Page 2 :

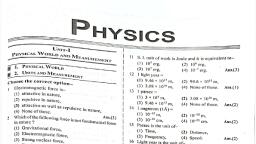

INDEX, , 1, , Physical World, , 1, , 2, , Units and Measurement, , 3, , 3, , Motion in A Straight Line, , 11, , 4, , Motion in A Plane, , 17, , 5, , Laws of Motion, , 24, , 6, , Work, Energy and Power, , 30, , 7, , Systems of Particles and Rotational Motion, , 36, , 8, , Gravitation, , 44, , 9, , Mechanical Properties of Solids, , 50, , 10, , Mechanical Properties of Fluids, , 54, , 11, , Thermal Properties of Matter, , 65, , 12, , Thermodynamics, , 71, , 13, , Kinetic Theory, , 79, , 14, , Oscillations, , 86, , 15, , Waves, , 92

Page 3 :

CHAPTER ONE, PHYSICAL WORLD, 1.1 INTRODUCTION, Science- Originates from the Latin word “scientia” meaning 'to know'., Physics – originates from the Greek word “Fusis” meaning nature. physics is the study of, the basic laws of nature and their manifestations., 1.2 BRANCHES OF PHYSICS, 1. Classical physics, 2. Modern physics, 1. Classical Physics, physics that was recognized and developed before the beginning of the 20 th century, Branch, Major focus, Classical mechanics, , The study of forces acting on bodies whether at rest or in, motion, , Thermodynamics, , The study of the relationship between heat and other forms, of energy, , Optics, , The study of light, , Electricity and magnetism, , The study of electricity and magnetism and their mutual, relationship, , 2.Modern Physics, Refers to the concepts in physics that have surfaced since the beginning of the 20 th century., Branch, Major focus, Quantum mechanics, , The study of the discrete nature of phenomena at the atomic, and subatomic levels, , Atomic physics, , The branch of physics which deals with the structure and, properties of the atom, , Nuclear physics, , The branch of physics which deals with the structure,, properties and reaction of the nuclei of atoms., , 1.3 FUNDAMENTAL FORCES IN NATURE, Name, , Relative, strength, , Range, , Operates among, , Gravitational force 10-39, , Infinite, , Weak nuclear force 10-13, , Very short, Sub-nuclear Some elementary particles,particularly, size, electron and neutrino, , All objects in the universe, , Electromagnetic, force, , 10-2, , Infinite, , Charged particle, , Strong nuclear, force, , 1, , Short, nuclear, size, , Nucleons, heavier elementary particles, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , 1, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 4 :

PREVIOUS QUESTIONS, 1.Which one of the following fundamental forces in nature binds Protons and neutrons, in a nucleus? ( IMP 2016), A) Gravitational force, B) Electromagnetic force, C) Strong nuclear force, D) Weak nuclear force, , (1), , 2. Which one of the following is present between all object in universe? (March 2016), A)Electromagnetic force, B)Magnetic Force, C)Gravitational force, D)Strong nuclear force, , (1), , 3.Choose the WRONG statement from the following statements. (IMP 2015), A)Electromagnetic force is the force between charged particles., B) Electrostatic force can be attractive or repulsive., C)Nuclear force binds protons and neutrons in a nucleus., D) Gravitational force is one of the strongest forces among fundamental forces in nature., , (1), , 4. Choose the correct answer from the bracket. Weakest force in nature is..................., (1), (Strong nuclear force, Electromagnetic force, Gravitational force, Weak nuclear force) (MAR 2015), 5. Pick the odd one out among the following forces, (MAR 2017), ( Gravitational force , Viscous force , Week nuclear force, Electromagnetic force ), , (1), , 6. The branch of physics that was developed to understand and improve the working of heat engine, is..........................., (MAR 2018), (1), (Optics , Thermodynamics ,electronics, Electrodynamics ), 7. The ratio of electrostatic force and the gravitational force between two protons kept fixed, distance is........................, (IMP 17), (1), -19, 19, 36, -36, ( 10 , 10 , 10 , 10 ), 8. The week nuclear force is stronger than gravitational force. State whether the statement is true or, false, (MAR 19), (1), , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , 2, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 5 :

CHAPTER 2, , UNITS AND MEASUREMENTS, 2.1 PHYSICAL QUANTITY, A quantity, which can be measured directly or, indirectly, is called a physical quantity., Ex : length, mass, time, speed, force, volume,, etc., 2.2 UNITS, measurement of a physical quantity involves, comparison with a reference standard. This, reference standard is called unit., Ex: metre is the unit of length, kilogram is the, unit of mass, second is the unit of time., , Thus in the measurement of a physical, quantity, two things are involved – a number, and a unit. The unit is the standard quantity, with which the measured quantity is compared, and the number shows how many times the, measured quantity is greater than the unit., A good unit will have the following, characteristics., It should be (a) well defined (b) internationally, acceptable (c) invariable (d) reproducible., 2.3 FUNDAMENTAL QUANTITIES AND, FUNDAMENTAL UNITS, A set of physical quantities which are, independent of each other are known as, fundamental quantities. The units of, fundamental quantities are called fundamental, units., 2.4 DERIVED QUANTITIES AND, DERIVED UNITS, Physical quantities, which can be expressed in, KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , 3, , terms of fundamental quantities, are called, derived quantities. The units of derived, quantities are called derived units., Eg: 1. Volume is measured in metre3 or m3 ., 2. Speed can be expressed in meter per, second (m/s), 2.5 SYSTEMS OF UNITS., A complete set of units for all physical, quantities with particular basic units is called a, system of units., The commonly used systems are:, (a) The FPS system: It is the British, Engineering system of units, which uses foot,, pound and second as the three basic units for, measuring length, mass and time respectively., (b) The c.g.s system: Which uses centimetre,, gram and second as the three basic units for, measuring length, mass and time respectively., (c) The MKS system:, (d) SI units(Metric System): In 1960,, International Committee for Weights Measures, adopted a system of units for all fundamental, physical quantities and is called International, system of units or SI units., In SI system, there are seven Fundamental, (basic) units and two Supplementary units., 2.6 FUNDAMENTAL QUANTITIES AND, THEIR UNITS IN SI SYSTEM, Fundamental quantity, , Unit, , Symbol, , Mass, , kilogram, , kg, , Length, , metre, , m, , Time, , second, , s, , Temperature, , kelvin, , K, , Electric current, , ampere, , A, , Luminous intensity, , candela, , cd, , Amount of substance mole, 2.7 SUPPLEMENTARY, AND THEIR UNITS, , mol, QUANTITIES, , Plane Angle, , radian, , rad, , Solid angle, , steradian, , sr, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 6 :

NOTE: These two quantities have units but no, dimension., Advantages of SI units:, 1) It is comprehensive., 2) The system is coherent., 3) It is internationally accepted., 2.8 DESCRIPTION OF PLANE ANGLE, (dθ ), , The Radian (rad): One radian is the angle, subtended at the centre of a circle by an arc, length equal to the radius of the circle., 2.9 DESCRIPTION OF SOLID ANGLE, (dΩ ), , The Steradian (sr): One steradian is the solid, angle subtended at the centre of a sphere by a, surface of the sphere, which is equal in area, to, the square of radius of the sphere ., Relations between radian , degree and, minute, 0, =>, π radian=180, 10= π radian, , multip prefix symbo submu Prefix symbo, le, l, ltiple, l, 101, , deca, , 10-1, , deci, , d, , 102, , hecto h, , 10-2, , centi, , c, , 103, , kilo, , 10-3, , milli, , m, , 106, , mega M, , 10-6, , micro μ, , 109, , giga, , 10-9, , nano, , n, p, , da, k, G, , 10, , 12, , -12, , terra, , T, , 10, , pico, , 1015, , peta, , P, , 10-15, , femto f, , 1018, , exa, , E, , 10-18, , atto, , 1021, , zetta, , Z, , 10-21, , zepto z, , 1024, , yotta, , Y, , 10-24, , yocto y, , a, , 2.10, MEASUREMENT, OF, BASIC, QUANTITES, 1.Measurement of Length, Distances ranging from 10 −5m to 10 2m can be, measured by direct methods., Eg: Metre Scale - To measure the distance, from 10−3 m to 1m, Vernier Calipers - up to 10−4 m, Screw Gauge - up to 10−5 m, The atomic and astronomical distances cannot, be measured by any of the above mentioned, direct methods., Measurement of large distances, Parallax method, Parallax is the name given to the apparent, change in the position of an object with, respect to the background, when the object is, seen from two different positions., See Fig., , 180, , ∠LOR is called the parallax angle, or parallactic angle., , 10= 60' (minute of arc), 1'(minute of arc) = 60'' (seconds of arc), , Taking LR as an arc of length b and, radius LO = RO = x, , 2.10 MULTIPLES AND SUB MULTIPLES, OF UNITS., , we get, , To express magnitude of physical quantities,, which are very large or small, we use prefixes, to the unit., KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , 4, , θ=, , b, x, , where b-basis ,, , x-unknown distance., Knowing ‘b’ and measuring θ, we can, @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 7 :

calculate x., * HW: Example 2.2, 2.3, 2.4, 2.Measurement of Mass, Common objects - Common balance or spring, balance or electronic balance, Larger masses like that of planets, stars etc Gravitational methods, Small masses like atomic/subatomic particles, etc - Mass spectrograph., 3.Measurement of time, A clock is used to measure the time interval., An atomic standard of time, is based on the, periodic vibration produced in a Cesium atom., 6.11 THEORY OF ERRORS, The result obtained from any measurement, will contain some uncertainty. Such an, uncertainty is termed error., Accuracy And Precesion, Accuracy is a measure of how close the, measured value is to the true value of the, quantity., Precision refers to the closeness of two or, more measurements to each other., , Errors in Measurement, 1.Systematic error, 2. Random error ., 1.Systematic Errors:, The systematic errors are those errors that end, to be in one direction, either positive or, negative. Systematic errors can be classified as, follows., (a). Instrumental Error : These errors are due, to the defect of the instrument., Eg: 1. Zero error in screw gauge and vernier., 2.Faulty calibration of thermometer, metre, scale etc., (b). Error due to Imperfection : This is due to, KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , 5, , imperfection of the experimental procedure., Eg: A thermometer placed under the armpit, will always give a temperature lower than the, actual value of the body temperature., (c). Personal Error : This is due to the mode of, observation of the person taking the reading ., Eg: Parallax error., (d). Errors due to external causes : The change, in the external conditions during an, experiment can cause error in measurement., Eg: changes in temperature,or pressure during, measurements may affect the result of the, measurement., (e). Least Count Error : LC is the smallest, value that can be measured by the measuring, instrument, and the error due to this, measurement is least count error. The, instrument’s resolution hence is, the cause of this error. Least count error can be, reduced by using a high precision instrument, for the, measurement., 2. Random Error :, The random errors are those errors, which, occur irregularly and hence are random with, respect to sign and size., Eg:, 1.unpredictable, fluctuations, in, temperature, voltage supply etc become source, of error 2. when the same person repeats the, same observation, it is very likely that he may, get different readings every time., ERROR ANALYSIS, 1. Absolute Error, The magnitude of difference between the true, value and the measured value of a quantity is, called absolute error. If a1 , a2 , a3 , ..........an, are the measured values of any quantity ‘a’ in, an experiment performed n times, then the, arithmetic mean of these values is called the, true value (am ) of the quantity. Ie,, am =, , a1 +a2 +a 3+............. a n, n, , The absolute error in measured values is given, by, |Δ a1|=|am−a1|, |Δ a2|=|am−a2|, @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 8 :

Similarly, , two decimal place, (ii) Absolute error , |ΔT|=|T m−t|, , |Δ an|=|am −an|, , 2. Mean Absolute error ( |Δ am| ), The arithmetic mean of absolute errors, in all the measurements is called the mean, absolute error. Ie,, Δ a m=, , |Δ T 1|=|2.62−2.63|=0.01, |Δ T 2|=|2.62−2.56|=0.06, |Δ T 3|=|2.62−2.42|=0.20, |Δ T 4|=|2.62−2.71|=0.09, |Δ T 5|=|2.62−2.80|=0.18, , |Δ a1|+|Δ a2|+|Δ a3|+..............+|Δ an|, n, , (iii) Mean absolute error,, , 3. Relative Error, Relative error =, , |Δ T m|=, , Mean absolute error, Mean value, , = 0.11 s ( Rounded off to two decimal, places), , Eg: A driver’s speedometer shows that his car, is travelling at 60 km/h when it is actually, moving at 62 km/h. Then absolute error of, speedometer is 62 km/h-60 km/h= 2 km/h., Relative error of the measurement is, 2 km/ h, =0.322 km/h, 62 km/h, , (iv) Relative error,, Relative error =, , =, , =4%, (vi) Time period of simple pendulum,, T =(2.62±0.11)s, , NOTE: If we do a single measurement, the, value we get may be in the range am ± ∆am, Problem 1: In a series of successive, measurements in an experiment, the readings, of the period of oscillation of a simple, pendulum were found to be 2.63s, 2.56 s,, 2.42s, 2.71s and 2.80s. Calculate (i) the mean, value of the period of oscillation (ii) the, absolute error in each measurement (iii) the, mean absolute error (iv) the relative error, (v)the percentage error. Express the result in, proper form., Solution, , =>, , 0.11, =0.0419=0.04, 2.62, , P . E=R . E x 100=0.04 x 100, , |Δ am|, Percentage error =, x 100, am, , =>, , Mean absolute error, Mean value, , (v) Percentage error ,, , 4. Percentage Error, , (i), , 0.01+ 0.06+0.20+ 0.09+ 0.18, =0.108 s, 5, , t 1 +t 2+t 3 +t 4 +t 5, 5, 2.63+2.56+2.42+2.71+2.80, T m=, 5, T m=2.624 s = 2.62 s (Rounded off to, T m=, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , 6, , COMBINATION OF ERRORS, The error in the final result depends on, (i) The errors in the individual measurements, (ii) On the nature of mathematical operations, performed to get the final result. So we should, know the rules to combine the errors., (a) Error of a sum or a difference, *Let ΔA and ΔB be the absolute errors in the, two quantities A and B respectively. Then,, Measured value of A = A ± ΔA, Measured value of B = B ± ΔB, Consider the sum, Z = A + B, The error ΔZ in Z is then given by, Z ±Δ Z=( A±Δ A)+(B±Δ B), = ( A+ B)±( Δ A + Δ B), = Z ±( Δ A +Δ B), , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 9 :

=>, , Δ Z=(Δ A +Δ B), , We will get the same result even if we take the, difference. Ie,, The maximum possible error in the sum of, two quantities or difference of two, quantities is equal to the sum of the, absolute errors in the individual quantities., Examples, 1)Two resistances R1 = (100 ± 3) Ω and R2 =, (150 ± 2) Ω are connected in series. What, is, their, equivalent, resistance?, Soln: (250 ± 5) Ω, 2) Do example 2.8 NCERT, (b) Error of a product or a quotient, Let ΔA and ΔB be the absolute errors in the, two quantities, A and B, respectively. Then,, Measured value of A = A ± ΔA, Measured value of B = B ± ΔB, Consider the product , Z = A B, , As, their, , product, , are both small quantities,, term, , ΔA ΔB, A B, , can, , We know, , Δ A Δl Δb, = +, A, l, b, , =>, , Δ A=A, , =>, , ( Δl l + Δbb ), 0.1 0.2, Δ A=19.4 (, +, 5.7 3.4 ), = 1.48 = 1.5, , Therefore , Area with error limit,, 2, , A=(19.4±1.5)cm, , (c) Error in the power of a quantity, , ΔZ, ΔB Δ A Δ A Δ B, =1±, ±, ±, Z, B, A, A B, ΔB, ΔA, ,, B, A, , Area with error limit = A ± ΔA = ?, Area A = l × b = 5.7 × 3.4, = 19.38 = 19.4 cm 2, , 2) Do Example 2.9 NCERT, 3) Example 2.10 NCERT [HW], 4) The voltage across a wire is (100 ± 5)V and, the current passing through it is (10±0.2) A., Find the resistance of the wire. [HW], , The error ΔZ in Z is given by, Z ± ΔZ = (A ± ΔA) (B ± ΔB), The error ΔZ in Z is given by, Z ± ΔZ =(A ± ΔA) (B ± ΔB), = (AB) ± (A ΔB) ± (B ΔA) ± (ΔA . ΔB), Dividing L.H.S by Z and R.H.S by AB,, we get,, 1±, , Examples, 1)The length and breadth of a rectangle are, (5.7 ± 0 . 1 ) cm and (3.4 ± 0 . 2 ) cm, respectively. Calculate the area of the, rectangle with error limits., Soln) Length l= (5.7 ± 0 . 1 ) cm ,, Breadth b =(3.4 ± 0 . 2 ) cm, , be, , neglected., So the maximum relative error in Z is ,, , The relative error in a physical quantity, raised to the power k is the k times the, relative error in the individual quantity., Examples, 1) Find the relative error in Z, if, Z = A 4 B 1/3 /CD 3/2 ., Solution, , ΔZ, Δ A 1 Δ B ΔC 3 Δ D, =4, +, +, +, Z, A 3 B, C 2 D, , ΔZ Δ A ΔB, =, +, Z, A, B, , 2) Example 2.12 NCERT [HW], , This is true for division also. Ie,, The maximum fractional error in the, product of two quantities or quotient of, two quantities is equal tothe sum of the, fractional errors in the individual, quantities., , SIGNIFICANT FIGURES, The digits that are known reliably plus the first, uncertain digit are known as significant figures, or significant digits., , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , 7, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 10 :

RULES FOR COUNTING THE NUMBER, OF SIGNIFICANT FIGURES, 1) All non-zero digits are significant, Ex: 1342 has 4 significant figures, 2) All zeros between two non-zero digits are, significant, no matter where the decimal, point is., Ex: 1002 has 4 significant figures, 20.003 has 5 significant figures, 3) If the number is less than 1, the zero (s), on the right of the decimal point but to left, of the first non zero digit are not significant., Ex: 0.00345 has 3 significant figures, 4) The terminal or trailing zero(s) in a, number without a decimal point are not, significant., Ex: 123 m = 12300 cm = 123000 mm, has three significant figures, 5) The trailing zero(s) in a number with a, decimal point are significant., Ex: 3.500 has 4 significant figures, 0.06900 has 4 significant figures, 6) The number of significant figures does, not depend on the system of units used, Ex:123 m = 12300 cm = 123000 mm, has three significant figures, 7) The power of 10 is irrelevant to the, determination of significant figures., Ex: = 5.70 m = 5.70 × 102 cm =, 5.70 × 10 3 mm = 5.70 × 10 −3 km have 3, significant figures ., RULES FOR ROUNDING OFF, 1) If the digit to be dropped is smaller than, 5, then the preceding digit should be left, unchanged., i) 7.32 is rounded off to 7.3, , increased by 1, i) 17.26 is rounded off to 17.3, ii) 11.89 is rounded off to 11.9, 3) If the digit to be dropped is 5 followed by, digits other than zero, then the preceding digit, should be raised by 1, , i)7.352 is rounded off to 7.4, ii)18.159 is rounded off to 18.2, 4) If the digit to be dropped is 5 or 5, followed by zeros, then the preceding digit, is not changed if it is even, i) 3.45 is rounded off to 3.4, ii) 8.250 is rounded off to 8.2, 5)If the digit to be dropped is 5 or 5, followed by zeros, then the preceding digit, is raised by 1 if it is odd, i) 3.35 is rounded off to 3.4, ii) 8.350 is rounded off to 8.4, RULES FOR ARITHMETIC, OPERATIONS WITH SIGNIFICANT, FIGURES., 1) In addition and subtraction, the final result, should retain as many decimal places as there, are in the number with the smallest number of, decimal, , places., 1)3.1 + 1.780 + 2.046 = 6.926, Here the least number of significant, digits after the decimal is one. Hence the, result will be 6.9., 2)12.637 – 2.42 = 10.217 Hence the, , result will be 10.22, 2) In multiplication or division, the final, result should retain as many significant, figures as there are in the original number, with smallest number of significant figures., 1) 1.21 × 36.72 = 44.4312 = 44.4, 2) 36.72 ÷ 1.2 = 30.6 = 31, DIMENSION OF PHYSICAL, QUANTITIES, , ii) 8.94 is rounded off to 8.9, 2) If the digit to be dropped is greater than, 5, then the preceding digit should be, , Dimensions of a physical quantity are the, powers to which the fundamental units be, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , 8, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 11 :

raised in order to represent that quantity., Eg: Velocity=, , ,where m is the mass of the body, v its, velocity, g is the acceleration due to gravity, and h is the height. Check whether this, equation is dimensionally correct., , Displacement [ L], 0, −1, =, =[ M L T ], time, [T ], , Hence the dimensions of velocity is 0 in mass,, 1 in length and -1 in time., Problem: ( Do yourself), Find the dimensional formula of the following, physical quantities., (a) Acceleration (b) Force (c) Momentum, (d) Kinetic energy (e) Mass per unit length, , Solution, , DIMENSIONAL FORMULA AND, EQUATION, , Since both term has the same dimension , the, given equation is dimensionally correct., , Dimensional formula is an expression which, shows how and which of the fundamental units, are required to represent the unit of a physical, quantity., Eg: [M 0 LT −2 ] is the dimensional formula of, acceleration., , Eg: Do Examples 2.16 NCERT, , When the dimensional formula of a physical, quantity is expressed in the form of an, equation, such an equation is known as the, dimensional equation., Eg: Acceleration = [M 0 LT −2 ]., Principle of homogeneity of dimensions, The principle of homogeneity of dimensions, states that the dimensions of all the terms in, a physical expression should be the same., Eg: v 2 = u 2 +2as , the dimensions of v 2 , u 2, and 2as have the same dimension [L 2 T −2 ]., APPLICATIONS OF DIMENSIONAL, ANALYSIS, 1.To check the correctness of an equation, Checking the correctness of the equation using, principle of homogeneity., Here we use the principle of homogeneity to, check the correctness of the equation, Problem:, Let us consider an equation, , 1, m v 2=mgh, 2, , The dimension of, , = [M L2 T-2], The dimension of mgh = [M][LT-2][L], = [M L2 T-2], , 2.To establish the relation among various, physical quantities, Problem, Consider a simple pendulum, having a bob, attached to a string, that oscillates under the, action of the force of gravity. Suppose that the, period of oscillation of the simple pendulum, depends on its length (l), mass of the bob (m), and acceleration due to gravity (g). Derive the, expression for its time period using method of, dimensions., Solution, *The dependence of time period T on the, quantities l, g and m as a product may be, written as :, T=klxgymz, where k is dimensionless constant and x, y, and z are the exponents., By considering dimensions on both sides, we, have, [M o L o T 1 ]=[L 1 ]x [L 1 T –2 ]y [M 1 ]z, = L x+y T –2y M z, On equating the dimensions on both sides,, we have, x + y = 0; –2y = 1; and z = 0, So x=, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , 9, , 1, 2, m v = [M][LT-1]2, 2, , @, , 1, ,, 2, , y=, , −1, ,, 2, , z=0, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 12 :

Then, T =k l1/ 2 g−1 /2, , => T =k, , Actually, k = 2π =>, , √, , (a) 3215, (e) 3100, , l, g, , T =2 π, , √, , (b) 11.01, (f) 007, , (c) 0.003 (d) 1.000, , 6. Report the result of the following with, correct significant figures, , l, g, , Limitations of Dimensional Analysis., 1) This method gives us no information about, dimensionless constants., 2) We cannot use this method if the physical, quantity depends on more than three other, physical quantities., 3) This method cannot be used if the left hand, side of the equation contains more than one, term., 4) Often it is difficult to guess the parameters, on which the physical quantity depends., , (a) 30.1 + 2.760 + 9.046, (c) 1.21 × 36.72, , 7. If the velocity of sound through a medium, depends on the bulk modulus , 'B' of the, medium and density, 'ρ' of the medium , obtain, the relation connecting the velocity of sound,, bulk modulus and the density of the medium., (Given that the bulk modulus has the, dimension of force per area), 8. “ A dimensionally correct equation may not, be a physically correct equation” . Comment, the statement., , ADDITIONAL QUESTIONS, 1 . a) A boy recalls the relativistic mass, wrongly, , as, , m=, , m0, , √(1−V 2 ), , ., , Using, , dimensional method put the missing ‘C’ at the, proper place., b) Name and state the principle used in solving, the above problem., [ imp. 2012], 2. If the percentage error in calculating the, radius of the sphere is 2% , what will be the, percentage error in calculating the volume?, [imp 2013], 3. Which of the following measurement is, more accurate? Why?, i. 500.00kg., ii. 0.0005kg., iii.6.00kg., , √, , 4. Check whether the equation T =2 π m is, g, , dimensionally correct. Where,, T - > Time period of a simple Pendulum., m - > mass of the bob., g -> acceleration due to gravity., , 5 . Find out the number of significant figures, in the followig, KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , 10, , (b) 12.637 – 2.42, (d) 36.72 ÷ 1.2, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 13 :

CHAPTER THREE, MOTION IN A STRAIGHT LINE, 3.1 INTRODUCTION, Point object : If the size of the object is much smaller than the distance it moves in a reasonable, duration of time, then the object is said to be point object., Reference point : In order to specify the position of an object, we need to use a reference point, and a set of axes. For convenience we use a rectangular coordinate system consisting three, mutually perpendicular axes (X,Y,Z) as set of axes and the point of intersection of these three, axes (origin ) as the reference point., 3.2 POSITION, PATH LENGTH AND DISPLACEMENT, , 3.2.1 Position, To specify position we fix a origin (O). Positions to the right of O are taken as positive and, to the left of O, as negative ( convention), Thus the position co ordinates of P ,Q , R are +360 m , +240 m , -120 m respectively., 3.2.2 Path length (Distance), It is the total distance covered., Suppose a car moves from O to P and then moves back from P to Q , then the total path length, (distance) covered = OP+PQ = 360 m+120 m= 480 m, 3.2.3 Displacement (Δx), It is the shortest distance between the final and initial positions, Suppose a car moves from O to P and then moves back from P to Q , then Δx = xQ-xO = + 240 m, If a car moves from O to P and then moves back from P to R , then Δx = xR-xO = -120 m, If a car moves from O to P and then moves back from P to O , then Δx = xO-xO = 0, NOTE:, * Distance is a scalar quantity ( only magnitude , no direction) while displacement is a vector, quantity ( it has both magnitude and direction), * Distance can only have positive values while Displacement can be positive, negative and even, zero., * The magnitude of displacement may or may not be equal to the path length traversed by an, object., Problem 1, A point P is the contact point of a wheel on ground which rolls on, ground without slipping. What is the displacement of the point P, when wheel completes half of rotation (if radius of wheels is 1m), Solution, , Displacement , S =, , √(π R)2 +( 2 R)2, , Since R=1 m,, , S=, , √ π2 + 4, , = R √ π2 +4, , m, , Motion: If a body changes its position with time , then the body is said to be in motion., , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , @, 11, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 14 :

3.3 SPEED AND VELOCITY, 3.3.1 Average speed, The average speed is defined as the ratio of the total path length covered by the particle to the total, time taken, , Average speed=, , total path length, Total time interval, , NOTE, * If a particle travels distances S 1 , S2 , S 3 with speeds v 1 , v 2 , v 3 respectively in same direction ., Then,, Total distance travelled=S1 +S 2 +S 3, , Therefore ,, , ,, , Total time taken=, , The average speed =, , S1 S2 S3, + +, v 1 v 2 v3, , S1 + S2 + S3, S1 S2 S3, + +, v1 v2 v3, , * If a particle travels with speeds v 1 , v 2 , v 3 during the time interval t1 , t2 , t 3 respectively., Total time taken=t 1+ t 2 +t 3, Then, Total distance travelled=v1 t 1 + v 2 t 2+ v 3 t3 ,, Therefore ,, , The average speed=, , v 1 t 1 +v 2 t 2+v 3 t 3, t 1+ t 2 +t 3, , 3.3.2 Average velocity, It is the ratio of displacement to the time taken, The average velocity=, , Δ x x 2−x 1, =, Δ t t 2−t 1, , 3.3.3 Instantaneous velocity (Velocity), The time rate of change of position with time at any instant is called Instantaneous velocity, Uniform motion (Uniform velocity), If a body covers equal displacement in equal interval of time , then the body is said to be in, uniform motion. During uniform motion magnitude and direction of the velocity remains constant., Non uniform velocity, If a body covers unequal displacements in equal interval of time or equal displacements in unequal, interval of time, then the body is said to be in non uniform motion. During non uniform motion, either magnitude or direction of the velocity changes., 3.4 Position – time graph, NOTE: The slope of position, time graph (Δx/Δt) gives the, velocity. In Fig, (a) Slope = (x2-x1)/(t2-t1) = 0, (b)Slope =(x2-x1)/(t2-t1) = +ve, (c) Slope =(x2-x1)/(t2-t1) = -ve, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , @, 12, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 15 :

3.5 Velocity - time graph for uniform motion., NOTE :, Area under the velocity - time graph is equal, the displacement of the particle., Here the displacement covered by the particle, between 6s and 12s is 40 x 6 = 240m, , 3.6 Acceleration, The rate of change of velocity of an object is called acceleration., Or, , a=, , V −u, t, , NOTE:If an object is slowing down, then its acceleration is in the opposite direction of its, velocity. When an object is speeding up, the acceleration is in the same direction of the velocity., Ex : Raju throws a stone up and it comes back. Give sign for displacement, velocity and, acceleration during its (a) Upward motion (b) Downward motion, soln: I fix upward direction as positive and downward direction as negative ( Reverse can be, taken), (a) Upward motion: displacement= positive , velocity= positive, acceleration = negative ( during, upward motion body slows down , so acceleration is in the opposite direction of velocity), (b) Downward motion: displacement= negative , velocity= negative, acceleration = negative, ( during downward motion body speeds up , so acceleration is in the same direction of velocity), Instantaneous acceleration, , 3.6.1 Uniform acceleration, If the velocity of an object changes by equal amounts in equal intervals of time (however small the, intervals may be) , then the body is in uniform acceleration., Eg: A freely falling stone has an acceleration 9.8 m/s2 means velocity of the stone increases 9.8m/s, in each second., 3.6.2 Position-time graph for uniformly accelerated motion, Fig(a):Uniform acceleration, ( Note the slope of x-t graph, is increasing ,velocity, increases), , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , Fig(b):Uniform deceleration, ( Note the slope of x-t graph is, decreasing ,velocity decreases), , @, 13, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 16 :

3.6.3 Velocity-time graph for uniformly accelerated motion, Fig(a) Motion in positive, direction with positive, acceleration, , Fig(b) Motion in positive, direction with, negative acceleration, , Fig(c) Motion in negative, direction with negative, acceleration, , Fig(d) Motion of an, object with negative, acceleration that changes, its direction at time t1 ., , NOTE : 1) The slope of velocity time graph gives acceleration, 2)Area under the velocity time graph gives the displacement, 3.7 KINEMATIC EQUATIONS FOR UNIFORMLY ACCELERATED MOTION, Let, u- Initial velocity, v- Final velocity after time t, s- displacement covered in time t, a- Uniform acceleration, First Equation Of Motion, Acceleration = Slope of velocity-time graph, v−u, t, v −u=at, v =u+a t, a=, , =>, =>, ........................ (1), This is the first equation of motion., , Second Equation Of Motion, Displacement = Area under the velocity-time graph, => S= Area of Δ ABC + Area of □ ACOt, , 1, 2, v, =u+a, t in (2), Substitute, (2) => S=ut +1/2(u+at−u) t, 1, => S=ut + a t 2 .....................(3), 2, , => S= (v−u) t+ ut ....................(2), , (OR), , 1, S= (u+v )t, 2, , This is the second equation of motion, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , @, 14, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 17 :

Third equation of motion, From (1) v =u+a t, Squaring both sides , we get v 2=(u+ at )2=u2 +2u at +(a t )2, 1, 2, , = u2 +2 a(ut + a t 2 ), 2, , =>, , 2, , ................(4), This is the third equation of motion, v =u + 2 aS, , Summary, 1 2, S=ut + a t, 2, , v =u+a t, , 2, , 2, , v =u + 2aS, , 1, S= (u+v )t, 2, , Stopping distance of vehicles, When brakes are applied to a moving vehicle, the distance it travels before stopping is called, stopping distance. It is an important factor for road safety and depends on the initial velocity (u), and the braking capacity, or deceleration, –a that is caused by the braking., Expression for stopping distance, Let the distance travelled by the vehicle before it stops be d s ., Then, using equation of motion v 2=u 2+ 2 aS and noting that v = 0, S= d s , the equation, becomes,, 0=u2+ 2 a d s => −u 2=+2 a d s, ie, the stopping distance, , ds =, , −u2, 2a, , Thus, the stopping distance is proportional to the square of the initial velocity. Doubling the initial, velocity increases the stopping distance by a factor of 4 (for the same deceleration)., 3.8 RELATIVE MOTION, Consider two objects A and B moving uniformly with velocities v A and v B in one, dimension(along x-axis) with respect to the ground . If x A (0) and x B (0) are positions of objects A, and B, respectively at time t = 0, their positions x A (t) and x B (t) at time t are given by:, Then, the displacement from object A to object, B is given by, ...........................(5), (5) => Final distance between objects=initial distance between objects+ Relative velocity x time interval ., = vBA is the velocity of object B relative to object A . ie, relative velocity of B wrto A., Similarly (vA – vB) = vAB is the velocity of object A relative to object B . ie, relative velocity of A, wrto B., Special cases, Case 1: when vA= vB from (4) xBA(t)= xB(0) – xA(0), i.e. the distance between the two objects remains the same at all times., The position time graph for such motion is as shown in fig., , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , @, 15, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 18 :

Case 2: when v A > v B ( v A and v B in the same direction), v B - v A is -ve., From (4), we get x B (t) - x A (t) < x B (0) - x A (0), ie, the value of x B (t) - x A (t) first decreases, becomes zero, and then increases in magnitude. The position time graph for such, motion is as shown in fig., Case 3: when v A < v B ( v A and v B in the same direction), v B - v A is +ve., From (4), we get x B (t) - x A (t) > x B (0) - x A (0), ie, the value of x B (t) - x A (t) increase as time passes. The position time, graph. for such motion is as shown in fig., Case 4 : When v A and v B are in opposite directions ( say v A in +ve X, direction and v B in the -ve X direction) .The position time graph, for such motion is as shown in fig., , Do Example 3.1, 3.4, 3.6, 3.8 ,3.9, , Previous Questions, 1.Velocity is defined as the rate of change of displacement., a) Distinguish between average velocity and instantaneous velocity., b) When does the average velocity becomes equal to the instantaneous velocity?, c) A car travels from A to B at 60 km/hr and returns to A at 90 km/hr. What is its average velocity, and Average speed?, .............................................................................................................................................................., 2. The figure shows the position – time, graph of a body moving along a straight line., a)Draw the velocity-time graph of the body., From the graph, b) find the displacement in 20 seconds., .............................................................................................................................................................., 3.Acceleration – time graph of a body starts from rest as shown below:, ( a in m/s2 and t in seconds), a) Draw the velocity – time graph using the above graph., b) Find the displacement in the given interval of time from 0 to 30 seconds., , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , @, 16, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 19 :

CHAPTER FOUR, , (Note that v1≠ 2 v2 but the magnitude of v1 is, equal to 2 x magnitude of v2), , MOTION IN A PLANE, 4.1 INTRODUCTION, In order to describe motion of an object in two, dimensions (a plane) or three dimensions, (space), we need to use vectors., Example for motion in a plane, Motion of a coin on a carom board,An insect, crawling over the floor of a room, projectile, motion, etc., 4.2 ELEMENTARY CONCEPTS OF, VECTOR ALGEBRA, Scalar quantity and vector quantity, Scalar quantity: A quantity with magnitude, only. It is specified completely by a single, number, along with the proper unit., Eg : mass, temperature , distance, The rules for combining scalars are the rules of, ordinary algebra., Vector quantity: A quantity that has both, magnitude and direction and obeys vector, algebra . It is specified by giving its magnitude, by a number and its direction., Eg: displacement, velocity, acceleration , force, Representation of vectors, 1. Geometrical (Graphical ) representation, 2. Analytical representation, Geometrical representation of vectors, A vector represented by an arrow. Length of the, arrow indicates its magnitude and arrow head, indicates its direction, , 4.2.1 TYPES OF VECTORS, 1.Equal vectors: Two vectors A and B are said, to be equal when they have, equal magnitude and same, direction and represent the, same physical quantity., 2. Collinear vectors: Those vectors which act, along the same line. The angle between them, can be 0° or 180°., 3.Parallel Vectors: If two vectors A and B act, in the same direction along the same line or on, parallel lines( the angle between them is 00), , 4.Anti–parallel vectors: Two vectors A and B, are said to be anti–parallel when they are in, opposite directions along the same line or on, parallel lines (the angle between them is 180 0), , 5.Unit vector: A vector divided by its, magnitude is a unit vector. The unit vector for, A is denoted by  ( A cap). It has a magnitude, equal to unity or one., , The given vector is toward east direction, 6.Orthogonal unit vectors:, Let i , j , k be three unit, vectors which specify the, directions along positive x–, axis, positive y–axis and, positive z–axis respectively., These three unit vectors are, directed perpendicular to each, other., These three vectors are orthogonal unit vectors., , F1 = 3 N towards east, F2 = 6 N towards east, ( Note that F2=2 F1), , v1= 10 m/s towards north, v2= 5 m/s towards north, east, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 17, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 20 :

4.2.2 MULTIPLICATION OF VECTORS, BY REAL NUMBERS, Multiplying a vector A with a positive number, λ gives a vector whose magnitude is changed, by the factor λ but the direction is the same as, that of A, Step1: Two vectors A and B with their tails, brought to a common origin. (Fig. a), Step 2: The sum R= A + B is obtained using, the parallelogram method . (Fig b), , Fig (a) : Vector A and the resultant vector after, multiplying A by a positive number 2., Fig (b) : Vector A and resultant vectors after, multiplying it by a negative number –1and –1.5., , NOTE, The parallelogram, method of vector, addition is equivalent, to the triangular, method. (Fig. c), 4.2.4 SUBTRACTION OF VECTORS, , 4.2.3 ADDITION OF VECTORS, (Geometrical method), (1) Triangular law of addition method (HT ), (2) Parallelogram law of addition method (TT), (1)Triangular Law of addition method, The, tail, of, the, , Fig a: Two vectors A and B , – B is also shown., Fig, b:, , second vector B is connected to the head of the, first vector A . Then the resultant is the vector, connecting the tail of the first vector A to the, head of the second vector B., , Subtracting vector B from vector A, (R 2= A-B) . For comparison, addition of, vectors A and B ( R 1= A+B) is also shown., NOTE, A+B=B+A ( Commutative), (A+B)+C=A+(B+C) (Associative), (2) Parallelogram law of addition method, , Magnitude and direction of the resultant of, two vectors A and B in terms of their, magnitudes and angle θ between them, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 18, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 21 :

In 2D , a vector A can be represented as, ⃗, A = A x ^i+ A y ^j, , Magnitude, From the figure For ΔOBN, we have, AN, B, BN, sin θ=, B, cos θ=, , =>, , AN =B cos θ, , =>, , BN =B sin θ, , From the diagram cos θ=, , OB 2=ON 2+ BN 2, , Ax, A, , ,, , sin θ=, , Ay, A, , --------> x component of A, --------> y component of A, , A x =A cosθ, A y = A sinθ, , where ‘A’ is the magnitude (length) of the, vector A and θ is the angle between A and the, x component of A . Also we will get, A= √ A 2x + A 2y, , This is law of cosines, tan θ=, , Direction, If R makes an angle α with A , then in, ΔOBN,, , Ay, Ax, , ,, , θ=tan, , −1, , Ay, Ax, , Thus the vector A is resolved into two, perpendicular components Ax and Ay along x, axis and y axis respectively., Problem1: Resolve the given force vector, along x and y direction and write the vector in, analytical form, , Do Example 4.3 NCERT, Analytical representation of vectors, (Resolution of vectors), In 3D a vector can be represented as, , Fy, , F=36N, , =300, Fx, , ⃗, A= A x ^i + A y ^j+ A z k^, , Soln ) Fx= F cosθ, =36 cos30 = 18√3, Fy= F sinθ, = 36 sin30 = 18, So the vector can be analytically represent as, F = 18√3 i + 18 j, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 19, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 22 :

4.3 VECTOR ADDITION – ANALYTICAL, METHOD, Let ⃗, A= A X ^i + A y ^j+ A z k^ and, , The position vector of r2 = x2 i +y2 j, Then the displacement vector , ∆r = r2 - r1, , = (x2 – x1) i + ( y2 –y1) j, , ⃗, B =B X ^i+ B y ^j+B z k^, R= ⃗, A+⃗, B =>, Then ⃗, , => ∆r = ∆x i + ∆ y j, 4.4 MOTION IN A PLANE, , ⃗, R=( A x + B x ) ^i +( A y + B y ) ^j+( A z +B z ) k^, , POSITION VECTOR, It is a vector which, denotes the position of, a particle at any instant, of time with respect to, some reference point., The position vector of, r is given by ⃗r =x ^i+ y ^j+ z k^, problem2:, Determine the, position, vectors for the, following, particles which, are located at, points P, Q, R,, S., Soln) rp= 3 i, rQ= 5 i + 4 j, rR= -2 i, rS= 3 i - 6 j, , VECTOR, Position vector ( r ), , EXPRESSION, r= x i + y j, , Displacement vector (dr) dr = dx i + dy j, Velocity vector (v), v=, , dr, dt, , Acceleration vector, dv, dt, , a=, , DISPLACEMENT VECTOR, , dr d, = ( x i+ y j), dt dt, dx dy, i+, j, =, dt dt, v = v x i+v y j, dv, dt, d, ( v i+ v y j), =, dt x, a= a x i+a y j, , a=, , 4.5 KINEMATIC EQUATIONS FOR, UNIFORM ACCELERATION FOR, MOTION IN A PLANE, Along x direction, V x =ux +a x t, , .....................(1), , 1, 2, S x =x=u x t+ ax t ..................(2), 2, , The position vector of r1 = x1 i +y1 j, , V 2x =u2x +2 a x S x ...................(3), , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 20, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 23 :

Along y direction, , V x =ucos θ+0 x t, , 1, 2, S y = y =u y t+ a y t, 2, 2, y, , 2, y, , V =u + 2a y S y, , ..............(9), , V x =u cosθ, , ..................(4), , V y =u y + a y t, , Similarly V y =u y + a y t, V y =u sin θ−g t ............(10), , ................(5), ..................(6), , 4.6 PROJECTILE MOTION, When an object is thrown in the air with, some initial velocity (NOT just upwards), and, then allowed to move under the action of, gravity alone, the object is known as a, projectile., The path followed by the particle is called its, trajectory ., Motion of a projectile is an example for motion, in a plane with constant acceleration ., Fig. shows Motion of an object projected with, velocity u at angle θ ., , NOTE:, 1) x-component of velocity remains constant, throughout the motion , only the y- component, of velocity changes, 2) At maximum height vy =0, 3) The velocity at any instant is given by the, relation V = √V 2x +V 2y, 4) At maximum height V=vx=ucosθ since, vy=0 at maximum height, 4.6.1 Equation of path of a projectile, From (8) x=u x t=ucosθ t, x, .............(11), u cos θ, 1, 2, y=u y t + a y t, 2, , =>, , t=, , From (5), , For projectile u y =u sinθ and a=−g, Therefore, , 1 2, y=usin θ t− g t ..............(12), 2, , Substitute (11) in (12), =>, After the object has been projected, the, acceleration acting on it is acceleration due to, gravity alone , which is directed vertically, downward., Ie, a x =0 , a y =−g ..............(7), The components of initial velocity are, u x =u cosθ, u y =u sinθ ...........(8), , usinθ x, g x2, −, ucos θ 2cos 2 θ, , y=tanθ x−, , g, x2, 2, 2 cos θ, , This is of the form y = a x + b x 2 , in which a, and b are constants. This is the equation of a, parabola, i.e. the path of the projectile is a, parabola., 4.6.2 Time of maximum height (tm ), We know V y =u sin θ−g t, (From eqn 10), At maximum height V y =0, Therefore ,, (10) => 0=u sinθ−g t m, , The components of velocity at any time t can be, obtained using Eq (1) , (4) , (7) and (8), ie,, , =>, , y=, , V x =ux +a x t, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 21, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 24 :

=>, , g t m =u sinθ, , =>, , t m=, , ie, Rmax=, , u sinθ, g, , ................(13), , Do Example 4.7 ,4.8 NCERT, 4.7 UNIFORM CIRCULAR MOTION, When an object follows a circular path at a, constant speed, the motion of the object is, called uniform circular motion., , 4.6.3 Time of flight (TF ), Th e total time taken by the projectile, from the point of projection till it hits the, horizontal plane is called time of flight., TF = 2 tm, T F=, , 2 usinθ, g, , u2, g, , 4.7.1 Some basic terms, 1. Angular displacement (θ), The angle swept over by the radius vector in a, given interval of time is called angular, displacement (θ)., , ..............(14), , 4.6.3 Maximum height of a projectile (hm), The maximum vertical distance travelled, by the projectile during its journey is called, maximum height., We know V 2y =u 2y + 2a y S y, ( From (6)), When the projectile is at maximum height, , ,, , S y =hm, , V y =0, , Therefore the above equation becomes, , =>, =>, , 0=(usinθ )2−2 g h m, , Unit : radian, , 2 g h m=u2 sin2 θ, , 2) Angular velocity (ω), Angular velocity is the rate of change of, angular displacement. It is a vector quantity., , 2, , hm =, , 2, , u sin θ, 2g, , ................(15), , Angular velocity , ω =, , =>, , =>, , 4) Frequency (f), Number of revolutions per second, , 2 usinθ, g, 2, u 2sin θ cos θ, R=, g, , R=(u cosθ), , R=, , dθ, dt, , 3) Time period (T), Time taken for one complete revolution, , 4.6.4 Horizontal range of a projectile (R), It is the horizontal distance travelled by a, projectile during its time of flight., R=V x X T F, Therefore, =>, , Dimension :No dimension, , 1, T, , f=, , Also ω=, , dθ, 2π, =, dt, T, , Relation between linear velocity and angular, velocity, , u2, sin 2 θ, g, , Velocity=, , NOTE : Horizontal range is maximum when, 2θ=90o . ie, θ=45o for a particular 'u', , ie,, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 22, , @, , ds, =, dt, , d, dθ, =, (r θ) =r, dt, dt, v =r ω, , SOHSS AREEKODE, , rω

Page 25 :

Angular acceleration (α), It is the rate of change of angular velocity, , α=, , dω, d v, 1 dv, =, =, ( ) =, dt, dt r, r dt, , ie,, , 2, Fc= m v = m ω2 r, , ie,, , r, , The centripetal force is always towards the, centre of the circle., 4.8 RELATIVE VELOCITY, , a, r, , a=r α, , Do Problem 4.8 NCERT, Add.Problem 1, A stone of mass 2 kg tied to the end of a, string 80 cm long is whirled in a horizontal, circle with a constant speed . If the stone makes, 14 revolutions in 25 seconds., (a) What is the angular velocity of the sone, (b) Centripetal acceleration, (c) Centripetal force, [Ans a) 3.52 rad/ s b) 9.9 m/s2 c) 19.8 N ], Add.Prob 2, Calculate the angular velocity of, (a) Second hand, (b) Minute hand and, (c) Hour hand of a clock, , 4.7.2 centripetal acceleration, Consider a particle executing uniform, circular motion with speed 'v' around a circle of, radius 'r'., Let the directions of position and velocity, vectors shift through the same angle θ in a, small interval of time ' Δt ' as shown in Figure., For uniform circular motion ,, , r = |r⃗1| = |r⃗2|, , and, , v= |v⃗1| = |v⃗2|, , Previous Questions, 1a) Find whether the given vectors 2 i +3 j + 4, k and 4 i + 6 j+ 8 k are parallel or not., b) What are orthogonal unit vectors?, , The magnitudes of the displacement Δr and, of Δv satisfy the following relation., Δv, v, , Δr, r, , | |=| |, =>, , Δv, , 2a) Obtain expression for Time of flight, for a projectile motion., b) What is the angle of projection for, maximum horizontal range?, c) The ceiling of a long hall is 25m, high. What is the maximum horizontal, distance that the ball thrown with a speed, of 40 m/s can go without hitting the ceiling, of the hall?, , = θ, , = v Δr, , r, 2, Δv, v Δr, a =, =, = v, Δt, r Δt, r, 2, v, a =, ie,, r, v =r ω, Also, ω2 r 2, a =, Therefore,, = ω2 r, r, , 3 . A stone is thrown upward from a moving, train., a) Name the path followed by the stone., b) ) A man throws a stone up into air at an, angle ' θ ' with the horizontal. Draw the, path of the projectile and mark directions, of velocity and acceleration at the highest, position, , 4.7.3 Centripetal force (Fc), The centripetal force is given by, F c=ma =, , mv 2, = m ω2 r, r, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 23, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 26 :

equal to three scalar equations., , CHAPTER FIVE, LAWS OF MOTION, 5.1 INTRODUCTION, Is an external force required to keep a, body in uniform motion?, Aristotle’s fallacy :An external force is required, to keep a body in motion., Galileo arrived at a new insight on motion, from his inclined plane experiments which, corrected Aristotle's idea., Inertia: Inertia is the inability of an object to, change its velocity by itself. This includes changes, to the object's speed, or direction of motion., , 5.2 NEWTON'S LAWS OF MOTION, 5.2.1 Newton’s First Law ( Law of inertia), Every body continues to be in the state of rest, or in the state of uniform motion (constant, velocity) unless there is external force acting, on it., , Problem : example 5.1 NCERT, Momentum (p) :Momentum of a body is the, product of its mass m and velocity, v, P=mv, 5.2.2 Newton’s second Law, The force acting on an object is equal to, the rate of change of its momentum, ═>, , Unit of Force ═> newton, Thus One Newton is defined as the force which, acts on 1 kg of mass to give an acceleration, 1 ms−2 in the direction of the force., NOTE, Newton’s laws are vector laws. The equation, F= ma is a vector equation and essentially it is, , By comparing both sides, the three scalar, equations are, Fx= max . The acceleration along the x direction, depends only on the component of force acting, along the x-direction. And, Fy= may .Th e acceleration along the y, direction depends only on the component, of force acting along the y-direction., , FZ= maZ, From the above equations, we can infer that the, force acting along y direction cannot alter the, acceleration along x direction. In the same way,, F z cannot affect a y and a x ., Problem : example 5.2 NCERT, 5.2.3 Newton’s third Law, Newton’s third law states that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction., Action and reaction pair of forces do not act on, the same body but on two different bodies. So, they don't cancel each other. Any one of the, forces can be called as an action force and, the other the reaction force. These actionreaction forces are not cause and effect forces., 5.3 IMPULSIVE FORCE, The force which acts for a very short, interval of time is called impulsive force., Eg: - (i) The force on a ball when hit with a bat., (ii) Force exerted on a bullet when fired from a, gun., 5.4 IMPULSE (I), Impulse of a force is the product of the, force and the time for which the force acts on, the body. Impulse is a measure of the total, effect of force., i.e, Impulse, I = force x time = Change in, momentum, i.e, I = F dt = dp where dt is the time for which, the force F acts., Problem : example 5.4 NCERT, Problem:, Show that Impulse= Change in momentum, using Newton's second law., Soln) According to second law, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 24, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 27 :

NOTE, The graphical representation of constant, force impulse and variable force impulse ( Area, under the graph give impulse), Soln) (a) (i)Downward gravitational force along, negative y direction (mg) ii) Tension (T) along, the two strings, (b) since the boy is in, equilibrium (rest),, 2T cosθ = mg, Problem:An object of mass 10 kg moving with, a speed of 15 m s −1 hits the wall and comes to, rest within a) 0.03 second, b) 10 second ., Calculate the impulse and average force acting, on the object in both the cases., [ Ans : a) Impulse= -150 N s Fav=-5000 N, b) Impulse= -150 N s Fav=-15 N ], 5.5 EQUILIBRIUM OF FORCES, , when the net external force on the, particle is zero , then the body is in equilibrium., ie, Even under action of forces the object will, be at rest . If the lines of forces are acting at a, common point , then the collection of forces is, said to be concurrent forces ( Fig Below), Prob: A baby is playing in a swing which is, hanging with the help of two identical chains is, at rest.(a) Identify the forces acting on the, baby. (b)find out the tension acting on the, chain, , => T= mg/ 2cosθ, NOTE, When θ = 0 °, the strings are, vertical and the tension on each string is, T = mg/2, 5.6 CONSERVATION OF MOMENTUM, If there are no external forces acting on, the system, then the total linear momentum of, the system ( p tot ) is always a constant vector., In other words, the total linear momentum of, the system is conserved in time. Here the word, ‘conserve’ means that p 1 and p 2 can vary, in, such a way that p 1 +p 2 is a constant vector., When two particles interact with each other,, they exert equal and opposite forces on each, other., Let F 21 → Force acting on 2 by 1, F 12 →Force acting on 1 by 2, Then by Newton's third law, ⃗, F21=−⃗, F 12 ......................(1), In terms of momentum of particles, the, force on each particle (Newton’s second law), can be written as, ⃗, F12=, , (1)=>, =>, =>, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 25, , @, , d⃗, P1, dt, , and, , ⃗, F21=, , d⃗, P2, ..............(2), dt, , d⃗, P1 −d ⃗, P2, =, dt, dt, d⃗, P1 d ⃗, P2, +, =0, dt, dt, d ⃗ ⃗, ( P + P )=0, dt 1 2, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 28 :

ie,, p 1 + p2 = constant vector, Example 1 : Recoil of gun., , (always)., , System = Gun and bullet, M – mass of Gun, m – mass of bullet, U – inial velocity of gun, u– inial velocity of, bullet, Let momentum of the gun before, firing = p1=MU=0, momentum of the bullet before, firing = p2=mu=0, Total momentum of the system before, firing =p1 + p2 = 0, After firing bullet moves with a velocity, v, forward. According to the law of conservation, of linear momentum, total linear momentum, has to be zero after the firing also., Ie,, p1I + p2I = 0, => p1! + mv =0, => p1I = -mv, is the recoil momentum, , => MV= -mv, => V= -mv/M, , is the recoil velocity., The - ve sign shows that the gun is recoiling., Example 2 : Rocket Propulsion, In case of rocket, a fuel burnt in the, combustion chamber produces hot gas, which is, allowed to escape through a nozzle at the back, of the rocket. This produces a backward, momentum on the gas and the rocket acquires, an equal forward momentum. Thus the rocket, moves forward, Problem : A shell of mass 0.020 kg is fired by, a gun of mass 100 kg. If the muzzle speed of, the shell is 80 m/s, what is the recoil speed of, the gun?, , 1) Static friction, 2) Kinetic friction., 5.7.1 Static friction (fs), Static friction is the force which opposes, the initiation of motion of an object on the, surface., If some external force F is applied on an, object parallel to the surface on which the, object is at rest, the surface exerts exactly an, equal and opposite force on the object to resist, its motion and tries to keep the object at rest ., But if the external force is increased, after a, particular limit, the surface cannot provide, sufficient opposing frictional force to balance, the external force on the object, then the object, starts to slide. The maximum value of frictional, force before the body just slides over the, surface of another body is called limiting, friction or maximum static friction (fsmax)., Experimentally, it is found that the, magnitude of the maximum static friction, fsmax α Normal force, N, OR, where µs- coefficient of static friction, NOTE: Law of static friction, The static friction does not depend upon the, area of contact. And, 5.7.2 Kinetic Friction, When an object slides, the surface exerts, a frictional force called kinetic friction fk (also, called sliding friction or dynamic friction)., Experimentally it is found that, NOTE: Since μk< μs , starting of a motion is, more difficult than maintaining it., , [Ans = 0.016 m/s], 5.7 FRICTION, Frictional force is the force which, always opposes the relative motion between an, object and the surface where it is placed., Frictional force always acts on the object, parallel to the surface on which the object is, placed. There are two kinds of friction namely, , When, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 26, , @, , relative, , motion, , has, , SOHSS AREEKODE, , begun,, , the

Page 29 :

acceleration of the body according to the, second law is ( F – fk )/m. For a body moving, with constant velocity, F = fk .If the applied, force on the body is removed, its acceleration is, – fk /m and it eventually comes to a stop., 5.7.3 Angle of Friction OR Angle of repose, Consider an inclined plane on which an object, is placed, as, shown in, Figure, Let the angle, which this, plane makes, with the, horizontal be θ. For small angles of θ , the, object may not slide down. As θ is increased,, for a particular value of θ , the object begins to, slide down. This value is called angle of repose, or angle of friction., Expression, From the above Fig. Since the body is in, equilibrium, ...............(1), ..............(2), ..................... (3), Equating the right hand side of equations, (2) and (3), we get, ie,, 5.7.4 Rolling Friction, In rolling motion when a wheel moves, on a surface, the point of contact with surface is, always at rest. Since, the point of contact is, at rest, there is no, relative, motion, between the wheel, and surface. Hence, the frictional force is, very less., However , Due to the elastic nature of, the surface at the point of contact there will be, some deformation on the object at the point on, , the wheel or surface. Due to this deformation,, there will be minimal friction between wheel, and surface. It is called ‘rolling friction’. In, fact, ‘rolling friction’ is much smaller than, kinetic friction., Do Examples 5.7,5.8,5.9 NCERT, 5.8 APPARENT WEIGHT (Motion of a body, in a lift), , Case (i) : When the lift is stationary or moving, up or down with a uniform velocity (a=0), Then Force, R - mg = 0, => R = mg (real weight), Case (ii) : When the lift moves up with an, acceleration, a, R - mg = ma =>R = mg +ma, => R = m(g +a), Case (iii) When the lift moves down with an, acceleration , a, R - mg = - ma =>R = mg - ma, => R = m(g – a), Case (iv) When the lift falls down freely., R=m (g-g)=0, 5.9 DYNAMICS OF CIRCULAR MOTION, 5.9.1 Centripetal Force, The centripetal acceleration of a particle, in the circular motion is given by ,, From Newton's second law the, centripetal force is given by, Note that , to execute, circular motion centripetal force is essential., The origin of the centripetal force can be, gravitational force, tension in the string,, frictional force, Coulomb force etc. Any of, these forces can act as a centripetal force., 1)In the case of whirling motion of a stone tied, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 27, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 30 :

to a string, the centripetal force on the particle, is provided by the tensional force on the string., 2) In motion of satellites around the Earth,the, centripetal force is given by Earth’s, gravitational force on the satellites., 3)When a car is moving on a circular track the, centripetal force is given by the frictional force, between the road and the tyres., 5.9.2 Motion of a car on a level road, , Fig. Forces acting on the vehicle on a leveled, circular road, Th ere are three forces acting on the vehicle, when it moves as shown in the Figure, 1.Gravitational force (mg) acting downwards, 2.Normal force (mg) acting upwards, 3. Frictional force (fs ) acting horizontally, inwards along the road, As there is no acceleration in the vertical, direction, N = mg ..............(1), , Consider a vehicle of mass m moving on, a banked curve. Then various forces acting on, the car are, 1) The gravitational force (weight) mg, downward, 2) Normal force N normal to the road, 3) Frictional force f s , acting parallel to the, road., Since there is no acceleration along the vertical, direction, the net force along this direction must, be zero. Hence,, N cos θ = mg + f sin θ ..........(1), The centripetal force is provided by the, horizontal components of N and f., ..............(2), , Then Eqn (1) and (2) become, , The centripetal force is provided by the, force of static friction fs between the tyre and, surface of the road. ie, Static friction opposes, the impending motion of the car moving away, from the circle., Ie,, , ................(3), , ..............(4), From (3), ..................., , (5), , Substituting value of N in Eq. (4), we get, This shows that for a given value of μ s and R,, there is a maximum speed of circular motion of, the car possible, namely, ..................(6), maximum possible speed of a car on a banked, road is greater than that on a flat road., , Note: vmax is independent of mass of the car., 5.9.3Motion of a car on a banked road, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 28, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 31 :

For μs = 0 , v0= (R g tanθ )1/2, At this speed, frictional force is not needed at, all to provide the necessary centripetal force., Driving at this speed on a banked road will, cause little wear and tear of the tyres., Do Example 5.10 NCERT, Problem 1 : Consider a circular levelled road of, radius 10 m having coefficient of static friction, 0.81. Three cars (A, B and C) are travelling with, speed 7 m/s , 8 m/s and 10 m/s respectively., Which car will skid when it moves in the, circular level road?(g =10 m/s2), Ans : car C, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 29, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 32 :

CHAPTER SIX, , soln), , WORK, ENERGY AND POWER, 6.1 INTRODUCTION, In physics work means mechanical work., Work is said to be done by a force, when the, force applied on a body displaces it., work is also defined as ‘the product of, displacement and the component of force in the, direction of displacement., Energy is the capacity to do work. So it, has the same unit and dimension of work., Power is the rate of change of work done., 6.2 SCALAR PRODUCT ( DOT PRODUCT), If there are two vectors A and B having, an angle θ between them, then their scalar, product is defined as A ⋅ B = AB cosθ . Here, A, and B are magnitudes of A and B ., Properties, 1.The product quantity A ⋅ B is always a scalar., 2.The scalar product is commutative,, ie, A ⋅ B= B . A, 3.The vectors obey distributive law . ie,, A . (B + C) = (A . B ) + (A . C), 3.The angle between the vectors, , NOTE: Geometrical interpretation of dot product, , (a) The scalar product of two vectors A and B is a, scalar : A. B = A B cos θ (b) B cos θ is the, projection of B onto A (c) A cos θ is the projection, of A onto B., ie. A.B= AB cos θ => magnitude of A x projection, of B onto A, B.A = BA cosθ => magnitude of B x projection of, A onto B, , 4. A . B= AB , if θ= 0o, A . B= 0 , if θ= 90o, A . B= -AB , if θ= 180o, 5. For unit vectors, , 6. In terms of components the scalar product of, A and B can be written as, , 7. The magnitude of vector A is given by, , A . A = Ax Ax + Ay Ay + Az Az = AA=A2, ie ,, problem1, , 6.2 WORK, The work done by the force is defined to, be the product of component of the force in the, direction of the displacement and the magnitude, of this displacement., ie, W= Fcosθ x d, NOTE, Work done is zero in the following cases., 1) When the force is zero (F = 0)., 2) When the displacement is zero (d = 0)., Eg : when force is applied on a rigid wall it, does not produce any displacement., 3)When the force and displacement are, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 30, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 33 :

perpendicular (θ = 90 o ) to each other., Eg:when a body moves on a, horizontal direction, the, gravitational force (mg) does no, work on the body, since it acts at, right angles to the displacement ., In circular motion the centripetal, force does not do work on the, object moving on a circle as it is, always perpendicular to the, displacement., Problem 2:A box is pulled with a force of, 25 N to produce a displacement of 15 m. If the, angle between the force and displacement, is 30 o , find the work done by the force., [Ans : 324.76 J], , NOTE : The work-kinetic energy theorem, implies the following., 1) If the work done by the force on the body is, positive then its kinetic energy increases., 2) If the work done by the force on the body is, negative then its kinetic energy decreases., 3) If there is no work done by the force on the, body then there is no change in its kinetic, energy, which means that the body has moved, at constant speed provided its mass remains, constant., Relation between Momentum and Kinetic, Energy, OR, Do Example 6.2 , 6.3 NCERT, , HW 6.4, , 6.5WORK DONE BY A VARIABLE FORCE, Problem 3 : Find the angle between force, F=( 3i+4j-5k ) unit and displacement d=, ( 5i+4j+3k ) unit, [ Ans : cos-10.32], , A plot of varying force, in one dimension shown, in figure., , 6.3 KINETIC ENERGY, Kinetic energy is the energy possessed, by a body by virtue of its motion. All moving, objects have kinetic energy., , If the displacement Δx is small , we can take, F(x) is approximately constant and work done, is then, , 6.4 WORK–KINETIC ENERGY, THEOREM (For Constant Force), For constant acceleration ( constant force) , we, know, .............. (1), , This is, illustrated in this, Fig ., , where u and v are the initial and final speeds, and s the distance traversed. Multiplying both, sides by m/2, we have, , Adding successive rectangular areas in Fig. we, get the total work done as, , .............(2), ie, Final Kinetic Energy- Initial Kinetic, Energy= Work done, , where the summation is from the initial position, x i to the final position x f ., , Kf – Ki =ΔK =W, ie, The change in kinetic energy of a particle is, equal to the work done on it by the force. This, is called work-kinetic energy theorem., , If the displacements are allowed to approach, zero, then the number of terms in the sum, increases without limit, but the sum approaches, a definite value equal to the area under the, , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 31, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 34 :

curve., Then the work done is, , The gravitational potential energy (U) at some, height h is equal to the amount of work required, to take the object from ground to that height h, with constant velocity., The gravitational potential energy, (U) at some height h is equal to the, amount of work required to take the, object from the ground to that height, h at constant velocity., Fg = -mg j (downward), Fa = mg j ( upward), d= h j (upward ), , = Area under the curve, Do example 6.5 NCERT, Problem4:A variable force F = k x 2 acts on a, particle which is initially at rest. Calculate the, work done by the force during the, displacement of the particle from x= 0 m to x, =4 m. (Assume the constant k= 1 N m -2, , 6.5.1 Work Energy theorem for variable, force( see last page) *, 6.6 POTENTIAL ENERGY, The energy possessed by a body by, virtue of its position( in a field ) or, configuration ( in a state of strain) is called, potential energy., Potential energy of an object at a point P, is defined as the amount of work done by an, external force in moving the object at constant, velocity from the point O (initial location) to, the point P (final location). At initial point O, potential energy can be taken as zero., We have various types of potential energies., 1. Gravitational potential energy: The energy, possessed by the body due to gravitational force, gives rise to gravitational potential energy., 2. Elastic potential energy :The energy due to, spring force and other similar forces give rise to, elastic potential energy., 3. Electrostatic potential energy: The energy, due to electrostatic force on charges gives rise, to electrostatic potential energy.( Next year), 1.Gravitational Potential energy near the, surface of the Earth, , U= Fa .d, = mg j. h j = mgh cos0 = mgh, ie, U = mgh, 2. ELASTIC POTENTIAL ENERGY, ( POTENTIAL ENERGY OF A SPRING), When a spring is elongated, it develops a, restoring force. The potential energy possessed, by a spring due to a deforming force which, stretches or compresses the spring is termed as, elastic potential energy. The work done by the, applied force against the restoring force of the, spring is stored as the elastic potential energy in, the spring., , Fs =- Kx, Fa = Kx, , Force-displacement graph for a spring, The elastic potential, energy can be easily, calculated by drawing a, F - x graph. The shaded, area (triangle) is the work, done by the spring, force., , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 32, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 35 :

6.7 CONSERVATIVE FORCE, A force is said to be a conservative force, if the work done by the force in moving the, body depends only on the initial and final, positions of the body and not on the nature of, the path followed between the initial and final, positions., There will be a potential energy, associate with a conservative force., Total mechanical energy remains, constant in a conservative force field., Eg :Elastic spring force, Electrostatic, force, Magnetic force, Gravitational force, etc., 6.8 NON CONSERVATIVE FORCE, A force is said to be non-conservative if, the work done by or against the force in moving, a body depends upon the path between the, initial and final positions., Eg: Frictional forces, The force due to, air resistance, viscous force , etc., 6.9 THE CONSERVATION OF, MECHANICAL ENERGY (IN CASE OF A, FREELY FALLING BODY), U=mgh, K=0,, E=U+K=mgh, , reaction, heat is released and the reaction is said to, be an exothermic reaction. If the reverse is happens,, heat is absorbed and the reaction is endothermic., 3.Electrical Energy: Energy is associated with an, electric current, 4.The Equivalence of Mass and Energy (Nuclear, energy):, Albert Einstein, E=mc2, The energy released from the nuclear reactions,, either fission or fusion, is called as nuclear energy., Nuclear fusion and fission are manifestations of the, equivalence of mass and energy., , 6.11 POWER, Power is a measure of how fast or slow a, work is done. Power is defined as the rate of, work done or energy delivered., , Unit: watt, 1 W = 1 J /s, 1 hp = 746 w, 1 kW = 1000 W, Note: kWh is the unit of energy not of power, 1 kWh= 3.6×10 6 J, Average power, Instantaneous power, , U=mg(h-y) ,, =1/2 m(2gy)= mgy, E=U+K= mgh, , 6.11.1 Relation between Power and velocity, , The work dW done by a force F for a, displacement dr is dW = F.dr, , U=0, K= 1/2 mv2, =1/2 m(2gh)=mgh, E= U+K = mgh, , Therefore, , [NOTE : In case of spring , the conservation of, mechanical energy will be discussed in the, chapter 14 , oscillations], 6.10 VARIOUS FORMS OF ENERGY, 1. Heat: The work done by friction is not ‘lost’,, but is transferred as heat energy., 2.Chemical Energy: Chemical energy arises from, the molecules participating in the chemical reaction, have different binding energies. If the total energy, of the reactants is more than the products of the, , Do Example 6.11 NCERT, 6.12 COLLISIONS, A collision is said to have taken place if two, moving objects strike each other or come close, to each other such that the motion of one of, them or both of them changes suddenly. Total, momentum will be conserved in all types of, collision., , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 33, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 36 :

Types of collisions, (1) Elastic collision, (2) Inelastic collision, (1) Elastic collision, Elastic collision is one in which both, momentum and kinetic energy is conserved., Total kinetic energy before collision = Total, kinetic energy after collision, (2) Inelastic collision, A collision in which total kinetic energy is not, conserved. ( Note:Total energy is conserved in, all types of collision), Total kinetic energy before collision ≠, Total kinetic energy after collision, completely inelastic collision., A collision in which the two particles move, together after the collision is called a, completely inelastic collision., 6.12.1 Elastic collisions in one dimension, Two elastic bodies of masses m1 and m2, moving in a straight line (along positive x, direction) on a frictionless horizontal surface as, shown in Figure., , ie,, , KE i = KE f, , =>, , └ ---------(4), (4)/(3)=>, , =>, =>, This means that for any elastic head on, collision, the relative speed of the two bodies, after the collision has the same magnitude as, before collision but in opposite direction., To find the final velocities v1 and v2, From the above equation, .................... (5), , In order to have collision, u1 >, , u2, , For elastic collision, the total linear momentum, and kinetic energies of the two bodies before, and after collision must remain the same., , ..................... (6), Substitute (6) in (3) =>, , Total linear momentum before collision,, .................(1), Total linear momentum after collision,, ..................(2), From the law of conservation of linear, momentum, pi = pf, , .............(3), , └---------> (7), Substitute (7) in (6) =>, , since the collision is elastic,Total kinetic energy, also will be conserved, , ..............(8), , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, 34, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 38 :

CHAPTER SEVEN, , SYSTEM OF PARTICLES AND, ROTATIONAL MOTION, Rigid Body, A rigid body is a body with a perfectly, definite and unchanging shape. The distance, between any two points in the body always, remains same even under the action of, external forces., What kind of motion can a rigid body, have?, Pure translation: In pure translational motion, at any instant of time every particle of the, body has the same velocity. ( Fig (a),(b)), , Fig(a):Translational (sliding) motion of a block down, an inclined plane. (Any point like P 1 or P 2 of the, block moves with the same velocity at any instant of, time.), , Fig(d): Motion of a rigid body which is a combination, of translation and rotation., , Rotation about a fixed axis, In rotation of a rigid body about a fixed, axis,every particle of the body moves in a, circle, which lies in a plane perpendicular to, the axis and has its centre on the axis., , Fig : Rotation about a fixed axis : A ceiling fan and, a potter’s wheel ., , Rotation(Axis is not fixed,but a point on, the axis is fixed), , Fig(b): Motion of a rigid body which is pure, translation., , Translation plus Rotation, A system is said to be in rotational plus, translational motion, when the particle is, rotating with some angular velocity about a, movable axis. (Fig c ,d), Fig(c): Rolling, motion of a, cylinder. It is not, pure translational, motion. Points P 1 ,, P 2 , P 3 and P 4 have, different velocities, (shown by arrows), at any instant of time.In fact, the velocity of the point, of contact P 3 is zero at any instant, if the cylinder, rolls without slipping., , Fig:A spinning top (The point of contact of the top, with the ground, its tip O, is fixed.) and An oscillating, table fan with rotating blades. The pivot of the fan,, point O, is fixed. The blades of the fan are under, rotational motion, whereas, the axis of rotation of the, fan blades is oscillating., , Note, The motion of a rigid body which is not, pivoted or fixed in some way is either a pure, translation or a combination of translation and, rotation. The motion of a rigid body which is, pivoted or fixed in some way is rotation., , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , 36, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 39 :

Centre Of Mass, The centre of mass of a system is the point, where all the mass of the system may be, assumed to be concentrated and where the, resultant of all the external forces acts., Centre of mass of a two particle system, Consider a system of two particles with, masses m1 and m2 and their position vectors, be r1 and r2 respectively from some arbitrary, origin O., , Z=, , m 1 z 1 +m2 z 2 +m3 z3 +........, m 1+ m2 +m3 +........, , (* Do Example 7.1 ,7.2,7.3 NCERT), Motion of centre of Mass, From (1) ,, =>, , m1 r 1+m2 r 2 +m3 r 3 +........, m1 +m2 +m3 +........, MR=m1 r 1 +m2 r 2+m3 r 3 +........, R=, , Differentiating wrto time ,, =>, , dr, dr, dr, dR, =m1 1 + m 2 2 +............. mn n, dt, dt, dt, dt, MV =m1 v 1 +m2 v 2+ ...........mn v n, , M, , =>, , Again differentiating wrto time,, =>, , dv, dv, dv, dV, =m1 1 +m2 2 +............. mn n, dt, dt, dt, dt, MA=m1 a1 +m2 a 2+........... m n an, , =>, , MA=F 1+ F 2 +........... F n, , =>, The centre of mass will be at a point C whose, position vector is given by, R=, , m 1 r 1 +m 2 r 2, m1 +m 2, , If the particles have the same mass, m1 = m2 =, m , then,, R=, , m r 1+ mr 2, m+ m, , =>, , R=, , r 1 +r 2, 2, , Thus, , if the particles are having same mass, the, centre of mass lies exactly midway between, them., Centre of mass of an N particle system, Consider a system of N particles of masses, m 1 , m 2 , m 3 ........ having position vectors, r 1 , r 2 , r 3 ,.........., The total mass of the system, M = m 1 + m 2 +, m 3 +........., m1 r 1+ m2 r 2 +m3 r 3 +........, ...........(1), m1 +m2 +m3 +........, mr, ∑ mi ri, =>, R=, R=∑ i i, mi, M, , Then R=, or, , In terms of co ordinates (the co ordinates of, the centre of mass),, X=, , m1 x 1 +m2 x 2 +m3 x 3 +........, m1 +m2+m3 +........, , Y=, , m1 y 1 +m2 y 2+ m3 y 3 +........, m 1+m2 +m3 +........, , M, , NOTE: The force F1 on the first particle is not, a single force,but the vector sum of all the, forces on the first particle ; likewise for the, second particle etc. Among these forces on, each particle there will be external forces, exerted by bodies outside the system and also, internal forces exerted by the particles on one, another. We know from Newton’s third law, that these internal forces occur in equal and, opposite pairs and in the sum of forces in the, above equation, their contribution is zero., Only the external forces contribute to the, equation. We can then rewrite the above, equation as, MA=F ext ................(2), where A is the acceleration of the centre of, mass and Fext represents the sum of all, external forces acting on the particles of the, system., Eqn (2) states that the centre of mass of, a system of particles moves as if all the mass, of the system is concentrated at the centre of, mass and all the external forces are applied, at that point., , KAMIL KATIL VEETIL, , 37, , @, , SOHSS AREEKODE

Page 40 :