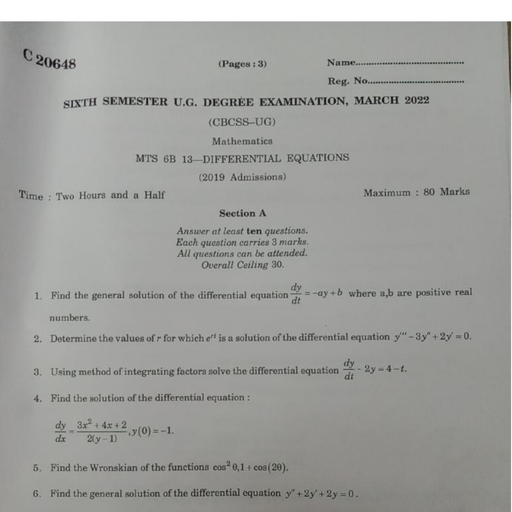

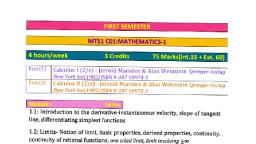

Page 1 :

3, , Marco Simoni/Getty Images, , Antarctic glaciers are calving, into the ocean with greater, frequency as a result of global, warming. A major cause of, global warming is the increase, of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. We can use the derivative to help us study the rate, of change of the average, amount of atmospheric CO2., , Applications of the Derivative, IN THIS CHAPTER we continue to explore the power of the derivative of a function, as a tool for solving problems. We will see how the first and second derivatives of a, function can be used to help us sketch the graph of the function. We will also see, how the derivative of a function can help us find the maximum and minimum values, of the function. Determining these values is important because many practical problems call for finding one or both of these extreme values. For example, an engineer, might be interested in finding the maximum horsepower a prototype engine can, deliver, and a businesswoman might be interested in the level of production of a, certain commodity that will minimize the unit cost of producing that commodity., , V This symbol indicates that one of the following video types is available for enhanced student learning, at www.academic.cengage.com/login:, • Chapter lecture videos, • Solutions to selected exercises, , 243

Page 2 :

244, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, , 3.1, , Extrema of Functions, Absolute Extrema of Functions, The graph of the function f in Figure 1 gives the altitude of a hot-air balloon over the, time interval I � [a, d]. The point (c, f(c)), the lowest point on the graph of f, tells us, that the hot-air balloon attains its minimum altitude, f(c), at time t � c. The smallest, value attained by f for all values of t in the domain I of f, f(c), is called the absolute minimum value of f on I. Similarly, the point (d, f(d)), the highest point on the graph of f,, tells us that the balloon attains its maximum altitude, f(d), at time t � d. The largest value, attained by f for all values of t in I is called the absolute maximum value of f on I., y (ft), , (d, f (d)), , (c, f (c)), , FIGURE 1, The altitude f(t) of a hot-air, balloon for a � t � d, , 0, , a, , b, , c, , d, , t (hr), , More generally, we have the following definitions., , DEFINITIONS Extrema of a Function f, A function f has an absolute maximum at c if f(x) � f(c) for all x in the domain, D of f. The number f(c) is called the maximum value of f on D. Similarly, f, has an absolute minimum at c if f(x) � f(c) for all x in D. The number f(c) is, called the minimum value of f on D. The absolute maximum and absolute minimum values of f on D are called the extreme values, or extrema, of f on D., , EXAMPLE 1 Find the extrema of the function, if any, by examining its graph., a. f(x) � x 2, Solution, y, , b. t(x) � �x 2, , c. h(x) �, , 1, x, , d. k(x) �, , 2x � 7, The graphs of the functions f, t, h, and k are shown in Figure 2., y, , y, , y, , y � x2, 1, y � x_, x, , x, , 0, , y�1, , x, y � _______, √x2 � 7, , 0, 0, , x, , 0, , FIGURE 2, , (b) t has a maximum at 0., , x, y � �1, , y � �x 2, , (a) f has a minimum at 0., , x, 2, , (c) h has no extrema., , (d) k has no extrema.

Page 3 :

3.1, , Extrema of Functions, , 245, , a. f has a minimum value of 0 at 0. Next, since the values of f are not bounded, above, f has no maximum value., b. t has a maximum value of 0 at 0. Also, because the values of t are not bounded, below, t has no minimum value., c. The values of h are neither bounded above nor bounded below, so h has no, absolute extrema., d. As x gets larger and larger, k(x) gets closer and closer to 1. But this value is, never attained; that is, a real number c does not exist such that k(c) � 1. Therefore, k has no maximum value. Similarly, you can show that k has no minimum, value., , EXAMPLE 2 Find the extrema of the function:, a. f(x) � x 2, b. t(x) � x 2, , �1 � x � 2, �1 � x � 2, , Solution, a. The graph of f is shown in Figure 3a. We see that f has a minimum value of 0 at, 0. Next, observe that as x approaches 2 through values less than 2, f(x) increases, and approaches 4. But f never attains the value 4. Therefore, f does not have a, maximum., y, , y, , 4, , 4, y � x2, , y � x2, , 1, , �1, , FIGURE 3, , 1, , 1, , 2, , x, , (a) f has a minimum at 0., , �1, , 1, , 2, , x, , (b) t has a minimum at 0 and a maximum at 2., , b. The graph of t is shown in Figure 3b. As before, we see that t has a minimum, value of 0 at 0. Next, because 2 lies in the domain of t, we see that t does attain, a largest value, namely, t(2) � 4., , Relative Extrema of Functions, If you refer once again to the graph of the function f giving the altitude of a hot-air, balloon over the interval [a, d] shown in Figure 4, you will see that the point (b, f(b)), is the highest point on the graph of f when compared to neighboring points. (For example, it is the highest point when compared to the points (t, f(t)), where a � t � c.) This, tells us that f(b) is the highest altitude attained by the balloon when considered over a, small time interval containing t � b. The value f(b) is called a relative (or local) maximum value of f.

Page 4 :

246, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, y (ft), (b, f (b)), , (c, f (c)), , FIGURE 4, The altitude of a hot-air, balloon for a � t � d, , 0, , a, , b, , c, , d, , t (hr), , Similarly, the point (c, f(c)) is the lowest point on the graph of f when compared, to points nearby. (For example, it is the lowest point when compared to the points, (t, f(t)), where b � t � d.) This tells us that the balloon attains the lowest altitude at, t � c when considered over a small time interval containing t � c. The value f(c) is, called a relative (or local) minimum value of f. Recall that f(c) also happens to be the, (absolute) minimum value of f, as we observed earlier., More generally, we have the following definition., , DEFINITIONS Relative Extrema of a Function, A function f has a relative (or local) maximum at c if f(c) � f(x) for all values of x in some open interval containing c. Similarly, f has a relative (or local), minimum at c if f(c) � f(x) for all values of x in some open interval containing c., , The function f whose graph is shown in Figure 5 has a relative maximum at a and, at c and a relative minimum at b and at d. The graph of f suggests that at a point corresponding to a relative extremum of f, either the tangent line is horizontal or it does, not exist. Put another way, the values of x that correspond to these points are precisely, the numbers in the domain of f at which f ¿ is zero or f ¿ does not exist., y, , FIGURE 5, The function f has relative extrema, at a, b, c, and d. The tangent lines, at a and b are horizontal. There, are no tangent lines at c and d., , 0, , a, , b, , c, , d, , x, , These observations suggest the following theorem, which tells us where the relative extrema of a function may occur., , THEOREM 1 Fermat’s Theorem, If f has a relative extremum at c, then either f ¿(c) � 0 or f ¿(c) does not exist.

Page 5 :

3.1, , Extrema of Functions, , 247, , PROOF First, suppose that f has a relative maximum at c. If f is not differentiable at, c, then there is nothing to prove. So let’s suppose that f ¿(c) exists. Since f has a relative maximum at c, there exists an open interval, I, such that f(x) � f(c) for all x in, I. This implies that if we pick h to be positive and sufficiently small (so that c � h lies, in I), then, f(c � h) � f(c), , or, , f(c � h) � f(c) � 0, , Multiplying both sides of the latter inequality by 1>h, where h � 0, we obtain, f(c � h) � f(c), �0, h, Taking the right-hand limit of both sides of this inequality gives, lim, , h→0�, , f(c � h) � f(c), � lim�0 � 0, h, h→0, , By Theorem 3 of Section 1.2, , Since f ¿(c) exists, we have, f(c � h) � f(c), f(c � h) � f(c), � lim�, h→0, h, h→0, h, , f ¿(c) � lim, , and we have shown that f ¿(c) � 0., Next, we pick h to be negative and sufficiently small (so that c � h lies in I). Then, f(c � h) � f(c), , or, , f(c � h) � f(c) � 0, , Upon multiplying this last inequality by 1>h and reversing the direction of the inequality (because 1>h � 0), we have, f ¿(c) � lim, , h→0, , f(c � h) � f(c), f(c � h) � f(c), � lim�, �0, h, h→0, h, , Thus, we have shown that f ¿(c) � 0 and f ¿(c) � 0, simultaneously. Therefore, f ¿(c) � 0., This proves the theorem for the case in which f has a relative maximum at c. The, case in which f has a relative minimum at c can be proved in a similar manner (see, Exercise 90)., The values of x at which f ¿ is zero or f ¿ does not exist are given a special name., , DEFINITION Critical Number of f, A critical number of a function f is any number c in the domain of f at which, f ¿(c) � 0 or f ¿(c) does not exist., , !, , Theorem 1 states that a relative extremum of f can occur only at a critical number, of f. It is important to realize, however, that the converse of Theorem 1 is false. In, other words, you may not conclude that if c is a critical number of f, then f must, have a relative extremum at c. (See Example 3.), , EXAMPLE 3 Show that zero is a critical number of each of the functions f(x) � x 3, and t(x) � x 1>3 but that neither function has a relative extremum at 0.

Page 6 :

248, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, , Solution The graphs of f and t are shown in Figure 6. Since f ¿(x) � 3x 2 � 0 if x � 0,, we see that 0 is a critical number of f. But observe that f(x) � 0 if x � 0 and f(x) � 0, if x � 0, and this tells us that f cannot have a relative extremum at 0., y, , y, , 1, , 1, y � x3, , 0, , �1, , FIGURE 6, Both f and t have 0 as a critical, number, but neither function, has a relative extremum at 0., , 1, , x, , y � x 1/3, , 0, , �1, , �1, , 1, , x, , �1, (b) The graph of t, , (a) The graph of f, , Next, we compute, t¿(x) �, , 1 �2>3, 1, x, � 2>3, 3, 3x, , Note that t¿ is not defined at 0, but t is; so 0 is a critical number of t. Observe that, t(x) � 0 if x � 0 and t(x) � 0 if x � 0, so t cannot have a relative extremum at 0., , EXAMPLE 4 Find the critical numbers of f(x) � x � 3x 1>3., Solution, , The derivative of f is, f ¿(x) � 1 � x �2>3 �, , x 2>3 � 1, x 2>3, , Observe that f ¿ is not defined at 0 and also f ¿(x) � 0 if x �, cal numbers of f are �1, 0, and 1., , 1. Therefore, the criti-, , We will develop a systematic method for finding the relative extrema of a function, in Section 3.3. For the rest of this section we will develop techniques for finding the, extrema of continuous functions defined on closed intervals., , Finding the Extreme Values of a Continuous, Function on a Closed Interval, As you saw in the preceding examples, an arbitrary function might or might not have, a maximum value or a minimum value. But there is an important case in which the, extrema always exist for a function. The conditions are spelled out in Theorem 2., , THEOREM 2 The Extreme Value Theorem, If f is continuous on a closed interval [a, b], then f attains an absolute maximum, value f(c) for some number c in [a, b] and an absolute minimum value f(d) for, some number d in [a, b].

Page 7 :

3.1, , 249, , Extrema of Functions, , In certain applications, not only is a function continuous on a closed interval, [a, b], but it is also differentiable, with the possible exception of a finite set of numbers, on the open interval (a, b). In such cases, the following procedure can be used to, find the extrema of the function., , Guidelines for Finding the Extrema of a Continuous Function f on [a, b], 1. Find the critical numbers of f that lie in (a, b)., 2. Compute the value of f at each of these critical numbers, and also compute, f(a) and f(b)., 3. The absolute maximum value of f and the absolute minimum value of f are, precisely the largest and the smallest numbers found in Step 2., , This procedure can be justified as follows: If an extremum of f occurs at a number, in the open interval (a, b) , then it must also be a relative extremum of f ; hence it must, occur at a critical number of f. Otherwise, the extremum of f must occur at one or both, of the endpoints of the interval [a, b]. (See Figure 7.), y, , 0, , y, , a, , b, , x, , 0, , (a) The extreme values of f occur at the, endpoints., , y, , a, , b, , x, , (b) The extreme values of f occur at critical, numbers., , 0, , a, , b, , x, , (c) The absolute minimum value of f, occurs at both an endpoint and a critical, number of f , whereas the absolute, maximum value of f occurs at an, endpoint., , FIGURE 7, f is continuous on [a, b]., , EXAMPLE 5 Find the extreme values of the function f(x) � 3x 4 � 4x 3 � 8 on, [�1, 2]., Solution Since f is a polynomial function, it is continuous everywhere; in particular,, it is continuous on the closed interval [�1, 2]. Therefore, we can use the Extreme Value, Theorem., First, we find the critical numbers of f in (�1, 2):, f ¿(x) � 12x 3 � 12x 2, � 12x 2 (x � 1), Observe that f ¿ is continuous on (�1, 2). Next, setting f ¿(x) � 0 gives x � 0 or, x � 1. Therefore, 0 and 1 are the only critical numbers of f in (�1, 2).

Page 8 :

250, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, , Next, we compute f(x) at these critical numbers as well as at the endpoints �1 and, 2. These values are shown in the following table., , y, f (x) � 3x4 � 4x 3 � 8, , (2, 8), , 4, , (�1, �1), , 1, , x, , 2, , x, , �1, , 0, , 1, , 2, , f(x), , �1, , �8, , �9, , 8, , From the table we see that f attains the absolute maximum value of 8 at 2 and the, absolute minimum value of �9 at 1. The graph of f shown in Figure 8 confirms our, results. (You don’t need to draw the graph to solve the problem.), , (0, �8), (1, �9), , FIGURE 8, The maximum value of f is 8, and the, minimum value is �9., , EXAMPLE 6 Find the extreme values of the function f(x) � 2 cos x � x on, [0, 2p]., Solution The function f is continuous everywhere; in particular, it is continuous on, the closed interval [0, 2p]. Therefore, the Extreme Value Theorem is applicable., First, we find the critical numbers of f in (0, 2p). We have, f ¿(x) � �2 sin x � 1, Observe that f ¿ is continuous on (0, 2p). Setting f ¿(x) � 0 gives, �2 sin x � 1 � 0, sin x � �, , 1, 2, , Thus, x � 7p>6 or 11p>6. (Remember x lies in (0, 2p).) So 7p>6 and 11p>6 are the, only critical numbers of f in (0, 2p)., Next, we compute the values of f at these critical numbers as well as at the endpoints 0 and 2p. These values are shown in the following table., 2, 0, , 2π, , x, , 0, , 7p, 6, , 11p, 6, , 2p, , f(x), , 2, , �5.40, , �4.03, , �4.28, , �6, , FIGURE 9, The graph of f(x) � 2 cos x � x, on [0, 2p], , From the table we see that f attains the absolute maximum value of 2 at 0 and the, absolute minimum value of approximately �5.4 at 7p>6. The graph of f shown in Figure 9 confirms our results., , An Optimization Problem, The solution to many practical problems involves finding the absolute maximum or the, absolute minimum of a function. If we know that the function to be optimized is continuous on a closed interval, then the techniques of this section can be used to solve, the problem, as illustrated in the following example.

Page 9 :

3.1, , Extrema of Functions, , 251, , EXAMPLE 7 Maximum Deflection of a Beam Figure 10 depicts a beam of length L, and uniform weight w per unit length that is rigidly fixed at one end and simply supported at the other. An equation of the elastic curve (the dashed curve in the figure) is, y�, , w, (2x 4 � 5Lx 3 � 3L2x 2), 48EI, , where the product EI is a constant called the flexural rigidity of the beam. Show, that the maximum deflection (the displacement of the elastic curve from the x-axis), occurs at x � (15 � 133)L>16 ⬇ 0.578L and has a magnitude of approximately, 0.0054wL4>(EI)., , L, , FIGURE 10, The beam is rigidly fixed at x � 0, and simply supported at x � L., Note the orientation of the y-axis., , x, , 0, y, , Solution We wish to find the value of x on the closed interval [0, L] at which the, function f defined by, w, (2x 4 � 5Lx 3 � 3L2x 2), 48EI, , f(x) �, , attains its absolute maximum value. Since f is continuous on [0, L], this value must be, attained at a critical number of f in (0, L) or at an endpoint of the interval. To find the, critical numbers of f, we compute, f ¿(x) �, , w, (8x 3 � 15Lx 2 � 6L2x), 48EI, , �, , w, x(8x 2 � 15Lx � 6L2), 48EI, , Setting f ¿(x) � 0 gives x � 0 or, x�, , 15L, , �, , 15L, , 2225L2 � 192L2, 16, 133L, 16, , Because (15 � 133)L>16 � L, we see that the sole critical number of f in (0, L), is x � (15 � 133)L>16 ⬇ 0.578L. Evaluating f at 0, 0.578L, and L, we obtain the, following table of values., f(0), 0, , f(0.578L), 0.0054wL, EI, , f(L), , 4, , 0, , We conclude that the maximum deflection occurs at x � (15 � 133)L>16 ⬇ 0.578L, and has a magnitude of approximately 0.0054wL4>(EI).

Page 10 :

252, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, , Our final example shows how a graphing utility can be used to approximate the, maximum and minimum values of a continuous function defined on a closed interval., But to obtain the exact values, we must solve the problem analytically., , EXAMPLE 8 Let f(x) � 2 sin x � sin 2x., a. Use a graphing utility to plot the graph of f using the viewing window, C0, 3p, [�3, 3]. Find the approximate absolute maximum and absolute mini2 D, mum values of f on the interval C0, 3p, 2 D., b. Obtain the exact absolute maximum and absolute minimum values of f analytically., , 3, , 3π, __, 2, , 0, , Solution, a. The required graph is shown in Figure 11. From the graph we see that the, absolute maximum value of f is approximately 2.6 obtained when x ⬇ 1. The, absolute minimum value of f is �2 obtained when x � 3p>2., b. The function f is continuous everywhere and, in particular, on the interval C0, 3p, 2 D., We find, f ¿(x) � 2 cos x � 2 cos 2x, , �3, , FIGURE 11, , � 2 cos x � 2(cos2 x � sin2 x), , cos 2x � cos2 x � sin2 x, , � 2 cos x � 2(cos2 x � 1 � cos2 x), , sin2 x � 1 � cos2 x, , � 2(2 cos2 x � cos x � 1), Since, 2 cos2 x � cos x � 1 � (2 cos x � 1)(cos x � 1) � 0, if cos x � �1 or 12, we see that x � p>3 or p. From the following table we see, that the absolute maximum value of f is 313>2 and the absolute minimum value, of f is �2., , 3.1, , x, , 0, , p, 3, , p, , 3p, 2, , f(x), , 0, , 313, 2, , 0, , �2, , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, , 1. Explain each of the following terms: (a) absolute maximum, value of a function f; (b) relative maximum value of a function f. Illustrate each with an example., 2. a. What is a critical number of a function f?, b. Explain the role of a critical number in determining the, relative extrema of a function., , 3. a. Explain the Extreme Value Theorem in your own words., b. Describe a procedure for finding the extrema of a continuous function f on a closed interval [a, b].

Page 11 :

3.1, , 3.1, , Extrema of Functions, , 253, , EXERCISES, 6. f defined on (�1, ⬁), , In Exercises 1–6, you are given the graph of a function f defined, on the indicated domain. Find the absolute maximum and, absolute minimum values of f (if they exist) and where they are, attained., , y, , 2. f defined on (�⬁, ⬁), , 1. f defined on (0, 2], y, , 1, , y, �1, , 3, , 1, , x, , �1, , 2, 1, 1, �3 �2 �1, �1, , 1 2 3, , 2 x, , 1, , x, , In Exercises 7–24, sketch the graph of the function and find its, absolute maximum and absolute minimum values, if any., 7. f(x) � 2x � 3 on [�1, ⬁), , �2, , 9. h(t) � t � 1 on (�1, 0), 2, , 11. t(x) � x � 1 on (0, ⬁), 2, , 3. f defined on (�⬁, ⬁), , 15. f(x) �, , �4 �3 �2 �1, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 4. f defined on (�2, ⬁), , x, , 3, 2, , 1, , 2, , 3, , x, , 5. f defined on [0, 5], y, , 1, on (0, 1], x, , 16. t(x) �, , 17. f(x) � 冟 x 冟 on [�2, 1), 19. f(t) � 2 sin t on 1 0,, 21., , y, , 2, f(u) � tan u on 1 �p4 , p2 2, 3p, 2, , 20. h(t) � cos pt on C 14, 1 2, , 22. t(u) � sec u on C�p3 , p2 2, , x, if �1 � x � 0, 2 � x if 0 � x � 2, , 24. f(x) � e, , 24 � x 2, �24 � x 2, , if �2 � x � 0, if 0 � x � 2, , In Exercises 25–42, find the critical number(s), if any, of the, function., 25. f(x) � 2x � 3, , 26. t(x) � 4 � 3x, , 27. f(x) � 2x 2 � 4x, , 28. h(t) � 6t 2 � t � 2, , 29. f(x) � x 3 � 6x � 2, , 30. t(t) � 2t 3 � 3t 2 � 12t � 4, , 31. f(x) � 2x 3 � 6x � 7, (1, 37), , 32. f(x) �, , 1 3 1 2, x � x � 2x � 3, 3, 2, , 33. h(x) � x 4 � 4x 3 � 12, , 20, , 34. t(t) � 3t 4 � 4t 3 � 12t 2 � 8, , 10, , 35. f(x) � 3x 4 � 8x 3 � 6x 2 � 24x � 10, 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , x, (5, �5), , 1, on (�1, 1), x, , 18. t(x) � 冟 2x � 1 冟 on (0, 2], , 23. f(x) � e, , 30, , �10, , 12. h(x) � x 2 � 1 on (�2, 1], , 14. t(x) � 2x 2 � 3x � 1 on [0, 1), , 1, , 40, , 10. f(t) � t 2 � 1 on [�1, 0), , 13. f(x) � x 2 � 4x � 3 on (�⬁, ⬁), , y, , �2 �1, �1, �2, , 8. t(x) � �3x � 2 on (�1, 2], , 36. h(z) � z 5 � 5z 3 � 10z � 4, 37. f(x) � x 2>3, 38. t(t) � 4t 1>3 � 3t 4>3, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login.

Page 12 :

254, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, , 39. h(u) �, , u, , 40. t(x) �, , u �1, 2, , 41. f(t) � cos2(2t), , x2, x �3, 2, , 42. t(u) � 2 sin u � cos 2u, , In Exercises 43–60, find the absolute maximum and absolute, minimum values, if any, of the function., 43. f(x) � x 2 � x � 2 on [0, 2], 44. f(x) � �x 2 � 4x � 3 on [�1, 3], , 47. t(x) � 3x 4 � 4x 3 � 1 on [�2, 1], , 50. t(u) �, 51. t(√) �, , Source: Journal of the American Medical Association., , 8 3, x � 8x 2 � 12 on [�2, 3], 3, , x, x �1, 2, , 1u, u2 � 1, , on [�1, 2], on [0, 2], , √, on [2, 4], √�1, , 52. f(x) � 2x �, , 1, on [�1, 3], x, , 53. f(x) � x � 2 1x on [0, 9], 54. f(t) �, , 1 2, t � 4 1t on [0, 9], 8, , 65. Brain Growth and IQs In a study conducted at the National, Institute of Mental Health, researchers followed the development of the cortex, the thinking part of the brain, in, 307 children. Using repeated magnetic resonance imaging, scans from childhood to the late teens, they measured the, thickness (in millimeters) of the cortex of children of age, t years with the highest IQs: 121 to 149. These data lead, to the model, S(t) � 0.000989t 3 � 0.0486t 2 � 0.7116t � 1.46, 5 � t � 19, Show that the cortex of children with superior intelligence, reaches maximum thickness around age 11., , 55. f(x) � x 2>3 (x 2 � 4) on [�1, 2], , Source: Nature., , 56. t(x) � x24 � x 2 on [0, 2], , 66. Brain Growth and IQs Refer to Exercise 65. The researchers at, the institute also measured the thickness (also in millimeters) of the cortex of children of age t years who were of, average intelligence. These data lead to the model, , 57. f(x) � 2 � 3 sin 2x on C0, p2 D, , 58. t(x) � cos x � sin x on [0, 2p], 59. t(t) � 2 sin t � t on C0, p2 D, , A(t) � �0.00005t 3 � 0.000826t 2 � 0.0153t � 4.55, 5 � t � 19, , 60. f(x) � x � sin x on [0, 2p], 61. Maximizing Profit The total daily profit in dollars realized by, the TKK Corporation in the manufacture and sale of x dozen, recordable DVDs is given by the total profit function, P(x) � �0.000001x 3 � 0.001x 2 � 5x � 500, 0 � x � 2000, Find the level of production that will yield a maximum daily, profit., 62. Reaction to a Drug The strength of a human body’s reaction to, a dosage D of a certain drug is given by, k, D, R�D a � b, 2, 3, 2, , where k is a positive constant. Show that the maximum reaction is achieved if the dosage is k units., 63. Traffic Flow The average speed of traffic flow on a stretch of, Route 124 between 6 A.M. and 10 A.M. on a typical weekday, is approximated by the function, f(t) � 20t � 401t � 50, , 0�t�9, , where t is measured in decades with t = 0 corresponding to, the beginning of 1910. Show that the percentage of foreignborn medical residents was lowest in early 1970., , 46. f(t) � �2t 3 � 3t 2 � 12t � 3 on [�2, 3], , 49. f(x) �, , 64. Foreign-Born Medical Residents The percentage of foreign-born, medical residents in the United States from the beginning, of 1910 to the beginning of 2000 is approximated by the, function, P(t) � 0.04363t 3 � 0.267t 2 � 1.59t � 14.7, , 45. h(x) � x 3 � 3x 2 � 1 on [�3, 2], , 48. f(x) � 2x 4 �, , where f(t) is measured in miles per hour and t is measured, in hours, with t � 0 corresponding to 6 A.M. At what time in, the morning is the average speed of traffic flow highest? At, what time in the morning is it lowest?, , 0�t�4, , Show that the cortex of children with average intelligence, reaches maximum thickness at age 6., Source: Nature., , 67. Maximizing Revenue The quantity demanded per month of the, Peget wristwatch is related to the unit price by the demand, equation, p�, , 50, 0.01x 2 � 1, , 0 � x � 20, , where p is measured in dollars and x is measured in units of, a thousand. How many watches must be sold by the manufacturer to maximize its revenue?, Hint: Recall that the revenue R � px., , 68. Poiseuille’s Law According to Poiseuille’s Law, the velocity, (in centimeters per second) of blood r cm from the central, axis of an artery is given by, √(r) � k(R2 � r 2), , 0�r�R

Page 13 :

3.1, where k is a constant and R is the radius of the artery. Show, that the flow of blood is fastest along the central axis. Where, is the flow of blood slowest?, R, , 72. Air Pollution According to the South Coast Air Quality Management district, the level of nitrogen dioxide, a brown gas, that impairs breathing, that is present in the atmosphere, between 7 A.M. and 2 P.M. on a certain May day in downtown Los Angeles is approximated by, I(t) � 0.03t 3(t � 7)4 � 60.2, , 69. Chemical Reaction In an autocatalytic chemical reaction the, product formed acts as a catalyst for the reaction. If Q is the, amount of the original substrate that is present initially and, x is the amount of catalyst formed, then the rate of change, of the chemical reaction with respect to the amount of catalyst present in the reaction is, R(x) � kx(Q � x), , 0�x�Q, , where k is a constant. Show that the rate of the chemical, reaction is greatest at the point at which exactly half of the, original substrate has been transformed., 70. Velocity of Airflow During a Cough When a person coughs, the, trachea (windpipe) contracts, allowing air to be expelled at a, maximum velocity. It can be shown that the velocity √ of, airflow during a cough is given by, √ � f(r) � kr 2(R � r), , 0�r�R, , where r is the radius of the trachea in centimeters during, a cough, R is the normal radius of the trachea in centimeters, and k is a constant that depends on the length of the, trachea. Find the radius for which the velocity of airflow, is greatest., 71. A Mixture Problem A tank initially contains 10 gal of brine, with 2 lb of salt. Brine with 1.5 lb of salt per gallon enters, the tank at the rate of 3 gal/min, and the well-stirred mixture, leaves the tank at the rate of 4 gal/min. It can be shown that, the amount of salt in the tank after t min is x lb, where, x � f(t) � 1.5(10 � t) � 0.0013(10 � t)4, , 255, , Extrema of Functions, , 0�t�7, , where I(t) is measured in pollutant standard index (PSI) and, t is measured in hours, with t � 0 corresponding to 7 A.M., Determine the time of day when the PSI is the lowest and, when it is the highest., Source: The Los Angeles Times., , 73. Office Rents After the economy softened, the sky-high office, space rents of the late 1990s started to come down to earth., The function R gives the approximate price per square foot, in dollars, R(t), of prime space in Boston’s Back Bay and, Financial District from the beginning of 1997 (t � 0) to the, beginning of 2002 (t � 5), where, R(t) � �0.711t 3 � 3.76t 2 � 0.2t � 36.5, , 0�t�5, , Show that the office space rents peaked at about the middle, of the year 2000. What was the highest office space rent, during the period in question?, Source: Meredith & Grew Inc./Oncor., , 74. Maximum Deflection of a Beam A uniform beam of length L ft, and negligible weight rests on supports at both ends. When, subjected to a uniform load of w0 lb/ft, it bends and has the, elastic curve (the dashed curve in the figure below) described, by the equation, y�, , w0, (x 4 � 2Lx 3 � L3x), 24EI, , 0�x�L, , where the product EI is a constant called the flexural rigidity, of the beam. Show that the maximum deflection of the beam, occurs at the midpoint of the beam and that its value is, 5w0L4>(384EI) ., , 0 � t � 10, , What is the maximum amount of salt present in the tank at, any time?, , 0, , L, x (ft), , y (ft), , 75. Use of Diesel Engines Diesel engines are popular in cars in, Europe, where fuel prices are high. The percentage of new, vehicles in Western Europe equipped with diesel engines is, approximated by the function, f(t) � 0.3t 4 � 2.58t 3 � 8.11t 2 � 7.71t � 23.75, 0�t�4, where t is measured in years, with t � 0 corresponding to, the beginning of 1996.

Page 14 :

256, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, a. Plot the graph of f using the viewing window, [0, 4] [0, 40]., b. What was the lowest percentage of new vehicles, equipped with diesel engines for the period in question?, , y (%), 100, , y � P(t), , Source: German Automobile Industry Association., , 76. Federal Debt According to data obtained from the Congressional Budget Office, the national debt (in trillions of dollars) is given by the function, f(t) � 0.0022t 3 � 0.0465t 2 � 0.506t � 3.27, , 75, P, 0, , 0 � t � 20, , where t is measured in years, with t � 0 corresponding to, the beginning of 1990., a. Plot the graph of f using the viewing window, [0, 20] [0, 14]., b. When was the federal debt at the highest level over the, period under consideration? What was that level?, , 79. Path of a Boat A boat leaves the point O (the origin) located, on one bank of a river, traveling with a constant speed of, 20 mph and always heading toward a dock located at the, point A (1000, 0), which is due east of the origin (see the, figure). The river flows north at a constant speed of 5 mph., It can be shown that the path of the boat is, y � 500 c a, , Source: Congressional Budget Office., , 77. A cylindrical tank of height h is filled with water. Suppose a, jet of water flows through an orifice on the tank. According, to Torricelli’s law, the velocity of flow of the jet of water is, given by V � 12tx where t is the gravitational constant. It, can be shown that the range R (in feet) of the jet of water is, given by R � 2 1x(h � x). Where should the orifice be, located so that the jet of water will have the maximum, range?, , t (days), , 1000 � x 3>4, 1000 � x 5>4, b �a, b d, 1000, 1000, 0 � x � 1000, , Find the maximum distance the boat has drifted north during, its trip., y (ft), N, W, , E, S, , x, h, , O, R, , 78. Water Pollution When organic waste is dumped into a pond,, the oxidation process that takes place reduces the pond’s, oxygen content. However, given time, nature will restore, the oxygen content to its natural level. In the accompanying, graph, P(t) gives the oxygen content (as a percentage of its, normal level) t days after organic waste has been dumped, into the pond. Suppose that the oxygen content t days after, the organic waste has been dumped into the pond is given by, P(t) � 100 a, , t 2 � 10t � 100, t 2 � 20t � 100, , b, , percent of its normal level. Find the coordinates of the point, P, and explain its significance., , A (1000, 0), , x (ft), , 80. Construction of an AC Transformer In constructing an AC transformer, a cross-shaped iron core is inserted into a coil (see, the figure). If the radius of the coil is a, find the values of x, and y such that the iron core has the largest surface area., Hint: Let x � a cos u and y � a sin u. Then maximize the function, S � 4xy � 4y(x � y) � 8xy � 4y 2, � 4a 2 (sin 2u � sin2 u), on the interval 0 � u �, , p, 4., , a, q, x, , y

Page 15 :

3.1, 81. A body of mass m moves in an elliptical path with a constant angular speed v (see the figure). It can be shown that, the force acting on the body is always directed toward the, origin and has magnitude given by, F � mv 2a cos vt � b sin vt, 2, , 2, , 2, , 2, , 2, , where the product EI is a constant called the flexural rigidity, of the beam. Find the maximum deflection of the beam., Hint: Maximize y � f(x) over each interval [0, 1] and [1, 3] separately. Then combine your results., , t�0, , where a and b are constants with a � b. Find the points on, the path where the force is greatest and where it is smallest., Does your result agree with your intuition?, , 257, , Extrema of Functions, , W, 3, , 0, 1, , x (ft), , y, y (ft), , b, �a, , 84. Let, a x, , 0, , f(x) � e, , �b, , 82. The object shown in the figure is a crate full of office equipment that weighs W lb. Suppose you try to move the crate, by tying a rope around it and pulling on the rope at an angle, u to the horizontal. Then the magnitude F of the force that, is required to set the crate in motion is, mW, F�, m sin u � cos u, , 0�u�, , Show that f is discontinuous at x � 0 but attains an absolute, maximum value and an absolute minimum value on [�1, 1]., Does this contradict the Extreme Value Theorem?, 85. Let, f(x) � e, , p, 2, , where m is a constant called the coefficient of static friction., a. Find the angle u at which F is minimized., b. What is the magnitude of the force found in part (a)?, c. Suppose W � 60 and m � 0.4. Plot the graph of F as a, function of u on the interval C0, p2 D . Then verify the result, obtained in parts (a) and (b) for this special case., , �x, if �1 � x � 0, x � 1 if 0 � x � 1, , x2 � 1, 2, , if �1 � x � 2, if 2 � x � 4, , Show that f attains an absolute maximum value and an, absolute minimum value on the open interval (�1, 4). Does, this contradict the Extreme Value Theorem?, 86. Show that the function f(x) � x 3 � x � 1 has no relative, extrema on (�⬁, ⬁)., 87. Find the critical numbers of the greatest integer function, f(x) � Œ xœ ., 88. Find the absolute maximum value and the absolute minimum value (if any) of the function t(x) � x � Œ xœ , where, f(x) � Œxœ is the greatest integer function., , 89. Show that the function f(x) � sin(1>x) has infinitely many, critical numbers in any open interval that contains the origin., 90. a. Suppose f has a relative minimum at c. Show that the, function t defined by t(x) � �f(x) has a relative maximum at c., b. Use the result of (a) to prove Theorem 1 for the case in, which f has a relative minimum at c., , q, , 83. A uniform beam of length 3 ft and negligible weight is supported at both ends. When subjected to a concentrated load, W at a distance 1 ft from one end, it bends and has the elastic curve (the dashed curve in the figure) described by the, equation, W, (5x � x 3), 9EI, y�d, W, (x 3 � 9x 2 � 19x � 3), 18EI, , if 0 � x � 1, if 1 � x � 3, , In Exercises 91–94, plot the graph of f and use the graph to estimate the absolute maximum and absolute minimum values of f in, the given interval., 91. f(x) � �0.02x 5 � 0.3x 4 � 2x 3 � 6x � 4 on [�2, 2], 92. f(x) � 0.3x 6 � 2x 4 � 3x 2 � 3 on [0, 2], 93. f(x) �, 94. f(x) �, , 0.2x 2, 3x � 2x 2 � 1, 4, , on [0, 4], , x � cos x, on [0, 2], 1 � 0.5 sin x

Page 16 :

258, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, , In Exercises 95–98, (a) plot the graph of f in the given viewing, window and find the approximate absolute maximum and absolute, minimum values accurate to three decimal places, and (b) obtain, the exact absolute maximum and absolute minimum values of f, analytically., 95. f(x) �, , 1 4 3, x � x � 2 on [�1, 2], 2, 2, , 96. f(x) � x � 21 � x 2 on [�1, 1], 97. f(x) �, , x�1, on [0, 1], 1x � 1, , 98. f(x) � 2 sin x � x on C0, p2 D, , 3.2, , In Exercises 99–102, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why it is true. If it is false, explain why, or give an example to show why it is false., 99. If f ¿(c) � 0, then f has a relative maximum or a relative, minimum at c., 100. If f has a relative minimum at c, then f ¿(c) � 0., , [0, 8], , 101. If f is defined on the closed interval [a, b], then f has an, absolute minimum value in [a, b]., , [�2, 2], , 102. If f is continuous on the interval (a, b), then f attains an, absolute minimum value at some number c in (a, b)., , [0.8, 1], [0, 1], , The Mean Value Theorem, Rolle’s Theorem, The graph of the function f shown in Figure 1 gives the depth of a radical new twinpiloted submarine during a test dive. The submarine is on the surface at t � a [ f(a) � 0], when it commences its dive. It resurfaces at t � b [ f(b) � 0], the end of the test run., As you can see from the graph of f, there is at least one point on the graph of f at which, the tangent line to the curve is horizontal., y (ft), , Historical Biography, MICHEL ROLLE, (1652–1719), It is interesting to note that the theorem, that bears Michel Rolle’s name—which was, originally included in a 1691 book on geometry and algebra—is the basis for so many, concepts in calculus, given that Rolle himself was skeptical of the topic’s validity., Rolle attacked as a set of untruths what, were then the newly developing infinitesimal methods, now known as calculus. Eventually convinced of the validity of calculus, by Pierre Varignon (1654–1722), Rolle later, voiced his support for the subject. Shortly, thereafter, the general opposition to calculus collapsed, followed by many new, advances in the content area. Rolle’s Theorem is now found in the development of, many of the introductory topics of differential calculus., , 0, , a, , b, , t (min), , FIGURE 1, f(t) gives the depth of the submarine at time t., , We can convince ourselves that there must exist at least one such point on the graph, of f through the following intuitive argument: Since we know that the submarine, returned to the surface, there must be at least one point on the graph of f that corresponds to the time when the submarine stops diving and begins to resurface. The tangent line to the graph of f at this point must be horizontal., A mathematical description of this phenomenon is contained in Rolle’s Theorem,, named in honor of the French mathematician Michel Rolle (1652–1719)., , THEOREM 1 Rolle’s Theorem, Let f be continuous on [a, b] and differentiable on (a, b). If f(a) � f(b), then, there exists at least one number c in (a, b) such that f ¿(c) � 0.

Page 17 :

3.2, , 259, , The Mean Value Theorem, , PROOF Let f(a) � f(b) � d. There are two cases to consider (see Figure 2)., y, y, , FIGURE 2, Geometric interpretations, of Rolle’s Theorem, , 0, , y = f(x), , y=d, , d, , a, , c1, , c2, , b, , d, , x, , (a) Case 1, , 0, , a, , c1, , c2, , b, , x, , (b) Case 2, , Case 1 f(x) � d for all x in [a, b] (see Figure 2a)., In this case, f ¿(x) � 0 for all x in (a, b), so f ¿(c) � 0 for any number c in (a, b)., Case 2 f(x) d for at least one x in [a, b] (see Figure 2b)., In this case there must be a number x in (a, b) where f(x) � d or f(x) � d. First, suppose that f(x) � d. Since f is continuous on [a, b], the Extreme Value Theorem implies, that f attains an absolute maximum value at some number c in [a, b]. The number c, cannot be an endpoint because f(a) � f(b) � d, and we have assumed that f(x) � d, for some number x in (a, b). Therefore, c must be in (a, b). Since f is differentiable on, (a, b), f ¿(c) exists, and by Fermat’s Theorem f ¿(c) � 0., The proof for the case in which f(x) � d is similar and is left as an exercise (Exercise 39)., , EXAMPLE 1 Let f(x) � x 3 � x for x in [�1, 1]., a. Show that f satisfies the hypotheses of Rolle’s Theorem on [�1, 1]., b. Find the number(s) c in (�1, 1) such that f ¿(c) � 0 as guaranteed by Rolle’s, Theorem., , y, 1, y � x3 � x, , �1, , 3, � __, 3, , 0, , __3, , 1, , 3, , �1, , FIGURE 3, The numbers c1 � � 13>3 and, c2 � 13>3 satisfy f ¿(c) � 0 as, guaranteed by Rolle’s Theorem., , x, , Solution, a. The polynomial function f is continuous and differentiable on (�⬁, ⬁). In particular, it is continuous on [�1, 1] and differentiable on (�1, 1). Furthermore,, f(�1) � (�1)3 � (�1) � 0, , and, , f(1) � 13 � 1 � 0, , and the hypotheses of Rolle’s theorem are satisfied., b. Rolle’s Theorem guarantees that there exists at least one number c in (�1, 1), such that f ¿(c) � 0. But f ¿(x) � 3x 2 � 1, so to find c, we solve, 3c2 � 1 � 0, obtaining c � 13>3. In other words, there are two numbers, c1 � � 13>3 and, c2 � 13>3, in (�1, 1) for which f ¿(c) � 0 (Figure 3)., , EXAMPLE 2 A Real-Life Illustration of Rolle’s Theorem During a test dive of a prototype of a twin-piloted submarine, the depth in feet of the submarine at time t in minutes is given by h(t) � t 3(t � 7)4, where 0 � t � 7., a. Use Rolle’s Theorem to show that there is some instant of time t � c between 0, and 7 when h¿(c) � 0., b. Find the number c and interpret your results.

Page 18 :

260, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, , Solution, a. The polynomial function h is continuous on [0, 7] and differentiable on (0, 7)., Furthermore, h(0) � 0 and h(7) � 0, so the hypotheses of Rolle’s Theorem, are satisfied. Therefore, there exists at least one number c in (0, 7) such that, h¿(c) � 0., b. To find the value of c, we first compute, h¿(t) � 3t 2(t � 7)4 � t 3 (4)(t � 7)3, , y (ft), 7000, , � t 2(t � 7)3[3(t � 7) � 4t], , (3, 6912), , � 7t 2(t � 7)3(t � 3), , y � t 3(t � 7) 4, , 0, , 3, , 7, , t (min), , FIGURE 4, The submarine is at a depth of h(t) feet, at time t minutes., , Setting h¿(t) � 0 gives t � 0, 3, or 7. Since 3 is the only number in the interval, (0, 7) such that h¿(3) � 0, we see that c � 3. Interpreting our results, we see, that the submarine is on the surface initially (since h(0) � 0) and returns to the, surface again after 7 minutes (since h(7) � 0). The vertical component of the, velocity of the submarine is zero at t � 3, at which time the submarine attains, the greatest depth of h(3) � 33 (3 � 7)4 � 6912 ft. The graph of h is shown in, Figure 4., Rolle’s Theorem is a special case of a more general result known as the Mean Value, Theorem., , THEOREM 2 The Mean Value Theorem, Let f be continuous on [a, b] and differentiable on (a, b). Then there exists at, least one number c in (a, b) such that, f ¿(c) �, , f(b) � f(a), b�a, , (1), , To interpret this theorem geometrically, notice that the quotient in Equation (1) is, just the slope of the secant line passing through the points P(a, f(a)) and Q(b, f(b)), lying on the graph of f (Figure 5). The quantity f ¿(c) on the left, however, gives the, slope of the tangent line to the graph of f at x � c. The Mean Value Theorem tells us, that under suitable conditions on f, there is always at least one point (c, f(c)) on the, graph of f for a � c � b such that the tangent line to the graph of f at this point is, parallel to the secant line passing through P and Q. Observe that if f(a) � f(b), then, Theorem 2 reduces to Rolle’s Theorem., y, T, (c, f (c)), , S, Q(b, f (b)), , P(a, f (a)), , FIGURE 5, The tangent line T at (c, f(c)) is parallel, to the secant line S through P and Q., , 0, , a, , c, , b, , x

Page 19 :

3.2, , The Mean Value Theorem, , 261, , PROOF If you examine Figure 5, you will see that the vertical distance between the, graph of f and the secant line S passing through P and Q is maximal at x � c. This, observation gives a clue to the proof of the Mean Value Theorem: Find a function whose, absolute value gives the vertical distances between the graph of f and the secant line., Then optimize this function., Now an equation of the secant line can be found by using the point-slope form of, the equation of a line with slope [ f(b) � f(a)]>(b � a) and the point (b, f(b)). Thus,, y � f(b) �, , f(b) � f(a), ⴢ (x � b), b�a, , y � f(b) �, , f(b) � f(a), ⴢ (x � b), b�a, , or, , Define the function D by, D(x) � f(x) � cf(b) �, , f(b) � f(a), ⴢ (x � b)d, b�a, , (2), , Notice that 冟 D(x) 冟 gives the vertical distance between the graph of f and the secant line, through P and Q (Figure 6). The function D is continuous on [a, b] and differentiable, on (a, b), so we can use Rolle’s Theorem on D. First, we note that D(a) � D(b) � 0., Therefore, there exists at least one number c in (a, b) such that D¿(c) � 0. But, D¿(x) � f ¿(x) �, , f(b) � f(a), b�a, , so D¿(c) � 0 implies that, 0 � f ¿(c) �, , f(b) � f(a), b�a, , or, f ¿(c) �, , f(b) � f(a), b�a, , as was to be shown., y, , y, y � f (x), P(a, f (a)), , Q(b, f (b)), 冷 D(x)冷, y � f (b) �, , y � f(b) �, f (b) � f (a), b�a, , y � f (x), , (x � b), , 冷 D(x)冷, , f (b) � f(a), b�a, Q(b, f (b)), , P(a, f (a)), , 0, , x, , 0, , x, , FIGURE 6, 冟 D(x) 冟 gives the vertical distance between the graph of f and the secant line passing through P and Q., , (x � b)

Page 20 :

262, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, , EXAMPLE 3 Let f(x) � x 3., a. Show that f satisfies the hypotheses of the Mean Value Theorem on [�1, 1]., b. Find the number(s) c in (�1, 1) that satisfy Equation (1) as guaranteed by the, Mean Value Theorem., y, 1, , (1, f (1)), y � x3, , 3, � __, 3, , �1, , __3, , 1, , Solution, a. f is a polynomial function, so it is continuous and differentiable on (�⬁, ⬁). In, particular, f is continuous on [�1, 1] and differentiable on (�1, 1). So the, hypotheses of the Mean Value Theorem are satisfied., b. f ¿(x) � 3x 2, so f ¿(c) � 3c2. With a � �1 and b � 1, Equation (1) gives, f(1) � f(�1), � f ¿(c), 1 � (�1), , x, , 3, , or, �1, (�1, f(�1)), , FIGURE 7, The numbers c1 � � 13>3 and, c2 � 13>3 satisfy Equation (1),, as guaranteed by the Mean Value, Theorem., , 1 � (�1), � 3c2, 1 � (�1), 1 � 3c2, and c � 13>3. So there are two numbers, c1 � � 13>3 and c2 � 13>3, in, (�1, 1) that satisfy Equation (1). (See Figure 7.), The next example gives an interpretation of the Mean Value Theorem in a real-life, setting., , EXAMPLE 4 The Mean Value Theorem and the Maglev The position of a maglev moving along a straight, elevated monorail track is given by s � f(t) � 4t 2, 0 � t � 30,, where s is measured in feet and t is measured in seconds. Then the average velocity of, the maglev during the first 4 sec of the run is, f(4) � f(0), 64 � 0, �, � 16, 4�0, 4, , (3), , or 16 ft/sec. Next, since f is continuous on [0, 4] and differentiable on (0, 4), the Mean, Value Theorem guarantees that there is a number c in (0, 4) such that, f(4) � f(0), � f ¿(c), 4�0, , (4), , But f ¿(t) � 8t, so using Equation (3), we see that Equation (4) is equivalent to, 16 � 8c, or c � 2. Since f ¿(t) measures the instantaneous velocity of the maglev at any time t,, the Mean Value Theorem tells us that at some time t between t � 0 and t � 4 (in this, case, t � 2) the maglev must attain an instantaneous velocity equal to the average velocity of the maglev over the time interval [0, 4]., , Some Consequences of the Mean Value Theorem, An important application of the Mean Value Theorem is to establish other mathematical results. For example, we know that the derivative of a constant function is zero., Now we can show that the converse is also true.

Page 21 :

3.2, , The Mean Value Theorem, , 263, , THEOREM 3, If f ¿(x) � 0 for all x in an interval (a, b), then f is constant on (a, b)., , PROOF Suppose that f ¿(x) � 0 for all x in (a, b). To prove that f is constant on, (a, b), it suffices to show that f has the same value at every pair of numbers in (a, b)., So let x 1 and x 2 be arbitrary numbers in (a, b) with x 1 � x 2. Since f is differentiable, on (a, b), it is also differentiable on (x 1, x 2) and continuous on [x 1, x 2]. Therefore, the, hypotheses of the Mean Value Theorem are satisfied on the interval [x 1, x 2]. Applying, the theorem, we see that there exists a number c in (x 1, x 2) such that, f ¿(c) �, , f(x 2) � f(x 1), x2 � x1, , (5), , But by hypothesis, f ¿(x) � 0 for all x in (a, b), so f ¿(c) � 0. Therefore, Equation (5), implies that f(x 2) � f(x 1) � 0, or f(x 1) � f(x 2) ; that is, f has the same value at any, two numbers in (a, b). This completes the proof., , COROLLARY TO THEOREM 3, If f ¿(x) � t¿(x) for all x in an interval (a, b), then f and t differ by a constant on, (a, b); that is, there exists a constant c such that f(x) � t(x) � c for all x in, (a, b)., , PROOF Let h(x) � f(x) � t(x). Then, h¿(x) � f ¿(x) � t¿(x) � 0, for every x in (a, b). By Theorem 3, h is constant; that is, f � t is constant on (a, b)., Thus, f(x) � t(x) � c for some constant c and f(x) � t(x) � c for all x in (a, b)., , Determining the Number of Zeros of a Function, Our final example brings together two important theorems—the Intermediate Value, Theorem and Rolle’s Theorem—to help us determine the number of zeros of a function f in a given interval [a, b]., , EXAMPLE 5 Show that the function f(x) � x 3 � x � 1 has exactly one zero in the, interval [�2, 0]., , 10, , �2, , 2, , �10, , FIGURE 8, The graph shows the zero of f., , Solution First, observe that f is continuous on [�2, 0] and that f(�2) � �9 and, f(0) � 1. Therefore, by the Intermediate Value Theorem, there must exist at least one, number c that satisfies �2 � c � 0 such that f(c) � 0. In other words, f has at least, one zero in (�2, 0)., To show that f has exactly one zero, suppose, on the contrary, that f has at least two, distinct zeros, x 1 and x 2. Without loss of generality, suppose that x 1 � x 2. Then, f(x 1) � f(x 2) � 0. Because f is differentiable on (x 1, x 2), an application of Rolle’s Theorem tells us that there exists a number c between x 1 and x 2 such that f ¿(c) � 0. But, f ¿(x) � 3x 2 � 1 � 1 can never be zero in (x 1, x 2). This contradiction establishes the, result., The graph of f is shown in Figure 8.

Page 22 :

264, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, , 3.2, , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, y, , 1. State Rolle’s Theorem and give a geometric interpretation, of it., 2. State the Mean Value Theorem, and give a geometric interpretation of it., 3. Refer to the graph of f., a. Sketch the secant line through the points (0, 3) and, (9, 8) . Then draw all lines parallel to this secant line, that are tangent to the graph of f., b. Use the result of part (a) to estimate the values of c that, satisfy the Mean Value Theorem on the interval [0, 9]., , 8, 7, y � f (x), , 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0, , 3.2, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 5, , 6, , 7, , 8, , 9, , 10, , x, , EXERCISES, altitude of the plane at time t (in minutes), where 0 � t � 30., Use Rolle’s Theorem to explain why there must be at least, one number c with 0 � c � 30 such that A¿(c) � 0. Interpret, your result., , In Exercises 1–8, verify that the function satisfies the hypotheses, of Rolle’s Theorem on the given interval, and find all values of c, that satisfy the conclusion of the theorem., 1. f(x) � x 2 � 4x � 3;, , [1, 3], , 18. Breaking the Speed Limit A trucker drove from Bismarck to, Fargo, a distance of 193 mi, in 2 hr and 55 min. Use the, Mean Value Theorem to show that the trucker must have, exceeded the posted speed limit of 65 mph at least once, during the trip., , 2. t(x) � x � 9x; [�3, 3], 3, , 3. f(x) � x � x � 2x;, 3, , 2, , [�2, 0], , 4. h(x) � x (x � 7) ; [0, 7], 3, , 4, , 5. f(x) � x21 � x 2; [�1, 1], , 19. Test Flights In a test flight of the McCord Terrier, an experimental VTOL (vertical takeoff and landing) aircraft, it was, determined that t sec after takeoff, when the aircraft was, operated in the vertical takeoff mode, its altitude was, , 6. f(t) � t 2>3 (6 � t)1>3; [0, 6], 7. h(t) � sin2 t;, , [0, p], , 8. f(x) � cos 2x � 1;, , [0, p], , h(t) �, , In Exercises 9–16, verify that the function satisfies the hypotheses of the Mean Value Theorem on the given interval, and find, all values of c that satisfy the conclusion of the theorem., 9. f(x) � x � 1;, 2, , 1, 11. h(x) � ;, x, , 10. f(x) � x � 2x ;, 3, , [0, 2], , 13. h(x) � x22x � 1;, C0,, , 15. f(x) � x � sin x;, , p, 2D, , [0, 4], , C p2 ,, , pD, , sin t, 16. t(t) �, ;, 1 � cos t, , C0,, , 0�t�8, , Use Rolle’s Theorem to show that there exists a number c, satisfying 0 � c � 8 such that h¿(c) � 0. Find the value of, c, and explain its significance., , [�1, 2], , t, 12. t(t) �, ; [�2, 0], t�1, , [1, 3], , 14. f(x) � sin x;, , 2, , 1 4, t � t 3 � 4t 2, 16, , 20. Hotel Occupancy The occupancy rate of the all-suite Wonderland Hotel, located near a theme park, is given by the function, , p, 2D, , 17. Flight of an Aircraft A commuter plane takes off from the Los, Angeles International Airport and touches down 30 min later, at the Ontario International Airport. Let A(t) (in feet) be the, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login., , r(t) �, , 10 3 10 2 200, t �, t �, t � 56, 81, 3, 9, , 0 � t � 12, , where t is measured in months with t � 0 corresponding to, the beginning of January. Show that there exists a number c, that satisfies 0 � c � 12 such that r¿(c) � 0. Find the value, of c, and explain its significance.

Page 23 :

3.2, 21. Let f(x) � 冟 x 冟 � 1. Show that there is no number c in, (�1, 1) such that f ¿(c) � 0 even though f(�1) � f(1) � 0., Why doesn’t this contradict Rolle’s Theorem?, 22. Let f(x) � 1 � x 2>3, a � �1, and b � 8. Show that there is, no number c in (a, b) such that, f ¿(c) �, , f(b) � f(a), b�a, , Doesn’t this contradict the Mean Value Theorem? Explain., 23. Let, f(x) � e, , x2, if x � 1, 2 � x if x � 1, , Does f satisfy the hypotheses of the Mean Value Theorem on, [0, 2]? Explain., 24. Prove that f(x) � 4x 3 � 4x � 1 has at least one zero in the, interval (0, 1) ., Hint: Apply Rolle’s Theorem to the function t(x) � x 4 � 2x 2 � x, on [0, 1]., , 25. Prove that f(x) � x 5 � 6x � 4 has exactly one zero in, (�⬁, ⬁)., 26. Prove that the equation x 7 � 6x 5 � 2x � 6 � 0 has exactly, one real root., 27. Prove that the function f(x) � x � 12x � c, where c is any, real number, has at most one zero in [0, 1]., 5, , 28. Use the Mean Value Theorem to prove that, 冟 sin a � sin b 冟 � 冟 a � b 冟 for all real numbers a and b., 29. Suppose that the equation, anx n � an�1x n�1 � p � a1x � 0, has a positive root r. Show that the equation, nanx n�1 � (n � 1)an�1x n�2 � p � a1 � 0, has a positive root smaller than r., Hint: Use Rolle’s Theorem., , 30. Suppose f ¿(x) � c, where c is a constant, for all values, of x. Show that f must be a linear function of the form, f(x) � cx � d for some constant d., Hint: Use the corollary to Theorem 3., , 31. Let f(x) � x 4 � 4x � 1., a. Use Rolle’s Theorem to show that f has exactly two, distinct zeros., b. Plot the graph of f using the viewing window, [�3, 3] [�5, 5]., 32. Let, f(x) � •, , x sin, 0, , p, x, , if x � 0, if x � 0, , The Mean Value Theorem, , 265, , Use Rolle’s Theorem to prove that the derivative f ¿(x) is, equal to zero at an infinite set of numbers in the interval, (0, 1) . Plot the graph of f using the viewing window, [0, 1] [�1, 1]., 33. Prove the formula, cos2 x �, , 1 � cos 2x, 2, , Hint: Let f(x) � cos2 x � 12 cos 2x. Show that f ¿(x) � 0 on (�⬁, ⬁)., Use Theorem 3 to conclude that f(x) � C, where C is a constant., Determine C., , 34. Suppose that f and t are continuous on an interval [a, b] and, differentiable on the interval (a, b). Furthermore, suppose, that f(a) � t(a) and f ¿(x) � t¿(x) for a � x � b. Prove that, f(x) � t(x) for a � x � b., Hint: Apply the Mean Value Theorem to the function h � f � t., , 35. Let f(x) � Ax 2 � Bx � C, and let [a, b] be an arbitrary, interval. Show that the number c in the Mean Value Theorem applied to the function f lies at the midpoint of the, interval [a, b]., 36. Let f(x) � 2(x � 1)(x � 2)(x � 3)(x � 4). Prove that f ¿ has, exactly three real zeros., 37. A real number c such that f(c) � c is called a fixed point of, the function f. Geometrically, a fixed point of f is a point, that is mapped by f onto itself. Prove that if f is differentiable and f ¿(x) 1 for all x in an interval I, then f has at, most one fixed point in I., 38. Use the result of Exercise 37 to show that f(x) � 1x � 6, has exactly one fixed point in the interval (0, ⬁). What is, the fixed point?, 39. Complete the proof of Rolle’s Theorem by considering the, case in which f(x) � d for some number x in (a, b)., 40. Let f be continuous on [a, b] and differentiable on (a, b). Put, h � b � a., a. Use the Mean Value Theorem to show that there exists at, least one number u that satisfies 0 � u � 1 such that, f(a � h) � f(a), � f ¿(a � uh), h, b. Find u in the formula in part (a) for the function, f(x) � x 2., 41. Let f(x) � x 4 � 2x 3 � x � 2., a. Show that f satisfies the hypotheses of Rolle’s Theorem, on the interval [�1, 2]., b. Use a calculator or a computer to estimate all values of c, accurate to five decimal places that satisfy the conclusion, of Rolle’s Theorem., c. Plot the graph of f and the (horizontal) tangent lines to, the graph of f at the point(s) (c, f(c)) for the values of c, found in part (b).

Page 24 :

266, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, , 42. Let f(x) � x 2 sin x., a. Show that f satisfies the hypotheses of Rolle’s Theorem, on the interval [0, p]., b. Use a calculator or a computer to estimate all value(s) of, c accurate to five decimal places that satisfy the conclusion of Rolle’s Theorem., c. Plot the graph of f and the (horizontal) tangent lines to, the graph of f at the point(s) (c, f(c)) for the value(s) of, c found in part (b)., , In Exercises 45–50, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why it is true. If it is false, explain why, or give an example to show why it is false., 45. Suppose that f is continuous on [a, b] and differentiable, on (a, b). If f ¿(c) � 0 for at least one c in (a, b), then, f(a) � f(b)., 46. Suppose that f is continuous on [a, b] but is not differentiable on (a, b). Then there does not exist a number c in, (a, b) such that, , 43. Let f(x) � x 4 � 2x 2 � 2., a. Use a calculator or a computer to estimate all values of, c accurate to three decimal places that satisfy the conclusion of the Mean Value Theorem for f on the interval, [0, 2]., b. Plot the graph of f, the secant line passing through the, points (0, 2) and (2, 10) , and the tangent line to the, graph of f at the point(s) (c, f(c)) for the value(s) of c, found in part (a)., , f ¿(c) �, , 47. If f ¿(x) � 0 for all x, then f is a constant function., 48. If 冟 f ¿(x) 冟 � 1 for all x, then, 冟 f(x 1) � f(x 2) 冟 � 冟 x 1 � x 2 冟, for all numbers x 1 and x 2., , 44. Let f(x) � sin 1x., a. Use a calculator or a computer to estimate all values of, c accurate to three decimal places that satisfy the conclusion, of the Mean Value Theorem for f on the interval, 2, C0, p4 D ., b. Plot the graph of f, the secant line passing through the, 2, points (0, 0) and 1 p4 , 1 2 , and the tangent line to the graph, of f at the point(s) (c, f(c)) for the value(s) of c found in, part (b)., , 3.3, , f(b) � f(a), b�a, , 49. There does not exist a continuous function defined on, the interval [2, 5] and differentiable on (2, 5) satisfying, 冟 f(5) � f(2) 冟 � 6 on [2, 5] and 冟 f ¿(x) 冟 � 2 for all x, in (2, 5)., 50. If f is continuous on [1, 3], differentiable on (1, 3), and satisfies f(1) � 2, f(3) � 5, then there exists a number c satisfying 1 � c � 3, such that f ¿(c) � 32., , Increasing and Decreasing Functions and the First Derivative Test, Increasing and Decreasing Functions, Among the important factors in determining the structural integrity of an aircraft is its, age. Advancing age makes the parts of a plane more likely to crack. The graph of the, function f in Figure 1 is referred to as a “bathtub curve” in the airline industry. It gives, the fleet damage rate (damage due to corrosion, accident, and metal fatigue) of a typical fleet of commercial aircraft as a function of the number of years of service., , FIGURE 1, The “bathtub curve” gives the number, of planes in a fleet that are damaged as, a function of the age of the fleet., , Fleet damage rate, , y, , Economic life objective, 0, , 2, , 4, , 6, , 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24, , t, , Years in service, , The function is decreasing on the interval (0, 4) , showing that the fleet damage rate, is dropping as problems are found and corrected during the initial shakedown period., The function is constant on the interval (4, 10) , reflecting that planes have few struc-

Page 25 :

3.3, , 267, , Increasing and Decreasing Functions and the First Derivative Test, , tural problems after the initial shakedown period. Beyond this, the function is increasing, reflecting an increase in structural defects due mainly to metal fatigue., These intuitive notions involving increasing and decreasing functions can be, described mathematically as follows., , DEFINITIONS Increasing and Decreasing Functions, A function f is increasing on an interval I, if for every pair of numbers x 1 and, x 2 in I,, x1 � x2, , f(x 1) � f(x 2), , implies that, , See Figure 2a., , f is decreasing on I if, for every pair of numbers x 1 and x 2 in I,, x1 � x2, , f(x 1) � f(x 2), , implies that, , See Figure 2b., , f is monotonic on I if it is either increasing or decreasing on I., , y, , y, y � f (x), f (x1), , f (x2), f (x2), , f (x1), , x1, , 0, , FIGURE 2, , x2, , x, , 0, , y � f (x), , x1, , x, , x2, , (b) f is decreasing on I., , (a) f is increasing on I., , Since the derivative of a function measures the rate of change of that function, it, lends itself naturally as a tool for determining the intervals where a differentiable function is increasing or decreasing. As you can see in Figure 3, if the graph of f has tangent lines with positive slopes over an interval, then the function is increasing on that, interval. Similarly, if the graph of f has tangent lines with negative slopes over an interval, then the function is decreasing on that interval. Also, we know that the slope of, the tangent line at (x, f(x)) and the rate of change of f at x are given by f ¿(x). Therefore, f is increasing on an interval where f ¿(x) � 0 and decreasing on an interval where, f ¿(x) � 0., y, , y � f (x), Slope is negative, , Slope is, positive, , FIGURE 3, f is increasing on an interval, where f ¿(x) � 0 and decreasing, on an interval where f ¿(x) � 0., , 0, , Slope is, positive, , x

Page 26 :

268, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, , These intuitive observations lead to the following theorem., , THEOREM 1 Suppose f is differentiable on an open interval (a, b)., a. If f ¿(x) � 0 for all x in (a, b), then f is increasing on (a, b)., b. If f ¿(x) � 0 for all x in (a, b), then f is decreasing on (a, b)., c. If f ¿(x) � 0 for all x in (a, b), then f is constant on (a, b)., , PROOF, a. Let x 1 and x 2 be any two numbers in (a, b) with x 1 � x 2. Since f is differentiable, on (a, b), it is continuous on [x 1, x 2] and differentiable on (x 1, x 2). By the Mean, Value Theorem, there exists a number c in (x 1, x 2) such that, f ¿(c) �, , f(x 2) � f(x 1), x2 � x1, , or, equivalently,, f(x 2) � f(x 1) � f ¿(c)(x 2 � x 1), , (1), , Now, f ¿(c) � 0 by assumption, and x 2 � x 1 � 0 because x 1 � x 2. Therefore,, f(x 2) � f(x 1) � 0 , or f(x 1) � f(x 2) . This shows that f is increasing on (a, b)., b. The proof of (b) is similar and is left as an exercise (see Exercise 60)., c. This was proved in Theorem 3 in Section 3.2., Theorem 1 enables us to develop a procedure for finding the intervals where a function is increasing, decreasing, or constant. In this connection, recall that a function can, only change sign as we move across a zero or a number at which the function is discontinuous., , Determining the Intervals Where a Function Is Increasing or Decreasing, 1. Find all the values of x for which f ¿(x) � 0 or f ¿(x) does not exist. Use, these values of x to partition the domain of f into open intervals., 2. Select a test number c in each interval found in Step 1, and determine the, sign of f ¿(c) in that interval., a. If f ¿(c) � 0, then f is increasing on that interval., b. If f ¿(c) � 0, then f is decreasing on that interval., c. If f ¿(c) � 0, then f is constant on that interval., , EXAMPLE 1 Determine the intervals where the function f(x) � x 3 � 3x 2 � 2 is, increasing and where it is decreasing., Solution, , We first compute, f ¿(x) � 3x 2 � 6x � 3x(x � 2), , from which we see that f ¿ is continuous everywhere and has zeros at 0 and 2. These, zeros of f ¿ partition the domain of f into the intervals (�⬁, 0) , (0, 2) , and (2, ⬁) .

Page 27 :

3.3, , +++++++++ 0 – – – – – – – 0 ++++++, 0, , x, , 2, , FIGURE 4, The sign diagram for f ¿, y, , Increasing and Decreasing Functions and the First Derivative Test, , 269, , To determine the sign of f ¿(x) on each of these intervals, we evaluate f ¿(x) at a convenient test number in each interval. These results are summarized in the following, table., , y = x 3 � 3x 2 � 2, , 4, 3, 2, , Interval, , Test number c, , f ⴕ(c), , Sign of f ⴕ(c), , (�⬁, 0), (0, 2), (2, ⬁), , �1, 1, 3, , 9, �3, 9, , �, �, �, , 1, �2, , �1 �1, , 1, , 2, , x, , 3, , �2, �3, , FIGURE 5, f is increasing on (�⬁, 0), decreasing, on (0, 2), and increasing on (2, ⬁)., , Using these results, we obtain the sign diagram for f ¿(x) shown in Figure 4. We conclude that f is increasing on (�⬁, 0) and (2, ⬁) and decreasing on (0, 2). The graph, of f is shown in Figure 5., , EXAMPLE 2 Determine the intervals where the function f(x) � x � 1>x is increasing and where it is decreasing., Solution, , The derivative of f is, f ¿(x) � 1 �, , f not defined at x � 0, + + + + + + + + 0– – – –0 + + + + + + + + +, �1, , 0, , x, , 1, , FIGURE 6, The sign diagram for f ¿, , 3, 2, , x, , 2, , �, , (x � 1)(x � 1), x2, , 1, f ¿a� b � �3,, 2, , 1, f ¿a b � �3,, 2, , and, , f ¿(2) �, , 3, 4, , 1, y � x � x_, , 1, , FIGURE 7, The graph of f, , x2 � 1, , giving us the sign diagram of f ¿(x) shown in Figure 6. We conclude that f is increasing on (�⬁, �1) and (1, ⬁) and decreasing on (�1, 0) and (0, 1). The graph of f is, shown in Figure 7.* Note that f ¿(x) does not change sign as we move across the point, of discontinuity., , 4, , �4 �3 �2 �1, �1, , x, , 2, , �, , from which we see that f ¿(x) is continuous everywhere except at x � 0 and has zeros, at x � �1 and x � 1. These values of x partition the domain of f into the intervals, (�⬁, �1), (�1, 0), (0, 1), and (1, ⬁). By evaluating f ¿(x) at each of the test numbers, x � �2, �12, 12, and 2, we find, 3, f ¿(�2) � ,, 4, , y, , 1, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , x, , Finding the Relative Extrema of a Function, We will now see how the derivative of a function f can be used to help us find the relative extrema of f. If you examine Figure 8, you can see that the graph of f is rising to, the left of the relative maximum that occurs at b and falling to the right of it. Likewise, at the relative minima of f at a and d, you can see that the graph of f is falling, to the left of these critical numbers and rising to the right of them. Finally, look at the, behavior of the graph of f at the critical numbers c and e. These numbers do not give, rise to relative extrema. Notice that f is either increasing or decreasing on both sides, of these critical numbers., , *The graph of f approaches the dashed line as x →, be discussed in Section 3.6., , ⬁ . The dashed line is called a slant asymptote and will

Page 28 :

270, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, y, , f (b) � 0, , f (e) does, not exist, , f (c) � 0, f (a) � 0, , FIGURE 8, a, b, c, d, and e are critical numbers, of f, but only the critical numbers a,, b, and d give rise to relative extrema., , 0, , f (d) does, not exist, , a, , b, , c, , d, , x, , e, , This discussion leads to the following theorem., , THEOREM 2 The First Derivative Test, Let c be a critical number of a continuous function f in the interval (a, b) and, suppose that f is differentiable at every number in (a, b) with the possible exception of c itself., a. If f ¿(x) � 0 on (a, c) and f ¿(x) � 0 on (c, b), then f has a relative maximum, at c (Figure 9a)., b. If f ¿(x) � 0 on (a, c) and f ¿(x) � 0 on (c, b), then f has a relative minimum, at c (Figure 9b)., c. If f ¿(x) has the same sign on (a, c) and (c, b), then f does not have a relative extremum at c (Figure 9c)., , y, , y, , y, f (x) > 0, , f (x) > 0, , f (x) > 0, , f (x) < 0, , f (x) > 0, , f (x) < 0, , 0, , (, a, , c, , ), b, , (a) Relative maximum at c, , x, , 0, , (, a, , c, , ), b, , (b) Relative minimum at c, , x, , 0, , (, a, , c, , ), b, , x, , (c) No relative extrema at c, , FIGURE 9, , PROOF We will prove part (a) and leave the other two parts for you to prove (see, Exercise 61). Suppose f ¿ changes sign from positive to negative as we pass through, c. Then there are numbers a and b such that f ¿(x) � 0 for all x in (a, c) and f ¿(x) � 0, for all x in (c, b). By Theorem 1 we see that f is increasing on (a, c) and decreasing, on (c, b). Therefore, f(x) � f(c) for all x in (a, b). We conclude that f has a relative, maximum at c., The following procedure for finding the relative extrema of a continuous function, is based on Theorem 2.

Page 29 :

3.3, , – – – – – – – – – 0 – – – – – – – – – 0 ++++, �2 �1, , 0, , 1, , 2, , 3, , x, , 4, , FIGURE 10, The sign diagram of f ¿, , Increasing and Decreasing Functions and the First Derivative Test, , 271, , Finding the Relative Extrema of a Function, 1. Find the critical numbers of f., 2. Determine the sign of f ¿(x) to the left and to the right of each critical, number., a. If f ¿(x) changes sign from positive to negative as we move across a critical number c, then f(c) is a relative maximum value., b. If f ¿(x) changes sign from negative to positive as we move across a critical number c, then f(c) is a relative minimum value., c. If f ¿(x) does not change sign as we move across a critical number c,, then f(c) is not a relative extremum., , y, , EXAMPLE 3 Find the relative extrema of f(x) � x 4 � 4x 3 � 12., , y � x4 � 4x 3 � 12, , Solution, , 10, , The derivative of f,, f ¿(x) � 4x 3 � 12x 2 � 4x 2 (x � 3), , 0, , �1, , 1, , 4, , x, , �10, (3, �15), , FIGURE 11, The graph of f, , is continuous everywhere. Therefore, the zeros of f ¿, which are 0 and 3, are the only, critical numbers of f. The sign diagram of f ¿ is shown in Figure 10. Since f ¿ has the, same sign on (�⬁, 0) and (0, 3), the First Derivative Test tells us that f does not have, a relative extremum at 0. Next, we note that f ¿ changes sign from negative to positive, as we move across 3, so 3 does give rise to a relative minimum of f. The relative minimum value of f is f(3) � �15. The graph of f is shown in Figure 11 and confirms, these results., , EXAMPLE 4 Find the relative extrema of f(x) � 15x 2>3 � 3x 5>3., f not defined at x � 0, , Solution, , –– – – – – ++++ 0 –– – – – –– – – – –, �2 �1, , 0, , 1, , x, , 2, , FIGURE 12, The sign diagram of f ¿, , 5(2 � x), x 1>3, , f(2) � 15(2) 2>3 � 3(2)5>3 ⬇ 14.29, , y � 15x 2/3 � 3x 5/3, , The graph of f is shown in Figure 13., , 10, , �1, , f ¿(x) � 10x �1>3 � 5x 2>3 � 5x �1>3(2 � x) �, , Note that f ¿ is discontinuous at 0 and has a zero at 2, so 0 and 2 are critical numbers, of f. Referring to the sign diagram of f ¿ (Figure 12) and using the First Derivative Test,, we conclude that f has a relative minimum at 0 and a relative maximum at 2. The relative minimum value is f(0) � 0, and the relative maximum value is, , y, 20, , The derivative of f is, , 1, , �10, , FIGURE 13, The graph of f, , 5, , x, , EXAMPLE 5 Motion of a Projectile A projectile starts from the origin of the xycoordinate system, and its motion is confined to the xy-plane. Suppose the trajectory, of the projectile is, y � f(x) � 1.732x � 0.000008x 2 � 0.000000002x 3, , 0 � x � 27,496, , where y measures the height in feet and x measures the horizontal distance in feet covered by the projectile., a. Find the interval where y is increasing and the interval where y is decreasing., b. Find the relative extrema of f., c. Interpret the results obtained in part (a) and part (b).

Page 30 :

272, , Chapter 3 Applications of the Derivative, , Solution, a. Observe that, dy, � 1.732 � 0.000016x � 0.000000006x 2, dx, is continuous everywhere. Setting dy>dx � 0 gives, 0.000000006x 2 � 0.000016x � 1.732 � 0, Using the quadratic formula to solve this equation, we obtain, , +++++++++ 0– – – – – – – – – –, Å15,709, , 27,496 x, , x�, , FIGURE 14, The sign diagram of f ¿, , �0.000016, , 2(0.000016)2 � 4(0.000000006)(�1.732), 2(0.000000006), , ⬇ �18,376 or 15,709, We reject the negative root, since x must be nonnegative. So the critical number, of y is approximately 15,709. From the sign diagram for f ¿ shown in Figure 14,, we see that y is increasing on (0, 15,709) and decreasing on (15,709, 27,496) ., b. From part (a) we see that y has a relative maximum at x ⬇ 15,709 with value, , 20,000, , y ⬇ 1.732x � 0.000008x 2 � 0.000000002x 3 冟 x�15,709 ⬇ 17,481, 30,000, , 0, , FIGURE 15, The trajectory of the projectile, , 3.3, , c. After leaving the origin, the projectile gains altitude as it travels downrange. It, reaches a maximum altitude of approximately 17,481 ft after it has traveled, approximately 15,709 ft downrange. From this point on, the missile descends, until it strikes the ground (after traveling approximately 27,496 ft horizontally)., The trajectory of the projectile is shown in Figure 15., , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, , 1. Explain each of the following statements: (a) f is increasing, on an interval I, (b) f is decreasing on an interval I, and (c) f, is monotonic on an interval I., , 3.3, , 2. Describe a procedure for determining where a function is, increasing and where it is decreasing., 3. Describe a procedure for finding the relative extrema of a, function., , EXERCISES, , In Exercises 1–6 you are given the graph of a function f., (a) Determine the intervals on which f is increasing, constant,, or decreasing. (b) Find the relative maxima and relative, minima, if any, of f., y, , 1., , 1, 2, �2, , 1, 1 2 3, , x, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login., , y, , 3., , 2, �2, , 2, , �3 �2 �1, , y, , 2., , x, �2 �1, , 1, , 2, , x

Page 31 :

3.3, y, , 4., , y, , 5., , _1, 2, , 1, , �2 �1, , 1, , 2, , �1, , x, , �1, , 17. f(x) � x 1>3 � 1, , 18. f(x) � x 1>3 � x 2>3, , 19. f(x) � x 2(x � 2)3, , 20. f(x) � x 3(x � 6)4, , 1, , x, , 23. f(x) �, 25. f(x) �, , y, , 6., , 1, �1, �1, , 1, , x2, x�1, , 24. f(x) �, , 2x � 3, , 26. f(x) �, , x2 � 4, , y, , 7., , 0.1, �0.1, , 8., , x, , 5, , y, , x �1, x 2 � 3x � 2, x 2 � 2x � 1, , 29. f(x) � x2x � x 2, , 30. f(x) �, , 34. f(x) � sin2 2x,, , 0�x�p, , 35. f(x) � x sin x � cos x,, sin x, , 2x � 1, , 0 � x � 2p, , 0 � x � 2p, , 1 � sin2 x, , x, 2, , 0 � x � 2p, , 33. f(x) � cos2 x,, , ,, , 37. f(x) � tan (x 2 � 1),, 38. f(x) �, , 0.5, , x, 2, , 28. f(x) � x14 � x, , 36. f(x) �, , 273, , x, x�1, , 27. f(x) � x 2>3 (x � 3), , 32. f(x) � x � cos x,, , In Exercises 7 and 8 you are given the graph of the derivative f ¿, of a function f. (a) Determine the intervals on which f is increasing, constant, or decreasing. (b) Find the x-coordinates of the, relative maxima and relative minima of f., , �5, , 22. f(x) �, , 31. f(x) � x � 2 sin x,, , x, , 3, , 1, x, , 21. f(x) � x �, , � _12, , �3, , Increasing and Decreasing Functions and the First Derivative Test, , 0 � x � 2p, , 0 � x � 2p, �p2 � x � p2, , 1, , 0 � x � 2p, 1 � cos x, , 39. The Boston Marathon The graph of the function f shown in, the accompanying figure gives the elevation of that part, of the Boston Marathon course that includes the notorious, Heartbreak Hill. Determine the intervals (stretches of the, course) where the function f is increasing (the runner is, laboring), where it is constant (the runner is taking a, breather), and where it is decreasing (the runner is coasting)., , 20, y (ft), , �4, , �2, , 2, , 4, , x, , Elevation, , 10, , 300, 200, 100, , �10, , 0, , In Exercises 9–38, (a) find the intervals on which f is increasing, or decreasing, and (b) find the relative maxima and relative minima of f., 10. f(x) � �x 2 � 4x � 2, , 9. f(x) � x 2 � 2x, 11. f(x) � x 3 � 6x � 1, , 12. f(x) � �x 3 � 3x 2 � 1, , 13. f(x) � 2x � 3x � 12x � 5, 3, , 2, , 14. f(x) � x 3 � 3x 2 � 9x � 6, 15. f(x) � x 4 � 4x 3 � 6, , 16. f(x) � �x 4 � 2x 2 � 1, , 19.6, , 20.2 20.6 21.1 21.7 21.8, , 22.7, , x (mi), , Source: The Boston Globe., , 40. The Flight of a Model Rocket The altitude (in feet) attained by a, model rocket t sec into flight is given by the function, h(t) � 0.1t 2(t � 7)4, , 0�t�7, , When is the rocket ascending, and when is it descending?, What is the maximum altitude attained by the rocket?

Page 32 :