Page 1 :

984, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , 12.1, , Vector-Valued Functions and Space Curves, In Section 10.2 we saw that the position of an object such as a boat or a car moving, in the xy-plane can be described by a pair of parametric equations, x � f(t), , y � t(t), , where f and t are continuous functions on a parameter interval I., Using vector notation, we can denote the position of the object in an equivalent, and somewhat abbreviated form via its position vector r as follows: For each t in, I, the position vector r of the object is the vector with initial point at the origin and, terminal point ( f(t), t(t)). In other words,, r(t) � 具 f(t), t(t)典 � f(t)i � t(t)j, , t僆I, , As t takes on increasing values, the terminal point of r(t) traces the path of the object, which is a plane curve C. This is illustrated in Figure 1 for the parameter interval, I � [a, b]., y, C, , ( f(a), g(a)), , ( f(t), g(t)), ( f(b), g(b)), , FIGURE 1, As t increases from a to b, the terminal, point of r traces the curve C., , [, a, , t, , ], b, , r(a), , t, , r(t), , r(b), x, , 0, , Parameter interval [a, b], , Similarly, in 3-space we can describe the position of an object such as a plane or, a satellite using the parametric equations, x � f(t), , y � t(t), , z � h(t), , where f, t, and h are continuous functions on a parameter interval I. Equivalently, we, can describe its position using the position vector r defined by, r(t) � 具 f(t), t(t), h(t)典 � f(t)i � t(t)j � h(t)k, , t僆I, , As t takes on increasing values, the terminal point of r(t) traces the path of the object,, which is a space curve C. (See Figure 2.), z, ( f(t), g(t), h(t)), C, ( f(a), g(a), h(a)), , FIGURE 2, As t increases from a to b, the terminal, point of r traces the curve C., , [, a, , t, , ], b, , r(t), , r(a), t, , 0, , ( f(b), g(b), h(b)), r(b), y, , Parameter interval [a, b], x, , The function r is called a vector-valued function, or vector function, of a real, variable t because its value r(t) is a vector and its domain (parameter interval) is a, subset of the real numbers.

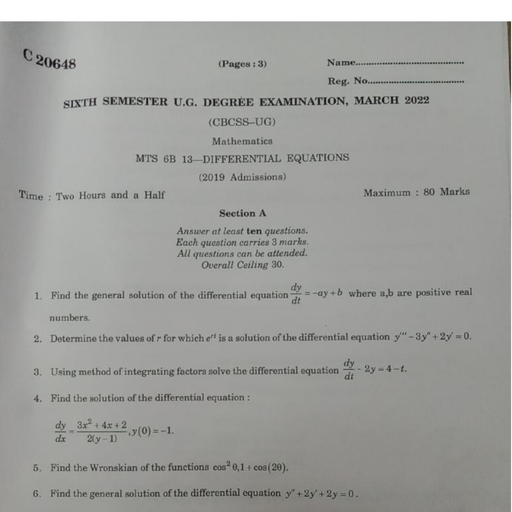

Page 2 :

12.1, , Vector-Valued Functions and Space Curves, , 985, , DEFINITION Vector Function, A vector-valued function, or vector function, is a function r defined by, r(t) � f(t)i � t(t)j � h(t)k, where the component functions f, t, and h of r are real-valued functions of the, parameter t lying in a parameter interval I., , Unless otherwise specified, the parameter interval will be taken to be the intersection of the domains of the real-valued functions f, t, and h., , EXAMPLE 1 Find the domain (parameter interval) of the vector function, 1, r(t) � h , 1t � 1, ln ti, t, Solution The component functions of r are f(t) � 1>t, t(t) � 1t � 1, and, h(t) � ln t. Observe that f is defined for all values of t except t � 0, t is defined for, all t � 1, and h is defined for all t � 0. Therefore, f, t, and h are all defined if t � 1,, and we conclude that the domain of r is [1, ⬁)., , Curves Defined by Vector Functions, As was mentioned earlier, a plane or space curve is the curve traced out by the terminal point of r(t) of a vector function r as t takes on all values in a parameter interval., , EXAMPLE 2 Sketch the curve defined by the vector function, r(t) � 具3 cos t, �2 sin t典, Solution, , 0 � t � 2p, , The parametric equations for the curve are, x � 3 cos t, , and, , y � �2 sin t, , Solving the first equation for cos t and the second equation for sin t and using the identity cos2 t � sin2 t � 1, we obtain the rectangular equation, y2, x2, �, �1, 9, 4, The curve described by this equation is the ellipse shown in Figure 3. As t increases, from 0 to 2p, the terminal point of r traces the ellipse in a clockwise direction., y, 2, , (t � 3π2 ), (3 cos t, �2 sin t), , FIGURE 3, As t increases from 0 to 2p, the, terminal point of the vector r(t) traces, y2, x2, the ellipse, �, � 1 in a clockwise, 9, 4, direction, starting and ending at (3, 0)., , (t � π), �3, [, 0, , ], 2π, , r(t), 0, , t, , Parameter interval [0, 2π], , �2, , (t � 0, 2π), x, , 3, , (t � π2 )

Page 3 :

986, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , EXAMPLE 3 Sketch the curve defined by the vector function, r(t) � (2 � 4t)i � (�1 � 3t)j � (3 � 2t)k, Solution, , 0�t�1, , The parametric equations for the curve are, x � 2 � 4t, , y � �1 � 3t, , z � 3 � 2t, , which are parametric equations of the line passing through the point (2, �1, 3) with, direction numbers �4, 3, and 2. Because the parameter interval is the closed interval, [0, 1], we see that the curve is a straight line segment: Its initial point (2, �1, 3) is the, terminal point of the vector r(0) � 2i � j � 3k, and its terminal point (�2, 2, 5) is, the terminal point of the vector r(1) � �2i � 2j � 5k. (See Figure 4.), z, , (�2, 2, 5), C, , 5, , r(1), (2, �1, 3), , r(t), r(0), , FIGURE 4, As t increases from 0 to 1, the tip of, r(t) traces the straight line segment, from (2, �1, 3) to (�2, 2, 5)., , z, , [, 0, , ], 1, , 1 1, 2, , t, , Parameter interval [0, 1], , 2, , 3, , 3, , y, , x, , EXAMPLE 4 Sketch the curve defined by the vector function, r(t) � 3i � tj � (4 � t 2)k, , 4, , Solution, , r(t), , �2 � t � 2, , The parametric equations for the curve are, x�3, , y�t, , z � 4 � t2, , Eliminating t from the second and third equations, we obtain, 2, (3, �2, 0), x, , 3, , (3, 2, 0), , FIGURE 5, As t increases from �2 to 2, the terminal point of r(t) traces the part of the, parabola lying in the plane x � 3 from, the point (3, �2, 0) to the point, (3, 2, 0)., , z � 4 � y2, , y, , Since the x-coordinate of any point on the curve must always be 3, as implied by the, equation x � 3, we conclude that the desired curve is contained in the parabola, z � 4 � y 2, which lies in the plane x � 3. In fact, as t runs from �2 to 2, the terminal point of r traces the part of the parabola starting at the point (3, �2, 0) [since, r(�2) � 3i � 2j] and ending at the point (3, 2, 0) [since r(2) � 3i � 2j], as shown, in Figure 5., , EXAMPLE 5 Sketch the curve defined by the vector function, r(t) � 2 cos ti � 2 sin tj � tk, Solution, , 0 � t � 2p, , The parametric equations for the curve are, x � 2 cos t, , y � 2 sin t, , z�t

Page 4 :

12.1, z, , From the first two equations we obtain, y 2, x 2, a b � a b � cos2 t � sin2 t � 1, 2, 2, , (2, 0, 2π), (t � 2π), , r(t), , x, , 987, , Vector-Valued Functions and Space Curves, , (0, 2, π_2 ), y, , (2, 0, 0), (t � 0), , FIGURE 6, As t increases from 0 to 2p, the, terminal point of r(t) traces the, helix beginning at (2, 0, 0) and, terminating at (2, 0, 2p) ., , x 2 � y2 � 4, , or, , This says that the curve lies on the right circular cylinder of radius 2, whose axis is, the z-axis. At t � 0, r(0) � 2i, and this gives (2, 0, 0) as the starting point of the curve., Since z � t, the z-coordinate of the point on the curve increases (linearly) as t increases,, and the curve spirals upward around the cylinder in a counterclockwise direction,, terminating at the point (2, 0, 2p) [r(2p) � 2i � 2pk]. The curve, called a helix, is, shown in Figure 6., , EXAMPLE 6 Find a vector function that describes the curve of intersection of the, cylinder x 2 � y 2 � 4 and the plane x � y � 2z � 4. (See Figure 7.), z, , z, , 4, , 4, x2 � y2 � 4, C, , x � y � 2z � 4, , 4, , 4, , y, , x, , FIGURE 7, , 4, , 4, , y, , x, , (a) Intersection of the plane and the cylinder, , (b) Curve of intersection, , Solution If P(x, y, z) is any point on the curve of intersection C, then the x- and, y-coordinates lie on the right circular cylinder of radius 2 and axis lying along the, z-axis. Therefore,, x � 2 cos t, , and, , y � 2 sin t, , To find the z-coordinate of the point, we substitute these values of x and y into the, equation of the plane, obtaining, 2 cos t � 2 sin t � 2z � 4, , or, , z � 2 � cos t � sin t, , So a required vector function is, r(t) � 2 cos ti � 2 sin tj � (2 � cos t � sin t)k, , 0 � t � 2p, , You might have noticed that the space curves in Examples 4, 5, and 6 are relatively, easy to sketch by hand. This is partly because they are relatively simple and partly, because they lie in a plane. For more complicated curves we turn to computers., , EXAMPLE 7 Use a computer to plot the curve represented by, r(t) � (0.2 sin 20t � 0.8) cos ti � (0.2 sin 20t � 0.8) sin tj � 0.2 cos 20tk, 0 � t � 2p

Page 5 :

988, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , Solution, , The curve is shown in Figure 8., 1.0, 0.5, 0.0, , z, , �0.5, �1.0, 0.2, 0.0, , x, , �0.2, �1.0, , FIGURE 8, The curve in Example 7 is, called a toroidal spiral, because it lies on a torus., , �0.5, , 0.0, y, , 0.5, , 1.0, , Limits and Continuity, Because the range of the vector function r is a subset of vectors in two- or threedimensional space, the properties of vectors given in Chapter 11 can be used to study, the properties of vector functions. For example, we add two vector functions componentwise. Thus, if, r1(t) � f1(t)i � t1(t)j � h 1(t)k, , and, , r2(t) � f2 (t)i � t2(t)j � h 2(t)k, , then, (r1 � r2)(t) � r1(t) � r2(t) � [ f1 (t) � f2 (t)]i � [t1(t) � t2(t)]j � [h 1(t) � h 2 (t)]k, Similarly, if c is a scalar, then the scalar multiple of r by c is, (cr)(t) � cr(t) � cf(t)i � ct(t)j � ch(t)k, Next, because the components f, t, and h of the vector function r are real-valued, functions, we can investigate the notions of limits and continuity involving r using the, properties of such functions. As you might expect, the limit of r(t) is defined in terms, of the limits of its component functions., , DEFINITION The Limit of a Vector Function, Let r be a function defined by r(t) � f(t)i � t(t)j � h(t)k. Then, lim r(t) � C lim f(t)D i � C lim t(t)D j � C lim h(t)D k, t→a, , t→a, , t→a, , t→a, , provided that the limits of the component functions exist., , To obtain a geometric interpretation of lim t→a r(t) , suppose that the limit exists., Let lim t→a f(t) � L 1, lim t→a t(t) � L 2, and lim t→a h(t) � L 3, and let L � L 1i � L 2 j �, L 3k. Then, by definition, lim t→a r(t) � L. This says that as t approaches a, the vector, r(t) approaches the constant vector L. (See Figure 9.)

Page 6 :

12.1, , Vector-Valued Functions and Space Curves, , 989, , z, , Historical Biography, Hulton Archive/Getty Images, , r(t), 0, [, t, , ], a, , t, , y, , Parameter interval, , JOSIAH WILLARD GIBBS, (1839–1903), Josiah Willard Gibbs, an American mathematician and physicist, did not attain the, level of fame that his European contemporaries enjoyed until his work was translated into German in 1891. He made many, contributions to the study of vector analysis, thermodynamics, and electromagnetics, and provided a firm mathematical foundation for statistical mechanics. Because of, the depth and application of his work,, Albert Einstein referred to Gibbs as “the, greatest mind in American history.” Gibbs’s, mother was an amateur ornithologist, and, his father was a professor of sacred literature at Yale. Gibbs, who began school at, the age of 9, eventually attended Yale himself. He earned a bachelor’s degree at the, age of 19 and showed promise that he, would follow his father into the area of, philology. At the time, the American academy awarded doctorates in only applied, science and mathematics, yet Gibbs’s doctoral thesis was written on spur gear, design. As a result of this thesis, he was, awarded the first doctorate of engineering, in the United States. In 1866 he embarked, on a three-year trip abroad, where he, attended lectures in physics at many European universities. Upon his return to the, United States, Gibbs was appointed to a, position of professor of mathematical, physics at Yale. He presented his first work, of vector analysis while teaching there., Gibbs’s courses included the first collegelevel vector analysis course. Using Gibbs’s, class notes, Edwin Wilson wrote a textbook,, published in 1901, that was titled Gibbs’, Vector Analysis. This textbook reached a, wider audience than Gibbs’s own publications did, and it led to Gibbs receiving, many awards, including honorary doctor of, science degrees from Erlangen, Williams, College, and Princeton University., , L, , x, , FIGURE 9, lim t→a r(t) � L means that as t approaches a, r(t) approaches L., , EXAMPLE 8 Find lim t→0 r(t), where r(t) � 1t � 2i � t cos 2tj � e�t k., Solution, , lim r(t) � C lim 1t � 2 D i � C lim t cos 2tD j � C lim e�tD k, t→0, , t→0, , t→0, , t→0, , � 12i � k, The notion of continuity is extended to vector functions via the following definition., , DEFINITION Continuity of a Vector Function, A vector function r is continuous at a if, lim r(t) � r(a), t→a, , A vector function r is continuous on an interval I if it is continuous at every, number in I., , It follows from this definition that a vector function is continuous at a if and only, if each of its component functions is continuous at a., , EXAMPLE 9 Find the interval(s) on which the vector function r defined by, r(t) � 1ti � a, , 1, t �1, 2, , bj � ln tk, , is continuous., Solution The component functions of r are f(t) � 1t, t(t) � 1>(t 2 � 1), and, h(t) � ln t. Observe that f is continuous for t � 0, t is continuous for all values of t, except t � �1, and h is continuous for t � 0. Therefore, r is continuous on the intervals (0, 1) and (1, ⬁).

Page 7 :

990, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , 12.1, , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, 3. a. What does it mean for a vector function r(t) to be continuous at a? Continuous on an interval I ?, b. Give an example of a function r(t) that is defined on the, interval (�1, 1) but fails to be continuous at 0., , 1. a. What is a vector-valued function?, b. Give an example of a vector function. What is the, parameter interval of the function that you picked?, 2. Let r(t) be a vector function defined by, r(t) � 具 f(t), t(t), h(t)典., a. Define lim t→a r(t)., b. Give an example of a vector function r(t) such that, lim t→1 r(t) does not exist., , 12.1, , EXERCISES, , In Exercises 1–6, find the domain of the vector function., 1. r(t) � ti �, , (c), , 1, j, t, , (d), z, , z, , 2. r(t) � cos ti � 2 sin tj � 1t � 1 k, 3. r(t) � h 1t,, , 4. r(t) � h, , 1, , ln ti, t�1, , 1, , e�t i, 1t � 1, , 5. r(t) � ln ti � cosh tj � tanh tk, 3, 6. r(t) � 1t i � e1>tj �, , 0, y, , 1, k, t�2, , 0, x, , y, x, (e), , In Exercises 7–12, match the vector functions with the curves, labeled (a)–(f). Explain your choices., , (f ), z, , 7. r(t) � t 2 i � t 2j � t 2 k, , z, , 8. r(t) � 2 cos 2ti � tj � 2 sin 2tk, 9. r(t) � ti � tj � a, , 1, t �1, 2, , bk, , 10. r(t) � t sin ti � t cos tj � tk, 0 � t � 10p, 11. r(t) � 2 cos ti � 3 sin tj � e0.1t k,, , 0, , t�0, , 0, , 12. r(t) � cos ti � sin tj � sin 3tk, (b), , (a), z, , y, , x, , y, x, z, , In Exercises 13–26, sketch the curve with the given vector function, and indicate the orientation of the curve., 13. r(t) � 2ti � (3t � 1)j,, , �1 � t � 2, , 14. r(t) � 1t i � (4 � t)j,, , t�0, , 15. r(t) � 具t , t 典,, 2, , 3, , �1 � t � 2, , 16. r(t) � 2 sin ti � 3 cos tj,, 17. r(t) � e i � e j,, t, , 0, y, , 0, y, x, x, , 2t, , �⬁, , 0 � t � 2p, t, , ⬁, , 18. r(t) � 具1 � 2 cos t, 3 � 2 sin t典,, , 0 � t � 2p, , 19. r(t) � (1 � t)i � (2 � t)j � (3 � 2t)k,, , �⬁, , t, , 20. r(t) � (2 � t)i � (3 � 2t)j � (2 � 4t)k, 0 � t � 1, 21. r(t) � 具t, t 2, t 3典,, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login., , t�0, , ⬁

Page 8 :

12.1, 22. r(t) � 2 cos ti � 4 sin tj � 3k,, , 0 � t � 2p, , 23. r(t) � 2 cos ti � 4 sin tj � tk,, , 0 � t � 2p, , 24. r(t) � ti � 2tj � sin 2tk,, , �⬁, , 25. r(t) � 具t cos t, t sin t, t典, �⬁, , 42. lim c a, , ⬁, , t, , t→�⬁, , Hint: Show that it lies on a cone., , 26. r(t) � et cos ti � et sin tj � et k,, , �⬁, , t, , ⬁, , cas In Exercises 27–30 use a computer to graph the curve described, , by the function., , t�1, bi � e2t j � tan�1 tkd, 2t � 1, , In Exercises 43–48 find the interval(s) on which the vector function is continuous., 43. r(t) � 1t � 1 i �, , 1, j, t, , 27. r(t) � 2 sin pti � 3 cos ptj � 0.1tk, 0 � t � 10, , 44. r(t) � sin ti � cos tj � tan�1 tk, , 28. r(t) � (t 2 � t � 1)i � (t 2 � 1)j � t 3k,, , 45. r(t) � h, , cos t � 1, 1t, ,, , te�1>t i, t, 1 � 2t, , 46. r(t) � a, , t2 � 4, , 29. r(t) � sin 3t cos ti � sin 3t sin tj �, , �3 � t � 3, , t, k,, 2p, , �2p � t � 2p, , (rotating sine wave), 1, 1, t2, sin ti � cos tj �, k,, 2, 2, 100p2, (Fresnel integral spiral), , 30. r(t) �, , 991, , 1 2t 2, 41. lim h e�t, , 2, i, t→⬁, t t �1, , ⬁, , t, , Vector-Valued Functions and Space Curves, , 0 � t � 10p, , 31. a. Show that the curve, , � 21 � 0.09 cos2 10t sin tj � 0.3 cos 10tk, lies on a sphere., b. Graph the curve described by r(t) for 0 � t � 2p., 32. a. Show that the curve, r(t) � (1 � cos 12t) cos ti � (1 � cos 12t) sin tj, � (1 � cos 12t)k, lies on a cone., b. Graph the curve described by r(t) for 0 � t � 2p., In Exercises 33–36, find a vector function describing the curve, of intersection of the two surfaces., 33. The cylinder x 2 � y 2 � 1 and the plane x � y � 2z � 1, , 3, bi � sin�1 tj � 1, tk, , 47. r(t) � e�t i � cos 14 � t j �, 48. r(t) �, , r(t) � 21 � 0.09 cos2 10t cos ti, , 2t, , 1, t2 � 1, , k, , 1, i � tan tj � e�t cos tk, 1t, , 49. Trajectory of a Plane An airplane is circling an airport in a, holding pattern. Suppose that the airport is located at the, origin of a three-dimensional coordinate system and that, the trajectory of the plane traveling at a constant speed is, described by, r(t) � 44,000 cos 60ti � 44,000 sin 60tj � 10,000k, where the distance is measured in feet and the time is, measured in hours. What is the distance covered by the, plane over a 2-min period?, 50. Temperature at a Point Suppose that the temperature at a, point (x, y, z) in 3-space is T(x, y, z) � x 2 � 2y 2 � 3z 2, and that the position of a particle at time t is described, by r(t) � 具t, t 2, et典. What is the temperature at the point, occupied by the particle when t � 1?, , 35. The cone z � 2x 2 � y 2 and the plane x � y � z � 1, , In Exercises 51–54, suppose that u and v are vector functions, such that lim t→a u(t) and lim t→a v(t) exist and c is a constant., Prove the given property., , 36. The paraboloid z � x 2 � y 2 and the sphere x 2 � y 2 � z 2 � 1, , 51. lim [u(t) � v(t)] � lim u(t) � lim v(t), , In Exercises 37–42, find the given limit., , 52. lim cu(t) � c lim u(t), , 34. The cylinder x 2 � y 2 � 4 and the surface z � xy, , 37. lim [(t � 1)i � cos tj � 3k], 2, , t→0, , 39. lim c 1t i � a, , t2 � 4, t, bkd, bj � a 2, t�2, t �1, , 40. lim� ccos ti �, , tan t, j � t ln tkd, t, , t→0, , t→a, , t→a, , t→a, , t→a, , 53. lim [u(t) ⴢ v(t)] � lim u(t) ⴢ lim v(t), t→a, , sin t, , cos ti, 38. lim he�t,, t→0, t, t→2, , t→a, , 54. lim [u(t), t→a, , t→a, , v(t)] � lim u(t), t→a, , t→a, , lim v(t), , t→a, , 55. a. Prove that if r is a vector function that is continuous at, a, then 冟 r 冟 is also continuous at a., b. Show that the converse is false by exhibiting a vector, function r such that 冟 r 冟 is continuous at a but r is not, continuous at a.

Page 9 :

992, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, In Exercises 59–62, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why. If it is false, explain why or give, an example to show that it is false., , 56. Evaluate, lim h, , h→0, , (t � h) � t cos(t � h) � cos t e, ,, ,, h, h, 2, , 2, , �e, i, h, , t�h, , t, , 59. The curve defined by r1(t) � t 2 i � t 2j � t 2 k is the same as, the curve defined by r2(u) � ui � uj � uk., , 57. Evaluate, lim c, t→0, , 60. If f, t, and h are linear functions of t for t in (�⬁, ⬁), then, r(t) � f(t)i � t(t)j � h(t)k defines a line in 3-space., , ln(1 � t 2), 1 � cos t, sin t, i�, j�, kd, 2, t, t, cos t � e�t, , 61. The curve defined by r(t) � f(t)i � t(t)j � ck, where c is a, constant, is a curve lying in the plane z � c., , 58. a. Find a vector function describing the curve of intersection of the plane x � y � 2z � 2 and the paraboloid, z � x 2 � y 2., b. Find the point(s) on the curve of part (a) that are closest, to and farthest from the origin., , 12.2, , 62. If r is continuous on an interval I and if a is any number in, I, then lim t→a r(t) � r(a)., , Differentiation and Integration of Vector-Valued Functions, The Derivative of a Vector Function, The derivative of a vector function is defined in much the same way as the derivative, of a real-valued function of a real variable., , DEFINITION Derivative of a Vector Function, The derivative of a vector function r is the vector function r¿ defined by, r¿(t) �, , r(t � h) � r(t), dr, � lim, dt, h→0, h, , provided that the limit exists., , To obtain a geometric interpretation of this derivative, let r be a vector function,, and let C be the curve traced by the tip of r. Let t be a fixed but otherwise arbitrary, number in the parameter interval I. If h � 0, then the vector r(t � h) � r(t) lies on, the secant line passing through the points P and Q, the terminal points of the vectors, r(t) and r(t � h), respectively. (See Figure 1.), z, , z, r (t), , r(t � h) � r(t), , P, r(t), , P, Q, , Q, , r(t � h) � r(t), h, , r(t � h), t, , t�h, , Parameter interval, , 0, , t, x, (a), , C, y, , 0, x, , C, y, , (b), , FIGURE 1, r(t � h) � r(t), As h approaches 0, Q approaches P along C, and the vector, approaches the tangent vector r¿(t)., h

Page 10 :

12.2, , Differentiation and Integration of Vector-Valued Functions, , 993, , The vector [r(t � h) � r(t)]>h, which is a scalar multiple of r(t � h) � r(t), also, lies on the secant line. (See Figure 1b.) As h approaches 0, the number t � h approaches, t along the parameter interval, and the point Q, in turn, approaches the point P along, the curve C. As a consequence, the vector [r(t � h) � r(t)]>h approaches the fixed, vector r¿(t), which lies on the tangent line to the curve at P. In other words, the derivative r¿ of the vector r may be interpreted as the tangent vector to the curve defined, by r at the point P, provided that r¿(t) 0. If we divide r¿(t) by its length, we obtain, the unit tangent vector, T(t) �, , r¿(t), 冟 r¿(t) 冟, , which has unit length and the direction of r¿., The following theorem tells us that the derivative r¿ of a vector function can be, found by differentiating the components of r., , THEOREM 1 Differentiation of Vector Functions, Let r(t) � f(t)i � t(t)j � h(t)k, where f, t, and h are differentiable functions of, t. Then, r¿(t) � f ¿(t)i � t¿(t)j � h¿(t)k, , PROOF We compute, r(t � ⌬t) � r(t), ⌬t→0, ⌬t, , We use ⌬t instead of h so as not to confuse the increment, of t with the component function h., , r¿(t) � lim, , � lim c, , f(t � ⌬t)i � t(t � ⌬t)j � h(t � ⌬t)k � [f(t)i � t(t)j � h(t)k], , � lim c, , t(t � ⌬t) � t(t), f(t � ⌬t) � f(t), h(t � ⌬t) � h(t), i�, j�, kd, ⌬t, ⌬t, ⌬t, , ⌬t, , ⌬t→0, , ⌬t→0, , d, , t(t � ⌬t) � t(t), f(t � ⌬t) � f(t), h(t � ⌬t) � h(t), di � c lim, d j � c lim, dk, ⌬t→0, ⌬t, ⌬t→0, ⌬t, ⌬t→0, ⌬t, , � c lim, , � f ¿(t)i � t¿(t)j � h¿(t)k, , EXAMPLE 1, a. Find the derivative of r(t) � (t 2 � 1)i � e�t j � sin 2tk., b. Find the point of tangency and the unit tangent vector at the point on the curve, corresponding to t � 0., Solution, a. Using Theorem 1, we obtain, r¿(t) � 2ti � e�t j � 2 cos 2tk, b. Since r(0) � i � j, we see that the point of tangency is (1, 1, 0). Next, since, r¿(0) � �j � 2k, we find the unit tangent vector at (1, 1, 0) to be, T(0) �, , r¿(0), �j � 2k, 1, 2, �, ��, j�, k, 冟 r¿(0) 冟, 11 � 4, 15, 15

Page 11 :

994, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , y, π, r 3, , ( ), , ( , √3 ), 3, 2, , r (0), , C, 1, , π, r 3, , 0, , r(0), , ( ), , EXAMPLE 2 Find the tangent vectors to the plane curve C defined by the vector function r(t) � 3 cos ti � 2 sin tj at the points where t � 0 and t � p>3. Make a sketch, of C, and display the position vectors r(0) and r(p>3) and the tangent vectors r¿(0), and r¿(p>3)., Solution, , The tangent vector to the curve C at any point is given by, , (3, 0) x, , �2, , FIGURE 2, The vectors r¿(0) and r¿(p>3) are tangent to the curve at the points (3, 0), and 1 32, 13 2 , respectively., , r¿(t) � �3 sin ti � 2 cos tj, In particular, the tangent vectors at the points where t � 0 and t � p>3 are, r¿(0) � 2j, , and, , p, 313, r¿a b � �, i�j, 3, 2, , These vectors are shown emanating from their points of tangency at (3, 0) and, in Figure 2., , 1 32, 13 2, , EXAMPLE 3 Find parametric equations for the tangent line to the helix with parametric equations, x � 3 cos t, , y � 2 sin t, , z�t, , at the point where t � p>6., Solution, , The vector function that describes the helix is, r(t) � 3 cos ti � 2 sin tj � tk, , The tangent vector at any point on the helix is, r¿(t) � �3 sin ti � 2 cos tj � k, In particular, the tangent vector at the point, , p, 1 313, 2 , 1, 6 2 , where t � p>6, is, , p, 3, r¿a b � � i � 13j � k, 6, 2, , p, Finally, we observe that the required tangent line passes through the point 1 313, 2 , 1, 6 2, and has the same direction as the tangent vector r¿(p>6). Using Equation (1) of Section 11.5, we see that the parametric equations of this line are, , x�, , 313, 3, � t,, 2, 2, , y � 1 � 13t,, , and, , z�, , p, �t, 6, , Higher-Order Derivatives, Higher-order derivatives of vector functions are obtained by successive differentiation, of the lower-order derivatives of the function. For example, the second derivative of, r(t) is, r⬙(t) �, , d, r¿(t) � f ⬙(t)i � t⬙(t)j � h⬙(t)k, dt, , EXAMPLE 4 Find r⬙(t) if r(t) � 2e3t i � ln tj � sin tk., Solution, , We have, r¿(t) � 6e3t i �, , 1, j � cos tk, t

Page 12 :

12.2, , Differentiation and Integration of Vector-Valued Functions, , 995, , and, r⬙(t) � 18e3t i �, , 1, t2, , j � sin tk, , Rules of Differentiation, The following theorem gives the rules of differentiation for vector functions. As you, might expect, some of the rules are similar to the differentiation rules of Chapter 2., , THEOREM 2 Rules of Differentiation, Suppose that u and v are differentiable vector functions, f is a differentiable realvalued function, and c is a scalar. Then, 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., , d, dt, d, dt, d, dt, d, dt, d, dt, d, dt, , [u(t) � v(t)] � u¿(t) � v¿(t), [cu(t)] � cu¿(t), [ f(t)u(t)] � f ¿(t)u(t) � f(t)u¿(t), [u(t) ⴢ v(t)] � u¿(t) ⴢ v(t) � u(t) ⴢ v¿(t), [u(t), , v(t)] � u¿(t), , v(t) � u(t), , [u( f(t))] � u¿( f(t))f ¿(t), , v¿(t), , Chain Rule, , We will prove Rule 4 and leave the proofs of the other rules as exercises., , PROOF Let, u(t) � f1 (t)i � t1 (t)j � h 1 (t)k, , and, , v(t) � f2(t)i � t2 (t)j � h 2 (t)k, , Then, u(t) ⴢ v(t) � f1(t)f2(t) � t1(t)t2 (t) � h 1 (t)h 2 (t), Therefore, d, [u(t) ⴢ v(t)] � [f 1œ (t)f2(t) � t1œ (t)t2 (t) � h 1œ (t)h 2 (t)], dt, � [f1(t)f 2œ (t) � t1(t)t2œ (t) � h 1(t)h 2œ (t)], � u¿(t) ⴢ v(t) � u(t) ⴢ v¿(t), , EXAMPLE 5 Suppose that v is a differentiable vector function of constant length c., Show that v ⴢ v¿ � 0. In other words, the vector v and its tangent vector v¿ must be, orthogonal., Solution, , The condition on v implies that, v ⴢ v � 冟 v 冟2 � c2

Page 14 :

12.2, , Differentiation and Integration of Vector-Valued Functions, , 997, , where C1, C2, and C3 are constants of integration. We can rewrite the last expression as, 1, 1, 1, a t 2 � tbi � sin 2tj � e3t k � C1i � C2 j � C3k, 2, 2, 3, or, upon letting C � C1i � C2 j � C3k,, , 冮 r(t) dt � a 2 t, 1, , 2, , � tbi �, , 1, 1, sin 2tj � e3t k � C, 2, 3, , where C is a constant (vector) of integration., Note, , In general, the indefinite integral of r can be written as, , 冮 r(t) dt � R(t) � C, where C is an arbitrary constant vector and R¿(t) � r(t)., , EXAMPLE 8 Find the antiderivative of r¿(t) � cos ti � e�tj � 1tk satisfying the, , initial condition r(0) � i � 2j � 3k., Solution, , We have, , 冮 r¿(t) dt � 冮 (cos ti � e, , r(t) �, , �t, , j � t 1>2 k) dt, , 2 3>2, t k�C, 3, , � sin ti � e�tj �, , where C is a constant (vector) of integration. To determine C, we use the condition, r(0) � i � 2j � 3k to obtain, r(0) � 0i � j � 0k � C � i � 2j � 3k, from which we find C � i � 3j � 3k. Therefore,, 2 3>2, t k � i � 3j � 3k, 3, 2, � (1 � sin t)i � (3 � e�t)j � a3 � t 3>2 bk, 3, , r(t) � sin ti � e�tj �, , 1, , EXAMPLE 9 Evaluate, , 冮 r(t) dt if r(t) � t i � t � 1 j � e, 1, , 2, , �t, , k., , 0, , Solution, , 冮, , 1, , 1, , r(t) dt �, , 0, , 冮 at i � t � 1 j � e, 2, , 1, , �t, , kb dt, , 0, , �c, , 冮, , 0, , 1, , t 2dtdi � c, , 冮, , 0, , 1, , 1, dtd j � c, t�1, , 1, , 冮e, , �t, , 0, , 1 1, 1, 1, � c t 3 d i � Cln(t � 1) D 0 j � C�e�t D 0 k, 3 0, �, , 1, 1, i � ln 2j � a1 � bk, e, 3, , dtdk

Page 15 :

998, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , 12.2, , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, 3. Let r(t) � f(t)i � t(t)j � h(t)k., a. What is the indefinite integral of r with respect to t?, b. What is the definite integral of r over the interval [a, b]?, , 1. a. What is the derivative of a vector function?, b. If r(t) � f(t)i � t(t)j � h(t)k, what is r¿(t)?, c. Give an example of a function r(t) such that r¿(0) does, not exist., 2. If w(t) � u( f(t)) v( f(t)) , what is w¿(t) ? Assume that u, v,, and f are all differentiable., , 12.2, , EXERCISES, 20. r(t) � t sin ti � t cos tj � tk; t �, , In Exercises 1–8, find r¿(t) and r⬙(t)., 1. r(t) � ti � t 2j � t 3 k, , In Exercises 21–26, find parametric equations for the tangent, line to the curve with the given parametric equations at the point, with the indicated value of t., , 1, j � ln tk, t, , 2. r(t) � 1t i �, , 3. r(t) � 具t 2 � 1, 2t 2 � 1典, 5. r(t) � 具t cos t � sin t, t sin t � cos t典, 7. r(t) � e�t sin ti � e�t cos tj � tan�1 tk, 8. r(t) � 具sin�1 t, sec t, ln 冟 t 冟典, In Exercises 9–16, (a) find r(a) and r¿(a) at the given value of a., (b) Sketch the curve defined by r and the vectors r(a) and r¿(a), on the same set of axes., , 10. r(t) � sin ti � cos tj;, , a�2, , 12. r(t) � t 2i � t 3j;, , p, 3, , 14. r(t) � 具e , e, , p, 4, , 25. x � t cos t, y � t sin t, z � tet; t �, , p, 6, , 27., , 冮 (ti � 2t j � 3k) dt, , 28., , 冮 (ti � t j � t k) dt, , a�1, , 29., , 典; a � 0, 30., , p, a�, 4, , 16. r(t) � b cos3 ti � b sin3 tj;, , 2, , 3, , a�, , p, 4, , t�1, , 18. r(t) � 具e , te , (t � 1)e 典;, 2t, , 冮 a 1t i � t j � t, 1, , 冮, , 2, , 1, , In Exercises 17–20, find the unit tangent vector T(t) at the point, corresponding to the given value of the parameter t., �t, , 2, , 1, , �2t, , 17. r(t) � ti � 2tj � 3tk;, , y � t 2, z � 2 sin t;, , 26. x � e�t cos t, y � e�t sin t, z � sin�1t; t � 0, , a�1, , 15. r(t) � sec ti � 2 tan tj;, , t, , t�, , 24. x � 2 cos t,, , 0, , 13. r(t) � (2 � 3t)i � (1 � 2t)j;, t, , 1, 2, , z� 2, ; t�2, t�1, t �4, , In Exercises 27–34, find or evaluate the integral., , p, 4, , 11. r(t) � 具4 cos t, 2 sin t典; a �, , t�1, , 22. x � 1 � t, y � t 2 � 4, z � 1t; t � 4, 23. x � 1t � 2, y �, , 6. r(t) � e�t i � tet j � e�2t k, , a�, , z � t 3;, , 21. x � t, y � t 2,, , 4. r(t) � 具t cos t, t sin t, tan t典, , 9. r(t) � 1t i � (t � 4)j;, , p, 2, , t�0, , c 1t � 1 i �, , 3>2, , kb dt, , 1, j � (2t � 1)5 kd dt, 1t, , 31., , 冮 (sin 2ti � cos 2tj � e, , 32., , 冮 (te i � 2j � sec, , 33., , 冮 (t cos ti � t sin t j � te k) dt, , 34., , 冮 c1 � t, , p, 19. r(t) � 2 sin 2ti � 3 cos 2tj � 3k; t �, 6, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login., , t, , 2, , 2, , i�, , k) dt, , tk) dt, , 2, , 1, , �t, , t, 1 � 2t 2, , t2, , j�, , 1, 21 � t 2, , kd dt

Page 16 :

12.2, In Exercises 35–40, find r(t) satisfying the given conditions., 35. r¿(t) � 2i � 4tj � 6t k;, , d, [r(t) ⴢ (u(t) v(t))], dt, � r¿(t) ⴢ [u(t) v(t)] � r(t) ⴢ [u¿(t), , 1, 36. r¿(t) � 2 sin 2ti � 3 cos 2tj � tk; r(0) � i � 2j � k, 2, �t, , � r(t) ⴢ [u(t), , 37. r¿(t) � 2e i � 3e j � e k; r(0) � i � j � k, 2t, , 999, , 54. Prove that, , r(0) � i � k, , 2, , Differentiation and Integration of Vector-Valued Functions, , t, , v(t)], , v¿(t)], , 1, k; r(3) � i � j � 2k, t, , In Exercises 55–58, find the indicated derivative., , r¿(0) � i � k,, , 55., , d, 1, cr(�t) � ra b d, dt, t, , 56., , d, [r(2t) ⴢ r(t 2)], dt, , In Exercises 41–46, let u(t) � t 2i � 2tj � 2k,, v(t) � cos ti � sin tj � t 2k, and f(t) � e2t., , 57., , d, [r(t) ⴢ (r¿(t), dt, , 41. Show that, , d, [u(t) � v(t)] � u¿(t) � v¿(t)., dt, , 58., , d, {u(t), dt, , 42. Show that, , d, [3u(t)] � 3u¿(t)., dt, , In Exercises 59 and 60, suppose that u and v are integrable on, [a, b] and that c is a scalar. Prove each property., , 43. Show that, , d, [ f(t)u(t)] � f ¿(t)u(t) � f(t)u¿(t)., dt, , 59., , 38. r¿(t) � 1t � 1 i �, , t, t2 � 1, , j�, , 39. r⬙(t) � 1t i � sec2 tj � et k;, r(0) � 2i � j � k, , 40. r⬙(t) � 3 cos 2ti � 4 sin 2tj � k;, r(0) � 2i � j � k, , r¿(0) � i � 2j,, , r⬙(t))], , [v(t), , w(t)]}, , b, , b, , b, , 冮 [u(t) � v(t)] dt � 冮 u(t) dt � 冮 v(t) dt, a, , a, , b, , a, , b, , 冮 cu(t) dt � c冮 u(t) dt, , 44. Show that, , d, [u(t) ⴢ v(t)] � u¿(t) ⴢ v(t) � u(t) ⴢ v¿(t)., dt, , 60., , 45. Show that, , d, [u(t), dt, , 61. a. Suppose that r is integrable on [a, b] and that c is a constant vector. Prove that, , v(t)] � u¿(t), , v(t) � u(t), , v¿(t)., , a, , a, , 冮, , d, 46. Show that [u( f(t))] � u¿[ f(t)]f ¿(t) ., dt, , b, , b, , c ⴢ r(t) dt � c ⴢ, , a, , a, , b. Verify this property directly for the vector function, , In Exercises 47–52, suppose u and v are differentiable vector, functions, f is a differentiable real-valued function, and c is a, scalar. Prove each rule., d, [u(t) � v(t)] � u¿(t) � v¿(t), 47., dt, , r(t) � sin ti � cos tj � tk,, c � 2i � 3j � k,, , and, , d, [u(t) � v(t)] � u¿(t) � v¿(t), dt, , 49., , d, [cu(t)] � cu¿(t), dt, , 62. If c is a constant vector, then, , 50., , d, [ f(t)u(t)] � f ¿(t)u(t) � f(t)u¿(t), dt, , 63., , 51., , d, [u(t), dt, , v(t) � u(t), , v¿(t), , d, [r(t), dt, , r¿(t)] � r(t), , b�p, , d, (c) � 0., dt, , d, (冟 u 冟2) � 2u ⴢ u¿, dt, , 64. If r¿(t) � 0, then r(t) � c, where c is an arbitrary constant, vector., 65. If r is differentiable and r(t) ⴢ r¿(t) � 0 for all t, then r must, have constant length., , d, [u( f(t))] � u¿( f(t))f ¿(t), 52., dt, 53. Prove that, , a � 0,, , In Exercises 62–65, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why. If it is false, explain why or give, an example to show that it is false., , 48., , v(t)] � u¿(t), , 冮 r(t) dt, , r⬙(t).

Page 17 :

1000, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , 12.3 Arc Length and Curvature, Arc Length, In Section 10.3 we saw that the length of the plane curve given by the parametric equations x � f(t) and y � t(t), where a � t � b, is, L�, , 冮, , b, , a, , dy 2, dx 2, b � a b dt �, B dt, dt, a, , b, , 冮 2[ f ¿(t)], , 2, , � [t¿(t)]2 dt, , a, , Now, suppose that C is described by the vector function r(t) � f(t)i � t(t)j, instead. Then, r¿(t) � f ¿(t)i � t¿(t)j, and, 冟 r¿(t) 冟 � 2r¿(t) ⴢ r¿(t) � 2[ f ¿(t)]2 � [t¿(t)]2, from which we see that L can also be written in the form, b, , L�, , 冮 冟 r¿(t) 冟 dt, a, , A similar formula for calculating the length of a space curve is contained in the following theorem., , THEOREM 1 Arc Length of a Space Curve, Let C be a curve given by the vector function, r(t) � f(t)i � t(t)j � h(t)k, , a�t�b, , where f ¿, t¿, and h¿ are continuous. If C is traversed exactly once as t increases, from a to b, then its length is given by, L�, , 冮, , b, , b, , 2[ f ¿(t)]2 � [t¿(t)]2 � [h¿(t)]2 dt �, , a, , z, , 冮 冟 r¿(t) 冟 dt, a, , EXAMPLE 1 Find the length of the arc of the helix C given by the vector function, r(t) � 2 cos ti � 2 sin tj � tk, where 0 � t � 2p, as shown in Figure 1., Solution, , We first compute, r¿(t) � �2 sin ti � 2 cos tj � k, , C, , Then, using Theorem 1, we see that the length of the arc in question is, y, , x, , FIGURE 1, The length of the arc of the helix, for 0 � t � 2p is 2 15p., , L�, , 冮, , 2p, , 冮, , 2p, , 冟 r¿(t) 冟 dt �, , 0, , �, , 冮, , 2p, , 24 sin2 t � 4 cos2 t � 1 dt, , 0, , 0, , 15 dt � 215p

Page 18 :

12.3, y, , Arc Length and Curvature, , 1001, , Smooth Curves, , Cusp, , x, , FIGURE 2, The curve defined by r(t) � t 3i � t 2 j, is smooth everywhere except at (0, 0)., , A curve that is defined by a vector function r on a parameter interval I is said to be, smooth if r¿(t) is continuous and r¿(t) 0 for all t in I with the possible exception of, the endpoints. For example, the plane curve defined by r(t) � t 3 i � t 2 j is smooth, everywhere except at the point (0, 0) corresponding to t � 0. To see this, we compute, r¿(t) � 3t 2 i � 2tj and note that r¿(0) � 0. The curve is shown in Figure 2. The point, (0, 0) where the curve has a sharp corner is called a cusp., , Arc Length Parameter, The curve C described by the vector function r(t) with parameter t in some parameter, interval I is said to be parametrized by t. A curve C can have more than one parametrization. For example, the helix represented by the vector function, r1(t) � 2 cos ti � 3 sin tj � tk, , 2p � t � 4p, , with parameter t is also represented by the function, r2 (u) � 2 cos eu i � 3 sin eu j � eu k, , ln 2p � u � ln 4p, , with parameter u, where t and u are related by t � eu., A useful parametrization of a curve C is obtained by using the arc length of C as, its parameter. To see how this is done, we need the following definition., , DEFINITION Arc Length Function, Suppose that C is a smooth curve described by r(t) � f(t)i � t(t)j � h(t)k,, where a � t � b. Then the arc length function s is defined by, t, , s(t) �, , 冮 冟 r¿(u) 冟 du, , (1), , a, , Thus, s(t) is the length of that part of C (shown in red) between r(a) and r(t) . (See, Figure 3.) Because s(a) � 0, we see that the length L of C from t � a to t � b is, b, , s(b) �, , 冮 冟 r¿(t) 冟 dt, a, , z, , C, , r(b), , r(t), , FIGURE 3, The arc length function s(t) gives the, length of that part of C corresponding, to the parameter interval [a, t]., , r(a), [, a, , t, , ], b, , Parameter interval, , 0, t, , y, x

Page 19 :

1002, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , If we differentiate both sides of Equation (1) with respect to t and use the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, Part 2, we obtain, ds, � 冟 r¿(t) 冟, dt, , (2), , ds � 冟 r¿(t) 冟 dt, , (3), , or, in differential form,, , The following example shows how to parametrize a curve in terms of its arc length., , EXAMPLE 2 Find the arc length function s(t) for the circle C in the plane described, by, r(t) � 2 cos ti � 2 sin tj, , 0 � t � 2p, , Then use your result to find a parametrization of C in terms of s., Solution, , We first compute r¿(t) � �2 sin ti � 2 cos tj, and then compute, 冟 r¿(t) 冟 � 24 sin2 t � 4 cos2 t � 2, , Using Equation (1), we obtain, s(t) �, , 冮, , t, , 冟 r¿(u) 冟 du �, , 0, , t, , 冮 2 du � 2t, , 0 � t � 2p, , 0, , Writing s for s(t), we have s � 2t, where 0 � t � 2p, which when solved for t, yields, t � t(s) � s>2. Substituting this value of t into the equation for r(t) gives, s, s, r(t(s)) � 2 cosa bi � 2 sina bj, 2, 2, Finally, since s(0) � 0 and s(2p) � 4p, we see that the parameter interval for this, parametrization by the arc length s is [0, 4p]. (See Figure 4.), y, , FIGURE 4, The curve C is described by, r(t) � 2 cos ti � 2 sin tj,, where 0 � t � 2p, and, r(t(s)) � 2 cos(s>2)i � 2 sin(s>2)j,, where 0 � s � 4p., , C, [, 0, , ], 2π, , �2, , 2, , x, , [, 0, , t, , Parameter interval for r(t), , ], 4π, , s, , Parameter interval for r(s), , One reason for using the arc length of a curve C as the parameter stems from the, fact that its tangent vector r¿(s) has unit length; that is, r¿(s) is a unit tangent vector., Consider the circle of Example 2. Here,, s, s, r¿(s) � �sina bi � cosa bj, 2, 2, so, 冟 r¿(s) 冟 �, , B, , s, s, sin2 a b � cos2 a b � 1, 2, 2

Page 20 :

12.3, z, , Arc Length and Curvature, , 1003, , Curvature, , C, 0, y, x, , FIGURE 5, The unit tangent vector T(s) turns, faster along the stretch of the path, where the turn is sharper., , Figure 5 depicts the flight path C of an aerobatic plane as it executes a maneuver. Suppose that the smooth curve C is defined by the vector function r(s), where s is the arc, length parameter. Then the unit tangent vector function T(s) � r¿(s) gives the direction of the plane at the point on C corresponding to the parameter value s., In Figure 5 we have drawn the unit tangent vector T(s) to C corresponding to several values of s. Observe that T(s) turns rather slowly along a stretch of the flight path, that is relatively straight but turns more quickly along a stretch of the curve where the, plane executes a sharp turn., To measure how quickly a curve bends, we introduce the notion of the curvature, of a curve. Specifically, we define the curvature at a point on a curve C to be the magnitude of the rate of change of the unit tangent vector with respect to arc length at that, point., , DEFINITION Curvature, Let C be a smooth curve defined by r(s), where s is the arc length of the parameter. Then the curvature of C at s is, k(s) � `, , dT, ` � 冟 T¿(s) 冟, ds, , where T is the unit tangent vector., , Note, , The Greek letter k is read “kappa.”, , Although the use of the arc length parameter s provides us with a natural way for, defining the curvature of a curve, it is generally easier to find the curvature in terms, of the parameter t. To see how this is done, let’s apply the Chain Rule (Rule 6 in Section 12.2) to write, dT, dT ds, �, dt, ds dt, Then, dT, `, `, dT, dt, `�, k(s) � `, ds, ds, ` `, dt, Since ds>dt � 冟 r¿(t) 冟 by Equation (2), we are led to the following formula:, k(t) �, , 冟 T¿(t) 冟, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, , (4), , EXAMPLE 3 Find the curvature of a circle of radius a., Solution Without loss of generality we may take the circle C with center at the origin. This circle is represented by the vector function, r(t) � a cos ti � a sin tj, , 0 � t � 2p

Page 21 :

1004, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , Now, r¿(t) � �a sin ti � a cos tj, so, 冟 r¿(t) 冟 � 2a 2 sin2 t � a 2 cos2 t � a, Therefore,, T(t) �, , r¿(t), � �sin ti � cos tj, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, , Next, we compute, T¿(t) � �cos ti � sin tj, and, 冟 T¿(t) 冟 � 2cos2 t � sin2 t � 1, Finally, using Equation (4), we obtain, 冟 T¿(t) 冟, 1, �, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, a, , k(t) �, , Therefore, the curvature at every point on the circle of radius a is 1>a. This result, agrees with our intuition: A big circle has a small curvature and vice versa., The following formula expresses the curvature in terms of the vector function r and, its derivatives., , THEOREM 2 Formula for Finding Curvature, Let C be a smooth curve given by the vector function r. Then the curvature of, C at any point on C corresponding to t is given by, k(t) �, , 冟 r¿(t), , r⬙(t) 冟, 冟 r¿(t) 冟3, , PROOF We begin by recalling that, T(t) �, , r¿(t), 冟 r¿(t) 冟, , Since 冟 r¿(t) 冟 � ds>dt, we have, r¿(t) �, , ds, T(t), dt, , Differentiating both sides of this equation with respect to t and using Rule 3 in Section 12.2, we obtain, r⬙(t) �, , d 2s, dt, , 2, , T(t) �, , ds, T¿(t), dt

Page 23 :

1006, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , If a plane curve C happens to be contained in the graph of a function defined by, y � f(x), then we can use the following formula to compute its curvature., , THEOREM 3 Formula for the Curvature of the Graph of a Function, If C is the graph of a twice differentiable function f, then the curvature at the, point (x, y) where y � f(x) is given by, k(x) �, , 冟 f ⬙(x) 冟, [1 � [f ¿(x)] ], , 2 3>2, , �, , 冟 y⬙ 冟, , (5), , [1 � (y¿)2]3>2, , PROOF Using x as the parameter, we can represent C by the vector function r(x) �, xi � f(x)j � 0k. Differentiating r(x) with respect to x successively, we obtain, r¿(x) � i � f ¿(x)j � 0k, , r⬙(x) � 0i � f ⬙(x)j � 0k, , and, , from which we obtain, r¿(x), , i, r⬙(x) � † 1, 0, , j, f ¿(x), f ⬙(x), , k, 0 † � f ⬙(x)k, 0, , and, 冟 r¿(x), , r⬙(x) 冟 � 冟 f ⬙(x) 冟, , Also,, 冟 r¿(x) 冟 � 21 � [f ¿(x)]2, Therefore,, k(x) �, , 冟 r¿(x), , 冟 f ⬙(x) 冟, r⬙(x) 冟, �, 3, 冟 r¿(x) 冟, [1 � [f ¿(x)]2]3>2, , EXAMPLE 5, a. Find the curvature of the parabola y � 14 x 2 at the points where x � 0 and x � 1., b. Find the point(s) where the curvature is largest., Solution, a. We first compute y¿ � 12 x and y⬙ � 12. Then using Theorem 3, we find the curvature at any point (x, y) on the parabola y � 12 x 2 to be, k(x) �, , 冟 y⬙ 冟, [1 � (y¿) ], , 2 3>2, , �, , 11 �, , 1, 2, 1 2 3>2, 4x, , 2, , �, , 4, (4 � x 2)3>2, , In particular, the curvature at the point (0, 0) , where x � 0, is, 4, , k(0) �, , (4 � x ), , 2 3>2, , `, , �, x�0, , and the curvature at the point 1 1, 2 , where x � 1, is, , 1, 2, , 1, 4, , k(1) �, , 4, , (4 � x ), , 2 3>2, , `, , �, x�1, , 4, , 53>2, , ⬇ 0.358

Page 24 :

12.3, , b. To find the value of x at which k is largest, we compute, , y, 4, , k¿(x) �, , 3, , 1, �2, , d, 12x, [4(4 � x 2)�3>2] � �6(4 � x 2)�5>2 (2x) � �, dx, (4 � x 2)5>2, , Setting k¿(x) � 0 yields the sole critical point x � 0. We leave it to you to show, that x � 0 does give the absolute maximum value of k(x)., , 2, , �4, , 1007, , Arc Length and Curvature, , 0, , 2, , FIGURE 6, The graph of y � 14 x 2, , 4, , x, , The graph of y � 14 x 2 is shown in Figure 6., , Radius of Curvature, Suppose that C is a plane curve with curvature k at the point P. Then the reciprocal of, the curvature, r � 1>k, is called the radius of curvature of C at P. The radius of curvature at any point P on a curve C is the radius of the circle that best “fits” the curve, at that point. This circle, which lies on the concave side of the curve and shares a common tangent line with the curve at P, is called the circle of curvature or osculating, circle. (See Figure 7.), The center of the circle is called the center of curvature. As an example, the curvature of the parabola y � 14 x 2 of Example 5 at the point (0, 0) was found to be 12., Therefore, the radius of curvature of the parabola at (0, 0) is r � 1>(1/2) � 2. The circle of curvature is shown in Figure 8. Its equation is x 2 � (y � 2)2 � 4., y, , y, C, P, ®, , 3, 2, 1, , 0, , x, , FIGURE 7, The radius of curvature at P is the, radius of the circle that best fits the, curve C at P., , 12.3, , �4, , �2, , 0, , 2, , 4, , x, , FIGURE 8, The circle of curvature is tangent to the, parabola., , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, , 1. Give the formula for finding the arc length of the curve C, defined by r(t) � 具 f(t), t(t), h(t)典 for a � t � b. What condition, if any, must be imposed on C?, 2. a. What is a smooth curve?, b. Give an example of a curve in 3-space that is not, smooth., 3. a. What is the arc length function associated with, r(t) � 具 f(t), t(t), h(t)典, where a � t � b?, b. If a curve is parametrized in terms of its arc length, what, is the unit tangent vector T(s)? What is T(t), where t is, not the arc length parameter?, , 4. a. What is the curvature of a smooth curve C at s, where s, is the arc length parameter?, b. If t is not the arc length parameter, what is the curvature, of C at t?, c. What is the radius of curvature of a curve C at a point P, on C ?

Page 25 :

1008, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , 12.3, , EXERCISES, In Exercises 29–32, find the point(s) on the curve at which the, curvature is largest., , In Exercises 1–8, find the length of the curve., 1. r(t) � ti � 2tj � 3tk, 0 � t � 4, 2. r(t) � 具5t, 3t 2, 4t 2典,, , 0�t�2, , 3. r(t) � 4 sin ti � 3tj � 4 cos tk,, , 0 � t � 2p, , 4. r(t) � a cos ti � a sin tj � btk, 0 � t � 2p, 5. r(t) � 具et cos t, et sin t, et典,, , 0 � t � 2p, , 6. r(t) � t 2 i � t cos tj � t sin tk,, 7. r(t) � 2ti � t j � ln tk,, 2, , 0�t�1, , 29. y � ex, , 30. y � ln x, , 31. xy � 1, , 32. 4x 2 � 9y 2 � 36, , In Exercises 33–36, match the curve with the graph of its curvature y � k(x) in (a)–(d)., 33., , 1�t�e, , 8. r(t) � (cos t � t sin t)i � (sin t � t cos t)j � t 2 k,, 0 � t � p2, In Exercises 9 and 10, use a calculator or computer to graph the, curve represented by r(t), and find the length of the curve for t, defined on the indicated interval., 9. r(t) � t sin ti � t cos tj � tk;, , 10. r(t) � 2 sin ti � 2 cos tj � 12 t 2 k;, , �4, , �2, , 13. r(t) � e cos ti � e sin tj � e k,, , t�0, , 14. r(t) � a cos3 ti � a sin3 tj � k,, , 0 � t � p2, , t, , t, , 36., , �1, , (a), , 0, , 2 x, , 1, , �4, , �2, , (b), , y, , 0, , 4 x, , 2, , 4 x, , y, 1.0, 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, , �2 �1 0, , 18. r(t) � (1 � t)i � (1 � t)j � 3t 2 k, , (c), , 1, , 2, , x, , 20. r(t) � 具et cos t, et sin t, et典, In Exercises 21–26, use Theorem 3 to find the curvature of the, curve., , �4, (d), , y, , 19. r(t) � 2 sin ti � 2 cos tj � 2tk, , 24. y � ln x, , 2, , 4, , 2, , 17. r(t) � ti � 12 t 2 j � t 2 k, , 23. y � sin 2x, , 10 x, , 3, , 16. r(t) � ti � j � t 2 k, , 22. y � x 4, , 5, , y, 8, , 1, , 21. y � x 3 � 1, , 0, , 1, �2, , 15. r(t) � 2ti � 2tj � k, , 25. y � e, , 4 x, , 2, , 1, , In Exercises 15–20, use Theorem 2 to find the curvature of the, curve., , �x2, , 1, , 0, , 2, , t�0, t�0, , t, , 2, , 3, , In Exercises 11–14, find the arc length function s(t) for the curve, defined by r(t). Then use this result to find a parametrization of, C in terms of s., 12. r(t) � 4 sin ti � 4 cos tj � 3tk,, , 3, , y, , [0, 2p], , 11. r(t) � (1 � t)i � (1 � 2t)j � 3tk,, , y, 4, , �10 �5, , 35., , [0, 2p], , 34., , y, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, , �2, , 0, y, , 8, , 8, , 6, , 6, , 4, , 4, , 2, �3 �2 �1 0, , 26. y � sec x, , 1, , 2, , 3 x, , �3 �2 �1 0, , 1, , 2, , 3 x, , 2, , 27. Find the point(s) on the graph of y � e�x at which the, curvature is zero., 28. Find an equation of the circle of curvature for the graph of, f(x) � x � (1>x) at the point (1, 2) . Sketch the graph of f, and the circle of curvature., , In Exercises 37 and 38, find the curvature function k(x) of the, curve. Then use a calculator or computer to graph both the, curve and its curvature function k(x) on the same set of axes., 37. y � e�x, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login., , 2, , 38. y � ln(1 � x 2)

Page 26 :

12.3, 39. Suppose that C is a smooth curve with parametric equations, x � f(t), y � t(t). Using Theorem 2, show that the curvature, at the point (x, y) corresponding to any value of t is, k(t) �, , Arc Length and Curvature, , 1009, , of cornu makes the curve useful in highway design: It provides, a gradual transition from a straight road (zero curvature) to a, curved road (with positive curvature), such as an exit ramp., , 冟 f ¿(t)t⬙(t) � t¿(t)f ⬙(t) 冟, , y, , {[f ¿(t)]2 � [t¿(t)]2}3>2, , In Exercises 40 and 41, use the formula in Exercise 39 to find, the curvature of the curve., 40. x � cos t,, , y � t sin t, , 41. x � t � sin t,, , x, , y � 1 � cos t, , 42. a. The curvature of the curve C at P shown in the figure is, 2. Sketch the osculating circle at P. (Use the tangent line, shown at P as an aid.), b. What is the curvature of C at Q?, 46. Suppose that the curve C is described by a polar equation, r � f(u). Show that the curvature at the point (r, u) is, given by, , y, 5, 8 in., , P, , k(u) �, , C, , 冟 2(r¿)2 � rr ⬙ � r 2 冟, [(r¿)2 � r 2]3>2, , Hint: Represent C by r(u) � r cos ui � r sin uj., Q, 0, , x, , 43. a. Find the curvature at the point (x, y) on the ellipse, , x � a cos t, , b. Find the curvature and the equation of the osculating, circle at the points (3, 0) and (0, 2)., c. Sketch the graph of the ellipse and the osculating circles, of part (b)., 44. Find the curvature k(t) for the curve with parametric, equations, , What happens to k(t) as t approaches 0?, Note: The curve is not smooth at t � 0., , 45. The spiral of cornu is defined by the parametric equations, x�, , 冮, , 0, , t, , cosa, , pu 2, b du, 2, , y�, , 48. r � eu, , 冮, , t, , 0, , sina, , y � a sin t, , z � bt, , where a � 0, is given by k(t) � a>(a � b 2)., 2, , 50. Find the curvature at the point (x, y, z) on an elliptic helix, with parametric equations, x � a cos t, , y � b sin t, , where a, b, and c are positive and a, , z � ct, b., , 51. Find the arc length of r(t) � t cos ti � t sin tj � tk, where, 0 � t � 2p., , y � t3, , and, , 47. r � 1 � sin u, , 49. Show that the curvature at every point on the helix, , y2, x2, �, �1, 9, 4, , x � t2, , In Exercises 47 and 48, use the formula in Exercise 46 to find, the curvature of the curve., , pu 2, b du, 2, , and was encountered in Exercise 45 of Section 10.3. Its, graph follows., dy, d 2y, a. Find, and 2 ., dx, dx, b. Find the curvature of the spiral., Note: The curvature k(t) increases from 0 at a constant rate with, respect to t as t increases from t � 0. This property of the spiral, , 52. Find the curvature of the graph of x 3 � y 3 � 9xy (folium, of Descartes) at the point (2, 4) accurate to four decimal, places., In Exercises 53–58, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why. If it is false, explain why or give, an example to show that it is false., 53. If C is a smooth curve in the xy-plane defined by, r(t) � x(t)i � y(t)j on a parameter interval I, then, dy>dx is defined at every point on the curve., 54. The curve defined by r(t) � 具t, 冟 t 冟典 is smooth.

Page 27 :

1010, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, 57. The radius of curvature of the plane curve y � 2a 2 � x 2 is, constant at each point on the curve., , 55. If the graph of a twice differentiable function f has an inflection point at a, then the curvature at the point (a, f(a)) is, zero., , 58. If r¿(t) is continuous for all t in an interval I, then r defines, a smooth curve., , 56. If C is the curve defined by the parametric equations, x � 1 � 2t, , y � 2 � 3t, , z � 4t, , then d T>ds � 0, where T is the unit tangent vector to C., , 12.4, , Velocity and Acceleration, Velocity, Acceleration, and Speed, The curve C in Figure 1 is the flight path of a fighter plane. We can represent C by the, vector function, r(t) � f(t)i � t(t)j � h(t)k, , t僆I, , where we think of the parameter interval I as a time interval and use r(t) to indicate, the position of the plane at time t., z, P, r (t), , FIGURE 1, The position vector r(t) gives, the position of a fighter plane at, time t, and its derivative r¿(t) gives, the plane’s velocity at time t., , C, [, a, , t, , ], b, , Parameter interval (time interval), , r(t), 0, , t, , y, x, , From Sections 12.2 and 12.3 we know that the vector r¿(t) has the following properties:, 1. r¿(t) is tangent to C at the point P corresponding to time t., ds, 2. 冟 r¿(t) 冟 � ., dt, Since ds>dt is the rate of change of the distance (measured along the arc) with respect, to time, it measures the speed of the plane. Thus, the vector r¿(t) gives both the speed, and the direction of the plane. In other words, it makes sense to define the velocity vector of the plane at time t to be r¿(t), the rate of change of its position vector with respect, to time. Similarly, we define the acceleration vector of the plane at time t to be r⬙(t),, the rate of change of its velocity vector with respect to time., To gain insight into the nature of the acceleration vector, let’s refer to Figure 2., Here, t is fixed, and h is a small number. The vector r¿(t) is tangent to the flight path, at the tip of the position vector r(t), and r¿(t � h) is tangent to the flight path at the, tip of r(t � h) . The vector, r¿(t � h) � r¿(t), h

Page 28 :

12.4, , Velocity and Acceleration, , 1011, , points in the general direction in which the plane is turning. Therefore, the acceleration vector, r⬙(t) �, , r¿(t � h) � r¿(t), d, r¿(t) � lim, dt, h→0, h, , points toward the concave side of the flight path as long as the direction of r¿(t) is, changing, in agreement with our intuition., z, , C, , r_______, (t � h) �____, r (t), h, , r (t � h), r (t � h) � r (t), , r(t � h), r (t), r(t), 0, , FIGURE 2, To find r¿(t � h) � r¿(t),, translate r¿(t � h) so that, its tail is at the tip of r(t)., , y, x, , Let’s summarize these definitions., , DEFINITIONS Velocity, Acceleration, and Speed, Let r(t) � f(t)i � t(t)j � h(t)k be the position vector of an object. If f, t, and, h are twice differentiable functions of t, then the velocity vector v(t), acceleration vector a(t), and speed 冟 v(t) 冟 of the object at time t are defined by, v(t) � r¿(t) � f ¿(t)i � t¿(t)j � h¿(t)k, a(t) � r⬙(t) � f ⬙(t)i � t⬙(t)j � h⬙(t)k, 冟 v(t) 冟 � 冟 r¿(t) 冟 � 2[ f ¿(t)]2 � [t¿(t)]2 � [h¿(t)]2, , EXAMPLE 1 The position of an object moving in a plane is given by, r(t) � t 2 i � tj, , t�0, , Find its velocity, acceleration, and speed when t � 2. Sketch the path of the object and, the vectors v(2) and a(2)., Solution, , The velocity and acceleration vectors of the object are, v(t) � r¿(t) � 2ti � j, , and, a(t) � r⬙(t) � 2i

Page 29 :

1012, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , Therefore, its velocity, acceleration, and speed when t � 2 are, v(2) � 4i � j, a(2) � 2i, , y, v(2), , and, 冟 v(2) 冟 � 116 � 1 � 117, , C, , 2, , a(2), , 1, 0, , 1, , 2, , 3, , x, , 4, , FIGURE 3, The path of the object C and the, vectors v(2) and a(2), , respectively., To sketch the path of the object, observe that the parametric equations of the curve, described by r(t) are x � t 2 and y � t. By eliminating t from these equations, we obtain, the rectangular equation x � y 2, where y � 0, which tells us that the path of the object, is contained in the graph of the parabola x � y 2. This path together with the vectors, v(2) and a(2) is shown in Figure 3., , EXAMPLE 2 Find the velocity vector, speed, and acceleration vector of an object that, moves along the plane curve C described by the position vector, y, , r(t) � 3 cos ti � 2 sin tj, , v(t), , 2, , Solution, , The velocity vector is, , a(t), �3, , 0, , v(t) � �3 sin ti � 2 cos tj, 3, , x, , The speed of the object at time t is, 冟 v(t) 冟 � 29 sin2 t � 4 cos2 t, , �2, , Finally, the acceleration vector is, FIGURE 4, The acceleration vector a points toward, the origin., , a(t) � �3 cos ti � 2 sin tj � �r(t), which shows the acceleration is directed toward the origin (see Figure 4)., , EXAMPLE 3 Find the velocity vector, acceleration vector, and speed of a particle, with position vector, r(t) � 1ti � t 2 j � e2t k, Solution, , t�0, , The required quantities are, v(t) � r¿(t) �, , 1 �1>2, 1, t, i � 2tj � 2e2t k �, i � 2tj � 2e2t k, 2, 21t, , 1, 1, a(t) � r⬙(t) � � t �3>2 i � 2j � 4e2t k � �, i � 2j � 4e2t k, 4, 42t 3, and, 冟 v(t) 冟 �, , 1, 21 � 16t 3 � 16te4t, � 4t 2 � 4e4t �, B 4t, 21t, , Suppose that we are given the velocity or acceleration vector of a moving object., Then it is possible to find the position vector of the object by integration, as is shown, in the next example.

Page 30 :

12.4, , Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo/, The Image Works, , Historical Biography, , Velocity and Acceleration, , 1013, , EXAMPLE 4 A moving object has an initial position and an initial velocity given, by the vectors r(0) � i � 2j � k and v(0) � i � 2k. Its acceleration at time t is, a(t) � 6ti � j � 2k. Find its velocity and position at time t., Solution Since v¿(t) � a(t), we can obtain v(t) by integrating both sides of this equation with respect to t. Thus,, v(t) �, , HERMANN GÜNTHER GRASSMANN, , 冮 a(t) dt � 冮 (6ti � j � 2k) dt � 3t i � tj � 2tk � C, 2, , Letting t � 0 in this expression and using the initial condition v(0) � i � 2k, we obtain, , (1809–1877), A productive scholar whose work spanned, mathematics, linguistics, theology, and, botany, Hermann Günther Grassmann did, not focus his attention on mathematics, until the age of 31. As a student at the University of Berlin, he took courses in theology, classical languages, and literature, but, he appears not to have taken any courses, in mathematics or physics. After completing his university studies in 1830, Grassmann spent a year undertaking research in, mathematics and preparing himself to, teach in gymnasiums (secondary schools)., He did not do well on the exams and was, qualified to teach only at the lower levels., However, during this time he had made significant mathematical discoveries that, would eventually appear in his 1844 work, Die Lineale Ausdehnungslehre. This was a, truly groundbreaking work. In it he introduced many concepts and techniques that, are of central importance in contemporary, mathematics, such as n-dimensional vector, spaces and multilinear algebra. However,, this work was far ahead of its time, and, Grassmann’s writing style was not clear or, well polished. The mathematical community dismissed Die Lineale Ausdehnungslehre. In spite of this, Grassmann continued to work on his ideas about geometric, calculus and republished the paper in 1862., Still not understood by others, he turned, to studies in linguistics and other areas of, science. Before his death in 1877 he had, written a third version of his paper. It was, published after his death, and it was then, that Grassmann’s discoveries were recognized. Today, Grassmann is credited with, the invention of linear algebra., , v(0) � C � i � 2k, Therefore, the velocity of the object at any time t is, v(t) � (3t 2 i � tj � 2tk) � i � 2k, � (3t 2 � 1)i � tj � 2(t � 1)k, Next, integrating the equation r¿(t) � v(t) with respect to t gives, r(t) �, , 冮 v(t) dt � 冮 [(3t, , 2, , � 1)i � tj � 2(t � 1)k] dt, , � (t 3 � t)i �, , 1 2, t j � (t 2 � 2t)k � D, 2, , Letting t � 0 in r(t) and using the initial condition r(0) � i � 2j � k, we have, r(0) � D � i � 2j � k, Therefore, the position of the object at any time t is, r(t) � (t 3 � t)i �, , 1 2, t j � (t 2 � 2t)k � (i � 2j � k), 2, , 1, � (t 3 � t � 1)i � a t 2 � 2bj � (t 2 � 2t � 1)k, 2, 1, � (t 3 � t � 1)i � a t 2 � 2bj � (t � 1)2 k, 2, , Motion of a Projectile, A projectile of mass m is fired from a height h with an initial velocity v0 and an angle, of elevation a. If we describe the position of the projectile at any time t by the position vector r(t), then its initial position may be described by the vector, r(0) � hj, and its initial velocity by the vector, v(0) � v0 � (√0 cos a)i � (√0 sin a)j, (See Figure 5.), , √0 � 冟 v0 冟, , (1)

Page 31 :

1014, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, y, , v0 � (√0 cos å)i � (√0 sin å)j, , √0 sin å, , å, , FIGURE 5, The initial position of the projectile, is r(0) � hj, and its initial velocity, is v0 � (√0 cos a)i � (√0 sin a)j., , h, , �mgj, , r(t), , √0 cos å, , r(0) � hj, x, , 0, , If we assume that air resistance is negligible and that the only external force acting on the projectile is due to gravity, then the force acting on the projectile during its, flight is, F � �mtj, where t is the acceleration due to gravity (32 ft/sec2 or 9.8 m/sec2). By Newton’s, Second Law of Motion this force is equal to ma, where a is the acceleration of the projectile. Therefore,, ma � �mtj, giving the acceleration of the projectile as, a(t) � �tj, To find the velocity of the projectile at any time t, we integrate the last equation with, respect to t to obtain, v(t) �, , 冮 �tj dt � �ttj � C, , Setting t � 0 and using the initial condition v(0) � v0, we obtain, v(0) � C � v0, Therefore, the velocity of the projectile at any time t is, v(t) � �ttj � v0, Integrating this equation then gives, r(t) �, , 冮 (�ttj � v ) dt � �2 tt j � v t � D, 1, , 2, , 0, , 0, , Setting t � 0 and using the initial condition r(0) � hj, we obtain, r(0) � D � hj, Therefore, the position of the projectile at any time t is, 1, r(t) � � tt 2 j � v0t � hj, 2, or, upon using Equation (1),, 1, r(t) � � tt 2 j � [(√0 cos a)i � (√0 sin a)j]t � hj, 2, � (√0 cos a)ti � ch � (√0 sin a)t �, , 1 2, tt d j, 2

Page 32 :

12.4, , Velocity and Acceleration, , 1015, , DEFINITION Position Function for a Projectile, The trajectory of a projectile fired from a height h with an initial speed √0 and, an angle of elevation a is given by the position vector function, r(t) � (√0 cos a)ti � ch � (√0 sin a)t �, , 1 2, tt d j, 2, , (2), , where t is the constant of acceleration due to gravity., , EXAMPLE 5 Motion of a Projectile A shell is fired from a gun located on a hill, 100 m above a level terrain. The muzzle speed of the gun is 500 m/sec, and its angle, of elevation is 30°., a. Find the range of the shell., b. What is the maximum height attained by the shell?, c. What is the speed of the shell at impact?, Solution Using Equation (2) with h � 100, √0 � 500, a � 30°, and t � 9.8, we see, that the position of the shell at any time t is given by, r(t) � (500 cos 30°)ti � [100 � (500 sin 30°)t � 4.9t 2]j, � 25013ti � (100 � 250t � 4.9t 2)j, The corresponding parametric equations are, x � 25013t, , and, , y � 100 � 250t � 4.9t 2, , a. We first find the time when the shell strikes the ground by solving the equation, 4.9t 2 � 250t � 100 � 0, obtained by setting y � 0. Using the quadratic formula, we have, t�, , 250 � 162,500 � 1960, ⬇ 51.4, 9.8, , We reject the, negative root., , or 51.4 sec. Substituting this value of t into the expression for x we find that the, range of the shell is approximately, 25013 (51.4) ⬇ 22,257, or 22,257 m., b. The height of the shell at any time t is given by, y � 100 � 250t � 4.9t 2, To find the maximum value of y, we solve, y¿ � 250 � 9.8t � 0, to obtain t ⬇ 25.5. Since y⬙ � �9.8 0, the Second Derivative Test implies that, at approximately 25.5 sec into flight, the shell attains its maximum height, y`, or 3289 m., , ⬇ 100 � 250(25.5) � 4.9(25.5) 2 ⬇ 3289, t⬇25.5

Page 33 :

1016, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , c. By differentiating the position function, r(t) � 25013ti � (100 � 250t � 4.9t 2)j, we obtain the velocity of the shell at any time t. Thus,, , y (m), , v(t) � r¿(t) � 25013i � (250 � 9.8t)j, , 3500, 3000, 2500, , From part (a) we know that the time of impact is t ⬇ 51.4. So at the time of, impact the velocity of the shell is, , 2000, 1500, 1000, , v(51.4) ⬇ 25013i � [250 � 9.8(51.4)] j, � 25013i � 253.7j, , 500, 0, , 5,000 10,000 15,000 20,000 x (m), , FIGURE 6, The trajectory of the shell, , 12.4, , Therefore, its speed at impact is, 冟 v(51.4) 冟 � 2(250 13)2 � (253.7)2 ⬇ 502, or 502 m/sec. The trajectory of the shell is shown in Figure 6., , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, , 1. a. What are the velocity, acceleration, and speed of an, object with position vector r(t)?, b. Give the expressions for the quantities in part (a) if the, position vector has the form r(t) � f(t)i � t(t)j � h(t)k., , 12.4, , 2. A projectile of mass m is fired from a height h with an initial velocity v0 and an angle of elevation a. Write a vector, representing, a. Its initial position., b. Its initial velocity in terms of √0 � 冟 v0 冟 and a., c. Its velocity at time t., d. Its position at time t., , EXERCISES, , In Exercises 1–6, find the velocity, acceleration, and speed of an, object with the position function for the given value of t. Sketch, the path of the object and its velocity and acceleration vectors., 1. r(t) � ti � (4 � t 2)j;, 2. r(t) � 具t 2 � 4, 2t典;, , t�1, , t�1, , 3. r(t) � cos ti � 3 sin tj;, �t, , 4. r(t) � e i � e j;, t, , 6. r(t) � 具t, t , t 典;, 2, , 3, , p, 2, , t�1, , 7. r(t) � ti � t j � (t � 4)k, 8. r(t) � 具1t, 1 � 1t, t典, 1, 9. r(t) � ti � t 2 j � k, t, , v(0) � i � 2j,, , 14. a(t) � 2i � tk,, , t�0, , 2, , 12. r(t) � t cos ti � t sin tj � t 2 k, , 13. a(t) � �32k,, , In Exercises 7–12, find the velocity, acceleration, and speed of, an object with the given position vector., 2, , 11. r(t) � et具cos t, sin t, 1典, , In Exercises 13–18, find the velocity and position vectors of an, object with the given acceleration, initial velocity, and position., , p, t�, 4, , 5. r(t) � cos ti � sin tj � tk; t �, , 10. r(t) � et i � e�t j � t 2 k, , v(0) � k,, , 15. a(t) � i � tj � (1 � t)k,, 16. a(t) � 具et, 0, e�t典,, , r(0) � 128k, , r(0) � 0, v(0) � i � k, r(0) � j � k, , v(0) � 具1, 2, 0典,, , 17. a(t) � �cos ti � sin tj � k,, , r(0) � 具3, 1, 2典, , v(0) � 2k, r(0) � i, , 18. a(t) � 具cosh t, sinh t, 0典, v(0) � 具0, 1, 1典, r(0) � 具1, 0, 0典, 19. An object moves with a constant speed. Show that the, velocity and acceleration vectors associated with this motion, are orthogonal., Hint: Study Example 5 in Section 12.2., , 20. Suppose that the acceleration of a moving object is always, 0. Show that its motion is rectilinear (that is, along a straight, line)., , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login.

Page 34 :

12.4, 21. A particle moves in three-dimensional space in such a way, that its velocity is always orthogonal to its position vector., Show that its trajectory lies on a sphere centered at the, origin., , 1017, , Velocity and Acceleration, , √0 ft/sec, determine the range of values of √0 that will allow, the man to land on the net. Neglect air resistance., y, , 22. A particle moves in three-dimensional space in such a way, that its velocity is always parallel to its position vector., Show that its trajectory lies on a straight line passing, through the origin., 23. Motion of a Projectile A projectile is fired from ground level, with an initial speed of 1500 ft/sec and an angle of elevation, of 30°., a. Find the range of the projectile., b. What is the maximum height attained by the projectile?, c. What is the speed of the projectile at impact?, 24. Motion of a Projectile Rework Exercise 23 if the projectile is, fired with an angle of elevation of 60°., , 60°, 0, , x, 150 ft, , 32. Cycloid Motion A particle of charge Q is released at rest from, the origin in a region of uniform electric and magnetic fields, described by E � Ek and B � Bi., z, , 25. Motion of a Projectile Rework Exercise 23 if the projectile, is fired with an angle of elevation of 30° from a height of, 200 ft above a level terrain., , E � Ek, , 26. Motion of a Projectile A shell is fired from a gun situated on, a hill 500 ft above level ground. If the angle of elevation, of the gun is 0° and the muzzle speed of the shell is, 2000 ft/sec, when and where will the shell strike the, ground?, 27. Motion of a Projectile A mortar shell is fired with a muzzle, speed of 500 ft/sec. Find the angle of elevation of the mortar, if the shell strikes a target located 1200 ft away., 28. Path of a Baseball A baseball player throws a ball at an angle, of 45° with the horizontal. If the ball lands 250 ft away,, what is the initial speed of the ball? (Ignore the height of, the player.), 29. An object moves in a circular path described by the position, vector, r(t) � a cos vti � a sin vtj, where v � du>dt is the constant angular velocity of the, object., a. Find the velocity vector, and show that it is orthogonal, to r(t)., b. Find the acceleration vector, and show that it always, points toward the center of the circle., c. Find the speed and the magnitude of the acceleration, vector of the object., 30. An object located at the origin is to be projected at an initial, speed of √0 m/sec and an angle of elevation of a so that it, will strike a target located at the point (r, 0). Neglecting air, resistance, find the required angle a., 31. Human Cannonball The following figure shows the trajectory, of a “human cannonball” who will be shot out of a cannon, located at ground level onto a net. If the angle of elevation, of the cannon is 60° and the initial speed of the man is, , 30 ft, , 0, y, , B � Bi, x, , a. Use the Lorentz Force Law, F � Q[E � (v B)] where, v is the velocity of the particle, to show that, F � QB, , dy, dz, j � QaE � B bk, dt, dt, , b. Use the result of part (a) and Newton’s Second Law of, Motion to show that the equations of motion of the particle take the form, d 2x, dt, , 2, , d 2y, , �0, , dt, , 2, , �v, , dz, dt, , d 2z, dt 2, , � va, , dy, E, � b, B, dt, , QB, and m is the mass of the particle., m, c. Show that the general solution of the system in part (b), is x(t) � C1t � C2, y(t) � C3 cos vt � C4 sin vt �, (E>B)t � C5, and z(t) � C4 cos vt � C3 sin vt � C6., d. Use the initial conditions, where v �, , x(0) �, , dx, (0) � 0,, dt, and, , z(0) �, , y(0) �, , dy, (0) � 0,, dt, , dz, (0) � 0, dt, , to determine C1, C2, p , C6 and hence show that the, trajectory of the particle is the cycloid x(t) � 0, y(t) �, (E>(vB))(vt � sin vt), and z(t) � (E(vB))(1 � cos vt)., (See Section 10.2.)

Page 35 :

1018, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , 33. Newton’s Law of Inertia As a model train moves along a, straight track at a constant speed of √0 ft/sec, a ball, bearing is ejected vertically from the train at an initial, speed of √1 ft/sec. Show that at some later time the ball, bearing will return to the location on the train from which, it was released., , 36. Motion of a Projectile Suppose that a projectile is fired from, the origin of a two-dimensional coordinate system at an, angle of elevation of a and an initial speed of √0., a. Show that the position function r(t) of the projectile is, equivalent to the parametric equations x(t) � (√0 cos a)t, and y(t) � (√0 sin a)t � (1>2)tt 2., b. Eliminate t in the equations in part (a) to find an equation in x and y describing the trajectory of the projectile., What is the shape of the trajectory?, , Note: This experiment demonstrates Newton’s Law of Inertia., , 34. Let r(t) be the position vector of a moving particle and let, r(t) � 冟 r(t) 冟., a. Show that r ⴢ r¿ � rr¿., b. What can you say about the orbit of the particle if v � r¿, is perpendicular to r?, c. What can you say about the relationship between the, velocity vector and the position vector of the particle if, the orbit is circular?, , In Exercises 37–38, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why. If it is false, explain why or give, an example to show that it is false., 37. If r(t) gives the position of a particle at time t, then, r¿(t) � 冟 r¿(t) 冟T(t), where T(t) is the unit tangent vector, to the curve described by r at t and r¿(t) 0., , 35. A particle has position given by r(t) � 具t, t 2, t 3典 at time t for, 0 � t � 1. At time t � 1 the particle departs the curve and, flies off along the line tangent to the curve at r(1). If the, particle maintains a constant speed given by 冟 v(1) 冟, what is, the trajectory of the particle for t � 1? What is its position, at t � 2?, , 12.5, , 38. If a particle moves in such a way that its speed is always, constant, then its acceleration is zero., , Tangential and Normal Components of Acceleration, The Unit Normal, Suppose that C is a smooth space curve described by the vector function r(t). Then,, as we saw earlier,, , z, , N(t), , T(t) �, , C, T(t), , r(t), 0, y, x, , FIGURE 1, At each point on the curve C, the unit, normal vector N(t) is orthogonal to, T(t) and points in the direction the, curve is turning., , r¿(t), 冟 r¿(t) 冟, , r¿(t), , 0, , is the unit tangent vector to the curve C at the point corresponding to t. Since 冟 T(t) 冟 � 1, for every t, the result of Example 5 in Section 12.2 tells us that the vector T¿(t) is, orthogonal to T(t). Therefore, if r¿ is also smooth, we can normalize T¿(t) to obtain a, unit vector that is orthogonal to T(t). This vector, N(t) �, , T¿(t), 冟 T¿(t) 冟, , is called the principal unit normal vector (or simply the unit normal) to the curve, C at the point corresponding to t. (See Figure 1.), , EXAMPLE 1 Let C be the helix defined by, r(t) � 2 cos ti � 2 sin tj � tk, , t�0, , Find T(t) and N(t). Sketch C and the vectors T(p>2) and N(p>2)., Solution, , Since, r¿(t) � �2 sin ti � 2 cos tj � k, , and, 冟 r¿(t) 冟 � 24 sin2 t � 4 cos2 t � 1 � 15

Page 36 :

12.5, , Tangential and Normal Components of Acceleration, , 1019, , we have, T(t) �, , r¿(t), 1, �, (�2 sin ti � 2 cos tj � k), 冟 r¿(t) 冟, 15, , Next, differentiating T, we obtain, T¿(t) �, , 1, 2, (�2 cos ti � 2 sin tj) � �, (cos ti � sin tj), 15, 15, , Since, 2, 2, 2 cos2 t � sin2 t �, 15, 15, , 冟 T¿(t) 冟 �, it follows that, N(t) �, z, , T¿(t), � �(cos ti � sin tj), 冟 T¿(t) 冟, , In particular, at t � p>2 we have, , π, N __, 2, , (), , p, 1, 2, 1, Ta b �, (�2 sin ti � 2 cos tj � k) `, ��, i�, k, 2, 15, 15, 15, t�p>2, , π, T __, 2, , (), and, , p, Na b � �(cos ti � sin tj) `, � �j, 2, t�p>2, C, y, x, , FIGURE 2, The unit vectors T(p>2) and, N(p>2) at the point 1 0, 2, p2 2, on the helix, , The curve C and the unit vectors T(p>2) and N(p>2) are shown in Figure 2. Note, that, in general, the principal normal vector N(t) is parallel to the xy-plane and points, toward the z-axis., , Tangential and Normal Components of Acceleration, Let’s return to the study of the motion of an object moving along the curve C described, by the vector function r defined on the parameter interval I. Recall that the speed √ of, the object at any time t is √ � 冟 v(t) 冟 � 冟 r¿(t) 冟. But, T�, , r¿(t), 冟 r¿(t) 冟, , so we can write, v(t) � r¿(t) � 冟 r¿(t) 冟 T � √T, , (1), , which expresses the velocity of the object in terms of its speed and direction. (See, Figure 3.), z, √, v(t) � √T, T, r(t), , FIGURE 3, The velocity of the object, at time t is v(t) � √T., , 0, [, a, , t, , ], b, , t, , y, x

Page 37 :

1020, , Chapter 12 Vector-Valued Functions, , The acceleration of the object at time t is, a � v¿ �, , d, (√T) � √¿T � √T¿, dt, , To obtain an expression for T¿, recall that, N�, , T¿, 冟 T¿ 冟, , so T¿ � 冟 T¿ 冟 N. Now we need an expression for 冟 T¿ 冟. But from Equation (4) in Section, 12.3 we have, 冟 T¿ 冟, k�, 冟 r¿ 冟, where k is the curvature of C. This gives, 冟 T¿ 冟 � k冟 r¿ 冟 � k√, so T¿ � 冟 T¿ 冟 N � k√N., Therefore,, a � √¿T � √(k√N), , z, , a, , aN, , N, T, , aT, , 0, x, , � √¿T � k√2 N, , C, , y, , FIGURE 4, The acceleration a has a component, aTT in the tangential direction and, a component aNN in the normal, direction., , (2), , This result shows that the acceleration vector a can be resolved into the sum of two, vectors—one along the tangential direction and the other along the normal direction., The magnitude of the acceleration along the tangential direction is called the tangential scalar component of acceleration and is denoted by aT, whereas the magnitude, of the acceleration along the normal direction is called the normal scalar component, of acceleration and is denoted by aN. Thus,, a � aTT � aNN, , (3), , where, aT � √¿, , and, , aN � k√2, , (4), , (See Figure 4.), The following theorem gives formulas for calculating aT and aN directly from r and, its derivatives., , THEOREM 1 Tangential and Normal Components of Acceleration, Let r(t) be the position vector of an object moving along a smooth curve C., Then, a � aTT � aNN, where, aT �, , r¿(t) ⴢ r⬙(t), 冟 r¿(t) 冟, , and, , aN �, , 冟 r¿(t) r⬙(t) 冟, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, , PROOF If we take the dot product of v and a as given by Equations (1) and (2), we, obtain, v ⴢ a � (√T) ⴢ (√¿T � k√2 N), � √√¿T ⴢ T � k√3 T ⴢ N

Page 38 :

12.5, , Tangential and Normal Components of Acceleration, , 1021, , But T ⴢ T � 冟 T 冟2 � 1, since T is a unit vector, and T ⴢ N � 0, since T and N are orthogonal. Therefore,, v ⴢ a � √√¿, or, in view of Equation (4),, aT � √¿ �, , r¿(t) ⴢ r⬙(t), vⴢa, �, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, √, , Next, using Equation (4) and the formula for curvature (Theorem 2 in Section 12.3),, we have, aN � k√2 �, , 冟 r¿(t), , 冟 r¿(t) r⬙(t) 冟, r⬙(t) 冟, 冟 r¿(t) 冟2 �, 3, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, , EXAMPLE 2 A particle moves along a curve described by the vector function, r(t) � ti � t 2 j � t 3 k. Find the tangential scalar and normal scalar components of, acceleration of the particle at any time t., Solution, , We begin by computing, r¿(t) � i � 2tj � 3t 2 k, r⬙(t) � 2j � 6tk, , Then, using Theorem 1, we obtain, aT �, , r¿(t) ⴢ r⬙(t), 4t � 18t 3, �, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, 21 � 4t 2 � 9t 4, , Next, we compute, r¿(t), , i, r⬙(t) � † 1, 0, , j, 2t, 2, , k, 3t 2 † � 6t 2 i � 6tj � 2k, 6t, , Then, using Theorem 1, we have, aN �, , 冟 r¿(t) r⬙(t) 冟, 236t 4 � 36t 2 � 4, 9t 4 � 9t 2 � 1, �, 2, �, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, B 9t 4 � 4t 2 � 1, 21 � 4t 2 � 9t 4, , EXAMPLE 3 Motion of a Projectile, tion function of a shell is given by, , Refer to Example 5 in Section 12.4. The posi-, , r(t) � 250 13ti � (100 � 250t � 4.9t 2)j, a. Find the tangential and normal scalar components of acceleration of the shell at, any time t., b. Find aT(t) and aN (t) for t � 0, 12.75, 25.5, and 38.25., c. Is the shell accelerating or decelerating in the tangential direction at the values of, t specified in part (b)?, Solution, a. r¿(t) � 250 13i � (250 � 9.8t)j, r⬙(t) � �9.8j

Page 39 :