Page 1 :

sec. 11.2 Reactive Power and Voltage Control 627, , 41.2 REACTIVE POWER AND VOLTAGE CONTROL, , For efficient and reliable operation of power systems, the control of voltage, and reactive power should satisfy the following objectives:, , (a) Voltages at the terminals of all equipment in the system are within acceptable, limits. Both utility equipment and customer equipment are designed to operate, at a certain voltage rating. Prolonged operation of the equipment at voltages, outside the allowable range could adversely affect their performance and, possibly cause them damage., , (b) | System stability is enhanced to maximize utilization of the transmission, system. As we will see later in this section, and in Chapters 12 to 14, voltage, and reactive power control have a significant impact on system stability., , (c) The reactive power flow is minimized so as to reduce RP and XP losses to a, practical minimum (see Chapter 6, Section 6.3). This ensures that the, transmission system operates efficiently, ie., mainly for active power transfer., , The problem of maintaining voltages within the required limits is complicated, by the fact that the power system supplies power to a vast number of loads and is fed, from many generating units. As loads vary, the reactive power requirements of the, transmission system vary. This is abundantly clear from the performance, characteristics of transmission lines discussed in Chapter 6. Since reactive power, cannot be transmitted over long distances, voltage control has to be effected by using, special devices dispersed throughout the system. This is in contrast to the control of, frequency which depends on the overall system active power balance. The proper, selection and coordination of equipment for controlling reactive power and voltage are, among the major challenges of power system engineering., , We will first briefly review the characteristics of power system components, from the viewpoint of reactive power and then we will discuss methods of voltage, , control., 11.2.1 Production and Absorption of Reactive Power, , Synchronous generators can generate or absorb reactive power depending on, the excitation. When overexcited they supply reactive power, and when underexcited, they absorb reactive power. The capability to continuously supply or absorb reactive, power is, however, limited by the field current, armature current, and end-region, heating limits, as discussed in Chapter 5 (Section 5.6). Synchronous generators are, normally equipped with automatic voltage regulators which continually adjust the, excitation so as to control the armature voltage., , Overhead lines, depending on the load current, either absorb or supply reactive, power. At loads below the natural (surge impedance) load, the lines produce net

Page 2 :

628 Control of Active Power and Reactive Power = Chap. 4;, , reactive power; at loads above the natural load, the lines absorb reactive power. The, reactive power characteristics of transmission lines are discussed in detail in Chapter, 6., , Underground cables, owing to their high capacitance, have high natural loads,, They are always loaded below their natural loads, and hence generate reactive powe,, under all operating conditions., , Transformers always absorb reactive power regardless of their loading; at nn, load, the shunt magnetizing reactance effects predominate; and at full load, the serieg, leakage inductance effects predominate., , Loads normally absorb reactive power. A typical load bus supplied by a power, system is composed of a large number of devices. The composition changes, depending on the day, season, and weather conditions. The composite characteristics, are normally such that a load bus absorbs reactive power. Both active power and, reactive power of the composite loads vary as a function of voltage magnitudes. Loads, at low-lagging power factors cause excessive voltage drops in the transmission, network and are uneconomical to supply. Industrial consumers. are normally charged, for reactive as well as active power; this gives them an incentive to improve the load, power factor by using shunt capacitors., , Compensating devices are usually added to supply or absorb reactive power, and thereby control the reactive power balance in a desired manner. In what follows,, we will discuss the characteristics of these devices and the principles of application., , 11.2.2 Methods of Voltage Control, , The control of voltage levels is accomplished by controlling the production,, absorption, and flow of reactive power at all levels in the system. The generating units, provide the basic means of voltage control; the automatic voltage regulators control, field excitation to maintain a scheduled voltage level at the terminals of the, generators. Additional means are usually required to control voltage throughout the, system. The devices used for this purpose may be classified as follows:, , (a) Sources or sinks of reactive power, such as shunt capacitors, shunt reactors,, synchronous condensers, and static var compensators (SVCs)., , (b) Line reactance compensators, such as series capacitors., , (c) Regulating transformers, such as tap-changing transformers and boosters., Shunt capacitors and reactors, and series capacitors provide passive,, , compensation. They are either permanently connected to the transmission and, , distribution system, or switched. They contribute to voltage control by modifying the, network characteristics.

Page 3 :

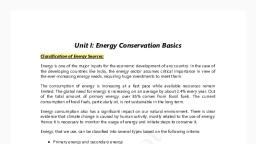

sec. 11.2 Reactive Power and Voltage Control 629, , Synchronous condensers and SVCs provide active compensation; the reactive, ower absorbed/supplied by them is automatically adjusted so as to maintain voltages, of the buses to which they are connected. Together with the generating units, they, establish voltages at specific points in the system. Voltages at other locations in the, system are determined by active and reactive power flows through various circuit, elements, including the passive compensating devices., , The following is a description of the basic characteristics and forms of, application of devices commonly used for voltage and reactive power control., , 41.2.3 Shunt Reactors, , Shunt reactors are used to compensate for the effects of line capacitance,, particularly to limit voltage rise on open circuit or light load., , They are usually required for EHV overhead lines longer than 200 km. A, shorter overhead line may also require shunt reactors if the line is supplied from a, weak system (low short-circuit capacity) as shown in Figure 11.32. When the far end, of the line is opened, the capacitive line-charging current flowing through the large, source inductive reactance (Xs) will cause a rise in voltage Es at the sending end of, the line. The “Ferranti” effect (see Chapter 6, Section 6.1) will cause a further rise in, receiving-end voltage Ep., , , , , , 3 “ e a, E, Xs Es Ex ‘, Of rr }—_ L. —, = CEBV line Ey Es Ep, Weak source ““*, (a) System diagram (b) Phasor diagram, , Figure 11.32 EHV line connected to a weak system, , A shunt reactor of sufficient size must be permanently connected to the line, to limit fundamental-frequency temporary overvoltages to about 1.5 pu for a duration, of less than 1 second. Such line-connected reactors also serve to limit energization, overvoltages (switching transients). Additional shunt reactors required to maintain, normal voltage under light-load conditions may be connected to the EHV bus as, shown in Figure 11.33, or to the tertiary windings of adjacent transformers as shown, in Figure 11.34. During heavy loading conditions some of the reactors may have to, be disconnected. This is achieved by switching reactors using circuit-breakers.

Page 4 :

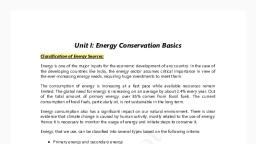

630 Control of Active Power and Reactive Power Chap, 1,, , To weak To strong, system system, , , , , , , , Xpy Xp Ap, , usd, SEL, , Xp) — permanently line-connected reactor, Xp» Xp3 — Switchable bus-connected reactor, , Figure 11.33 Line and bus-connected EHV reactors, , | | To strong, , , , Xpo — permanently line-connected reactor, Xpy, Xp ~ Switchable reactors connected to tertiary, windings of transformers, , Figure 11.34 Line and transformer-connected reactors, , For shorter lines supplied from strong systems, there may not be a need for, reactors connected to the line permanently. In such cases, all the reactors used may, be switchable, connected either to the tertiary windings of transformers or to the EHV, bus. In some applications, tapped reactors with on-voltage tap-change control facilities, have been used, as shown in Figure 11.35, to allow variation of the reactance value., , Shunt reactors are similar in construction to transformers, but have a single, winding (per phase) on an iron core with air-gaps and immersed in oil. They may be, of either single-phase or three-phase construction.

Page 5 :

sec. 11-2 Reactive Power and Voltage Control 631, , rod, , Figure 11.35 Tapped shunt reactor, , 11.2.4 Shunt Capacitors, , Shunt capacitors supply reactive power and boost local voltages. They are used, throughout the system and are applied in a wide range of sizes., , Shunt capacitors were first used in the mid-1910s for power factor correction., The early capacitors employed oil as the dielectric. Because of their large size and, weight, and high cost, their use at the time was limited. In the 1930s, the introduction, of cheaper dielectric materials and other improvements in capacitor construction, brought about significant reductions in price and size. The use of shunt capacitors has, increased phenomenally since the late 1930s. Today, they are a very economical, means of supplying reactive power. The principal advantages of shunt capacitors are, their low cost and their flexibility of installation and operation. They are readily, applied at various points in the system, thereby contributing to efficiency of power, transmission and distribution. The principal disadvantage of shunt capacitors is that, their reactive power output is proportional to the square of the voltage. Consequently,, the reactive power output is reduced at low voltages when it is likely to be needed, most., , Application to distribution systems [25,26], , Shunt capacitors are used extensively in distribution systems for power-factor, correction and feeder voltage control. Distribution capacitors are usually switched by, automatic means responding to simple time clocks, or to voltage or current-sensing, relays., , The objective of power-factor correction is to provide reactive power close to, the point where it is being consumed, rather than supply it from remote sources. Most, loads absorb reactive power; that is, they have lagging power factors. Table 11.1 gives, typical power factors and voltage-dependent characteristics of some common types of, loads,