is that if a, S bi for, , Figure 4.2.3. Area (A) =, Area (A ,) t Area (A2)., , Figure 4.2.4., Area ( A ) > Area (B)., , We are deliberately vague about the value of u at the end points, when the bus must suddenly, switch velocities. The value of Ad does not depend on what v is at each t,, so we can safely ignore, these points., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 9 :

4.2 Sums and Areas, , Figure 4.2.5. The graph of, a step fynction on [a, b], with n = 3., , Example 1, , Solution, , 209, , i = m,m + 1, . . . , n, then C:=,ai < 'jJ,,b,; the counterpart for areas is the, inclusion property: if one plane region is contained in another, the containing, region has more area. (See Fig. 4.2.4.), The connection between areas and sums becomes more explicit if we, consider step functions. A function g on the interval [a, b ] is called a step, function if [a, b ] can be broken into smaller intervals (called subintervals) with, g constant on each part. More precisely, there should be numbers x,,, x , , . . . , x,, with a = x 0 < x , < x 2 <, < x , - , < x , = b , such that g is, constant on each of the intervals ( x , , ~ , )( x, ,,x,), . . . , ( x , - , ,x,), as in Fig., 4.2.5. The values of g at the endpoints of these intervals will not affect any of, our calculations. The list (x,, x , , . . . , x,) is called apartition of [a, b ] ., , Draw a graph of the step function g defined on [2,4] by, , The graph of g on [2,2.5]is a horizontal line with height 1 on this interval. The, endpoints on the graph are drawn as solid dots to indicate that g takes the, value 1 at the endpoints x = 2 and x = 2.5. Continuing through the remaining, subintervals and using open dots to indicate endpoints which do not belong to, the graph, we obtain Fig. 4.2.6. A, , Figure 4.2.6. The graph of, the step function g in, Example 1., , Figure 4.2.7. The shaded, area is the sum of k,Ax,,, k, Ax2 and k, Ax,., , If a step function is non-negative, then the region under its graph can be, broken into rectangles, and the area of the region can be expressed as a sum., It is common to write Ax, for length xi - x i - , of the ith partition interval; if, the value of g on this interval is k , 2 0, then the area of the rectangle from, x i - , to xi with height k , is k i Ax,. Thus the total area under the graph is, k, Ax, + k , A x , + . . + k , Ax, = Cy-',,kiAx,, as in Fig. 4.2.7., , -, , Example 2, , What are the xi's, Ax,'s, and k,'s for the step function in Example l? Compute, the area of the region under its graph., , Solullon, , Looking at Figs. 4.2.6 and 4.2.7, we begin by labelling the left endpoint as x,;, i.e., x, = 2. The remaining partition points are x , = 2.5, x , = 3.5, and x , = 4., The Axj's are the widths of the intervals: Ax, = x , - x, = 0.5, Ax, = 1 , and, Ax, = 0.5. Finally, the ki9s are the heights of the rectangles: k, = 1, k , = 3,, and k , = 2. The area under the graph is, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 10 :

210, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , If each k, is positive (or zero), the area under the graph of g is, , In deriving our formula for the area under the graph of a step function, we, used the fact that the area of a rectangle is its length times width, and the, additive property of areas. By using the inclusion property, we can find the, areas under graphs of general functions by comparison with step functionsthis idea, which goes back to the ancient Greeks, is the key to defining the, integral., Given a non-negative functionf, we wish to compute the area A under its, graph on [ a ,b]. A lower sum for f on [ a ,b] is defined to be the area under the, graph of a non-negative step function g for which g(x) < f(x) on [ a ,b]. If, g(x) = k, on the ith subinterval, then the inclusion property of areas tells us, that C:=, k, Ax, < A . (Fig. 4.2.8)., , Figure 4.2.8. The shaded, area Cy=,k, Ax, is a lower, sum for f on [ a ,b]., , Figure 4.2.9. The shaded, area C,"= ,I, Axj is an upper, sum for f on [ a ,b]., , Similarly, an upper sum for f on [ a ,b] is defined to be, ,l.AxJ, where h, is a step function with f(x) < h(x) on [ a ,b], and h(x) = I, on the jth subinterval of a partition of [ a ,b] (Fig. 4.2.9). By the inclusion property for areas,, A < C,"= ,l, Ax,, so the area lies between the upper and lower sums., , XI"!, , Example3, , Let f ( x ) = x 2 + 1 for O, , < x < 2., , Let, , (2, , O < x <+,, , Draw a graph showing f(x), g(x), and h ( x ) . What upper and lower sums for f, can be obtained from g and h?, Solution, , The graphs are shown in Fig. 4.2.10., For g we have Ax, = 1, k, = O and Ax, = 1, k, = 2. Since g(x) < f (x) for, all x in the open interval (0,2) (the graph of g lies below that off), we have as, a lower sum,, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 11 :

4.2 Sums and Areas, , 211, , Figure 4.2.10. The area, under the graph of h is a n, upper sum for f ; the area, under the graph of g is a, lower sum., , For h we have A x , = 4 , I, = 2, Ax, = f , 1, = 4, and Ax, = $, l3 = 5 . Since, the graph of h lies above that o f f , h(x) > f(x) for all x in the interval (0,2),, we get the upper sum, , Using partitions with sufficiently small subintervals, we hope to find step, functions below and above f such that the corresponding lower and upper, sums are as close together as we wish. Notice that the difference between, lower and upper sums is the area between the graphs of the step functions (Fig., 4.2.1 1). We expect this area to be very small if the subintervals are small, enough and the values of the step functions are close to the values off., , Figure 4.2.111. The dark, shaded area is the, difference between upper, and lower sums for f on, [a,b ] .The area under the, graph is between the upper, and lower sums., , Suppose that there are lower sums and upper sums which are arbitrarily, close to one another. Then there can only be one number A such that, L < A < U for every lower sum L and every upper sum U, and this number, must be the area under the graph., , To calculate the area under the graph of a non-negative function f, we, try to find upper and lower sums (areas under graphs of step functions, lying below and above f) which are closer and closer together. (See, Example 6 below for a specific instance of what is meant by "closer and, closer.") The area A is the number which is above all the lower sums and, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 12 :

212, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , What we have done here for areas has a counterpart in our distance-velocity, problem. Suppose that v = f(t) defined for a < t < b gives the velocity of a, moving bus as a function of time, and that there is a partition ( t o ,t,, . . . , t,), of [a,b] and numbers k,, . . . , k, such that k, < f(t) for t in the ith interval, (ti-,,ti). Taking for granted that a faster moving object travels further in a, given time interval, we may conclude that the bus travels a distance at least, ki(ti - ti- ,) in the ith time interval. Thus the total distance travelled must be, at least k, At, + - . + k, At, = Cy=,ki Ati (where, as usual, we write Ati for, ti - t i - ,), so we have a lower estimate for the distance travelled between t = a, and t = b. Similarly, if we know that f(t) < li on (ti-,,ti) for some numbers, E l , . . . , I,, we get an upper estimate C?=,IiAti for the distance travelled. By, making the time intervals short enough we hope to be able to find ki and li, close together, so that we can estimate the distance travelled as accurately as, we wish., Example 4, , Solution, , The velocity of a moving bus (in meters per second) is observed over periods, of 10 seconds, and it is found that, 4<v<5, when 0 < t < 10,, when 10 < t < 20,, 5.5 < v < 6.5, when 20 < t < 30., 5 < v < 5.7, Estimate the distance travelled during the interval 0 < t < 30., , A lower estimate is 4 - 10 + 5.5 . 10 + 5 - 10 = 145, and an upper estimate is, 5 . 10 + 6.5 - 10 5.7 - 10 = 172, so the distance travelled is between 145 and, 172 meters. A, , +, , Example 5, , The velocity of a snail at time t seconds is (0.001)(t2+ I ) meters per second at, time t. Use the calculations in Example 3 to estimate how far the snail crawled, between t = 0 and t = 2., , Solution, , We may use the comparison functions g and h in Example 3 if we multiply, their values by 0.001 (and change x to t). The lower sum and upper sum are, also multiplied by 0.001, and so the distance crawled is between 0.002 and, 0.00733 . . . meters, i.e., between 2 and 74 millimeters. ~(r,, When we calculate derivatives, we seldom use the definition in terms of limits., Rather, we use the rules for derivatives, which are much more efficient., Likewise, we will not usually calculate areas in terms of upper and lower sums, but will use the fundamental theorem of calculus once we have learned it., Now, however, to reinforce the idea of upper and lower sums, we shall do one, area problem "the hard way.", , Example 6, , Solution, , Use upper and lower sums to find the area under the graph of f(x), [0, 11., , =, , x on, , The area is shaded in Fig. 4.2.12., We will look for upper and lower sums which are close together. The, simplest way to do this is to divide the interval 10, I] into equal parts with a, partition of the form (0,l/n,2/n, . . . , (n - l)/n, 1). A step function g(x), below f(x) is given by setting g(x) = (i - I)/n on the interval [(i - l)/n, i/n),, while the step function with h(x) = i/n on ((i - l)/n,i/nj is above f(x) (Fig., 4.2.13)., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 13 :

4.2 Sums and Areas, , 2113, , The difference between the upper and lower sums is equal to the total, area of the chain of boxes in Fig. 4.2.14, on which both g(x) and h ( x ) are, graphed. Each of the n boxes has area (1 / n ) . ( 1 / n ) = 1/ n 2 , so their total area, is n . ( 1 / n 2 ) = 1/ n , which becomes arbitrarily small as n + CQ, so we know, that the area under our graph will be precisely determined. To find the area,, we compute the upper and lower sums. For the lower sum, g(x) = (i - l ) / n, = ki on the ith subinterval, and Ax, = I / n for all i, so, , Y, , n, , Figure 4.2.12. The region, under the graph of f ( x ) = x, on [O, I]., , xk,Axi=, i= 1, , x -' -. I, , i=l, , n, , I =I, , n, , n2, , i(i-l)=, , The upper sum is, , I, Figure, , 4.2.14. Difference, between the upper and, lower sums., , Figure 4.2.13. Lower and upper sums for f(x) = x on [0, 11., , The area under the graph is the unique number A which satisfies the, inequalities 1 / 2 - 1/2n < A < 1/2 1/2n for all n (see Fig. 4.2.15). Since, the number 1 satisfies the condition, we must have A = A, , +, , 0, , L-L L 1, 7, , 211, , 7, , -c, , I, , 1, , lt?;, , Figure 42-15. The area lies, in the interval [ 1 / 2 - 1/ 2 n ,, +, for all n. The, length of this interval -0, as n-oo., , 4., , The result of Example 6 agrees with the rule from elementary geometry that, the area of a triangle is half the base times the height. The advantage of the, method used here is t h t itd~hbeapplied to more general graphs. (Another case, is given in Exercise 20.) This method was used extensively during the century, before the invention of calculus, and is the basis for the definition of the, integral., , Exercises for Section 4.2, Draw the graphs of the step functions in Exercises 1-4., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 14 :

214, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , In Exercises 5-8 compute the xi's, Axi9s,and k,'s for the, indicated step function and compute the area of the, region under its graph., 5. For g in Exercise 1., 6. For g in Exercise 2., 7. For g in Exercise 3., 8. For g in Exercise 4., In Exercises 9 and 10, draw a graph showing f, g, and h, and compute the upper and lower sums for f obtained, from g and h ., 9. f(x) = x2, 1 < X < 3;, , In Exercises 15-18, use upper and lower sums to find, the area under the graph of the given function., 15. f(x) = x for 1 < x < 2., 16. f(x)==2x for 0 < x < 1., 17. f(x) = 5x for a < x < b, a > 0., 18. f(x) = x + 3 for a < x < 6 , a > 0., , 19. Using upper and lower sums, find the area under, the graph of f(x) = 1 - x between x = 0 and, x = 1., *20. Using upper and lower sums, show that the area, under the graph of f(x) = x 2 between x = a and, x = b is ?j-(b3- a3). (YOUwill need to use the, result of Exercise 41(a) from Section 4.1.), x,, 1<x<2., Find the area under the graph off on [O, 21, using, the results of the Exercises 15 and 20., 922. Let, , 11. The velocity of a moving bus (in meters per, second) is observed over periods of 5 seconds, and it is found that, , 5.0 < v < 6.0, when 0 < t < 5,, 4.0 < v < 5 5, when 5 < t < 10,, 6 . 1 ~ 0 ~ 7 . 2 when 1 0 < t < 1 5 ,, when 15 < t < 20., 3.2 < v < 4.7, Estimate the distance travelled during the interval t = 0 to t = 20., 12. The velocity of a moving bus (in meters per, second) is observed over periods of 7.5 seconds, and it is found that, when 0 < t < 7.5,, 4.0 < u < 5.1, when 7.5 < t < 15,, 3.0 g v g 5.0, when 15 < t < 22.5,, 4.4 < v < 5.5, when 22.5 < t < 30., 3.0 < v < 4.1, Estimate the distance travelled during the interval t = 0 to t = 30., 13. The velocity of a snail at time t is (0.002)t2, meters per second at time t . Use the functions g, and h in Exercise 9 to estimate how far the snail, crawled between t = 1 and t = 3., 14. The velocity of a snail at time t is given by, (0.0005)(t3+ 1) meters per second at time t. Use, the functions g and h in Exercise 10 to estimate, how far the snail crawled between t = 1 and, t = 3., , Using the results of Exercises 17 and 19, find the, area under the graph off on [0,4]., +23. By combining the results of Example 6 and Exercise 20, find the area of the shaded region in Fig., 4.2.16. (Hint:Write the area as a difference of, known areas.), , Figure 4.2.16. Find the, shaded and striped areas., , *24. Using the results of previous exercises, find the, area of the striped region in Fig. 4.2.16., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 15 :

4.3 The Definition of the Integral, , 215, , 4.3 The Definition, , of the integral, The integral of a function is a "signed" area., , In the previous section, we saw how areas under graphs could be approximated by the areas under graphs of step functions. Now we shall extend this, idea to functions that need not be positive and shall give the formal definition, of the integral., Recall that if g is a step function with constant value k, > 0 on the, interval ( x i _, , x i ) of width Ax, = xi - xi- then the area under the graph of g, is, , ,,, , n, , Area, , =, , 2 k, Ax, ., i= l, , Figm4.3.1. The product, is the negative of the, shaded area., , This formula is analogous to the formula for distance travelled when the, velocity is a step function; see formula (31, Section 4.1. In that situation, it is, reasonable to allow negative velocity (reverse motion). Likewise, in the area, formula we wish to allow negative k,. To do so, we shall have to interpret, "area" correctly. Suppose that g ( x ) is a negative constant k, on an interval of, width Ax,. Then k, Ax; is the negative of the area between the graph of g and, the x axis on that interval. (See Fig. 4.3.1.), To formalize this idea, we introduce the notion of signed area. If R is any, region in the xy plane, its signed area is defined to be the area of the part of R, lying above the x axis, minus the area of the part !ying below the axis., If f is a function defined on the interval [ a ,b], the region between the, graph off and the x axis consists of those points ( x , y) for which x is in [ a ,b], a n d y lies betwen 0 and f ( x ) . It is natural to consider the signed area of such a, region, as illustrated in Fig. 4.3.2. For a step function g with values k, on, intervals of length Ax,, the sum C:=,k, Ax, gives the signed area of the region, between the graph of g and the x axis., , Figure 4.3.2. The signed, area between the graph off, and the x axis on [ a ,b] is, regions, the area of the, minus the area of the regions., , +, , minus the area of the portion below the x axis., For the region between the x axis and the graph of a step function, g , this signed area is C:= k, Ax,., , ,, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 16 :

216, , Ghariplter 4 The Integral, , Example I Draw a graph of the step function g on [O,1] defined by, , Compute the signed area of the region between its graph and the x axis., , Solution, , 't, , The graph is shown in Fig. 4.3.3. There are three intervals, with A x , = f ,, Ax,= - I3 = 1-,, 12 and Ax 3 -- 1 - 14 = I, 4 ; k , = -2, k2 = 3, and k 3 = 1. Thus, the signed area is, 3, , k,Axl= ( - 2 ) ( f ), , + (3)(&) + ( I ) ( + ), , = -f, , + $ + 4= 2 . A, , r=l, , --C, , The counterpart of signed area for our distance-velocity problem is directed, distance, explained as follows: If the bus is moving to the right, then u > O, and distances are increasing. If the bus is moving to the left, then v < O and, the distances are decreasing. In the formula Ad = C ~ = , v , A t ,Ad, , is the, displacement, or the net distance the bus has moved, not the total distance, travelled, which would be C:= ,lull At. Just as with signed areas, movement to, the left is considered negative and is subtracted from movement to the right., (See Fig. 4.3.4.), , Figwe 4.3.3. The graph of, the step function in, Example 1., , rnovemerit, to left, , F i w e 4.3.4. Ad is the, displacement; i.e., net, distance travelled., , To find the signed area between the graph and the x axis for a function, which is not a step function, we can use upper and lower sums. Just as with, positive functions, if g is a step function lying below f, i.e., g ( x ) < f ( x ) for x, in [ a ,b], we call, , L=, , 2 k, Ax,, , a lower sum for f. Likewise, if h is a step function lying above f, with values, on intervals of width Ax, for j = 1, . . . , m , then, , I,, , is an upper sum for f. If we can find L's and U's arbitrarily close together,, lying on either side of a number A , then A must be the signed area between, the graph off and the x axis on [ a ,61. (See Fig. 4.3.5.), , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 17 :

4.3 The Definition of the Integral, , 217, , Figure 4.3.5. The signed, area of the region R lies, between the upper and, lower sums., , We are now ready to define the integral of a function f., Definition, , Let f be a function defined on [ a ,b]. We say that f has an integral or that f is, integrable if upper and lower sums for f can be found which are arbitrarily, close together. The number I such that L < I < U for all lower sums L and, upper sums U is called the integral off and is denoted, , We call jthe integral sign, a, b , the endpoints or limits of integration, and f the, integrand., The precise meaning of "afbitrariiy close together'' is the same as in Example, 6, Section 4.2, namely, that there should exist sequences Ln and Un of lower, and upper sums such that limn,,(Un - Ln) = 0. (Limits of sequences will be, treated in detail in Chapter 11.), , Given a function f on [ a ,b], the integral off, if it exists, is the number, , which separates the upper and lower sums. This number is the signed, , The notation for the integral is derived from the notation for sums. The Greek, letter C has turned into an elongated S ; ki and $ have turned into function, values f ( x ) ; Axi has become d x ; and the limits of summation (e.g., i goes from, 1 to n ) have become limits of integration:, , Just as with antiderivatives, the "x" in "dx" indicates that x is the variable of, integration., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 18 :

218, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , Example 2, , Compute JP3f(x)dx for the function f sketched in Fig. 4.3.6. How is the, integral related to the area of the shaded region in the figure?, , Figure 4.3.6. The signed, area of the shaded region is, an integral., , Solullon, , The integral, , 2:J, , f(x)dx is the signed area of the shaded region., , f(x)dx= (1)(1), Example 3, , + (-1)(2) + (2)(2) = 1 - 2 + 4 =, , 3., , Write the signed area of the region in Fig. 4.3.7 as an integral., , Figure 4.3.7. The signed, area of this region equals, what integral?, , Solution, , The region is that between the graph of y, x = 1, so the signed area is, , =, , x3 and the x axis from x, , = -, , 4 to, , The next example shows how upper and lower sums can be used to approximate an integral. (In Chapter 6, we will learn how to compute this integral, exactly.), Example 4, , Using a division of the interval [ l ,2] into three equal parts, find, , (1 / x ) dx to, , &, &, we must find lower and upper sums which, , within an error of no more than, Solution, , X2, , To estimate the integral within, are within, of one another. We divide the interval into three equal parts and, use the step functions which give us the lowest possible upper sum and highest, possible lower sum, as shown in Fig. 4.3.8. For a lower sum we have, , +, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 19 :

4.3 The Definition of the Integral, , Figure, 4.3.8. Illustrating, -, , upper and lower sums for, I / x on [1,2]., , 1, , I, , ,, , ,, , ,, , 1, , 413, , 513, , ?, , 219, , *, Y, , For an upper sum we have, , It follows that, , Since the integral lies in the interval [%,%I, whose length is +,we may take, the midpoint % = as our estimate; it will differ from the true integral by no, = &, which is less than &. A, more than, , 4, , We have been calculating approximations to integrals without knowing, whether some of those integrals actually exist or not. Thus it may be, reassuring to know the following fact whose proof is given in more advanced, cour~es.~, Existence, , Iff is continuous on [ a ,b],then it has an integral., In particular, all differentiable functions have integrals, but so do step, functions and functions whose graphs have corners (such as y = 1x1); thus,, integrability is a more easily satisfied requirement than differentiability or, even continuity. The reader should note, however, that there do exist some, "pathological" functions that are not integrable. (See Exercise 36)., It is possible to calculate integrals of functions which are not necessarily, positive by the method used in Example 6 of the previous section, but this is a, tedious process. Rather than doing any such examples here, we shall wait until, we have developed the machinery of the fundamental theorem of calculus to, assist us., Let us now interpret the integral in terms of the distance-velocity, problem. We saw in our previous work that the upper and lower sums, represent the displacement of vehicles whose velocities are step functions and, which are faster or slower than the one we are studying. Thus, the displaceSee, for instance, Calculus Unlimited by J . Marsden and A. Weinstein, Benjamin/Cummings, (1981), p. 159, or one of the other references given in the Preface., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 20 :

220, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , ment, like the integral, is sandwiched between upper and lower sums for the, velocity function, so we must have, displacement =, , Example 5, , ib/(r), dt., , A bus moves on the line with velocity v, Write formulas in terms of integrals for:, , = ( t 2 - 4t, , + 3) meters per, , (a) the displacement of the bus between t = 0 and t = 3;, (b) the actual distance the bus travels between t = 0 and t, Solution, , second., , = 3., , +, , (a) The displacement is ,$(t2 - 4t 3)dt., (b) We note that v can be factored as ( t - l ) ( t - 3), so it is positive on (0,1), and negative on (1,3). The total distance travelled is thus, , We close this section with a discussion of a different approach to the integral,, called the method of Riemann sums. Later we shall usually rely on the step, function approach, but Riemann sums are also widely used, and so you, should have at least a brief exposure to them., The idea behind Riemann sums is to use step functions to approximate, the function to be integrated, rather than bounding it above and below. Given, a function f defined on [ a ,b] and a partition (x,,x,, . . . , x,) of that interval,, we choose points c,, . . . , c, such that ci lies in the interval [xi- ,,xi]. The step, function which takes the constant value f(ci) on (xi- ,,xi)is then an approximation to /; the signed area under its graph, namely,, , is called a Riemann sum.4 It lies above all the lower sums and below all the, upper sums constructed using the same partition, so it is a good approximation to the integral off on [a, b] (see Fig. 4.3.9). Notice that the Riemann sum, , Figure 4.3.9. The area of, the shaded region is a, Riemann sum for f on, [ a , bl., , is formed by "sampling" the values off at points c,, . . . , c,, "weighting" the, samples according to the lengths of the intervals from which the ci's are, chosen, and then adding., If we choose a sequence of partitions, one for each n, such that the, lengths Ax, approach zero as n becomes larger, then the Riemann sums, approach the integral JY(x)dx in the limit as n + co.From this and Fig. 4.3.9,, we again see the connection between integrals and areas., Just as the derivatives may be defined as a limit of difference quotiehts,, so the integral may be defined as a limit of Riemann sums; the integral as, defined this way is called the Riemann integral., After the German mathematician Bernhard Riemann (1826-1866)., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 21 :

4.3 The Definition of the Integral, , 221, , Choose, for each n, a partition of [a,b] into n subintervals such that the, maximum of Ax, in the nth partition approaches zero as n + w . If c, is a, point chosen in the interval [ x ,- ,xi], then, , ,, , Example 6, Solution, , Write, , 6', , x 3 d x as a limit of sums., , As in Example 6, Section 4.2, divide [0,1] into n equal parts by the partition, (0,l/n, 2/n,. . . ,(n - l)/n, 1). Choose ci= i/n, the right endpoint of the, interval [(i - l)/n, i/n]. (We nay choose any point we wish; the left endpoint, or midpoint would have been just as good.) Then with f ( x ) = x 3 , we get, , Therefore,, 1, lim -, , 9 So x 3 d x ., i3=, , 1, , "-)an4 ;= 1, , Thus, we can find fAx3dx if we can evaluate this limit, or vice versa. A, , Supplement to Section 4.3, Solat Energy, Besides the distance-velocity and area problems, which we used to introduce, the integral, there are other physical problems that could be used in the same, way. Here, we consider the problem of computing solar energy and shall see, how it, too, leads naturally to the integral in terms of upper and lower sums., Consider a solar cell attached to an energy storage unit (such as a, battery) as in Fig. 4.3.10. When light shines on the solar cell, it is converted, into electrical energy which is stored in the battery (as electrical-chemical, energy) for later use., , Figure 4.3.10. The storage, unit accumulates the power, received by the solar cell., , Solar cell, , Ftirrgy .;torage unit, , We will be interested in the relation between the amount E of energy, stored and the intensity I of the sunlight. The number E can be read off a dial, on the energy storage device; I can be measured with a photographer's light, meter. (The units in which E and I are measured are unimportant for this, discussion.), Experiments show that when the solar cell is exposed to a steady source, of sunlight, the change AE in the amount of energy stored is proportional to, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 22 :

222, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , the product of the intensity I and the length At of the period of exposure., Thus, , A E = K IAt,, where K is a constant depending on the apparatus and on the units used to, measure energy, time, and intensity. (We can imagine K being told to us as a, manufacturer's specification.), The intensity I can change-for example, the sun can move behind a, cloud. If during two periods, At, and At,, the intensity is, respectively, I , and, I,, then the total change in energy is the sum of the energies stored over each, individual period. That is,, AE = K I At,, ~, , + K I , A =~ ~K ( IAt,, ~ + 12At2)., , Likewise, if there are n periods, At,, . . . , At,, during which the intensity is, I , , . . . , I, (as in Fig. 4.3.1 1(a)), the energy stored will be the sum of n terms,, , Notice that this sum is exactly K times the integral of the step function g,, where g ( t ) = I, on the interval of length At,., In practice, as the sun moves gradually behind the clouds and its, elevation in the sky changes, the intensity I of sunlight does not change by, jumps but varies continuously with t (Fig. 4.3.1 1(b)). The change in stored, , Figure 4.3.11. The intensity, of sunlight varying with, time., , energy AE can still be measured on the energy storage meter, but it can no, longer be represented as a sum in the ordinary sense. In fact, the intensity now, takes on infinitely many values, but it does not stay at a given value for any, length of time., If I = f(t), the true change in stored energy is given by the integral, , which is K times the area under the graph I = f(t). If g(t) is a step function, with g(t) < f(t), then the integral of g is less than or equal to the integral of, f(t). This is in accordance with our intuition: the less the intensity, the less the, energy stored., The passage from step functions to general functions in the definition of, the integral and the interpretation of the integral can be carried out in many, contexts; this gives integral calculus a wide range of applications., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 23 :

4.3 The Definition of the Integral, , 223, , Exercises for Section 4.3, In Exercises 1-4, draw a graph of the given step function, and compute the signed area of the region between its graph and the x axis., , Figure 4.3.12. Graphs for, Exercises 9- 12., 13. Find L 4 ( l / x ) d x to within an error of no more, than &., 14. If you used the method in Example 4 to calculate, In Exercises 5-8, compute the indicated integrals., 5. i i g ( x ) d x , g as in Exercise 1., , i 2 ( l / x ) d x to within, , @ 15. Estimate, , 1 16. Estimate, 8. r 2 g ( x ) d x . g as in Exercise 4., In Exercises 9-12, write the signed areas of the shaded, regions in terms of integrals. (See Figure 4.3.12.), , how many subintervals, , would you need?, , 6, fO,g(x)dx, g as in Exercise 2., 7, f02X(x)dx, g as in Exercise 3., , i&j,, , i2, J2, , ( l / x 2 ) d x to within, , A., , ( I / x 2 ) d x to within, , 17. A bus moves on the line with velocity given by, c = 5(r2- 51 + 6). Write a formula in terms of, integrals for:, (a) the displacement of the bus between t = 0, and r = 3;, (b) the actual disiance the bus travels between, t = 0 and t = 3., 18. A bus moves on the line with velocity given by, c = 6 r 2 - 301 + 24. Write a formula in terms of, integrals for:, ( a ) the displacement of the bus between t = 0, and t = 5;, (b) the actual distance the bus travels beiween, t = 0 and t = 5., In Exercises 19-22, write the given integral as a limit of, sums., I 9 J'x5dx., , 20. i ' 9 x 3 d x ., , 21. J 4 L d x ., 2 I+x2, , 22., , 23. Show that, 24. Show that, , -3, , ,<, , 1', , J2, , tI0dt, , I;~, , I+x, , ( t 3 - 4)dl, , <, , dx., , < 4., , 1., , 25. Let f(t) be defined by, f(t)=, , i, , 2, 0, , -1, , if, if, if, , O<t<l,, l<t<3,, 3<t<4., , For any number x in (0,4], f(t1 is a step function, on [0, x]., (a) Find ff(r)dt, , as a function of x. (You will, , need to use different forinulas on different, intervals.), , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 24 :

224, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , d, , (b) Let F(x) = Xf(t)dt, for x in (0,4]. Draw a, graph of F., (c) At which points is F differentiable? Find a, formula for F'(x)., 26. Let f be the function defined by, , *30. Suppose that f(x) is a step function on [a, b ] , and, let g(x) = f(x) + k, where k is a constant., (a) Show that g(x) is a step function., (b) Find j b g ( x ) d x in terms of bbf(x)dx., a, , *31. Let h(x) = kf(x), where f(x) is a step function, on [a,b]., (a) Show that h(x) is a step function., (b) Find I b h ( x ) dx in terms of bbf(x) dx., a, , (a) Find Jlof(x)dx., , *32. For x E [0, 11 let f(x) be the first digit after the, decimal point in the decimal expansion of x., , (b) Find J9f(x) dx., , (a) Draw a graph off. (b) Find j l f ( x ) d x ., , 2, , (c) Suppose that g is a function on [ l , 101 such, that g(x) < f(x) for all x in [ l , 101. What, , 0, , *33. Define the functions f and g on [O, 31 as follows:, , inequality can you derive for 1log(x)dx?, (d) With g(x) as in part (c), what inequalities can you obtain for, , 1;", , -, , J;, , 'O, , 2g(x)dx and, , g(x) dx? [Hint: Find functions like f, , with which you can compare 2g and -g.], 27. Let f(t) be the "greatest integer function"; that, is, f(t) is the greatest integer which is less than or, equal to t-for example, f(n) = n for any integer,, f(54)= 5, f(-54) = -6, and so on., (a) Draw a graph of f(t) on the interval - 4,4]., (b) Find, , ', , f, , b6f(t)dt, I_:/(t)dt., , and, , (a) Draw the graph of f(x), , (b) Compute, , X2, , [f(x), , + g(x) and compute, , + g(x)] dx., , (c) Compare l32/(x) dx with 2 'f(x)dx., , i,, , (d) Show that, , L4'5, , f (t) dt., , (c) Find a general formula for, n is any positive integer., (d) Let F(x) =, , i", , I", , f(t) dt, where x, , f(t)dt, where, , > 0., , Draw a, , graph of F for x E [0, 41, and find a formula, for F1(x), where it is defined., 28. A rod 1 meter long is made of 100 segments of, equal length such that the linear density of the, kth segment is 30k grams per meter. What is the, total mass of the rod?, 29. The volume of a rod of uniform shape is A Ax,, where A is the cross-sectional area and Ax is the, length., (a) Suppose that the rod consists of n pieces,, with the ith piece having cross-sectional area, A, and length Ax,. Write a formula for the, volume., (b) Suppose that the cross-sectional area is, A = f(x), where f is a function on [0, L], L, being the total length of the rod. Write a, formula for the volume of the rod, using the, integral notation., , (e) Is the following true?, , *34. Suppose that f is a continuous function on [a, b], and that f(x) # 0 for all x in [a, b]. Assume that, a # b and that f((a b)/2) = 1. Prove that, , +, , Lbf(x)dx, , > 0. [Hint: Find a lower sum.], , *35. Compute the exact value of, , I', , x5dx by using, , Riemann sums and the formula, , *36. Let the function f be defined on [0, 31 by, =, , (, , if, if, , x is a rational number,, x is irrational., , (a) Using the fact that between every two real, numbers there lie both rationals and irrationals, show that every upper sum for f on, [0, 31 is at least 6., (b) Show that every lower sum for f on [0, 31 is, at most 0., (c) Is f integrable on [0, 3]? Explain., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 25 :

4.4 The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, , 225, , 4.4 The Fundamental, Theorem of Calculus, The processes of integration and difSerentiation are inverses to one another., We now know two ways of expressing the solution of the distance-velocity, problem. Let us recall the problem and these two ways., Problem, , First Solution, , A bus moves on a straight line with given velocity v = f ( t ) for a, the displacement Ad of the bus during this time interval., , < t < b. Find, , The first solution uses antiderivatives and was presented in Section 2.5. Let, y = F ( t ) be the position of the bus at time t. Then since u = dy/dt, i.e.,, f = F ' , F is an antiderivative of f. The displacement is the final position, minus the initial position; i.e.,, Ad = F ( b ) - F ( a ) ,, ('1, the difference between the values of the antiderivative at f = a and t = b., , Second Solullon, , The second solution uses the integral as defined in the previous section. We, saw that, , Ad, , =, , I,"f ( I ) d t ., , We arrived at formulas (1) and (2) by rather different routes. I-Iowever,, the displacement must be the same in each case. Equating (1) and (2), we get, , This equality is called the fundamental theorem of calculus. It expresses the, integral in terms of an antiderivative and establishes the key link between, differentiation and integration., The argument by which we arrived at (3) was based on a physical model., Later, in this section, we shall also give a purely mathematical proof., With a slight change of notation, we restate (3) in the following box., , Suppose' that the function F is differentiable everywhere on [ a ,b ] and, that F' is integrable on [ a ,bj. Then, , In other words, i f f is integrable on [ a ,b ] and has an antiderivative F,, , We may use this theorem to find the integral which we previously computed, "by hand" (Example 6 , Section 4.2)., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 26 :

226, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , Example 1, , Using the fundamental theorem of calculus, compute, , i, , 1, , x dx., , Solution By the power rule, an antiderivative for f ( x ) = x is F ( x ) = f x2. (You could, also have found F ( x ) by guessing, and you can always check the answer by, differentiating f x2.) The fundamental theorem gives, , which agrees with our earlier result. A, Next, we use the fundamental theorem to obtain a new result., Example 2, Solution, , Using the fundamental theorem of calculus, compute i\2dx., Let f ( x ) = x 2 ; again by the power rule, we may take F ( x ) = + x 3 . By the, fundamental theorem, we have, ibx2dx=, , ib, , f(X)d~=, F ( b ) - F ( a ) = +b3- +a3., , We conclude that Jb,x2dx= l3 ( b 3 - a3). This gives the area under a segment, of the parabola y = x 2 (Fig. 4.4.1). A, We can summarize the integration method provided by the fundamental, theorem as follows:, Figure 4.4.1. The shaded, area is Jtx2dx = f ( b 3- a 31., , To integrate the function f ( x ) over the interval [ a ,b ] : find an antiderivative F ( x ) for f ( x ) , then evaluate F at a and b and subtract the results:, , Notice that the fundamental theorem does not specify which antiderivative to, use. However, if F , and F2 are two antiderivatives off on [a,b], they differ by, a constant (see Section 3.6); F,(t) = F2(t)+ C , and so, F,(b) - F , ( a ) = [ F 2 ( b )+ C] - [ F2(a)+ C] = F,(b) - F2(a)., (The C's cancel.) Thus all choices of F give the same result., Expressions of the form F(b) - F(a) occur so often that it is useful to, have a special notation for them., , Example 3, , Solution, , Find ( x 3+ 5)Ii., Here F ( x ) = x 3 + 5 and, ( x 3+ 5)Ii = F(3) - F(2), = (33, , + 5 ) - (23 + 5 ), , = 32 - 13 = 19. A, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 27 :

4.4 The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, , 227, , In terms of this new notation, we can write the formula of the fundamental, theorem of calculus in the form, , where F is an antiderivative off on [ a ,b ] ., Example 4, Solution, , Example 5, Solution, , Find f ( x 2, , + 1)dx., , By the sum and power rules for antiderivatives, and antiderivative for x 2, is f x3 X . By the fundamental theorem,, , +, , Evaluate, , 1, , 2, , +1, , 1 dx., , An antiderivative of l / x 4 = x - is~ - 1 / 3 x 3 , since, , Hence, , We will now give a complete proof of the fundamental theorem of calculus., The basic idea is as follows: letting F be an antiderivative for f on [ a ,b ] , we, will show that the number F ( b ) - F ( a ) lies between any lower and upper, sums for f on [ a ,b ] . Since f is assumed integrable, it has upper and lower sums, arbitrarily close together, and the only number with this property is the, integral off (see page 217). Thus, we will have F ( b ) - F ( a ) = f ( x ) d x ., , Jt, , Proof of the For the lower sums, we must show that any step function g below f on ( a ,b ), Fundamental has integral at most F ( b ) - F(a). So let k , , k,, . . . , k, be the values of g on, Theorem the partition intervals ( x o , x , ) , ( x , , x 2 )., . . , ( x,-,, x,) (See Fig. 4.4.2). On, , Figure 4.4.2. The integral, of g is a lower sum for J on, , ( x i - , , x i ) , ki < f ( x ) = F f ( x ) , so the difference quotient for F satisfies the, inequality k, < [ F ( x i )- F ( x i _, ) ] / [ x i- x i _ ,I, by the first consequence of the, mean value theorem (Section 3.6). Thus, k, Ax, < F(x,) - F(x,- ,). Summing, from i = 1 to n, we get, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 28 :

228, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , The lekhand side is just the integral of g on [ a ,bj, while the right-hand side is, a telescoping sum which collapses to F(x,) - F(x,); so we have proven that, J i g ( x ) d x ,< F ( b ) - F(a)., An identical argument works for upper sums: Pf h is a step function, above f on ( a ,b), then F ( b ) - F ( a ) < J i h ( x ) d x (see Exercise 49). Thus the, proof of the fundamental theorem is complete. W, Here are two more examples illustrating the use of the fundamental, theorem. Notice that any letter can be used as the variable of integration, just, like the "dummy variable" in summation., Example 6, Solution, , Find, , L4(z2+, , 3t7/')dr., , By the sum, constant multiple, and power rules for antiderivatives, an antiderivative for t 2 + 3t7/2is ( t 3 / 3 ) 3 . ( 2 / 9 ) t 9 l 2 .Thus,, , +, , In the next example, some algebraic manipulations are needed before the, integral is computed., , 9, 2, , Example 7 Compute, Solution, , I;', , ds ., , The integrand may be broken apart:, , We can find an antiderivative term by term, by the power rule:, , Next we use the fundamental theorem to solve area and distance-velocity, problems. Let us first recall, from Sections 4.2 and 4.3, the situation for areas, under graphs., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 29 :

4.4 The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, , If f(x), , > 0 for x, , 229, , in [ a ,b], the area under the graph o f f between x = a, , 1;, , Iff is negative at some points of [ a ,b], then f(x)dx is the signed, area of the region between the graph off, the x axis, and the lines x = a, , Example 8, , (a) Find the area of the region bounded by the x axis, the y axis, the line, x = 2, and the parabola y = x2. (b) Compute the area of the region shown in, Fig. 4.4.3., , Figure 4.4.3. Compute this, area., Figure 4.4.4. The shaded, area equals j i x 2 dx., , Solution, , (a) The region described is that under the graph of f(x) = x 2 on [0,2] (Fig., 4.4.4). The area of the region is Jix2dx = 'x3I2, 3, o = 83 ., (b) The region is that under the graph of y = x3 from x = 0 to x = 1, so its, area is j;x3dx. By the fundamental theorem,, , Thus, the area is, Example 9, , (a) Interpret, , 4. A, , 8', , (x2 - 1)dx in terms of areas and evaluate. (b) Find the shaded, , area in ~ i ~ u r e - 4 . 4 . 5 ., , F i m e 4.4.6. j i ( x 2 - 1) dx, is the difference between, the areas of R2 and R,., , Figwe 4.4.5. Find the area, of this region., , Solution, , (a) Refer to Fig. 4.4.6. We know that the integral represents the signed area of, the region between the graph of y = x 2 - 1 and the x axis. In other words, it is, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 30 :

230, , Chapter 4 The integral, , the area of R, minus the area of R,. Evaluating,, , (b) For functions which are negative on part of an interval, we must recall,, from Section 4.3, that the integral represents the signed area between the graph, and the x axis. To get the ordinary area, we must integrate piece by piece., The area from x = 0 to x = 1 is Jhx3dx. The negative of the area from, x = - to x = 0 is J0 , / , x 3 d x . Thus the total area is, , +, , Finally, in this section, we consider the use of the fundamental theorem to, solve displacement problems. The following box summarizes the method,, which was justified earlier in this section., , Displacements and Velocity, If a particle on the x axis has velocity 6 = f(t) and position x = F ( t ) ,, then the displacement F ( b ) - F ( a ) between the times t = a and t = b is, obtained by integrating the velocity from r = a to 1 = h :, Displacement from, time t = a to t = b, , Example 10, , Solution, , = lh(velocity)dt., , An object moving in a straight line has velocity t. = 5t4, far does the object travel between t = 1 and t = 2?, , + 3 t 2 at time t . How, , The displacement equals the total distance travelled in this case, since z; > 0., Thus, the displacement is, , Thus, the object travels 38 units of length between t, , = 1 and, , t = 2. A, , We have seen that the geometric interpretation of integrals of functions that, can sometimes be negative requires the notion of signed area. Likewise, when, velocities are negative, we have to be careful with signs. The integral is always, the displacement; to get the actual distance travelled, we must change the sign, of the integral over the periods when the velocity is negative. See Fig. 4.4.7 for, a typical situation., , Figure 4.4.7. The total, distance travelled is, j:v dt - j:v dt; the, displacement is f2v dt., , > 0 lor, , starting, , u, , posltloll, , U</<<, , /, , =u, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 31 :

4.4 The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, , Example 11, , Solution, , 231, , An object on the x axis has velocity v = 2 t - t 2 at time t . If it starts out at, t - 0 , where is it at time t = 3? How far has it travelled?, x = -1, Let x = f ( t ) be the position at time t . Then, , +, , Since f ( 0 ) = - 1 , the object is again at x = 0 f ( 0 ) = - I at time t = 3., The object turns around when v changes sign, namely, at those t where, 2 t - t 2 = 0 or t = 0 , 2 . For O < t < 2 , v > 0 , and for 2 < t < 3 , v < O . The, total distance travelled is therefore, , Exercises for Section 4.4, Using the fundamental theorem of calculus, compute, the integrals in Exercises 1-4., , L3, , du., , 24., , J4, 2, , u-1, , du., , Calculate the areas of the regions in Exercises 25-28, (Figure 4.4.8)., , 4. i 8 ( 1 + 6 ) d x ., , 3. L 6 3 x d x ., , 23., , Compute the quantities in Exercises 5-8., 5. x3I41;., 6. ( x 2 z3&)I:., 7. (3x2 + 5)l:., 8. ( x 4 + x 2 + 2)1c2., Evaluate the integrals in Exercises 9-24., , +, , +, , 9. Lbs4l3ds., , II., , 17., , 1, , ".r"', , 10. JpZl(t4 8i)dt., , dr., , 1 2 x, l2, l2 5 ,, 1, , (i+413', , 14. J-:'l, , + x2 - x3)dx., , 18. l 7 $ 3, , + z2)dz., , 2, , 19., , dt., , 2, , 21., , dx., , 22., , -1, JP2, , (x2, , +x), , 2, , dx ., , Figure 4.4.8. Regions for, Exercises 25-28., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 32 :

232, , Gkaplter 4 The Integral, , Interpret the integrals in Exercises 29 and 30 in terms of, areas, sketch, and evaluate., , 30. A 2 ( x 2- 3 ) d x ., In Exercises 31-40, find the area of the region between, the graph of each of the following functions and the x, axis on the given interval and sketch., 31. x 3 on [0,2]., 32. 1 / x 2 on [1,2]., 33. x 2 + 2 x + 3 on [I, 21., 34. x 3 + 3 x + 2 on [O,21., 35. x 4 + 2 on [ - l,l]., 36. 3x4 - 2 x 2 on [ - 1, I]., 37. x 4 + 3 x 2 + 1 ; - 2 < x < 1., 38. 8x6 + 3x4 - 2; 1 < x < 2., 39. ( I / x ~+) x ~ 1;< g 3., 40. ( 3 x + 5 ) / x 3 ; 1 < x < 2., , +, , 41. An object moving in a straight line has velocity, u = 6t4 + 3t2 at time t. How far does the object, travel between t = 1 and t = lo?, 42. An object moving in a straight line has velocity, u = 2t3 + t4 at time t. How far does the object, travel between t = 0 and t = 2?, 43. The velocity of an object on the x axis is u, = 4t - 2t2. I f it is at x = 1 at t = 0, where is it at, i = 4? Hclw far has it travelled?, , 44. The velocity of an object on the x axis is v, = t 2 - 3t + 2. If the object is at x = - 1 at t = 0,, where is it at = 2? How far has it travelled?, 45. The velocity of a stone dropped from a balloon is, 32t feet per second, where i is the time in seconds after release. How far does the stone travel, in the first 10 seconds?, 46. How far does the stone in Exercise 45 travel in, the second 10 seconds after its release? The third, 10 seconds?, *47. An object is thrown upwards from the earth's, surface with a velocity uo. (a) How far has it, travelled after it returns? (b) How far has it, travelled when its velocity is - 4uo?, *48. Suppose that F is continuous on [O,21, that F ' ( x ), < 2 for 0 $ x < f , and that F 1 ( x )< 1 whenever, f < x & 2. What can you say about the difference F(2) - F(O)?, *49. Prove that if h ( t ) is a step function on [ a ,b] such, that f ( t ) & h ( t ) for all t in the interval ( a ,b), then, h ( t )dt, where F is any antidei,, rivative for f on [a, b]., F ( b ) - F ( a ) ,<, , *50. Let ao, . . . , a, be a given set of numbers and, & = ~ , - a ~ -Let, ~ . bk=Cr=16i,dj=bi-br-l., Express the b's in terms of the a's and the d's in, terms of the 6's., , 4.5 Definite and, lndefinite Integrals, Integrals and sums have similar properties., When we studied antiderivatives in Section 2.5, we used the notation jf(x)dx, for an antiderivative off, and we called it an indefinite integral. This notation, and terminology are consistent with the fundamental theorem of calculus. We, can rewrite the fundamental theorem in terms of the indefinite integral in the, following way., , Notice that although the indefinite integral is a function involving an arbitrary, constant, the expression, , represents a well-defined number, since the constant cancels when we subtract, the value at a from the value at b., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 33 :

4.5 Definite and Indefinite Integrals, , 233, , An expression of the form j, tf(x)dx with the endpoints specified, which, we have been calling simply "an integral," is sometimes called a definite, integral to distinguish it from an indefinite integral., Note that a definite integral is a number, while an indefinite integral is a, function (determined up to an additive constant)., Remember that one may check an indefinite integral formula by differentiating., , indefinite lrrtegral Test, , +, , x)dx = F(x) C, differentiate the rightIf(, hand side and see if you get the integrand f(x)., , To check a given formula, , Example 9, Solution, , Check the formula, , J3x, , 'dx, , = x9/3, , + C., , We differentiate the right-hand side using the power rule:, , so the formula checks. A, The next example involves an integral that cannot be readily found with the, antidifferentiation rules., Example 2, , (a) Check the formula r x ( l, J, tempt to derive the formula.), (b) Find J2x(l, 0, , Solution, , + x)'dx, , = &(7x -, , 1)(1, , + x)' + C. (Do not, , at-, , + x16dx., , (a) We differentiate the right-hand side using the product rule and power of a, function rule:, d, l, 1 [7(l + x)' + (7x - 1)7(1 + x)'], - - (7x - l ) ( l, x)'] = -, , dx, , [ 56, , +, , 56, , = (1, , + x)'x., , Thus the formula checks., (b) By the fundamental theorem and the formula we just checked, we have, , 1, 2, , x(1, , + x)'dx, , 1, , = - (7x - l)(l, , 56, , + x)', , In the box on page 204 we listed five key properties of the summation process., In the following box we list the corresponding properties of the definite, integral., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 34 :

234, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , 1. i b [f(x), , 3. If a, , + g(x)] dx = i b f ( x ) d x + i b g ( x ) d x (sum rule)., , < b < c, then, , 5. If f(x), , <, , I c f ( x ) d x =Jbf(x)dx, a, +dcf(x)dx., , g(x) for all x satisfying a, , < x < b, then, , These properties hold for all functions f and g that have integrals. However,, while it is technically a bit less general, it is much easier to deduce the, properties from the antidifferentiation rules and the fundamental theorem of, calculus, assuming not only that f and g have integrals, but that they have, antiderivatives as well., Prove property 1 in the display above (assuming that f and g have antiderivatives)., , Example 3, Solullon, , Example 4, , Let F be an antiderivative for f and G be one for g. Then F, antiderivative for f g by the sum rule for antiderivatives. Thus,, , +, , +G, , is an, , Prove property 5., , Soiaati~n If f(x) < g(x) on (a, b), then ( F - G)'(x) = F'(x) - G1(x) = f(x) - g(x) < 0, for x in (a, b). Since a function with a negative derivative is decreasing, we get, , [ F ( b ) - ~ ( b )-][ ~ ( a -) G(a)] 0,, and so F(b) - F(a) < G(6) - G(a). By the fundamental theorem of calculus,, the last inequality can be written, , as required. A, Properties 2 and 3 can be proved in a yay similar to property 1. Note that, property 4 is obvious, since we know how to compute areas of rectangles., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 35 :

4.5 Definite and Indefinite integrals, , 235, , Example 5, , Explain property 3 in terms of (a) areas (assume that f is a positive function), and (b) distances and velocities., , Solution, , (a) Since r f ( x ) d x is the area under the graph of f from x = a to x = c,, property 3 merely states that the sum of the areas of regions A and B in Fig., 4.5.1 is the total area., , Figure 4.5.1. Illustrating, , the rule j:f(x) dx =, I:fcx> dx + Jif(x)dx., (b) Property 3 states that the displacement for a moving object between times, a and c equals the sum of the displacements between a and b and between b, and c. A, We have defined the integral J?(x)dx when a is less than b ; however, the, right-hand side of the equation, , makes sense even when a > h. Can we define j'tf(x)d.u for the case a, that this equation will still be true? The answer is simple:, !f b < a and f is iniegvahle on [ b . a ] , we dejine, , 6 , K ' e define jtf(x)d,u to he zero., Notice that if F' is integrable on [ / > . ( I ] , where h, preceding definition and the fundamental theorem., , !fa, , b so, , =, , < a., , then by the, , so the equation j ! : ~ ' ( x ) d x= F ( b ) - F ( a ) is still valid., , Example 6, , Find d 2 x ' d x ., , Solution j i x 3 d x = (x4/4)12 = i ( 1 6 - 1296) = -320. (Although the function f ( x ) = x', is positive, the integral is negative. To explain this, we remark that as x goes, from 6 to 2, " d x is negative.") A, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 36 :

238, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , We have seen that the fundamental theorem of calculus enables us to compute, integrals by using antiderivatives. The relationship between integration and, differentiation is completed by an alternative version of the fundamental, theorem. Let us first state and prove it; its geometric meaning will be given, shortly., , Iff is continuous on [a,%], then, , We now justify the alternative version of the fundamental theorem. In, Exercises 49-53, it is shown that f has an antiderivative F. Let us accept this, fact here., The fundamental theorem applied to f on the interval [a, x] gives, , Differentiating both sides,, , d, dx, , = - F(x), , (since F(a) is constant), , =f(x>, , (since F is an antiderivative off j., , Thus the alternative version is proved., Notice that in the statement of the theorem we have changed the, (dummy) variable of integration to the letter "s" to avoid confusion with the, endpoint "x.", Example 7, Solution, , Verify the formula, , A, dx, , b, , xf(s)ds, , = f(x), , for f(x) = x., , The integral in question is, , (Ix, , f (s) ds, dx 0, so the formula holds. A, , Thus,, , Example 8, , Let F(x) =, , ds. Find F'(3)., jX, 1+s2+s3, 2, , Solullon, , Using the alternative version of the fundamental theorem, with f(s) =, 1/(I + s2+ s3), we have Fr(3) = f(3) = 1/(1 + 3' 33) = $. Notice that we, did not need to differentiate or integrate 1/(1 + s2 s3) to get the answer. A, , +, +, , At the top of the next page, we summarize the two forms of the fundamental, theorem., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 37 :

4.5 Definite and indefinite Integrals, , 237, , Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, Usual Version:, , ib, , F 1 ( x )dx, , =, , F(b) - F(a)., , Integrating the derivative of F gives the change in F., , A LXfw, , Alternative Version: -, , ds, , =f(x)., , Differentiating the integral off with respect to the upper limit gives f., , The alternative form of the fundamental theorem of calculus has an illuminating interpretation and explanation in terms of areas. Suppose that f ( x ) is, non-negative on [ a ,b]. Imagine uncovering the graph off by moving a screen, to the right, as in Fig. 4.5.2. When the screen is at x , the exposed area is, , A = ~ , f ( s ) d sThe, ., alternative eersion of the fundamental theorem can be, phrased as follows: as the screen moves to the right, the rate of change of, exposed area A with respect to x , d A / d x , equals f ( x ) . This same conclusion, can be seen graphically by investigating the difference quotient,, A ( x Ax) - A ( x ), Ax, The quantity A ( x Ax) - A ( x ) is the area under the graph of f between x, and x Ax. For Ax small, this area is approximately the area of the rectangle, , +, , +, , +, , Figure 4.5.3. The geometry, needed to explain why, d A / d x = f(x)., , with base Ax and height f ( x ) , as in Fig. 4.5.3. Therefore,, , and the approximation gets better as Ax becomes smaller. Thus, A(x, , + Ax) - A ( x ), , Ax, approaches f ( x ) as Ax +O, which means that d A / d x = f(x). I f f is continu-, , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 38 :

238, , Chapter 4 The Integral, , ous, this argument is the basis for a rigorous proof of the alternative version of, the fundamental theorem. See Exercises 49-53 for additional details., , Exercises Isr Section 4.5, In Exercises 1-4, check the integration formula by, differentiating the right-hand side., 1. 5 x 4 d x = x 5 + C., , i, , 19. Explain property 2 of integration in terms of (a), areas and (b) distances and velocities., 20. Explain property 5 of integration in terms of, (a) areas and (b) distances and velocities., ~f i ' f ( x ) d x = 3. i 2 f ( x ) dx = 4. and, , 6', , f(x)dx, , =, , -8., , calculate the quantities in Exercises 21-24, using the, properties of integration., , 5. (a) Check the following integral, Calculate the integrals in Exercises 25-28., ( b ) Evaluate, , i', , dl., , 3t2, , 6. ( a ) Check the following integration forniula:, , 27., , 1:, , dx., , Verify the formula, , ( b ) Evaluate, , 6', , [ ( s S +2s, , + 1)/(1, , 7. ( a ) Calculate the derivative of, I, , ( b ) Find, , ( 3 x 2 + .r4), , + x?)?, , (I, , 8. ( a ) Differentiate, ( b ) Find, , /*-( I, 3, , I, , + .r, , -, , .~)~]clr., , -, , x- l, , dx., , 'f(s)d.s = f ( x ) for the func-, , tions in Exercises 29 and 30., 29. /(.Y) = .u3 - 1 ., 30. /(.u) = u", .u2 + .u., 1, 31. Let F(r)=, , ( 4 - ,s)>, , i', , /_12, , + 8j3, , ds. Find F'(4)., , Y', -, , s 2 +I, , c1.r, and, , 28., , Evaluate the derivatives in Exercises 33-36., 3, d.r ., , 1, , + .r, , -, , I, , du in two ways., +x)', , Calculate the definite integrals in Exercises 9-18, , 37. Let c ( t ) be the velocity of a moving object. In, this context, interpret the formula, , 38. Interpret the alternative version of the fundamental theorem of calculus in the context of the, solar energy exaniple in the Supplement to Section 4.3., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 39 :

4.5 Definite and Indefinite Integrals, , 239, , 39. Suppose that, , :, :14+s2, &!, - . What is F1(x)?, , *45. Let F(x) =, , JX2, , s46. Calculate (a) Draw a graph off on the interval [O, 61., , s47. Find a formula for d, , (b) Find 16f(t)dt., , and explain, , 0, , your formula in terms of areas., , (c) Find b6f(x)dx., (d) Let F(t) = j b f(s)ds. Find the formula for, F(t) in [0,6] and draw a graph of F., (e) Find F1(t) for t in (0,6)., 40. (a) Give a formula for a function f whose graph, is the broken line segment ABCD in Fig., 4.5.4., (b) Find, , i f (t) dt ., lo, , 3, , (c) Find the area of quadrilateral ABCD by, means of geometry and compare the result, with the integral in part (b)., , 41. Let f be continuous on the interval I and let a ,, and a, be in I. Define the functions:, ), , I, , continuous on [a, b], then F(t) = ff(s) ds is an antiderivative off., *49. Prove property 3 for an integrable function f;, that is, if f is integrable on [a, b] and on [b, c],, then f is integrable on [a, c] and, , [Hint: Let I be the right-hand side. Show that, every number less than I is a lower sum for f on, [a, c] and, likewise, every number greater than I, is an upper sum. If S < I, show by a general fact, about inequalities that you can write S = SI, S,, where S , < j:f(x)dx and S2 < jZf(x)dx., Now piece together a lower sum corresponding, to S l with one for S,.], ~ 5 0 Prove, ., property 5 for integrable functions f and g., [Hint: Every lower sum for f is also one for g.], *51. Show that, , +, , Figure 4.5.4. Find a, formula for f., , F, , jr, , d, x, *48. Compute ds, I + X dx, ~., Exercises 49-53 outline a proof of this fact: if f is, , =f, , )d, aI, , and, , F,(t), , =, , itf(s) ds., "2, , (a) Show that Fl and F2 differ by a constant., (b) Express the constant F2- FI as an integral., 42. Develop a formula for j x ( l + x)" dx for n # - 1, or -2 by studying Example 2 [Hint: Guess the, answer (ax + b)(l + x)"+' and determine what a, and b have to be.], *43. (a) Combine the alternative version of the fundamental theorem of calculus with the chain, rule to prove that, , (b) Interpret (a) in terms of Fig. 4.5.5., , using property 3 of the integral., *52. Show that (I/h)J:+hf(s)ds lies between the maximum and minimum values of f on the interval, [t, t + h] (you may assume h > 0; a similar argument is needed for h < 0). Conclude that, , for some c between t and t + h, by the intermediate value theorem. (This result is sometimes, called the mean value theorem for integrals; we, will treat it again in Section 9.3.), *53. Use continuity off and the results from Exercises, 51 and 52 to show that F' = f., s54. Exercises 49-53 outlined a complete proof of the, alternative version of the fundamental theorem, of calculus. Use the "alternative version" to, prove the "main version" in Section 4.4., , Assume L L t f'=f, , wa%*anuaa~., , Figure 4.5.5. The rate of change of the exposed area, with respect to t is f(g(t)). g'(t)., , Copyright 1985 Springer-Verlag. All rights reserved.

Page 40 :