Page 3 :

Pearson Education Limited, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world, Visit us on the World Wide Web at: www.pearsoned.co.uk, © Pearson Education Limited 2014, All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without either the, prior written permission of the publisher or a licence permitting restricted copying in the United Kingdom, issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS., All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. The use of any trademark, in this text does not vest in the author or publisher any trademark ownership rights in such, trademarks, nor does the use of such trademarks imply any affiliation with or endorsement of this, book by such owners., , ISBN 10: 1-292-02726-6, ISBN 10: 1-269-37450-8, ISBN 13: 978-1-292-02726-5, ISBN 13: 978-1-269-37450-7, , British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data, A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library, Printed in the United States of America

Page 6 :

THE 8051, MICROCONTROLLERS, , OBJECTIVES, Upon completion of this chapter, you will be able to:, Compare and contrast microprocessors and microcontrollers., Describe the advantages of microcontrollers for some applications., Explain the concept of embedded systems., Discuss criteria for considering a microcontroller., Explain the variations of speed, packaging, memory, and, cost per unit and how these affect choosing a microcontroller., Compare and contrast the various members of the 8051 family., Compare 8051 microcontrollers offered by various manufacturers., , From Chapter 1 of The 8051 Microcontroller: A Systems Approach, First Edition. Muhammad Ali Mazidi, Janice, Gillispie Mazidi, Rolin D. McKinlay. Copyright © 2013 by Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved., , 1

Page 7 :

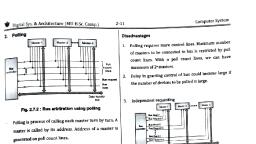

This chapter begins with a discussion of the role and importance of, microcontrollers in everyday life. In Section 1, we discuss criteria to consider in choosing a microcontroller, as well as the use of microcontrollers in, the embedded market. Section 2 covers various members of the 8051 family,, such as the 8052 and 8031, and their features. In addition, we discuss various, versions of the 8051 such as the 8751, AT89C51, and DS5000., , 1: MICROCONTROLLERS AND, EMBEDDED PROCESSORS, In this section, we discuss the need for microcontrollers and contrast them, with general-purpose microprocessors such as the Pentium and other x86 microprocessors. We also look at the role of microcontrollers in the embedded market., In addition, we provide some criteria on how to choose a microcontroller., , Microcontroller versus general-purpose microprocessor, What is the difference between a microprocessor and microcontroller?, By microprocessor is meant the general-purpose microprocessors such as, Intel’s x86 family (8086, 80286, 80386, 80486, and the Pentium) or Motorola’s, 680x0 family (68000, 68010, 68020, 68030, 68040, etc.). These microprocessors contain no RAM, no ROM, and no I/O ports on the chip itself. For this, reason, they are commonly referred to as general-purpose microprocessors. See, Figure 1., A system designer using a general-purpose microprocessor such as the, Pentium or the 68040 must add RAM, ROM, I/O ports, and timers externally to make them functional. Although the addition of external RAM, ROM,, and I/O ports makes these systems bulkier and much more expensive, they have, the advantage of versatility such that the designer can decide on the amount, of RAM, ROM, and I/O ports needed to fit the task at hand. This is not the, case with microcontrollers. A microcontroller has a CPU (a microprocessor), in addition to a fixed amount of RAM, ROM, I/O ports, and a timer all on a, single chip. In other words, the processor, RAM, ROM, I/O ports, and timer, are all embedded together on one chip; therefore, the designer cannot add any, Data bus, , CPU, , RAM, , CPU, , ROM, , I/O, port, , Timer, , Serial, COM, port, , I/O, , RAM, , ROM, , Timer Serial, COM, port, , Address bus, (a), , (b), , Figure 1. General-Purpose Microprocessor (a) System Contrasted With Microcontroller (b) System, , 2, , THE 8051 MICROCONTROLLERS

Page 8 :

Home, Appliances, Intercom, Telephones, Security systems, Garage door openers, Answering machines, Fax machines, Home computers, TVs, Cable TV tuner, VCR, Camcorder, Remote controls, Video games, Cellular phones, Musical instruments, Sewing machines, Lighting control, Paging, Camera, Pinball machines, Toys, Exercise equipment, , Office, Telephones, Computers, Security systems, Fax machine, Microwave, Copier, Laser printer, Color printer, Paging, , Auto, Trip computer, Engine control, Air bag, ABS, Instrumentation, Security system, Transmission control, Entertainment, Climate control, Cellular phone, Keyless entry, , Table 1. Some, Embedded Products, Using Microcontrollers, , external memory, I/O, or timer to it. The fixed amount of, on-chip ROM, RAM, and number of I/O ports in microcontrollers makes them ideal for many applications in which cost, and space are critical. In many applications, for example a TV, remote control, there is no need for the computing power of a, 486 or even an 8086 microprocessor because the space it takes,, the power it consumes, and the price per unit are much more, critical considerations than the computing power. These applications most often require some I/O operations to read signals, and turn on and off certain bits. For this reason some call these, processors IBP, “itty-bitty processors” (see “Good Things in, Small Packages Are Generating Big Product Opportunities,”, by Rick Grehan, BYTE magazine, September 1994; www.byte., com, for an excellent discussion of microcontrollers)., It is interesting to note that some microcontroller manufacturers have gone as far as integrating an ADC (analog-todigital converter) and other peripherals into the microcontroller., , Microcontrollers for embedded systems, In the literature discussing microprocessors, we often, see the term embedded system. Microprocessors and microcontrollers are widely used in embedded system products. An, embedded product uses a microprocessor (or microcontroller), to do one task and one task only. A printer is an example of, embedded system since the processor inside it performs only, one task—namely, getting the data and printing it. Contrast, this with a Pentium-based PC (or any x86 IBM-compatible PC)., A PC can be used for any number of applications such as word, processor, print server, bank teller terminal, video game player,, network server, or internet terminal. Software for a variety of, applications can be loaded and run. Of course the reason a PC, can perform myriad tasks is that it has RAM memory and an, operating system that loads the application software into RAM, and lets the CPU run it. In an embedded system, there is only, one application software that is typically burned into ROM. The, x86 PC contains or is connected to various embedded products, such as the keyboard, printer, modem, disk controller, sound, card, CD-ROM driver, or mouse. Each one of these peripherals has a microcontroller inside it that performs only one task., For example, inside every mouse there is a microcontroller that, performs the task of finding the mouse position and sending it, to the PC. Table 1 lists some embedded products., , x86 PC embedded applications, Although microcontrollers are the preferred choice for, many embedded systems, there are times that a microcontroller, THE 8051 MICROCONTROLLERS, , 3

Page 9 :

is inadequate for the task. For this reason, in recent years many manufacturers, of general-purpose microprocessors such as Intel, Freescale Semiconductor, Inc. (formerly Motorola), and AMD (Advanced Micro Devices, Inc.) have, targeted their microprocessor for the high end of the embedded market. While, Intel and AMD push their x86 processors for both the embedded and desktop, PC markets, Freescale has updated the 68000 family in the form of Coldfire to, be used mainly for the high end of embedded systems now that Apple no longer uses the 680x0 in their Macintosh. Since the early 1990s, a new processor, called ARM has been used in many embedded systems. Currently the ARM is, the most widely used microcontroller in the world and is targeted for the high, end of the embedded market as well as the PC and tablet market. It must be, noted that when a company targets a general-purpose microprocessor for the, embedded market, it optimizes the processor used for embedded systems. For, this reason, these processors are often called high-end embedded processors., Very often the terms embedded processor and microcontroller are used interchangeably., One of the most critical needs of an embedded system is to decrease, power consumption and space. This can be achieved by integrating more functions into the CPU chip. All the embedded processors based on the x86 and, 680x0 have low power consumption in addition to some forms of I/O, COM, port, and ROM all on a single chip. In high-performance embedded processors, the trend is to integrate more and more functions on the CPU chip and, let the designer decide which features he or she wants to use. This trend is, invading PC system design as well. Normally, in designing the PC motherboard we need a CPU plus a chip-set containing I/O, a cache controller, a flash, ROM containing BIOS, and finally a secondary cache memory. New designs, are emerging in industry. For example, Cyrix has announced that it is working, on a chip that contains the entire PC, except for DRAM. In other words, we, are about to see an entire computer on a chip., Currently, because of MS-DOS and Windows standardization many, embedded systems are using x86 PCs. In many cases, using the x86 PCs for, the high-end embedded applications not only saves money but also shortens, development time since there is a vast library of software already written for, the DOS and Windows platforms. The fact that Windows is a widely used and, well understood platform means that developing a Windows-based embedded, product reduces the cost and shortens the development time considerably., , Choosing a microcontroller, There are four major 8-bit microcontrollers. They are: Freescale’s 6811,, Intel’s 8051, Zilog’s Z8, and PIC 16X from Microchip Technology. Each of, these microcontrollers has a unique instruction set and register set; therefore,, they are not compatible with each other. Programs written for one will not run, on the others. There are also 16-bit and 32-bit microcontrollers made by various, chip makers. With all these different microcontrollers, what criteria do designers consider in choosing one? Three criteria in choosing microcontrollers are, as follows: (1) meeting the computing needs of the task at hand efficiently and, cost-effectively, (2) availability of software development tools such as compilers,, , 4, , THE 8051 MICROCONTROLLERS

Page 10 :

assemblers, and debuggers, and (3) wide availability and reliable sources of the, microcontroller. Next, we elaborate further on each of the above criteria., , Criteria for choosing a microcontroller, 1. The first and foremost criterion in choosing a microcontroller is that it, must meet the task at hand efficiently and cost-effectively. In analyzing the, needs of a microcontroller-based project, we must first see whether an 8-bit,, 16-bit, or 32-bit microcontroller can best handle the computing needs of the, task most effectively. Among other considerations in this category are:, (a) Speed. What is the highest speed that the microcontroller supports?, (b) Packaging. Does it come in a 40-pin DIP (dual inline package) or a QFP, (quad flat package), or some other packaging format? This is important, in terms of space, assembling, and prototyping the end product., (c) Power consumption. This is especially critical for battery-powered, products., (d) The amount of RAM and ROM on chip., (e) The number of I/O pins and the timer on the chip., (f) How easy it is to upgrade to higher-performance or lower powerconsumption versions., (g) Cost per unit. This is important in terms of the final cost of the product in, which a microcontroller is used. For example, there are microcontrollers, that cost 50 cents per unit when purchased 100,000 units at a time., 2. The second criterion in choosing a microcontroller is how easy it is to, develop products around it. Key considerations include the availability of an, assembler, debugger, a code-efficient C language compiler, emulator, technical support, and both in-house and outside expertise. In many cases, thirdparty vendor (i.e., a supplier other than the chip manufacturer) support for, the chip is as good as, if not better than, support from the chip manufacturer., 3. The third criterion in choosing a microcontroller is its ready availability in, needed quantities both now and in the future. For some designers, this is, even more important than the first two criteria. Currently, of the leading, 8-bit microcontrollers, the 8051 family has the largest number of diversified (multiple source) suppliers. By supplier is meant a producer besides, the originator of the microcontroller. In the case of the, Table 2. Some of the Companies Producing a Member, 8051, which was originated, of the 8051 Family, by Intel, several companies, Company, Website, also currently produce (or, have produced in the past) the, Intel, www.intel.com/design/mcs51, 8051. These companies include, Atmel, www.atmel.com, Intel, Atmel, Philips/Signetics,, Philips/Signetics, www.semiconductors.philips.com SiLab, Infineon (formerly, Siemens), Matra, and Dallas, Infineon, www.infineon.com, Semiconductor. See Table 2., Dallas Semi/Maxim www.maxim-ic.com, It should be noted, Silicon Labs, www.silabs.com, that Freescale, Zilog, and, THE 8051 MICROCONTROLLERS, , 5

Page 11 :

Microchip Technology have all dedicated massive resources to ensure wide, and timely availability of their product since their product is stable, mature,, and single sourced. In recent years, they also have begun to sell the ASIC, (application-specific integrated circuit) library cell of the microcontroller., , REvIEw QuESTIONS, 1. True or false. Microcontrollers are normally less expensive than microprocessors., 2. When comparing a system board based on a microcontroller and a generalpurpose microprocessor, which one is cheaper?, 3. A microcontroller normally has which of the following devices on-chip?, (a) RAM, (b) ROM, (c) I/O, (d) all of the above, 4. A general-purpose microprocessor normally needs which of the following, devices to be attached to it?, (a) RAM, (b) ROM, (c) I/O, (d) all of the above, 5. An embedded system is also called a dedicated system. Why?, 6. What does the term embedded system mean?, 7. Why does having multiple sources of a given product matter?, , 2: OvERvIEw OF THE 8051 FAMILY, In this section, we first look at the various members of the 8051 family, of microcontrollers and their internal features. In addition, we see who are the, different manufacturers of the 8051 and what kind of products they offer., , A brief history of the 8051, In 1981, Intel Corporation introduced an 8-bit microcontroller called the, 8051. This microcontroller had 128 bytes of RAM, 4K bytes of on-chip ROM,, two timers, one serial port, and four ports (each 8-bits wide) all on a single chip., At the time, it was also referred to as a “system on a chip.” The 8051 is an 8-bit, processor, meaning that the CPU can work on only 8 bits of data at a time. Data, larger than 8 bits has to be broken into 8-bit pieces to be processed by the CPU., The 8051 has a total of four I/O ports, each 8-bits wide. See Figure 2. Although, the 8051 can have a maximum of 64K bytes of on-chip ROM, many manufacturers have put only 4K bytes on the chip. This will be discussed in more detail later., The 8051 became widely popular after Intel allowed other manufacturers to make and market any flavors of the 8051 they please with the condition, that they remain code-compatible with the 8051. This has led to many versions, of the 8051 with different speeds and amounts of on-chip ROM marketed by, more than half a dozen manufacturers. Next, we review some of them. It is, important to note that although there are different flavors of the 8051 in terms, of speed and amount of on-chip ROM, they are all compatible with the original, 8051 as far as the instructions are concerned. This means that if you write your, program for one, it will run on any of them regardless of the manufacturer., , 6, , THE 8051 MICROCONTROLLERS

Page 12 :

External, interrupts, , On-chip, RAM, , Etc., Timer 0, Timer 1, , Bus, control, , Four I/O, ports, , Serial, port, , }, , Counter inputs, , Interrupt, control, , On-chip, ROM, for, program, code, , CPU, , OSC, , P0 P2, , P1 P3, , TXD, , RXD, , }, Address/Data, , Figure 2. Inside the 8051 Microcontroller Block Diagram, , 8051 microcontroller, The 8051 is the original member of the 8051 family. Intel refers to it as, MCS-51. Table 3 shows the main features of the 8051., , Other members of the 8051 family, There are two other members in the 8051 family of microcontrollers., They are the 8052 and the 8031., Table 3. Features of the 8051, Feature, , Quantity, , 8052 microcontroller, , ROM, RAM, Timer, I/O pins, Serial port, Interrupt sources, , 4K bytes, 128 bytes, 2, 32, 1, 6, , The 8052 is another member of the 8051 family., The 8052 has all the standard features of the 8051 as, well as an extra 128 bytes of RAM and an extra timer., In other words, the 8052 has 256 bytes of RAM and, three timers. It also has 8K bytes of on-chip program, ROM instead of 4K bytes., As can be seen from Table 4, the 8051 is a subset of the 8052; therefore, all programs written for the, 8051 will run on the 8052, but the reverse is not true., , Note: ROM amount indicates, on-chip program space., , THE 8051 MICROCONTROLLERS, , 7

Page 13 :

Table 4. Comparison of 8051 Family Members, Feature, , 8051, , ROM (on-chip program space in bytes) 4K, RAM (bytes), 128, Timers, 2, I/O pins, 32, Serial port, 1, Interrupt sources, 6, , 8052, , 8031, , 8K, 256, 3, 32, 1, 8, , 0K, 128, 2, 32, 1, 6, , 8031 microcontroller, Another member of the 8051 family is the 8031 chip. This chip is often, referred to as a ROM-less 8051 since it has 0K bytes of on-chip ROM. To, use this chip, you must add external ROM to it. This external ROM must, contain the program that the 8031 will fetch and execute. Contrast that to, the 8051 in which the on-chip ROM contains the program to be fetched and, executed but is limited to only 4K bytes of code. The ROM containing the, program attached to the 8031 can be as large as 64K bytes. In the process of, adding external ROM to the 8031, you lose two ports. That leaves only two, ports (of the four ports) for I/O operations. To solve this problem, you can, add external I/O to the 8031. There are also various speed versions of the 8031, available from different companies., , various 8051 microcontrollers, Although the 8051 is the most popular member of the 8051 family, you, will not see “8051” in the part number. This is because the 8051 is available, in different memory types, such as UV-EPROM, Flash, and NV-RAM, all of, which have different part numbers. The UV-EPROM version of the 8051 is the, 8751. The flash ROM version is marketed by many companies including Atmel, Corp. and Dallas Semiconductor. The Atmel Flash 8051 is called AT89C51,, while Dallas Semiconductor calls theirs DS89C4x0 (DS89C430/440/450)., The NV-RAM version of the 8051 made by Dallas Semiconductor is called, DS5000. There is also an OTP (one-time programmable) version of the 8051, made by various manufacturers. Next, we discuss briefly each of these chips, and their applications., 8751 microcontroller, , This 8751 chip has only 4K bytes of on-chip UV-EPROM. Using, this chip for development requires access to a PROM burner, as well as a, UV-EPROM eraser to erase the contents of UV-EPROM inside the 8751 chip, before you can program it again. Because the on-chip ROM for the 8751 is, UV-EPROM, it takes around 20 minutes to erase the 8751 before it can be, , 8, , THE 8051 MICROCONTROLLERS

Page 14 :

programmed again. This has led many manufacturers to introduce flash and, NV-RAM versions of the 8051, as we will discuss next. There are also various, speed versions of the 8751 available from different companies., DS89C4x0 from Dallas Semiconductor (Maxim), , Many popular 8051 chips have on-chip ROM in the form of flash memory. The AT89C51 from Atmel Corp. is one example of an 8051 with flash, ROM. This is ideal for fast development since flash memory can be erased, in seconds compared to the 20 minutes or more needed for the 8751. For this, reason, the AT89C51 is used in place of the 8751 to eliminate the waiting time, needed to erase the chip and thereby speed up the development time. Using the, AT89C51 to develop a microcontroller-based system requires a ROM burner, that supports flash memory; however, a ROM eraser is not needed. Notice that, in flash memory you must erase the entire contents of ROM in order to program it again. This erasing of flash is done by the PROM burner itself, which, is why a separate eraser is not needed. To eliminate the need for a PROM, burner, Dallas Semiconductor, now part of the Maxim Corp., has a version of, the 8051/52 called DS89C4x0 (DS89C430/...) that can be programmed via the, serial COM port of the x86 PC., Notice that the on-chip ROM for the DS89C4x0 is in the form of flash., The DS89C4x0 (430/440/450) comes with an on-chip loader, which allows the, program to be loaded into the on-chip flash ROM while it is in the system. This, can be done via the serial COM port of the x86 PC. This in-system program, loading of the DS89C4x0 via a PC serial COM port makes it an ideal home, development system. Dallas Semiconductor also has an NV-RAM version of, the 8051 called DS5000. The advantage of NV-RAM is the ability to change, the ROM contents one byte at a time. The DS5000 also comes with a loader,, allowing it to be programmed via the PC’s COM port. From Table 5, notice, that the DS89C4x0 is really an 8052 chip since it has 256 bytes of RAM and, three timers., DS89C4x0 Trainer, , The MDE8051 Trainer is available from www.MicroDigitalEd.com., , Table 5: Versions of 8051/52 Microcontroller From Dallas Semiconductor (Maxim), Part No., DS89C30, DS89C440, DS89C450, DS5000, DS80C320, DS87520, , ROM, , RAM, , I/O pins, , 16K (Flash), 32K (Flash), 64K (Flash), 8K (NV-RAM), 0K, 16K (UVROM), , 256, 256, 256, 128, 256, 256, , 32, 32, 32, 32, 32, 32, , Timers Interrupts Vcc, 3, 3, 3, 2, 3, 3, , 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, 6, , 5V, 5V, 5V, 5V, 5V, 5V, , Source: www.maxim-ic.com/products/microcontrollers/8051_drop_in.cfm, , THE 8051 MICROCONTROLLERS, , 9

Page 15 :

Table 6. Versions of 8051 From Atmel (All ROM Flash), Part No., AT89C51, AT89LV51, AT89C1051, AT89C2051, AT89C52, AT89LV52, , ROM, , RAM, , I/O Pins, , Timer, , Interrupt, , Vcc, , Packaging, , 4K, 4K, 1K, 2K, 8K, 8K, , 128, 128, 64, 128, 128, 128, , 32, 32, 15, 15, 32, 32, , 2, 2, 1, 2, 3, 3, , 6, 6, 3, 6, 8, 8, , 5V, 3V, 3V, 3V, 5V, 3V, , 40, 40, 20, 20, 40, 40, , Note: “C” in the part number indicates CMOS., , Table 7. Various Speeds of 8051 From Atmel, Part No., , Speed, , Pins, , AT89C51-12PC, AT89C51-16PC, AT89C51-20PC, , 12 MHz 40, 16 MHz 40, 20 MHz 40, , Packaging, , Use, , DIP plastic, DIP plastic, DIP plastic, , Commercial, Commercial, Commercial, , This Trainer allows you to program the DS89C4x0 chip from the COM port of, the x86 PC, with no need for a ROM burner., AT89C51 from Atmel Corporation, The Atmel Corp. has a wide selection of 8051 chips, as shown in Tables 6, and 7. For example, the AT89C51 is a popular and inexpensive chip used in many, small projects. It has 4K bytes of flash ROM. Notice the AT89C51-12PC, where, “C” before the 51 stands for CMOS, which has a low power consumption, “12”, indicates 12 MHz, “P” is for plastic DIP package, and “C” is for commercial., OTP version of the 8051, There are also OTP (one-time programmable) versions of the 8051, available from different sources. Flash and NV-RAM versions are typically, used for product development. When a product is designed and absolutely, finalized, the OTP version of the 8051 is used for mass production since it is, much cheaper in terms of price per unit., , 8051 family from Philips, Another major producer of the 8051 family is Philips Corporation., Indeed, it has one of the largest selections of 8051 microcontrollers. Many of, its products include features such as A-to-D converters, D-to-A converters,, extended I/O, and both OTP and flash., , 10, , THE 8051 MICROCONTROLLERS

Page 16 :

Table 8. The 8051 Chips From Silicon Labs, Part No., , Flash, , RAM, , Pins, , Packaging, , C8051F000, C8051F020, C8051F350, , 32K, 64K, 8K, , 256, 4352, 768, , 64, 100, 32, , TQFP, TQFP, TQFP, , Source: www.SiLabs.com, , 8051 family from SiLabs, Another major producer of the 8051 family is Silicon Labs Corporation., Indeed, it has become one of the largest producers of 8051 microcontrollers., Many of its products include features such as A-to-D converters, D-to-A, converters, extended I/O, PWM, I2C, and SPI. See Table 8., , REvIEw QuESTIONS, 1. Name three features of the 8051., 2. What is the major difference between the 8051 and 8052 microcontrollers?, 3. Give the size of RAM in each of the following., (a) 8051 (b) 8052, (c) 8031, 4. Give the size of the on-chip ROM in each of the following., (a) 8051 (b) 8052, (c) 8031, 5. The 8051 is a(n) _______-bit microprocessor., 6. State a major difference between the 8751, the AT89C51, and the, DS89C430., 7. True or false. The DS89C430 is really an 8052 chip., 8. True or false. The DS89C430 has a loader embedded to the chip, eliminating, the need for ROM burner., 9. The DS89C430 chip has _______ bytes of on-chip ROM., 10. The DS89C430 chip has _______ bytes of RAM., , SuMMARY, This chapter discussed the role and importance of microcontrollers in, everyday life. Microprocessors and microcontrollers were contrasted and compared. We discussed the use of microcontrollers in the embedded market. We, also discussed criteria to consider in choosing a microcontroller such as speed,, memory, I/O, packaging, and cost per unit. It also provided an overview of the, various members of the 8051 family of microcontrollers, such as the 8052 and, 8031, and their features. In addition, we discussed various versions of the 8051,, such as the AT89C51 and DS89C4x0, which are marketed by suppliers other, than Intel., THE 8051 MICROCONTROLLERS, , 11

Page 17 :

RECOMMENDED wEB LINKS, For a DS89C4x0-based Trainer, see www.MicroDigitalEd.com. For a, SiLabs trainer tutorial, see www.MicroDigitalEd.com., See the following websites for 8051 products and their features from, various companies:, • www.8052.com/chips.phtml, • www.MicroDigitalEd.com, , PROBLEMS, 1: MICROCONTROLLERS AND EMBEDDED PROCESSORS, 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., , True or False. A general-purpose microprocessor has on-chip ROM., True or False. A microcontroller has on-chip ROM., True or False. A microcontroller has on-chip I/O ports., True or False. A microcontroller has a fixed amount of RAM on the chip., What components are normally put together with the microcontroller into, a single chip?, 6. Intel’s Pentium chips used in Windows PCs need external ______ and, _____ chips to store data and code., 7. List three embedded products attached to a PC., 8. Why would someone want to use an x86 as an embedded processor?, 9. Give the name and the manufacturer of some of the most widely used 8-bit, microcontrollers., 10. In Question 9, which microcontroller has the most manufacture sources?, 11. In a battery-based embedded product, what is the most important factor, in choosing a microcontroller?, 12. In an embedded controller with on-chip ROM, why does the size of the, ROM matter?, 13. In choosing a microcontroller, how important is it to have multiple sources, for that chip?, 14. What does the term third-party support mean?, 15. If a microcontroller architecture has both 8-bit and 16-bit versions, which, of the following statements is true?, (a) The 8-bit software will run on the 16-bit system., (b) The 16-bit software will run on the 8-bit system., 2: OVERVIEW OF THE 8051 FAMILY, 16. The 8751 has _____ bytes of on-chip ROM., 17. The AT89C51 has _____ bytes of on-chip RAM., 18. The 8051 has ___ on-chip timer(s)., 19. The 8052 has ____bytes of on-chip RAM., , 12, , THE 8051 MICROCONTROLLERS

Page 18 :

20. The ROM-less version of the 8051 uses _____ as the part number., 21. The 8051 family has ____ pins for I/O., 22. The 8051 family has circuitry to support _____ serial ports., 23. The 8751 on-chip ROM is of type ______., 24. The AT89C51 on-chip ROM is of type _____., 25. The DS5000 on-chip ROM is of type _____., 26. The DS89C430 on-chip ROM is of type _____., 27. Give the amount of ROM and RAM for the following chips., (a) AT89C51, (b) DS89C430, (c) DS89C440, 28. Of the 8051 family, which memory type is the most cost-effective if you are, using a million of them in an embedded product?, 29. What is the difference between the 8031 and 8051?, 30. Of the 8051 microcontrollers, which one is the best for a home development environment? (You do not have access to a ROM burner.), , ANSwERS TO REvIEw QuESTIONS, 1: MICROCONTROLLERS AND EMBEDDED PROCESSORS, 1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., , True, A microcontroller-based system, (d), (d), It is dedicated to doing one type of job., Embedded system means that the application and processor are combined into a single, system., Having multiple sources for a given part means you are not hostage to one supplier. More, importantly, competition among suppliers brings about lower cost for that product., , 2: OVERVIEW OF THE 8051 FAMILY, 1. 128 bytes of RAM, 4K bytes of on-chip ROM, four 8-bit I/O ports., 2. The 8052 has everything that the 8051 has, plus an extra timer, and the on-chip ROM is, 8K bytes instead of 4K bytes. The RAM in the 8052 is 256 bytes instead of 128 bytes., 3. Both the 8051 and the 8031 have 128 bytes of RAM and the 8052 has 256 bytes., 4. (a) 4K bytes, (b) 8K bytes, (c) 0K bytes, 5. 8, 6. The main difference is the type of on-chip ROM. In the 8751, it is UV-EPROM; in the, AT89C51, it is flash; and in the DS89C430, it is flash with a loader on the chip., 7. True, 8. True, 9. 16K, 10. 256, , THE 8051 MICROCONTROLLERS, , 13

Page 19 :

This page intentionally left blank

Page 20 :

8051 ASSEMBLY, LANGUAGE, PROGRAMMING, , OBJECTIVES, Upon completion of this chapter, you will be able to:, List the registers of the 8051 microcontroller., Manipulate data using the registers and MOV instructions., Code simple 8051 Assembly language instructions., Assemble and run an 8051 program., Describe the sequence of events that occur upon 8051 power-up., Examine programs in ROM code of the 8051., Explain the ROM memory map of the 8051., Detail the execution of 8051 Assembly language instructions., Describe 8051 data types., Explain the purpose of the PSW (program status word) register., Discuss RAM memory space allocation in the 8051., Diagram the use of the stack in the 8051., Manipulate the register banks of the 8051., Understand the RISC and CISC architectures., From Chapter 2 of The 8051 Microcontroller: A Systems Approach, First Edition. Muhammad Ali Mazidi, Janice, Gillispie Mazidi, Rolin D. McKinlay. Copyright © 2013 by Pearson Education, Inc. All rights reserved., , 15

Page 21 :

In Section 1, we look at the inside of the 8051. We demonstrate some, of the widely used registers of the 8051 with simple instructions such as MOV, and ADD. In Section 2, we examine Assembly language and machine language, programming and define terms such as mnemonics, opcode, and operand. The, process of assembling and creating a ready-to-run program for the 8051 is discussed in Section 3. Step-by-step execution of an 8051 program and the role of, the program counter are examined in Section 4. In Section 5, we look at some, widely used Assembly language directives, pseudocode, and data types related, to the 8051. In Section 6, we discuss the flag bits and how they are affected by, arithmetic instructions. Allocation of RAM memory inside the 8051 plus the, stack and register banks of the 8051 are discussed in Section 7. Section 8 examines the concepts of RISC and CISC architectures., , 1: INSIDE THE 8051, In this section, we examine the major registers of the 8051 and show, their use with the simple instructions MOV and ADD., , Registers, , D7, , D6, , D5, , D4, , D3, , D2, , D1, , D0, , In the CPU, registers, are used to store information temporarily. That information could be a byte of data to be processed, or, an address pointing to the data to be fetched. The vast majority of 8051 registers are 8-bit registers. In the 8051, there is only one data type: 8 bits. The 8 bits, of a register are shown in the diagram from the MSB (most significant bit) D7, to the LSB (least significant bit) D0. With an 8-bit data type, any data larger, than 8 bits must be broken into 8-bit chunks before, it is processed. Since there are a large number of, A, registers in the 8051, we will concentrate on some, of the widely used general-purpose registers., B, The most widely used registers of the 8051 are, R0, A (accumulator), B, R0, R1, R2, R3, R4, R5, R6, R7,, DPTR (data pointer), and PC (program counter). All, R1, of the above registers are 8 bits, except DPTR and, R2, the program counter. See Figure 1(a) and (b)., R3, R4, R5, , DPTR, , R6, R7, , PC, , Figure 1(a). Some 8-bit, Registers of the 8051, , 16, , DPH, , DPL, , PC (program counter), , Figure 1(b). Some 8051 16-bit Registers, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING

Page 23 :

Notice in instruction “MOV R5,#0F9H” a 0 is used between the # and, F to indicate that F is a hex number and not a letter. In other words, “MOV, R5,#F9H” will cause an error., 2. If values 0 to F are moved into an 8-bit register, the rest of the bits are, assumed to be all zeros. For example, in “MOV A,#5” the result will be A, = 05: that is, A = 00000101 in binary., 3. Moving a value that is too large into a register will cause an error., MOV A,#7F2H ;ILLEGAL: 7F2H > 8 bits (FFH), MOV R2,#456 ;ILLEGAL: 456 > 255 decimal (FFH), 4. A value to be loaded into a register must be preceded with a pound sign, (#). Otherwise it means to load from a memory location. For example,, “MOV A,17H” means to move into A the value held in memory location, 17H, which could have any value. In order to load the value 17H into the, accumulator, we must write “MOV A,#17H” with the # preceding the, number. Notice that the absence of the pound sign will not cause an error, by the assembler since it is a valid instruction. However, the result would, not be what the programmer intended. This is a common error for beginning programmers in the 8051., , ADD instruction, The ADD instruction has the following format:, ADD A,source, ;ADD the source operand, ;to the accumulator, The ADD instruction tells the CPU to add the source byte to register, A and put the result in register A. To add two numbers such as 25H and 34H,, each can be moved to a register and then added together:, MOV A,#25H, MOV R2,#34H, ADD A,R2 , , , ;load 25H into A, ;load 34H into R2, ;add R2 to accumulator, ;(A = A + R2), , Executing the program above results in A = 59H (25H + 34H = 59H), and R2 = 34H. Notice that the content of R2 does not change. The program, above can be written in many ways, depending on the registers used. Another, way might be:, MOV R5,#25H, MOV R7,#34H, MOV A,#0 , ADD A,R5 , , ADD A,R7 , , , 18, , ;load 25H into R5 (R5=25H), ;load 34H into R7 (R7=34H), ;load 0 into A (A=0,clear A), ;add to A content of R5, ;where A = A + R5, ;add to A content of R7, ;where A = A + R7, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING

Page 24 :

The program above results in A = 59H. There are always many ways to, write the same program. One question that might come to mind after looking, at the program is whether it is necessary to move both data items into registers, before adding them together. The answer is no, it is not necessary. Look at the, following variation of the same program:, MOV A,#25H ;load one operand into A (A=25H), ADD A,#34H ;add the second operand 34H to A, In the above case, while one register contained one value, the second, value followed the instruction as an operand. This is called an immediate operand. The examples shown so far for the ADD instruction indicate that the, source operand can be either a register or immediate data, but the destination, must always be register A, the accumulator. In other words, an instruction such, as “ADD R2,#12H” is invalid since register A (accumulator) must be involved, in any arithmetic operation. Notice that “ADD R4,A” is also invalid for the reason that A must be the destination of any arithmetic operation. To put it simply:, In the 8051, register A must be involved and be the destination for all arithmetic, operations. The foregoing discussion explains why register A is referred to as the, accumulator., There are two 16-bit registers in the 8051: program counter and data, pointer. The importance and use of the program counter are covered in, Section 3. The DPTR register is used in accessing data., , Review Questions, 1. Write the instructions to move value 34H into register A and value 3FH, into register B, then add them together., 2. Write the instructions to add the values 16H and CDH. Place the result in, register R2., 3. True or false. No value can be moved directly into registers R0–R7., 4. What is the largest hex value that can be moved into an 8-bit register?, What is the decimal equivalent of the hex value?, 5. The vast majority of registers in 8051 are _____ bits., , 2: INTRODUCTION TO 8051 ASSEMBLY PROGRAMMING, In this section, we discuss Assembly language format and define some, widely used terminology associated with Assembly language programming., While the CPU can work only in binary, it can do so at a very high, speed. For humans, however, it is quite tedious and slow to deal with 0s and, 1s in order to program the computer. A program that consists of 0s and 1s, is called machine language. In the early days of the computer, programmers, coded programs in machine language. Although the hexadecimal system was, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING, , 19

Page 25 :

used as a more efficient way to represent binary numbers, the process of working in machine code was still cumbersome for humans. Eventually, Assembly, languages were developed that provided mnemonics for the machine code, instructions, plus other features that made programming faster and less prone, to error. The term mnemonic is frequently used in computer science and engineering literature to refer to codes and abbreviations that are relatively easy, to remember. Assembly language programs must be translated into machine, code by a program called an assembler. Assembly language is referred to as a, low-level language because it deals directly with the internal structure of the, CPU. To program in Assembly language, the programmer must know all the, registers of the CPU and the size of each, as well as other details., Today, one can use many different programming languages, such as, BASIC, Pascal, C, C++, Java, and numerous others. These languages are, called high-level languages because the programmer does not have to be concerned with the internal details of the CPU. Whereas an assembler is used to, translate an Assembly language program into machine code (sometimes also, called object code or opcode for operation code), high-level languages are, translated into machine code by a program called a compiler. For instance, to, write a program in C, one must use a C compiler to translate the program into, machine language. Now we look at 8051 Assembly language format and use, an 8051 assembler to create a ready-to-run program., , Structure of Assembly language, An Assembly language program consists of, among other things, a, series of lines of Assembly language instructions. An Assembly language, instruction consists of a mnemonic, optionally followed by one or two operands. The operands are the data items being manipulated, and the mnemonics, are the commands to the CPU, telling it what to do with those items., A given Assembly language program (see Program 1) is a series of, statements, or lines, which are either Assembly language instructions such as, , ORG 0H , MOV R5,#25H, MOV R7,#34H, MOV A,#0, ADD A,R5, , ADD A,R7, , ADD A,#12H, , HERE:SJMP HERE , END , , ;start (origin) at location 0, ;load 25H into R5, ;load 34H into R7, ;load 0 into A , ;add contents of R5 to A , ;now A = A + R5, ;add contents of R7 to A, ;now A = A + R7, ;add to A value 12H, ;now A = A + 12H, ;stay in this loop, ;end of asm source file, , Program 1. Sample of an Assembly Language Program, , 20, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING

Page 26 :

ADD and MOV, or statements called directives. While instructions tell the, CPU what to do, directives (also called pseudo-instructions) give directions to, the assembler. For example, in the above program while the MOV and ADD, instructions are commands to the CPU, ORG and END are directives to the, assembler. ORG tells the assembler to place the opcode at memory location, 0, while END indicates to the assembler the end of the source code. In other, words, one is for the start of the program and the other one for the end of, the program., An Assembly language instruction consists of four fields:, [label:], , mnemonic, , [operands], , [;comment], , Brackets indicate that a field is optional, and not all lines have them., Brackets should not be typed in. Regarding the above format, the following, points should be noted., 1. The label field allows the program to refer to a line of code by name., The label field cannot exceed a certain number of characters. Check your, assembler for the rule., 2. The Assembly language mnemonic (instruction) and operand(s) fields, together perform the real work of the program and accomplish the tasks for, which the program was written. In Assembly language statements such as, ADD A,B, MOV A,#67, ADD and MOV are the mnemonics, which produce opcodes; and “A, B”, and “A, #67” are the operands. Instead of a mnemonic and an operand,, these two fields could contain assembler pseudo-instructions, or directives., Remember that directives do not generate any machine code (opcode) and, are used only by the assembler, as opposed to instructions that are translated into machine code (opcode) for the CPU to execute. In Program 1,, the commands ORG (origin) and END are examples of directives (some, 8051 assemblers use .ORG and .END). Check your assembler for the rules., More of these pseudo-instructions are discussed in detail in Section 5., 3. The comment field begins with a semicolon comment indicator “;”., Comments may be at the end of a line or on a line by themselves. The, assembler ignores comments, but they are indispensable to programmers., Although comments are optional, it is recommended that they be used, to describe the program and make it easier for someone else to read and, understand, or for the programmer to remember what they wrote., 4. Notice the label “HERE” in the label field in Program 1. Any label referring to an instruction must be followed by a colon, “:”. In the SJMP (short, jump instruction), the 8051 is told to stay in this loop indefinitely. If your, system has a monitor program you do not need this line and it should be, deleted from your program. In the next section, we will see how to create, a ready-to-run program., 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING, , 21

Page 27 :

REVIEW QUESTIONS, 1. What is the purpose of pseudo-instructions?, 2. _____________ are translated by the assembler into machine code, whereas, __________________ are not., 3. True or false. Assembly language is a high-level language., 4. Which of the following produces opcode?, (a) ADD A,R2 (b) MOV A,#12 (c) ORG 2000H (d) SJMP HERE, 5. Pseudo-instructions are also called ___________., 6. True or false. Assembler directives are not used by the CPU itself. They are, simply a guide to the assembler., 7. In question 4, which one is an assembler directive?, , 3: ASSEMBLING AND RUNNING, AN 8051 PROGRAM, Now that the basic form of an Assembly language program has been, given, the next question is this: How it is created, assembled, and made ready to, run? The steps to create an executable Assembly, language program are outlined as follows. See, Figure 2., Editor, program, 1. First we use an editor to type in a program, myfile.asm, similar to Program 1. Many excellent editors, or word processors are available that can, be used to create and/or edit the program., Assembler, A widely used editor is the MS-DOS EDIT, program, program (or Notepad in Windows), which, comes with all Microsoft operating systems., myfile.lst, Notice that the editor must be able to promyfile.obj, other obj files, duce an ASCII file. For many assemblers,, the file names follow the usual DOS convenLinker, tions, but the source file has the extension, program, “asm” or “src”, depending on which assembler you are using. Check your assembler, for the convention. The “asm” extension for, myfile.abs, the source file is used by an assembler in the, next step., 2. The “asm” source file containing the proOH, gram code created in step 1 is fed to an, program, 8051 assembler. The assembler converts the, instructions into machine code. The assemmyfile.hex, bler will produce an object file and a list file., The extension for the object file is “obj” while, the extension for the list file is “lst”., Figure 2. Steps to Create a Program, , 22, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING

Page 28 :

1 0000, , ORG 0H , ;start (origin) at 0, 2 0000 7D25 , MOV R5,#25H, ;load 25H into R5, 3 0002 7F34 , MOV R7,#34H, ;load 34H into R7, 4 0004 7400 , MOV A,#0, ;load 0 into A , 5 0006 2D, , ADD A,R5, ;add contents of R5 to A, ;now A = A + R5, 6 0007 2F, ADD A,R7 , ;add contents of R7 to A, ;now A = A + R7, 7 0008 2412, ADD A,#12H, ;add to A value 12H, ;now A = A + 12H, 8 000A 80FE HERE:, SJMP HERE , ;stay in this loop, 9 000C , END , ;end of asm source file, Program 2. List File for Program 1, , 3. Assemblers require a third step called linking. The link program takes, one or more object files and produces an absolute object file with the, extension “abs”. This abs file is used by 8051 trainers that have a monitor program., 4. Next, the “abs” file is fed into a program called “OH” (object to hex, converter), which creates a file with extension “hex” that is ready to, burn into ROM. This program comes with all 8051 assemblers. Recent, Windows-based assemblers combine steps 2 through 4 into one step., , More about “asm” and “obj” files, The “asm” file is also called the source file and for this reason some, assemblers require that this file have the “src” extension. Check your 8051, assembler to see which extension it requires. As mentioned earlier, this file is, created with an editor such as DOS EDIT or Windows Notepad. The 8051, assembler converts the asm file’s Assembly language instructions into machine, language and provides the obj (object) file. In addition to creating the object, file, the assembler also produces the lst file (list file)., , lst file, The lst (list) file, which is optional, is very useful to the programmer, because it lists all the opcodes and addresses, as well as errors that the assembler detected. See Program 2. Many assemblers assume that the list file is, not wanted unless you indicate that you want to produce it. This file can be, accessed by an editor such as DOS EDIT and displayed on the monitor or sent, to the printer to produce a hard copy. The programmer uses the list file to find, syntax errors. It is only after fixing all the errors indicated in the lst file that the, obj file is ready to be input to the linker program., , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING, , 23

Page 29 :

Review Questions, 1. True or false. The DOS program EDIT produces an ASCII file., 2. True or false. Generally, the extension of the source file is “asm” or “src”., 3. Which of the following files can be produced by the DOS EDIT program?, (a) myprog.asm (b) myprog.obj (c) myprog.exe (d) myprog.lst, 4. Which of the following files is produced by an 8051 assembler?, (a) myprog.asm (b) myprog.obj (c) myprog.hex (d) myprog.lst, 5. Which of the following files lists syntax errors?, (a) myprog.asm (b) myprog.obj (c) myprog.hex (d) myprog.lst, , 4: THE PROGRAM COUNTER AND ROM, SPACE IN THE 8051, In this section, we examine the role of the program counter (PC) register, in executing an 8051 program. We also discuss ROM memory space for various 8051 family members., , Program counter in the 8051, Another important register in the 8051 is the program counter. The, program counter points to the address of the next instruction to be executed., As the CPU fetches the opcode from the program ROM, the program counter, is incremented to point to the next instruction. The program counter in the, 8051 is 16-bits wide. This means that the 8051 can access program addresses, 0000 to FFFFH, a total of 64K bytes of code. However, not all members of, the 8051 have the entire 64K bytes of on-chip ROM installed, as we will see, soon. Where does the 8051 wake up when it is powered? We will discuss this, important topic next., , Where the 8051 wakes up when it is powered up, One question that we must ask about any microcontroller (or microprocessor) is, At what address does the CPU wake up upon applying power, to it? Each microprocessor is different. In the case of the 8051 family (i.e., all, members regardless of the maker and variation), the microcontroller wakes, up at memory address 0000 when it is powered up. By powering up, we mean, applying Vcc to the RESET pin. In other words, when the 8051 is powered, up, the program counter has the value of 0000 in it. This means that it expects, the first opcode to be stored at ROM address 0000H. For this reason, in the, 8051 system, the first opcode must be burned into memory location 0000H, of program ROM since this is where it looks for the first instruction when it, is booted. We achieve this by the ORG statement in the source program as, shown earlier. Next, we discuss the step-by-step action of the program counter in fetching and executing a sample program., , 24, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING

Page 30 :

Placing code in program ROM, To get a better understanding of the role of the program counter in fetching, and executing a program, we examine the action of the program counter as each, instruction is fetched and executed. For example, consider the list file of Program 2, and how the code is placed in the ROM of an 8051 chip. As we can see, the opcode, and operand for each instruction are listed on the left side of the list file., After the program is burned into ROM of an 8051 family member, such, as 8751 or AT8951 or DS5000, the opcode and operand are placed in ROM, memory locations starting at 0000 as shown in the table below., ROM Address, , Machine Language, , Assembly Language, , 0000, 0002, 0004, 0006, 0007, 0008, 000A, , 7D25, 7F34, 7400, 2D, 2F, 2412, 80FE, , MOV R5,#25H, MOV R7,#34H, MOV A,#0, ADD A,R5, ADD A,R7, ADD A,#12H, HERE: SJMP HERE, , The table shows that address 0000 contains 7D, which is the opcode for, moving a value into register R5, and address 0001 contains the operand (in this case, 25H) to be moved to R5. Therefore, the instruction “MOV, R5,#25H” has a machine code of “7D25”, where 7D is the, Table 1. ROM Contents, opcode and 25 is the o, perand. Similarly, the machine code, Address, Code, “7F34” is located in memory locations 0002 and 0003 and, represents the opcode and the operand for the instruction, 0000 , 7D, “MOV R7,#34H”. In the same way, machine code “7400”, 0001 , 25, is located in memory locations 0004 and 0005 and repre0002 , 7F, sents the opcode and the operand for the instruction “MOV, 0003 , 34, A,#0”. The memory location 0006 has the opcode of 2D,, 0004 , 74, which is the opcode for the instruction “ADD A,R5” and, memory location 0007 has the content 2F, which is the, 0005 , 00, opcode for the “ADD A,R7” instruction. The opcode for, 0006 , 2D, the instruction “ADD A,#12H” is located at address 0008, 0007 , 2F, and the operand 12H at address 0009. The memory loca0008 , 24, tion 000A has the opcode for the SJMP instruction and its, target address is located in location 000B. Table 1 shows, 0009 , 12, the ROM contents., 000A , 80, 000B , FE, , Executing a program byte by byte, , Assuming that the above program is burned into the ROM of an 8051, chip (8751, AT8951, or DS5000), the following is a step-by-step description of, the action of the 8051 upon applying power to it., , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING, , 25

Page 31 :

1. When the 8051 is powered up, the program counter has 0000 and starts to, fetch the first opcode from location 0000 of the program ROM. In the case, of the above program the first opcode is 7D, which is the code for moving, an operand to R5. Upon executing the opcode, the CPU fetches the value, 25 and places it in R5. Now one instruction is finished. Then the program, counter is incremented to point to 0002 (PC = 0002), which contains, opcode 7F, the opcode for the instruction “MOV R7,..”., 2. Upon executing the opcode 7F, the value 34H is moved into R7. Then the, program counter is incremented to 0004., 3. ROM location 0004 has the opcode for the instruction “MOV A,#0”., This instruction is executed and now PC = 0006. Notice that all the above, instructions are 2-byte instructions; that is, each one takes two memory, locations., 4. Now PC = 0006 points to the next instruction, which is “ADD A,R5”. This, is a 1-byte instruction. After the execution of this instruction, PC = 0007., 5. The location 0007 has the opcode 2F, which belongs to the instruction, “ADD A,R7”. This also is a 1-byte instruction. Upon execution of this, instruction, PC is incremented to 0008. This process goes on until all the, instructions are fetched and executed. The fact that the program counter, points at the next instruction to be executed explains why some microprocessors (notably the x86) call the program counter the instruction, pointer., , ROM memory map in the 8051 family, Some family members have only 4K bytes of on-chip ROM (e.g.,, 8751, AT8951) and some, such as the AT89C52, have 8K bytes of ROM., Dallas Semiconductor’s DS5000-32 has 32K bytes of o n-chip ROM., Dallas Semiconductor also has an 8051 with 64K bytes of on-chip ROM., See Figure 3. The point to remember is that no member of the 8051 family can access more than 64K bytes of opcode since the program counter in the 8051 is a 16-bit register (0000 to FFFF address range). It, must be noted that while the first location of program ROM inside the, Example 1, Find the ROM memory address of each of the following 8051 chips:, (a) AT89C51 with 4KB (b) DS89C420 with 16KB (c) DS5000-32 with 32KB., Solution:, (a) With 4K bytes of on-chip ROM memory space, we have 4096 bytes (4 × 1024, = 4096). This maps to address locations of 0000 to 0FFFH. Notice that 0 is, always the first location. (b) With 16K bytes of on-chip ROM memory space,, we have 16,384 bytes (16 × 1024 = 16,384), which gives 0000–3FFFH. (c) With, 32K bytes we have 32,768 bytes (32 × 1024 = 32,768). Converting 32,768 to hex,, we get 8000H; therefore, the memory space is 0000 to 7FFFH., , 26, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING

Page 32 :

Byte, 0000, , Byte, , Byte, 0000, , 0000, , 0FFF, 8051, AT89C51, , 3FFF, DS89C420/30, , 7FFF, DS5000-32, Figure 3. 8051 On-Chip ROM Address Range, , 8051 has the address of 0000, the last location can be different depending on the size of the ROM on the chip. Among the 8051 family members,, the 8751 and AT8951 have 4K bytes of on-chip ROM. This 4K bytes of, ROM memory has memory addresses of 0000 to 0FFFH. Therefore, the, first location of on-chip ROM of this 8051 has an address of 0000 and the, last location has the address of 0FFFH. Look at Example 1 to see how this, is computed., , Review Questions, 1. In the 8051, the program counter is ______ bits wide., 2. True or false. Every member of the 8051 family, regardless of the maker,, wakes up at memory 0000H when it is powered up., 3. At what ROM location do we store the first opcode of an 8051 program?, 4. The instruction “MOV A,#44H” is a ____-byte instruction., 5. What is the ROM address space for the 8052 chip?, , 5: 8051 DATA TYPES AND DIRECTIVES, In this section, we look at some widely used data types and directives, supported by the 8051 assembler., , 8051 data type and directives, The 8051 microcontroller has only one data type. It is 8 bits, and the, size of each register is also 8 bits. It is the job of the programmer to break down, data larger than 8 bits (00 to FFH, or 0 to 255 in decimal) to be processed by, 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING, , 27

Page 33 :

the CPU. The data types used by the 8051 can be positive or, negative., , DB (define byte), The DB directive is the most widely used data directive in the assembler., It is used to define the 8-bit data. When DB is used to define data, the numbers, can be in decimal, binary, hex, or ASCII formats. For decimal, the “D” after the, decimal number is optional, but using “B” (binary) and “H” (hexadecimal) for, the others is required. Regardless of which is used, the assembler will convert, the numbers into hex. To indicate ASCII, simply place the characters in quotation marks (“like this”). The assembler will assign the ASCII code for the numbers or characters automatically. The DB directive is the only directive that can, be used to define ASCII strings larger than two characters; therefore, it should, be used for all ASCII data definitions. Following are some DB examples:, ORG, DATA1:, DB, DATA2:, DB, DATA3:, DB, , ORG, DATA4:, DB, ORG, DATA6:, DB, , 500H, 28, , 00110101B, , 39H, , 510H, “2591”, , 518H, “My name is Joe”, , ;DECIMAL(1C in hex), ;BINARY (35 in hex), ;HEX, ;ASCII NUMBERS, ;ASCII CHARACTERS, , Either single or double quotes can be used around ASCII strings. This, can be useful for strings, which contain a single quote such as “O’Leary”. DB, is also used to allocate memory in byte-sized chunks., , Assembler directives, The following are some more widely used directives of the 8051., ORG (origin), , The ORG directive is used to indicate the beginning of the address., The number that comes after ORG can be either in hex or in decimal. If the, number is not followed by H, it is decimal and the assembler will convert it to, hex. Some assemblers use “.ORG” (notice the dot) instead of “ORG” for the, origin directive. Check your assembler., EQU (equate), , This is used to define a constant without occupying a memory location. The EQU directive does not set aside storage for a data item but associates a constant value with a data label so that when the label appears in the, program, its constant value will be substituted for the label. The following, uses EQU for the counter constant and then the constant is used to load the, R3 register., , 28, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING

Page 34 :

COUNT, EQU 25, ... ...., MOV R3,#COUNT, When executing the instruction “MOV R3,#COUNT”, the register R3, will be loaded with the value 25 (notice the # sign). What is the advantage, of using EQU? Assume that there is a constant (a fixed value) used in many, different places in the program, and the programmer wants to change its value, throughout. By the use of EQU, the programmer can change it once and, the assembler will change all of its occurrences, rather than search the entire, program trying to find every occurrence., END directive, , Another important pseudocode is the END directive. This indicates to, the assembler the end of the source (asm) file. The END directive is the last line, of an 8051 program, meaning that in the source code anything after the END, directive is ignored by the assembler. Some assemblers use “.END” (notice the, dot) instead of “END”., , Rules for labels in Assembly language, By choosing label names that are meaningful, a programmer can, make a program much easier to read and maintain. There are several rules, that names must follow. First, each label name must be unique. The names, used for labels in Assembly language programming consist of alphabetic letters in both uppercase and lowercase, the digits 0 through 9, and the special, characters question mark (?), period (.), at (@), underline (_), and dollar sign, ($). The first character of the label must be an alphabetic character. In other, words it cannot be a number. Every assembler has some reserved words that, must not be used as labels in the program. Foremost among the reserved, words are the mnemonics for the instructions. For example, MOV and ADD, are reserved since they are instruction mnemonics. In addition to the mnemonics there are some other reserved words. Check your assembler for the, list of reserved words., , Review Questions, 1. The __________ directive is always used for ASCII strings., 2. How many bytes are used by the following?, DATA_1: DB “AMERICA”, 3. What is the advantage in using the EQU directive to define a constant value?, 4. How many bytes are set aside by each of the following directives?, (a) ASC_DATA: DB “1234” (b) MY_DATA: DB “ABC1234”, 5. State the contents of memory locations 200H–205H for the following:, ORG 200H, MYDATA:, DB, “ABC123”, 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING, , 29

Page 35 :

6: 8051 FLAG BITS AND THE PSW REGISTER, Like any other microprocessor, the 8051 has a flag register to indicate, arithmetic conditions such as the carry bit. The flag register in the 8051 is called, the program status word (PSW) register. In this section, we discuss various bits, of this register and provide some examples of how it is altered., , PSW (program status word) register, The PSW register is an 8-bit register. It is also referred to as the flag, register. Although the PSW register is 8 bits wide, only 6 bits of it are used, by the 8051. The two unused bits are user-definable flags. Four of the flags, are called conditional flags, meaning that they indicate some conditions that, result after an instruction is executed. These four are CY (carry), AC (auxiliary carry), P (parity), and OV (overflow)., As seen from Figure 4, the bits PSW.3 and PSW.4 are designated as, RS0 and RS1, respectively, and are used to change the bank registers. They are, explained in the next section. The PSW.5 and PSW.1 bits are general-purpose, status flag bits and can be used by the programmer for any purpose. In other, words, they are user definable., The following is a brief explanation of four of the flag bits of the PSW, register. The impact of instructions on these registers is then discussed., , AC, , CY, , F0, , RS1, , RS0, , OV, , --, , P, , CY, AC, F0, RS1, RS0, OV, -P, , PSW.7, PSW.6, PSW.5, PSW.4, PSW.3, PSW.2, PSW.1, PSW.0, , Carry flag, Auxiliary carry flag, Available to the user for general purpose, Register bank selector bit 1, Register bank selector bit 0, Overflow flag, User-definable bit, Parity flag. Set/cleared by hardware each instruction cycle, to indicate an odd/even number of 1 bits in the accumulator., , RS1, 0, 0, 1, 1, , RS0, 0, 1, 0, 1, , Register Bank, 0, 1, 2, 3, , Address, 00H–07H, 08H–0FH, 10H–17H, 18H–1FH, , Figure 4. Bits of the PSW Register, , 30, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING

Page 36 :

Table 2. Instructions That Affect, Flag Bits, Instruction, ADD, ADDC, SUBB, MUL, DIV, DA, RRC, RLC, SETB C, CLR C, CPL C, ANL C, bit, ANL C, /bit, ORL C, bit, ORL C, /bit, MOV C, bit, CJNE, , CY, the carry flag, , CY, , OV, , AC, , X, X, X, 0, 0, X, X, X, 1, 0, X, X, X, X, X, X, X, , X, X, X, X, X, , X, X, X, , This flag is set whenever there is a carry, out from the D7 bit. This flag bit is affected, after an 8-bit addition or subtraction. It can, also be set to 1 or 0 directly by an instruction, such as “SETB C” or “CLR C”, where “SETB, C” stands for “set bit carry” and “CLR C” for, “clear carry”., AC, the auxiliary carry flag, , If there is a carry from D3 to D4 during an ADD or SUB operation, this bit is set;, otherwise, it is cleared. This flag is used by, instructions that perform BCD (binary coded, decimal) arithmetic., P, the parity flag, , The parity flag reflects the number of 1s, in the A (accumulator) register only. If the A, register contains an odd number of 1s, then P, = 1. Therefore, P = 0 if A has an even number, of 1s., OV, the overflow flag, , Note: X can be 0 or 1., , This flag is set whenever the result of a, signed number operation is too large, causing, the high-order bit to overflow into the sign bit. In general, the carry flag is, used to detect errors in unsigned arithmetic operations. The overflow flag is, only used to detect errors in signed arithmetic operations. Table 2 lists the, instructions that affect flag bits., , ADD instruction and PSW, Next, we examine the impact of the ADD instruction on the flag bits, CY, AC, and P of the PSW register. Some examples should clarify their status., Although the flag bits affected by the ADD instruction are CY (carry flag), P, (parity flag), AC (auxiliary carry flag), and OV (overflow flag), we will focus, on flags CY, AC, and P for now., See Examples 2 through 4 for the impact on selected flag bits as a result, of the ADD instruction., , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING, , 31

Page 37 :

Example 2, Show the status of the CY, AC, and P flags after the addition of 38H and 2FH in, the following instructions., MOV A,#38H, ADD A,#2FH, ;after the addition A=67H, CY=0, Solution:, , , , , 38 , + 2F , 67 , , 00111000, 00101111, 01100111, , CY = 0 since there is no carry beyond the D7 bit., AC = 1 since there is a carry from the D3 to the D4 bit., P = 1 since the accumulator has an odd number of 1s (it has five 1s)., Example 3, Show the status of the CY, AC, and P flags after the addition of 9CH and 64H in, the following instructions., MOV A,#9CH, ADD A,#64H, ;after addition A=00 and CY=1, Solution:, , , , , 9C , + 64 , 100 , , 10011100, 01100100, 00000000, , CY = 1 since there is a carry beyond the D7 bit., AC = 1 since there is a carry from the D3 to the D4 bit., P = 0 since the accumulator has an even number of 1s (it has zero 1s)., , Example 4, Show the status of the CY, AC, and P flags after the addition of 88H and 93H in, the following instructions., MOV A,#88H, , ADD A,#93H, ;after the addition A=1BH,CY=1, Solution:, , , , , 88 , + 93 , 11B , , 10001000, 10010011, 00011011, , CY = 1 since there is a carry beyond the D7 bit., AC = 0 since there is no carry from the D3 to the D4 bit., P = 0 since the accumulator has an even number of 1s (it has four 1s)., , 32, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING

Page 38 :

Review Questions, 1. The flag register in the 8051 is called ________., 2. What is the size of the flag register in the 8051?, 3. Which bits of the PSW register are user-definable?, 4. Find the CY and AC flag bits for the following code., MOV A,#0FFH, ADD A,#01, 5. Find the CY and AC flag bits for the following code., MOV A,#0C2H, ADD A,#3DH, , 7: 8051 REGISTER BANKS AND STACK, The 8051 microcontroller has a total of 128 bytes of RAM. In this, section, we discuss the allocation of these 128 bytes of RAM and examine their, usage as registers and stack., , RAM memory space allocation in the 8051, There are 128 bytes of RAM in the 8051 (some members, notably the, 8052, have 256 bytes of RAM). The 128 bytes of RAM inside the 8051 are, assigned addresses 00 to 7FH. They can be accessed directly as memory locations. These 128 bytes are divided into three different groups as follows., 1. A total of 32 bytes from locations 00 to 1F hex are set aside for register, banks and the stack., 2. A total of 16 bytes from locations 20H to 2FH are set aside for bit-addressable read/write memory., 3. A total of 80 bytes from locations 30H to 7FH are used for read and write, storage, or what is normally called a scratch pad. These 80 locations of, RAM are widely used for the purpose of storing data and parameters by, 8051 programmers. See Figure 5., , Register banks in the 8051, As mentioned earlier, a total of 32 bytes of RAM are set aside for, the register banks and stack. These 32 bytes are divided into four banks, of registers in which each bank has eight registers, R0–R7. RAM locations, from 0 to 7 are set aside for bank 0 of R0–R7 where R0 is RAM location 0,, R1 is RAM location 1, R2 is location 2, and so on, until memory location 7,, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING, , 33

Page 39 :

which belongs to R7 of bank 0. The second, bank of registers R0–R7 starts at RAM, location 08 and goes to location 0FH. The, third bank of R0–R7 starts at memory location 10H and goes to location 17H. Finally,, RAM locations 18H to 1FH are set aside, for the fourth bank of R0–R7. Figure 6, shows how the 32 bytes are allocated into, four banks:, As we can see from Figure 6, bank 1, uses the same RAM space as the stack. This, is a major problem in programming the 8051., We must either not use register bank 1 or, allocate another area of RAM for the stack., This will be discussed below., , 7F, , Scratch pad RAM, 30, 2F, Bit-addressable RAM, 20, 1F, , Register bank 3, , 18, 17, , Register bank 2, , 10, 0F, Register bank 1 (Stack), 08, 07, , Default register bank, , Register bank 0, 00, , If RAM locations 00–1F are set aside, for the four register banks, which register Figure 5. RAM Allocation in the 8051, bank of R0–R7 do we have access to when, the 8051 is powered up? The answer is register bank 0; that is, RAM locations, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 are accessed with the names R0, R1, R2, R3, R4, R5,, R6, and R7 when programming the 8051. It is much easier to refer to these, RAM locations with names R0, R1, and so on, than by their memory locations. Examples 5 and 6 clarify this concept., , How to switch register banks, As stated above, register bank 0 is the default when the 8051 is powered up. We can switch to other banks by use of the PSW register. Bits D4, and D3 of the PSW are used to select the desired register bank, as shown in, Table 3., , Bank 0, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0, , R7, R6, R5, R4, R3, R2, R1, R0, , Bank 1, F, E, D, C, B, A, 9, 8, , R7, R6, R5, R4, R3, R2, R1, R0, , Bank 3, , Bank 2, 17, 16, 15, 14, 13, 12, 11, 10, , R7, R6, R5, R4, R3, R2, R1, R0, , 1F, 1E, 1D, 1C, 1B, 1A, 19, 18, , R7, R6, R5, R4, R3, R2, R1, R0, , Figure 6. 8051 Register Banks and their RAM Addresses, , 34, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING

Page 40 :

Example 5, State the contents of the RAM locations after the following program:, , , , , , , MOV, MOV, MOV, MOV, MOV, , R0,#99H, R1,#85H, R2,#3FH, R7,#63H, R5,#12H, , ;load, ;load, ;load, ;load, ;load, , R0, R1, R2, R7, R5, , with, with, with, with, with, , value, value, value, value, value, , 99H, 85H, 3FH, 63H, 12H, , Solution:, After the execution of the above program, we have the following:, RAM location 0 has value 99H, RAM location 1 has value 85H, RAM location 2 has value 3FH RAM location 7 has value 63H, RAM location 5 has value 12H , Example 6, Repeat Example 5 using RAM addresses instead of register names., Solution:, This is called direct addressing mode and uses the RAM address location for the, destination address., , , , , , , MOV, MOV, MOV, MOV, MOV, , 00,#99H, 01,#85H, 02,#3FH, 07,#63H, 05,#12H, , Table 3. PSW Bits Bank Selection, RS1 (PSW.4) RS0 (PSW.3), Bank 0, Bank 1, Bank 2, Bank 3, , 0, 0, 1, 1, , 0, 1, 0, 1, , ;load, ;load, ;load, ;load, ;load, , R0, R1, R2, R7, R5, , with, with, with, with, with, , value, value, value, value, value, , 99H, 85H, 3FH, 63H, 12H, , The D3 and D4 bits of register PSW, are often referred to as PSW.4 and PSW.3 since, they can be accessed by the bit-addressable, instructions SETB and CLR. For example,, “SETB PSW.3” will make PSW.3 = 1 and, select bank register 1. See Example 7., , Stack in the 8051, , The stack is a section of RAM used by the CPU to store information, temporarily. This information could be data or an address. The CPU needs, this storage area since there are only a limited number of registers., , How stacks are accessed in the 8051, If the stack is a section of RAM, there must be registers inside the CPU, to point to it. The register used to access the stack is called the SP (stack pointer), register. The stack pointer in the 8051 is only 8 bits wide, which means that it, 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING, , 35

Page 41 :

Example 7, State the contents of the RAM locations after the following program:, , , , , , , , SETB PSW.4, MOV R0,#99H, MOV R1,#85H, MOV R2,#3FH, MOV R7,#63H, MOV R5,#12H, , ;select bank 2, ;load R0 with value, ;load R1 with value, ;load R2 with value, ;load R7 with value, ;load R5 with value, , 99H, 85H, 3FH, 63H, 12H, , Solution:, By default, PSW.3=0 and PSW.4=0; therefore, the instruction “SETB PSW.4”, sets RS1=1 and RS0=0, thereby selecting register bank 2. Register bank 2 uses, RAM locations 10H–17H. After the execution of the above program, we have the, following:, RAM location 10H has value 99H RAM location 11H has value 85H, RAM location 12H has value 3FH RAM location 17H has value 63H, RAM location 15H has value 12H, can take values of 00 to FFH. When the 8051 is powered up, the SP register, contains value 07. This means that RAM location 08 is the first location used, for the stack by the 8051. The storing of a CPU register in the stack is called a, PUSH, and pulling the contents off the stack back into a CPU register is called, a POP. In other words, a register is pushed onto the stack to save it and popped, off the stack to retrieve it. The job of the SP is very critical when push and pop, actions are performed. To see how the stack works, let’s look at the PUSH and, POP instructions., , Pushing onto the stack, In the 8051, the stack pointer points to the last used location of the, stack. As we push data onto the stack, the stack pointer is incremented by, one. Notice that this is different from many microprocessors, notably x86, processors in which the SP is decremented when data is pushed onto the, stack. Examining Example 8, we see that as each PUSH is executed, the contents of the register are saved on the stack and SP is incremented by 1. Notice, that for every byte of data saved on the stack, SP is incremented only once., Notice also that to push the registers onto the stack we must use their RAM, addresses. For example, the instruction “PUSH 1” pushes register R1 onto, the stack., , Popping from the stack, Popping the contents of the stack back into a given register is the opposite process of pushing. With every pop, the top byte of the stack is copied to, the register specified by the instruction and the stack pointer is decremented, once. Example 9 demonstrates the POP instruction., , 36, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING

Page 43 :

The upper limit of the stack, As mentioned earlier, locations 08 to 1F in the 8051 RAM can be used, for the stack. This is because locations 20–2FH of RAM are reserved for bitaddressable memory and must not be used by the stack. If in a given program, we need more than 24 bytes (08 to 1FH = 24 bytes) of stack, we can change, the SP to point to RAM locations 30–7FH. This is done with the instruction, “MOV SP,#xx”., , CALL instruction and the stack, In addition to using the stack to save registers, the CPU also uses the, stack to save the address of the instruction just below the CALL instruction., This is how the CPU knows where to resume when it returns from the called, subroutine., , Stack and bank 1 conflict, Recall from our earlier discussion that the stack pointer register, points to the current RAM location available for the stack. As data is pushed, onto the stack, SP is incremented. Conversely, it is decremented as data is, popped off the stack into the registers. The reason that the SP is incremented, after the push is to make sure that the stack is growing toward RAM location 7FH, from lower addresses to upper addresses. If the stack pointer were, decremented after push instructions, we would be using RAM locations 7, 6, 5,, and so on, which belong to R7 to R0 of bank 0, the default register bank., This incrementing of the stack pointer for push instructions also ensures that, the stack will not reach location 0 at the bottom of RAM, and consequently, run out of space for the stack. However, there is a problem with the default, setting of the stack. Since SP = 07 when the 8051 is powered up, the first, location of the stack is RAM location 08, which also belongs to register R0, of register bank 1. In other words, register bank 1 and the stack are using the, same memory space. If in a given program we need to use register banks 1, and 2, we can reallocate another section of RAM to the stack. For example,, we can allocate RAM locations 60H and higher to the stack, as shown in, Example 10., , Viewing registers and memory with a simulator, Many assemblers and C compilers come with a simulator. Simulators, allow us to view the contents of registers and memory after executing, each instruction (single-stepping). We strongly recommend that you use, a simulator to single-step some of the programs in this chapter. Singlestepping a program with a simulator gives us a deeper understanding, , 38, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING

Page 44 :

Example 10, Show the stack and stack pointer for the following instructions., , MOV SP,#5FH, ;make RAM location 60H, ;first stack location, MOV R2,#25H, MOV R1,#12H, MOV R4,#0F3H, PUSH 2, PUSH 1, PUSH 4, Solution:, After PUSH 2, , After PUSH 1, , After PUSH 4, , 63, , 63, , 63, , 63, , 62, , 62, , 62, , 62, , F3, , 61, , 61, , 61, , 12, , 61, , 12, , 60, , 60, , 60, , 25, , 60, , 25, , Start SP = 5F, , 25, , SP = 60, , SP = 61, , SP = 62, , of microcontroller architecture, in addition to the fact that we can use it to find, errors in our programs. Figures 7 through 10 show screenshots for 8051 simulators from ProView 32 and Keil. See www.MicroDigitalEd.com for tutorials, on how to use the simulators., , Figure 7. Register’s Screen from ProView 32 Simulator, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING, , 39

Page 45 :

Figure 8. 128-Byte Memory Space from ProView 32 Simulator, , Figure 9. Register’s Screen from Keil Simulator, , 40, , 8051 ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING

Page 46 :