Page 2 :

Artificial Intelligence, A Modern Approach, Third Edition

Page 3 :

PRENTICE HALL SERIES, IN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig, Editors, , F ORSYTH & P ONCE, G RAHAM, J URAFSKY & M ARTIN, N EAPOLITAN, RUSSELL & N ORVIG, , Computer Vision: A Modern Approach, ANSI Common Lisp, Speech and Language Processing, 2nd ed., Learning Bayesian Networks, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 3rd ed.

Page 4 :

Artificial Intelligence, A Modern Approach, Third Edition, Stuart J. Russell and Peter Norvig, , Contributing writers:, Ernest Davis, Douglas D. Edwards, David Forsyth, Nicholas J. Hay, Jitendra M. Malik, Vibhu Mittal, Mehran Sahami, Sebastian Thrun, , Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River, Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montreal Toronto, Delhi Mexico City Sao Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo

Page 5 :

Pearson Education Limited, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England, and Associated Companies throughout the world, Visit us on the World Wide Web at:, www.pearsonglobaleditions.com, © Pearson Education Limited 2016, The rights of Stuart J. Russell and Peter Norvig to be identified as the authors of this work have, been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988., Authorized adaptation from the United States edition, entitled Artificial Intelligence: A Modern, Approach, Third Edition, ISBN 9780136042594, by Stuart J. Russell and Peter Norvig published, by Pearson Education © 2010., All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or, otherwise, without either the prior written permission of the publisher or a license permitting, restricted copying in the United Kingdom issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron, House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS., All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. The use of any trademark, in this text does not vest in the author or publisher any trademark ownership rights in such, trademarks, nor does the use of such trademarks imply any affiliation with or endorsement of this, book by such owners., British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data, A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library, 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1, ISBN 10: 1292153962, ISBN 13: 9781292153964, , Printed and bound in Malaysia

Page 6 :

For Loy, Gordon, Lucy, George, and Isaac — S.J.R., For Kris, Isabella, and Juliet — P.N.

Page 7 :

This page intentionally left blank

Page 8 :

Preface, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a big field, and this is a big book. We have tried to explore the, full breadth of the field, which encompasses logic, probability, and continuous mathematics;, perception, reasoning, learning, and action; and everything from microelectronic devices to, robotic planetary explorers. The book is also big because we go into some depth., The subtitle of this book is “A Modern Approach.” The intended meaning of this rather, empty phrase is that we have tried to synthesize what is now known into a common framework, rather than trying to explain each subfield of AI in its own historical context. We, apologize to those whose subfields are, as a result, less recognizable., , New to this edition, This edition captures the changes in AI that have taken place since the last edition in 2003., There have been important applications of AI technology, such as the widespread deployment of practical speech recognition, machine translation, autonomous vehicles, and household robotics. There have been algorithmic landmarks, such as the solution of the game of, checkers. And there has been a great deal of theoretical progress, particularly in areas such, as probabilistic reasoning, machine learning, and computer vision. Most important from our, point of view is the continued evolution in how we think about the field, and thus how we, organize the book. The major changes are as follows:, • We place more emphasis on partially observable and nondeterministic environments,, especially in the nonprobabilistic settings of search and planning. The concepts of, belief state (a set of possible worlds) and state estimation (maintaining the belief state), are introduced in these settings; later in the book, we add probabilities., • In addition to discussing the types of environments and types of agents, we now cover, in more depth the types of representations that an agent can use. We distinguish among, atomic representations (in which each state of the world is treated as a black box),, factored representations (in which a state is a set of attribute/value pairs), and structured, representations (in which the world consists of objects and relations between them)., • Our coverage of planning goes into more depth on contingent planning in partially, observable environments and includes a new approach to hierarchical planning., • We have added new material on first-order probabilistic models, including open-universe, models for cases where there is uncertainty as to what objects exist., • We have completely rewritten the introductory machine-learning chapter, stressing a, wider variety of more modern learning algorithms and placing them on a firmer theoretical footing., • We have expanded coverage of Web search and information extraction, and of techniques for learning from very large data sets., • 20% of the citations in this edition are to works published after 2003., • We estimate that about 20% of the material is brand new. The remaining 80% reflects, older work but has been largely rewritten to present a more unified picture of the field., vii

Page 9 :

viii, , Preface, , Overview of the book, , NEW TERM, , The main unifying theme is the idea of an intelligent agent. We define AI as the study of, agents that receive percepts from the environment and perform actions. Each such agent implements a function that maps percept sequences to actions, and we cover different ways to, represent these functions, such as reactive agents, real-time planners, and decision-theoretic, systems. We explain the role of learning as extending the reach of the designer into unknown, environments, and we show how that role constrains agent design, favoring explicit knowledge representation and reasoning. We treat robotics and vision not as independently defined, problems, but as occurring in the service of achieving goals. We stress the importance of the, task environment in determining the appropriate agent design., Our primary aim is to convey the ideas that have emerged over the past fifty years of AI, research and the past two millennia of related work. We have tried to avoid excessive formality in the presentation of these ideas while retaining precision. We have included pseudocode, algorithms to make the key ideas concrete; our pseudocode is described in Appendix B., This book is primarily intended for use in an undergraduate course or course sequence., The book has 27 chapters, each requiring about a week’s worth of lectures, so working, through the whole book requires a two-semester sequence. A one-semester course can use, selected chapters to suit the interests of the instructor and students. The book can also be, used in a graduate-level course (perhaps with the addition of some of the primary sources, suggested in the bibliographical notes). Sample syllabi are available at the book’s Web site,, aima.cs.berkeley.edu. The only prerequisite is familiarity with basic concepts of, computer science (algorithms, data structures, complexity) at a sophomore level. Freshman, calculus and linear algebra are useful for some of the topics; the required mathematical background is supplied in Appendix A., Exercises are given at the end of each chapter. Exercises requiring significant programming are marked with a keyboard icon. These exercises can best be solved by taking, advantage of the code repository at aima.cs.berkeley.edu. Some of them are large, enough to be considered term projects. A number of exercises require some investigation of, the literature; these are marked with a book icon., Throughout the book, important points are marked with a pointing icon. We have included an extensive index of around 6,000 items to make it easy to find things in the book., Wherever a new term is first defined, it is also marked in the margin., , About the Web site, aima.cs.berkeley.edu, the Web site for the book, contains, • implementations of the algorithms in the book in several programming languages,, • a list of over 1000 schools that have used the book, many with links to online course, materials and syllabi,, • an annotated list of over 800 links to sites around the Web with useful AI content,, • a chapter-by-chapter list of supplementary material and links,, • instructions on how to join a discussion group for the book,

Page 10 :

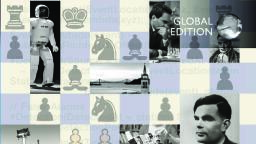

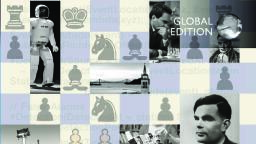

Preface, , ix, • instructions on how to contact the authors with questions or comments,, • instructions on how to report errors in the book, in the likely event that some exist, and, • slides and other materials for instructors., Pearson offers many different products around the world to facilitate learning. In countries, outside the United States, some products and services related to this textbook may not be, available due to copyright and/or permissions restrictions. If you have questions, you can, contact your local office by visiting www.pearsonhighered.com/international or you can contact your local Pearson representative., , About the cover, The cover depicts the final position from the decisive game 6 of the 1997 match between, chess champion Garry Kasparov and program D EEP B LUE . Kasparov, playing Black, was, forced to resign, making this the first time a computer had beaten a world champion in a, chess match. Kasparov is shown at the top. To his left is the Asimo humanoid robot and, to his right is Thomas Bayes (1702–1761), whose ideas about probability as a measure of, belief underlie much of modern AI technology. Below that we see a Mars Exploration Rover,, a robot that landed on Mars in 2004 and has been exploring the planet ever since. To the, right is Alan Turing (1912–1954), whose fundamental work defined the fields of computer, science in general and artificial intelligence in particular. At the bottom is Shakey (1966–, 1972), the first robot to combine perception, world-modeling, planning, and learning. With, Shakey is project leader Charles Rosen (1917–2002). At the bottom right is Aristotle (384, B . C .–322 B . C .), who pioneered the study of logic; his work was state of the art until the 19th, century (copy of a bust by Lysippos). At the bottom left, lightly screened behind the authors’, names, is a planning algorithm by Aristotle from De Motu Animalium in the original Greek., Behind the title is a portion of the CPSC Bayesian network for medical diagnosis (Pradhan, et al., 1994). Behind the chess board is part of a Bayesian logic model for detecting nuclear, explosions from seismic signals., Credits: Stan Honda/Getty (Kasparaov), Library of Congress (Bayes), NASA (Mars, rover), National Museum of Rome (Aristotle), Peter Norvig (book), Ian Parker (Berkeley, skyline), Shutterstock (Asimo, Chess pieces), Time Life/Getty (Shakey, Turing)., , Acknowledgments, This book would not have been possible without the many contributors whose names did not, make it to the cover. Jitendra Malik and David Forsyth wrote Chapter 24 (computer vision), and Sebastian Thrun wrote Chapter 25 (robotics). Vibhu Mittal wrote part of Chapter 22, (natural language). Nick Hay, Mehran Sahami, and Ernest Davis wrote some of the exercises., Zoran Duric (George Mason), Thomas C. Henderson (Utah), Leon Reznik (RIT), Michael, Gourley (Central Oklahoma) and Ernest Davis (NYU) reviewed the manuscript and made, helpful suggestions. We thank Ernie Davis in particular for his tireless ability to read multiple, drafts and help improve the book. Nick Hay whipped the bibliography into shape and on, deadline stayed up to 5:30 AM writing code to make the book better. Jon Barron formatted, and improved the diagrams in this edition, while Tim Huang, Mark Paskin, and Cynthia

Page 13 :

About the Authors, Stuart Russell was born in 1962 in Portsmouth, England. He received his B.A. with firstclass honours in physics from Oxford University in 1982, and his Ph.D. in computer science, from Stanford in 1986. He then joined the faculty of the University of California at Berkeley,, where he is a professor of computer science, director of the Center for Intelligent Systems,, and holder of the Smith–Zadeh Chair in Engineering. In 1990, he received the Presidential, Young Investigator Award of the National Science Foundation, and in 1995 he was cowinner, of the Computers and Thought Award. He was a 1996 Miller Professor of the University of, California and was appointed to a Chancellor’s Professorship in 2000. In 1998, he gave the, Forsythe Memorial Lectures at Stanford University. He is a Fellow and former Executive, Council member of the American Association for Artificial Intelligence. He has published, over 100 papers on a wide range of topics in artificial intelligence. His other books include, The Use of Knowledge in Analogy and Induction and (with Eric Wefald) Do the Right Thing:, Studies in Limited Rationality., Peter Norvig is currently Director of Research at Google, Inc., and was the director responsible for the core Web search algorithms from 2002 to 2005. He is a Fellow of the American, Association for Artificial Intelligence and the Association for Computing Machinery. Previously, he was head of the Computational Sciences Division at NASA Ames Research Center,, where he oversaw NASA’s research and development in artificial intelligence and robotics,, and chief scientist at Junglee, where he helped develop one of the first Internet information, extraction services. He received a B.S. in applied mathematics from Brown University and, a Ph.D. in computer science from the University of California at Berkeley. He received the, Distinguished Alumni and Engineering Innovation awards from Berkeley and the Exceptional, Achievement Medal from NASA. He has been a professor at the University of Southern California and a research faculty member at Berkeley. His other books are Paradigms of AI, Programming: Case Studies in Common Lisp and Verbmobil: A Translation System for Faceto-Face Dialog and Intelligent Help Systems for UNIX., , xii

Page 14 :

Contents, I Artificial Intelligence, 1 Introduction, 1.1, What Is AI? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 1.2, The Foundations of Artificial Intelligence . . . . . . . . ., 1.3, The History of Artificial Intelligence . . . . . . . . . . ., 1.4, The State of the Art . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 1.5, Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, 2 Intelligent Agents, 2.1, Agents and Environments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 2.2, Good Behavior: The Concept of Rationality . . . . . . ., 2.3, The Nature of Environments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 2.4, The Structure of Agents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 2.5, Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , 1, 1, 5, 16, 28, 29, , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , 34, 34, 36, 40, 46, 59, , 3 Solving Problems by Searching, 3.1, Problem-Solving Agents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 3.2, Example Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 3.3, Searching for Solutions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 3.4, Uninformed Search Strategies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 3.5, Informed (Heuristic) Search Strategies . . . . . . . . . ., 3.6, Heuristic Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 3.7, Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , 64, 64, 69, 75, 81, 92, 102, 108, , 4 Beyond Classical Search, 4.1, Local Search Algorithms and Optimization Problems . ., 4.2, Local Search in Continuous Spaces . . . . . . . . . . . ., 4.3, Searching with Nondeterministic Actions . . . . . . . . ., 4.4, Searching with Partial Observations . . . . . . . . . . . ., 4.5, Online Search Agents and Unknown Environments . . ., 4.6, Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , 120, 120, 129, 133, 138, 147, 153, , 5 Adversarial Search, 5.1, Games . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 5.2, Optimal Decisions in Games ., 5.3, Alpha–Beta Pruning . . . . . ., 5.4, Imperfect Real-Time Decisions, 5.5, Stochastic Games . . . . . . ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , 161, 161, 163, 167, 171, 177, , II Problem-solving, , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , xiii, , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., .

Page 15 :

xiv, , Contents, 5.6, 5.7, 5.8, 5.9, , Partially Observable Games . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., State-of-the-Art Game Programs . . . . . . . . . . . . ., Alternative Approaches . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , 180, 185, 187, 189, , 6 Constraint Satisfaction Problems, 6.1, Defining Constraint Satisfaction Problems . . . . . . . ., 6.2, Constraint Propagation: Inference in CSPs . . . . . . . ., 6.3, Backtracking Search for CSPs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 6.4, Local Search for CSPs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 6.5, The Structure of Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 6.6, Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , 202, 202, 208, 214, 220, 222, 227, , 7 Logical Agents, 7.1, Knowledge-Based Agents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 7.2, The Wumpus World . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 7.3, Logic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 7.4, Propositional Logic: A Very Simple Logic . . . . . . . ., 7.5, Propositional Theorem Proving . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 7.6, Effective Propositional Model Checking . . . . . . . . ., 7.7, Agents Based on Propositional Logic . . . . . . . . . . ., 7.8, Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , 234, 235, 236, 240, 243, 249, 259, 265, 274, , 8 First-Order Logic, 8.1, Representation Revisited . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 8.2, Syntax and Semantics of First-Order Logic . . . . . . . ., 8.3, Using First-Order Logic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 8.4, Knowledge Engineering in First-Order Logic . . . . . . ., 8.5, Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , 285, 285, 290, 300, 307, 313, , ., ., ., ., ., ., , 322, 322, 325, 330, 337, 345, 357, , 10 Classical Planning, 10.1 Definition of Classical Planning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 10.2 Algorithms for Planning as State-Space Search . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 10.3 Planning Graphs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., , 366, 366, 373, 379, , III Knowledge, reasoning, and planning, , 9 Inference in First-Order Logic, 9.1, Propositional vs. First-Order Inference . . . . . . . . . ., 9.2, Unification and Lifting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 9.3, Forward Chaining . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 9.4, Backward Chaining . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 9.5, Resolution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 9.6, Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., .

Page 16 :

Contents, , xv, 10.4, 10.5, 10.6, , Other Classical Planning Approaches . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., Analysis of Planning Approaches . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises . . . . . . . . ., , 387, 392, 393, , 11 Planning and Acting in the Real World, 11.1 Time, Schedules, and Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 11.2 Hierarchical Planning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 11.3 Planning and Acting in Nondeterministic Domains . . . ., 11.4 Multiagent Planning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 11.5 Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , 401, 401, 406, 415, 425, 430, , 12 Knowledge Representation, 12.1 Ontological Engineering . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 12.2 Categories and Objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 12.3 Events . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 12.4 Mental Events and Mental Objects . . . . . . . . . . . ., 12.5 Reasoning Systems for Categories . . . . . . . . . . . ., 12.6 Reasoning with Default Information . . . . . . . . . . ., 12.7 The Internet Shopping World . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 12.8 Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , 437, 437, 440, 446, 450, 453, 458, 462, 467, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , 480, 480, 483, 490, 494, 495, 499, 503, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , 510, 510, 513, 518, 522, 530, 539, 546, 551, , 15 Probabilistic Reasoning over Time, 15.1 Time and Uncertainty . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., , 566, 566, , IV Uncertain knowledge and reasoning, 13 Quantifying Uncertainty, 13.1 Acting under Uncertainty . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 13.2 Basic Probability Notation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 13.3 Inference Using Full Joint Distributions . . . . . . . . . ., 13.4 Independence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 13.5 Bayes’ Rule and Its Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 13.6 The Wumpus World Revisited . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 13.7 Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, 14 Probabilistic Reasoning, 14.1 Representing Knowledge in an Uncertain Domain . . . ., 14.2 The Semantics of Bayesian Networks . . . . . . . . . . ., 14.3 Efficient Representation of Conditional Distributions . . ., 14.4 Exact Inference in Bayesian Networks . . . . . . . . . ., 14.5 Approximate Inference in Bayesian Networks . . . . . ., 14.6 Relational and First-Order Probability Models . . . . . ., 14.7 Other Approaches to Uncertain Reasoning . . . . . . . ., 14.8 Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., .

Page 17 :

xvi, , Contents, 15.2, 15.3, 15.4, 15.5, 15.6, 15.7, , Inference in Temporal Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., Hidden Markov Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., Kalman Filters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., Dynamic Bayesian Networks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., Keeping Track of Many Objects . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , 16 Making Simple Decisions, 16.1 Combining Beliefs and Desires under Uncertainty . . . ., 16.2 The Basis of Utility Theory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 16.3 Utility Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 16.4 Multiattribute Utility Functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 16.5 Decision Networks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 16.6 The Value of Information . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 16.7 Decision-Theoretic Expert Systems . . . . . . . . . . . ., 16.8 Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, 17 Making Complex Decisions, 17.1 Sequential Decision Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 17.2 Value Iteration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 17.3 Policy Iteration . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 17.4 Partially Observable MDPs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 17.5 Decisions with Multiple Agents: Game Theory . . . . . ., 17.6 Mechanism Design . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 17.7 Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , 570, 578, 584, 590, 599, 603, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , 610, 610, 611, 615, 622, 626, 628, 633, 636, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , 645, 645, 652, 656, 658, 666, 679, 684, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , 693, 693, 695, 697, 708, 713, 717, 727, 737, 744, 748, 753, 757, , 19 Knowledge in Learning, 19.1 A Logical Formulation of Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., , 768, 768, , V, , Learning, , 18 Learning from Examples, 18.1 Forms of Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 18.2 Supervised Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 18.3 Learning Decision Trees . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 18.4 Evaluating and Choosing the Best Hypothesis . . . . . ., 18.5 The Theory of Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 18.6 Regression and Classification with Linear Models . . . ., 18.7 Artificial Neural Networks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 18.8 Nonparametric Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 18.9 Support Vector Machines . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 18.10 Ensemble Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 18.11 Practical Machine Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 18.12 Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises

Page 18 :

Contents, , xvii, 19.2, 19.3, 19.4, 19.5, 19.6, , Knowledge in Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., Explanation-Based Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., Learning Using Relevance Information . . . . . . . . . ., Inductive Logic Programming . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , 20 Learning Probabilistic Models, 20.1 Statistical Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 20.2 Learning with Complete Data . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 20.3 Learning with Hidden Variables: The EM Algorithm . . ., 20.4 Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, 21 Reinforcement Learning, 21.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 21.2 Passive Reinforcement Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 21.3 Active Reinforcement Learning . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 21.4 Generalization in Reinforcement Learning . . . . . . . ., 21.5 Policy Search . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 21.6 Applications of Reinforcement Learning . . . . . . . . ., 21.7 Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , 777, 780, 784, 788, 797, , ., ., ., ., , 802, 802, 806, 816, 825, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , 830, 830, 832, 839, 845, 848, 850, 853, , 22 Natural Language Processing, 22.1 Language Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 22.2 Text Classification . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 22.3 Information Retrieval . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 22.4 Information Extraction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 22.5 Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , 860, 860, 865, 867, 873, 882, , 23 Natural Language for Communication, 23.1 Phrase Structure Grammars . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 23.2 Syntactic Analysis (Parsing) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 23.3 Augmented Grammars and Semantic Interpretation . . ., 23.4 Machine Translation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 23.5 Speech Recognition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 23.6 Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., , 888, 888, 892, 897, 907, 912, 918, , 24 Perception, 24.1 Image Formation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 24.2 Early Image-Processing Operations . . . . . . ., 24.3 Object Recognition by Appearance . . . . . . ., 24.4 Reconstructing the 3D World . . . . . . . . . ., 24.5 Object Recognition from Structural Information, , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , 928, 929, 935, 942, 947, 957, , VI Communicating, perceiving, and acting, , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., .

Page 19 :

xviii, , Contents, 24.6, 24.7, , Using Vision . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises . . . . . . . . ., , 25 Robotics, 25.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 25.2 Robot Hardware . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 25.3 Robotic Perception . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 25.4 Planning to Move . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 25.5 Planning Uncertain Movements . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 25.6 Moving . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 25.7 Robotic Software Architectures . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 25.8 Application Domains . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., 25.9 Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , 961, 965, , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , 971, . 971, . 973, . 978, . 986, . 993, . 997, . 1003, . 1006, . 1010, , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , 1020, 1020, 1026, 1034, 1040, , ., ., ., ., , 1044, 1044, 1047, 1049, 1051, , VII Conclusions, 26 Philosophical Foundations, 26.1 Weak AI: Can Machines Act Intelligently? . . . . . . . ., 26.2 Strong AI: Can Machines Really Think? . . . . . . . . ., 26.3 The Ethics and Risks of Developing Artificial Intelligence, 26.4 Summary, Bibliographical and Historical Notes, Exercises, 27 AI: The Present and Future, 27.1 Agent Components . . . . . . . . . ., 27.2 Agent Architectures . . . . . . . . . ., 27.3 Are We Going in the Right Direction?, 27.4 What If AI Does Succeed? . . . . . ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., ., ., ., ., , ., ., ., ., , A Mathematical background, 1053, A.1 Complexity Analysis and O() Notation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1053, A.2 Vectors, Matrices, and Linear Algebra . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1055, A.3 Probability Distributions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1057, B Notes on Languages and Algorithms, B.1 Defining Languages with Backus–Naur Form (BNF) . . . . . . . . . . . ., B.2 Describing Algorithms with Pseudocode . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., B.3 Online Help . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ., , 1060, 1060, 1061, 1062, , Bibliography, , 1063, , Index, , 1095

Page 20 :

1, , INTRODUCTION, , In which we try to explain why we consider artificial intelligence to be a subject, most worthy of study, and in which we try to decide what exactly it is, this being a, good thing to decide before embarking., , INTELLIGENCE, , ARTIFICIAL, INTELLIGENCE, , 1.1, , RATIONALITY, , We call ourselves Homo sapiens—man the wise—because our intelligence is so important, to us. For thousands of years, we have tried to understand how we think; that is, how a mere, handful of matter can perceive, understand, predict, and manipulate a world far larger and, more complicated than itself. The field of artificial intelligence, or AI, goes further still: it, attempts not just to understand but also to build intelligent entities., AI is one of the newest fields in science and engineering. Work started in earnest soon, after World War II, and the name itself was coined in 1956. Along with molecular biology,, AI is regularly cited as the “field I would most like to be in” by scientists in other disciplines., A student in physics might reasonably feel that all the good ideas have already been taken by, Galileo, Newton, Einstein, and the rest. AI, on the other hand, still has openings for several, full-time Einsteins and Edisons., AI currently encompasses a huge variety of subfields, ranging from the general (learning, and perception) to the specific, such as playing chess, proving mathematical theorems, writing, poetry, driving a car on a crowded street, and diagnosing diseases. AI is relevant to any, intellectual task; it is truly a universal field., , W HAT I S AI?, We have claimed that AI is exciting, but we have not said what it is. In Figure 1.1 we see, eight definitions of AI, laid out along two dimensions. The definitions on top are concerned, with thought processes and reasoning, whereas the ones on the bottom address behavior. The, definitions on the left measure success in terms of fidelity to human performance, whereas, the ones on the right measure against an ideal performance measure, called rationality. A, system is rational if it does the “right thing,” given what it knows., Historically, all four approaches to AI have been followed, each by different people, with different methods. A human-centered approach must be in part an empirical science, in1

Page 21 :

2, , Chapter 1., , Introduction, , Thinking Humanly, , Thinking Rationally, , “The exciting new effort to make computers think . . . machines with minds, in the, full and literal sense.” (Haugeland, 1985), , “The study of mental faculties through the, use of computational models.”, (Charniak and McDermott, 1985), , “[The automation of] activities that we, associate with human thinking, activities, such as decision-making, problem solving, learning . . .” (Bellman, 1978), , “The study of the computations that make, it possible to perceive, reason, and act.”, (Winston, 1992), , Acting Humanly, , Acting Rationally, , “The art of creating machines that perform functions that require intelligence, when performed by people.” (Kurzweil,, 1990), , “Computational Intelligence is the study, of the design of intelligent agents.” (Poole, et al., 1998), , “The study of how to make computers do, things at which, at the moment, people are, better.” (Rich and Knight, 1991), , “AI . . . is concerned with intelligent behavior in artifacts.” (Nilsson, 1998), , Figure 1.1, , Some definitions of artificial intelligence, organized into four categories., , volving observations and hypotheses about human behavior. A rationalist1 approach involves, a combination of mathematics and engineering. The various group have both disparaged and, helped each other. Let us look at the four approaches in more detail., , 1.1.1 Acting humanly: The Turing Test approach, TURING TEST, , NATURAL LANGUAGE, PROCESSING, KNOWLEDGE, REPRESENTATION, AUTOMATED, REASONING, , MACHINE LEARNING, , The Turing Test, proposed by Alan Turing (1950), was designed to provide a satisfactory, operational definition of intelligence. A computer passes the test if a human interrogator, after, posing some written questions, cannot tell whether the written responses come from a person, or from a computer. Chapter 26 discusses the details of the test and whether a computer would, really be intelligent if it passed. For now, we note that programming a computer to pass a, rigorously applied test provides plenty to work on. The computer would need to possess the, following capabilities:, • natural language processing to enable it to communicate successfully in English;, • knowledge representation to store what it knows or hears;, • automated reasoning to use the stored information to answer questions and to draw, new conclusions;, • machine learning to adapt to new circumstances and to detect and extrapolate patterns., 1 By distinguishing between human and rational behavior, we are not suggesting that humans are necessarily, “irrational” in the sense of “emotionally unstable” or “insane.” One merely need note that we are not perfect:, not all chess players are grandmasters; and, unfortunately, not everyone gets an A on the exam. Some systematic, errors in human reasoning are cataloged by Kahneman et al. (1982).

Page 22 :

Section 1.1., , TOTAL TURING TEST, , What Is AI?, , 3, , Turing’s test deliberately avoided direct physical interaction between the interrogator and the, computer, because physical simulation of a person is unnecessary for intelligence. However,, the so-called total Turing Test includes a video signal so that the interrogator can test the, subject’s perceptual abilities, as well as the opportunity for the interrogator to pass physical, objects “through the hatch.” To pass the total Turing Test, the computer will need, , COMPUTER VISION, , • computer vision to perceive objects, and, , ROBOTICS, , • robotics to manipulate objects and move about., These six disciplines compose most of AI, and Turing deserves credit for designing a test, that remains relevant 60 years later. Yet AI researchers have devoted little effort to passing, the Turing Test, believing that it is more important to study the underlying principles of intelligence than to duplicate an exemplar. The quest for “artificial flight” succeeded when the, Wright brothers and others stopped imitating birds and started using wind tunnels and learning about aerodynamics. Aeronautical engineering texts do not define the goal of their field, as making “machines that fly so exactly like pigeons that they can fool even other pigeons.”, , 1.1.2 Thinking humanly: The cognitive modeling approach, , COGNITIVE SCIENCE, , If we are going to say that a given program thinks like a human, we must have some way of, determining how humans think. We need to get inside the actual workings of human minds., There are three ways to do this: through introspection—trying to catch our own thoughts as, they go by; through psychological experiments—observing a person in action; and through, brain imaging—observing the brain in action. Once we have a sufficiently precise theory of, the mind, it becomes possible to express the theory as a computer program. If the program’s, input–output behavior matches corresponding human behavior, that is evidence that some of, the program’s mechanisms could also be operating in humans. For example, Allen Newell, and Herbert Simon, who developed GPS, the “General Problem Solver” (Newell and Simon,, 1961), were not content merely to have their program solve problems correctly. They were, more concerned with comparing the trace of its reasoning steps to traces of human subjects, solving the same problems. The interdisciplinary field of cognitive science brings together, computer models from AI and experimental techniques from psychology to construct precise, and testable theories of the human mind., Cognitive science is a fascinating field in itself, worthy of several textbooks and at least, one encyclopedia (Wilson and Keil, 1999). We will occasionally comment on similarities or, differences between AI techniques and human cognition. Real cognitive science, however, is, necessarily based on experimental investigation of actual humans or animals. We will leave, that for other books, as we assume the reader has only a computer for experimentation., In the early days of AI there was often confusion between the approaches: an author, would argue that an algorithm performs well on a task and that it is therefore a good model, of human performance, or vice versa. Modern authors separate the two kinds of claims;, this distinction has allowed both AI and cognitive science to develop more rapidly. The two, fields continue to fertilize each other, most notably in computer vision, which incorporates, neurophysiological evidence into computational models.

Page 23 :

4, , Chapter 1., , Introduction, , 1.1.3 Thinking rationally: The “laws of thought” approach, SYLLOGISM, , LOGIC, , LOGICIST, , The Greek philosopher Aristotle was one of the first to attempt to codify “right thinking,” that, is, irrefutable reasoning processes. His syllogisms provided patterns for argument structures, that always yielded correct conclusions when given correct premises—for example, “Socrates, is a man; all men are mortal; therefore, Socrates is mortal.” These laws of thought were, supposed to govern the operation of the mind; their study initiated the field called logic., Logicians in the 19th century developed a precise notation for statements about all kinds, of objects in the world and the relations among them. (Contrast this with ordinary arithmetic, notation, which provides only for statements about numbers.) By 1965, programs existed, that could, in principle, solve any solvable problem described in logical notation. (Although, if no solution exists, the program might loop forever.) The so-called logicist tradition within, artificial intelligence hopes to build on such programs to create intelligent systems., There are two main obstacles to this approach. First, it is not easy to take informal, knowledge and state it in the formal terms required by logical notation, particularly when, the knowledge is less than 100% certain. Second, there is a big difference between solving, a problem “in principle” and solving it in practice. Even problems with just a few hundred, facts can exhaust the computational resources of any computer unless it has some guidance, as to which reasoning steps to try first. Although both of these obstacles apply to any attempt, to build computational reasoning systems, they appeared first in the logicist tradition., , 1.1.4 Acting rationally: The rational agent approach, AGENT, , RATIONAL AGENT, , An agent is just something that acts (agent comes from the Latin agere, to do). Of course,, all computer programs do something, but computer agents are expected to do more: operate, autonomously, perceive their environment, persist over a prolonged time period, adapt to, change, and create and pursue goals. A rational agent is one that acts so as to achieve the, best outcome or, when there is uncertainty, the best expected outcome., In the “laws of thought” approach to AI, the emphasis was on correct inferences. Making correct inferences is sometimes part of being a rational agent, because one way to act, rationally is to reason logically to the conclusion that a given action will achieve one’s goals, and then to act on that conclusion. On the other hand, correct inference is not all of rationality; in some situations, there is no provably correct thing to do, but something must still be, done. There are also ways of acting rationally that cannot be said to involve inference. For, example, recoiling from a hot stove is a reflex action that is usually more successful than a, slower action taken after careful deliberation., All the skills needed for the Turing Test also allow an agent to act rationally. Knowledge, representation and reasoning enable agents to reach good decisions. We need to be able to, generate comprehensible sentences in natural language to get by in a complex society. We, need learning not only for erudition, but also because it improves our ability to generate, effective behavior., The rational-agent approach has two advantages over the other approaches. First, it, is more general than the “laws of thought” approach because correct inference is just one, of several possible mechanisms for achieving rationality. Second, it is more amenable to

Page 24 :

Section 1.2., , LIMITED, RATIONALITY, , 1.2, , The Foundations of Artificial Intelligence, , 5, , scientific development than are approaches based on human behavior or human thought. The, standard of rationality is mathematically well defined and completely general, and can be, “unpacked” to generate agent designs that provably achieve it. Human behavior, on the other, hand, is well adapted for one specific environment and is defined by, well, the sum total, of all the things that humans do. This book therefore concentrates on general principles, of rational agents and on components for constructing them. We will see that despite the, apparent simplicity with which the problem can be stated, an enormous variety of issues, come up when we try to solve it. Chapter 2 outlines some of these issues in more detail., One important point to keep in mind: We will see before too long that achieving perfect, rationality—always doing the right thing—is not feasible in complicated environments. The, computational demands are just too high. For most of the book, however, we will adopt the, working hypothesis that perfect rationality is a good starting point for analysis. It simplifies, the problem and provides the appropriate setting for most of the foundational material in, the field. Chapters 5 and 17 deal explicitly with the issue of limited rationality—acting, appropriately when there is not enough time to do all the computations one might like., , T HE F OUNDATIONS OF A RTIFICIAL I NTELLIGENCE, In this section, we provide a brief history of the disciplines that contributed ideas, viewpoints,, and techniques to AI. Like any history, this one is forced to concentrate on a small number, of people, events, and ideas and to ignore others that also were important. We organize the, history around a series of questions. We certainly would not wish to give the impression that, these questions are the only ones the disciplines address or that the disciplines have all been, working toward AI as their ultimate fruition., , 1.2.1 Philosophy, •, •, •, •, , Can formal rules be used to draw valid conclusions?, How does the mind arise from a physical brain?, Where does knowledge come from?, How does knowledge lead to action?, , Aristotle (384–322 B . C .), whose bust appears on the front cover of this book, was the first, to formulate a precise set of laws governing the rational part of the mind. He developed an, informal system of syllogisms for proper reasoning, which in principle allowed one to generate conclusions mechanically, given initial premises. Much later, Ramon Lull (d. 1315) had, the idea that useful reasoning could actually be carried out by a mechanical artifact. Thomas, Hobbes (1588–1679) proposed that reasoning was like numerical computation, that “we add, and subtract in our silent thoughts.” The automation of computation itself was already well, under way. Around 1500, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) designed but did not build a mechanical calculator; recent reconstructions have shown the design to be functional. The first, known calculating machine was constructed around 1623 by the German scientist Wilhelm, Schickard (1592–1635), although the Pascaline, built in 1642 by Blaise Pascal (1623–1662),

Page 25 :

6, , RATIONALISM, DUALISM, , MATERIALISM, , EMPIRICISM, , INDUCTION, , LOGICAL POSITIVISM, OBSERVATION, SENTENCES, CONFIRMATION, THEORY, , Chapter 1., , Introduction, , is more famous. Pascal wrote that “the arithmetical machine produces effects which appear, nearer to thought than all the actions of animals.” Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), built a mechanical device intended to carry out operations on concepts rather than numbers,, but its scope was rather limited. Leibniz did surpass Pascal by building a calculator that, could add, subtract, multiply, and take roots, whereas the Pascaline could only add and subtract. Some speculated that machines might not just do calculations but actually be able to, think and act on their own. In his 1651 book Leviathan, Thomas Hobbes suggested the idea, of an “artificial animal,” arguing “For what is the heart but a spring; and the nerves, but so, many strings; and the joints, but so many wheels.”, It’s one thing to say that the mind operates, at least in part, according to logical rules, and, to build physical systems that emulate some of those rules; it’s another to say that the mind, itself is such a physical system. René Descartes (1596–1650) gave the first clear discussion, of the distinction between mind and matter and of the problems that arise. One problem with, a purely physical conception of the mind is that it seems to leave little room for free will:, if the mind is governed entirely by physical laws, then it has no more free will than a rock, “deciding” to fall toward the center of the earth. Descartes was a strong advocate of the power, of reasoning in understanding the world, a philosophy now called rationalism, and one that, counts Aristotle and Leibnitz as members. But Descartes was also a proponent of dualism., He held that there is a part of the human mind (or soul or spirit) that is outside of nature,, exempt from physical laws. Animals, on the other hand, did not possess this dual quality;, they could be treated as machines. An alternative to dualism is materialism, which holds, that the brain’s operation according to the laws of physics constitutes the mind. Free will is, simply the way that the perception of available choices appears to the choosing entity., Given a physical mind that manipulates knowledge, the next problem is to establish, the source of knowledge. The empiricism movement, starting with Francis Bacon’s (1561–, 1626) Novum Organum,2 is characterized by a dictum of John Locke (1632–1704): “Nothing, is in the understanding, which was not first in the senses.” David Hume’s (1711–1776) A, Treatise of Human Nature (Hume, 1739) proposed what is now known as the principle of, induction: that general rules are acquired by exposure to repeated associations between their, elements. Building on the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) and Bertrand Russell, (1872–1970), the famous Vienna Circle, led by Rudolf Carnap (1891–1970), developed the, doctrine of logical positivism. This doctrine holds that all knowledge can be characterized by, logical theories connected, ultimately, to observation sentences that correspond to sensory, inputs; thus logical positivism combines rationalism and empiricism.3 The confirmation theory of Carnap and Carl Hempel (1905–1997) attempted to analyze the acquisition of knowledge from experience. Carnap’s book The Logical Structure of the World (1928) defined an, explicit computational procedure for extracting knowledge from elementary experiences. It, was probably the first theory of mind as a computational process., The Novum Organum is an update of Aristotle’s Organon, or instrument of thought. Thus Aristotle can be, seen as both an empiricist and a rationalist., 3 In this picture, all meaningful statements can be verified or falsified either by experimentation or by analysis, of the meaning of the words. Because this rules out most of metaphysics, as was the intention, logical positivism, was unpopular in some circles., 2

Page 26 :

Section 1.2., , The Foundations of Artificial Intelligence, , 7, , The final element in the philosophical picture of the mind is the connection between, knowledge and action. This question is vital to AI because intelligence requires action as well, as reasoning. Moreover, only by understanding how actions are justified can we understand, how to build an agent whose actions are justifiable (or rational). Aristotle argued (in De Motu, Animalium) that actions are justified by a logical connection between goals and knowledge of, the action’s outcome (the last part of this extract also appears on the front cover of this book,, in the original Greek):, But how does it happen that thinking is sometimes accompanied by action and sometimes, not, sometimes by motion, and sometimes not? It looks as if almost the same thing, happens as in the case of reasoning and making inferences about unchanging objects. But, in that case the end is a speculative proposition . . . whereas here the conclusion which, results from the two premises is an action. . . . I need covering; a cloak is a covering. I, need a cloak. What I need, I have to make; I need a cloak. I have to make a cloak. And, the conclusion, the “I have to make a cloak,” is an action., , In the Nicomachean Ethics (Book III. 3, 1112b), Aristotle further elaborates on this topic,, suggesting an algorithm:, We deliberate not about ends, but about means. For a doctor does not deliberate whether, he shall heal, nor an orator whether he shall persuade, . . . They assume the end and, consider how and by what means it is attained, and if it seems easily and best produced, thereby; while if it is achieved by one means only they consider how it will be achieved, by this and by what means this will be achieved, till they come to the first cause, . . . and, what is last in the order of analysis seems to be first in the order of becoming. And if we, come on an impossibility, we give up the search, e.g., if we need money and this cannot, be got; but if a thing appears possible we try to do it., , Aristotle’s algorithm was implemented 2300 years later by Newell and Simon in their GPS, program. We would now call it a regression planning system (see Chapter 10)., Goal-based analysis is useful, but does not say what to do when several actions will, achieve the goal or when no action will achieve it completely. Antoine Arnauld (1612–1694), correctly described a quantitative formula for deciding what action to take in cases like this, (see Chapter 16). John Stuart Mill’s (1806–1873) book Utilitarianism (Mill, 1863) promoted, the idea of rational decision criteria in all spheres of human activity. The more formal theory, of decisions is discussed in the following section., , 1.2.2 Mathematics, • What are the formal rules to draw valid conclusions?, • What can be computed?, • How do we reason with uncertain information?, Philosophers staked out some of the fundamental ideas of AI, but the leap to a formal science, required a level of mathematical formalization in three fundamental areas: logic, computation, and probability., The idea of formal logic can be traced back to the philosophers of ancient Greece, but, its mathematical development really began with the work of George Boole (1815–1864), who

Page 27 :

8, , ALGORITHM, , INCOMPLETENESS, THEOREM, , COMPUTABLE, , TRACTABILITY, , NP-COMPLETENESS, , Chapter 1., , Introduction, , worked out the details of propositional, or Boolean, logic (Boole, 1847). In 1879, Gottlob, Frege (1848–1925) extended Boole’s logic to include objects and relations, creating the firstorder logic that is used today.4 Alfred Tarski (1902–1983) introduced a theory of reference, that shows how to relate the objects in a logic to objects in the real world., The next step was to determine the limits of what could be done with logic and computation. The first nontrivial algorithm is thought to be Euclid’s algorithm for computing, greatest common divisors. The word algorithm (and the idea of studying them) comes from, al-Khowarazmi, a Persian mathematician of the 9th century, whose writings also introduced, Arabic numerals and algebra to Europe. Boole and others discussed algorithms for logical, deduction, and, by the late 19th century, efforts were under way to formalize general mathematical reasoning as logical deduction. In 1930, Kurt Gödel (1906–1978) showed that there, exists an effective procedure to prove any true statement in the first-order logic of Frege and, Russell, but that first-order logic could not capture the principle of mathematical induction, needed to characterize the natural numbers. In 1931, Gödel showed that limits on deduction do exist. His incompleteness theorem showed that in any formal theory as strong as, Peano arithmetic (the elementary theory of natural numbers), there are true statements that, are undecidable in the sense that they have no proof within the theory., This fundamental result can also be interpreted as showing that some functions on the, integers cannot be represented by an algorithm—that is, they cannot be computed. This, motivated Alan Turing (1912–1954) to try to characterize exactly which functions are computable—capable of being computed. This notion is actually slightly problematic because, the notion of a computation or effective procedure really cannot be given a formal definition., However, the Church–Turing thesis, which states that the Turing machine (Turing, 1936) is, capable of computing any computable function, is generally accepted as providing a sufficient, definition. Turing also showed that there were some functions that no Turing machine can, compute. For example, no machine can tell in general whether a given program will return, an answer on a given input or run forever., Although decidability and computability are important to an understanding of computation, the notion of tractability has had an even greater impact. Roughly speaking, a problem, is called intractable if the time required to solve instances of the problem grows exponentially, with the size of the instances. The distinction between polynomial and exponential growth, in complexity was first emphasized in the mid-1960s (Cobham, 1964; Edmonds, 1965). It is, important because exponential growth means that even moderately large instances cannot be, solved in any reasonable time. Therefore, one should strive to divide the overall problem of, generating intelligent behavior into tractable subproblems rather than intractable ones., How can one recognize an intractable problem? The theory of NP-completeness, pioneered by Steven Cook (1971) and Richard Karp (1972), provides a method. Cook and Karp, showed the existence of large classes of canonical combinatorial search and reasoning problems that are NP-complete. Any problem class to which the class of NP-complete problems, can be reduced is likely to be intractable. (Although it has not been proved that NP-complete, Frege’s proposed notation for first-order logic—an arcane combination of textual and geometric features—, never became popular., , 4

Page 28 :

Section 1.2., , PROBABILITY, , The Foundations of Artificial Intelligence, , 9, , problems are necessarily intractable, most theoreticians believe it.) These results contrast, with the optimism with which the popular press greeted the first computers—“Electronic, Super-Brains” that were “Faster than Einstein!” Despite the increasing speed of computers,, careful use of resources will characterize intelligent systems. Put crudely, the world is an, extremely large problem instance! Work in AI has helped explain why some instances of, NP-complete problems are hard, yet others are easy (Cheeseman et al., 1991)., Besides logic and computation, the third great contribution of mathematics to AI is the, theory of probability. The Italian Gerolamo Cardano (1501–1576) first framed the idea of, probability, describing it in terms of the possible outcomes of gambling events. In 1654,, Blaise Pascal (1623–1662), in a letter to Pierre Fermat (1601–1665), showed how to predict the future of an unfinished gambling game and assign average payoffs to the gamblers., Probability quickly became an invaluable part of all the quantitative sciences, helping to deal, with uncertain measurements and incomplete theories. James Bernoulli (1654–1705), Pierre, Laplace (1749–1827), and others advanced the theory and introduced new statistical methods. Thomas Bayes (1702–1761), who appears on the front cover of this book, proposed, a rule for updating probabilities in the light of new evidence. Bayes’ rule underlies most, modern approaches to uncertain reasoning in AI systems., , 1.2.3 Economics, • How should we make decisions so as to maximize payoff?, • How should we do this when others may not go along?, • How should we do this when the payoff may be far in the future?, , UTILITY, , DECISION THEORY, , GAME THEORY, , The science of economics got its start in 1776, when Scottish philosopher Adam Smith, (1723–1790) published An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations., While the ancient Greeks and others had made contributions to economic thought, Smith was, the first to treat it as a science, using the idea that economies can be thought of as consisting of individual agents maximizing their own economic well-being. Most people think of, economics as being about money, but economists will say that they are really studying how, people make choices that lead to preferred outcomes. When McDonald’s offers a hamburger, for a dollar, they are asserting that they would prefer the dollar and hoping that customers will, prefer the hamburger. The mathematical treatment of “preferred outcomes” or utility was, first formalized by Léon Walras (pronounced “Valrasse”) (1834-1910) and was improved by, Frank Ramsey (1931) and later by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern in their book, The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944)., Decision theory, which combines probability theory with utility theory, provides a formal and complete framework for decisions (economic or otherwise) made under uncertainty—, that is, in cases where probabilistic descriptions appropriately capture the decision maker’s, environment. This is suitable for “large” economies where each agent need pay no attention, to the actions of other agents as individuals. For “small” economies, the situation is much, more like a game: the actions of one player can significantly affect the utility of another, (either positively or negatively). Von Neumann and Morgenstern’s development of game, theory (see also Luce and Raiffa, 1957) included the surprising result that, for some games,

Page 29 :

10, , OPERATIONS, RESEARCH, , SATISFICING, , Chapter 1., , Introduction, , a rational agent should adopt policies that are (or least appear to be) randomized. Unlike decision theory, game theory does not offer an unambiguous prescription for selecting actions., For the most part, economists did not address the third question listed above, namely,, how to make rational decisions when payoffs from actions are not immediate but instead result from several actions taken in sequence. This topic was pursued in the field of operations, research, which emerged in World War II from efforts in Britain to optimize radar installations, and later found civilian applications in complex management decisions. The work of, Richard Bellman (1957) formalized a class of sequential decision problems called Markov, decision processes, which we study in Chapters 17 and 21., Work in economics and operations research has contributed much to our notion of rational agents, yet for many years AI research developed along entirely separate paths. One, reason was the apparent complexity of making rational decisions. The pioneering AI researcher Herbert Simon (1916–2001) won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1978 for his early, work showing that models based on satisficing—making decisions that are “good enough,”, rather than laboriously calculating an optimal decision—gave a better description of actual, human behavior (Simon, 1947). Since the 1990s, there has been a resurgence of interest in, decision-theoretic techniques for agent systems (Wellman, 1995)., , 1.2.4 Neuroscience, • How do brains process information?, NEUROSCIENCE, , NEURON, , Neuroscience is the study of the nervous system, particularly the brain. Although the exact, way in which the brain enables thought is one of the great mysteries of science, the fact that it, does enable thought has been appreciated for thousands of years because of the evidence that, strong blows to the head can lead to mental incapacitation. It has also long been known that, human brains are somehow different; in about 335 B . C . Aristotle wrote, “Of all the animals,, man has the largest brain in proportion to his size.” 5 Still, it was not until the middle of the, 18th century that the brain was widely recognized as the seat of consciousness. Before then,, candidate locations included the heart and the spleen., Paul Broca’s (1824–1880) study of aphasia (speech deficit) in brain-damaged patients, in 1861 demonstrated the existence of localized areas of the brain responsible for specific, cognitive functions. In particular, he showed that speech production was localized to the, portion of the left hemisphere now called Broca’s area. 6 By that time, it was known that, the brain consisted of nerve cells, or neurons, but it was not until 1873 that Camillo Golgi, (1843–1926) developed a staining technique allowing the observation of individual neurons, in the brain (see Figure 1.2). This technique was used by Santiago Ramon y Cajal (1852–, 1934) in his pioneering studies of the brain’s neuronal structures.7 Nicolas Rashevsky (1936,, 1938) was the first to apply mathematical models to the study of the nervous sytem., Since then, it has been discovered that the tree shrew (Scandentia) has a higher ratio of brain to body mass., Many cite Alexander Hood (1824) as a possible prior source., 7 Golgi persisted in his belief that the brain’s functions were carried out primarily in a continuous medium in, which neurons were embedded, whereas Cajal propounded the “neuronal doctrine.” The two shared the Nobel, prize in 1906 but gave mutually antagonistic acceptance speeches., 5, 6

Page 30 :

Section 1.2., , The Foundations of Artificial Intelligence, , 11, , Axonal arborization, Axon from another cell, Synapse, Dendrite, , Axon, , Nucleus, Synapses, Cell body or Soma, , Figure 1.2 The parts of a nerve cell or neuron. Each neuron consists of a cell body,, or soma, that contains a cell nucleus. Branching out from the cell body are a number of, fibers called dendrites and a single long fiber called the axon. The axon stretches out for a, long distance, much longer than the scale in this diagram indicates. Typically, an axon is, 1 cm long (100 times the diameter of the cell body), but can reach up to 1 meter. A neuron, makes connections with 10 to 100,000 other neurons at junctions called synapses. Signals are, propagated from neuron to neuron by a complicated electrochemical reaction. The signals, control brain activity in the short term and also enable long-term changes in the connectivity, of neurons. These mechanisms are thought to form the basis for learning in the brain. Most, information processing goes on in the cerebral cortex, the outer layer of the brain. The basic, organizational unit appears to be a column of tissue about 0.5 mm in diameter, containing, about 20,000 neurons and extending the full depth of the cortex about 4 mm in humans)., , We now have some data on the mapping between areas of the brain and the parts of the, body that they control or from which they receive sensory input. Such mappings are able to, change radically over the course of a few weeks, and some animals seem to have multiple, maps. Moreover, we do not fully understand how other areas can take over functions when, one area is damaged. There is almost no theory on how an individual memory is stored., The measurement of intact brain activity began in 1929 with the invention by Hans, Berger of the electroencephalograph (EEG). The recent development of functional magnetic, resonance imaging (fMRI) (Ogawa et al., 1990; Cabeza and Nyberg, 2001) is giving neuroscientists unprecedentedly detailed images of brain activity, enabling measurements that, correspond in interesting ways to ongoing cognitive processes. These are augmented by, advances in single-cell recording of neuron activity. Individual neurons can be stimulated, electrically, chemically, or even optically (Han and Boyden, 2007), allowing neuronal input–, output relationships to be mapped. Despite these advances, we are still a long way from, understanding how cognitive processes actually work., The truly amazing conclusion is that a collection of simple cells can lead to thought,, action, and consciousness or, in the pithy words of John Searle (1992), brains cause minds.

Page 31 :

12, , Chapter 1., Supercomputer, Computational units, Storage units, , Personal Computer, , 104 CPUs, 1012 transistors 4 CPUs, 109 transistors, 1014 bits RAM, 1011 bits RAM, 15, 10 bits disk, 1013 bits disk, Cycle time, 10−9 sec, 10−9 sec, 15, Operations/sec, 10, 1010, Memory updates/sec 1014, 1010, , Introduction, Human Brain, 1011 neurons, 1011 neurons, 1014 synapses, 10−3 sec, 1017, 1014, , Figure 1.3 A crude comparison of the raw computational resources available to the IBM, B LUE G ENE supercomputer, a typical personal computer of 2008, and the human brain. The, brain’s numbers are essentially fixed, whereas the supercomputer’s numbers have been increasing by a factor of 10 every 5 years or so, allowing it to achieve rough parity with the, brain. The personal computer lags behind on all metrics except cycle time., , SINGULARITY, , The only real alternative theory is mysticism: that minds operate in some mystical realm that, is beyond physical science., Brains and digital computers have somewhat different properties. Figure 1.3 shows that, computers have a cycle time that is a million times faster than a brain. The brain makes up, for that with far more storage and interconnection than even a high-end personal computer,, although the largest supercomputers have a capacity that is similar to the brain’s. (It should, be noted, however, that the brain does not seem to use all of its neurons simultaneously.), Futurists make much of these numbers, pointing to an approaching singularity at which, computers reach a superhuman level of performance (Vinge, 1993; Kurzweil, 2005), but the, raw comparisons are not especially informative. Even with a computer of virtually unlimited, capacity, we still would not know how to achieve the brain’s level of intelligence., , 1.2.5 Psychology, • How do humans and animals think and act?, , BEHAVIORISM, , The origins of scientific psychology are usually traced to the work of the German physicist Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894) and his student Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920)., Helmholtz applied the scientific method to the study of human vision, and his Handbook, of Physiological Optics is even now described as “the single most important treatise on the, physics and physiology of human vision” (Nalwa, 1993, p.15). In 1879, Wundt opened the, first laboratory of experimental psychology, at the University of Leipzig. Wundt insisted, on carefully controlled experiments in which his workers would perform a perceptual or associative task while introspecting on their thought processes. The careful controls went a, long way toward making psychology a science, but the subjective nature of the data made, it unlikely that an experimenter would ever disconfirm his or her own theories. Biologists, studying animal behavior, on the other hand, lacked introspective data and developed an objective methodology, as described by H. S. Jennings (1906) in his influential work Behavior of, the Lower Organisms. Applying this viewpoint to humans, the behaviorism movement, led, by John Watson (1878–1958), rejected any theory involving mental processes on the grounds

Page 32 :

Section 1.2., , COGNITIVE, PSYCHOLOGY, , The Foundations of Artificial Intelligence, , 13, , that introspection could not provide reliable evidence. Behaviorists insisted on studying only, objective measures of the percepts (or stimulus) given to an animal and its resulting actions, (or response). Behaviorism discovered a lot about rats and pigeons but had less success at, understanding humans., Cognitive psychology, which views the brain as an information-processing device,, can be traced back at least to the works of William James (1842–1910). Helmholtz also, insisted that perception involved a form of unconscious logical inference. The cognitive, viewpoint was largely eclipsed by behaviorism in the United States, but at Cambridge’s Applied Psychology Unit, directed by Frederic Bartlett (1886–1969), cognitive modeling was, able to flourish. The Nature of Explanation, by Bartlett’s student and successor Kenneth, Craik (1943), forcefully reestablished the legitimacy of such “mental” terms as beliefs and, goals, arguing that they are just as scientific as, say, using pressure and temperature to talk, about gases, despite their being made of molecules that have neither. Craik specified the, three key steps of a knowledge-based agent: (1) the stimulus must be translated into an internal representation, (2) the representation is manipulated by cognitive processes to derive new, internal representations, and (3) these are in turn retranslated back into action. He clearly, explained why this was a good design for an agent:, If the organism carries a “small-scale model” of external reality and of its own possible, actions within its head, it is able to try out various alternatives, conclude which is the best, of them, react to future situations before they arise, utilize the knowledge of past events, in dealing with the present and future, and in every way to react in a much fuller, safer,, and more competent manner to the emergencies which face it. (Craik, 1943), , After Craik’s death in a bicycle accident in 1945, his work was continued by Donald Broadbent, whose book Perception and Communication (1958) was one of the first works to model, psychological phenomena as information processing. Meanwhile, in the United States, the, development of computer modeling led to the creation of the field of cognitive science. The, field can be said to have started at a workshop in September 1956 at MIT. (We shall see that, this is just two months after the conference at which AI itself was “born.”) At the workshop,, George Miller presented The Magic Number Seven, Noam Chomsky presented Three Models, of Language, and Allen Newell and Herbert Simon presented The Logic Theory Machine., These three influential papers showed how computer models could be used to address the, psychology of memory, language, and logical thinking, respectively. It is now a common, (although far from universal) view among psychologists that “a cognitive theory should be, like a computer program” (Anderson, 1980); that is, it should describe a detailed informationprocessing mechanism whereby some cognitive function might be implemented., , 1.2.6 Computer engineering, • How can we build an efficient computer?, For artificial intelligence to succeed, we need two things: intelligence and an artifact. The, computer has been the artifact of choice. The modern digital electronic computer was invented independently and almost simultaneously by scientists in three countries embattled in

Page 33 :