Page 1 :

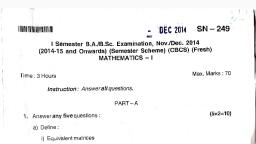

B. Sc. DEGREE PROGRAMME, (2020 Admission onwards), , COPLEMENTARY MATHEMATICS, SECOND SEMESTER, COPLEMENTARY : MTS2C02 -, , MATHEMATICS-2, 4 hours/week, 3 Credits, 75 Marks [Int:15+Ext:60]

Page 2 :

SECOND SEMESTER, MTS2 C02:MATHEMATICS-2, 4 hours/week, , 3 Credits, , 75 Marks [Int:15+Ext:60], , Syllabus, Text (1), , Calculus I (2/e) : Jerrold Marsden & Alan Weinstein Springer-Verlag New, York Inc(1985) ISBN 0-387-90974-5, , Text (2), , Calculus II (2/e) : Jerrold Marsden & Alan Weinstein Springer-Verlag New, York Inc(1985) ISBN 0-387-90975-3, , Text (3), , Advanced Engineering Mathematics(6/e) : Dennis G Zill Jones & Bartlett, Learning, LLC(2018)ISBN: 978-1-284-10590-2, , Module- I, , Text (1) & (2), , 14 hrs, , 5.1: Polar coordinates and Trigonometry – Cartesian and polar coordinates, (Only representation of points in polar coordinates, relationship between Cartesian and, polar coordinates, converting from one system to another and regions represented by, inequalities in polar system are required), 5.3 : Inverse functions-inverse function test, inverse function rule, 5.6: Graphing in polar coordinates- Checking symmetry of graphs given in polar equation,, drawings, tangents to graph in polar coordinates, 8.3: Hyperbolic functions- hyperbolic sine, cosine, tan etc., derivatives, anti differentiation, formulas, 8.4: Inverse hyperbolic functions- inverse hyperbolic functions (their derivatives and anti, derivatives), 10.3: Arc length and surface area- Length of curves, Area of surface of revolution about x, and y axes, , Module- II, , Text (2), , 17 hrs, , 11.3: Improper integrals- integrals over unbounded intervals, comparison test, integrals of, unbounded functions, 11.4: Limit of sequences and Newton’s method ε-N definition, limit of powers,, comparison test, Newton’s method, 11.5: Numerical Integration- Riemann Sum, Trapezoidal Rule, Simpson’s Rule, , 82, , Page 84 of 100

Page 3 :

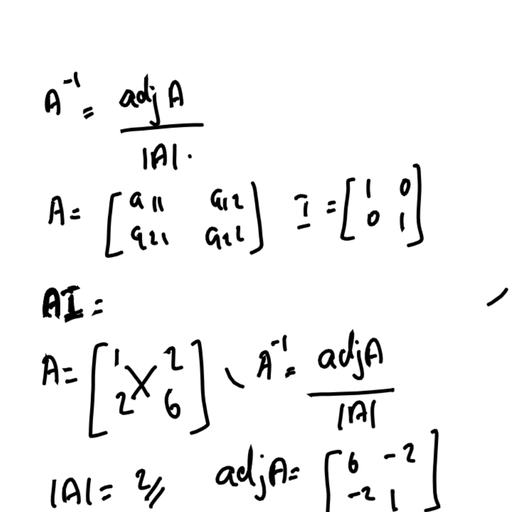

12.1: The sum of an infinite series- convergence of series, properties of limit of sequences, th, , (statements only), geometric series, algebraic rules for series, the i term test, 12.2: The comparison test and alternating series- comparison test, ratio comparison test,, alternating series, alternating series test, absolute and conditional convergence, , Text (3), , Module- III, , 19 hrs, , 7.6: Vector spaces – definition, examples , subspaces, basis, dimension, span, 7.7: Gram-Schmidt Orthogonalization Process- orthonormal bases for ℝ n, construction of, n, , orthonomal basis of ℝ, , 8.2: Systems of Linear Algebraic Equations- General form, solving systems, augmented, matrix, Elementary row operations, Elimination Methods- Gaussian elimination, Gauss–, Jordan elimination, row echelon form, reduced row echelon form, inconsistent system,, networks, homogeneous system, over and underdetermined system, 8.3: Rank of a Matrix- definition, row space, rank by row reduction, rank and linear system,, consistency of linear system, 8.4: Determinants- definition, cofactor (quick introduction), 8.5: Properties of determinant- properties, evaluation of determinant by row reducing to, triangular form, , Module- IV, , Text (3), , 14 hrs, , 8.6: Inverse of a Matrix – finding inverse, properties of inverse, adjoint method, row, operations method, using inverse to solve a linear system, 8.8: The eigenvalue problem- Definition, finding eigenvalues and eigenvectors, complex, eigenvalues, eigenvalues and singular matrices, eigenvalues of inverse, 8.9: Powers of Matrices- Cayley Hamilton theorem, finding the inverse, 8.10: Orthogonal Matrices- symmetric matrices and eigenvalues, inner product, criterion for, orthogonal matrix, construction of orthogonal matrix, 8.12:, Diagonalizationdiagonalizable, matrix-sufficient, diagonalizability of symmetric matrix, Quadratic Forms, , 83, , conditions,, , orthogonal, , Page 85 of 100

Page 4 :

References:, 1 Soo T Tan: Calculus Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning(2010 )ISBN 0-534-46579-X, 2 Gilbert Strang: Calculus Wellesley Cambridge Press(1991)ISBN:0-9614088-2-0, 3, , Ron Larson. Bruce Edwards: Calculus(11/e) Cengage Learning(2018) ISBN: 978-1-33727534-7, , 4, , Robert A Adams & Christopher Essex : Calculus Single Variable (8/e) Pearson Education, Canada (2013) ISBN: 0321877403, , 5, , Joel Hass, Christopher Heil & Maurice D. Weir : Thomas’ Calculus(14/e), Pearson (2018) ISBN 0134438981, , 6, , Advanced Engineering Mathematics(7/e) Peter V O’Neil: Cengage, Learning(2012)ISBN: 978-1-111-42741-2, , 7, , Erwin Kreyszig: Advanced Engineering Mathematics(10/e) John Wiley & Sons(2011), ISBN: 978-0-470-45836-5, , 8, , 1Glyn James: Advanced Modern Engineering Mathematics(4/e) Pearson Education, Limited(2011) ISBN: 978-0-273-71923-6, , 84, , Page 86 of 100

Page 5 :

MODULE 1, Text (1) Calculus I (2/e) : Jerrold Marsden & Alan, Weinstein Springer-Verlag New York Inc(1985) ISBN, 0387909745, Text (2) Calculus II (2/e) : Jerrold Marsden & Alan, Weinstein Springer-Verlag New York Inc(1985) ISBN, 0387909753, Sections 5.1, 5.3, 5.6 - Text (1), 8.3, 8.4, 10.3 - Text (2)

Page 74 :

MODULE 2, Text (2) Calculus II (2/e) : Jerrold Marsden & Alan, Weinstein Springer-Verlag New York Inc(1985) ISBN, 0387909753, Sections 11.3-11.5, 12.1-12.2

Page 129 :

MODULE 3, Text (3) Advanced Engineering Mathematics(6/e) :, Dennis G Zill Jones & Bartlett Learning,, LLC(2018)ISBN: 9781284105902, Sections 7.6-7.7, 8.2-8.5

Page 130 :

63. Determine which of the following planes are perpendicular, , 43. ( 12 , 34 , � 12 ); 6i � 8j � 4k, 44. (�1, 1, 0); �i � j � k, , In Problems 45–50, find, if possible, an equation of a plane that, contains the given points., 45., 46., 47., 48., 49., 50., , (3, 5, 2), (2, 3, 1), (�1, �1, 4), (0, 1, 0), (0, 1, 1), (1, 3, �1), (0, 0, 0), (1, 1, 1), (3, 2, �1), (0, 0, 3), (0, �1, 0), (0, 0, 6), (1, 2, �1), (4, 3, 1), (7, 4, 3), (2, 1, 2), (4, 1, 0), (5, 0, �5), , In Problems 65–68, find parametric equations for the line of, intersection of the given planes., , In Problems 51–60, find an equation of the plane that satisfies, the given conditions., 51., 52., 53., 54., 55., 56., 57., 58., 59., 60., 61., , 62., , to the line x � 4 � 6t, y � 1 � 9t, z � 2 � 3t., (a) 4x � y � 2z � 1, (b) 2x � 3y � z � 4, (c) 10x � 15y � 5z � 2 (d) �4x � 6y � 2z � 9, 64. Determine which of the following planes are parallel to the, line (1 � x)/2 � (y � 2)/4 � z � 5., (a) x � y � 3z � 1, (b) 6x � 3y � 1, (c) x � 2y � 5z � 0, (d) �2x � y � 2z � 7, , Contains (2, 3, �5) and is parallel to x � y � 4z � 1, Contains the origin and is parallel to 5x � y � z � 6, Contains (3, 6, 12) and is parallel to the xy-plane, Contains (�7, �5, 18) and is perpendicular to the y-axis, Contains the lines x � 1 � 3t, y � 1 � t, z � 2 � t;, x � 4 � 4s, y � 2s, z � 3 � s, y�1, z25, x21, �, �, ;, Contains the lines, 2, �1, 6, r � �1, �1, 5� � t �1, 1, �3�, Contains the parallel lines x � 1 � t, y � 1 � 2t, z � 3 � t;, x � 3 � s, y � 2s, z � �2 � s, Contains the point (4, 0, �6) and the line x � 3t, y � 2t,, z � �2t, Contains (2, 4, 8) and is perpendicular to the line x � 10 � 3t,, y � 5 � t, z � 6 � 12 t, Contains (1, 1, 1) and is perpendicular to the line through, (2, 6, �3) and (1, 0, �2), Let �1 and �2 be planes with normal vectors n1 and n2,, respectively. �1 and �2 are orthogonal if n 1 and n2 are, orthogonal and parallel if n1 and n2 are parallel. Determine, which of the following planes are orthogonal and which, are parallel., (a) 2x � y � 3z � 1, (b) x � 2y � 2z � 9, (d) �5x � 2y � 4z � 0, (c) x � y � 32 z � 2, (e) �8x � 8y � 12z � 1 (f ) �2x � y � 3z � 5, Find parametric equations for the line that contains (�4, 1, 7), and is perpendicular to the plane �7x � 2y � 3z � 1., , 7.6, , 65. 5x � 4y � 9z � 8, , x � 4y � 3z � 4, 67. 4x � 2y � z � 1, x � y � 2z � 1, , x � 2y � z � 2, 3x � y � 2z � 1, 68. 2x � 5y � z � 0, y, �0, 66., , In Problems 69–72, find the point of intersection of the given, plane and line., 69., 70., 71., 72., , 2x � 3y � 2z � �7; x � 1 � 2t, y � 2 � t, z � �3t, x � y � 4z � 12; x � 3 � 2t, y � 1 � 6t, z � 2 � 12 t, x � y � z � 8; x � 1, y � 2, z � 1 � t, x � 3y � 2z � 0; x � 4 � t, y � 2 � t, z � 1 � 5t, , In Problems 73 and 74, find parametric equations for the line, through the indicated point that is parallel to the given planes., x � y � 4z � 2, 2x � y � z � 10; (5, 6, �12), 74. 2x �, z�0, �x � 3y � z � 1; (�3, 5, �1), 73., , In Problems 75 and 76, find an equation of the plane that contains the given line and is orthogonal to the indicated plane., 75. x � 4 � 3t, y � �t, z � 1 � 5t; x � y � z � 7, 76., , y�2, 22x, z28, �, �, ; 2x � 4y � z � 16 � 0, 3, 5, 2, , In Problems 77–82, graph the given equation., 77. 5x � 2y � z � 10, 79. �y � 3z � 6 � 0, 81. �x � 2y � z � 4, , 78. 3x � 2z � 9, 80. 3x � 4y � 2z � 12 � 0, 82. x � y � 1 � 0, , Vector Spaces, , INTRODUCTION In the preceding sections we were dealing with points and vectors in 2- and, , 3-space. Mathematicians in the nineteenth century, notably the English mathematicians Arthur, Cayley (1821–1895) and James Joseph Sylvester (1814–1897) and the Irish mathematician, William Rowan Hamilton (1805–1865), realized that the concepts of point and vector could, be generalized. A realization developed that vectors could be described, or defined, by analytic, rather than geometric properties. This was a truly significant breakthrough in the history of, mathematics. There is no need to stop with three dimensions; ordered quadruples �a1, a2, a3, a4�,, quintuples �a1, a2, a3, a4, a5�, and n-tuples �a1, a2, … , an� of real numbers can be thought of as, vectors just as well as ordered pairs �a1, a2� and ordered triples �a1, a2, a3�; the only difference, being that we lose our ability to visualize directed line segments or arrows in 4-dimensional,, 5-dimensional, or n-dimensional space., 7.6 Vector Spaces, , |, , 351

Page 131 :

n-Space In formal terms, a vector in n-space is any ordered n-tuple a � �a1, a2, … , an � of, real numbers called the components of a. The set of all vectors in n-space is denoted by R n. The, concepts of vector addition, scalar multiplication, equality, and so on, listed in Definition 7.2.1, carry over to R n in a natural way. For example, if a � �a1, a2, … , an � and b � �b1, b2, … , bn �,, then addition and scalar multiplication in n-space are defined by, a � b � �a1 � b1, a2 � b2, … , an � bn �, , ka � �ka1, ka2, … , kan �., , and, , (1), , The zero vector in R n is 0 � �0, 0, … , 0�. The notion of length or magnitude of a vector, a � �a1, a2, … , an� in n-space is just an extension of that concept in 2- and 3-space:, iai � "a 21 � a 22 � p � a 2n ., The length of a vector is also called its norm. A unit vector is one whose norm is 1. For a nonzero, vector a, the process of constructing a unit vector u by multiplying a by the reciprocal, 1, of its norm, that is, u �, a, is referred to as normalizing a. For example, if a � �3, 1, 2, �1�,, iai, then iai � "32 � 12 � 22 � (�1)2 � "15 and a unit vector is, u�, , 1, "15, , a� h, , 3, , ,, , 1, , ,, , 2, , "15 "15 "15, , ,�, , 1, "15, , i., , The standard inner product, also known as the Euclidean inner product or dot product,, of two n-vectors a � �a1, a2, … , an� and b � �b1, b2, … , bn� is the real number defined by, a b � �a1, a2, … , an� �b1, b2, … , bn� � a1b1 � a2b2 �, , � anbn., , (2), , Two nonzero vectors a and b in R n are said to be orthogonal if and only if a b � 0. For, example, a � �3, 4, 1, �6� and b � �1, 12 , 1, 1� are orthogonal in R 4 since a b � 3 1 � 4 12 �, 1 1 � (�6) 1 � 0., , Vector Space We can even go beyond the notion of a vector as an ordered n-tuple in Rn. A, , vector can be defined as anything we want it to be: an ordered n-tuple, a number, an array of numbers,, or even a function. But we are particularly interested in vectors that are elements in a special kind, of set called a vector space. Fundamental to the notion of vector space are two kinds of objects,, vectors and scalars, and two algebraic operations analogous to those given in (1). For a set of vectors we want to be able to add two vectors in this set and get another vector in the same set, and we, want to multiply a vector by a scalar and obtain a vector in the same set. To determine whether a, set of objects is a vector space depends on whether the set possesses these two algebraic operations, along with certain other properties. These properties, the axioms of a vector space, are given next., Definition 7.6.1, , Vector Space, , Let V be a set of elements on which two operations called vector addition and scalar multiplication, are defined. Then V is said to be a vector space if the following 10 properties are satisfied., Axioms for Vector Addition:, (i) If x and y are in V, then x � y is in V., (ii) For all x, y in V, x � y � y � x., (iii) For all x, y, z in V, x � (y � z) � (x � y) � z., (iv) There is a unique vector 0 in V such that, 0 � x � x � 0 � x., (v) For each x in V, there exists a vector �x such that, x � (�x) � (�x) � x � 0., Axioms for Scalar Multiplication:, (vi) If k is any scalar and x is in V, then kx is in V., (vii) k(x � y) � kx � ky, (viii) (k1 � k2)x � k1x � k2x, (ix) k1(k2x) � (k1k2)x, (x) 1x � x, , 352, , |, , CHAPTER 7 Vectors, , d commutative law, d associative law, d zero vector, d negative of a vector, , d distributive law, d distributive law

Page 132 :

In this brief introduction to abstract vectors we shall take the scalars in Definition 7.6.1 to be, real numbers. In this case V is referred to as a real vector space, although we shall not belabor this, term. When the scalars are allowed to be complex numbers we obtain a complex vector space., Since properties (i)–(viii) on page 352 are the prototypes for the axioms in Definition 7.6.1, it is, clear that R2 is a vector space. Moreover, since vectors in R3 and R n have these same properties,, we conclude that R3 and R n are also vector spaces. Axioms (i) and (vi) are called the closure, axioms and we say that a vector space V is closed under vector addition and scalar multiplication., Note, too, that concepts such as length and inner product are not part of the axiomatic structure, of a vector space., EXAMPLE 1, , Checking the Closure Axioms, , Determine whether the sets (a) V � {1} and (b) V � {0} under ordinary addition and multiplication by real numbers are vector spaces., SOLUTION (a) For this system consisting of one element, many of the axioms given in, Definition 7.6.1 are violated. In particular, axioms (i) and (vi) of closure are not satisfied., Neither the sum 1 � 1 � 2 nor the scalar multiple k � 1 � k, for k � 1, is in V. Hence V is, not a vector space., (b) In this case the closure axioms are satisfied since 0 � 0 � 0 and k � 0 � 0 for any real, number k. The commutative and associative axioms are satisfied since 0 � 0 � 0 � 0 and, 0 � (0 � 0) � (0 � 0) � 0. In this manner it is easy to verify that the remaining axioms are, also satisfied. Hence V is a vector space., The vector space V � {0} is often called the trivial or zero vector space., If this is your first experience with the notion of an abstract vector, then you are cautioned, to not take the names vector addition and scalar multiplication too literally. These operations, are defined and as such you must accept them at face value even though these operations may, not bear any resemblance to the usual understanding of ordinary addition and multiplication in,, say, R, R 2, R 3, or R n. For example, the addition of two vectors x and y could be x � y. With this, forewarning, consider the next example., EXAMPLE 2, , An Example of a Vector Space, , Consider the set V of positive real numbers. If x and y denote positive real numbers, then we, write vectors in V as x � x and y � y. Now, addition of vectors is defined by, x � y � xy, and scalar multiplication is defined by, kx � x k., Determine whether V is a vector space., SOLUTION We shall go through all ten axioms in Definition 7.6.1., For x � x � 0 and y � y � 0, x � y � xy � 0. Thus, the sum x � y is in V; V is, closed under addition., (ii) Since multiplication of positive real numbers is commutative, we have for all, x � x and y � y in V, x � y � xy � yx � y � x. Thus, addition is commutative., (iii) For all x � x, y � y, z � z in V,, , (i), , x � (y � z) � x(yz) � (xy)z � (x � y) � z., Thus, addition is associative., (iv) Since 1 � x � 1x � x � x and x � 1 � x1 � x � x, the zero vector 0 is 1 � 1., 1, (v) If we define �x � , then, x, 1, 1, x � (�x) � x � 1 � 1 � 0 and (�x) � x � x � 1 � 1 � 0., x, x, Therefore, the negative of a vector is its reciprocal., 7.6 Vector Spaces |, , 353

Page 133 :

(vi) If k is any scalar and x � x � 0 is any vector, then k x � x k � 0. Hence V is closed, under scalar multiplication., (vii) If k is any scalar, then, k(x � y) � (xy)k � xk yk � kx � ky., (viii) For scalars k1 and k2,, (k1 � k2)x � x (k1 � k2) � x k1 x k2 � k1x � k2x., (ix) For scalars k1 and k2,, k1(k2x) � (x k2)k1 � x k1 k2 � (k1k2)x., (x) 1x � x1 � x � x., Since all the axioms of Definition 7.6.1 are satisfied, we conclude that V is a vector space., Here are some important vector spaces—we have mentioned some of these previously. The, operations of vector addition and scalar multiplication are the usual operations associated with, the set., •, •, •, •, •, •, •, •, •, •, , The set R of real numbers, The set R2 of ordered pairs, The set R3 of ordered triples, The set R n of ordered n-tuples, The set Pn of polynomials of degree less than or equal to n, The set P of all polynomials, The set of real-valued functions f defined on the entire real line, The set C[a, b] of real-valued functions f continuous on the closed interval [a, b], The set C(�q , q ) of real-valued functions f continuous on the entire real line, The set C n [a, b] of all real-valued functions f for which f, f �, f �, … , f (n) exist and are, continuous on the closed interval [a, b], , Subspace It may happen that a subset of vectors W of a vector space V is itself a vector, , space., , Definition 7.6.2, , Subspace, , If a subset W of a vector space V is itself a vector space under the operations of vector addition, and scalar multiplication defined on V, then W is called a subspace of V., Every vector space V has at least two subspaces: V itself and the zero subspace {0}; {0} is a, subspace since the zero vector must be an element in every vector space., To show that a subset W of a vector space V is a subspace, it is not necessary to demonstrate, that all ten axioms of Definition 7.6.1 are satisfied. Since all the vectors in W are also in V, these, vectors must satisfy axioms such as (ii) and (iii). In other words, W inherits most of the properties of a vector space from V. As the next theorem indicates, we need only check the two closure, axioms to demonstrate that a subset W is a subspace of V., Theorem 7.6.1, , Criteria for a Subspace, , A nonempty subset W of a vector space V is a subspace of V if and only if W is closed under, vector addition and scalar multiplication defined on V:, (i) If x and y are in W, then x � y is in W., (ii) If x is in W and k is any scalar, then k x is in W., , EXAMPLE 3, , A Subspace, , Suppose f and g are continuous real-valued functions defined on the entire real line. Then we, know from calculus that f � g and k f, for any real number k, are continuous and real-valued, functions. From this we can conclude that C(� q , q ) is a subspace of the vector space of, real-valued functions defined on the entire real line., 354, , |, , CHAPTER 7 Vectors

Page 134 :

EXAMPLE 4, , A Subspace, , The set Pn of polynomials of degree less than or equal to n is a subspace of C(� q , q ), the, set of real-valued functions continuous on the entire real line., It is always a good idea to have concrete visualizations of vector spaces and subspaces. The, subspaces of the vector space R3 of three-dimensional vectors can be easily visualized by thinking of a vector as a point (a1, a2, a3). Of course, {0} and R 3 itself are subspaces; other subspaces, are all lines passing through the origin, and all planes passing through the origin. The lines and, planes must pass through the origin since the zero vector 0 � (0, 0, 0) must be an element in, each subspace., Similar to Definition 3.1.1 we can define linearly independent vectors., Definition 7.6.3, , Linear Independence, , A set of vectors {x1, x2, … , xn} is said to be linearly independent if the only constants satisfying the equation, k1x1 � k2x2 �, , (3), , � kn x n � 0, , are k1 � k2 �, � kn � 0. If the set of vectors is not linearly independent, then it is said to, be linearly dependent., In R3, the vectors i � �1, 0, 0�, j � �0, 1, 0�, and k � �0, 0, 1� are linearly independent since, the equation k1i � k2 j � k3k � 0 is the same as, k1�1, 0, 0� � k2�0, 1, 0� � k3�0, 0, 1� � �0, 0, 0�, , or, , �k1, k2, k3� � �0, 0, 0�., , By equality of vectors, (iii) of Definition 7.2.1, we conclude that k1 � 0, k2 � 0, and k3 � 0. In, Definition 7.6.3, linear dependence means that there are constants k1, k2, … , kn not all zero such, that k1x1 � k2x2 � � knxn � 0. For example, in R3 the vectors a � �1, 1, 1�, b � �2, �1, 4�,, and c � �5, 2, 7� are linearly dependent since (3) is satisfied when k1 � 3, k2 � 1, and k3 � �1:, 3�1, 1, 1� � �2, �1, 4� � �5, 2, 7� � �0, 0, 0�, , or, , 3a � b � c � 0., , We observe that two vectors are linearly independent if neither is a constant multiple of the, other., , Basis Any vector in R 3 can be written as a linear combination of the linearly independent, , vectors i, j, and k. In Section 7.2, we said that these vectors form a basis for the system of threedimensional vectors., Definition 7.6.4, , Basis for a Vector Space, , Consider a set of vectors B � {x1, x2, … , xn} in a vector space V. If the set B is linearly, independent and if every vector in V can be expressed as a linear combination of these vectors,, then B is said to be a basis for V., , Standard Bases Although we cannot prove it in this course, every vector space has a basis., The vector space Pn of all polynomials of degree less than or equal to n has the basis {1, x, x2, … , xn}, since any vector (polynomial) p(x) of degree n or less can be written as the linear combination, p(x) � cnxn � � c2x2 � c1x � c0. A vector space may have many bases. We mentioned previously the set of vectors {i, j, k} is a basis for R 3. But it can be proved that {u1, u2, u3}, where, u1 � �1, 0, 0�,, , u2 � �1, 1, 0�,, , u3 � �1, 1, 1�, , is a linearly independent set (see Problem 23 in Exercises 7.6) and, furthermore, every vector, a � �a1, a2, a3� can be expressed as a linear combination a � c1u1 � c2u2 � c3u3. Hence, the set, of vectors {u1, u2, u3} is another basis for R3. Indeed, any set of three linearly independent vectors is a basis for that space. However, as mentioned in Section 7.2, the set {i, j, k} is referred to, as the standard basis for R3. The standard basis for the space Pn is {1, x, x2, … , xn}. For the, 7.6 Vector Spaces, , |, , 355

Page 135 :

vector space R n, the standard basis consists of the n vectors, e1 � �1, 0, 0, … , 0�, e2 � �0, 1, 0, … , 0�, … , en � �0, 0, 0, … , 1�., , (4), , If B is a basis for a vector space V, then for every vector v in V there exist scalars ci, i � 1, 2, . . . , n, such that, v � c1x2 � c2x2 � p � cnxn., (5), Read the last sentence, several times., , The scalars ci , i � 1, 2, … , n, in the linear combination (5) are called the coordinates of v relative, to the basis B. In R n, the n-tuple notation �a1, a2, … , an� for a vector a means that real numbers, a1, a2, … , an are the coordinates of a relative to the standard basis with ei’s in the precise order, given in (4)., , Dimension If a vector space V has a basis B consisting of n vectors, then it can be proved, that every basis for that space must contain n vectors. This leads to the next definition., Definition 7.6.5, , Dimension of a Vector Space, , The number of vectors in a basis B for a vector space V is said to be the dimension of the, space., , Dimensions of Some Vector Spaces, , EXAMPLE 5, , (a) In agreement with our intuition, the dimensions of the vector spaces R, R 2, R 3, and R n, are, in turn, 1, 2, 3, and n., (b) Since there are n � 1 vectors in the standard basis B � {1, x, x2, … , x n}, the dimension, of the vector space Pn of polynomials of degree less than or equal to n is n � 1., (c) The zero vector space {0} is given special consideration. This space contains only 0, and since {0} is a linearly dependent set, it is not a basis. In this case it is customary to take, the empty set as the basis and to define the dimension of {0} as zero., If the basis of a vector space V contains a finite number of vectors, then we say that the vector, space is finite dimensional; otherwise it is infinite dimensional. The function space C n (I ) of n, times continuously differentiable functions on an interval I is an example of an infinite-dimensional, vector space., , Linear Differential Equations Consider the homogeneous linear nth-order differential, , equation, , an(x), , d ny, d n 2 1y, dy, �, a, (x), � p � a1(x), � a0(x)y � 0, n21, n, n21, dx, dx, dx, , (6), , on an interval I on which the coefficients are continuous and an(x) � 0 for every x in the interval., A solution y1 of (6) is necessarily a vector in the vector space C n (I). In addition, we know from, the theory examined in Section 3.1 that if y1 and y2 are solutions of (6), then the sum y1 � y2 and, any constant multiple ky1 are also solutions. Since the solution set is closed under addition and, scalar multiplication, it follows from Theorem 7.6.1 that the solution set of (6) is a subspace of, C n (I ). Hence the solution set of (6) deserves to be called the solution space of the differential, equation. We also know that if {y1, y2, … , yn} is a linearly independent set of solutions of (6),, then its general solution of the differential equation is the linear combination, y � c1y1(x) � c2 y2(x) � p � cn yn(x)., Recall that any solution of the equation can be found from this general solution by specialization, of the constants c1, c2, … , cn. Therefore, the linearly independent set of solutions {y1, y2, … , yn}, is a basis for the solution space. The dimension of this solution space is n., EXAMPLE 6, , Dimension of a Solution Space, , The general solution of the homogeneous linear second-order differential equation y� � 25y � 0, is y � c1 cos 5x � c2 sin 5x. A basis for the solution space consists of the linearly independent, vectors {cos 5x, sin 5x}. The solution space is two-dimensional., 356, , |, , CHAPTER 7 Vectors

Page 136 :

The set of solutions of a nonhomogeneous linear differential equation is not a vector space. Several, axioms of a vector space are not satisfied; most notably the set of solutions does not contain a zero, vector. In other words, y � 0 is not a solution of a nonhomogeneous linear differential equation., , Span If S denotes any set of vectors {x1, x2, … , xn} in a vector space V, then the set of all, linear combinations of the vectors x1, x2, … , xn in S,, {k1x1 � k2x2 � p � knxn},, where the ki, i � 1, 2, … , n are scalars, is called the span of the vectors and written Span(S), or Span(x1, x2, … , xn). It is left as an exercise to show that Span(S) is a subspace of the vector, space V. See Problem 33 in Exercises 7.6. Span(S) is said to be a subspace spanned by the vectors, x1, x2, … , xn. If V � Span(S), then we say that S is a spanning set for the vector space V, or that, S spans V. For example, each of the three sets, {i, j, k},, , {i, i � j, i � j � k},, , and, , {i, j, k, i � j, i � j � k}, , are spanning sets for the vector space R 3. But note that the first two sets are linearly independent,, whereas the third set is dependent. With these new concepts we can rephrase Definitions 7.6.4, and 7.6.5 in the following manner:, A set S of vectors {x1, x2, … , xn} in a vector space V is a basis for V if S is linearly, independent and is a spanning set for V. The number of vectors in this spanning set S is, the dimension of the space V., , REMARKS, (i) Suppose V is an arbitrary real vector space. If there is an inner product defined on V it need not, look at all like the standard or Euclidean inner product defined on Rn. In Chapter 12 we will work, with an inner product that is a definite integral. We shall denote an inner product that is not the, Euclidean inner product by the symbol (u, v). See Problems 30, 31, and 38(b) in Exercises 7.6., (ii) A vector space V on which an inner product has been defined is called an inner product, space. A vector space V can have more than one inner product defined on it. For example, a, non-Euclidean inner product defined on R2 is (u, v) � u1v1 � 4u2v2, where u � �u1, u2� and, v � �v1, v2�. See Problems 37 and 38(a) in Exercises 7.6., (iii) A lot of our work in the later chapters in this text takes place in an infinite-dimensional, vector space. As such, we need to extend the definition of linear independence of a finite set, of vectors S � {x1, x2, … , xn} given in Definition 7.6.3 to an infinite set:, An infinite set of vectors S � {x1, x2, …} is said to be linearly independent if every, finite subset of the set S is linearly independent. If the set S is not linearly independent,, then it is linearly dependent., We note that if S contains a linearly dependent subset, then the entire set S is linearly dependent., The vector space P of all polynomials has the standard basis B � {1, x, x 2, …}. The infinite, set B is linearly independent. P is another example of an infinite-dimensional vector space., , 7.6, , Exercises, , Answers to selected odd-numbered problems begin on page ANS-15., , In Problems 1–10, determine whether the given set is a vector, space. If not, give at least one axiom that is not satisfied. Unless, stated to the contrary, assume that vector addition and scalar, multiplication are the ordinary operations defined on that set., 1. The set of vectors �a1, a2�, where a1 � 0, a2 � 0, 2. The set of vectors �a1, a2�, where a2 � 3a1 � 1, 3. The set of vectors �a1, a2�, scalar multiplication defined by, , k�a1, a2� � �ka1, 0�, , 4. The set of vectors �a1, a2�, where a1 � a2 � 0, 5. The set of vectors �a1, a2, 0�, 6. The set of vectors �a1, a2�, addition and scalar multiplication, , defined by, , �a1, a2� � �b1, b2� � �a1 � b1 � 1, a2 � b2 � 1�, k�a1, a2� � �ka1 � k � 1, ka2 � k � 1�, 7. The set of real numbers, addition defined by x � y � x � y, , 7.6 Vector Spaces, , |, , 357

Page 137 :

8. The set of complex numbers a � bi, where i 2 � �1, addition, , and scalar multiplication defined by, k(a � bi) � ka � kbi, k a real number, , a, , a11, a21, , a12, b11, b � a, a22, b21, ka, , a12, b , addition and, a22, , b12, a12 � b12, b � a, b22, a22 � b22, a12, ka11, b � a, a22, ka21, , a11, a21, , x, is a vector in C[0, 3] but, x 2 � 4x � 3, not a vector in C[�3, 0]., , 29. Explain why f (x) �, , (a1 � b1i) � (a2 � b2i) � (a1 � a2) � (b1 � b2)i, a11, 9. The set of arrays of real numbers a, a21, scalar multiplication defined by, , 28. 1, (x � 1), (x � 1)2, x 2 in P2, , a11 � b11, b, a21 � b21, , ka12, b, ka22, , 10. The set of all polynomials of degree 2, , In Problems 11–16, determine whether the given set is a, subspace of the vector space C(�q , q )., , 30. A vector space V on which a dot or inner product has been, , defined is called an inner product space. An inner product, for the vector space C[a, b] is given by, ( f, g) �, , 13. All nonnegative functions f, 14. All functions f such that f (�x) � f (x), 15. All differentiable functions f, 16. All functions f of the form f (x) � c1ex � c2xex, , In Problems 17–20, determine whether the given set is, a subspace of the indicated vector space., 17. Polynomials of the form p(x) � c3x3 � c1x; P3, 18. Polynomials p that are divisible by x � 2; P2, , In C[0, 2p] compute (x, sin x)., 31. The norm of a vector in an inner product space is defined in, terms of the inner product. For the inner product given in, Problem 30, the norm of a vector is given by i f i � !( f, f )., In C[0, 2p] compute ixi and isin xi., 32. Find a basis for the solution space of, d 4y, d 3y, d 2y, 2, 2, �, 10, � 0., dx 4, dx 3, dx 2, 33. Let {x1, x2, … , xn} be any set of vectors in a vector space V., , Show that Span(x1, x2, … , xn) is a subspace of V., , Discussion Problems, 34. Discuss: Is R 2 a subspace of R 3? Are R 2 and R 3 subspaces, , of R 4?, 35. In Problem 9, you should have proved that the set M22 of, 2 2 arrays of real numbers, , 19. All unit vectors; R3, 20. Functions f such that, , eba, , S � {(x, y, z) Z x � at, y � bt, z � ct, a, b, c real numbers}., With addition and scalar multiplication the same as for vectors, �x, y, z �, show that S is a subspace of R 3., 22. In 3-space, a plane through the origin can be written as, S � {(x, y, z ) | ax � by � cz � 0, a, b, c real numbers}. Show, that S is a subspace of R3., 23. The vectors u1 � �1, 0, 0�, u2 � �1, 1, 0�, and u3 � �1, 1, 1�, form a basis for the vector space R 3., (a) Show that u1, u2, and u3 are linearly independent., (b) Express the vector a � �3, �4, 8� as a linear combination, of u1, u2, and u3., 24. The vectors p1(x) � x � 1, p2(x) � x � 1 form a basis for the, vector space P1., (a) Show that p1(x) and p2(x) are linearly independent., (b) Express the vector p(x) � 5x � 2 as a linear combination, of p1(x) and p2(x)., In Problems 25–28, determine whether the given vectors are, linearly independent or linearly dependent., 25. �4, �8�, ��6, 12� in R 2, 26. �1, 1�, �0, 1�, �2, 5� in R 2, 27. 1, (x � 1), (x � 1)2 in P2, , 358, , |, , M22 � e a, , f(x) dx � 0; C[a, b], , 21. In 3-space, a line through the origin can be written as, , CHAPTER 7 Vectors, , f (x)g(x) dx., , a, , 11. All functions f such that f (1) � 0, 12. All functions f such that f (0) � 1, , #, , b, , a11, a21, , a12, b f,, a22, , or matrices, is a vector space with vector addition and scalar, multiplication defined in that problem. Find a basis for M22., What is the dimension of M22?, 36. Consider a finite orthogonal set of nonzero vectors, {v1, v2, … , vk} in R n. Discuss: Is this set linearly independent, or linearly dependent?, 37. If u, v, and w are vectors in a vector space V, then the axioms, of an inner product (u, v) are, (i), (ii), (iii), (iv), , (u, v) � (v, u), (k u, v) � k(u, v), k a scalar, (u, u) � 0 if u � 0 and (u, u) � 0 if u � 0, (u, v � w) � (u, v) � (u, w)., , Show that (u, v) � u1v1 � 4u2v2, where u � �u1, u2� and, v � �v1, v2�, is an inner product on R2., 38. (a) Find a pair of nonzero vectors u and v in R2 that are not, , orthogonal with respect to the standard or Euclidean inner, product u v, but are orthogonal with respect to the inner, product (u, v) in Problem 37., (b) Find a pair of nonzero functions f and g in C[0, 2p] that, are orthogonal with respect to the inner product ( f, g), given in Problem 30.

Page 138 :

7.7, , Gram–Schmidt Orthogonalization Process, , INTRODUCTION In Section 7.6 we saw that a vector space V can have many different bases., Recall, the defining characteristics of any basis B � {x1, x2, … , xn} of a vector space V is that, , • the set B is linearly independent, and, • the set B spans the space., In this context the word span means that every vector in the space can be expressed as a linear, combination of the vectors x1, x2, … , xn. For example, every vector u in R n can be written as a, linear combination of the vectors in the standard basis B � {e1, e2, … , en}, where, e1 � �1, 0, 0, … , 0�,, , e2 � �0, 1, 0, … , 0�,, , …,, , en � �0, 0, 0, … , 1�., , This standard basis B � {e1, e2, … , en} is also an example of an orthonormal basis; that is, the, ei , i � 1, 2, … , n are mutually orthogonal and are unit vectors; that is,, ei � ej � 0, i � j, , i ei i � 1, i � 1, 2, … , n., , and, , In this section we focus on orthonormal bases for R n and examine a procedure whereby we, can transform or convert any basis B of R n into an orthonormal basis., , Orthonormal Basis for R 3, , EXAMPLE 1, , The set of three vectors, w1 � h, , 1, , ,, , 1, , ,, , 1, , "3 "3 "3, , i, w2 � h�, , 2, , ,, , 1, , ,, , 1, , "6 "6 "6, , i, w3 � h0 ,, , 1, "2, , ,�, , 1, "2, , i, , (1), , is linearly independent and spans the space R 3. Hence B � {w1, w2, w3} is a basis for R 3., Using the standard inner product or dot product defined on R 3, observe, w1 � w2 � 0, w1 � w3 � 0, w2 � w3 � 0,, , and, , i w1 i � 1, i w2 i � 1, i w3 i � 1., , Hence B is an orthonormal basis., A basis B for R n need not be orthogonal nor do the basis vectors need to be unit vectors. In, fact, any linearly independent set of n vectors can serve as a basis for the n-dimensional vector, space R n. For example, it is a straightforward task to show that the vectors, u1 � �1, 0, 0�,, , u2 � �1, 1, 0�,, , u3 � �1, 1, 1�, , in R 3 are linearly independent and hence B � {u1, u2, u3} is a basis for R 3. Note that B is not an, orthogonal basis., Generally, an orthonormal basis for a vector space V turns out to be the most convenient basis, for V. One of the advantages that an orthonormal basis has over any other basis for R n is the, comparative ease with which we can obtain the coordinates of a vector u relative to, that basis., Theorem 7.7.1, , Coordinates Relative to an Orthonormal Basis, , Suppose B � {w1, w2, … , wn} is an orthonormal basis for R n. If u is any vector in R n, then, u � (u � w1)w1 � (u � w2)w2 � p � (u � wn )wn., , PROOF: The vector u is in R n and so it is an element of the set Span(B). In other words, there, , exist real scalars ki, i � 1, 2, … , n such that u can be expressed as the linear combination, u � k1w1 � k2w2 � p � knwn., 7.7 Gram–Schmidt Orthogonalization Process |, , 359

Page 139 :

The scalars ki are the coordinates of u relative to the basis B. These coordinates can be found by, taking the dot product of u with each of the basis vectors:, u wi � (k1w1 � k2w2 � p � knwn) wi � k1(w1 wi) � k2(w2 wi) � p � kn(wn wi). (2), Since B is orthonormal, wi is orthogonal to all vectors in B with the exception of wi itself., That is, wi wj � 0, i � j and wi wi � i wi i 2 � 1. Hence from (2), we obtain ki � (u wi), for i � 1, 2, … , n., , Coordinates of a Vector in R 3, , EXAMPLE 2, , Find the coordinates of the vector u � � 3, �2, 9� relative to the orthonormal basis B for R 3, given in (1) of Example 1. Write u in terms of the basis B., SOLUTION From Theorem 7.7.1, the coordinates of u relative to the basis B in (1) of Example 1, are simply, u w1 �, , 10, "3, , , u w2 �, , 1, "6, , , and u w3 � �, , 11, , ., , "2, , Hence we can write, u�, , u2, , 10, "3, , u1, (a) Linearly independent vectors u1 and u2, , u2, , "6, , w2 2, , 11, "2, , w3 ., , Gram–Schmidt Orthogonalization Process The procedure known as the Gram–, Schmidt orthogonalization process is a straightforward algorithm for generating an orthogonal, basis B � {v1, v2, … , vn} from any given basis B � {u1, u2, … , un} for R n. We then produce an, orthonormal basis B� � {w1, w2, … , wn} by normalizing the vectors in the orthogonal basis B ., The key idea in the orthogonalization process is vector projection, and so we suggest that you, review that concept in Section 7.3. Also, for the sake of gaining some geometric insight into the, process, we shall begin in R 2 and R 3., process for R n is a sequence of steps; at each step we construct a vector vi that is orthogonal to, the vector in the preceding step. The transformation of a basis B � {u1, u2} for R 2 into an orthogonal basis B � {v1, v2} consists of two steps. See FIGURE 7.7.1(a). The first step is simple,, we merely choose one of the vectors in B, say, u1, and rename it v1. Next, as shown in Figure, 7.7.1(b), we project the remaining vector u2 in B onto the vector v1 and define a second vector, u 2 v1, bv . As seen in, to be v2 � u2 � proj v1 u2. Recall from (12) of Section 7.3 that proj v1 u2 � a, v1 v1 1, Figure 7.7.1(c), the vectors, , (b) Projection of u2 onto v1, , u2, v2 = u2 – projv u2, 1, , projv1u2, , 1, , Constructing an Orthogonal Basis for R 2 The Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization, , v1 = u1, , projv1u2, , w1 �, , v1 � u 1, , v1 = u1, , u 2 v1, v2 � u 2 2 a, bv, v1 v1 1, , (c) v1 and v2 are orthogonal, , FIGURE 7.7.1 The orthogonal vectors v1, and v2 are defined in terms of u1 and u2, , (3), , are orthogonal. If you are not convinced of this, we suggest you verify the orthogonality of v1, and v2 by demonstrating that v1 v2 � 0., EXAMPLE 3, , Gram–Schmidt Process in R 2, , The set B � {u1, u2}, where u1 � �3, 1�, u2 � �1, 1�, is a basis for R 2. Transform B into an, orthonormal basis B � � {w1, w2}., SOLUTION We choose v1 as u1: v1 � �3, 1�. Then from the second equation in (3), with, u2 v1 � 4 and v1 v1 � 10, we obtain, v2 � k1, 1l 2, 360, , |, , CHAPTER 7 Vectors, , 4, 1 3, k3, 1l � h� , i., 10, 5 5

Page 142 :

REMARKS, Although we have focused on R n in the foregoing discussion, the orthogonalization process, summarized in (7) of Theorem 7.7.2 holds in all vector spaces V on which an inner product, (u, v) is defined. In this case, we replace the symbol Rn in (7) with the words “an inner product, space V ” and each dot product symbol u � v with (u, v). See Problems 17 and 18 in Exercises 7.7., , Exercises, , 7.7, , Answers to selected odd-numbered problems begin on page ANS-16., , In Problems 1 and 2, verify that the basis B for the given vector, space is orthonormal. Use Theorem 7.7.1 to find the coordinates, of the vector u relative to the basis B. Then write u as a linear, combination of the basis vectors., 1. B � e h, 2. B � e h, , h�, , 2, , ,, , 5, 12 5, 12, , i, h , � i f ,, 13 13, 13, 13, 1, , 1, , 1, , R 2; u � k4 , 2l, 1, , 1, , ,, ,�, i, h0 , �, ,�, i,, "3 "3, "3, "2, "2, 1, , ,�, , "6 "6, , 1, "6, , 15. u1 � �1, �1, 1, �1�, u2 � �1, 3, 0, 1�, 16. u1 � �4, 0, 2, �1�, u2 � �2, 1, �1, 1�, u3 � �1, 1, �1, 0�, , In Problems 17 and 18, an inner product defined on the vector, space P2 of all polynomials of degree less than or equal to 2, is, given by, , i r , R 3; u � k5 , �1 , 6l, , In Problems 3 and 4, verify that the basis B for the given vector, space is orthogonal. Use Theorem 7.7.1 as an aid in finding the, coordinates of the vector u relative to the basis B. Then write, u as a linear combination of the basis vectors., 3. B � {�1, 0, 1�, �0, 1, 0�, ��1, 0, 1�, R3;, , u � �10, 7, �13�, , 4. B � {�2, 1, �2, 0�, �1, 2, 2, 1�, �3, �4, 1, 3�, �5, �2, 4, �9�}, R4;, , u � �1, 2, 4, 3�, , In Problems 5�8, use the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization, process (3) to transform the given basis B � {u1, u2} for R2 into, an orthogonal basis B� � {v1, v2}. Then form an orthonormal, basis B� � {w1, w2}., (a) First construct B� using v1, u1., (b) Then construct B� using v1, u2., (c) Sketch B and each basis B�., 5. B � {��3, 2�, ��1, �1�} 6. B � {��3, 4�, ��1, 0�}, 7. B � {�1, 1�, �1, 0�}, 8. B � {�5, 7�, �1, �2�}, , In Problems 9–12, use the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization, process (4) to transform the given basis B � {u1, u2, u3} for R3, into an orthogonal basis B� � {v1, v2, v3}. Then form an orthonormal basis B� � {w1, w2, w3}., 9., 10., 11., 12., , In Problems 15 and 16, the given vectors span a subspace W, of R 4. Use the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization process to, construct an orthonormal basis for the subspace., , B � {�1, 1, 0�, �1, 2, 2�, �2, 2, 1�}, B � {��3, 1, 1�, �1, 1, 0�, ��1, 4, 1�}, B � {� 12 , 12 , 1�, ��1, 1, � 12 �, ��1, 12 , 1�}, B � {�1, 1, 1�, �9, �1, 1�, ��1, 4, �2�}, , In Problems 13 and 14, the given vectors span a subspace W, of R 3. Use the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization process to, construct an orthonormal basis for the subspace., 13. u1 � �1, 5, 2�, u2 � ��2, 1, 1�, 14. u1 � �1, 2, 3�, u2 � �3, 4, 1�, , ( p, q) �, , #, , 1, , p(x) q(x) dx., , �1, , Use the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization process to transform, the given basis B for P2 into an orthogonal basis B�., 17. B � {1, x, x2}, 18. B � {x2 � x, x2 � 1, 1 � x2}, , For the inner product (p, q) defined on P2 in Problems 17, and 18, the norm ip(x)i of a polynomial p is defined by, ip(x)i2 � ( p, p) �, , #, , 1, , p2(x) dx., , �1, , Use this norm in Problems 19 and 20., 19. Construct an orthonormal basis B� from B� obtained in, , Problem 17., 20. Construct an orthonormal basis B� from B� obtained in, , Problem 18., In Problems 21 and 22, let p(x) � 9x2 � 6x � 5 be a vector, in P2. Use Theorem 7.7.1 and the indicated orthonormal basis B�, to find the coordinates p(x) relative to B�. Then write p(x) as a, linear combination of the basis vectors., 21. B� in Problem 19, , 22. B� in Problem 20, , Discussion Problem, 23. The set of vectors {u1, u2, u3}, where, , u1 � �1, 1, 3�, u2 � � 1, 4, 1�, and u3 � � 1, 10, �3�,, is linearly dependent in R3 since u3 � �2u1 � 3u2. Discuss, what you would expect when the Gram–Schmidt process in (4), is applied to these vectors. Then carry out the orthogonalization, process., 7.7 Gram–Schmidt Orthogonalization Process |, , 363

Page 143 :

Chapter in Review, , 7, , Answers to selected odd-numbered problems begin on page ANS-16., , Answer Problems 1–30 without referring back to the text. Fill in, the blank or answer true/false., , 29. The distance from the plane y � �5 to the point (4, �3, 1), , 1. The vectors ��4, �6, 10� and ��10, �15, 25� are parallel., , 30. The vectors �1, 3, c� and ��2, �6, 5� are parallel for c � _____, , 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23., 24., 25., 26., 27., 28., , _____, In 3-space, any three distinct points determine a plane., _____, The line x � 1 � 5t, y � 1 � 2t, z � 4 � t and the plane, 2x � 3y � 4z � 1 are perpendicular. _____, Nonzero vectors a and b are parallel if a � b � 0. _____, If the angle between a and b is obtuse, a � b � 0. _____, If a is a unit vector, then a � a � 1. _____, The cross product of two vectors is not commutative., _____, The terminal point of the vector a � b is at the terminal point, of a. _____, (a � b) � c � a � (b � c) _____, If a, b, c, and d are nonzero coplanar vectors, then, (a � b) � (c � d) � 0. _____, The sum of 3i � 4j � 5k and 6i � 2j � 3k is _____ ., If a � b � 0, the nonzero vectors a and b are _____ ., (�k) � (5j) � _____, i � (i � j) � _____, i �12i � 4j � 6k i � _____, i j, k, 5 3 � _____, 32 1, 0 4 �1, A vector that is normal to the plane �6x � y � 7z � 10 � 0, is _____ ., The plane x � 3y � z � 5 contains the point (1, �2, _____ )., The point of intersection of the line x � 1 � ( y � 2)�3 �, (z � 1)�2 and the plane x � 2y � z � 13 is _____., A unit vector that has the opposite direction of a � 4i � 3j � 5k, is _____ ., !, If P1P2 � �3, 5, �4� and P1 has coordinates (2, 1, 7), then the, coordinates of P2 are _____ ., The midpoint of the line segment between P1(4, 3, 10) and, P2(6, �2, �5) has coordinates _____ ., If iai � 7.2, ibi � 10, and the angle between a and b is 135�,, then a � b � _____ ., If a � �3, 1, 0�, b � ��1, 2, 1�, and c � �0, �2, 2�, then, a � (2b � 4c) � _____ ., The x-, y-, and z-intercepts of the plane 2x � 3y � 4z � 24, are, respectively, _____ ., The angle u between the vectors a � i � j and b � i � k, is _____ ., The area of a triangle with two sides given by a � �1, 3, �1�, and b � �2, �1, 2� is _____ ., An equation of the plane containing (3, 6, �2) and with normal, vector n � 3i � k is _____ ., , 364, , |, , CHAPTER 7 Vectors, , is _____ ., and orthogonal for c � _____., 31. Find a unit vector that is perpendicular to both a � i � j and, , b � i � 2j � k., 32. Find the direction cosines and direction angles of the vector, , a � 12 i � 12 j � 14 k., In Problems 33–36, let a � �1, 2, �2� and b � �4, 3, 0�. Find the, indicated number or vector., 33. compb a, 34. proja b, 35. proja (a � b), 36. projb (a � b), 37. Let r be the position vector of a variable point P(x, y, z) in, , 38., , 39., , 40., 41., 42., 43., 44., , 45., , 46., , 47., , space and let a be a constant vector. Determine the surface, described by (a) (r � a) � r � 0 and (b) (r � a) � a � 0., Use the dot product to determine whether the points, (4, 2, �2), (2, 4, �3), and (6, 7, �5) are vertices of a right, triangle., Find symmetric equations for the line through the point, (7, 3, �5) that is parallel to (x � 3)�4 � ( y � 4)�(�2) �, (z � 9)�6., Find parametric equations for the line through the point, (5, �9, 3) that is perpendicular to the plane 8x � 3y � 4z � 13., Show that the lines x � 1 � 2t, y � 3t, z � 1 � t and x � 1 � 2s,, y � �4 � s, z � �1 � s intersect orthogonally., Find an equation of the plane containing the points (0, 0, 0),, (2, 3, 1), (1, 0, 2)., Find an equation of the plane containing the lines x � t,, y � 4t, z � �2t, and x � 1 � t, y � 1 � 4t, z � 3 � 2t., Find an equation of the plane containing (1, 7, �1) that is, perpendicular to the line of intersection of �x � y � 8z � 4, and 3x � y � 2z � 0., A constant force of 10 N in the direction of a � i � j, moves a block on a frictionless surface from P1(4, 1, 0) to, P2(7, 4, 0). Suppose distance is measured in meters. Find the, work done., In Problem 45, find the work done in moving the block between, the same points if another constant force of 50 N in the direction, of b � i acts simultaneously with the original force., Water rushing from a fire hose exerts a horizontal force F1 of, magnitude 200 lb. See FIGURE 7.R.1. What is the magnitude of, the force F3 that a firefighter must exert to hold the hose at an, angle of 45� from the horizontal?, , F2, , F3, , 45°, F1 = 200i, , FIGURE 7.R.1 Fire hose in Problem 47

Page 144 :

48. A uniform ball of weight 50 lb is supported by two frictionless, planes as shown in FIGURE 7.R.2. Let the force exerted by the, , supporting plane �1 on the ball be F1 and the force exerted, by the plane �2 be F2. Since the ball is held in equilibrium,, we must have w � F1 � F2 � 0, where w � �50j. Find the, magnitudes of the forces F1 and F2. [Hint: Assume the forces, F1 and F2 are normal to the planes �1 and �2, respectively,, and act along lines through the center C of the ball. Place the, origin of a two-dimensional coordinate system at C.], , C, F1, , F2, , 1, , 2, , w, 45°, , 30°, , FIGURE 7.R.2 Supported ball in Problem 48, , 49. Determine whether the set of vectors �a1, 0, a3� under addition, , and scalar multiplication defined by, , �a1, 0, a3� � �b1, 0, b3� � �a1 � b1, 0, a3 � b3�, k�a1, 0, a3� � �ka1, 0, a3�, is a vector space., 50. Determine whether the vectors �1, 1, 2�, �0, 2, 3�, and �0, 1, �1�, , are linearly independent in R 3., 51. Determine whether the set of polynomials in Pn satisfying the, condition d 2p/dx2 � 0 is a subspace of Pn. If it is, find a basis, for the subspace., 52. Recall that the intersection of two sets W1 and W2 is the set of, all elements common to both sets, and the union of W1 and, W2 is the set of elements that are in either W1 or W2. Suppose, W1 and W2 are subspaces of a vector space V. Prove, or disprove, by counterexample, the following propositions:, (a) W1 � W2 is a subspace of V., (b) W1 � W2 is a subspace of V., , CHAPTER 7 in Review |, , 365

Page 145 :

P in the spacecraft system after the yaw are related to the, coordinates (x, y, z) of P in the fixed coordinate system by, the equations, , z, , xY � x cos g � y sin g, yY � �x sin g � y cos g, , roll, x, , zY � z, , where, , (a), y, yY, , xY, x, ° yY ¢ � MY ° y ¢, z, zY, , y, , pitch, , where g is the angle of rotation., (a) Verify that the foregoing system of equations can be written as the matrix equation, , cos g, M Y � ° � sin g, 0, , yaw, , P(x, y, z) or P(xY, yY, zY), , xY, , γ, , sin g, cos g, 0, , x, , 0, 0¢., 1, , (b) When the spacecraft performs a pitch, roll, and yaw in, sequence through the angles a, b, and g, respectively,, the final coordinates of the point P in the spacecraft, system (xS, yS, zS) are obtained from the sequence of, transformations, xP � x, xR � xP cos b � zP sin b, yP � y cos a � z sin a, yR � yP, zP � �y sin a � z cos a; zR � xP sin b � zP cos b;, xS � xR cos g � yR sin g, yS � �xR sin g � yR cos g, zS � zR., Write this sequence of transformations as a matrix, equation, xS, x, ° yS ¢ � MYMRMP ° y ¢ ., z, zS, The matrix MY is the same as in part (a). Identify the, matrices MR and MP ., (c) Suppose the coordinates of a point are (1, 1, 1) in the fixed, coordinate system. Determine the coordinates of the point, in the spacecraft system if the spacecraft performs a pitch,, roll, and yaw in sequence through the angles a � 30�,, b � 45�, and g � 60�., , (b), , FIGURE 8.1.2 Spacecraft in Problem 51, 52. Project (a) A matrix A can be partitioned into submatrices., , For example the 3, , 5 and 5, , 2 matrices, , 3, 4, 3 2 �1, 2 4, 0, 7, A � °1 6, 3 �1 5 ¢ , B � • �4, 1μ, 0 4, 6 �2 3, �2 �1, 2, 5, can be written, A� a, , A11, A21, , B, A12, b , B � a 1b ,, A22, B2, , where A11 is the upper left-hand block, or submatrix, indicated, in blue in A, A12 is the upper right-hand block, and so on., Compute the product AB using the partitioned matrices., (b) Investigate how partitioned matrices can be useful when, using a computer to perform matrix calculations involving, large matrices., , 8.2 Systems of Linear Algebraic Equations, INTRODUCTION Recall, any equation of the form ax � by � c, where a, b, and c are real numbers is said to be a linear equation in the variables x and y. The graph of a linear equation in two, variables is a straight line. For real numbers a, b, c, and d, ax � by � cz � d is a linear equation in, the variables x, y, and z and is the equation of a plane in 3-space. In general, an equation of the form, a 1 x1 � a 2 x2 � . . . � a n xn � b n ,, where a1, a2, . . . , an, and bn are real numbers, is a linear equation in the n variables x1, x2, . . . , xn., In this section we will study systems of linear equations. Systems of linear equations are, also called linear systems., 376, , |, , CHAPTER 8 Matrices

Page 146 :

General Form A system of m linear equations in n variables, or unknowns, has the general form, a11x1 � a12x2 � . . . � a1nxn � b1, a21x1 � a22x2 � . . . � a2nxn � b2, o, o, am1x1 � am2x2 � . . . � amnxn � bm ., y, , x, , The coefficients of the variables in the linear system (1) can be abbreviated as aij, where i denotes, the row and j denotes the column in which the coefficient appears. For example, a23 is the coefficient, of the unknown in the second row and third column (that is, x3). Thus, i � 1, 2, 3, . . ., m and j � 1,, 2, 3, . . ., n. The numbers b1, b2, . . ., bm are called the constants of the system. If all the constants are, zero, the system (1) is said to be homogeneous; otherwise it is nonhomogeneous. For example,, this system is homogeneous, , this system is nonhomogeneous, , T, , T, , 5x1 � 9x2 � x3 � 0, x1 � 3x2, �0, 4x1 � 6x2 � x3 � 0, , (a) Consistent, y, , x, , (b) Consistent, , (1), , 2x1 � 5x2 � 6x3 � 1, 4x1 � 3x2 � x3 � 9., , Solution A solution of a linear system (1) is a set of n numbers x1, x2, . . ., xn that satisfies, each equation in the system. For example, x1 � 3, x2 � �1 is a solution of the system, 3x1 � 6x2 � 3, x1 � 4x2 � 7., To see this we replace x1 by 3 and x2 by �1 in each equation:, 3(3) � 6(�1) � 9 � 6 � 3, , y, , x, , (c) Inconsistent, , FIGURE 8.2.1 A linear system of two, equations in two variables interpreted, as lines in 2-space, , and, , 3 � 4(�1) � 3 � 4 � 7., , Solutions of linear systems are also written as an ordered n-tuple (x1, x2, . . ., xn). The solution for, the above system is then the ordered pair (3, �1)., A linear system of equations is said to be consistent if it has at least one solution, and, inconsistent if it has no solutions. If a linear system is consistent, it has either, • a unique solution (that is, precisely one solution), or, • infinitely many solutions., Thus, a system of linear equations cannot have, say, exactly three solutions., For a linear system with two equations and two variables, the lines in the plane, or 2-space,, intersect at one point as in FIGURE 8.2.1(a) (unique solution), are identical as in Figure 8.2.1(b), (infinitely many solutions), or are parallel as in Figure 8.2.1(c) (no solutions)., For a linear system with three equations and three variables, each equation in the system, represents a plane in 3-space. FIGURE 8.2.2 shows some of the many ways that this kind of linear, system can be interpreted., Line of, intersection, , Point of, intersection, , (a) Consistent, , (b) Consistent, , (c) Consistent, No single line, of intersection, , Parallel planes:, No points in, common, , (d) Inconsistent, , (e) Inconsistent, , (f) Inconsistent, , FIGURE 8.2.2 A linear system of three equations in three variables interpreted as planes in 3-space, , 8.2 Systems of Linear Algebraic Equations |, , 377

Page 147 :

EXAMPLE 1, , Verification of a Solution, , Verify that x1 � 14 � 7t, x2 � 9 � 6t, x3 � t, where t is any real number, is a solution of the, system, 2x1 � 3x2 � 4x3 � 1, x1 � x2 � x3 � 5., SOLUTION, , Replacing x1, x2, and x3 in turn by 14 � 7t, 9 � 6t, and t, we have, 2(14 � 7t) � 3(9 � 6t) � 4t � 1, 14 � 7t �, , (9 � 6t) � t � 5., , For each real number t we obtain a different solution of the system; in other words, the, system has an infinite number of solutions. For instance, t � 0, t � 4, and t � �2 give the, three solutions, , and, , x1 � 14,, , x2 � 9,, , x3 � 0,, , x1 � 42,, , x2 � 33,, , x3 � 4,, , x1 � 0,, , x2 � �3,, , x3 � �2,, , respectively. Geometrically, each equation in the system represents a plane in R3. In this, case, the planes intersect in a line as shown in Figure 8.2.2(b). Parametric equations of the, line are x1 � 14 � 7t, x2 � 9 � 6t, x3 � t. The solution can also be written as the ordered, triple (x1, x2, x3) or (14 � 7t, 9 � 6t, t)., , Solving Systems We can transform a system of linear equations into an equivalent, system (that is, one having the same solutions) using the following elementary operations:, (i) Multiply an equation by a nonzero constant., (ii) Interchange the positions of equations in the system., (iii) Add a nonzero multiple of one equation to any other equation., As the next example will show, these elementary operations enable us to systematically eliminate, variables from the equations of the system., EXAMPLE 2, , Solve, , Solving a Linear System, 2x1 � 6x2 � x3 � 7, x1 � 2x2 � x3 � �1, 5x1 � 7x2 � 4x3 � 9., , SOLUTION, , We begin by interchanging the first and second rows:, x1 � 2x2 � x3 � �1, 2x1 � 6x2 � x3 � 7, 5x1 � 7x2 � 4x3 � 9., , Our goal now is to eliminate x1 from the second and third equations. If we add to the second, equation �2 times the first equation, we obtain the equivalent system, x1 � 2x2 � x3 � �1, 2x2 � 3x3 � 9, 5x1 � 7x2 � 4x3 � 9., 378, , |, , CHAPTER 8 Matrices

Page 148 :

By adding to the third equation �5 times the first equation, we get a new equivalent, system:, x1 � 2x2 � x3 � �1, 2x2 � 3x3 � 9, �3x2 � x3 � 14., We are now going to use the second equation to eliminate the variable x2 from the first and, third equations. To simplify matters, let us multiply the second equation by 12 :, x1 � 2x2 �, , x3 � �1, , 3, 9, x 2 � x3 �, 2, 2, �3x2 �, , x3 � 14., , Adding to the first equation �2 times the second equation yields, � 4x3 � �10, , x1, , 3, 9, x 2 � x3 �, 2, 2, �3x2 �, , x3 � 14., , Next, by adding 3 times the second equation to the third equation we get, � 4x3 � �10, , x1, , 3, x 2 � x3 �, 2, 11, x3 �, 2, , 9, 2, 55, ., 2, , We shall use the last equation to eliminate the variable x3 from the first and second equations., To this end, we multiply the third equation by 112 :, � 4x3 � �10, , x1, , 3, 9, x 2 � x3 �, 2, 2, x3 � 5., At this point we could use back-substitution; that is, substitute the value x3 � 5 back into, the remaining equations to determine x1 and x2. However, by continuing with our systematic, elimination, we add to the second equation � 32 times the third equation:, � 4x3 � �10, , x1, x2, , � �3, x3 � 5., , Finally, by adding to the first equation 4 times the third equation, we obtain, � 10, , x1, x2, , � �3, x3 � 5., , 8.2 Systems of Linear Algebraic Equations |, , 379

Page 149 :

It is now apparent that x1 � 10, x2 � �3, x3 � 5 is the solution of the original system. The, answer written as the ordered triple (10, � 3, 5) means that the planes represented by the three, equations in the system intersect at a point as in Figure 8.2.2(a)., , Augmented Matrix Reflecting on the solution of the linear system in Example 2 should, convince you that the solution of the system does not depend on what symbols are used as variables. Thus, the systems, 2x � 6y � z � 7, , 2u � 6v � w � 7, , x � 2y � z � �1, , and, , 5x � 7y � 4z � 9, , u � 2v � w � �1, 5u � 7v � 4w � 9, , have the same solution as the system in Example 2. In other words, in the solution of a linear, system, the symbols used to denote the variables are immaterial; it is the coefficients of the, variables and the constants that determine the solution of the system. In fact, we can solve a, system of form (1) by dropping the variables entirely and performing operations on the rows of, the array of coefficients and constants:, , ±, , a11, a21, , a12, a22, , p, p, , am2, , p, , (, am1, , a1n b1, a2n b2, 4, ≤., (, (, amn bm, , (2), , This array is called the augmented matrix of the system or simply the matrix of the, system (1)., EXAMPLE 3, , Augmented Matrices, , (a) The augmented matrix a, , 1, 4, , 5 2, 2 b represents the linear system, �1 8, , �3, 7, , x1 � 3x2 � 5x3 � 2, 4x1 � 7x2 � x3 � 8., (b) The linear system, x1 � 5x3 � �1, , x1 � 0x2 � 5x3 � �1, , 2x1 � 8x2 � 7, , is the same as, , x2 � 9x3 � 1, , 2x1 � 8x2 � 0x3 � 7, 0x1 � x2 � 9x3 � 1., , Thus the matrix of the system is, 1, °2, 0, , 0, 8, 1, , �5 �1, 0 3 7¢., 9, 1, , Elementary Row Operations Since the rows of an augmented matrix represent the, equations in a linear system, the three elementary operations on a linear system listed previously, are equivalent to the following elementary row operations on a matrix:, (i) Multiply a row by a nonzero constant., (ii) Interchange any two rows., (iii) Add a nonzero multiple of one row to any other row., 380, , |, , CHAPTER 8 Matrices

Page 150 :

Of course, when we add a multiple of one row to another, we add the corresponding entries in, the rows. We say that two matrices are row equivalent if one can be obtained from the other, through a sequence of elementary row operations. The procedure of carrying out elementary row, operations on a matrix to obtain a row-equivalent matrix is called row reduction., , Elimination Methods To solve a system such as (1) using an augmented matrix, we, shall use either Gaussian elimination or the Gauss–Jordan elimination method. In the former, method, we row-reduce the augmented matrix of the system until we arrive at a row-equivalent, augmented matrix in row-echelon form:, (i) The first nonzero entry in a nonzero row is a 1., (ii) In consecutive nonzero rows, the first entry 1 in the lower row appears to the right, of the 1 in the higher row., (iii) Rows consisting of all zeros are at the bottom of the matrix., In the Gauss–Jordan method, the row operations are continued until we obtain an augmented, matrix that is in reduced row-echelon form. A reduced row-echelon matrix has the same three, properties listed previously, but in addition:, (iv) A column containing a first entry 1 has zeros everywhere else., , Echelon Forms, , EXAMPLE 4, , (a) The augmented matrices, 1, °0, 0, , 5, 1, 0, , 0, 2, 0 3 �1 ¢, 0, 0, , and, , a, , 0, 0, , 0, 0, , 1, 0, , �6, 0, , 2 2, 2 b, 1 4, , are in row-echelon form. The reader should verify that the three criteria for this form are, satisfied., (b) The augmented matrices, 1, °0, 0, , 0, 1, 0, , 0, 7, 0 3 �1 ¢, 0, 0, , and, , a, , 0, 0, , 0, 0, , 1, 0, , �6, 0, , 0 �6, b, 2, 1 4, , are in reduced row-echelon form. Note that the remaining entries in the columns that contain, a leading entry 1 are all zeros., , Note: Row operations can, lead to different row-echelon, forms., , It should be noted that in Gaussian elimination, we stop when we have obtained an augmented, matrix in row-echelon form. In other words, by using different sequences of row operations, we, may arrive at different row-echelon forms. This method then requires the use of back-substitution., In Gauss–Jordan elimination, we stop when we have obtained the augmented matrix in reduced, row-echelon form. Any sequence of row operations will lead to the same augmented matrix in, reduced row-echelon form. This method does not require back-substitution; the solution of the, system will be apparent by inspection of the final matrix. In terms of the equations of the original, system, our goal in both methods is simply to make the coefficient of x1 in the first equation*, equal to one and then use multiples of that equation to eliminate x1 from other equations. The, process is repeated for the other variables., To keep track of the row operations used on an augmented matrix, we shall utilize the following notation:, Symbol, , Meaning, , Ri 4 R j, cRi, cRi � Rj, , Interchange rows i and j, Multiply the ith row by the nonzero constant c, Multiply the ith row by c and add to the jth row, , *We can always interchange equations so that the first equation contains the variable x1., , 8.2 Systems of Linear Algebraic Equations |, , 381

Page 151 :

Elimination Methods and Augmented Matrices, , EXAMPLE 5, , Solve the linear system in Example 2 using (a) Gaussian elimination and (b) Gauss–Jordan, elimination., SOLUTION, , (a) Using row operations on the augmented matrix of the system, we obtain:, , �2R1 � R2, �5R1 � R3, , 1, , 3R2 � R3, , 1, , 7, 1, �1 3 �1 ¢, 9, �4, , 2, °1, 5, , 6, 2, 7, , 1, °0, 0, , 2, 2, �3, , 1, °0, 0, , 2, 1, 0, , 1, , 1, °2, 5, , 2, 6, 7, , �1 �1, 1, 2 R2, 33 9¢ 1, 1 14, , 1, °0, 0, , 2, 1, �3, , 1, °0, 0, , 2, 1, 0, , R1 4 R2, , �1 �1, 9, 3, 2 3, 2¢, 11, 2, , 2, 11 R3, , 1, , 55, 2, , �1 �1, 1 3 7¢, 9, �4, �1 �1, 9, 3, 23, 2¢, 1 14, �1 �1, 9, 3, 2 3, 2¢., 1, 5, , The last matrix is in row-echelon form and represents the system, x1 � 2x2 � x3 � �1, x2 �, , 3, 9, x �, 2 3 2, x3 � 5., , Substituting x3 � 5 into the second equation gives x2 � �3. Substituting both these values, back into the first equation finally yields x1 � 10., (b) We start with the last matrix above. Since the first entries in the second and third rows are, ones, we must, in turn, make the remaining entries in the second and third columns zeros:, 1, °0, 0, , 2, 1, 0, , �1 �1, 9, 3, 2 3, 2¢, 1, 5, , 1, °0, 0, , �2R2 � R1, , 1, , 0, 1, 0, , �4 �10, 9, 3, 2 3, 2¢, 1, 5, , �4R3 � R1, �3 R3 � R2, 2, , 1, , 1, °0, 0, , 0, 1, 0, , 0 10, 0 3 �3 ¢, 5, 1, , The last matrix is in reduced row-echelon form. Bearing in mind what the matrix means in, terms of equations, we see that the solution of the system is x1 � 10, x2 � �3, x3 � 5., , Gauss–Jordan Elimination, , EXAMPLE 6, , Use Gauss–Jordan elimination to solve, x1 � 3x2 � 2x3 � �7, 4x1 � x2 � 3x3 � 5, 2x1 � 5x2 � 7x3 � 19., SOLUTION, , Row operations give, 1, °4, 2, 1, , �11 R3, , 1, , 1, °0, 0, , 3, 1, �5, 3, 1, 1, , �2 �7, 3 3 5¢, 7 19, �2 �7, �1 3 �3 ¢, �1 �3, , �4R1 � R2, �2R1 � R3, , 1, °0, 0, , 3, �11, �11, , �3R2 � R1, �R2 � R3, , 1, °0, 0, , 0, 1, 0, , 1, , 1, , �2 �7, 11 3 33 ¢, 11 33, , 1, 2, �1 3 �3 ¢ ., 0, 0, , In this case, the last matrix in reduced row-echelon form implies that the original system, of three equations in three variables is really equivalent to two equations in the variables., 382, , |, , CHAPTER 8 Matrices

Page 152 :

Since only x3 is common to both equations (the nonzero rows), we can assign its values, arbitrarily. If we let x3 � t, where t represents any real number, then we see that the system, has infinitely many solutions: x1 � 2 � t, x2 � �3 � t, x3 � t. Geometrically, these equations are the parametric equations for the line of intersection of the planes x1 � 0x2 � x3 � 2, and 0x1 � x2 � x3 � �3., , EXAMPLE 7, , Inconsistent System, , Solve, , x1 � x 2 � 1, 4x1 � x2 � �6, 2x1 � 3x2 � 8., , SOLUTION In the process of applying Gauss–Jordan elimination to the matrix of the system,, we stop at, 1, °4, 2, , 1, 1, �1 3 �6 ¢, �3, 8, , row, , operations, , 1, , 1, °0, 0, , 0 �1, 1 3 2¢., 0 16, , The third row of the last matrix means 0x1 � 0x2 � 16 (or 0 � 16). Since no numbers x1 and, x2 can satisfy this equation, we conclude that the system has no solution., Worth remembering., , Inconsistent systems of m linear equations in n variables will always yield the situation illustrated, in Example 7; that is, there will be a row in the reduced row-echelon form of the augmented, matrix in which the first n entries are zero and the (n � 1)st entry is nonzero., , Networks The currents in the branches of an electrical network can be determined by, using Kirchhoff’s point and loop rules:, Point rule: The algebraic sum of the currents toward any branch point is 0., Loop rule: The algebraic sum of the potential differences in any loop is 0., , A, , +, –, , E, , i1, , R1, , i2, , i3, , R2, , B, , FIGURE 8.2.3 Electrical network, , R3, , When a loop is traversed in a chosen direction (clockwise or counterclockwise), an emf is taken to, be positive when it is traversed from � to � and negative when traversed from � to �. An iR product is taken to be positive if the chosen direction through the resistor is opposite that of the assumed, current, and negative if the chosen direction is in the same direction as the assumed current., In FIGURE 8.2.3, the branch points of the network are labeled A and B, the loops are labeled L1, and L2, and the chosen direction in each loop is clockwise. Now, applying the foregoing rules to, the network yields the nonhomogeneous system of linear equations, i1 � i 2 � i 3 � 0, , i1, , E � i1R1 � i2R2 � 0, , or, , � i2, , i1R1 � i2R2, , i2R2 � i3R3 � 0, , EXAMPLE 8, , � i3, , �0, (3), , �E, , i2R2 � i3R3 � 0., , Currents in a Network, , Use Gauss–Jordan elimination to solve the system (3) when R1 � 10 ohms, R2 � 20 ohms,, R3 � 10 ohms, and E � 12 volts., SOLUTION, , The system to be solved is, i1 �, , i2 �, , 10i1 � 20i2, , i3 � 0, � 12, , 20i2 � 10i3 � 0., 8.2 Systems of Linear Algebraic Equations |, , 383

Page 153 :

In this case, Gauss–Jordan elimination yields, 1, ° 10, 0, , �1, 20, 20, , �1 0, 0 3 12 ¢, �10 0, , 1, °0, 0, , row, , operations, , 1, , 0, 1, 0, , 0, 03, 1, , 18, 25, 6, 25 ¢ ., 12, 25, , 6, Hence, we see that the currents in the three branches are i1 � 18, 25 � 0.72 ampere, i2 � 25 �, 12, 0.24 ampere, and i3 � 25 � 0.48 ampere., , Homogeneous Systems All the systems in the preceding examples are nonhomogeneous, systems. As we have seen, a nonhomogeneous system can be consistent or inconsistent. By, contrast, a homogeneous system of linear equations, a11x1 � a12x2 � . . . � a1nxn � 0, a12x1 � a22x2 � . . . � a2nxn � 0, o, , (4), , o, , am1x1 � am2x2 � . . . � amnxn � 0, is always consistent, since x1 � 0, x2 � 0, . . ., xn � 0 will satisfy each equation in the system., The solution consisting of all zeros is called the trivial solution. But naturally we are interested, in whether a system of form (4) has any solutions for which some of the xi, i � 1, 2, . . ., n, are, not zero. Such a solution is called a nontrivial solution. A homogeneous system either possesses, only the trivial solution or possesses the trivial solution along with infinitely many nontrivial, solutions. The next theorem, presented without proof, will give us a sufficient condition for the, existence of nontrivial solutions., Theorem 8.2.1, , Existence of Nontrivial Solutions, , A homogeneous system of form (4) possesses nontrivial solutions if the number m of equations is less than the number n of variables (m � n)., EXAMPLE 9, , Solving a Homogeneous System, , Solve, , 2x1 � 4x2 � 3x3 � 0, x1 � x2 � 2x3 � 0., , SOLUTION Since the number of equations is less than the number of variables, we know, from Theorem 8.2.1 that the given system has nontrivial solutions. Using Gauss–Jordan elimination, we find, a, , 2 �4, 3 0, 2 b, 1, 1 �2 0, , R1 4 R2, , 1, , �1 R2, 6, , 1, , a, , 1, 1 �2 0, 2 b, 2 �4, 3 0, , a, , 1 1 �2 0, 2 b, 0 1 �76 0, , �2R1 � R2, , 1, , �R2 � R1, , 1, , a, , a, , 1, 1 �2 0, 2 b, 0 �6, 7 0, , 1 0 �56 0, 2 b., 0 1 �76 0, , As in Example 6, if x3 � t, then the solution of the system is x1 � 56 t, x2 � 76 t, x3 � t. Note we, obtain the trivial solution x1 � 0, x2 � 0, x3 � 0 for this system by choosing t � 0. For t � 0, we get nontrivial solutions. For example, the solutions corresponding to t � 6, t � �12, and, t � 3 are, in turn, x1 � 5, x2 � 7, x3 � 6; x1 � �10, x2 � �14, x3 � �12; and x1 � 52 , x2 � 72 ,, x3 � 3., , Chemical Equations The next example will give an application of homogeneous systems, , in chemistry., 384, , |, , CHAPTER 8 Matrices

Page 155 :

Theorem 8.2.2, , Two Properties of Homogeneous Systems, , Let AX � 0 denote a homogeneous system of linear equations., (i) If X1 is a solution of AX � 0, then so is cX1 for any constant c., (ii) If X1 and X2 are solutions of AX � 0, then so is X1 � X2., , PROOF: (i) Because X1 is a solution, then AX1 � 0. Now, A(cX1) � c(AX1) � c0 � 0., This shows that a constant multiple of a solution of a homogeneous linear system is also, a solution., (ii) Because X1 and X2 are solutions, then AX1 � 0 and AX2 � 0. Now, A(X1 � X2) � AX1 � AX2 � 0 � 0 � 0., This shows that X1 � X2 is a solution., By combining parts (i) and (ii) of Theorem 8.2.2 we can say that if X1 and X2 are solutions, of AX � 0, then so is the linear combination, c1X1 � c2X2,, where c1 and c2 are constants. Moreover, this superposition principle extends to three or more, solutions of AX � 0., EXAMPLE 11, , Example 9 Revisited, , At the end of Example 9, we obtained three distinct solutions, 5, 5, �10, 2, X1 � ° 7 ¢ , X2 � ° �14 ¢ , and X3 � ° 72 ¢, 6, �12, 3, , of the given homogeneous linear system. It follows from the preceding discussion that, 5, �52, 5, �10, 2, 7, X � X1 � X2 � X3 � ° 7 ¢ � ° �14 ¢ � ° 2 ¢ � ° �72 ¢, 3, �3, 6, �12, , is also a solution of the system. Verify this., , Terminology Suppose a linear system has m equations and n variables. If there are more, equations than variables, that is, m � n, then the system is said to be overdetermined. If the, system has fewer equations than variables, that is, m � n, then the system is called underdetermined. An overdetermined linear system may put too many constraints on the variables and so, is usually—not always—inconsistent. The system in Example 7 is overdetermined and is inconsistent. On the other hand an underdetermined system is usually—but not always—consistent., The systems in Examples 9 and 10 are underdetermined and are consistent. It should be noted, that it is impossible for a consistent underdetermined system to possess a single or unique solution. To see this, suppose that m � n. If Gaussian elimination is used to solve the system, then, the row-echelon form that is row equivalent to the matrix of the system will contain r nonzero, rows where r � m � n. Thus we can solve for r of the variables in terms of n � r � 0 variables, or parameters. If the underdetermined system is consistent, then those remaining n � r variables, can be chosen arbitrarily and so the system has an infinite number of solutions., 386, , |, , CHAPTER 8 Matrices

Page 158 :

8.3 Rank of a Matrix, INTRODUCTION In a general m � n matrix,, A� ±, , a11, a21, (, am1, , the rows, , a12, a22, am2, , p, p, p, , u2 � (a21 a22 . . . a2n),, , u1 � (a11 a12 . . . a1n),, , a1n, a2n, (, , ≤, , amn, ...,, , um � (am1 am2 . . . amn), , and columns, v1 � ±, , a11, a21, (, , ≤ , v2 � ±, , am1, , a12, a22, (, , ≤ , p , vn � ±, , am2, , a1n, a2n, (, , ≤, , amn, , are called the row vectors of A and the column vectors of A, respectively., , A Definition As vectors, the set u1, u2, . . . , um is either linearly independent or linearly, dependent. We have the following definition., Definition 8.3.1, , Rank of a Matrix, , The rank of an m � n matrix A, denoted by rank(A), is the maximum number of linearly, independent row vectors in A., EXAMPLE 1, , Rank of a 3 � 4 Matrix, , Find the rank of the 3 � 4 matrix, 1, 1 �1 3, A � ° 2 �2, 6 8¢., 3, 5 �7 8, , (1), , SOLUTION With u1 � (1 1 �1 3), u2 � (2 �2 6 8), and u3 � (3 5 �7 8), we see, that 4u1 � 12 u2 � u3 � 0. In view of Definition 7.6.3 and the discussion following it, we, conclude that the set u1, u2, u3 is linearly dependent. On the other hand, since neither u1 nor, u2 is a constant multiple of the other, the set of row vectors u1, u2 is linearly independent., Hence by Definition 8.3.1, rank(A) � 2., , See page 352 in Section 7.6., , Row Space In the terminology of the preceding chapter, the row vectors u1, u2, u3 of the, matrix (1) are a set of vectors in the vector space R4. Since RA � Span(u1, u2, u3) (the set of all, linear combinations of the vectors u1, u2, u3) is a subspace of R4, we are justified in calling RA, the row space of the matrix A. Now the set of vectors u1, u2 is linearly independent and also, spans RA; in other words, the set u1, u2 is a basis for RA. The dimension (the number of vectors, in a basis) of the row space RA is 2, which is rank(A)., Rank by Row Reduction Example 1 notwithstanding, it is generally not easy to, determine the rank of a matrix by inspection. Although there are several mechanical ways, of finding rank(A), we examine one way that uses the elementary row operations introduced, in the preceding section. Specifically, the rank of A can be found by row reducing A to a, row-echelon matrix B. To understand this, first recall that an m � n matrix B is row equivalent to an m � n matrix A if the rows of B were obtained from the rows of A by applying, elementary row operations. If we simply interchange two rows in A to obtain B, then the, row space RA of A and the row space RB of B are equal because the row vectors of A and B, are the same. When the row vectors of B are linear combinations of the rows of A, it follows, 8.3 Rank of a Matrix |, , 389

Page 159 :