Page 1 :

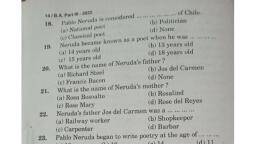

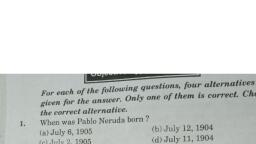

PABLO NERUDA, (1904-1973), I. Introduction to the Poet and his Poetry :, Pablo Neruda (July 12, 1904 – September 23, 1973) was the pen name and the legal name, of the great Chilean poet-writer-politician Neftali Ricardo Reyes Basoalto. Neruda assumed his, pen name as a teenager, partly as a fashionable gesture to assert his individuality and partly to, hide his poetry from his father who wanted his son to have a regular practical occupation., Neruda’s pen name was derived from the Czech writer and poet Jan Neruda., Neruda was accomplished in a variety of styles ranging from erotic poems to surrealist, poetry, historical epics and political prose and poetry. He is considered one of the greatest and, most influential poets of the twentieth century, his work reflecting the material, political and, intellectual concerns of humanity across the western world over the greater part of the twentieth, century. There is an unmistakable vigour about all that he wrote with great conviction., The section on Pablo Neruda in your textbook, Living Literatures contains four poems for, detailed study. The introductory note to this section gives you an account of the highlights and, political landmarks of Neruda’s life. Read that note carefully to get the details right. Then, you, will find this introduction more useful in relating to the special flavour and features of Neruda’s, poetry. Also please note that Neruda’s poetry was written in Spanish. What we read is the, English translation by eminent translators, of the Spanish original. So we must make allowance, for what might appear to be differences in nuance or shades of meaning., Jean Franco in his Introduction to the Penguin edition of the Selected Poetry of Pablo, Neruda tells us that Neruda was the essential poet, bound by a coherent vision of man and the, universe. There is a rare completeness about Neruda’s poetry. It strives to give a voice to, animate and inanimate nature and strives after “a knowledge without antecedents”, a knowledge, of the origins of the beginning of life (in the hitherto underexplored continent of South, America). And yet, Neruda is not merely a poet of nature. He is a man whose poetry bristles, with discontent at the lack of justice and equality on earth. The vision of unalienated man is, pervasive. He would like to see man comfortable, at peace and in harmony with his, surroundings. This vision enables him to become a public poet, to address himself to a, community, not simply as a man speaking to men but as their voice. It is this identification, with a whole culture and a people that enables him to try and decipher the universe. He is a, part of all that he sees around him in the twentieth century. All great poets are a part of their, 1

Page 2 :

times and their psyche and their poetry are shaped by them. The visions of Dante and Milton, were backed by Christianity. Whitman and Hugo derived their energy from the people. In, the twentieth century while Aime Cesaire derives power from “negritude”, Neruda’s source is, the untapped energies of a hitherto disinherited South America., To borrow again from Jean Franco, we must acknowledge that Neruda’s sensibility to, nature is unique in Spanish American poetry. The poet Laureate of the masses is also the poet, of empty space – of America before man. This sensibility was formed by a childhood spent in, the frontier town of Temuco in southern Chile. The region had only recently been opened up at, the turn of the century (19th to 20th century) as a result of a pact with the Araucanian Indians,, the original inhabitants of the region. The Araucanians are the South American Indian group of, Chile., , Presently numbering about 2,00,000, they live in towns, , and cities in, , Chile and, , Argentina. Reading in 2009, we can recognize that the South America of which Neruda writes is, the South America of a hundred years ago. We all read about the depletion of rain forests in, South America in the context of environment and global warming. But Neruda’s response to, encroachment on the forest by progress and civilization is different. His father was involved, with laying out new railway tracks. This job assumes symbolic meaning and can be seen as a, human attempt to transcend the cyclical processes of nature. It is some kind of a victory over, nature. Neruda’s father and stepmother saw the first locomotive, the first cattle and, , the first, , vegetables of that virgin region of damp forest. In other words, they were pioneers in opening up, a new area of human habitation. And Neruda as a ten-year-old in 1914, found this fertile, environment symbolically capable of stimulating his latent creative, poetic talent. So early in, life, Neruda’s choice of vocation was made. He grew up a precocious poet, unhampered by, social and religious convictions or literary ideas deriving intellectual and emotional nourishment, from a virgin landscape of which he seemed the only discoverer. The newness of flora and fauna, left him forever in a state of wonder at the marvels of nature., As he progressed through his teens Neruda’s interest in nature graduated to an interest in, love. At the age of twenty, in 1924, he published Twenty Poems of Love under the pseudonym, (pen name) of Pablo Neruda. This was in no way a mean achievement. We shall later study in, detail, one of these poems, ‘Tonight I Can Write’ which is included in your textbook. But for the, moment it is enough to make a mental note of the fact that these are poems of discovery. They, are about new areas of human experience. They tell of an adolescent’s confrontation of woman, and the universe and his sense of estrangement. In them, the woman merges into nature,, 2

Page 3 :

becomes a part of the earth or mist, with the poet facing her as an explorer and interrogator, defining himself against the universe., The next ten years of Neruda’s life from 1924-34 were years of isolation spent on, diplomatic consular assignments in the East, in Rangoon, Colombo and Java. During this, period Neruda wrote a collection of poems called Residence on Earth. Jean Franco describes, them as “poems which produce a dis-ordering of the world as objects, sense impressions, nature,, are fleetingly glimpsed in their procession towards death.” They are very close to the mood of, our age and reflect the belief that whatever laws exist in the universe, they are not human ones., This decade is followed by some landmark developments in the poet’s life. The low, mood of the Residence collection is replaced by a kind of revival in which order and meaning, again flow into the universe. The process begins in Spain where Neruda as the Chilean consul,, first in Barcelona, then in Madrid, found himself living in a community of poets who had a sense, of their relationship with the people. This is where the poet’s identification with Revolutionary, ideology and communist sympathies evolved. In Residence, Neruda had expressed a sense of, isolation. He had lost any sense of another’s presence, his dialogue being with a dying, universe. Now, his world suddenly got filled up with people whom he wanted to communicate, with. This desire to relate to a larger community led to the subsequent composition of the, Chilean epic that would turn into the Canto General (1950)., After the publication of Canto General in 1950, Neruda became increasingly preoccupied, with clarity, with the communication of his poetry to a non-literary public and this led him to the, composition of his Elemental Odes. These poems of short lines mark a development away from, the ceremonial and from oratory. The poem that is included in your syllabus from this, collection is entitled “Ode to the Clothes”. These poems suggest an art as close as possible to, life. They are a homage to daily living, to ordinary people and objects. They celebrate bread,, wood, tomatoes, the weather, clothes and the elements. They are about mundane activities of, daily life in a pre-industrial world. The odes seem to restore a sense of the wholesomeness of, work and seem to express the poet’s approval of this way of life. It is also a poetic recall of, Neruda’s childhood and the community in which he grew up. It also reinforces Neruda’s view, of poetry as a social act., With a repertoire of love poetry, nature poetry, poetry of social commitment, already, achieved, Neruda moves on to yet another kind of poetry. In some of the poems in the, , 3

Page 4 :

collection Estravagoria (1958), he has resorted to the mythical or the fabulous as in the “Fable, of the Mermaid and the Drunks” which is included in the textbook prescribed for this course., As we move into the 1960s, we must note that the poet seems to experience a kind of, peaceful home-coming. He writes about Chile, its natural beauty, the ocean, his house at Isla, Negra. Neruda seems to be in communion with the natural world. The collection entitled “The, Stones of Chile” was published in 1961 and the single poem included in your textbook is “The, Portrait in the Rock”. The poet takes us back to the exploration of the mystery of nature. It is as, if on a shrinking planet, Neruda wishes to restore a sense of wonder, of the sacredness of the, natural world. So he sees the stones of Chile not only as material to be used in human, construction but as “mysterious, unearthly matter”, planetary in origin and eloquent of a universe, unknown to man., It is hoped that this introductory note will help you to locate the finer points and nuances, of Neruda’s poetry fairly early in your study of the poems in your course. Of course, you need, to read the poems several times to understand their full complexity. But, rest assured, it will be a, very rewarding experience., , II., , His Work : The Poems, , (i), , Having started early in life, Neruda composed poetry over a span of more than fifty, years. But the most popular poems have been those of Love, especially the ones, published in the 1924 collection of Twenty Poems of Love. Highly physical in nature,, they are more about sex than about love but Neruda manages to achieve the sensation of, pure lyricism in them., Traditionally, love poetry has equated woman with nature. Neruda manages to take this, established mode of comparison to a cosmic level, making woman into a force of the, universe. Critics and scholars tried hard to track the women who were the inspiration, for these poems of Neruda’s youth. Neruda vaguely provided an explanation saying the, two were Marisol and Marisombra. You can see that the two names are generic in, nature., , Marisol is the idyll of the enchanted province, the beautiful countryside., , Marisombra (the serious one) is the student who lived and studied in the city of Santiago, where Neruda too was a student. She wears a gray cap, has soft eyes and is the picture, of nomadic student love. Subsequent research did manage to locate one Albertina Rosa, as the object of Neruda’s affections during that phase., 4

Page 5 :

Tonight I can write, , Tonight I can write the saddest lines., Write for example, ‘The night is shattered, And the blue stars shiver in the distance.’, The night wind revolves in the sky and sings., Tonight I can write the saddest lines., I loved her, and sometimes she loved me too., , 5, , Through nights like this one I held her in my arms., I kissed her again and again under the endless sky., She loved me, sometimes I loved her too., How could one not have loved her great still eyes., , 10, , Tonight I can write the saddest lines., To think that I do not have her. To feel that I have lost her., To hear the immense night, still more immense without her., And the verse falls to the soul like dew to the pasture., What does it matter that my love could not keep her., The night is shattered and she is not with me., , 15, , This is all. In the distance someone is singing. In the distance., My soul is not satisfied that it has lost her., My sight searches for her as though to go to her., My heart looks for her, and she is not with me., , 20, , The same night whitening the same trees., We, of that time, are no longer the same., I no longer lover her, that’s certain, but how I loved her., My voice tried to find the wind to touch her hearing., Another’s. She will be another’s . Like my kisses before., Her voice. Her bright body. Her infinite eyes., I no longer love her, that’s certain, but maybe I love her., Love is so short, forgetting is so long., 5, , 25

Page 6 :

Because through nights like this one, I held her in my arms, My soul is not satisfied that it has lost her., , 30, , Though this be the last pain that she makes me suffer, And these the last verses that I write for her., Translated by W.S. Merwin, Annotations, Tonight I Can Write . . ., 3. blue stars: the constellations are blue because of their searing heat and their distance in the, indigo skies, 4. revolves : rotates, sings : the sound of the whistling winds, 7, , this one: the present; “one” strikes the note of universality, , 10 great still eyes: the sight of the woman/nature records the silent depths of the environment, 13 To hear the immense night: to absorb the silence and loneliness of the surroundings in the, absence of the lover/companion, more immense: great emptiness that comes from loss, 14 verse falls to the soul: poetry of separation wells up in the heart, like dew to the pasture: soft, moist water droplets upon the green fields, 15 keep: hold, 19 My sight : gaze is both internal and external, 21 night whitening the same trees: the moonlight casts its silvery white light upon the trees. A, moonlit night is significant for lovers, even in their separation; see Shakespeare’s play The, Merchant of Venice (Act V, Scene i, ll.1-22)., 23 I no longer…: note the opposition of past and present, 24 touch her hearing: impinge upon her conscience/memory. This is a deliberate intermix of the, senses, 25 Another’s: belonging to someone else, another man’s woman, 26 bright: young and vigorous, Infinite eyes: eyes that are profound and deep and seem to go on forever in the poet’s, memory, 31 the last pain: the pain of parting when the relationship has ended, 32 last verses: final time she is commemorated in his poetry, , 6

Page 7 :

The poem prescribed for your study is the last and the longest of the twenty love poems., It is about the sadness that comes with the closure of a relationship. But, according to the, eminent Neruda scholar, Rene de Costa, the real subject of this composition is not the speaker’s, stated sadness but the disparity between his sentiment and the words he can summon to express, what he feels. The poem with thirty-two lines is organized as a series of statements of sadness, and frustrated attempts to deal with this feeling poetically., The initial line, “Tonight I can Write the saddest lines”, is a declaration of intention and, even of capability and is repeated several times. On every occasion, the point of departure from, one stage is a chance to write about another stage of the relationship. For instance “I loved her,, and sometimes she loved me too.”, And then “She loved me, sometimes I loved her too.”, Again, compare lines 23-24 and 27-28, “I no longer love her, that’s certain, but how I loved her., My voice tried to find the wind to touch her hearing”., is subtly different from, “I no longer love her, that’s certain, but may be I love her., Love is so short, forgetting is so long”., The poem’s effectiveness, the reader’s empathy with the sincerity of the poetic voice, derives from the fact that this is a composition like no other. Neruda has employed here a, rhetoric that is not conventionally poetic., , The staggered rhetoric of this poem is not a, , conventional poetic tool. The prosaic syntax too is unusual. But these new features add to the, appeal of the poem whose subject matter is already different., The poem has a lyricism of imagery and sentiment heightened by its cosmic background the sky, the stars, the wind, the night and the sense of infinity. The dimension of time past and, time present also adds to the sincerity of intent which the poet wishes to convey. And of, course, we cannot miss the spatial and sensual imagery which gives it its “poetic” quality - the, endless sky, someone singing in the distance, her bright body, her infinite eyes….., The annotations and this commentary should have enabled you to read this poem, meaningfully. They might even raise certain questions in your mind. For instance, are Neruda’s, lines the saddest lines anyone can write in his situation ? Or, for that matter, what do you think, of the constancy/inconstancy of the poet’s love for the girl ? While you mull over these, , 7

Page 8 :

questions in your mind, we will try and answer the questions asked in your text book for which, you may turn to p.136 of Living Literatures., , Q1. Explore the ways in which the poet talks of his sadness in the context of nature., A. The poem is set against the night which is, by its very nature, an expanse of darkness,, sadness, insecurity, the invisible and the incomprehensible. The absence of light itself, generates negative emotions., movement heightens the, , In the poem, this phenomenon of the cycle of cosmic, , effect of the poet’s love being followed by the end of that, , experience of love. Whatever bright spots (stars) there are, they are very distant, just like, the poet’s feelings of love which are now a thing of the past far removed from his memory, and consciousness. They reappear as remotely as the blue stars that shiver in the distance., The term ‘shiver’ even reinforces the coldness of the poet’s sentiments., The full moon shines with the same brightness, whitening the same trees (line 21) but the, lovers are no longer the same. The human, the temporal has changed even though the natural, processes continue at their own pace which is governed by the laws of the cosmos., , Q 2. How are the man and the woman “no longer the same” while the night is the same ? Is that, why the poet is sad ?, A., , The night is the same because it is a cosmic phenomenon whose properties remain the same, - an enveloping darkness broken only by the moonlight as the moon moves through the, lunar cycle. The night here does not refer to a specific night in the chronological sense but to night in the sense of any night which follows any day in a span of twenty four hours, - a period of darkness followed by a period of daylight, forever and ever., The man and the woman are no longer the same because their feelings towards each other, have changed. Their love is no longer what it was before., The poet is sad because no matter how hard he tries, he finds it difficult, first to understand,, and then to put in words, the experience of loving and losing. “My soul is not satisfied, that it has lost her,” he says., , Q.3. Discuss the ways in which the lyric form enables the poet to explore his emotions that are, at once personal and universal., , 8

Page 9 :

A., , In the most common use of the term, a lyric is any fairly short poem consisting of the, utterance by a single speaker, who expresses a state of mind or a process of perception,, thought and feeling. Most poets represent their protagonists as musing in solitude like, Neruda in this poem. Within the lyric, the process of observation, thought, memory and, feeling may be organized in a variety of ways. In this particular poem, Neruda uses simple, words repeatedly to express a, universal quality, he uses the, , feeling as universal as love. To further enhance its, backgrounds of nature in its visible/invisible,, , audible/inaudible manifestations. He tries to see in the dark and to catch the sounds in the, silent right. The poet, his love, his feelings, are all one with nature., , Q4. A number of lines and words are repeated in this poem. What is the effect of this, repetition?, A., , Repetition works in more than one way. It enhances the musical quality of the verse, making it more appealing to the common reader. Also, it reinforces the feeling of sadness, for a lost love which is the theme of the poem., , Q5. “My sight” is both external and internal. Comment on the ways the verse traverses both, kinds of spaces., A. “My sight searches for her as though to go to her., My heart looks for her, and she is not with me.”, External space is the physical world outside the mind and the heart of the poet. That is, where he looks for her physical presence (metaphorically) imagining that she might just be, present somewhere and he might encounter her., Internal space refers to the world of emotion of which the heart is the seat. When the poet, looks within, introspects, he faces the harsh truth that the bond of love no longer exists., This is the sad realization which the poet faces when he “looks within”. This set of lines, covers both spaces with consummate ease., , 9

Page 10 :

(ii), , The next poem we are required to study is the ‘Ode to the Clothes’ which is taken from, , Ode Elementales which was published in 1954. After the publication of Canto General in 1950,, Neruda became increasingly preoccupied with clarity and addressing his poetry to a non-literary, public. This was facilitated by a natural and remarkable ability to shed an exhausted poetic style, and move on to a new one, much like a snake effortlessly sheds its skin., The Ode is a classical poetic form. The prototype was established by the Greek poet, Pindar whose odes were modelled on the songs by the chorus in Greek drama. Pindar’s odes, were encomiastic; that is, they were written to praise and glorify someone. In the English Odes, modelled on the Pindaric Ode, poets also eulogized something: a person (Dryden’s “Anne, Killigrew”), or the arts of music or poetry (Dryden’s “Alexander’s Feast”) or the time of day, (Collins’ “Ode to Evening”), or, , abstract concepts (Gray’s “Hymn to Adversity” and, , Wordsworth’s “Ode to Duty”)., Neruda’s odes mark a development away from the ceremonial and from oratory towards, a poetry intended to be as natural as song. This is art as close as possible to life. The Odas are, brutally simple poems, strings of lines sometimes only three syllables long, sometimes, containing only one word. The effect is to force breath stops on the rhythm where they would, not normally occur, sometimes for suspense preceding a surprise image, always in order to, maintain a fresh pace. The effect is heightened by the visual signal of a uniform left hand, margin and the blankness of the page beyond the words, setting them apart as having been, especially chosen. Neruda’s Odes have often been seen as a new and evolved version of the, classical ode which too was the chosen form for civic poetry. Here, the subjects of the odes are, very ordinary and ‘elemental’ to life : bread, an onion, a tomato, almost anything., When he received the Nobel Prize in 1971, Neruda said that poetry involved achieving a, proper balance “between solitude and solidarity, between feeling and action, between the, intimacy of one’s self, the intimacy of mankind, and the revelation of nature”. These odes are a, manifestation of Neruda’s intimacy with mankind in the widest sense. A critic, Nancy Willard, describes these odes as “Neruda’s hymns to being alive”. Other critics have commented on the, inherently unpoetic nature of Neruda’s subjects. But while most good poets simply avoid, Neruda’s subject, Neruda renders a poem into a poetic recipe manipulating images and, rhythms., 10

Page 11 :

In ‘Ode to the Clothes’ the poet uses personification very effectively as a poetic, technique to bring out both, his unpoetic subject and his social doctrine, in a rather dramatic, framework. It is almost a stage set, the clothes waiting over a chair in the poet’s room, the poet, emerging from a washroom and putting on his clothes. There are even sexual overtones in the, intimacy of the legs of the trouser covering up the poet’s legs in an embrace of “unwearying, fidelity”. His social doctrine enters the poem in the form of the image of a shootout when, the, poet imagines, a revolutionary like himself might be shot dead, covering his clothes with his, blood. The entire poem is built around a rather funny but intimate, almost personal relationship, of loyalty unto death between the clothes and the poet – a man actively involved in political, activity in contemporary Latin America., Apart from personification, Neruda uses the technique of catalogue structure. Catalogue, – the enumeration of objects falling under the category of the subject of his poem, serves an, important purpose. It amplifies the effect of the poem through both, imagery and rhythm. That, is how a poem of seventy lines is created over as mundane a subject as ‘clothes’., When the humorous tone is added to personification and catalogue, the results are, dramatic. You can visually imagine the poet interacting with the clothes which seem to have a, life of their own, billowing out in the wind, bursting at the seams and pushing out their elbows., Critics of Neruda’s poetry have also identified the use of foil as a poetic device. A foil is, a contrast and can create a dialectic within the poem. A dialectic is a systematic reasoning,, exposition, or argument that juxtaposes opposed or contradictory ideas and seeks to resolve their, conflict. In the ‘Ode to the Clothes’ the basic dialectic seems to be between the inanimate, clothes and the highly evolved, vain, hopeful, live protagonist., The purpose of prefacing the poem. ‘Ode to the Clothes’ with these observations is to, enable you to look for these aspects in the very first reading of the poem itself., Ode to the Clothes, Every morning you wait,, clothes, over a chair,, for my vanity,, my love,, my hope, my body, , 5, , to fill you,, I have scarcely, 11

Page 12 :

left sleep,, I say goodbye to the water, and enter your sleeves,, , 10, , my legs look for, the hollow of your legs,, and thus embraced, by your unwearying fidelity, I go out to tread the fodder,, , 15, , I move into poetry, I look through windows,, at things,, men women,, actions and struggles, , 20, , keep making me what I am,, opposing me,, employing my hands,, opening my eyes,, putting taste in my mouth,, , 25, , and thus,, clothes,, I make you what you are,, pushing out your elbows,, bursting the seams,, , 30, , and so your life swells, the image of my life., You billow, and resound in the wind, as though you were my soul,, , 35, , at bad moments, you cling, to my bones, empty, at night, 12

Page 13 :

the dark, sleep,, , 40, , people with their phantoms, your wings and mine., I ask, whether one day, a bullet, , 45, , from the enemy, will stain you with blood, and then, you will die with me, or perhaps, , 50, , it may not be, so dramatic, but simple,, and you will sicken gradually,, clothes,, , 55, , with me, with my body, and together, we will enter, the earth., At the thought of this, , 60, , every day, I greet you, with reverence, and then, you embrace me and I forget you, because we are one, , 65, , and will go on facing, the wind together, at night, the streets or the struggle,, one body,, maybe, maybe, one day motionless., , 70, Translated by W.S. Merwin, 13

Page 14 :

Annotations :, Ode to the Clothes, Lines 1-10 : All the activities of early morning which culminate in the poet getting dressed and, ready for the day are listed here., Lines 10, 12 : Personification : your sleeves, your legs, Line 15 : to tread the fodder : an activity related to farming – an elemental occupation very basic, to human existence, Line 16 : move into poetry : get into the mode of intellectual and creative work, composing,, writing, thinking about human life all around., Line 20-30 : Just as the poet’s actions are caused by the life around him, his clothes receive, their impetus from the poet. His movements give substance to his clothes as in a, shirt elbow strained with movement., Line 31-32 : Clothes fed the poet’s vanity at the beginning of the poem; here they echo the, workings of his mind and body (as though they were his soul)., Line 43-59 : Thoughts of death in which clothes are his constant companions, Line 60-70 : At first, reverence, and then an unselfconscious acceptance of oneness between the, poet and his clothes., , After the introductory comments and the annotations, if there are still any gaps in your, understanding of this easy and enjoyable poem, maybe the questions asked after the poem will, help you out. Please refer to p.139 of your textbook., Q1. What are clothes associated with in the poem ? What do they enable the poet to do ?, A., , Clothes are associated with the poet’s vanity, his love, his hope and his body which needs, an outward protection and cover. In other words, they are the external cover for his core, personality, his psyche, his mental make up. Being a manifestation of a man’s social, status as also a necessary attribute of a man’s social presentability, acceptability and, conditioning, clothes enable him to go out and interact with the world., , Q2. Why does the poet compare clothes to his soul ?, , 14

Page 15 :

A., , The soul is an unseen but sentient presence in human beings, capable of tremendous, agitation and also of feelings of extreme peace. The poet’s clothes are capable of, physically showing signs of the same feelings. At times they are filled out (bursting at the, seams) with the poet’s energy, both mental and physical. At other times they collapse and, cling to his physical body, withdrawn and shut off from the world., , Q3. How will the clothes die with the poet ?, A., , The poet imagines a public death for himself., , If he is shot violently for being a, , revolutionary, his clothes will share his death. If he dies of sickness, then too, he will be, buried dressed; so his clothes will accompany him to the grave., , Q4. Discuss how Neruda refers to the history of blood and struggle of the Latin Americas, through this simple Ode., A., , From line 17 onward, “I look through windows” the hints of revolution can be felt. He, watches men, women, actions and struggles. The tone indicates that these actions are not, mundane or pastoral. There is struggle, political struggle. The unease of the poets mind, has already been indicated in lines 7-10 where the poet has scarcely left sleep, said, goodbye to the water (had a bath) when he gets into his clothes, ready for the day., The highs and the lows of revolutionary movements are indicated in the puffed and, , billowing clothes which resound in the wind being followed by despair indicated by clothes, clinging to his bones. And the sleep he mentions is not peaceful; it is dark night and people are, with their phantoms., The most obvious reference to blood and killing is the imagined likelihood of being shot, on the street and dying a bloody but dramatic death., Even in this seemingly simple poem, overtones of contemporary violence leave their, mark., All these questions and answers should enable you to see the Ode to the Clothes in its, proper perspective as a simple poem with hints of deeper more serious issues preoccupying the, poet’s mind., And we would like to leave you asking yourself some questions too., a) Is there any evolution in the poet by the time we reach the conclusion of the poem ?, b) Is there any realization at the end of the poem ?, 15

Page 16 :

c) Does the poem end on a celebratory note ?, Think out your answers., , (iii), , ‘The Fable of the Mermaid and the Drunks’ is the third poem by Pablo Neruda included, , in our anthology. The note in the textbook tells us that it is taken from a collection of poems, published in 1958 under the little of Estravagario. In order to see the poem in its proper, perspective let us see what an eminent critic Rene’ de Costa* has to say about the collection:, “Estravagario is important not so much for its political or personal revision of the past as for its, successful adaptation of what has come to be called anti-poetry”. Earlier, we had observed how, Neruda has a remarkable capacity to move effortlessly on to new poetic styles, once an earlier, one is exhausted., , In this collection, he began a whole new stage in his own poetry and, , contributed to the public acceptance of a radically different type of literary expression., It is essentially a colloquial (based on local language) mode of literary discourse, more, chatty and less reasoned than the elemental odes. We can see that the poet has revised his, attitude to the function of his work and his role as a poet. He is a man talking to men. Unlike in, the odes, he takes a look at himself as a poet and as a man and talks freely to his readers as, though to a circle of good friends gathered for a witty after-dinner conversation. The assumption, is that we share not only his concerns but his droll sense of humour as well. He not only refuses, to take himself seriously, he also presents his work in such a way as to challenge the reading, public’s sense of decorum. As the title suggests, the book is an extravaganza of sorts, containing, a miscellany of literary texts both serious and comic., A fundamental breakthrough in Estravagario is that Neruda recognizes poetry as, entertainment. Poetry need not always be solemn. Whether it is printed in newspaper columns, or in volumes, poetry is read primarily for aesthetic pleasure. Recognizing this literary fact of, life, the author does not preach. He simply appeals to our minds, entertaining us for a while., As in watching a stage performance, we are simply required to forget about the real world and, enjoy the narrative. The reader viewer is thus guided into the total imaginative structure, provided by the author. In this way, the extra ordinary does not become ordinary; it is kept, extra ordinary. It remains playful and the poet/entertainer continues to perform., *, , Rene de Costa, The Poetry of Pablo Neruda, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University, , Press, 1979., 16

Page 17 :

It is against this backdrop that we shall study the fable called “The Mermaid and the, Drunks”. We are told that the poem is built upon the mythical and the fabulous. A myth, in its, most basic sense, is any story or plot whether true or invented. Such a story serves to explain, and provide a rationale for social customs and observances and rituals. Similarly, a fable is a, narrative in which things irrational and sometimes even inanimate are, for the purpose of moral, instruction, made to behave with human interests and passions. The intention is to instruct or, amuse. In Neruda’s poem, we find some mythical traits along with some from the “fable”., And the intention is more to amuse than to instruct in this story of uncouth lust told in a new, poetic form., Fable of the Mermaid and the Drunks, All these men were there inside, When she entered, utterly naked., They had been drinking, and began to spit at her., Recently come from the river, she understood nothing., She was a mermaid who had lost her way., , 5, , The taunts flowed over her glistening flesh., Obscenities drenched her golden breasts., A stranger to tears, she did not weep., A stranger to clothes, she did not dress., They pocked her with cigarette ends and with burnt corks,, , 10, , And rolled on the tavern floor with laughter., She did not speak, since speech was unknown to her., Her eyes were the colour of faraway love,, Her arms were matching topazes., Her lips moved soundlessly in coral light,, , 15, , And ultimately she left by that door., Scarcely had she entered the river than she was cleansed,, Gleaming once more like a white stone in the rain;, And without a backward look, she swam once more,, , 20, , Swam toward nothingness, swam to her dying., Translated by Alastair Reid, , 17

Page 18 :

Note, The poem, taken from Estravagiro (1958), is built upon the mythical and the fabulous. The poet, contrasts the mermaid and the drunks, the poetical and the profane, imagination and reality,, beauty and ugliness. The ‘fable’ in the title points to this juxtaposition, the cleft in between, that, the reader is supposed to inhabit. The mermaid is of the earth and river, connected to nature,, while the drunks are her opposite. She is woman, they men., Annotations, The Fable of the Mermaid and the Drunks, L1. inside: inside a tavern, a drinking place, L5. mermaid: a mythical creature of the river, halfwoman and half fish, L7. Obscenities drenched her golden breast : probably true in both the literal and the, metaphorical sense. May be liquor was poured over her in a gesture of vulgarity., L10 Pocked : marked with blisters or pustules resulting from burns or disease. Pock-marked as, from smallpox., L14 topaz: transparent yellow precious stone., L 15. coral light: it is the lips of the mermaid which are the colour of coral., L 17. cleansed: restored to an earlier state of purity. Cleansing is metaphorical and spiritual as, compared to cleaning which is physical. There are also overtones of a return to a prelapserian state of innocence, the state of man before the fall as narrated in the Bible., L 18. white stone : reinforces the idea of purification, L 19 backward look : looking back, L 20 to her dying : conveys a sense of a final departure from the world of men and their ugliness, as compared to nature and the river, Commentary :, Throughout your reading of this poem you must keep in mind the fact that like other, poems in Estravagario this too is an exercise in playfulness. Some critics say the subject of the, poem derives from Matilde Urrutia, the wife with whom he spend the last two decades of his, life. But there is no agreement among critics on this matter. However all agree that Neruda is, writing light heartedly and not taking himself seriously., Although the translation of the poem printed in your book is punctuated, the original, Spanish version is an unpunctuated poem with a non-stop narrative delivery. Whether or not, Matilde is the subject, the parameters of the poem are not in the purview of reality and personal, 18

Page 19 :

experience but of the imagination. Neruda has abandoned literary realism. Freed of his social, political and literary past, he revels in the colloquial idiom of the anti-poem, playing around, with rhyme and words and imagery., The mermaid of fable and myth is a creature who is half woman and half fish. Neruda’s, mermaid, not being human, is “utterly naked” and arouses the “drunks”, uncouth and vulgar in, their behaviour, spitting at her. She seems like a creature from the pre-lapserian world of the, Biblical garden of Eden. Innocent and uncomprehending of the behaviour of the drunks, “she, understood nothing. She simply seems to have lost her way and the vulgar taunts and obscene, comments don’t affect her because she does not understand them.”, But the poet is not as superficial as he would like us to believe. When he says “A, stranger to tears, she did not weep. A stranger to clothes, she did not dress”, the unsaid meaning, is that it was an occasion when male brutality might have been a reason to cry. The cruelty, inherent in human nature is brought out in their pocking her with burnt cigarette ends and corks., (Wine bottles are often sealed with cork lids to prevent flavours from getting spoilt). Their, rolling on the tavern floor with laughter is socially unacceptable behaviour but she does not, speak because speech is unknown to her. The “Drunks” and the “Mermaid” are two extremes, and the reader is somewhere between the two. She sees but not what is immediately before, her; “her eyes were the colour of faraway love”. Her bright arms are simply “matching, topazes” (beautifully precious) but they are not flailing in protest against the “Drunks”. Nor, are they outstretched in longing for her “faraway love”. Her “coral pink” lips move soundlessly, saying nothing. And then she leaves to enter the river, her home., The last four lines of the poem leave you wondering if Neruda’s mood has gradually, turned spiritual., , Does her “cleansing” as soon as she enters the, , river have spiritual, , connotations? She is washed clean and swims on. What is she washed clean of ?, Defilement? What is she swimming toward ? Nothingness ? When the poet talks of her, swimming to her death is he talking about the individual’s journey through life against the, backdrop of nature ? Is he looking at the river of life ? Has an ordinary subject related to human, misdemeanour generated philosophical thoughts even at a subconscious level ?, Turn these questions over in your mind., Finally, turn to p.140 of your text book., , Q1. What does the mermaid look like ?, 19

Page 20 :

A., , The mermaid, half woman and half fish, looks like a creature who has lost her way and, reached a tavern full of uncouth drunken men., , Q2. How did the drunks treat her ?, A., , The drunks treated her in a vulgar, obscene and cruel manner. They were vulgar in spitting, at her, obscene in describing and commenting on her beauty, her “golden breasts”, and, cruel in hurting and burning her with cigarette butts and cork stoppers (from their bottles, of liquor)., , Q3. What does the mermaid symbolize ?, A., , She symbolizes the beauty and innocence of nature as contrasted with the corruption of, human nature as depicted by the drunk men., , Q4. Discuss the significance of words like ‘Coral’, ‘topaz’, ‘stone’, in the poem. Are they in, any way connected to the river from which the mermaid came ?, A., , Inanimate and animate things co-exist in nature. “Coral” is a hard substance usually, containing calcium produced by certain marine invertebrates (animals related to the sea)., “Topaz” is a mineral, a transparent, crystalline stone used as a gem. Yellow sapphire is, formally known as topaz., , “Stone” is something we are all familiar with. All are non-, , living although coral is produced by sea-life. Yet, all three wash themselves clean in the, river and can flow into it like the mermaid, almost going home to nature like human, beings, especially sensitive ones like poets, a return reminiscent of Neruda’s return to Chile, in his later years., , 20

Page 21 :

(iv) The Portrait in the Rock, As we approach the last poem by Neruda in your anthology, I am sure you have a fairly, good idea of the range of his poetry from the personal to the socio-political. You might also, have noticed the poet’s love for his native land, its people, and the political well being of its, polity. Your book tells you that this poem is from the collection called ‘The Stones of Chile’,, (published 1961). We all know that Neruda wrote about the flowers, the birds, the mountains of, Chile. Right from his twenties, Neruda lived in various parts of the world in consular capacities, but after a, , career of involvement in political conflicts and political ideologies, especially, , communism, his return to Chile was an emotional homecoming., His sympathy for revolutionaries and dissenters was remarkable. He observed and, experienced the Spanish Civil War (1936-9). The ‘Republicans’ included moderates, socialists,, communists and anarchists., , The ‘Nationalist’ insurgents included monarchists, Carlists,, , Conservative Catholics and fascist Falangists. The armed forces were divided. Some years, later, he began to take an active interest in the politics of Chile. From 1945 when he was, elected senator and joined the Communist party, he was constantly involved with workers and, ordinary people. Unafraid to express dissent, in 1948 he protested against the then Chilean, President, Gonzalez Videla, who despite being backed (as a candidate) by the communist party,, broke off relations with several then communist east European countries. Neruda found himself, threatened with arrest and went into hiding moving from house to house, sheltered by workers, and country people. A poem, ‘The Fugitive’ is devoted to this experience in which he shared the, homes of workers for whom his poetry was intended., These details are intended to give you some idea of the depth of empathy with the, revolutionary whose face Neruda imagines he can see in ‘The Portrait in the Rock’., So much for the ‘Portrait’. What about the ‘Rock’? Don’t forget that the poem is from, the collection called. The Stones of Chile. After living abroad for many years, when Neruda, decided to settle down in Isla Negra, he was clearly keen to enjoy the natural beauty of his, mother country. Chile is a country along the narrow coastal belt on the west side of the, continent of South America. Its geographical location is similar to that of Kerala in India., Chile is backed by the Andes mountains in the north so Neruda had first hand experience of rock, terrain., , 21

Page 22 :

‘The Portrait in the Rock’ is a poem about a man who was tired and disillusioned with, life in Paraguay (another South American country). He eventually left his country of origin, his, home and family and went into self-exile in a foreign land. The autobiographical note is, unmistakable. Life in a foreign land was not every comfortable. He (the central figure of the, poem) ran into trouble and was beaten up as he was an illegal immigrant. It was a life of being, on the run and hiding from authorities. His friend, the one narrating the poem, sees him years, later but already as a monument in stone erected in his country of origin., Neruda does not give the name of the person being talked about in the poem. He simply, calls him a friend. This piece of poetry is very simple and has a flow which reflects the flow of, the narrative. Neruda does not give the man a name as the portrait is seen as an artistic, embodiment of what the travails of a revolutionary life do to a man. They sap him of life and, energy and bring on an early death. The empathy in Neruda’s story makes us feel that the story, is real and Neruda delves deep into his character., In discussions on poetry, a term that often crops up is “self-projection”. The transfer of a, poet’s own traits of character, ideas, opinions to a literary/poetic character created by the poet,, is known as self projection., , So, the portrait of the Revolutionary in the rock is both, a, , biographical projection and a self-projection of the poet. In addition, it is a historical record of a, real life lived in the turbulent phases of political strife in South America in the twentieth century., Just as the friend was from Paraguay, Neruda was from Chile, a committed Communist, hounded by the then Chilean government. Later, in the years before his death, Neruda was a, close collaborator of Salvador Allende (1908-1973) who was among the founder members of the, Chilean Socialist Party in 1933. Elected leader of the Left wing Coalition government in 1970,, Allende was assassinated in 1973 and his government was overthrown by the armed forces. So,, in a sense the man in the poem is Neruda himself, a revolutionary who went into exile and, returned to his homeland to be recognized in death as a great literary and political figure., Inspite of all these linkages, a poem can still have multiple meanings. So it is with this, poem. However, the foregoing comments will surely help you in reading this beautifully simple, but meaningful poem., , 22

Page 23 :

The Portrait in the Rock, Oh yes I knew him, I spent years with him,, with his golden and stony substance,, he was a man who was tired –, in Paraguay he left his father and mother,, his sons, his nephews,, , 5, , his latest in-laws,, his house, his chickens,, and some half-opened books., They called him to the door., When he opened it, the police took him,, , 10, , and they beat him up so much, that he spat blood in France, in Denmark,, in Spain, in Italy, moving about,, and so he died and I stopped seeing his face,, stopped hearing his profound silence;, , 15, , then once on a night of storms,, with snow spreading, a smooth cloak on the mountains,, on horseback, there, far off,, I looked and there was my friend –, , 20, , his face was formed in stone,, his profile defied the wild weather,, in his nose the wind was muffling, the moaning of the persecuted., There the exile came to ground., , 25, , Changed into stone, he lives in his own country., Annotations :, 1. I: the narrator. Who is the narrator ? Is it the poet himself or a persona invented by the poet., 2. golden and stony substance : inner strength, courage of conviction, , 23

Page 24 :

8. half-opened books : indicative of the suddenness of his departure ; his being caught, unawares and taken away by the police., 12. spat blood in France, in Denmark etc. : After being tortured by police, he probably escaped, to Europe but was always on the run and in poor health., 19. on horse back : the narrator is on horseback, riding through the mountains covered with, snow, on a stormy night. He imagines that he sees his friend’s face formed on the stone., 22. his profile defied the wild weather : The friend’s face holds out against the roughness of the, weather., 25. came to ground : to his final resting place., , The poem has to be seen basically from two points of view. The first is the very obvious, awareness that stone has been a medium of artistic expression from time immemorial., , All over, , the world, in India, Egypt and various other places, native races many centuries ago created stone, sculptures which still exist. In Chile itself, there is Easter Island, 2300 miles west of the, mainland. Here, on the last pacific dot of lava settled by Polynesians, Neruda had, a decade, after publishing The Stones of Chile meditated on the giant figures for which the place is, famous, “The stone larvae of mystery erected by an ancient culture”, now shattered by asphalt, and jet airliners. It was native figures that had raised the stone figures in a spirit of co-operation,, creativity and religious awe. This spirit has something in common with the creators of the, Sphinx in Egypt. In the USA giant portraits of American Presidents are carved on huge rocks at, Mount Rushmore. Perhaps the sight of mountains and rocks inspired Neruda to see the link, between nature and human aspiration, efforts and destiny., The second angle is that of nature. The Natural setting of statues provides a sense of, hope that the spirit of revolution continues to live, long after the actors (here, the Revolutionary, friend of the Poet) are dead and gone., When a poem turns philosophical, it raises certain questions in the mind. For instance,, who is the narrator ? Is it the poet or is it someone else ? Also, is the poem a celebration of the, life of a revolutionary ? Think about these questions., Questions and Answers, Q.1 Briefly sketch the life of the revolutionary., A., , The revolutionary was a common citizen, a victim of dictators and their political, repression. Like other spirited citizens be resisted and suffered. Like everyone else, he, 24

Page 25 :

had an extended family, a house, his possessions and his books. Books are indication that, the man was ideologically aware and informed. But a police crackdown is all it needs to, shatter his life. Once caught he is tortured. He escapes to Europe, falls sick and dies. The, poet hears no more about him till he imagines seeing his portrait on a Rock., , Q2. Why does the revolutionary spit blood in other countries?, A., , The revolutionary was hounded out and physically tortured. On the run, he spat blood in, various countries where he took shelter., , Q3. The poet sees the portrait on the rock ? Is he a visionary?, A., , He is a visionary because he imagines that the spirit of revolution transcends individual, death. His optimism about the value of revolution and protest is expressed in the sense of, permanence conveyed by stone., , Q4. Explain the image of the portrait on the rock ? Is revolution at one with nature?, A., , The portrait tries to reaffirm the superiority of the spirit of revolution over nature. In a, sense it transcends nature, the portrait holding out against the wild wind. The obvious, suggestion is that the, , revolutionary spirit, , embodied in the, , portrait lives, , transcends the vagaries of nature. A revolutionary dies, but revolution lives on., , 25, , on and