Page 1 :

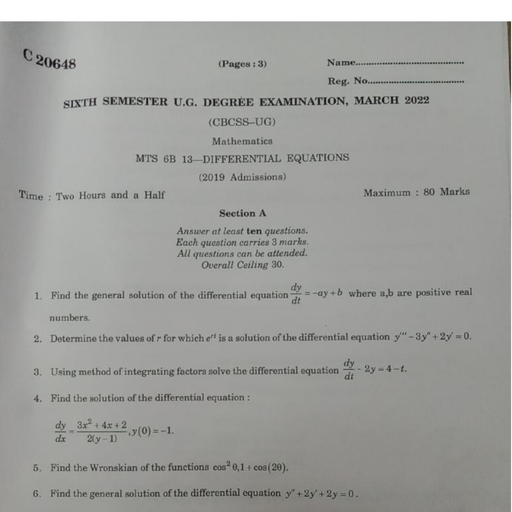

848, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, , In Exercises 109–114, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why it is true. If it is false, give an, example to show why it is false., , 112. The asymptotes of the hyperbola x 2>a 2 � y 2>b 2 � 1 are, perpendicular to each other if and only if a � b., 113. If A and C are both positive constants, then, , 109. The graph of 2x 2 � y 2 � F � 0 is a hyperbola, provided, that F 0., , Ax 2 � Cy 2 � Dx � Ey � F � 0, is an ellipse., , 110. The graph of y 4 � 16ax 2, where a � 0, is a parabola., 111. The ellipse b x � a y � a b , where a � b � 0, is, contained in the circle x 2 � y 2 � a 2 and contains the, circle x 2 � y 2 � b 2., 2 2, , 10.2, , 2 2, , 2 2, , 114. If A and C have opposite signs, then, Ax 2 � Cy 2 � Dx � Ey � F � 0, is a hyperbola., , Plane Curves and Parametric Equations, Why We Use Parametric Equations, Figure 1a gives a bird’s-eye view of a proposed training course for a yacht. In Figure 1b, we have introduced an xy-coordinate system in the plane to describe the position of, the yacht. With respect to this coordinate system the position of the yacht is given, by the point P(x, y), and the course itself is the graph of the rectangular equation, 4x 4 � 4x 2 � y 2 � 0, which is called a lemniscate. But representing the lemniscate in, terms of a rectangular equation in this instance has three major drawbacks., y (mi), 1, P(x, y), �1, , 1, , x (mi), , �1, , FIGURE 1, , (a) The dots give the position of markers., , (b) An equation of the curve C is 4x4 � 4x 2 � y 2 � 0., , First, the equation does not define y explicitly as a function of x or x as a function, of y. You can also convince yourself that this is not the graph of a function by applying the vertical and horizontal line tests to the curve in Figure 1b (see Section 0.2)., Because of this, we cannot make direct use of many of the results for functions developed earlier. Second, the equation does not tell us when the yacht is at a given point, (x, y). Third, the equation gives no inkling as to the direction of motion of the yacht., To overcome these drawbacks when we consider the motion of an object in the, plane or plane curves that are not graphs of functions, we turn to the following representation. If (x, y) is a point on a curve in the xy-plane, we write, x � f(t), , y � t(t), , where f and t are functions of an auxiliary variable t with (common) domain some, interval I. These equations are called parametric equations, t is called a parameter,, and the interval I is called a parameter interval.

Page 2 :

849, , 10.2 Plane Curves and Parametric Equations, , If we think of t on the closed interval [a, b] as representing time, then we can interpret the parametric equations in terms of the motion of a particle as follows: At t � a, the particle is at the initial point ( f(a), t(a)) of the curve or trajectory C. As t increases, from t � a to t � b, the particle traverses the curve in a specific direction called the, orientation of the curve, eventually ending up at the terminal point ( f(b), t(b)) of, the curve. (See Figure 2.), y, , ( f(b), g(b)), , C, ( f(a), g(a)), ( f(t), g(t)), , FIGURE 2, As t increases from a to b, the particle, traces the curve from ( f(a), t(a)) to, ( f(b), t(b)) in a specific direction., , a, , t, , t, , b, , x, , 0, , Parameter interval is [a, b]., , We can also interpret the parametric equations in geometric terms as follows: We, take the line segment [a, b] and, by a process of stretching, bending, and twisting, make, it conform geometrically to the curve C., , Sketching Curves Defined by Parametric Equations, Before looking at some examples, let’s define the following term., , DEFINITION Plane Curve, A plane curve is a set C of ordered pairs (x, y) defined by the parametric equations, x � f(t), , and, , y � t(t), , where f and t are continuous functions on a parameter interval I., , EXAMPLE 1 Sketch the curve described by the parametric equations, x � t2 � 4, , and, , y � 2t, , �1, , t, , 2, , Solution By plotting and connecting the points (x, y) for selected values of t (Table 1),, we obtain the curve shown in Figure 3., TABLE 1, t, (x, y), , �1, , (�3, �2), , 1, , �12, , �154,, , �1 2, , 0, , (�4, 0), , 1, , 1, 2, , �154,, , 12, , 1, , 2, , (�3, 2), , (0, 4)

Page 3 :

850, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, y, , C, , �1 0 1 2, , FIGURE 3, As t increases from �1 to 2, the curve, C is traced from the initial point, (�3, �2) to the terminal point (0, 4)., , (0, 4), , 4, 3, 2, 1, , �3�2, , t, , x, , �1, �2, (�3, �2), �3, , Alternative Solution We eliminate the parameter t by solving the second of the two, given parametric equations for t, obtaining t � 12 y. We then substitute this value of t, into the first equation to obtain, 1 2, x � a yb � 4, 2, , x�, , or, , 1 2, y �4, 4, , This is an equation of a parabola that has the x-axis as its axis of symmetry and its, vertex at (�4, 0). Now observe that t � �1 gives (�3, �2) as the initial point of the, curve and that t � 2 gives (0, 4) as the terminal point of the curve. So tracing the graph, from the initial point to the terminal point gives the desired curve, as obtained earlier., , We will adopt the convention here, just as we did with the domain of a function,, that the parameter interval for x � f(t) and y � t(t) will consist of all values of t for, which f(t) and t(t) are real numbers, unless otherwise noted., , EXAMPLE 2 Sketch the curves represented by, a. x � 1t and y � t, b. x � t and y � t 2, Solution, a. We eliminate the parameter t by squaring the first equation to obtain x 2 � t. Substituting this value of t into the second equation, we obtain y � x 2, which is an, equation of a parabola. But note that the first parametric equation implies that, t � 0, so x � 0. Therefore, the desired curve is the right portion of the parabola, shown in Figure 4. Finally, note that the parameter interval is [0, ⬁) , and as t, increases from 0, the desired curve starts at the initial point (0, 0) and moves, away from it along the parabola., y, , FIGURE 4, As t increases from 0, the curve, starts out at (0, 0) and follows, the right portion of the parabola, with indicated orientation., , 4, 3, 2, 1, 0, , t, , t, , Parameter interval is [0, �)., , (t � 0), , (t � 4), , (t � 1), 1 2, , x, , t, , (x, y), , 0, 1, 2, 4, , (0, 0), (1, 1), ( 12, 2), (2, 4)

Page 4 :

10.2 Plane Curves and Parametric Equations, , 851, , b. Substituting the first equation into the second yields y � x 2. Although the rectangular equation is the same as that in part (a), the curve described by the parametric equations here is different from that of part (a), as we will now see. In this, instance the parameter interval is (�⬁, ⬁). Furthermore, as t increases from �⬁, to ⬁ , the curve runs along the parabola y � x 2 from left to right, as you can see, by plotting the points corresponding to, say, t � �1, 0, and 1. You can also see, this by examining the parametric equation x � t, which tells us that x increases as, t increases. (See Figure 5.), , y, , FIGURE 5, As t increases from �⬁ to ⬁ ,, the entire parabola is traced, out, from left to right., , 4, 3, 2, (t � �1) 1, t, , 0, , (t � 0), , (t � 1), 1 2, , x, , t, , (x, y), , �1, 0, 1, , (�1, 1), (0, 0), (1, 1), , Parameter interval is (��, �)., , For problems involving motion, it is natural to use the parameter t to represent time., But other situations call for different representations or interpretations of the parameters, as the next two examples show. Here, we use an angle as a parameter., , EXAMPLE 3 Describe the curves represented by the parametric equations, x � a cos u, , and, , y � a sin u, , a�0, , with parameter intervals, a. [0, p], b. [0, 2p], c. [0, 4p], Solution, , We have cos u � x>a and sin u � y>a. So, y 2, x 2, 1 � cos2 u � sin2 u � a b � a b, a, a, , giving us, x 2 � y2 � a2, This tells us that each of the curves under consideration is contained in a circle of, radius a, centered at the origin., a. If u � 0, then x � a and y � 0, giving (a, 0) as the initial point on the curve. As, u increases from 0 to p, the required curve is traced out in a counterclockwise, direction, terminating at the point (�a, 0). (See Figure 6a.), b. Here, the curve is a complete circle that is traced out in a counterclockwise direction, starting at (a, 0) and terminating at the same point (see Figure 6b)., c. The curve here is a circle that is traced out twice in a counterclockwise direction, starting at (a, 0) and terminating at the same point (see Figure 6c).

Page 5 :

852, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, y, , (¨ � π), 0, , Historical Biography, , ¨, , π, , ¨, , �a, , (¨ � 0), a, , x, , (a), , Science Source/, Photo Researchers, Inc., , y, , ¨, 0, , ¨, , 2π, , �a, , (¨ � 0, 2π), x, , a, , (b), y, , MARIA GAËTANA AGNESI, (1718–1799), Maria Gaetana Agnesi’s exceptional academic talents surfaced at an early age, and, her wealthy father provided her with the, best tutors. By the age of nine, she had, learned many languages in addition to her, native Italian, including Greek and Hebrew., At that same age, she translated into Latin, an article her tutor had written in Italian, defending higher education for women. She, then delivered it, from memory, to one of, the gatherings of intellectuals her father, hosted in their home. Agnesi developed a, deep interest in Newtonian physics, but her, primary interests became religion and, mathematics. After Agnesi wrote a book on, differential calculus, her talents attracted, the attention of Pope Benedict XIV, who, appointed her to a position at the University of Bologna. Despite being offered the, chair of mathematics at Bologna, Agnesi, left the academic world in 1752 so that she, could fulfill a desire to serve others. She, devoted the rest of her life to religious, charitable projects, including running a, home for the poor., Later, in Exercises 10.2, you will learn, that the curve in Problem 41 is called the, witch of Agnesi. Why was this given such, a peculiar name? It is actually because of a, mistranslation of Maria Agnesi’s 1748 work, Instituzione analitiche ad uso della, gioventu italiana. In her discussion of the, curve represented by the rectangular, equation y(x2 � a2) � a3, Agnesi used, the Italian word versiera, which is derived, from the Latin vertere, meaning “to turn.”, However, this word was confused with, avversiera, meaning “witch” or “devil’s, wife,” and the curve became known as the, witch of Agnesi., , ¨, 4π ¨, , 0, , �a, , (¨ � 0, 2π, 4π), x, , a, , (c), Parameter interval, , FIGURE 6, The curve is (a) a semicircle, (b) a complete circle, and (c) a complete circle traced out twice., All curves are traced in a counterclockwise direction., , EXAMPLE 4 Describe the curve represented by, x � 4 cos u, Solution, , and, , y � 3 sin u, , 0, , u, , 2p, , Solving the first equation for cos u and the second equation for sin u gives, cos u �, , x, 4, , sin u �, , y, 3, , and, , Squaring each equation and adding the resulting equations, we obtain, y 2, x 2, cos2 u � sin2 u � a b � a b, 4, 3, Since cos2 u � sin2 u � 1, we end up with the rectangular equation, y2, x2, �, �1, 16, 9, From this we see that the curve is contained in an ellipse centered at the origin. If, u � 0, then x � 4 and y � 0, giving (4, 0) as the initial point of the curve. As u increases, from 0 to 2p, the elliptical curve is traced out in a counterclockwise direction, terminating at (4, 0) . (See Figure 7.)

Page 6 :

10.2 Plane Curves and Parametric Equations, y, , 853, , (¨ � π2 ), , 2, 1, , (¨ � π), , FIGURE 7, As u increases from 0 to 2p,, the curve that is traced out in, a counterclockwise direction, beginning and ending at, (4, 0) is an ellipse., , �4 �3 �2 �1 0, �1, , 1, , 2, , (¨ � 0, 2π), x, 4, , 3, , �2, , (¨ � 3π2 ), EXAMPLE 5 A proposed training course for a yacht is represented by the parametric equations, x � sin t, , y � sin 2t, , and, , 0, , t, , 2p, , where x and y are measured in miles., a. Show that the rectangular equation of the course is 4x 4 � 4x 2 � y 2 � 0., b. Describe the course., Solution, a. Using the trigonometric identity sin 2t � 2 sin t cos t, we rewrite the second of, the parametric equations in the form, y � 2 sin t cos t � 2x cos t, , Since x � sin t, , Solving for cos t, we have, cos t �, , y, 2x, , Then, using the identity sin2 t � cos2 t � 1, we obtain, x2 � a, , y 2, b �1, 2x, , x2 �, , y2, 4x 2, , �1, , or, 4x 4 � 4x 2 � y 2 � 0, b. From the results of part (a) we see that the required curve is symmetric with, respect to the x-axis, the y-axis, and the origin. Therefore, it suffices to concentrate first on drawing the part of the curve that lies in the first quadrant and then, make use of symmetry to complete the curve. Since both sin t and sin 2t are nonnegative only for 0 t p2 , we first sketch the curve corresponding to values of t, in C0, p2 D . With the help of the following table we obtain the curve shown in Figure 8. The direction of the yacht is indicated by the arrows., t, , 0, , (x, y), , (0, 0), , p, 6, , 1 12, 132 2, , p, 4, , 1 122, 1 2, , p, 3, , 1 132, 132 2, , p, 2, , (1, 0)

Page 7 :

854, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, y (mi), 1, , �1, , π, t�, (t � π6 ) ( 4 ) π, (t � 3 ), (t � π2 ), (t � 0), 1, , x (mi), , �1, , FIGURE 8, The training course for the yacht, , EXAMPLE 6 Cycloids Let P be a fixed point on the rim of a wheel. If the wheel is, allowed to roll along a straight line without slipping, then the point P traces out a curve, called a cycloid (see Figure 9). Suppose that the wheel has radius a and rolls along the, x-axis. Find parametric equations for the cycloid., FIGURE 9, The cycloid is the curve, traced out by a fixed point P, on the rim of a rolling wheel., y, , P, a, , Solution Suppose that the wheel rolls in a positive direction with the point P initially, at the origin of the coordinate system. Figure 10 shows the position of the wheel after, it has rotated through u radians. Because there is no slippage, the distance the wheel, has rolled from the origin is, , C(a¨, a), ¨ a cos ¨, a sin ¨, a, , P, y, , d(O, M) � length of arc PM � au, , O, M, , x, , x, , giving its center as C(au, a). Also, from Figure 10 we see that the coordinates of P(x, y), satisfy, x � d(O, M) � a sin u � au � a sin u � a(u � sin u), , a¨, , FIGURE 10, The position of the wheel after it has, rotated through u radians, , and, y � d(C, M) � a cos u � a � a cos u � a(1 � cos u), Although these results are derived under the tacit assumption that 0 � u � p2 , it can, be demonstrated that they are valid for other values of u. Therefore, the required parametric equations of the cycloid are, x � a(u � sin u), , and, , y � a(1 � cos u), , �⬁ � u � ⬁, , The cycloid provides the solution to two famous problems in mathematics:, 1. The brachistochrone problem: Find the curve along which a moving particle, (under the influence of gravity) will slide from a point A to another point B,, not directly beneath A, in the shortest time (see Figure 11a)., 2. The tautochrone problem: Find the curve having the property that it takes the, same time for a particle to slide to the bottom of the curve no matter where the, particle is placed on the curve (see Figure 11b)., The brachistochrone problem—the problem of finding the curve of quickest, descent—was advanced in 1696 by the Swiss mathematician Johann Bernoulli. Offhand, one might conjecture that such a curve should be a straight line, since it yields

Page 8 :

10.2 Plane Curves and Parametric Equations, , 855, , A, , FIGURE 11, The cycloid provides the solution, to both the brachistochrone, and the tautochrone problem., , P, P, , B, , (b) The tautochrone problem, , (a) The brachistochrone problem, , the shortest distance between the two points. But the velocity of the particle moving, on the straight line will build up comparatively slowly, whereas if we take a curve that, is steeper near A, even though the path becomes longer, the particle will cover a large, portion of the distance at a greater speed. The problem was solved by Johann Bernoulli,, his older brother Jacob Bernoulli, Leibniz, Newton, and l’Hôpital. They found that the, curve of quickest descent is an inverted arc of a cycloid (Figure 11a). As it turns out,, this same curve is also the solution to the tautochrone problem., , 10.2, , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, , 1. What is a plane curve? Give an example of a plane curve, that is not the graph of a function., 2. What is the difference between the curve C1 with parametric, representation x � cos t and y � sin t, where 0 t 2p,, and the curve C2 with parametric representation x � sin t, and y � cos t, where 0 t 2p?, , 10.2, , EXERCISES, , In Exercises 1–28, (a) find a rectangular equation whose graph, contains the curve C with the given parametric equations, and, (b) sketch the curve C and indicate its orientation., 1. x � 2t � 1,, 2. x � t � 2,, 3. x � 1t,, 4. x � t 2,, , 3. Describe the relationship between the curve C1 with parametric equations x � f(t) and y � t(t), where 0 t 1,, and the curve C2 with parametric equations x � f(1 � t) and, y � t(1 � t), where 0 t 1., , y�t�3, y � 2t � 1; �1, , t, , 5. x � t 2 � 1,, , 0, , t, , y � 2t � 1, , 7. x � t 2,, , y � t 3; �2, , 22. x � t ,, , p, 2, , 1, , t, , y � e2t, y � 3 ln t, , 23. x � ln 2t, y � t 2, , y�t�1, , 9. x � 2 sin u,, , y � 2 cos u;, , 0, , u, , 2p, , 10. x � cos 2u,, , y � 3 sin u;, , 0, , u, , 2p, , 11. x � 2 sin u,, , y � 3 cos u;, , 0, , 13. x � 2 cos u � 2,, , 21. x � �et,, , 2, , 24. x � et,, , y � sin u � 2;, , u, , 20. x � et, y � e�t, , 2, , 1, 8. x � 1 � ,, t, , 12. x � cos u � 1,, , 16. x � sec u, y � cos u, , 3, , t, , u, , y � cos 2u, , 19. x � sin2 u, y � sin4 u; 0, t, , 0, , 18. x � cos3 u, y � sin3 u, , 3, , y � 2t 2 � 1; �2, , 6. x � t 3,, , 15. x � cos u,, , y � 3 cos u � 1;, , 17. x � sec u, y � tan u; �p2 � u � p2, , 5, , y�9�t, y � t � 1;, , 14. x � sin u � 3,, , u, 0, , y � 3 sin u � 1;, , 25. x � cosh t, y � sinh t, , 2p, u, 0, , y � ln t, y � 2 cosh t, , 2, , 27. x � (t � 1) ,, , y � (t � 1)3;, , ,, , 1�t, 1 � t2, , 28. x �, , 2p, u, , 26. x � 3 sinh t,, , 2p, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login., , 2t, 1 � t2, , 2, , y�, , 2, , 2p

Page 9 :

856, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, , In Exercises 29–34, the position of a particle at time t is (x, y)., Describe the motion of the particle as t varies over the time, interval [a, b]., 29. x � t � 1,, , y � 1t;, , 30. x � sin pt,, , y � cos pt;, , 31. x � 1 � cos t,, , [0, 4], [0, 6], , y � 2 � sin t;, , 32. x � 1 � 2 sin 2t,, , [0, 2p], , y � 2 � 4 sin 2t;, , x � ru � d sin u, , [0, 2p], , y � e2t�1; [0, ⬁), , 35. Flight Path of an Aircraft The position (x, y) of an aircraft flying in a fixed direction t seconds after takeoff is given by, x � tan(0.025pt) and y � sec(0.025pt) � 1, where x and y, are measured in miles. Sketch the flight path of the aircraft, for 0 t 403., 36. Trajectory of a Shell A shell is fired from a howitzer with a, muzzle speed of √0 ft/sec. If the angle of elevation of the, howitzer is a, then the position of the shell after t sec is, described by the parametric equations, x � (√0 cos a)t, , y � (√0 sin a)t �, , and, , x � 2a cot u, , and, , y � 2a sin2 u, , y, y � 2a, P(x, y), , (0, a), ¨, , x, , 0, , 42. If a string is unwound from a circle of radius a in such a, way that it is held taut in the plane of the circle, then its end, P will trace a curve called the involute of the circle. Referring to the following figure, show that the parametric equations of the involute are, , 37. Let P1(x 1, y1) and P2 (x 2, y2) be two distinct points in the, plane. Show that the parametric equations, and, , 41. The witch of Agnesi is the curve shown in the following, figure. Show that the parametric equations of this curve are, , 1 2, tt, 2, , where t is the acceleration due to gravity (32 ft/sec2)., a. Find the range of the shell., b. Find the maximum height attained by the shell., c. Show that the trajectory of the shell is a parabola by, eliminating the parameter t., , x � x 1 � (x 2 � x 1)t, , y � r � d cos u, , and, , where u is the same parameter as that for the cycloid., Sketch the trochoid for the cases in which d � r and d � r., , 33. x � sin t, y � sin2 t; [0, 3p], 34. x � e�t,, , rolls without slipping along a straight line is called a trochoid. (The cycloid is the special case of a trochoid with, d � r.) Suppose that the circle rolls along the x-axis in the, positive direction with u � 0 when the point P is at one of, the lowest points on the trochoid. Show that the parametric, equations of the trochoid are, , x � a(cos u � u sin u), , y � a(sin u � u cos u), , and, , y � y1 � (y2 � y1)t, , describe (a) the line passing through P1 and P2 if, �⬁ � t � ⬁ and (b) the line segment joining P1, and P2 if 0 t 1., , y, String, , 38. Show that, x � a cos t � h, , and, , y � b sin t � k, , 0, , t, , P(x, y), , ¨, , 2p, 0, , are parametric equations of an ellipse with center at (h, k), and axes of lengths 2a and 2b., , (a, 0), , x, , 39. Show that, x � a sec t � h, , and, , y � b tan t � k, t 僆 1 �p2 , p2 2 傼, , 1 p2 , 3p2 2, , are parametric equations of a hyperbola with center at (h, k), and transverse and conjugate axes of lengths 2a and 2b,, respectively., 40. Let P be a point located a distance d from the center of a, circle of radius r. The curve traced out by P as the circle, , In Exercises 43–46, use a graphing utility to plot the curve with, the given parametric equations., 43. x � 2 sin 3t,, , y � 3 sin 1.5t;, , t�0, , 44. x � cos t � 5 cos 3t,, , y � 6 cos t � 5 sin 3t;, , 45. x � 2 cos t � cos 2t,, , y � 2 sin t � sin 2t;, , 0, , t, , 2p, , 46. x � 3 cos t � cos 3t,, , y � 3 sin t � sin 3t;, , 0, , t, , 2p, , 0, , t, , 2p

Page 10 :

10.3 The Calculus of Parametric Equations, 47. The butterfly catastrophe curve, which is described by the, parametric equations, x � c(8at 3 � 24t 5), , and, , is the radius of the circle. The prolate cycloid is described, by the parametric equations, , y � c(�6at 2 � 15t 4), , x � a(t � b sin t), , y � c(at 2 � 3t 4), , 51. The parametric equations x � cos2 t and y � sin2 t, where, �⬁ � t � ⬁ , have the same graph as x � y � 1., , occurs in the study of catastrophe theory. Plot the curve with, a � �2 and c � 0.5 for t in the parameter interval, [�1.25, 1.25]., , 52. The graph of a function y � f(x) can always be represented, by a pair of parametric equations., 53. The curve with parametric equations x � f(t) � a and, y � t(t) � b is obtained from the curve C with parametric, equations x � f(t) and y � t(t) by shifting the latter horizontally and vertically., , 49. The Lissajous curves, also known as Bowditch curves,, have applications in physics, astronomy, and other sciences., They are described by the parametric equations, x � sin(at � bp),, , y � sin t, , a a rational number, and, , 54. The ellipse with center at the origin and major and minor, axes a and b, respectively, can be obtained from the circle, with equations x � f(t) � cos t and y � t(t) � sin t by multiplying f(t) and t(t) by appropriate nonzero constants., , Plot the curve with a � 0.75 and b � 0 for t in the parameter interval [0, 8p]., 50. The prolate cycloid is the path traced out by a fixed point at, a distance b � a from the center of a rolling circle, where a, , 10.3, , y � c(1 � d cos t), , In Exercises 51–54, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why it is true. If it is false, give an, example to show why it is false., , 48. The swallowtail catastrophe curve, which is described by, the parametric equations, and, , and, , Plot the curve with a � 0.1, b � 2, c � 0.25, and d � 2 for, t in the parameter interval [�10, 10]., , occurs in the study of catastrophe theory. Plot the curve with, a � �7 and c � 0.03 for t in the parameter interval, [�1.629, 1.629]., , x � c(�2at � 4t 3), , 857, , The Calculus of Parametric Equations, Tangent Lines to Curves Defined by Parametric Equations, Suppose that C is a smooth curve that is parametrized by the equations x � f(t) and, y � t(t) with parameter interval I and we wish to find the slope of the tangent line, to the curve at the point P. (See Figure 1.) Let t 0 be the point in I that corresponds to, P, and let (a, b) be the subinterval of I containing t 0 corresponding to the highlighted, portion of the curve C in Figure 1. This subset of C is the graph of a function of x, as, you can verify using the Vertical Line Test. (The general conditions that f and t must, satisfy for this to be true are given in Exercise 66.), y, , C, ( f(b), g(b)), , ( f(a), g(a)), , FIGURE 1, We want to find the slope of the tangent, line to the curve at the point P., , a, Parameter interval, , to, , b, , t, , f(a), , P( f(to), g(to)), , f(b), , x

Page 11 :

858, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, , Let’s denote this function by F so that y � F(x), where f(a) � x � f(b). Since, x � f(t) and y � t(t), we may rewrite this equation in the form, t(t) � F[ f(t)], Using the Chain Rule, we obtain, t¿(t) � F¿[f(t)] f ¿(t), � F¿(x)f ¿(t), If f ¿(t), , Replace f(t) by x., , 0, we can solve for F¿(x), obtaining, F¿(x) �, , t¿(t), f ¿(t), , which can also be written, dy, dy, dt, �, dx, dx, dt, , if, , dx, dt, , 0, , (1), , The required slope of the tangent line at P is then found by evaluating Equation (1) at, t 0. Observe that Equation (1) enables us to solve the problem without eliminating t., y, 2, 1, 0, , EXAMPLE 1 Find an equation of the tangent line to the curve, , (t � π4 ), , x � sec t, , FIGURE 2, The tangent line to the curve, at ( 12, 1), , �p2 � t � p2, , at the point where t � p>4. (See Figure 2.), , (√2, 1), 2, , y � tan t, , x, , Solution, , The slope of the tangent line at any point (x, y) on the curve is, dy, dy, dt, �, dx, dx, dt, �, , sec 2 t, sec t, �, sec t tan t, tan t, , In particular, the slope of the tangent line at the point where t � p>4 is, p, dy, 4, 12, `, �, �, � 12, dx t�p>4, p, 1, tan, 4, sec, , Also, when t � p>4, we have x � sec(p>4) � 12 and y � tan(p>4) � 1 giving, ( 12, 1) as the point of tangency. Finally, using the point-slope form of the equation, of a line, we obtain the required equation:, y � 1 � 12(x � 12), , or, , y � 12x � 1

Page 12 :

10.3 The Calculus of Parametric Equations, , 859, , Horizontal and Vertical Tangents, A curve C represented by the parametric equations x � f(t) and y � t(t) has a horizontal tangent at a point (x, y) on C where dy>dt � 0 and dx>dt 0 and a vertical, tangent where dx>dt � 0 and dy>dt 0, so that dy>dx is undefined there. Points where, both dy>dt and dx>dt are equal to zero are candidates for horizontal or vertical tangents, and may be investigated by using l’Hôpital’s rule., , EXAMPLE 2 A curve C is defined by the parametric equations x � t 2 and, y � t 3 � 3t., a. Find the points on C where the tangent lines are horizontal or vertical., b. Find the x- and y-intercepts of C., c. Sketch the graph of C., y, 2, C, 0, , 1, , 2, , 3, , x, , �2, , FIGURE 3, The graph of x � t 2, y � t 3 � 3t,, and the tangent lines at t � �1, , Solution, a. Setting dy>dt � 0 gives 3t 2 � 3 � 0, or t � �1. Since dx>dt � 2t 0 at these, values of t, we conclude that C has horizontal tangents at the points on C corresponding to t � �1, that is, at (1, �2) and (1, 2). Next, setting dx>dt � 0 gives, 2t � 0, or t � 0. Since dy>dt 0 for this value of t, we conclude that C has a, vertical tangent at the point corresponding to t � 0, or at (0, 0)., b. To find the x-intercepts, we set y � 0, which gives t 3 � 3t � t(t 2 � 3) � 0, or, t � � 13, 0, and 13. Substituting these values of t into the expression for x, gives 0 and 3 as the x-intercepts. Next, setting x � 0 gives t � 0, which, when, substituted into the expression for y, gives 0 as the y-intercept., c. Using the information obtained in parts (a) and (b), we obtain the graph of C, shown in Figure 3., , Finding d 2y>dx 2 from Parametric Equations, Suppose that the parametric equations x � f(t) and y � t(t) define y as a twicedifferentiable function of x over some suitable interval. Then d 2y>dx 2 may be found, from Equation (1) with another application of the Chain Rule., d dy, a b, d y, d dy, dt dx, �, a b�, dx dx, dx, dx 2, dt, 2, , if, , Higher-order derivatives are found in a similar manner., , EXAMPLE 3 Find, Solution, , d 2y, dx 2, , if x � t 2 � 4 and y � t 3 � 3t., , First, we use Equation (1) to compute, dy, dy, 3t 2 � 3, dt, �, �, dx, dx, 2t, dt, , dx, dt, , 0, , (2)

Page 13 :

860, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, , Then, using Equation (2), we obtain, d dy, d 3t 2 � 3, a b, a, b, d y, dt dx, dt, 2t, �, �, dx, 2t, dx 2, dt, 2, , (2t)(6t) � (3t 2 � 3)(2), 4t 2, 2t, , �, �, , 6t 2 � 6, 8t 3, , �, , Use the Quotient Rule., , 3(t 2 � 1), 4t 3, , The Length of a Smooth Curve, In Section 5.4 we showed that the length L of the graph of a smooth function f on an, interval [a, b] can be found by using the formula, b, , L�, , 冮 21 � [f ¿(x)] dx, 2, , (3), , a, , We now generalize this result to include curves defined by parametric equations., We begin by explaining what is meant by a smooth curve defined parametrically. Suppose that C is represented by x � f(t) and y � t(t) on a parameter interval I. Then C, is smooth if f ¿ and t¿ are continuous on I and are not simultaneously zero, except possibly at the endpoints of I. A smooth curve is devoid of corners or cusps. For example, the cycloid that we discussed in Section 10.2 (see Figure 9 in that section) has, sharp corners at the values x � 2npa and, therefore, is not smooth. However, it is, smooth between these points., Now let P � {t 0, t 1, p , t n} be a regular partition of the parameter interval [a, b]., Then the point Pk( f(t k), t(t k)) lies on C, and the length of C is approximated by the, length of the polygonal curve with vertices P0, P1, p , Pn. (See Figure 4.) Thus,, n, , L ⬇ a d(Pk�1, Pk), , (4), , k�1, , where, d(Pk�1, Pk) � 2[ f(t k) � f(t k�1)]2 � [t(t k) � t(t k�1)]2, y, , Pn ( f(tn), g(tn)), , P2 ( f(t2), g(t2)), , Pn�1 ( f(tn�1), g(tn�1)), C, Pk ( f(tk), g(tk)), , P1 ( f(t1), g(t1)), , Pk�1 ( f(tk�1), g(tk�1)), P0 ( f(t0), g(t0)), a � t0 t1, , t2, , tk�1 tk, , b � tn t, , 0, , Parameter interval, , FIGURE 4, The length of C is approximated by the length of the polygonal curve (the red lines)., , x

Page 14 :

10.3 The Calculus of Parametric Equations, , 861, , Now, since f and t both have continuous derivatives, we can use the Mean Value Theorem to write, f(t k) � f(t k�1) � f ¿(t *k )(t k � t k�1), and, t(t k) � t(t k�1) � t¿(t **, k )(t k � t k�1), where t *k and t **, k are numbers in (t k�1, t k) . Substituting these expressions into Equation (4) gives, n, , n, , 2, L ⬇ a d(Pk�1, Pk) � a 2[ f ¿(t *k )]2 � [t¿(t **, k )] ⌬t, k�1, , (5), , k�1, , As in Section 5.4, we define, n, , L � lim a d(Pk�1, Pk), n→⬁, k�1, n, 2, � lim a 2[ f ¿(t *k )]2 � [t¿(t **, k )] ⌬t, n→⬁, , (6), , k�1, , The sum in Equation (6) looks like a Riemann sum of the function 2[ f ¿]2 � [t¿]2, but, it is not, because t *k is not necessarily equal to t **, k . But it can be shown that the limit, in Equation (6) is the same as that of an expression in which t *k � t **, k . Therefore,, b, , L�, , 冮 2[ f ¿(t)], , � [t¿(t)]2 dt, , 2, , a, , and we have the following result., , THEOREM 1 Length of a Smooth Curve, Let C be a smooth curve represented by the parametric equations x � f(t) and, y � t(t) with parameter interval [a, b]. If C does not intersect itself, except possibly for t � a and t � b, then the length of C is, L�, , 冮, , b, , 2[ f ¿(t)]2�[t¿(t)]2 dt �, , a, , 冮, , a, , b, , dy 2, dx 2, b � a b dt, B dt, dt, a, , (7), , Note Equation (7) is consistent with Equation (4) of Section 5.4. Both have the form, L � 兰 ds, where (ds)2 � (dx)2 � (dy)2., , EXAMPLE 4 Find the length of one arch of the cycloid, x � a(u � sin u), , y � a(1 � cos u), , (See Example 6 in Section 10.2.), Solution, , One arch of the cycloid is traced out by letting u run from 0 to 2p. Now, dx, � a(1 � cos u), du, , and, , dy, � a sin u, du

Page 15 :

862, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, , Therefore, using Equation (7), we find the required length to be, L�, , 冮, , 2p, , 冮, , 2p, , dy 2, dx 2, b � a b du �, B du, du, , 0, , �, , 冮, , a, , 2p, , 2a 2 (1 � cos u)2 � a 2 sin2 u du, , 0, , 2a 2 � 2a 2 cos u � a 2 cos2 u � a 2 sin2 u du, , 0, , �a, , 冮, , 2p, , 12(1 � cos u) du, , sin2 u � cos2 u � 1, , 0, , To evaluate this integral, we use the identity sin2 x � 12 (1 � cos 2x) with u � 2x. This, gives 1 � cos u � 2 sin2(u>2), so, L�a, , 冮, , 2p, , B, , 0, , � 2a, , 冮, , 4 sin2, , 0, , 2p, , sin, , u, du, 2, , u, du, 2, , sin, , u, � 0 on [0, 2p], 2, , u 2p, � �4accos d, 2 0, � �4a(�1 � 1) � 8a, , The Area of a Surface of Revolution, Recall that the formulas S � 2p 兰 y ds and S � 2p 兰 x ds (Formulas 11 and 12 of Section 5.4) give the area of the surface of revolution that is obtained by revolving the graph, of a function about the x- and y-axes, respectively. These formulas are valid for finding, the area of the surface of revolution that is obtained by revolving a curve described by, parametric equations about the x- and the y-axes, provided that we replace the element, of arc length ds by the appropriate expression. These results, which may be derived by, using the method used to derive Equation (7), are stated in the next theorem., , THEOREM 2 Area of a Surface of Revolution, Let C be a smooth curve represented by the parametric equations x � f(t) and, y � t(t) with parameter interval [a, b], and suppose that C does not intersect, itself, except possibly for t � a and t � b. If t(t) � 0 for all t in [a, b], then the, area S of the surface obtained by revolving C about the x-axis is, S � 2p, , 冮, , b, , y2[ f ¿(t)]2 � [t¿(t)]2 dt � 2p, , a, , b, , 冮, , dy 2, dx 2, y a b � a b dt, B dt, dt, , a, , (8), , If f(t) � 0 for all t in [a, b], then the area S of the surface that is obtained by, revolving C about the y-axis is, b, , S � 2p, , 冮 x2[ f ¿(t)], , 2, , b, , � [t¿(t)]2 dt � 2p, , a, , 冮 xB a dt b, dx, , 2, , a, , �a, , dy 2, b dt, dt, , EXAMPLE 5 Show that the surface area of a sphere of radius r is 4pr 2., Solution, , We obtain this sphere by revolving the semicircle, x � r cos t, , y � r sin t, , 0, , t, , p, , (9)

Page 16 :

10.3 The Calculus of Parametric Equations, , 863, , about the x-axis. Using Equation (8), the surface area of the sphere is, S � 2p, , 冮, , p, , r sin t2(�r sin t)2 � (r cos t)2 dt, , 0, , � 2pr, , 冮, , p, , 冮, , p, , sin t2r 2 (sin2 t � cos2 t) dt, , 0, , � 2pr, , sin2 t � cos2 t � 1, , r sin t dt, , 0, , � 2pr 2 C�cos tD 0 � 2pr 2[�(�1) � 1] � 4pr 2, p, , 10.3, , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, , 1. Suppose that C is a smooth curve with parametric equations, x � f(t) and y � t(t) and parameter interval I. Write an, expression for the slope of the tangent line to C at the point, (x 0, y0) corresponding to t 0 in I., 2. Suppose that C is a smooth curve with parametric equations, x � f(t) and y � t(t) and parameter interval [a, b]. Furthermore, suppose that C does not cross itself, except possibly, for t � a. Write an expression giving the length of C., 3. Suppose that C is a smooth curve with parametric equations, x � f(t) and y � t(t) and parameter interval [a, b]. Suppose,, , 10.3, , further, that C does not intersect itself, except possibly for, t � a and t � b., a. Write an integral giving the area of the surface obtained, by revolving C about the x-axis assuming that t(t) � 0, for all t in [a, b]., b. Write an integral giving the area of the surface obtained, by revolving C about the y-axis assuming that f(t) � 0, for all t in [a, b]., , EXERCISES, , In Exercises 1–6, find the slope of the tangent line to the curve, at the point corresponding to the value of the parameter., 1. x � t 2 � 1,, , y � t 2 � t;, , 2. x � t � t,, , y � t � 2t � 2; t � 2, , 3, , 9. x � t 2 � t,, , 2, , 3. x � 1t,, , 1, y� ; t�1, t, , 4. x � e2t,, , y � ln t;, , 5. x � 2 sin u,, , t�1, , 10. x � e ,, t, , u�, , p, 4, , �t, , y�e ;, , (0, 2), , (1, 1), , y � 2(1 � cos u);, , y � t 3 � t 2;, , t�1, , y � u sin u;, , p, u�, 2, , 11. x � 2t 2 � 1,, , y � t 3;, , 12. x � t ,, , 2, , 3, , u�, , p, 6, , In Exercises 7 and 8, find an equation of the tangent line to the, curve at the point corresponding to the value of the parameter., , 8. x � u cos u,, , y � t 2 � t 3;, , In Exercises 11 and 12, find the points on the curve at which the, slope of the tangent line is m., , t�1, , y � 3 cos u;, , 6. x � 2(u � sin u),, , 7. x � 2t � 1,, , In Exercises 9 and 10, find an equation of the tangent line to the, curve at the given point. Then sketch the curve and the tangent, line(s)., , y � t � t;, , m�3, m�1, , In Exercises 13–16, find the points on the curve at which the, tangent line is either horizontal or vertical. Sketch the curve., 13. x � t 2 � 4,, , y � t 3 � 3t, , 14. x � t 3 � 3t,, , y � t2, , 15. x � 1 � 3 cos t,, 16. x � sin t,, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login., , y � 2 � 2 sin t, , y � sin 2t

Page 17 :

864, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, 33. x � sin2 t,, , In Exercises 17–24, find dy>dx and d 2y>dx 2., 17. x � 3t � 1,, , y � 2t, , 2, , 19. x � 1t,, , 18. x � t � t, y � t � 2t, , 3, , 3, , 1, y�, t, , 3, , 20. x � sin 2t,, , 2, , y � cos 2t, , 34. x � e cos t,, t, , y � cos 2t; 0, y � e sin t;, t, , t, 0, , p, t, , p, , 35. x � a(cos t � t sin t), y � a(sin t � t cos t);, , 0, , p, 2, , t, , y � (2 � t 2)cos t � 2t sin t;, , 21. x � u � cos u, y � u � sin u, , 36. x � (t 2 � 2)sin t � 2t cos t,, 0 t p, , 22. x � e�t, y � e2t, , 37. Find the length of the cardioid with parametric equations, , 23. x � cosh t, y � sinh t, , x � a(2 cos t � cos 2t), , 24. x � 2t 2 � 1, y � t ln t, , and y � a(2 sin t � sin 2t), , 38. Find the length of the astroid with parametric equations, , 25. Let C be the curve defined by the parametric equations, x � t 2 and y � t 3 � 3t (see Example 2). Find d 2y>dx 2, and, use this result to determine the intervals where C is concave, upward and where it is concave downward., , x � a cos3 t, , y � a sin3 t, , and, , (See the figure for Exercise 27. Compare with Exercise 25, in Section 5.4.), , 26. Show that the curve defined by the parametric equations, x � t 2 and y � t 3 � 3t crosses itself. Find equations of the, tangent lines to the curve at that point (see Example 2)., , 39. The position of an object at any time t is (x, y), where, x � cos2 t and y � sin2 t, 0 t 2p. Find the distance, covered by the object as t runs from t � 0 to t � 2p., , 27. The parametric equations of the astroid x 2>3 � y 2>3 � a 2>3, are x � a cos3 t and y � a sin3 t. (Verify this!) Find an, expression for the slope of the tangent line to the astroid in, terms of t. At what points on the astroid is the slope of the, tangent line equal to �1? Equal to 1?, , 40. The following figure shows the course taken by a yacht during a practice run. The parametric equations of the course are, , y, , x � 412 sin t, , y � sin 2t, , 0, , t, , 2p, , where x and y are measured in miles. Find the length of the, course., y (mi), , a, , 1, , �a, , x, , a, , �4 �2, , 28. Find dy>dx and d 2y>dx 2 if, , 冮, , 1, , t, , sin u, du, u, , y�, , and, , 冮, , ln t, , eu du, , 2, , 29. The function y � f(x) is defined by the parametric equations, x � t 5 � 5t 3 � 10t � 2, , 4, , x (mi), , �1, , �a, , x�, , 2, , and y � 2t 3 � 3t 2 � 12t � 1, �2 t 2, , Find the absolute maximum and the absolute minimum, values of f., 30. Find the points on the curve with parametric equations, x � t 3 � t and y � t 2 at which the tangent line is parallel to, the line with parametric equations x � 2t and y � 2t � 4., , 41. Path of a Boat Two towns, A and B, are located directly opposite each other on the banks of a river that is 1600 ft wide, and flows east with a constant speed of 4 ft/sec. A boat leaving Town A travels with a constant speed of 18 ft/sec always, aimed toward Town B. It can be shown that the path of the, boat is given by the parametric equations, x � 800(t 7>9 � t 11>9), , y � 1600t, , 0, , t, , 1, , Find the distance covered by the boat in traveling from, A to B., y, B, , In Exercises 31–36, find the length of the curve defined by the, parametric equations., 31. x � 2t 2, y � 3t 3; 0, , t, , 1, , 32. x � 2t 3>2,, , 0, , t, , y � 3t � 1;, , 4, , A, 0, , x

Page 18 :

10.3 The Calculus of Parametric Equations, 42. Trajectory of an Electron An electron initially located at the, origin of a coordinate system is projected horizontally into, a uniform electric field with magnitude E and directed, upward. If the initial speed of the electron is √0, then its, trajectory is, , 865, , 47. Use the result of Exercise 46 to find the area of the region, under one arch of the cycloid x � a(u � sin u),, y � a(1 � cos u)., y, , 1 eE, y � � a bt 2, 2 m, , x � √0t, , where e is the charge of the electron and m is its mass., Show that the trajectory of the electron is a parabola., 0, , y, Screen, , 0, , x, , 2πa, , 48. Use the result of Exercise 46 to find the area of the region, enclosed by the ellipse with parametric equations, x � a cos u, y � b sin u, where 0 u 2p., 49. Use the result of Exercise 46 to find the area of the region, enclosed by the astroid x � a cos3 u, y � a sin3 u. (See the, figure for Exercise 27.), , x, , 50. Use the result of Exercise 46 to find the area of the region, enclosed by the curve x � a sin t, y � b sin 2t., Note: The deflection of electrons by an electric field is used to con-, , 51. Use the result of Exercise 46 to find the area of the region, lying inside the course taken by the yacht of Exercise 40., , trol the direction of an electron beam in an electron gun., , 43. Refer to Exercise 42. If a screen is placed along the vertical, line x � a, at what point will the electron beam hit the, screen?, 44. Find the point that is located one quarter of the way along, the arch of the cycloid, x � a(t � sin t), , y � a(1 � cos t), , 0, , t, , 2p, , as measured from the origin. What is the slope of the tangent line to the cycloid at that point? Plot the arch of the, cycloid and the tangent line on the same set of axes., 45. The cornu spiral is a curve defined by the parametric equations, x � C(t) �, , 冮, , t, , 0, , t, , cos(pu 2>2) du, , y � S(t) �, , 冮 sin(pu >2) du, 2, , 0, , where C and S are the Fresnel functions discussed in Section 6.7., a. Plot the spiral. Describe the behavior of the curve as, t → ⬁ and as t → �⬁ ., b. Find the length of the spiral from t � 0 to t � a., 46. Suppose that the graph of a nonnegative function F on an, interval [a, b] is represented by the parametric equations, x � f(t) and y � t(t) for t in [a, b]. Show that the area of, the region under the graph of F is given by, b, , 冮 t(t)f ¿(t) dt, a, , a, , or, , 冮 t(t)f ¿(t) dt, , In Exercises 52–57, find the area of the surface obtained by, revolving the curve about the x-axis., 52. x � t,, , y � 2 � t;, , 53. x � t 3,, , y � t 2;, , 54. x � 13t 2,, 55. x �, , 0, , t, , 0, , 1, , y � t � t 3;, , 1 3, t ,, 3, , y�4�, , 56. x � et sin t,, , 2, , t, , 0, , 1 2, t ;, 2, , 0, , y � et cos t;, , 57. x � t � sin t,, , t, , 1, t, , 212, , 0, , t, , p, 2, , y � 1 � cos t;, , 0, , t, , 2p, , In Exercises 58–61, find the area of the surface obtained by, rotating the curve about the y-axis., 58. x � t,, , y � 2t;, , 59. x � 3t ,, 2, , 0, , t, , y � 2t ;, , 0, , 3, , 4, t, , 60. x � a cos t,, , y � b sin t;, , 61. x � et � t,, , y � 4et>2;, , 0, , 1, �p2, , t, , t, , 1, , p, 2, , 62. Find the area of the surface obtained by revolving the cardioid, x � a(2 cos t � cos 2t), , y � a(2 sin t � sin 2t), , about the x-axis., 63. Find the area of the surface obtained by revolving the astroid, x � a cos3 t, , y � a sin3 t, , about the x-axis., , b, , 64. Find the areas of the surface obtained by revolving one arch, of the cycloid x � a(u � sin u), y � a(1 � cos u) about the, x- and y-axes.

Page 19 :

866, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, , 65. Find the surface area of the torus obtained by revolving the, circle x 2 � (y � b)2 � r 2 (0 � r � b) about the x-axis., Hint: Represent the equation of the circle in parametric form:, x � r cos t, y � b � r sin t, 0, , 2p., , t, , 66. Show that if f ¿ is continuous and f ¿(t) 0 for a t b,, then the parametric curve defined by x � f(t) and y � t(t), for a t b can be put in the form y � F(x)., cas In Exercises 67–70, (a) plot the curve defined by the parametric, , 74. Use the parametric representation of a circle in Exercise 73, to show that the circumference of a circle of radius a is, 2pa., 75. Find parametric equations for the Folium of Descartes,, x 3 � y 3 � 3axy with parameter t � y>x., cas 76. Use the parametric representation of the Folium of Descartes, , to estimate the length of the loop., cas 77. Show that the length of the ellipse x � a cos t, y � b sin t,, , 0, , equations and (b) estimate the arc length of the curve accurate, to four decimal places., 67. x � 2t ,, 2, , y�t�t ;, 3, , 0, , 68. x � sin(0.5t � 0.4p),, , 0�t, , 4p, , e�, 3 2, t b;, 2, , �2 � t � 2, , y � 2 cos 3t, , 0, , t, , is the eccentricity of the ellipse., cas 78. Use a computer or calculator and the result of Exercise 77, , to estimate the circumference of the ellipse, y2, x2, �, �1, 100, 36, , p, 6, , about the x-axis., 72. a. Find an expression for the arc length of the curve defined, by the parametric equations, y � �f ⬙(t)sin t � f ¿(t)cos t, , where a t b and f has continuous third-order derivatives., b. Use the result of part (a) to find the arc length, of the curve x � 6t cos t � 3t 2 sin t and, y � �6t sin t � 3t 2 cos t, where 0 t 1., 73. Show that, 1 � t2, , y�, , c, 2a 2 � b 2, �, a, a, , Note: The integral is called an elliptical integral of the second kind., , surface obtained by revolving the curve, , x�, , 21 � e2 sin2 t dt, , where, , (swallowtail castastrophe), , 2at, , p>2, , 0, , cas 71. Use a calculator or computer to approximate the area of the, , x � f ⬙(t)cos t � f ¿(t)sin t, , 冮, , y � 0.2(6 sin t � sin 6t);, , y � �t 2 a1 �, , x � 4 sin 2t, , 2p, where a � b � 0, is given by, L � 4a, , 1, , y � sin t;, , 69. x � 0.2(6 cos t � cos 6t),, 0 t p, 70. x � 2t(1 � t 2),, , t, , t, , a(1 � t 2), , accurate to three decimal places., In Exercises 79–80, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why it is true. If it is false, give an, example to show why it is false., 79. If x � f(t) and y � t(t), f and t have second-order derivatives, and f ¿(t) 0, then, d 2y, dx, , 2, , �, , f ¿(t)t⬙(t) � t¿(t)f ⬙(t), [ f ¿(t)]2, , 80. The curve with parametric equations x � f(t) and y � t(t) is, a line if and only if f and t are both linear functions of t., , 1 � t2, , where a � 0 and �⬁ � t � ⬁ , are parametric equations of, a circle. What are its center and radius?, , 10.4, , Polar Coordinates, The curve shown in Figure 1a is a lemniscate, and the one shown in Figure 1b is called, a cardioid. The rectangular equations of these curves are, (x 2 � y 2)2 � 4(x 2 � y 2), , and, , x 4 � 2x 3 � 2x 2y 2 � 2xy 2 � y 2 � y 4 � 0, , respectively. As you can see, these equations are somewhat complicated. For example,, they will not prove very helpful if we want to calculate the area enclosed by the two, loops of the lemniscate shown in Figure 1a or the length of the cardioid shown in Figure 1b.

Page 20 :

10.4 Polar Coordinates, , 867, , y, , y, , 1, , 2 x, , �2, , 2 x, �1, , (a) A lemniscate, , (b) A cardioid, , FIGURE 1, A rectangular equation of the lemniscate in part (a) is (x 2 � y 2)2 � 4(x 2 � y 2), and an equation, of the cardioid in part (b) is x 4 � 2x 3 � 2x 2y 2 � 2xy 2 � y 2 � y 4 � 0., , A question that arises naturally is: Is there a coordinate system other than the rectangular system that we can use to give a simpler representation for curves such as the, lemniscate and cardioid? One such system is the polar coordinate system., , The Polar Coordinate System, P (r, ¨), r, ¨, O Pole, , Polar axis, , FIGURE 2, , To construct the polar coordinate system, we fix a point O called the pole (or origin), and draw a ray (half-line) emanating from O called the polar axis. Suppose that P is, any point in the plane, let r denote the distance from O to P, and let u denote the angle, (in degrees or radians) between the polar axis and the line segment OP. (See Figure 2.), Then the point P is represented by the ordered pair (r, u), also written P(r, u), where, the numbers r and u are called the polar coordinates of P., The angular coordinate u is positive if it is measured in the counterclockwise, direction from the polar axis and negative if it is measured in the clockwise direction., The radial coordinate r may assume positive as well as negative values. If r � 0, then, P(r, u) is on the terminal side of u and at a distance r from the origin. If r � 0, then, P(r, u) lies on the ray that is opposite the terminal side of u and at a distance of 冟 r 冟 � �r, from the pole. (See Figure 3.) Also, by convention the pole O is represented by the, ordered pair (0, u) for any value of u. Finally, a plane that is endowed with a polar, coordinate system is referred to as an ru-plane., (�r, ¨), , P (r, ¨), r, , r, ¨, , ¨, , O, , O, |r|, P (r, ¨), , FIGURE 3, , (a) r > 0, , (b) r < 0, , EXAMPLE 1 Plot the following points in the ru-plane., , a. 1 1, 2p, 3 2, , b. 1 2, �p4 2, , c. 1 �2, p3 2, , d. (2, �3p)

Page 21 :

868, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, , Solution, , The points are plotted in Figure 4., , (1, 2π3 ), , π, 3, , 2π, 3, 0, , 1, , 0, , 0, , 1, �π, 4, , (2, �3π), , (2, � π4 ), (a), , �3π, , 1, , 1, , (�2, π3 ), , (b), , (c), , (d), , FIGURE 4, The points in Example 1, , Unlike the representation of points in the rectangular system, the representation of, points using polar coordinates is not unique. For example, the point (r, u) can also be, written as (r, u � 2np) or (�r, u � (2n � 1)p), where n is any integer. Figures 5a, and 5b illustrate this for the case n � 1 and n � 0, respectively., (r, ¨) � (�r, ¨ � π), , (r, ¨) � (r, ¨ � 2π), ¨�π, , r, , ¨, , ¨, ¨ � 2π, , FIGURE 5, Representation of points using, polar coordinates is not unique., , (a) n � 1, , (b) n � 0, , Relationship Between Polar and Rectangular Coordinates, To establish the relationship between polar and rectangular coordinates, let’s superimpose an xy-plane on an ru-plane in such a way that the origins coincide and the positive x-axis coincides with the polar axis. Let P be any point in the plane other than the, origin with rectangular representation (x, y) and polar representation (r, u). Figure 6a, shows a situation in which r � 0, and Figure 6b shows a situation in which r � 0. If, r � 0, we see immediately from the figure that, cos u �, y, , x, r, , sin u �, , y, r, y, , P (r, ¨), P (x, y), , P (�x, �y), |r|, , r, , ¨, , ¨, 0, , FIGURE 6, The relationship between polar, and rectangular coordinates, , x, , 0, P (r, ¨), P (x, y), , (a) r > 0, , (b) r < 0, , x

Page 22 :

10.4 Polar Coordinates, , 869, , so x � r cos u and y � r sin u. If r � 0, we see by referring to Figure 6b that, cos u �, , �x, �x, x, �, �, 冟r冟, �r, r, , sin u �, , �y, �y, y, �, �, 冟r冟, �r, r, , so again x � r cos u and y � r sin u. Finally, in either case we have, x 2 � y2 � r 2, , tan u �, , and, , y, x, , if x, , 0, , Relationship Between Rectangular and Polar Coordinates, Suppose that a point P (other than the origin) has representation (r, u) in polar, coordinates and (x, y) in rectangular coordinates. Then, x � r cos u, r 2 � x 2 � y2, , and, , y � r sin u, tan u �, , and, , y, x, , if x, , (1), 0, , (2), , EXAMPLE 2 The point 1 4, p6 2 is given in polar coordinates. Find its representation, , in rectangular coordinates., Solution, , Here, r � 4 and u � p>6. Using Equation (1), we obtain, x � r cos u � 4 cos, y � r sin u � 4 sin, , p, 13, �4ⴢ, � 213, 6, 2, , p, 1, �4ⴢ �2, 6, 2, , Therefore, the given point has rectangular representation (2 13, 2)., , EXAMPLE 3 The point (�1, 1) is given in rectangular coordinates. Find its representation in polar coordinates., Solution, , Here, x � �1 and y � 1. Using Equation (2), we have, r 2 � x 2 � y 2 � (�1)2 � 12 � 2, , and, tan u �, , y, � �1, x, , Let’s choose r to be positive; that is, r � 12. Next, observe that the point (�1, 1), lies in the second quadrant and so we choose u � 3p>4 (other choices are, u � (3p>4) � 2np, where n is an integer). Therefore, one representation of the given, point is 1 12, 3p, 4 2., , Graphs of Polar Equations, The graph of a polar equation r � f(u) or, more generally, F(r, u) � 0 is the set of, all points (r, u) whose coordinates satisfy the equation.

Page 23 :

870, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, , EXAMPLE 4 Sketch the graphs of the polar equations, and reconcile your results by, finding the corresponding rectangular equations., a. r � 2, , b. u �, , 2p, 3, , Solution, a. The graph of r � 2 consists of all points P(r, u) where r � 2 and u can assume, any value. Since r gives the distance between P and the pole O, we see that the, graph consists of all points that are located a distance of 2 units from the pole;, in other words, the graph of r � 2 is the circle of radius 2 centered at the pole., (See Figure 7a.) To find the corresponding rectangular equation, square both sides, of the given equation obtaining r 2 � 4. But by Equation (2), r 2 � x 2 � y 2, and, this gives the desired equation x 2 � y 2 � 4. Since this is a rectangular equation, of a circle with center at the origin and radius 2, the result obtained earlier has, been confirmed., y, , y, P (r, ¨), 2π, ¨� 3, , r�2, 2, x, , O, , FIGURE 7, , 2π, 3, O, , x, , 2π, (b) The graph of ¨ � 3, , (a) The graph of r � 2, , b. The graph of u � 2p>3 consists of all points P(r, u) where u � 2p>3 and r can, assume any value. Since u measures the angle the line segment OP makes with, the polar axis, we see that the graph consists of all points that are located on the, straight line passing through the pole O and making an angle of 2p>3 radians, with the polar axis. (See Figure 7b.) Observe that the half-line in the second, quadrant consists of points for which r � 0, whereas the half-line in the fourth, quadrant consists of points for which r � 0. To find the corresponding rectangular equation, we use Equation (2), tan u � y>x, to obtain, tan, , y, 2p, �, x, 3, , or, , y, � � 13, x, , or y � � 13x. This equation confirms that the graph of u � 2p>3 is a straight, line with slope � 13., As in the case with rectangular equations, we can often obtain a sketch of the graph, of a simple polar equation by plotting and connecting some points that lie on the graph., , EXAMPLE 5 Sketch the graph of the polar equation r � 2 sin u. Find a corresponding rectangular equation and reconcile your results., Solution The following table shows the values of r corresponding to some convenient, values of u. It suffices to restrict the values of u to those lying between 0 and p, since, values of u beyond p will give the same points (r, u) again.

Page 24 :

10.4 Polar Coordinates, , 0, , p, 6, , p, 4, , p, 3, , p, 2, , 2p, 3, , 3p, 4, , 5p, 6, , p, , r, , 0, , 1, , 12 ⬇ 1.4, , 13 ⬇ 1.7, , 2, , 13 ⬇ 1.7, , 12 ⬇ 1.4, , 1, , 0, , The graph of r � 2 sin u is sketched in Figure 8. To find a corresponding rectangular equation, we multiply both sides of r � 2 sin u by r to obtain r 2 � 2r sin u and, then use the relationships r 2 � x 2 � y 2 (Equation (2)) and y � r sin u (Equation (1)),, to obtain the desired equation, , (2, π2 ), (√ 3, π3 ), (√ 2, π4 ), (1, π6 ), , (√ 3, 2π3 ), (√ 2, 3π4 ), (1, 5π6 ), , U, , 871, , x 2 � y 2 � 2y, , x 2 � y 2 � 2y � 0, , or, , Finally, completing the square in y, we have, , O, , FIGURE 8, The graph of r � 2 sin u is a circle. To, plot the points, first draw the ray with, the desired angle, then locate the point, by measuring off the required distance, from the pole., , x 2 � y 2 � 2y � (�1)2 � 1, or, x 2 � (y � 1)2 � 1, which is an equation of the circle with center (0, 1) and radius 1, as obtained earlier., , It might have occurred to you that in the last several examples we could have, obtained the graphs of the polar equations by first converting them to the corresponding rectangular equations. But as you will see, some curves are easier to graph using, polar coordinates., , Symmetry, Just as the use of symmetry is helpful in graphing rectangular equations, its use is, equally helpful in graphing polar equations. Three types of symmetry are illustrated in, Figure 9. The test for each type of symmetry follows., , (r, ¨), , O, , ¨=π, 2, (r, π � ¨), π�¨, , ¨, �¨, , (r, ¨), , ¨, O, , O, (�r, ¨), , (r, �¨), , FIGURE 9, Symmetries of graphs, of polar equations, , (r, ¨), ¨, , (a) Symmetry with respect to, the polar axis, , (b) Symmetry with respect to, the line ¨ = π, 2, , (c) Symmetry with respect to, the pole, , Tests for Symmetry, a. The graph of r � f(u) is symmetric with respect to the polar axis if the, equation is unchanged when u is replaced by �u., b. The graph of r � f(u) is symmetric with respect to the vertical line, u � p>2 if the equation is unchanged when u is replaced by p � u., c. The graph of r � f(u) is symmetric with respect to the pole if the equation is unchanged when r is replaced by �r or when u is replaced by, u � p.

Page 25 :

872, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, , To illustrate the use of the tests for symmetry, consider the equation r � 2 sin u of, Example 5. Here, f(u) � 2 sin u, and since, f(p � u) � 2 sin(p � u) � 2(sin p cos u � cos p sin u) � 2 sin u � f(u), we conclude that the graph of r � 2 sin u is symmetric with respect to the vertical line, u � p>2 (Figure 8)., , EXAMPLE 6 Sketch the graph of the polar equation r � 1 � cos u. This is the polar, form of the rectangular equation x 4 � 2x 3 � 2x 2y 2 � 2xy 2 � y 2 � y 4 � 0 of the cardioid that was mentioned at the beginning of this section (Figure 1b)., Solution, , Writing f(u) � 1 � cos u and observing that, f(�u) � 1 � cos(�u) � 1 � cos u � f(u), , we conclude that the graph of r � 1 � cos u is symmetric with respect to the polar, axis. In view of this, we need only to obtain that part of the graph between u � 0 and, u � p. We can then complete the graph using symmetry., To sketch the graph of r � 1 � cos u for 0 u p, we can proceed as we did in, Example 5 by first plotting some points lying on that part of the graph, or we may proceed as follows: Treat r and u as rectangular coordinates, and make use of our knowledge of graphing rectangular equations to obtain the graph of r � f(u) � 1 � cos u on, the interval [0, p]. (See Figure 10a.) Then recalling that u is the angular coordinate, and r is the radial coordinate, we see that as u increases from 0 to p, the points on, the respective rays shrink to 0. (See Figure 10b, where the corresponding points are, shown.), r, 2, , a, , (π4 , 1 � √22 ), b, , 1, , c, , π, 2, , ¨ �π, 4, 1, , b, 1, , (π2 , 1), d, , π, 4, , ¨ �π, 2, , ¨ � 3π, 4, , ( 3π4 , 1 � √22 ), 3π, 4, , e, π, , c, 2, a, , d, e O, , ¨, , (a) r � f(¨), treating r and ¨ as rectangular coordinates, , 2, , ¨�0, , (b) r � f(¨), treating r and ¨ as polar coordinates, , FIGURE 10, Two steps in sketching the graph of the polar equation r � 1 � cos u, , �1, , FIGURE 11, The graph of r � 1 � cos u, is a cardioid., , Finally, using symmetry, we complete the graph of r � 1 � cos u, as shown in Figure 11. It is called a cardioid because it is heart-shaped., , EXAMPLE 7 Sketch the graph of the polar equation r � 2 cos 2u., Solution, , Write f(u) � 2 cos 2u, and observe that, f(�u) � 2 cos 2(�u) � 2 cos 2u � f(u), , and, f(p � u) � 2 cos 2(p � u) � 2 cos(2p � 2u), � 2[cos 2p cos 2u � sin 2p sin 2u] � 2 cos 2u � f(u)

Page 26 :

10.4 Polar Coordinates, , 873, , Therefore, the graph of the given equation is symmetric with respect to both the polar, axis and the vertical line u � p>2. It suffices, therefore, to obtain an accurate sketch, of that part of the graph for 0 u p2 and then complete the sketch of the graph using, symmetry. Proceeding as in Example 6, we first sketch the graph of r � 2 cos 2u for, 0 u p2 treating r and u as rectangular coordinates (Figure 12a), and then transcribe, the information contained in this graph onto the graph in the ru-plane for 0 u p2 ., (See Figure 12b.), ¨ �π, 2, , r, 2, , a, , (π8 , √ 2 ), , b, 1, , 0.5, c, , c, π, 8, , π, 4, , d, , ¨, , π, 2, , 3π, 8, , �1, , ¨ �π, 4, ¨ �π, 8, , b, a, 2, , ( 3π8 , �√ 2 ), , �2, , FIGURE 12, Two steps in sketching the, graph of r � 2 cos 2u, , ¨ � 3π, 8, , d, , e, , e �2, , (a) r � f(¨) treating r and ¨ as, rectangular coordinates, , (b) r � f(¨), treating r and ¨ as, polar coordinates, , Finally, using the symmetry that was established earlier (Figure 13a), we complete, the graph of r � 2 cos 2u as shown in Figure 13b. This graph is called a four-leaved, rose., 2, , 2, �2, , FIGURE 13, The graph of r � 2 cos 2u, is a four-leaved rose., , �2, (a), , (b), , The next example shows how the graph of a rectangular equation can be sketched, more easily by first converting it to polar form., , EXAMPLE 8 Sketch the graph of the equation (x 2 � y 2)2 � 4(x 2 � y 2) by first converting it to polar form. This is an equation of the lemniscate that was mentioned at, the beginning of this section., Solution To convert the given equation to polar form, we use Equations (1) and (2),, obtaining, (r 2)2 � 4(r 2 cos2 u � r 2 sin2 u), � 4r 2(cos2 u � sin2 u), r 4 � 4r 2 cos 2u

Page 27 :

874, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, , or, r 2 � 4 cos 2u, Observe that f(u) � 21cos 2u is defined for �p4, u p4 and 3p, u 5p, 4, 4 . Also,, observe that f(�u) � f(u) and f(p � u) � f(u). (These computations are similar to, those in Example 7.) So the graph of r � 21cos 2u is symmetric with respect to the, polar axis and the line u � p>2. The graph of r � f(u) for 0 u p4 , where r and u, are treated as rectangular coordinates, is shown in Figure 14a. This leads to the part of, the required graph for 0 u p4 shown in Figure 14b. Then, using symmetry, we, obtain the graph of r � 21cos 2u and, therefore, that of (x 2 � y 2)2 � 4(x 2 � y 2), as, shown in Figure 15., r, ¨ �π, 4, , 2, , π, 4, , (a), , �2, , ¨, , 2, , 2, , FIGURE 15, The graph of r � 21cos 2u is a, lemniscate., , (b), , FIGURE 14, Two steps in sketching the graph of r � 21cos 2u, , Tangent Lines to Graphs of Polar Equations, To find the slope of the tangent line to the graph of r � f(u) at the point P(r, u), let, P(x, y) be the rectangular representation of P. Then, x � r cos u � f(u) cos u, y � r sin u � f(u) sin u, We can view these equations as parametric equations for the graph of r � f(u) with, parameter u. Then, using Equation (1) of Section 10.3, we have, dy, dr, sin u � r cos u, dy, du, du, �, �, dx, dx, dr, cos u � r sin u, du, du, , if, , dx, du, , 0, , (3), , and this gives the slope of the tangent line to the graph of r � f(u) at any point P(r, u)., The horizontal tangent lines to the graph of r � f(u) are located at the points where, dy>du � 0 and dx>du 0. The vertical tangent lines are located at the points where, dx>du � 0 and dy>du 0 (so that dy>dx is undefined). Also, points where both dy>du, and dx>du are equal to zero are candidates for horizontal or vertical tangent lines,, respectively, and may be investigated using l’Hôpital’s Rule., Equation (3) can be used to help us find the tangent lines to the graph of r � f(u), at the pole. To see this, suppose that the graph of f passes through the pole when, u � u0. Then f(u0) � 0. If f ¿(u0) 0, then Equation (3) reduces to, f ¿(u0) sin u0 � f(u0) cos u0, dy, sin u0, �, �, � tan u0, dx, f ¿(u0) cos u0 � f(u0) sin u0, cos u0

Page 28 :

10.4 Polar Coordinates, , 875, , This shows that u � u0 is a tangent line to the graph of r � f(u) at the pole (0, u0) ., The following summarizes this discussion., u � u0 is a tangent line to the graph of r � f(u) at the pole if f(u0) � 0 and, f ¿(u0) 0., , EXAMPLE 9 Consider the cardioid r � 1 � cos u of Example 6., a. Find the slope of the tangent line to the cardioid at the point where u � p>6., b. Find the points on the cardioid where the tangent lines are horizontal and where, the tangent lines are vertical., Solution, a. The slope of the tangent line to the cardioid r � 1 � cos u at any point P(r, u) is, given by, dr, sin u � r cos u, dy, (�sin u)(sin u) � (1 � cos u)cos u, du, �, �, dx, dr, (�sin u)(cos u) � (1 � cos u)sin u, cos u � r sin u, du, �, , (cos2 u � sin2 u) � cos u, cos 2u � cos u, ��, �2 sin u cos u � sin u, sin 2u � sin u, , At the point on the cardioid where u � p>6, the slope of the tangent line is, dy, `, dx u�p>6, , p, p, 1, 13, cosa b � cosa b, �, 3, 6, 2, 2, ��, ��, � �1, p, p, 13, 1, sina b � sina b, �, 3, 6, 2, 2, , b. Observe that dy>du � 0 if, cos 2u � cos u � 0, 2 cos u � cos u � 1 � 0, 2, , (2 cos u � 1)(cos u � 1) � 0, that is, if cos u � or cos u � �1. This gives, 1, 2, , u�, , p, , p, or, 3, , 5p, 3, , Next, dx>du � 0 if, sin 2u � sin u � 0, 2 sin u cos u � sin u � 0, sin u (2 cos u � 1) � 0, that is, if sin u � 0 or cos u � �12. This gives, u � 0,, , p,, , 2p, ,, 3, , or, , 4p, 3

Page 29 :

876, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, , In view of the remarks following Equation (3), we see that u � p>3 and, u � 5p>3 give rise to horizontal tangents. To investigate the candidate u � p,, where both dy>du and dx>du are equal to zero, we use l’Hôpital’s Rule. Thus,, lim�, , u→p, , ( 32 , π3 ), , dy, cos 2u � cos u, � � lim�, dx, u→p sin 2u � sin u, � � lim�, , 1, , (, , 1 2π, 2, 3, , ), , u→p, , �2 sin 2u � sin u, �0, 2 cos 2u � cos u, , Similarly, we see that, , (0, π), 0, , (2, 0), 2, , ( 12 , 4π3 ), , lim, , u→p�, , Therefore, u � p also gives rise to a horizontal tangent. Thus, the horizontal tangent lines occur at, , �1, , 1 32, p3 2 ,, , ( 32 , 5π3 ), FIGURE 16, The horizontal and vertical tangents to, the graph of r � 1 � cos u, , ¨ �π, 4, (y � x), , ¨ � 3π, 4, (y � �x), , dy, �0, dx, , (0, p) , and, , 1 32, 5p3 2, , The vertical tangent lines occur at u � 0, 2p>3, and 4p>3. The points are (2, 0),, 1 12, 2p3 2 , and 1 12, 4p3 2 . These tangent lines are shown in Figure 16., , EXAMPLE 10 Find the tangent lines of r � cos 2u at the origin., Solution, , Setting f(u) � cos 2u � 0, we find that, 2u �, , p, ,, 2, , 3p, ,, 2, , 5p, , or, 2, , 7p, 2, , u�, , p, ,, 4, , 3p, ,, 4, , 5p, ,, 4, , 7p, 4, , or, , FIGURE 17, The tangent lines to the graph of, r � cos 2u at the origin, , 10.4, , or, , Next, we compute f ¿(u) � �2 sin 2u. Since f ¿(u) 0 for each of these values of u, we, see that u � p>4 and u � 3p>4 (that is, y � x and y � �x) are tangent lines to the, graph of r � cos 2u at the pole (see Figure 17)., , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, , 1. Let P(r, u) be a point in the plane with polar coordinates r, and u. Find all possible representations of P(r, u)., 2. Suppose that P has representation (r, u) in polar coordinates, and (x, y) in rectangular coordinates. Express (a) x and y in, terms of r and u and (b) r and u in terms of x and y., 3. Explain how you would determine whether the graph of, r � f(u) is symmetric with respect to (a) the polar axis,, (b) the vertical line u � p>2, and (c) the pole., , 4. Suppose that r � f(u), where f is differentiable., a. Write an expression for dy>dx., b. How do you find the points on the graph of r � f(u), where the tangent lines are horizontal and where the tangent lines are vertical?, c. How do you find the tangent lines to the graph of, r � f(u) (if they exist) at the pole?

Page 30 :

10.4 Polar Coordinates, , 10.4, , 877, , EXERCISES, , In Exercises 1–8, plot the point with the polar coordinates. Then, find the rectangular coordinates of the point., , 49. r � 4(1 � sin u), , 50. r � 3 � 3 cos u, 52. r � �3 sec u, , 1. 1 4, p4 2, , 2. 1 2, p6 2, , 51. r � 2 csc u, , 5. 1 �12, p4 2, , 6. 1 �1, p3 2, , 54. r �, , 3. 1 4, 3p, 2 2, , 53. r � u,, , 4. (6, 3p), , 7. 1 �4, �3p, 4 2, , 8. 1 5, �5p, 6 2, , In Exercises 9–16, plot the point with the rectangular coordinates. Then find the polar coordinates of the point taking r � 0, and 0 u � 2p., , 1, u, , u � 0 (spiral), (spiral), , 55. r � eu,, , u � 0 (logarithmic spiral), , 1, 56. r 2 �, u, , (lituus), , 57. r 2 � 4 sin 2u (lemniscate), , 9. (2, 2), , 10. (1, �1), , 58. r � 1 � 2 cos u (limaçon), , 11. (0, 5), , 12. (3, �4), , 59. r � 3 � 2 sin u, , 13. (�13, �13), , 14. (2 13, �2), , 60. r � sin 2u (four-leaved rose), , 15. (5, �12), , 16. (3, �1), , 61. r � sin 3u (three-leaved rose), , In Exercises 17–24, sketch the region comprising points whose, polar coordinates satisfy the given conditions., 17. r � 1, , 18. r � 1, , 19. 0, , r, , 2, , 20. 1, , r�2, , 21. 0, , u, , p, 4, , 22. 0, , r, , 23. 1, , r, , 3,, , 24. 2 � r � 4,, , �p6, , u, , 3,, , 0, , u, , p, 3, , p, 6, , �p2 � u � p2, , (limaçon), , 62. r � 2 cos 4u (eight-leaved rose), 63. r � 4 sin 4u, , (eight-leaved rose), , 64. r � 2 sin 5u, , (five-leaved rose), , In Exercises 65–72, find the slope of the tangent line to the, curve with the polar equation at the point corresponding to the, given value of u., 65. r � 4 cos u, u �, , In Exercises 25–32, convert the polar equation to a rectangular, equation., 25. r cos u � 2, , 26. r sin u � �3, , 27. 2r cos u � 3r sin u � 6, , 28. r sin u � 2r cos u, , 29. r 2 � 4r cos u, , 30. r 2 � sin 2u, , 1, 31. r �, 1 � sin u, , 3, 32. r �, 4 � 5 cos u, , In Exercises 33–38, convert the rectangular equation to a polar, equation., , 67. r � sin u � cos u,, 68. r � 1 � 3 cos u,, , p, 3, u�, u�, , 69. r � u, u � p, 71. r 2 � 4 cos 2u, u �, , u�, , p, 4, , 70. r � sin 3u, u �, , p, 3, , 66. r � 3 sin u,, , p, 6, , p, 4, , p, 2, , 72. r � 2 sec u,, , u�, , p, 4, , 33. x � 4, , 34. x � 2y � 3, , In Exercises 73–78, find the points on the curve with the given, polar equation where the tangent line is horizontal or vertical., , 35. x 2 � y 2 � 9, , 36. x 2 � y 2 � 1, , 73. r � 4 cos u, , 74. r � sin u � cos u, , 37. xy � 4, , 38. y 2 � x 2 � 42x 2 � y 2, , 75. r � sin 2u, , 76. r 2 � 4 cos 2u, , 77. r � 1 � 2 cos u, , 78. r � 1 � sin u, , In Exercises 39–64, sketch the curve with the polar equation., 39. r � 3, , 40. r � �2, , p, 41. u �, 3, , p, 42. u � �, 6, , 43. r � 3 cos u, , 44. r � �4 sin u, , 45. r � 3 cos u � 2 sin u, , 46. r � 2 sin u � 4 cos u, , 47. r � 1 � cos u, , 48. r � 1 � sin u, , 79. Show that the rectangular equation, x 4 � 2x 3 � 2x 2y 2 � 2xy 2 � y 2 � y 4 � 0, is an equation of the cardioid with polar equation, r � 1 � cos u., 80. Show that the polar equation r � a sin u � b cos u, where a, and b are nonzero, represents a circle. What are the center, and radius of the circle?, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login.

Page 31 :

878, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, , 81. a. Show that the distance between the points with polar, coordinates (r1, u1) and (r2, u2) is given by, , In Exercises 85–92, use a graphing utility to plot the curve with, the polar equation., 85. r � cos u(4 sin2 u � 1), 0, , d � 2r 21 � r 22 � 2r1r2 cos(u1 � u2), , 86. r � 3 sin u cos u, 0, , b. Find the distance between the points with polar coordip, nates 1 4, 2p, 3 2 and 1 2, 3 2 ., , 82. Show that the curves with polar equations r � a sin u and, r � a cos u intersect at right angles., , u, 87. r � 0.3c1 � 2 sina b d , 0, 2, (nephroid of Freeth), 1 � 10 cos u, , 0, 1 � 10 cos u, , 83. a. Plot the graphs of the cardioids r � a(1 � cos u) and, r � a(1 � cos u)., b. Show that the cardioids intersect at right angles except at, the pole., , 88. r �, , 84. Let c be the angle between the radial line OP and the tangent line to the curve with polar equation r � f(u) at P (see, the figure). Show that, , 90. r 2 �, , du, tan c � r, dr, Hint: Observe that c � f � u. Then use the trigonometric identity, tan(a � b) �, , sin u � 3.6 cos u, 2, , 0, , u � 2p (hippopede curve), , 2, , sin2 u � cos2 u, , 91. r �, , 0.1, , 0, cos 3u, , 92. r �, , sin u, , �6p, u, , u�p, , , 0, , u � 2p, , (devil’s curve), , (epi-spiral), , u � 6p, , (cochleoid), , 93. If P(r1, u1) and P(r2, u2) represent the same point in polar, coordinates, then r1 � r2., , r � f(¨), , 94. If P(r1, u1) and P(r2, u2) represent the same point in polar, coordinates, then u1 � u2., , �, , 95. The graph of r � f(u) has a horizontal tangent line at a, point on the graph if dy>du � 0, where y � f(u)sin u., , P, ƒ, x, , O, , 10.5, , u � 2p, , 89. r 2 � 0.8(1 � 0.8 sin2 u),, 1, 4, , u � 4p, , In Exercises 93–95, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why it is true. If it is false, give an, example to show why it is false., , tan a � tan b, 1 � tan a tan b, , y, , ¨, , u � 2p, , u � 2p, , 2, , Areas and Arc Lengths in Polar Coordinates, In this section we see how the use of polar equations to represent curves such as lemniscates and cardioids will simplify the task of finding the areas of the regions enclosed, by these curves as well as the lengths of these curves., , Areas in Polar Coordinates, r, , ¨, , A, , To develop a formula for finding the area of a region bounded by a curve defined by, a polar equation, we need the formula for the area of a sector of a circle, A�, , 2π, , FIGURE 1, The area of a sector of a, circle is A � 12 r 2u., , 1 2, r u, 2, , (1), , where r is the radius of the circle and u is the central angle measured in radians. (See, Figure 1.) This formula follows by observing that the area of a sector is u>(2p) times, that of the area of a circle; that is,, A�, , u, 1, ⴢ pr 2 � r 2u, 2p, 2

Page 32 :

10.5 Areas and Arc Lengths in Polar Coordinates, , 879, , Now let R be a region bounded by the graph of the polar equation r � f(u) and, the rays u � a and u � b, where f is a nonnegative continuous function and, 0 b � a � 2p, as shown in Figure 2a. Let P be a regular partition of the interval, [a, b]:, a � u0 � u1 � u2 � p � un � b, ¨�∫, , ¨�∫, r � f(¨), , ¨ � ¨k*, ¨ � ¨k �1, , Ψ, , ¨�å, , ¨�å, , R, , FIGURE 2, , rk* � f (¨k* ), ¨ � ¨k, , 0, , 0, , (a) The region R, , (b) The k th subregion, , The rays u � uk divide R into n subregions R1, R2, p , Rn of area ⌬A1, ⌬A2, p ,, ⌬An, respectively. If we choose u*k in the interval [uk�1, uk], then the area of ⌬Ak of the, kth subregion bounded by the rays u � uk�1 and u � uk is approximated by the sector, of a circle with central angle, ⌬u �, , b�a, n, , and radius f(u*k ) (highlighted in Figure 2b). Using Equation (1), we have, ⌬Ak ⬇, , 1, [f(u*k )]2 ⌬u, 2, , Therefore, an approximation of the area A of R is, n, n, 1, A � a ⌬Ak ⬇ a [ f(u*k )]2 ⌬u, k�1, k�1 2, , (2), , But the sum in Equation (2) is a Riemann sum of the continuous function 12 f 2 over the, interval [a, b]. Therefore, it is true, although we will not prove it here, that, n, 1, A � lim a [ f(u*k )]2 ⌬u �, n→⬁ k�1 2, , 冮, , b, , a, , 1, [ f(u)]2 du, 2, , THEOREM 1 Area Bounded by a Polar Curve, Let f be a continuous, nonnegative function on [a, b] where 0 b � a � 2p., Then the area A of the region bounded by the graphs of r � f(u), u � a, and, u � b is given by, A�, , 冮, , b, , a, , 1, [f(u)]2 du �, 2, , 冮, , b, , a, , 1 2, r du, 2, , Note When you determine the limits of integration, keep in mind that the region R, is swept out in a counterclockwise direction by the ray emanating from the origin, starting at the angle a and terminating at the angle b.

Page 33 :

880, , Chapter 10 Conic Sections, Plane Curves, and Polar Coordinates, π, ¨�4, , �2, , 2, , EXAMPLE 1 Find the area of the region enclosed by the lemniscate r 2 � 4 cos 2u., , This lemniscate has rectangular equation x 4 � 2x 2y 2 � 4x 2 � 4y 2 � y 4 � 0, as you, can verify., Solution The lemniscate is shown in Figure 3. Making use of symmetry, we see that, the required area A is four times that of the area swept out by the ray emanating from, the origin as u increases from 0 to p>4. In other words,, , FIGURE 3, The region enclosed by the lemniscate, r 2 � 4 cos 2u, , A�4, , 冮, , 0, , p>4, , 1 2, r du � 8, 2, , � C4 sin 2uD 0, , p>4, , 冮, , p>4, , cos 2u du, , 0, , �4, , EXAMPLE 2 Find the area of the region enclosed by the cardioid r � 1 � cos u., Solution The graph of the cardioid r � 1 � cos u, sketched previously in Example 6, in Section 10.4, is reproduced in Figure 4. Observe that the ray emanating from the, origin sweeps out the required region exactly once as u increases from 0 to 2p. Therefore, the required area A is, , 1, , 2, , A�, , �1, , 冮, , 2p, , 0, , 1 2, r du �, 2, , �, , FIGURE 4, The region enclosed by the, cardioid r � 1 � cos u, , �, �, �, , 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, , 冮, , 2p, , 冮, , 2p, , 冮, , 2p, , 冮, , 2p, , 0, , 1, (1 � cos u)2 du, 2, , (1 � 2 cos u � cos2 u) du, , 0, , 0, , 0, , a1 � 2 cos u �, , 1 � cos 2u, b du, 2, , 3, 1, a � 2 cos u � cos 2ub du, 2, 2, , 2p, 1 3, 1, 3, c u � 2 sin u � sin 2ud � p, 2 2, 4, 2, 0, , EXAMPLE 3 Find the area inside the smaller loop of the limaçon r � 1 � 2 cos u., ¨ � 2π, 3, , r � 1 � 2 cos ¨, , ¨�0, , Solution We first sketch the limaçon r � 1 � 2 cos u (Figure 5). Observe that the, region of interest is swept out by the ray emanating from the origin as u runs from, 2p>3 to 4p>3. We can also take advantage of symmetry by observing that the required, area is double the area of the smaller loop lying below the polar axis. Since this region, is swept out by the ray emanating from the origin as u runs from 2p>3 to p, we see, that the required area is, A�2, , 冮, , p, , 2p>3, , ¨ � 4π, 3, , FIGURE 5, The limaçon r � 1 � 2 cos u, , �, , 冮, , p, , 冮, , p, , 冮, , p, , 1 2, r du �, 2, , 冮, , p, , r 2 du, , 2p>3, , (1 � 2 cos u)2 du, , 2p>3, , �, , (1 � 4 cos u � 4 cos2 u) du, , 2p>3, , �, , 2p>3, , c1 � 4 cos u � 4a, , 1 � cos 2u, b d du, 2

Page 34 :