Page 1 :

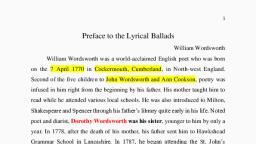

| “W2) Chapter 28 CRU, , Poetics, Literary Terms, , We AAU, , Literary terms are used in literature to define different kinds of, situations and actions. Aristotle uses a number of Greek terms in The, Poetics that have become a part of our literary lexicon. Genres are, categories into which kinds of literary material are organized., , Anagnorisis, , Anagnorisis is the recognition or discovery by the tragic hero of, some truth about his or her identity or actions that accompanies the, reversal of the situation in the plot. Oedipus’s realization that he is, in, fact, his father’s murderer and his mother’s lover is an example of, anagnorisis. There are four types of recognition - by signs, invented, at will, memory when an object awakens feeling and by process of, reasoning., , Antagonist, , In a drama or fiction a person who opposes a hero or a, protagonist., Antistrophe, , The second section of the chorus., , Apostrophe, Sudden turning away in speech to address someone., , Anthropomorphism, Concept of God having a human form., , Catastrophe, , Sudden accident or action that causes great and irreparable, suffering, e.g. murder of Desdemona by her husband Othello and his, , Own suicide at the climax.

Page 2 :

274 | POETICS Urdy, , Catharsis, , This word was normally used in ancient Greece by physicians, to mean “purgatian” or by priests to mean “purification.” In the, context of tragedy, Aristotle uses it to talk about a purgation or, purification of emotions of pity and fear that are aroused in the, viewers of a tragedy - pity of the hero’s plight, and fear that it will, , befall the viewers. It is a release of built up emotional energy, much, like a good cry, After catharsis, we reach a more stable and neutral, , emotional state., Character (Greek ‘Ethos’), , One of the six components of tragedy, character refers to the, human beings represented in the drama. Aristotle stresses that the, central aim of tragedy is not to depict human personalities, but rather, to represent human action. Character is second in importance to plot, for Aristotle; however, the character must be good, polite, true to life, and constant. Representation of character should always enhance the, , plot., , Classicism, , Classicism means to observe the style, rules, modes,, conventions, themes and sensibilities of the classical authors, like, Aristotle and Homer, etc., , Comedy, , Comedy presents human beings as “worse than they are” in, life, in order to present a different type of imitation than in a classical, tragedy. Aristotle notes that comic characters are not necessarily evil,, just ridiculous and laughable. He contrasts comedy with tragedy,, which represents humans as “better than they are.” Many scholars, speculate that Aristotle treated comedy in a lost section of the Poetics, or in another lost treatise., , Complex Plot, , A complex plot, in contrast to a simple plot, includes a reversal, of the dramatic situation (peripeteia) and/or recognition, (anagnorisis). Complex plots unfold through an internal logic and, causality; they are not simply strings of episodes., , Complication, , Complication is the rising action of a dramatic work that, extends from the beginning of the play to the climax or reversal.

Page 3 :

L, , 28 ~, POETICS: LITERARY TERMS o75, , Denouement, , Denouement is the unr, ; ‘ avelling of th, e . e plot and, complicat d mee that takes Place after the climax: Wt lechet of a, conclusion of the play. max; it leads to the, , Desis, , Literally “tying,” the desis is all, up to the climax. Plot threads are cra, more and more complex mess. At t, , these plot threads begin to unravel, denouement., , Deux Ex Machina, , the action in a tragedy leading, ftily woven together to form a, he peripeteia, or turning point,, in what is called the lusis, or, , Deux ex machina is the intervention of an unexpected or, invented character, device or event to resolve a plot. This term refers, to the intervention of a divinity in the action of a drama to resolve a, conflict and, often, to bring the action to a conclusion. Its literal, meanings are: “god from the machine.” In ancient stagecraft, an actor, playing the deity would be physically lowered by a crane-like, mechanism into the stage area. Sometimes this term is used to refer to, a miraculous (or just improbable) external influence that brings about, the resolution of a problem or conflict. Aristotle is disdainful of detwx, ex machina as a device to resolve plot situations in tragedy., , Diction (Greek “Lexis’), Diction is one of the six components of tragedy and it includes, how an actor delivers the lines written for him. Aristotle gives little, , attention to diction in Book XIX, suggesting that experts in the art of, oratory and the actors themselves are more responsible for the, , success of this dimension of tragedy than the poet., , Dionysus, Dionysus was the Greek god of wine and ecstasy, was, worshipped in festivals called Dionysia, which included, , performances of dithyrambic poetry, comedy, and tragedy. The, Greater Dionysia in Athens, established by the ruler Pisistratus, , around 534 BC, provided an occasion for performances of plays by all, the major ancient playwrights., , Dithyrambic Poetry, , The dithyramb was an ancient Greek hymn sung and danced in, honour of Dionysus, the god of wine and fertility; the term was also

Page 4 :

276 | PoRTICS Urdu, , used as an epithet of the god. The word dithyramb is of unknown but, probably non-Greek derivation. The form soon spread to other Greek, city-states, and dithyrambs were composed by the poets Simonides, and Bacchylides, as well as Pindar (the only one whose works have, survived in anything like their original form). According to Aristotle,, the dithyramb was the origin of Athenian tragedy. A wildly, enthusiastic speech or piece of writing is still occasionally described, as dithyrambic. One theory of the origin of Greek tragedy argues that, dithyrambic poetry was eventually coupled with a performance by a, single actor playing the role of a legendary hero, giving rise to the, basic structure of the tragedy. Plato also remarks in the Republic, (394c) that dithyrambs are the clearest example of poetry in which the, poet is the only speaker,, , Drama, , In the poetics, drama is contrasted with narrative in’ the, distinction between the epic and the tragedy. Through the speech and, gestures of actors, drama represents actions by placing them before, the audience's eyes., , Dramatic Irony, , Dramatic irony arises from the difference between what an, audience knows and what the character on the stage considers or, does. Being ignorant of his fate or circumstances, the character tries to, get rid of the trouble, but is entangled more and more into it because, of his doomed fate. His actions are ironic to an audience who knows, that the tragic outcome of the story cannot be avoided or his actions, are leading him to a disaster or bigger disaster., , Note the difference in examples for verbal and dramatic irony:, Antony calls Brutus “honourable” and knows he is not honourable,, while Othello calls lago “honest” and does not know of lago’s deceit., , Epic, , Epic is a long narrative poem, on a grand scale about the deeds, of warriors and heroes, e.g. Homer's epic ‘Iliad’ and ‘Odyssey’,, Spenser's ‘Faerie Queene’, Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’, etc. Epic presents, actions through narrative and is usually recited orally by a single, narrator. The meter proper to the epic is the hexameter. Aristotle, observes that the epic poet can either speak in his or her own words,, , or take on the voices of characters in order to advance the unfolding, of the plot.

Page 5 :

55 |, POETICS: LITERARY TERMS 1277, , gpode, It is the third section of the choral interlude, Fatalism |, , Fatalism means a_person’s fate, , unchangeable, so, the people should ac, showing doubts, reluctance and protest, avoid it., , is pre-determined and, cept their fate without, because there is no way to, , Fear, , Fear is one of the emotions aroused in the audience of a, tragedy. This fear results, Aristotle seems to suggest, when the, audience members understand that they, as human beings bound by, universal laws, are subject to the same fate that befalls the tragic hero., Fear, along with pity, is “purged” in the process of catharsis., , Hamartia, , The Greek word that describes what many people refer to as the, “tragic flaw” or “Error of Judgment” of the hero of Greek tragedy,, hamartia has a complex meaning which includes “sin,” “error,”, “trespass,” and “missing the mark”. This error need not be a moral, failing: it could be a simple matter of not knowing something or, forgetting something. The mistake of the hero that may arise from, ignorance or some moral shortcoming has an integral place in the plot, of the tragedy. The logic of the hero’s descent into misfortune is, determined by the nature of his or her particular kind of hamartia., According to Aristotle a tragic hero ought to be a man whose, misfortune comes to him, not through vice or depravity, but by, ‘hamartia’, e.g. Oedipus kills his father from impulse, and marries his, , mother out of ignorance., , Hellenism, Literary trend relating to Greek language and culture, usually, , of 4th to Ist century B.C., , Hexameter, sociated with Greek epic narrative,, , Th tic meter as, © Poene The feet are usually dactyls, , hexameter is based on a line with six feet., Or spondees; the last foot is a spondee.