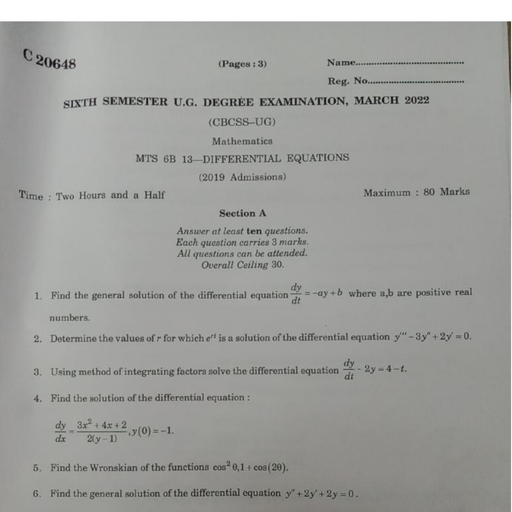

Page 1 :

730, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , 9.1, , Sequences, An idealized superball is dropped from a height of 1 m onto a flat surface. Suppose, that each time the ball hits the surface, it rebounds to two thirds of its previous height., If we let a1 denote the initial height of the ball, a2 denote the maximum height attained, on the first rebound, a3 denote the maximum height attained on the second rebound,, and so on, then we have, 2, a2 � ,, 3, , a1 � 1,, , 4, a3 � ,, 9, , a4 �, , 8, ,, 27, , p, , (See Figure 1.) This array of numbers, a1, a2, a3, p , is an example of an infinite, sequence, or simply a sequence. If we define the function f by f(x) � 1 23 2 x�1 and allow, x to take on the positive integral values x � 1, 2, 3, p , n, p , then we see that the, sequence a1, a2, a3, p , may be viewed as the functional values of f at these numbers., Thus,, f(1) � 1, , 2, 3, , f(2) �, , ⏐, ↓, a1, , f(3) �, , ⏐, ↓, a2, , 4, 9, , 2 n�1, f(n) � a b, 3, , p, , ⏐, ↓, a3, , ⏐, ↓, an, , p, , p, , y (m), 1, 2, 3, 4, 9, 8, 27, , FIGURE 1, The ball rebounds to two, thirds of its previous height, upon hitting the surface., , 0, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 5, , n, , This discussion motivates the following definition., , DEFINITION Sequence, A sequence {an} is a function whose domain is the set of positive integers. The, functional values a1, a2, a3, p , an, p are the terms of the sequence, and the, term an is called the nth term of the sequence., , Notes, ⬁, 1. The sequence {an} is also denoted by {an}n�1, ., 2. Sometimes it is convenient to begin a sequence with ak. In this case the sequence, ⬁, is {an}n�k, , and its terms are ak, ak�1, ak�2, p , an, p ., , EXAMPLE 1 List the terms of the sequence., a. e, , n, f, n�1, , b. e, , 1n, 2, , f, n�1, , ⬁, c. {(�1)n 1n � 2}n�2, , d. esin, , np ⬁, f, 3 n�0

Page 2 :

9.1, , Sequences, , 731, , Solution, a. Here, an � f(n) �, a1 � f(1) �, , n, . Thus,, n�1, , 1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, � , a2 � f(2) �, � , a3 � f(3) �, � , p, 1�1, 2, 2�1, 3, 3�1, 4, , and we see that the given sequence can be written as, e, b. e, , 1n, n�1, , 2, , f�e, , n, 1 2 3 4, n, f � e , , , ,p,, , pf, n�1, 2 3 4 5, n�1, , 11 12 13 14, 1n, , 1 , 2 , 3 , p , n�1 , pf, 0, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, , ⬁, c. {(�1)n 1n � 2}n�2, � {(�1)2 10, (�1)3 11, (�1)4 12,, , (�1) 5 13, p , (�1)n 1n � 2, p}, � {0, � 11, 12, � 13, p , (�1)n 1n � 2, p}, Notice that n starts from 2 in this example. (See Note 2 on page 730.), d. esin, , np ⬁, p, 2p, 3p, 4p, 5p, np, f, � esin 0, sin , sin, , sin, , sin, , sin, , p , sin, , pf, 3 n�0, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3, � e0,, , 13 13, 13 13, np, ,, , 0, �, ,�, , p , sin, , pf, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3, , Once again, refer to Note 2., We can often determine the nth term of a sequence by studying the first few terms, of the sequence and recognizing the pattern that emerges., , EXAMPLE 2 Find an expression for the nth term of each sequence., a. e2,, , 1 1 1, b. e1, , , , pf, 8 27 64, , 3, 4, 5, ,, ,, , pf, 12 13 14, , 1 1, 1, c. e1, � , , � , pf, 2 3, 4, , Solution, a. The terms of the sequence may be written in the form, a1 �, , 1�1, ,, 11, , a2 �, , 2�1, ,, 12, , from which we see that an �, , a3 �, , 3�1, ,, 13, , a4 �, , 4�1, ,, 14, , p, , n�1, ., 1n, , b. Here,, a1 �, so an �, , 1, 1, , 3, , ,, , a2 �, , 1, 2, , 3, , ,, , a3 �, , 1, 3, , 3, , ,, , a4 �, , 1, 43, , ,, , p, , 1, , ., n3, c. Note that (�1)r is equal to 1 if r is an even integer and �1 if r is an odd integer., Using this result, we obtain, a1 �, , (�1)0, ,, 1, , a2 �, , (�1)1, ,, 2, , a3 �, , (�1)2, ,, 3, , We conclude that the nth term is an � (�1)n�1>n., , a4 �, , (�1)3, ,, 4, , p

Page 3 :

732, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , Some sequences are defined recursively; that is, the sequence is defined by specifying the first term or the first few terms of the sequence and a rule for calculating, any other term of the sequence from the preceding term(s)., , EXAMPLE 3 List the first five terms of the recursively defined sequence a1 � 2,, a2 � 4, and an�1 � 2an � an�1 for n � 2., Solution The first two terms of the sequence are given as a1 � 2 and a2 � 4. To find, the third term of the sequence, we put n � 2 in the recursion formula to obtain, a3 � 2a2 � a1 � 2 ⴢ 4 � 2 � 6, Next, putting n � 3 and n � 4 in succession in the recursive formula gives, a4 � 2a3 � a2 � 2 ⴢ 6 � 4 � 8, , and, , a5 � 2a4 � a3 � 2 ⴢ 8 � 6 � 10, , Since a sequence is a function, we can draw its graph. The graphs of the sequences, {n>(n � 1)} and {(�1)n} are shown in Figure 2. They are just the graphs of the functions f(n) � n>(n � 1) and t(n) � (�1)n for n � 1, 2, 3, p ., g(n), , f(n), , a4, a3, a2 a1, , a2, a4, a6, , y�1, , 1, , 1, , 0, 0, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 5, , 6, , 7, , a1, a3, a5, , n, , n, (a) The graph of n � 1, , {, , }, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 5, , 6, , 7, , n, , �1, , (b) The graph of {(�1)n}, , FIGURE 2, , Limit of a Sequence, If you examine the graph of the sequence {n>(n � 1)} sketched in Figure 2a, you will, see that the terms of the sequence seem to get closer and closer to 1 as n gets larger, and larger. In this situation we say that the sequence {n>(n � 1)} converges to the, limit 1, written, lim, , n→⬁, , n, �1, n�1, , In general, we have the following informal definition of the limit of a sequence., , DEFINITION Limit of a Sequence, A sequence {an} has the limit L, written, lim an � L, , n→⬁, , if an can be made as close to L as we please by taking n sufficiently large. If, lim n→⬁ an exists, we say that the sequence converges. Otherwise, we say that, the sequence diverges.

Page 4 :

9.1, , Sequences, , 733, , A more precise definition of the limit of a sequence follows., , DEFINITION (Precise) Limit of a Sequence, A sequence {an} converges and has the limit L, written, lim an � L, , n→⬁, , if for every e � 0 there exists a positive integer N such that 冟 an � L 冟 � e whenever n � N., , To illustrate this definition, suppose that a challenger selects an e � 0. Then we, must show that there exists a positive integer N such that all points (n, an) on the graph, of {an}, where n � N, lie inside a band of width 2e about the line y � L. (See Figure 3.), y, y�L��, y�L, y�L��, , L, , FIGURE 3, If n � N, then L � e � an � L � e, or, equivalently, 冟 an � L 冟 � e., , 0, , 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11, (N), , n, , To reconcile this definition with the intuitive definition of a limit, recall that e is, arbitrary. Therefore, by choosing e very small, the challenger ensures that an is “close”, to L. Furthermore, if corresponding to each choice of e, we can produce an N such that, n � N implies that 冟 an � L 冟 � e, then we have shown that an can be made as close to, L as we please by taking n sufficiently large., Notice that the definition of the limit of a sequence is very similar to the definition, of the limit of a function at infinity given in Section 3.5. This is expected, since the, only difference between a function f defined by y � f(x) on the interval (0, ⬁) and the, sequence {an} defined by an � f(n) is that n is an integer. (See Figure 4.) This observation tells us that we can often evaluate lim n→⬁ an by evaluating lim x→⬁ f(x), where, f is defined on (0, ⬁) and an � f(n)., y, an, , y � f(x), L, , FIGURE 4, The graph of {an} comprises, the points (n, f(n)) that lie, on the graph of y � f(x) ., , 0, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 5, , 6, , 7, , 8, , 9 10 11 12 13, , x, n

Page 5 :

734, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , THEOREM 1, If lim x→⬁ f(x) � L and {an} is a sequence defined by an � f(n), where n is a, positive integer, then lim n→⬁ an � L., You will be asked to prove Theorem 1 in Exercise 75., y, an, , EXAMPLE 4 Find lim, , n→⬁, , 3, , 1, if r � 0., nr, , Solution Since an � 1>n r, we choose f(x) � 1>x r, where x � 0. By Theorem 1 in, Section 3.5 we have, , 2, 1, , lim, , x→⬁, , 0, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4 x, n, , FIGURE 5, The graph of {1>n r} for n � 1, 2, 3, 4,, and r � 1. The graph of f(x) � 1>x r is, shown with a dashed curve., , 1, �0, xr, , Using Theorem 1 of this section, we conclude that, lim, , n→⬁, , 1, �0, nr, , (See Figure 5.), , !, , The converse of Theorem 1 is false. Consider, for example, the sequence, {sin np} � {0}. This sequence evidently converges to 0, since every term of the, sequence is 0. But lim x→⬁ sin px does not exist. (See Figure 6.), y, an, 1, , FIGURE 6, The graph of {sin np} for, n � 0, 1, 2, p , 10. The, graph of f(x) � sin px is, shown with a dashed curve., , 0, , 2, , 4, , 6, , 8, , 10 x, n, , �1, , The following limit laws for sequences are the analogs of the limit laws for functions studied in Section 1.2 and are proved in a similar manner., , THEOREM 2 Limit Laws for Sequences, Suppose that lim n→⬁ an � L and lim n→⬁ bn � M and that c is a constant. Then, 1. lim can � cL, n→⬁, , 2. lim (an, n→⬁, , bn) � L, , M, , 3. lim anbn � LM, n→⬁, , 4. lim, , n→⬁, , an, L, � , provided that bn, bn, M, , 0 and M, , 5. lim a pn � Lp, if p � 0 and an � 0, n→⬁, , 0

Page 6 :

9.1, , Sequences, , 735, , EXAMPLE 5 Determine whether the sequence converges or diverges., a. e, , n, f, n�1, , b. {(�1)n}, , Solution, a. Both the numerator and the denominator of n>(n � 1) approach infinity as n, approaches infinity. So their limits do not exist, and we cannot use Law 4 of, Theorem 2. But we can divide the numerator and denominator by n and then, apply Law 4 to evaluate the resulting limit. Thus,, lim, , n→⬁, , n, � lim, n � 1 n→⬁, , 1, 1, 1�, n, , �1, , and we conclude that the sequence converges to 1. (See Figure 2a.), b. The terms of the sequence are, �1, 1, �1, 1, p, The sequence evidently does not approach a unique number, and we conclude, that it diverges. (See Figure 2b.), , EXAMPLE 6 Find, a. lim, , n→⬁, , y, an, , ln n, n, , b. lim, , n→⬁, , en, n2, , Solution, a. Observe that both the numerator and the denominator of (ln n)>n approach infinity as n → ⬁ . Therefore, we may not use Law 4 of Theorem 2 directly. Since, an � f(n) � (ln n)>n, we consider the function f(x) � (ln x)>x. Using l’Hôpital’s, Rule, we find, , 0.5, 0.4, 0.3, 0.2, 0.1, 0, , 10, , 20, , lim, , 40 x, n, , 30, , FIGURE 7, The graph of {(ln n)>n} for n � 5, 10,, 15, p , 40. The graph of f(x) � (ln x)>x, is shown with a dashed curve., , x→⬁, , 1>x, ln x, 1, � lim, � lim � 0, x, x→⬁ 1, x→⬁ x, , Therefore, by Theorem 1 we conclude that, lim, , n→⬁, , (See Figure 7.), b. Once again both en and n 2 approach infinity as n → ⬁ . Choose f(x) � ex>x 2, and, use l’Hôpital’s Rule twice to find that, , y, an, 30, 25, 20, , lim, , x→⬁, , 15, , ex, x2, , � lim, , x→⬁, , ex, ex, � lim, �⬁, 2x x→⬁ 2, , from which we see that, , 10, 5, 0, , ln n, �0, n, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 5, , 6, , 7 x, n, , FIGURE 8, The graph of {en>n 2}. The graph of, f(x) � ex>x 2 is shown with a dashed, curve., , lim, , n→⬁, , en, n2, , �⬁, , and we conclude that the sequence {en>n 2} is divergent. (See Figure 8.), The Squeeze Theorem has the following counterpart for sequences. (The proof is, similar to that of the Squeeze Theorem and will be omitted.)

Page 7 :

736, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , THEOREM 3 Squeeze Theorem for Sequences, If there exists some integer N such that an bn, lim n→⬁ an � lim n→⬁ cn � L, then lim n→⬁ bn � L., , cn for all n � N and, , (See Figure 9.), an, cn, L, , bn, an, , FIGURE 9, The sequence {bn} is squeezed between, the sequences {an} and {cn}., , 0, , EXAMPLE 7 Find lim, , n→⬁, , n, , n!, , where n! (read “n factorial”) is defined by, nn, n! � n(n � 1)(n � 2) p 1, , Let an � n!>n n. The first few terms of {an} are, , Solution, , a1 �, , 1!, � 1,, 1, , a2 �, , 2!, 2, , 2, , �, , 2ⴢ1, ,, 2ⴢ2, , a3 �, , 3!, 3, , 3, , �, , 3ⴢ2ⴢ1, 3ⴢ3ⴢ3, , and its nth term is, an �, , n(n � 1) ⴢ p ⴢ 3 ⴢ 2 ⴢ 1, n n�1, 3 2 1, n!, � a ba, b ⴢ p ⴢ a ba ba b, n �, p, nⴢnⴢ ⴢnⴢnⴢn, n, n, n n n, n, , Therefore,, 0 � an, , 1, n, , Since lim n→⬁ 1>n � 0, the Squeeze Theorem implies that, lim an � lim, , n→⬁, , n→⬁, , n!, �0, nn, , The next theorem is an immediate consequence of the Squeeze Theorem., , THEOREM 4, If lim n→⬁ 冟 an 冟 � 0, then lim n→⬁ an � 0., , You are asked to prove Theorem 4 in Exercise 76., , 1, n

Page 8 :

9.1, , EXAMPLE 8 Find lim, , n→⬁, , Solution, , Sequences, , 737, , (�1)n, ., n, , Since, lim `, , n→⬁, , (�1)n, 1, ` � lim � 0, n, n→⬁ n, , we conclude by Theorem 4 that, lim, , n→⬁, , (�1)n, �0, n, , The graph of the sequence {(�1)n>n} confirms this result. (See Figure 10.), y, an, 2, , 1, , y � 1x, , a2, a4, a5, a3, a1, , FIGURE 10, The terms of the sequence, {(�1)n>n} oscillate between the, graphs of y � 1>x and y � �1>x., , 2, , 4, , 6, , 8, , 10 x, n, , y � � 1x, , �1, �2, , If we take the composition of a function f with a sequence {an}, we obtain another, sequence {f(an)}. The following theorem shows how to compute the limit of the latter. The proof will be given in Appendix B., , THEOREM 5, If lim n→⬁ an � L and the function f is continuous at L, then, lim f(an) � f( lim an) � f(L), , n→⬁, , Note, , n→⬁, , Compare this theorem with Theorem 4 in Section 1.4., , EXAMPLE 9 Find lim n→⬁ esin(1>n)., Solution, , Observe that esin(1>n) � f(an), where f(x) � ex and an � sin(1>n) . Since, lim sin, , n→⬁, , 1, �0, n, lim sin(1>n), , and f is continuous at 0, Theorem 5 gives lim n→⬁ esin(1>n) � en→⬁, , � e0 � 1.

Page 9 :

738, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , Bounded Monotonic Sequences, Up to now, the convergent sequences that we have dealt with had limits that are readily found. Sometimes, however, we need to show that a sequence is convergent even, if its precise limit is not readily found. Our immediate goal here is to find conditions, that will guarantee that a sequence converges. To do this, we need to make use of two, further properties of sequences., , DEFINITION Monotonic Sequence, A sequence {an} is increasing if, a1 � a2 � a3 � p � an � an�1 � p, and decreasing if, a1 � a2 � a3 � p � an � an�1 � p, A sequence is monotonic if it is either increasing or decreasing., , EXAMPLE 10 Show that the sequence e, Solution, , n, f is increasing., n�1, , Let an � n>(n � 1). We must show that an, , an�1 for all n � 1; that is,, , n�1, (n � 1) � 1, , n, n�1, or, , n�1, n�2, , n, n�1, , To show that this inequality is true, we obtain the following equivalent inequalities:, n(n � 2), n � 2n, 2, , 0, which is true for n � 1. Therefore, an, Alternative Solution, x>(x � 1). Since, f ¿(x) �, , (n � 1)(n � 1), , Cross-multiply., , n � 2n � 1, 2, , 1, an�1, so {an} is increasing., , Here, an � f(n) � n>(n � 1). So consider the function f(x) �, (x � 1)(1) � x(1), (x � 1), , 2, , �, , 1, (x � 1)2, , �0, , if, , x�0, , we see that f is increasing on (0, ⬁). Therefore, the given sequence is increasing., , EXAMPLE 11 Show that the sequence e n f is decreasing., n, e

Page 10 :

9.1, , Solution, , Sequences, , 739, , We must show that an � an�1 for n � 1; that is,, n, n�1, n �, e, en�1, nen�1 � (n � 1)en, ne � n � 1, , Divide both sides by en., , n(e � 1) � 1, which is true for all n � 1, so {n>en} is decreasing., Next, we explain what is meant by a bounded sequence., , DEFINITION Bounded Sequence, A sequence {an} is bounded above if there exists a number M such that, an, , for all n � 1, , M, , A sequence is bounded below if there exists a number m such that, m, , for all n � 1, , an, , A sequence is bounded if it is both bounded above and bounded below., , For example, the sequence {n} is bounded below by 0, but it is not bounded above., The sequence {n>(n � 1)} is bounded below by 12 and above by 1 and is therefore, bounded. (See Figure 2a.), A bounded sequence need not be convergent. For example, the sequence {(�1)n}, is bounded, since �1 (�1)n 1; but it is evidently divergent. (See Figure 2b.) Also,, a monotonic sequence need not be convergent. For example, the sequence {n} is increasing and evidently divergent. However, if a sequence is both bounded and monotonic,, then it must be convergent., , THEOREM 6 Monotone Convergence Theorem for Sequences, Every bounded, monotonic sequence is convergent., The plausibility of Theorem 6 is suggested by the sequence {n>(n � 1)} whose, graph is reproduced in Figure 11. This sequence is increasing and bounded above by, yn, , a4, a3, a2 a, 1, , FIGURE 11, The increasing, bounded sequence, {n>(n � 1)} is convergent., , y�1, , 1, , 0, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 5, , 6, , 7, , n

Page 11 :

740, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , any number M � 1. Therefore, as n increases, the terms an approach a number (which, is no larger than M) from below. In this case the number is 1, which is also the limit, of this sequence. (A proof of Theorem 6 is given at the end of this section.), Theorem 6 can be used to find the limit of a convergent sequence indirectly, as, the next example shows. It will also play an important role in infinite series (Sections 9.2–9.9)., 2n, n!, , EXAMPLE 12 Show that e f is convergent and find its limit., Solution, a1 � 2,, , Here, an � 2n>n!. The first few terms of the sequence are, a2 � 2,, , a3 ⬇ 1.333333,, , a6 ⬇ 0.088889,, , a4 ⬇ 0.666667,, , p,, , a5 ⬇ 0.266667,, , a10 ⬇ 0.000282, , These terms suggest that the sequence is decreasing from n � 2 onward. To prove this,, we compute, an�1, an, , 2n�1, (n � 1)!, 2n�1n!, 2n!, 2, �, � n, �, �, n, 2, 2 (n � 1)!, (n � 1)n!, n�1, n!, , (1), , So, an�1, an, , 1, , if n � 1, , Thus, an�1 an if n � 1, and this proves the assertion. Since all of the terms of the, sequence are positive, {an} is bounded below by 0. Therefore, the sequence is decreasing and bounded below, and Theorem 6 guarantees that it converges to a nonnegative, limit L., To find L, we first use Equation (1) to write, an�1 �, , 2, an, n�1, , (2), , Since lim n→⬁ an � L, we also have lim n→⬁ an�1 � L. Taking the limit on both sides, of Equation (2) and using Law (3) for limits of sequences, we obtain, L � lim an�1 � lim a, n→⬁, , n→⬁, , 2, 2, an b � lim, ⴢ lim an � 0 ⴢ L � 0, n�1, n→⬁ n � 1 n→⬁, , We conclude that lim n→⬁ 2n>n! � 0., Alternative Solution, a2 �, , Observe that, , 2ⴢ2, 2ⴢ2ⴢ2, 2, 2ⴢ2ⴢ2ⴢ2, 2 2, 2 2, � 2, a3 �, � 2a b , a4 �, � a b a b2 � 2a b ,, 2ⴢ1, 3ⴢ2ⴢ1, 3, 4ⴢ3ⴢ2ⴢ1, 4 3, 3, a5 �, , 2ⴢ2ⴢ2ⴢ2ⴢ2, 2 2 2, 2 3, � a b a b a b2 � 2a b, 5ⴢ4ⴢ3ⴢ2ⴢ1, 5 4 3, 3, , and, an �, , 2ⴢ2ⴢ2ⴢpⴢ2, 2 n�2, �, 2a, b, n ⴢ (n � 1) ⴢ (n � 2) ⴢ p ⴢ 1, 3

Page 12 :

9.1, , Sequences, , 741, , Therefore, 2 n�2, 0 � an � 2a b, 3, , Since lim n→⬁ 1 23 2 n�2 � 0, the Squeeze Theorem gives the desired result., The next example contains some important results that we will derive here using, the Squeeze Theorem. (You will also be asked to demonstrate their validity using the, properties of exponential functions in Exercise 77.), , EXAMPLE 13 Show that lim n→⬁ r n � 0 if 冟 r 冟 � 1., Solution If r � 0, then each term of the sequence {r n} is 0, and the sequence converges to 0. Now suppose that 0 � 冟 r 冟 � 1. Then 1> 冟 r 冟 is greater than 1. So there exists, a positive number p such that, 1, �1�p, 冟r冟, Using the Binomial Theorem, we have, (1 � p)n � 1 � np �, , n(n � 1) 2 p, p � � p n � np, 2!, , Thus,, 0 � 冟 r 冟n �, , 1, 1, �, np, (1 � p)n, , But, lim, , n→⬁, , 1, �0, np, , so by the Squeeze Theorem, lim 冟 r 冟n � 0, , n→⬁, , Finally, using Theorem 4, we conclude that lim n→⬁ r n � 0., If r � 1, then r n � 1 for all n, and the sequence {r n} evidently converges to 1. If, r � �1, then the sequence {r n} � {(�1)n} is divergent. (See Example 5b.) If 冟 r 冟 � 1,, then 冟 r 冟 � 1 � p for some positive number p. Using the Binomial Theorem again, we, have, 冟 r 冟n � (1 � p)n � np, Since p � 0, lim n→⬁ np � ⬁ . This shows that {r n} diverges if 冟 r 冟 � 1., A summary of these results follows., Properties of the Sequence {r n}, The sequence {r n} converges if �1 � r, lim r n � e, , n→⬁, , It diverges for all other values of r., , 1 and, , 0 if �1 � r � 1, 1 if r � 1

Page 13 :

742, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , Proof of Theorem 6, The proof of Theorem 6 depends on the Completeness Axiom for the real number system, which states that every nonempty set S of real numbers that is bounded above has, a least upper bound. Thus, if x M for all x in S, then there must be a real number b, such that b is an upper bound of S (x b for all x 僆 S), and if N is any upper bound, of S, then N � b. For example, if S is the interval (�2, 3), then the number 4 (or any, number greater than 3) is an upper bound of S and 3 is the least upper bound of S. As, a consequence of this axiom, it can be shown that every nonempty set of real numbers, that is bounded below has a greatest lower bound. The Completeness Axiom merely, states that the real number line has no gaps or holes., , PROOF Suppose that {an} is an increasing sequence. Since {an} is bounded, the set, S � {an 冟 n � 1} is bounded above, and by the Completeness Axiom it has a least upper, bound L. (See Figure 12.) We claim that L is the limit of the sequence., an, L, an, L��, , a3, a2, a1, 0, , FIGURE 12, An increasing sequence bounded above, must converge to its least upper bound., , 1, , 2, , 3, N, , N�1, N�2, , n, , To show this, let e � 0 be given. Then L � e is not an upper bound of S (since, L is the least upper bound of S). Therefore, there exists an integer N such that, aN � L � e. But the sequence is increasing, so an � aN for every n � N. In other, words, if n � N, we have an � L � e. Since an L,, 0, , L � an � e, , This shows that, 冟 L � an 冟 � e, whenever n � N, so lim n→⬁ an � L., The proof is similar for the case in which {an} is decreasing, except that we use, the greatest lower bound instead., , 9.1, , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, , 1. Explain each of the following terms in your own words, and, give an example of each., a. Sequence, b. Convergent sequence, c. Divergent sequence, d. Limit of a sequence, , 2. Explain each of the following terms in your own words, and, give an example of each., a. Bounded sequence, b. Monotonic sequence

Page 14 :

9.1, , 9.1, , 33. an �, , 2n, 3 �1, , 34. an �, , 2n � 1, en, , n, , n�1, 2n � 1, , 2. an �, , (�1)n�12n, n�1, , 35. an � 1n � 1 � 1n, , 36. an �, , np, ,, en, , np, 2, , 4. an �, , 1 ⴢ 3 ⴢ 5 ⴢ p ⴢ (2n � 1), n!, , 2 1>n, 37. an � a1 � b, n, , 38. an �, , (�2)n, n!, , 3. an � sin, , 2n, (2n)!, , 39. an �, , sin2 n, 1n, , In Exercises 7–12, find an expression for the nth term of the, sequence. (Assume that the pattern continues.), , 40. an �, , 1 ⴢ 3 ⴢ 5 ⴢ p ⴢ (2n � 1), n!, , 3 4 5 6 7, 8. e , , , , , pf, 4 9 16 25 36, , 41. an �, , 5. an �, , 6. a1 � 2,, , 1 2 3 4 5, 7. e , , , , , pf, 2 3 4 5 6, , an�1 � 3an � 1, , 1, 1 1, 1, , pf, 9. e�1, , � , , �, 2, 6 24, 120, 10. {0, 2, 0, 2, 0, p}, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, ,, ,, ,, ,, ,pf, 11. e, 1ⴢ2 2ⴢ3 3ⴢ4 4ⴢ5 5ⴢ6, 1 1ⴢ3 1ⴢ3ⴢ5 1ⴢ3ⴢ5ⴢ7 1ⴢ3ⴢ5ⴢ7ⴢ9, ,, ,, ,, , pf, 12. e ,, 2 2 ⴢ 4 2 ⴢ 4 ⴢ 6 2 ⴢ 4 ⴢ 6 ⴢ 8 2 ⴢ 4 ⴢ 6 ⴢ 8 ⴢ 10, In Exercises 13–42, determine whether the sequence {an} converges or diverges. If it converges, find its limit., 2n, 13. an �, n�1, 15. an � 1 � 2(�1)n, n�1, 2n � 1, �, 17. an �, n, n2, 19. an �, , 2n 2 � 3n � 4, 3n � 1, 2, , 14. an � 1n � 1, (�1), , 16. an � 1 �, 18. an �, , n, , n 3>2, n2 � 1, , 20. an � (�1)n, 22. an �, , 23. an �, , 2n, 1n � 1, , 2 n, 24. an � 1 � a� b, e, , n � 2n 2>3, , 27. an � sin, 29. an �, , np, 2, , sin 1n, 1n, , 31. an � tanh n, , 2, , 22n 2 � 1, n, , n2, , �, , 3, , n2, , In Exercises 43–48, (a) graph the sequence {an} with a graphing, utility, (b) use your graph to guess at the convergence or divergence of the sequence, and (c) use the properties of limits to, verify your guess and to find the limit of the sequence if it, converges., 43. an �, , n�1, n�2, , 44. an � (�1)n, , 45. an �, , n!, nn, , 46. an � 2 tan�1 a, , 47. an � n sin, , 30. an � tan�1 n 2, 32. an �, , ln n 2, 1n, , n�1, b, n�3, , 49. Evaluate, , lim, , n→⬁, , 1 9, 1 � a1 � b, n, 1, 1 � a1 � b, n, , Hint: Use Theorem 1., , 50. Evaluate, lim na1 �, , 26. an � cos np � 2, np, b, 2n � 1, , 2n � 1, n�3, , 2 n, 48. an � a1 � b, n, , 1, n, , n→⬁, , 28. an � sina, , p�0, , n, �p� 2, n, 1�2�3�p�n, n, �, 42. an �, n�2, 2, �, , n�2, 3n � 1, , 2 � (�1)n, n, , n 1>2 � n 1>3, , 1, , n2, , 2n 2 � 1, , 21. an �, , 25. an �, , 743, , EXERCISES, , In Exercises 1–6, write the first five terms of the sequence {an}, whose nth term is given., 1. an �, , Sequences, , 7, , B, , 1, 1� b, n, , Hint: Use Theorem 1., , In Exercises 51–58, determine whether the sequence {an} is, monotonic. Is the sequence bounded?, 51. an �, , 3, 2n � 5, , 53. an � 3 �, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login., , 1, n, , 52. an �, , 2n, n�1, , 54. an � 2 �, , (�1)n, n

Page 15 :

744, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , 55. an �, , sin n, n, , 56. an � tan�1 n, , 57. an �, , n, 2n, , 58. an �, , ln n, n, , 59. Compound Interest If a principal of P dollars is invested in, an account earning interest at the rate of r per year compounded monthly, then the accumulated amount An at the, end of n months is, r n, An � Pa1 � b, 12, a. Write the first six terms of the sequence {An} if, P � 10,000 and r � 0.105. Interpret your results., b. Does the sequence {An} converge or diverge?, 60. Quality Control Half a percent of the microprocessors manufactured by Alpha Corporation for use in regulating fuel, consumption in automobiles are defective. It can be shown, that the probability of finding at least one defective microprocessor in a random sample of n microprocessors is, f(n) � 1 � (0.995)n. Consider the sequence {an} defined by, an � f(n) ., a. Write the terms a10, a100, and a1000., b. Evaluate lim n→⬁ an, and interpret your result., 61. Annuities An annuity is a sequence of payments made at, regular intervals. Suppose that a sum of $200 is deposited, at the end of each month into an account earning interest, at the rate of 12% per year compounded monthly. Then the, amount on deposit (called the future value of the annuity) at, the end of the nth month is f(n) � 20,000[(1.01) n � 1]., Consider the sequence {an} defined by an � f(n)., a. Find the 24th term of the sequence {an}, and interpret, your result., b. Evaluate lim n→⬁ an, and interpret your result., 62. Continuously Compounded Interest If P dollars is invested in an, account paying interest at the rate of r per year compounded, m times per year, then the accumulated amount at the end, of t years is, Am � Pa1 �, , r mt, b, m, , m � 1, 2, 3, p, , a. Find the limit of the sequence {Am}., b. Interpret the result in part (a)., Note: In this situation, interest is said to be compounded, , 64. Define the sequence {an} recursively by a0 � 2 and, an�1 � 1an for n � 1., n, a. Show that an � 21>2 ., b. Evaluate lim n→⬁ an., c. Verify the result of part (b) graphically., 65. Newton’s Method Suppose that A � 0. Applying Newton’s, method to the solution of the equation x 2 � A � 0 leads to, the sequence {x n} defined by, x n�1 �, , 1, A, ax n � b, xn, 2, , a. Show that if L � lim n→⬁ x n exists, then L � 1A., Hint: lim x n�1 � L, n→⬁, , b. Find 15 accurate to four decimal places., 66. Finding the Roots of an Equation Suppose that we want to find a, root of f(x) � 0. Newton’s method provides one way of, finding it. Here is another method that works under suitable, conditions., a. Write f(x) � 0 in the form x � t(x), where t is continuous. Then generate the sequence {x n} by the recursive, formula x n�1 � t(x n), where x 0 is arbitrary., b. Show that if the sequence {x n} converges to a number r,, then r is a solution of f(x) � 0., Hint: lim x n�1 � r, n→⬁, , c. Use this method to find the root of f(x) � 3x 3 � 9x � 2, (accurate to four decimal places) that lies in the interval, (0, 1)., Hint: Write 3x 3 � 9x � 2 � 0 in the form x � 19 (3x 3 � 2). Take, x 0 � 0., , 67. A Floating Object A sphere of radius 1 ft is made of wood that, has a specific gravity of 23. If the sphere is placed in water, it, sinks to a depth of h ft. It can be shown that h satisfies the, equation, h3 � 3h2 �, , Hint: Show that the equation can be written in the form, h � 13 23h3 � 8., , 68. Find the limit of the sequence, , 5 12, 22 12, 322212, p 6, n�1)>2n, , c. What is the accumulated amount at the end of 3 years if, $1000 is invested in an account paying interest at the rate, of 10% per year compounded continuously?, 2 3n, 63. Find the limit of the sequence e a1 � b f . Confirm your, n, results visually by plotting the graph of, 2 3x, f(x) � a1 � b, x, , 8, �0, 3, , Use the method described in Exercise 66 to find h accurate, to three decimal places., , Hint: Show that an � 2(2, , continuously., , x0 � 0, , n, , � 21�1>2 ., , 69. Consider the sequence {an} defined by a1 � 12 and, an � 12 � an�1 for n � 2. Assuming that the sequence, converges, find its limit., Note: Using the principle of mathematical induction, it can be, shown that {an} is increasing and bounded by 2 and, hence, by, Theorem 6 is convergent.

Page 16 :

9.1, 70. Show that if lim n→⬁ a2n � L and lim n→⬁ a2n�1 � L, then, lim n→⬁ an � L., 71. Let the sequence {an} be defined by, an � 1 �, , 1, 2, , 2, , �, , Hint:, , 1, n2, , �, , 1, �p� 2, 3, n, , lim an �, , n→⬁, , 2, , 1, 1, 1, �, � , for n � 2, n(n � 1), n�1, n, , c. Using the results of parts (a) and (b), what can you, deduce about the convergence of {an}?, , 745, , 78. Fibonacci Sequence The Fibonacci sequence {Fn} is defined, by F1 � 1, F2 � 1, and Fn�1 � Fn � Fn�1 for n � 2. Let, an � Fn�1>Fn. Assuming that {an} is convergent, show that, , 1, , a. Show that {an} is increasing., b. Show that {an} is bounded above by establishing that, an � 2 � 1>n for n � 2., , Sequences, , 1, (1 � 15), 2, , Hint: First, show that an�1 � 1 � 1>an�2. Then use the fact that if, lim n→⬁ an � L, then lim n→⬁ an�2 � lim n→⬁ an�1 � L., , Note: The number 12 (1 � 15), which is approximately 1.6, has the, following special property: A picture with a ratio of width to height, equal to this number is especially pleasing to the eye. The ancient, Greeks used this “golden” ratio in designing their beautiful temples, and public buildings, such as the Parthenon., , 72. Let the sequence {an} be defined by, 1, 1, 1, �p� n, � 2, 2�1, 2 �n, 2 �2, , a. Show that {an} is increasing., b. Show that {an} is bounded above., c. Using the results of parts (a) and (b), what can you, deduce about the convergence of {an}?, 73. Let the sequence {an} be defined by, a1 �, , a0, ,, 2 � a0, , a2, a3 �, ,, 2 � a2, , p,, , a2 �, , a1, ,, 2 � a1, , an�1, an �, ,, 2 � an�1, , The front of the Parthenon has a ratio of width to, height that is approximately 1.6 to 1., p, , where an � 0., a. Show that {an} is convergent., b. Find the limit of {an}., lim 1a � 1, , n→⬁, , In Exercises 79–86, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why it is true. If it is false, explain why, or give an example to show why it is false., 79. If {an} and {bn} are divergent, then {an � bn} is divergent., , 74. Use the Squeeze Theorem for Sequences to prove that, n, , The Gallery Collection/Corbis, , an �, , a�0, , Hint: For n sufficiently large, 1>n � a � n., , 75. Prove Theorem 1: If lim x→⬁ f(x) � L and {an} is a sequence, defined by an � f(n), where n is a positive integer, then, lim n→⬁ an � L., 76. Prove Theorem 4: If lim n→⬁ 冟 an 冟 � 0, then lim n→⬁ an � 0., 77. Prove the properties of the sequence {r n} given on, page 741 using the results lim x→⬁ a x � 0 if 0 � a � 1, and lim x→⬁ a x � ⬁ if a � 1., , 80. If {an} is divergent, then {冟 an 冟} is divergent., 81. If {an} converges to L and {bn} converges to 0, then {anbn}, converges to 0., , 82. If {an} converges and {bn} converges, then {an>bn} converges., 83. If {an} is bounded and {bn} converges, then {anbn} converges., 84. If {an} is bounded, then {an>n} converges to 0., , 85. If lim n→⬁ anbn exists, then both lim n→⬁ an and lim n→⬁ bn, exist., 86. If lim n→⬁ 冟 an 冟 exists, then lim n→⬁ an exists.

Page 17 :

746, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , 9.2, , Series, Consider again the example involving the bouncing ball. Earlier we found a sequence, describing the maximum height attained by the ball on each rebound after hitting a surface. The question that follows naturally is: How do we find the total distance traveled, by the ball? To answer this question, recall that the initial height and the heights attained, on each subsequent rebound are, 1,, , 2 2, a b ,, 3, , 2, ,, 3, , 2 3, a b , p, 3, , meters, respectively. (See Figure 1.) Observe that the distance traveled by the ball when, it first hits the surface is 1 m. When it hits the surface the second time, it will have, traveled a total distance of, 2, 1 � 2a b, 3, , 1�, , or, , 4, 3, , meters. When it hits the surface the third time, it will have traveled a distance of, 2, 2 2, 1 � 2a b � 2a b, 3, 3, , or, , 1�, , 4, 8, �, 3, 9, , meters. Continuing in this fashion, we see that the total distance traveled by the ball is, 2, 2 2, 2 3, 1 � 2a b � 2a b � 2a b � p, 3, 3, 3, , (1), , meters. Observe that this last expression involves the sum of infinitely many terms., y (m), 1, 2, 3, 4, 9, 8, 27, , 0, , FIGURE 1, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 5, , n, , In general, an expression of the form, a1 � a2 � a3 � p � an � p, is called an infinite series or, more simply, a series. The numbers a1, a2, a3, p are, called the terms of the series; an is called the nth term, or general term, of the series;, and the series itself is denoted by the symbol, ⬁, , a an, n�1, , or simply 兺 an.

Page 18 :

9.2, , Series, , 747, , How do we define the “sum” of an infinite series, if it exists? To answer this question, we use the same technique that we have employed several times before: using, quantities that we can compute to help us define new ones. For example, in defining, the slope of the tangent line to the graph of a function, we take the limit of the slope, of secant lines (quantities that we can compute); and in defining the area under the, graph of a function, we take the limit of the sum of the area of rectangles (again, quantities that we can compute). Here, we define the sum of an infinite series as the limit, of a sequence of finite sums (quantities that we can compute)., We can get an inkling of how this may be done from examining the series (1) giving the total distance traveled by the ball. Define the sequence {Sn} by, S1 � 1, 2, S2 � 1 � 2a b, 3, 2, 2 2, S3 � 1 � 2a b � 2a b, 3, 3, o, 2, 2 2, 2 n�1, Sn � 1 � 2a b � 2a b � p � 2a b, 3, 3, 3, giving the total vertical distance traveled by the ball when it hits the surface the first, time, the second time, the third time, p , and the nth time, respectively. If the series, (1) has a sum S (the total distance traveled by the ball), then the terms of the sequence, {Sn} form a sequence of increasingly accurate approximations to S. This suggests that, we define, S � lim Sn, n→⬁, , We will complete the solution to this problem in Example 5., Motivated by this discussion, we define the sum of an infinite series., , DEFINITION Convergence of Infinite Series, Given an infinite series, ⬁, , p, p, a an � a1 � a2 � a3 � � an �, n�1, , the nth partial sum of the series is, n, , Sn � a ak � a1 � a2 � a3 � p � an, k�1, , If the sequence of partial sums {Sn} converges to the number S, that is, if, lim n→⬁ Sn � S, then the series 兺 an converges and has sum S, written, ⬁, , p, p, a an � a1 � a2 � a3 � � an � � S, n�1, , If {Sn} diverges, then the series 兺 an diverges.

Page 19 :

748, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , !, , Be sure to note the difference between a sequence and a series. A sequence is a, succession of terms, whereas a series is a sum of terms., , EXAMPLE 1 Determine whether the series converges. If the series converges, find, its sum., ⬁, , a. a n, n�1, , ⬁, 1, 1, b. a a �, b, n�1, n�1 n, , Solution, a. The nth partial sum of the series is, Sn � 1 � 2 � 3 � p � n �, , n(n � 1), 2, , Since, lim Sn � lim, , n→⬁, , n→⬁, , n(n � 1), �⬁, 2, , ⬁, we conclude that the limit does not exist and 兺n�1, n diverges., b. The nth partial sum of the series is, , 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, Sn � a1 � b � a � b � a � b � p � a, � b�a �, b, n, n, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, n�1, n�1, Removing the parentheses, we see that all the terms of Sn, except for the first and, last, cancel out. So, Sn � 1 �, , 1, n�1, , Since, lim Sn � lim a1 �, , n→⬁, , n→⬁, , 1, b�1, n�1, , we conclude that the series converges and has sum 1, that is,, ⬁, , 1, 1, a an � n � 1b � 1, n�1, The series in Example 1b is called a telescoping series., ⬁, , 4, , EXAMPLE 2 Show that the series a 2, is convergent, and find its sum., n�1 4n � 1, Solution First, we use partial fraction decomposition to rewrite the general term, an � 4>(4n 2 � 1):, an �, , 4, 4n � 1, 2, , �, , 4, 2, 2, �, �, (2n � 1)(2n � 1), 2n � 1, 2n � 1

Page 20 :

9.2, , Series, , 749, , Then we write the nth partial sum of the series as, n, , Sn � a, k�1, , n, 2, 2, �, a a 2k � 1 � 2k � 1 b, 2, 4k � 1, k�1, , 4, , 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, �a � b�a � b�a � b�p�a, �, b, 1, 3, 3, 5, 5, 7, 2n � 1, 2n � 1, �2�, , 2, 2n � 1, , This is a telescoping series., , Since, lim Sn � lim a2 �, , n→⬁, , n→⬁, , 2, b�2, 2n � 1, , we conclude that the given series is convergent and has sum 2; that is,, ⬁, , a, n�1, , 4, 4n � 1, 2, , �2, , Geometric Series, Geometric series play an important role in mathematical analysis. They also arise frequently in the field of finance. The convergence or divergence of a geometric series is, easily established., , DEFINITION Geometric Series, A series of the form, ⬁, , a ar, , n�1, , � a � ar � ar 2 � p � ar n�1 � p, , a, , 0, , n�1, , is called a geometric series with common ratio r., The following theorem tells us the conditions under which a geometric series is, convergent., , THEOREM 1, If 冟 r 冟 � 1, then the geometric series, ⬁, , a ar, , n�1, , � a � ar � ar 2 � p � ar n�1 � p, , n�1, ⬁, a, converges, and its sum is a ar n�1 �, . The series diverges if 冟 r 冟 � 1., 1�r, n�1, , PROOF The nth partial sum of the series is, Sn � a � ar � ar 2 � p � ar n�1, Multiplying both sides of this equation by r gives, rSn � ar � ar 2 � ar 3 � p � ar n

Page 21 :

750, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , Subtracting the second equation from the first then yields, (1 � r)Sn � a � ar n � a(1 � r n), If r, , 1, we can solve the last equation for Sn, obtaining, Sn �, , a(1 � r n), 1�r, , From Example 13 on page 741 we know that lim r n � 0 if 冟 r 冟 � 1, so, n→⬁, , lim Sn � lim, , n→⬁, , n→⬁, , a(1 � r n), a, �, 1�r, 1�r, , This implies that, ⬁, , a ar, , n�1, , n�1, , �, , a, 1�r, , 冟r冟 � 1, , If 冟 r 冟 � 1, then the sequence {r n} diverges, so lim n→⬁ Sn does not exist. This means, that the geometric series diverges. We leave it as an exercise to show that {Sn} diverges, if r � 1, so the series also diverges for these values of r., , EXAMPLE 3 Determine whether the series converges or diverges. If it converges, find, its sum., ⬁, 1 n�1, 3, 3, 3, a. a 3a� b, �3� � � �p, 2, 2, 4, 8, n�1, ⬁, 4 n�1, 20, 80, 320 p, b. a 5a b, �5�, �, �, �, 3, 3, 9, 27, n�1, , Solution, a. This is a geometric series with a � 3 and common ratio r � �12. Since 冟 �12 冟 � 1,, Theorem 1 tells us that the series converges and has sum, ⬁, , 1 n�1, 3, 3a�, b, �, �2, a, 2, 1 � 1 �12 2, n�1, , The graphs of {an} and {Sn} for this series are shown in Figure 2a., b. This is a geometric series with a � 5 and common ratio r � 43. Since 43 � 1,, Theorem 1 tells us that the series is divergent. The graphs of {an} and {Sn} for, this series are shown in Figure 2b., 3, , 2000, , {Sn}, 1000, 0, , {an}, , �1.5, , FIGURE 2, , (a) The geometric series converges, because | r | � 1., , {Sn}, , 20.5, {an}, 0, (b) The geometric series diverges, because | r | � 1., , 20.5

Page 22 :

9.2, , Series, , 751, , EXAMPLE 4 Express the number 3.214 � 3.2141414 p as a rational number., Solution, , We rewrite the number as, 3.2141414 p � 3.2 �, , 14, 3, , 10, , �, , 14, 5, , 10, , �, , 14, 107, , �p, , �, , 32, 14, 1, 1, � 3 c1 � 2 � 4 � p d, 10, 10, 10, 10, , �, , ⬁, 32, 14, 1 n�1, � a a 3b a 2b, 10, 10, n�1 10, , 14, 1, The expression after the first term is a geometric series with a � 1000, and r � 100, . Using, Theorem 1, we have, 14, , 3.2141414 p �, �, , 32, 1000, �, 1, 10, 1 � 100, 32, 14, 3182, �, �, 10, 990, 990, , EXAMPLE 5 Complete the solution of the bouncing ball problem that was introduced, at the beginning of this section. Recall that the total vertical distance traveled by the, ball is given by, 2, 2 2, 2 3, 1 � 2a b � 2a b � 2a b � p, 3, 3, 3, meters., Solution, , If we let d denote the total vertical distance traveled by the ball, then, ⬁, 4 2 n�1, d � 1 � a a ba b, 3, n�1 3, , The expression after the first term is a geometric series with a � 43 and r � 23. Using, Theorem 1, we obtain, d�1�, , 4, 3, , 1 � 23, , �1�4�5, , and conclude that the total distance traveled by the ball is 5 m., , The Harmonic Series, The series, ⬁, 1, 1, 1 p, 1, a n�1�2�3�4�, n�1, , is called the harmonic series. Before showing that this series is divergent, we make, this observation: If a sequence {bn} is convergent, then any subsequence obtained by, deleting any number of terms from the parent sequence {bn} must also converge to the, same limit. Therefore, to show that a sequence is divergent, it suffices to produce a, subsequence of the parent sequence that is divergent.

Page 23 :

752, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , In keeping with this strategy, let us show that the subsequence, S2, S4, S8, S16, p , S2n, p, of the sequence {Sn} of partial sums of the harmonic series is divergent. We have, S2 � 1 �, , 1, 2, , S4 � 1 �, , 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, � a � b � 1 � � a � b � 1 � 2a b, 2, 3, 4, 2, 4, 4, 2, , S8 � 1 �, , 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, �a � b�a � � � b, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, , �1�, S16 � 1 �, �1�, , 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, �a � b�a �p� b�a �p� b, 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 16, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, �a � b�a �p� b�a �p� b, 2, 4, 4, 8, 8, 16, 16, ⎫, ⎪, ⎪, ⎬, ⎪, ⎪, ⎭, , ⎫, ⎪, ⎪, ⎪, ⎬, ⎪, ⎪, ⎪, ⎭, , �1�, , 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, � a � b � a � � � b � 1 � � � � 1 � 3a b, 2, 4, 4, 8, 8, 8, 8, 2, 2, 2, 2, , 4 terms, , 8 terms, , 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, � � � � 1 � 4a b, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, , and, in general, S2n � 1 � n 1 12 2 . Therefore,, , lim S2n � ⬁, , n→⬁, , so {Sn} is divergent. This proves that the harmonic series is divergent., , The Divergence Test, The next theorem tells us that the terms of a convergent series must ultimately approach, zero., , THEOREM 2, ⬁, If 兺n�1, an converges, then lim n→⬁ an � 0., , PROOF We have Sn � a1 � a2 � p � an�1 � an � Sn�1 � an, so an � Sn � Sn�1., ⬁, Since 兺n�1, an is convergent, the sequence {Sn} is convergent. Let lim n→⬁ Sn � S. Then, , lim an � lim (Sn � Sn�1) � lim Sn � lim Sn�1 � S � S � 0, , n→⬁, , n→⬁, , n→⬁, , n→⬁, , The Divergence Test is an important consequence of Theorem 2., , THEOREM 3 The Divergence Test, If lim n→⬁ an does not exist or lim n→⬁ an, , ⬁, 0, then 兺n�1, an diverges.

Page 24 :

9.2, , 753, , Series, , ⬁, The Divergence Test does not say that if lim n→⬁ an � 0, then 兺n�1, an must converge. In other words, the converse of Theorem 2 is not true in general. For example,, ⬁, lim n→⬁ 1>n � 0, yet the harmonic series 兺n�1, 1>n is divergent. In short, the Divergence Test rules out convergence for a series whose nth term does not approach zero, but yields no information if an does approach zero—that is, the series might or might, not converge., , EXAMPLE 6 Show that the following series are divergent., ⬁, , ⬁, , a. a (�1)n�1, , b. a, , n�1, , n�1, , 2n 2 � 1, 3n 2 � 1, , Solution, a. Here, an � (�1)n�1, and, lim an � lim (�1)n�1, , n→⬁, , n→⬁, , does not exist. We conclude by the Divergence Test that the series diverges., 2n 2 � 1, b. Here, an � 2, , and, 3n � 1, , lim an � lim, , n→⬁, , n→⬁, , 2n 2 � 1, 3n � 1, 2, , 2�, � lim, , n→⬁, , 3�, , 1, 2, n2, �, 1, 3, , 0, , n2, , so by the Divergence Test, the series diverges., , Properties of Convergent Series, The following properties of series are immediate consequences of the corresponding, properties of the limits of sequences. We omit the proofs., , THEOREM 4 Properties of Convergent Series, ⬁, ⬁, If 兺n�1, an � A and 兺n�1, bn � B are convergent and c is any real number, then, ⬁, ⬁, 兺n�1 can and 兺n�1(an bn) are also convergent, and, ⬁, , ⬁, , a. a can � c a an � cA, n�1, , ⬁, , ⬁, , b. a (an, , n�1, , n�1, , ⬁, , bn) � a an, n�1, , ⬁, , a bn � A, , B, , n�1, , EXAMPLE 7 Show that the series a c, � n d is convergent, and find its, 3, n�1 n(n � 1), sum., 2, , 4, , ⬁, Solution First, consider the series 兺n�1, 1>[n(n � 1)]. Using partial fraction decomposition, we can write this series in the form, ⬁, , ⬁, 1, 1, 1, �, a n(n � 1), a an � n � 1b, n�1, n�1

Page 25 :

754, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , Using the result of Example 1, we see that, ⬁, , 1, a n(n � 1) � 1, n�1, ⬁, 4, Next, observe that a n is a geometric series with a � 43 and r � 13, so, n�1 3, ⬁, , 4, , 4, 3, �2, a 3n �, 1 � 13, n�1, Therefore, by Theorem 4 the given series is convergent, and, ⬁, ⬁, ⬁, 2, 4, 1, 4, a c n(n � 1) � 3n d � 2 a n(n � 1) � a 3n, n�1, n�1, n�1, , �2ⴢ1�2�0, , 9.2, , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, ⬁, 2. Suppose that 兺n�1, an � 6., a. Evaluate lim n→⬁ Sn, where Sn is the nth partial sum of, ⬁, 兺n�1, an., ⬁, b. Find 兺n�2, an if it is known that a1 � 12., , 1. Explain the difference between, a. A sequence and a series, b. A convergent sequence and a convergent series, c. A divergent sequence and a divergent series, d. The limit of a sequence and the sum of a series, , 9.2, , EXERCISES, , In Exercises 1–6, find the nth partial sum Sn of the telescoping, series, and use it to determine whether the series converges or, diverges. If it converges, find its sum., ⬁, 1, 1, 1. a a, � b, n, n�2 n � 1, , ⬁, 1, 1, 2. a a, �, b, 2n � 1, n�1 2n � 3, , ⬁, 4, 3. a, n�1 (2n � 3)(2n � 5), , ⬁, �8, b, 4. a a 2, n�1 4n � 4n � 3, , ⬁, 1, 1, �, b, 5. a a, ln(n � 1), n�2 ln n, , ⬁, 2, 6. a, n�1 1n � 1 � 1n, , In Exercises 7–14, determine whether the geometric series, converges or diverges. If it converges, find its sum., 7. 4 �, 9., , 8, 16, 32 p, �, �, �, 3, 9, 27, , 5, 5, 5, 5, � �, �, �p, 3, 9, 27, 81, ⬁, , 1 n, b, 11. a 2a�, 12, n�0, ⬁, , 13. a 2n3�n�1, n�0, , 8. �, , 1, 1, 1, 1, � � �, �p, 2, 4, 8, 16, , 10. 1 �, ⬁, , 4, 16, 64 p, �, �, �, 3, 9, 27, en, , 12. a n�1, n�1 3, ⬁, , 14. a (�1)n�13n21�n, , In Exercises 15–22, show that the series diverges., 15., , 1, 2, 3, � � �p, 2, 3, 4, , ⬁, 2n, 17. a, 3n, �1, n�1, ⬁, , 19. a 2(1.5) n, n�1, , 16. 1 �, , 3, 9, 27 p, � �, �, 2, 4, 8, , ⬁, n2, 18. a, 2, n�1 2n � 1, ⬁, (�1)n3n, 20. a, 2n�1, n�0, , ⬁, , 1, 21. a, 2, �, 3�n, n�1, , ⬁, , 22. a, n�1, , n, 22n 2 � 1, , In Exercises 23–28, (a) compute as many terms of the sequence, of partial sums, Sn , as is necessary to convince yourself that, the series converges or diverges. If it converges, estimate its sum., (b) Plot {Sn} to give a visual confirmation of your observation, in part (a). (c). If the series converges, find the exact sum. If it, diverges, prove it, using the Divergence Theorem., ⬁, 6, 23. a, n(n, � 1), n�1, ⬁, , 7, 25. a 3a b, 8, , n�1, , n�1, , n�1, , ⬁, , 27. a sin n 2, n�1, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login., , ⬁, , 24. a, , 2n, , 2n 2 � 1, 2 n�1, 26. a 5a� b, 3, n�1, n�1, ⬁, , ⬁, 1, 1, 28. a a n � n b, 3, n�1 2

Page 26 :

9.2, In Exercises 29–54, determine whether the given series, converges or diverges. If it converges, find its sum., ⬁, 1, 29. a, n(n, � 2), n�1, , ⬁, 1, 30. a 2, n�2 n � 1, , ⬁, 2n, 31. a n, n�0 5, , 32. a, , ⬁, , ⬁, n�0, , (�3)n, , 33. a n�1, n�0 2, , 3n�1, 5n, , ⬁, , n�1, ⬁, , 36. a, n�0, , ⬁, , ⬁, , 37. a 3(1.01)n, , 38. a, , 3n 2 � 2, 3n � 1, , n�1, , 3n�1, , ⬁, , ⬁, , n, , ⬁, , 2, 41. a, n, n�1 1 � (0.2), , 65. Probability of Winning a Dice Toss Peter and Paul take turns tossing a pair of dice. The first person to throw a 7 wins. If, Peter starts the game, then it can be shown that his chances, of winning are, , 2n 2 � n � 1, , n�0, , 1, 1, d, 39. a c n �, n(n � 1), n�1 2, , (�1) 2, 2, d, 40. a c n�1 �, 3n�1, n�1 3, ⬁, , n, b, 42. a lna, n�1, n�1, , ⬁, , 45. a [2(0.1) n � 3(�1)n(0.2)n], n�1, , ⬁, , 3 n, e n�1, 46. a c a� b � a b d, p, 3, n�0, ⬁, , 2n � 5n, b, 48. a a, 3n, n�1, ⬁, , 50. a sin2 n, n�1, , ⬁, , 2n � 3n, b, 47. a a, 6n, n�0, ⬁, , 49. a tan�1 n, n�1, ⬁, 1, 51. a n sin, n, n�1, , ⬁, , sin n, 52. a, 1, � e�n, n�1, , ⬁, n, 53. a, ln, n, n�2, , ⬁, 2 n, 54. a a1 � b, n, n�1, , 55. 0.4 � 0.444 p, , 56. �0.23 � �0.232323 p, , 57. 1.213 � 1.213213213 p, , 58. 3.14234 � 3.142343434 p, , In Exercises 59–62, find the values of x for which the series converges, and find the sum of the series. (Hint: First show that the, series is a geometric series.), 59. a (�x), , ⬁, , n, , 60. a (x � 2), , n�0, , n�0, , ⬁, , ⬁, x 2n, 62. a n, n�0 3, , 61. a 2n (x � 1)n, n�1, , n, , 63. Distance Traveled by a Bouncing Ball A rubber ball is dropped, from a height of 2 m onto a flat surface. Each time the ball, hits the surface, it rebounds to half its previous height. Find, the total distance the ball travels., , 1, 1 5 2, 1 5 4, � a ba b � a ba b � p, 6, 6 6, 6 6, , Find p., 66. Multiplier Effect of a Tax Cut Suppose that the average wage, earner saves 9% of his or her take-home pay and spends the, other 91%. What is the estimated impact that a proposed, $30 billion tax cut will have on the economy over the long, run because of the additional spending generated by the proposed tax cut?, Note: This phenomenon in economics is known as the multiplier, effect., , 67. Perpetuities An annuity is a sequence of payments that are, made at regular time intervals. If the payments are allowed, to continue indefinitely, then it is a perpetuity., a. Suppose that P dollars is paid into an account at the, beginning of each month and that the account earns, interest at the rate of r per year compounded monthly., Then the present value V of the perpetuity (that is, the, value of the perpetuity in today’s dollars) is, V � Pa1 �, , In Exercises 55–58, express each number as a rational number., , ⬁, , p�, , n�1 n, , ⬁, 1, 1, bd, 43. a ccosa b � cosa, n, n�1, n�1, ⬁, n!, 44. a n, n�1 2, , 755, , 64. Finding the Coefficient of Restitution The coefficient of restitution for steel onto steel is measured by dropping a steel ball, onto a steel plate. If the ball is dropped from a height H and, rebounds to a height h, then the coefficient of restitution is, 1h>H. Suppose that a steel ball is dropped from a height of, 1 m onto a steel plate. Each time the ball hits the plate, it, rebounds to r times it previous height (0 � r � 1). If the, ball travels a total distance of 2 m, find the coefficient of, restitution for steel on steel., , 34. a 2�n5n�1, , ⬁, , 2n � 1, 35. a, n�1 3n � 1, , Series, , r �2, r �n, r �1, b � Pa1 � b � p � Pa1 � b � p, 12, 12, 12, , Show that V � 12P>r., b. Mrs. Thompson wishes to establish a fund to provide a, university medical center with a monthly research grant, of $150,000. If the fund will earn interest at the rate of, 9% per year compounded monthly, use the result of part, (a) to find the amount of the endowment she is required, to make now., 68. Residual Concentration of a Drug in the Bloodstream Suppose that, a dose of C units of a certain drug is administered to a, patient and that the fraction of the dose remaining in the, patient’s bloodstream t hr after the dose is administered is, given by Ce�kt, where k is a positive constant., a. Show that the residual concentration of the drug in the, bloodstream after extended treatment when a dose of C, units is administered at intervals of t hr is given by, R�, , Ce�kt, 1 � e�kt

Page 27 :

756, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, b. If the highest concentration of this particular drug that is, considered safe is S units, find the minimal time that, must exist between doses., Hint: C � R, , S, , 69. Capital Value of a Perpetuity The capital value of a perpetuity, involving payments of P dollars paid at the end of each, investment period into a fund that earns interest at the rate, of r per year compounded continuously is given by, A � Pe�r � Pe�2r � Pe�3r � p, Find an expression for A that does not involve an infinite, series., 70. Sum of Areas of Nested Squares An infinite sequence of nested, squares is constructed as follows: Starting with a square, with a side of length 2, each square in the sequence is constructed from the preceding square by drawing line segments, connecting the midpoints of the sides of the square. Find the, sum of the areas of all the squares in the sequence., , 72. Prove or disprove: If 兺 an and 兺 bn are both divergent, then, 兺(an � bn) is divergent., 73. Suppose that 兺 an (an, is divergent., , 0) is convergent. Prove that 兺 1>an, , 74. Suppose that 兺 an is convergent and 兺 bn is divergent. Prove, that 兺(an � bn) is divergent., Hint: Prove by contradiction, using Theorem 4., , 75. Suppose that 兺 an is divergent and c, is divergent., , 0. Prove that 兺 can, , Hint: Prove by contradiction, using Theorem 4., , 76. Prove that if the sequence {an} converges, then the series, 兺(an�1 � an) converges. Conversely, prove that if, 兺(an�1 � an) converges, then {an} converges., ⬁, 3, 1, 77. Show that a 2 converges and, 2, n�1 n, , ⬁, 1, a n2, n�1, , 2., , Hint: See Exercise 71 in Section 9.1., ⬁, 1, 78. Prove that a n, converges by showing that {Sn} is, 2, �1, n�1, increasing and bounded above, where Sn is the nth partial, sum of the series., , In Exercises 79–84, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why it is true. If it is false, explain why, or give an example to show why it is false., ⬁, 79. If lim n→⬁ an � 0, then 兺n�1, an converges., , 71. Sum of Areas of Nested Triangles and Circles An infinite sequence, of nested equilateral triangles and circles is constructed as, follows: Beginning with an equilateral triangle with a side of, length 1, inscribe a circle followed by a triangle, followed, by a circle, and so on, ad infinitum. Find the total area of, the shaded regions., , 80. If lim n→⬁ an � L, then the telescoping series, ⬁, 兺n�1, (an�1 � an) converges and has sum L � a1., ⬁, 81. 兺n�1, sinn x converges for all x in [0, 2p]., ⬁, ar p, 82. a ar n �, provided that 冟 r 冟 � 1., 1�r, n�p, , 83. If the sequence of partial sums of a series 兺 an is bounded, above, then 兺 an must converge., 84. If 兺(an � bn) converges, then both 兺 an and 兺 bn must, converge., , 9.3, , The Integral Test, The convergence or divergence of a telescoping or geometric series is relatively easy to, determine because we are able to find a simple formula involving a finite number of, terms for the nth partial sum Sn of these series. As we saw in Section 9.2, we can find, the actual sum of a convergent series in this case by simply evaluating lim n→⬁ Sn. However, it is often very difficult or impossible to obtain a simple formula for the nth partial sum of an infinite series, and we are forced to look for alternative ways to investigate the convergence or divergence of the series.

Page 28 :

9.3, , The Integral Test, , 757, , In this and the next two sections we will develop several tests for determining the, convergence or divergence of an infinite series by examining the nth term an of the, series. These tests will confirm the convergence of a series without yielding a value for, its sum. From the practical point of view, however, this is all that is required. Once it, has been ascertained that a series is convergent, we can approximate its sum to any, degree of accuracy desired by adding up the terms of its nth partial sum Sn, provided, that n is chosen large enough. The convergence tests that are given here and in Section 9.4 apply only to series with positive terms., , The Integral Test, ⬁, The Integral Test ties the convergence or divergence of an infinite series 兺n�1, an to the, ⬁, convergence or divergence of the improper integral 兰1 f(x) dx, where f(n) � an., , THEOREM 1 The Integral Test, Suppose that f is a continuous, positive, and decreasing function on [1, ⬁). If, f(n) � an for n � 1, then, ⬁, , a an, , and, , n�1, , 冮, , ⬁, , f(x) dx, , 1, , either both converge or both diverge., , PROOF If you examine Figure 1a, you will see that the height of the first rectangle is, a2 � f(2). Since this rectangle has width 1, the area of the rectangle is also a2 � f(2)., Similarly, the area of the second rectangle is a3, and so on. Comparing the sum of the, areas of the first (n � 1) inscribed rectangles with the area of the region under the, graph of f over the interval [1, n], we see that, n, , 冮 f(x) dx, , a2 � a3 � p � an, , 1, , which implies that, n, , Sn � a1 � a2 � a3 � p � an, , a1 �, , 冮 f(x) dx, , (1), , 1, , y, , y, , y � f (x), , y � f (x), , (1, a1), (2, a2), , (2, a2), (3, a3), (n � 1, an�1), , (n, an), a3, , a2, 0, , FIGURE 1, , 1, , 2, , (a) a2 � a3 �, , a4, 3, , a5, 4, , a1, , an, 5, n, , n�1 n, , � an ⱕ y f (x) dx, 1, , x, , 0, , 1, n, , a2, 2, , a3, 3, , a4, 4, , an�1, 5, , (b) y f (x) dx ⱕ a1 � a2 �, 1, , n�1 n, � an�1, , x

Page 29 :

758, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , If 兰1⬁ f(x) dx is convergent and has value L, then, n, , 冮 f(x) dx, , a1 �, , Sn, , a1 � L, , 1, , This shows that {Sn} is bounded above. Also,, Sn�1 � Sn � an�1 � Sn, , Because an�1 � f(n � 1) � 0, , shows that {Sn} is increasing as well. Therefore, by Theorem 6, Section 9.1, {Sn} is, ⬁, convergent. In other words, 兺n�1, an is convergent., Next, by examining Figure 1b, we can see that, n, , 冮 f(x) dx, , a1 � a2 � p � an�1 � Sn�1, , (2), , 1, , So if 兰1⬁ f(x) dx diverges (to infinity because f(x) � 0), then lim n→⬁ Sn�1 �, ⬁, lim n→⬁ Sn � ⬁ , and 兺n�1, an is divergent., Notes, 1. The Integral Test simply tells us whether a series converges or diverges. If it indicates that a series converges, we may not conclude that the (finite) value of the, improper integral used in conjunction with the test is the sum of the convergent, series (see Exercise 54)., 2. Since the convergence of an infinite series is not affected by adding or subtracting, ⬁, a finite number of terms to the series, we sometimes study the series 兺n�N, an �, ⬁, p, aN � aN�1 � rather than the series 兺n�1 an. In this case the series is compared, with the improper integral 兰N⬁ f(x) dx, as we will see in Example 2., ⬁, , 1, , EXAMPLE 1 Use the Integral Test to determine whether a 2, converges or, n�1 n � 1, diverges., Solution Here, an � f(n) � 1>(n 2 � 1), so we consider the function f(x) �, 1>(x 2 � 1). Since f is continuous, positive, and decreasing on [1, ⬁), we may use the, Integral Test. Next,, , 冮, , 1, , ⬁, , 1, x �1, 2, , dx � lim, , 冮, , b→⬁ 1, , b, , 1, x �1, 2, , dx � lim Ctan�1 xD 1, b, , b→⬁, , � lim (tan�1 b � tan�1 1) �, b→⬁, , p, p, p, � �, 2, 4, 4, , ⬁, Since 兰 1>(x � 1) dx converges, we conclude that 兺n�1, 1>(n 2 � 1) converges as, well., ⬁, 1, , 2, , ⬁, , ln n, , EXAMPLE 2 Use the Integral Test to determine whether a, converges or, n�1 n, diverges., Solution Here, an � (ln n)>n, so we consider the function f(x) � (ln x)>x. Observe, that f is continuous and positive on [1, ⬁). Next, we compute, , f ¿(x) �, , 1, xa b � ln x, x, x, , 2, , �, , 1 � ln x, x2

Page 30 :

9.3, , The Integral Test, , 759, , Note that f ¿(x) � 0 if ln x � 1, that is, if x � e. This shows that f is decreasing on, [3, ⬁). Therefore, we may use the Integral Test:, , 冮, , 3, , ⬁, , ln x, dx � lim, x, b→⬁, � lim, , b→⬁, , 冮, , b, , 3, , b, ln x, 1, dx � lim c (ln x)2 d, x, b→⬁ 2, 3, , 1, [(ln b) 2 � (ln 3)2] � ⬁, 2, , ⬁, and we conclude that 兺n�1, (ln n)>n diverges., , The p-Series, The following series will play an important role in our work later on., , DEFINITION p-Series, A p-series is a series of the form, ⬁, , 1, 1, 1, p, a n p � 1 � 2p � 3p �, n�1, where p is a constant., ⬁, Observe that if p � 1, the p-series is just the harmonic series 兺n�1, 1>n., The conditions for the convergence or divergence of the p-series can be found by, applying the Integral Test to the series., , THEOREM 2 Convergence of the p-Series, ⬁, 1, The p-series a p converges if p � 1 and diverges if p, n, n�1, , 1., , PROOF If p � 0, then lim n→⬁ (1>n p) � ⬁ . If p � 0, then lim n→⬁ (1>n p) � 1. In either, , case, lim n→⬁ (1>n p) 0, so the p-series diverges by the Divergence Test., If p � 0, then the function f(x) � 1>x p is continuous, positive, and decreasing on, [1, ⬁). In Example 2 in Section 7.6 we found that 兰1⬁ 1>x p dx converges if p � 1 and, ⬁, diverges if p 1. Using this result and the Integral Test, we conclude that 兺n�1, 1>n p, ⬁, p, converges if p � 1 and diverges if 0 � p 1. Therefore, 兺n�1 1>n converges if p � 1, and diverges if p 1., , EXAMPLE 3 Determine whether the given series converges or diverges., ⬁, , a. a, n�1, , 1, n2, , ⬁, 1, b. a, n�1 1n, , ⬁, , c. a n �1.001, n�1, , Solution, a. This is a p-series with p � 2 � 1, and hence it converges by Theorem 2., ⬁, b. Rewriting the series in the form 兺n�1, 1>n 1>2, we see that the series is a p-series, 1, with p � 2 � 1, and hence it diverges by Theorem 2., ⬁, c. We rewrite the series in the form 兺n�1, 1>n 1.001, which we recognize to be a, p-series with p � 1.001 � 1 and conclude that the series converges.

Page 31 :

760, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , 9.3, , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, , ⬁, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1. Consider the series a 2 � 2 � 2 � 2 � 2 � 2 � p ., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, n�1 n, 1, Let f(x) � 2 ., x, a. Sketch a figure similar to Figure 1a for this series and, function, and compute a1 � f(1) , a2 � f(2), a3 � f(3),, p , an � f(n)., 1, 1, 1, 1, b. Explain why Sn � 2 � 2 � 2 � p � 2, 1, 2, 3, n, n, ⬁, 1, 1, 1, �, dx � 1 �, dx., 2, 2, 12, 1 x, 1 x, c. By evaluating the improper integral in part (b), show that, Sn 2 for each n � 1, 2, 3, p . Then use the Monotone, ⬁, 1, Convergence Theorem (Section 9.1) to show that a 2, n�1 n, converges., , 冮, , ⬁, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2. Consider the series a � � � � � � p ., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, n�1 n, 1, Let f(x) � ., x, a. Sketch a figure similar to Figure 1b for this series and, function, and compute a1 � f(1) , a2 � f(2) , a3 � f(3) ,, p , an � f(n) ., n, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, b. Explain why Sn�1 � � � � p �, dx., �, 1, 2, 3, n�1, 1 x, ⬁, ⬁, 1, 1, c. Show that, dx is divergent, and conclude that a, x, n�1 n, 1, diverges., , 冮, , 冮, , 冮, , Note: This is the harmonic series that was shown to be divergent in, Section 9.2., , Note: The Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler showed that the sum, of this series is p2>6., , 9.3, , EXERCISES, , In Exercises 1–8, use the Integral Test to determine whether the, series is convergent or divergent., ⬁, , ⬁, , 1, , 3, 2. a, n�1 2n � 1, , 1. a 4, n�1 n, ⬁, , 21. a, , n�1, , n�2, ⬁, , 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, �, �, �p, 5. � �, 2, 5, 10, 17, 26, , n�1, , (n � 1), , ⬁, ⬁, , n, 2, , 3>2, , 1, 8. a, n�2 n 1ln n, , In Exercises 9–14, determine whether the p-series is convergent, or divergent., ⬁, 1, 9. a 3, n�1 n, , ⬁, , 10. a, , 1, , ⬁, 1, 11. a 1.01, n�1 n, , n 2>3, ⬁, 1, 12. a e, n, n�1, , ⬁, , ⬁, , 13. a n �p, n�1, , n�1, , 14. a n �0.98, n�1, , In Exercises 15–32 determine whether the given series is, convergent or divergent., ⬁, , 1, 15. a, n�0 1n � 1, , ln n, n, 1, , 23. a, 2, n�2 n(ln n), , 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, � �, �, �, �p, 3, 7, 11, 15, 19, , 7. a, , 1, 2, � 2b, 19. a a, n, n�1 n1n, ⬁, , 4. a ne�n, , n�1, , ⬁, , ⬁, , ⬁, , 3. a e�n, , 6., , ⬁, 1, 17. a, n�1 n1n, , ⬁, , 16. a, n�1, , n, 22n 2 � 1, , 25. a, n�1, ⬁, , 1, sina b, n, n2, 1, , ⬁, , 18. a n �0.75, n�1, ⬁, 2 n, 1, 20. a c a b � 3>2 d, 3, n�1, n, ⬁, ln n, 22. a 2, n, n�2, , ⬁, e1>n, 24. a 2, n�1 n, , ⬁, 1, 26. a, 1n, �4, n�1, , 27. a, 2, n�1 4n � 1, , ⬁, n, 28. a n, 2, n�1, , ⬁, tan�1 n, 29. a 2, n�1 n � 1, , ⬁, 1, 30. a �n, e, �1, n�1, , ⬁, 1, 31. a 2, n�1 n � 2n � 5, , ⬁, 1, 32. a, 2, n�1 2n � 7n � 3, , In Exercises 33 and 34, find the values of p for which the series, is convergent., ⬁, 1, 33. a, p, n�2 n(ln n), , ⬁, ln n, 34. a p, n�1 n, , 35. Find the value(s) of a for which the series, ⬁, 1, a, a c n � 1 � n � 2 d converges. Justify your answer., n�1, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login.

Page 32 :

9.3, 36. a. Show that if Sn is the nth partial sum of the harmonic, series, then Sn 1 � ln n., Hint: Use Inequality (1), page 757, with f(x) � 1>x., , b. Use part (a) to show that the sum of the first 1,000,000, terms of the harmonic series is less than 15. The harmonic series diverges very slowly!, , 1�, , Sn �, , 3, 2, , and therefore,, 0 � ln(n � 1) � ln n, , Hence, deduce that the sequence {an} defined by, an � 1 �, , 1 p 1, � � � ln n, n, 2, , is bounded below., Hint: Use Inequality (2), page 758, with f(x) � 1>x., , b. Show that, , 冮, , 1, �, n�1, , n, , n�1, , 1, dx � ln(n � 1) � ln n, x, , Hint: Draw a figure similar to Figure 1., , ⬁, 1, 43. a 2, ;, n, �1, n�1, , 1, 1, g � lim an � lim a1 � � p � � ln nb, n→⬁, n→⬁, 2, n, whose value is 0.5772 p , is called Euler’s constant., , 38. Riemann Zeta Function The Riemann zeta function for real, numbers is defined by, ⬁, , j(x) � a n �x, , 1, n, , ⬁, , 1, a n2, n�1, , 2, , In Exercises 41–44, use the result of Exercise 39 to find the maximum error if the sum of the series is approximated by Sn., ⬁, 2, 41. a 2 ;, n�1 n, , Note: The number, , Sn �, , Confirm this result, using the result of part (a)., c. Use the result of Exercise 39a to find the upper and, lower bounds on the error incurred in approximating, ⬁, 1, a n 2 using the 100th partial sum of the series., n�1, ⬁, 1, p2, cas d. It can be shown that a, . Use a calculator or, �, 2, 6, n�1 n, computer to verify this., , and use this result to show that the sequence {an}, defined in part (a) is decreasing., c. Use the Monotone Convergence Theorem to show that, {an} is convergent., , ⬁, 1, a n2, n�1, , 1, n�1, , n, ⬁, 1, 1, where Sn � a 2 is the nth partial sum of a 2 ., k�1 k, n�1 n, b. In Exercise 77 in Section 9.2 you were asked to show, that, , 1 p 1, � �, n, 2, , 1, 1, 1 � � p � � ln n, n, 2, , 761, , ⬁, 1, 40. Consider the series a 2 , which is a convergent p-series, n�1 n, (p � 2) ., a. Use the result of Exercise 39b to show that, , 37. Euler’s Constant, a. Show that, ln(n � 1), , The Integral Test, , ⬁, , 42. a, , S40, , 1, , ;, , S20, , 44. a ne�n ;, , S3, , n�1, , n 5>2, , ⬁, , S50, , 2, , n�1, , In Exercises 45–48, use the result of Exercise 39 to find the number of terms of the series that is sufficient to obtain an approximation of the sum of the series accurate to two decimal places., ⬁, 1, 45. a 2, n�1 n, , ⬁, 1, 46. a 3, n�1 n, , ⬁, tan�1 n, 47. a, 2, n�1 1 � n, , ⬁, 1, 48. a, 2, n�2 n(ln n), , n�1, , What is the domain of the function?, 39. Let ak � f(k), where f is a continuous, positive, and, ⬁, an, decreasing function on [n, ⬁) , and suppose that 兺n�1, is convergent., a. Show, by sketching appropriate figures, that if, ⬁, Rn � S � Sn, where S � 兺n�1, an and Sn � 兺nk�1 ak, then, , 冮, , ⬁, , f(x) dx, , Rn, , n�1, , 冮, , f(x) dx, , n, , Note: Rn is the error estimate for the Integral Test., , 冮, , ⬁, , n�1, , f(x) dx, , S, , ⬁, 1, 49. a 4, n�1 n, , ⬁, , 50. a, n�1, , 1, n 9>2, , 51. a. Show that, ⬁, , ⬁, , b. Use the result of part (a) to deduce that, Sn �, , In Exercises 49 and 50, use the result of Exercise 39 to find the, sum of the series accurate to three decimal places using the nth, partial sum of the series., , Sn �, , 冮, , n, , ⬁, , f(x) dx, , ⬁, 1, 1, 1, �, a n(n � 1)(n � 2), a c 2n(n � 1) � 2(n � 1)(n � 2) d, n�1, n�1, , b. Use the results of part (a) to evaluate, ⬁, 1, a n(n � 1)(n � 2), n�1

Page 33 :

762, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , ⬁, 1, 52. Evaluate a 3 accurate to four decimal places by estabn�1 n, lishing parts (a) and (b) and using the results of Exercise 51., , b. Show that the given series is a geometric series, and find, its sum., c. Conclude that although the convergence of 兰0⬁ e�x dx, implies convergence of the infinite series, its value does, not give the sum of the infinite series., , ⬁, ⬁, ⬁, 1, 1, 1, a. a 3 � 1 � a, � a 3 2, (n, �, 1)n(n, �, 1), n, n, (n, � 1), n�1, n�2, n�2, ⬁, 1, b. a 3 2, can be approximated with an accuracy of, n�2 n (n � 1), four decimal places by using six terms of the series., , Hint: Show that, 1, , 2, , n 3 (n 2 � 1), , n5, , if n � 2, and use the result of Exercise 39., ⬁, 1, 53. Use the Integral Test to show that a, n(ln, n)[ln(ln, n)]p, n�3, converges if p � 1 and diverges if p 1., ⬁, 兺n�0, , �n, , e ., 54. Consider the series, a. Evaluate 兰0⬁ e�x dx, and deduce from the Integral Test, that the given series is convergent., , 9.4, , In Exercises 55–58, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why it is true. If it is false, explain why, or give an example to show why it is false., 55. Suppose that f is a continuous, positive, and decreasing, ⬁, function on [1, ⬁). If f(n) � an for n � 1 and 兺n�1, an is, ⬁, ⬁, convergent, then 兺n�1 an a1 � 兰1 f(x) dx., 56. Suppose that f is a continuous, positive, and decreasing, function on [1, ⬁). If f(n) � an for n � 1 and, ⬁, 兰N⬁ f(x) dx � ⬁ , where N is a positive integer, then 兺n�1 an, diverges., 57., , 冮, , 1, , ⬁, , dx, �⬁, x(x � 1), , ⬁, 58. If 兺n�1, an is a convergent series with positive terms, then, ⬁, 兺n�1 1an must also converge., , The Comparison Tests, The rationale for the comparison tests is that the convergence or divergence of a given, series 兺 an can be determined by comparing its terms with the corresponding terms of, a test series whose convergence or divergence is known. The series that we will consider in this section have positive terms., , an, b1, , The Comparison Test, , b3, , b2, , b4, b5, , b6, , a1 a2 a3 a4 a5 a6, 0, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 5, , 6, , 7, , n, , FIGURE 1, Each rectangle representing an is contained in the rectangle representing bn., , Suppose that the terms of a series 兺 an are smaller than the corresponding terms of a, series 兺 bn. This situation is illustrated in Figure 1, where the respective terms of each, series are represented by rectangles, each of width 1 and having the appropriate height., If 兺 bn is convergent, the total area of the rectangles representing this series is finite., Since each rectangle representing the series 兺 an is contained in a corresponding rectangle representing the terms of 兺 bn, the total area of the rectangles representing 兺 an, must also be finite; that is, the series 兺 an must be convergent. A similar argument suggests that if all the terms of a series 兺 an are larger than the corresponding terms of a, series 兺 bn that is known to be divergent, then 兺 an must itself be divergent. These, observations lead to the following theorem., , THEOREM 1 The Comparison Test, Suppose that 兺 an and 兺 bn are series with positive terms., a. If 兺 bn is convergent and an bn for all n, then 兺 an is also convergent., b. If 兺 bn is divergent and an � bn for all n, then 兺 an is also divergent.

Page 34 :

9.4, , The Comparison Tests, , 763, , PROOF Let, n, , n, , Sn � a ak, , Tn � a bk, , and, , k�1, , k�1, , be the nth terms of the sequence of partial sums of 兺 an and 兺 bn, respectively. Since, both series have positive terms, {Sn} and {Tn} are increasing., ⬁, a. If 兺n�1, bn is convergent, then there exists a number L such that lim n→⬁ Tn � L and, Tn L for all n. Since an bn for all n, we have Sn Tn, and this implies that, Sn L for all n. We have shown that {Sn} is increasing and bounded above, so by, the Monotone Convergence Theorem for Sequences of Section 9.1, 兺 an converges., ⬁, b. If 兺n�1, bn is divergent, then lim n→⬁ Tn � ⬁ , since {Tn} is increasing. But an � bn, for all n, and this implies that Sn � Tn, which in turn implies that lim n→⬁ Sn � ⬁ ., Therefore, 兺 an diverges., , To use the Comparison Test, we need a catalog of test series whose convergence, or divergence is known. For the moment we can use the geometric series and the pseries as test series., ⬁, , 1, , EXAMPLE 1 Determine whether the series a 2, converges or diverges., n�1 n � 2, Solution, , Let, an �, , 1, n �2, 2, , If n is large, n � 2 behaves like n , so an behaves like, 2, , 2, , bn �, , 1, n2, , This observation suggests that we compare 兺 an with the test series 兺 bn, which is a, convergent p-series with p � 2. Now,, 0�, , 1, n �2, 2, , �, , 1, , n�1, , n2, , and the given series is indeed “smaller” than the test series 兺 1>n 2. Since the test series, converges, we conclude by the Comparison Test that 兺 1>(n 2 � 2) also converges., ⬁, , 1, , EXAMPLE 2 Determine whether the series a, n converges or diverges., n�1 3 � 2, Solution, , Let, an �, , 1, 3 � 2n, , If n is large, 3 � 2n behaves like 2n, so an behaves like bn � 1 12 2 n. This observation sugn, gests that we compare 兺 an with 兺 bn. Now the series 兺 21n � 兺 1 12 2 is a geometric series, 1, with r � 2 � 1, so it is convergent. Since, an �, , 1, 1, � n � bn, 3 � 2n, 2, , n�1, , the Comparison Test tells us that the given series is convergent.

Page 35 :

764, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, , Note Since the convergence or divergence of a series is not affected by the omission, of a finite number of terms of the series, the condition an bn (or an � bn) for all n, can be replaced by the condition that these inequalities hold for all n � N for some, integer N., ⬁, , 1, , EXAMPLE 3 Determine whether the series a, is convergent or divergent., n�2 1n � 1, Solution, , Let, an �, , 1, 1n � 1, , If n is large, 1n � 1 behaves like 1n, so an behaves like, bn �, , 1, 1n, , Now the series, ⬁, , ⬁, ⬁, 1, 1, b, �, �, a n, a 1n, a 1>2, n�2, n�2, n�2 n, , is a p-series with p � 12 � 1, so it is divergent. Since, an �, , 1, 1, �, � bn, 1n � 1, 1n, , for n � 2, , the Comparison Test implies that the given series is divergent., , The Limit Comparison Test, Consider the series, ⬁, 1, a 1n � 1, n�1, , If n is large, 1n � 1 behaves like 1n, so the nth term of the given series, an �, , 1, 1n � 1, , behaves like, bn �, , 1, 1n, , ⬁, ⬁, bn � 兺n�1, 1> 1n is a divergent p-series with p � 12, we expect, Since the series 兺n�1, ⬁, the series 兺n�1 1>( 1n � 1) to be divergent as well. But the inequality, , an �, , 1, 1, �, � bn, 1n � 1, 1n, , n�1, , ⬁, an is “smaller” than a divergent series, and this is of no help if we, tells us that 兺n�1, try to use the Comparison Test!, In situations like this, the Limit Comparison Test might be applicable. The rationale for this test follows: Suppose that 兺 an and 兺 bn are series with positive terms and

Page 36 :

9.4, , The Comparison Tests, , 765, , suppose that lim n→⬁ (an>bn) � L, where L is a positive constant. If n is large, an>bn ⬇ L, or an ⬇ Lbn. It is reasonable to conjecture that the series 兺 an and 兺 bn must both converge or both diverge., , THEOREM 2 The Limit Comparison Test, Suppose that 兺 an and 兺 bn are series with positive terms and, lim, , n→⬁, , an, �L, bn, , where L is a positive number. Then either both series converge or both diverge., , PROOF Since lim n→⬁ (an>bn) � L � 0, there exists an integer N such that n � N, implies that, , `, , an, 1, � L` � L, bn, 2, , an, 1, 3, L�, � L, 2, bn, 2, or, 1, 3, Lbn � an � Lbn, 2, 2, If 兺 bn converges, so does 兺 32 Lbn. Therefore, the right side of the last inequality implies, that 兺 an converges by the Comparison Test. On the other hand, if 兺 bn diverges, so, does 兺 12 Lbn, and the left side of the last inequality implies by the Comparison Test, that 兺 an diverges as well., ⬁, , 1, , EXAMPLE 4 Show that the series a, is divergent., n�1 1n � 1, Solution As we saw earlier, 1>( 1n � 1) behaves like 1> 1n if n is large. This suggests that we use the Limit Comparison Test with an � 1>( 1n � 1) and bn � 1> 1n., Thus,, 1, an, 1n, 1, 1n � 1, lim, � lim, � lim, � lim, �1, n→⬁ bn, n→⬁, 1, n→⬁ 1n � 1, n→⬁, 1, 1�, 1n, 1n, , ⬁, Since 兺n�1, 1> 1n is divergent 1 it is a p-series with p � 12 2 , we conclude that the given, series is divergent as well., , Note, , You can still use the Comparison Test to solve the problem. Simply observe that, 1, 1, 1, �, �, 1n � 1, 1n � 1n, 21n, , for n � 1, , This suggests picking 兺 bn, where bn � 1>(2 1n), for the test series.

Page 37 :

766, , Chapter 9 Infinite Sequences and Series, ⬁, , 2n 2 � n, , EXAMPLE 5 Determine whether the series a, n�1, , Solution, fore,, , 24n 7 � 3, , converges or diverges., , If n is large, 2n 2 � n behaves like 2n 2, and 4n 7 � 3 behaves like 4n 7. There2n 2 � n, , an �, , 24n 7 � 3, , behaves like, 2n 2, 24n, , 7, , �, , 2n 2, 2n, , �, , 7>2, , 1, n 3>2, , � bn, , Now, lim, , n→⬁, , an, 2n 2 � n, n 3>2, � lim, ⴢ, bn n→⬁ (4n 7 � 3)1>2, 1, � lim, , n→⬁, , 2n 7>2 � n 5>2, (4n 7 � 3)1>2, 1, n, , 2�, � lim, , n→⬁, , a4 �, , b, 7, , 3, n, , 1>2, , Divide numerator and, denominator by n 7>2., , �1, , Since 兺 1>n 3>2 converges 1 it is a p-series with p � 32 2 , the given series converges, by, the Limit Comparison Test., ⬁, , EXAMPLE 6 Determine whether the series a, , 1n � ln n, n2 � 1, , n�1, , converges or diverges., , Solution If n is large, 1n � ln n behaves like 1n. You can see this by comparing, the derivatives of f(x) � 1x and t(x) � ln x:, f ¿(x) �, , 1, 21x, , t¿(x) �, , and, , 1, x, , Observe that t¿(x) approaches zero faster than f ¿(x) approaches zero, as x → ⬁ . This, shows that 1x grows faster than ln x. Also, if n is large, n 2 � 1 behaves like n 2. Therefore,, an �, , 1n � ln n, n2 � 1, , behaves like, 1n, n, , 2, , �, , 1, n 3>2, , � bn

Page 38 :

9.4, , The Comparison Tests, , 767, , Next, we compute, lim, , n→⬁, , an, n 1>2 � ln n n 3>2, � lim, ⴢ, bn n→⬁ n 2 � 1, 1, � lim, , n 2 � n 3>2 ln n, n2 � 1, , n→⬁, , 1�, � lim, , n→⬁, , 1�, , ln n, n 1>2, 1, , Divide the numerator and, denominator by n 2., , n2, , In evaluating this limit, we need to compute, , lim, , x→⬁, , ln x, x 1>2, , 1, x, , � lim, , x→⬁ 1 x �1>2, , � lim, , 2, , x→⬁, , 2, �0, 1x, , Use l’Hôpital’s Rule., , (Incidentally, this result supports the observation made earlier that 1x grows faster, than ln x.) Using this result, we find, an, lim, � lim, n→⬁ bn, n→⬁, , 1�, 1�, , ln n, n 1>2, �1, 1, n2, , Since 兺 1>n 3>2 converges 1 it is a p-series with p � 32 2 , the given series converges, by, the Limit Comparison Test., , 9.4, , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, , 1. a. State the Comparison Test and the Limit Comparison, Test., b. When is the Comparison Test used? When is the Limit, Comparison Test used?, 2. Let 兺 an and 兺 bn be series with positive terms., a. If 兺 bn is convergent and an � bn for all n, what can you, say about the convergence or divergence of 兺 an? Give, examples., b. If 兺 bn is divergent and an bn for all n, what can you, say about the convergence or divergence of 兺 an? Give, examples., , 9.4, , In Exercises 3 and 4, let 兺 an , 兺 bn , and 兺 cn be series with positive terms., 3. If 兺 an is convergent and bn � cn an for all n, what can, you say about the convergence or divergence of 兺 bn and, 兺 cn?, 4. If 兺 an is divergent and bn � cn � an for all n, what can you, say about the convergence or divergence of 兺 bn and 兺 cn?, , EXERCISES, , In Exercises 1–12, use the Comparison Test to determine, whether the series is convergent or divergent., ⬁, 1, 1. a, 2, 2n, �1, n�1, , ⬁, 1, 2. a 2, n, �, 2n, n�1, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login., , ⬁, 1, 3. a, n�3 n � 2, ⬁, , 5. a, n�2, , 1, 2n � 1, 2, , ⬁, , 4. a, n�2, ⬁, , 6. a, n�0, , 1, n 2>3 � 1, 1, 2n � 1, 3

Page 39 :