Page 1 :

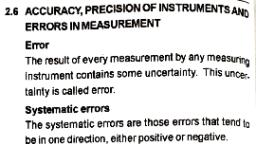

The quantities which can be measured by an instrument and by means of which we can describe, the laws of physics are called physical quantities., , QUANTI, , , , aa SUPPLEMENTRY, , , , antit Physical quantities which, hav t h can be expressed as a, rbitrar nd their unit combination of base, re for ( quantities are called derived, , pI | quantit quantities., h auantit ol . mye Length [m], ; P smoa e.g: Velocity} " “Time tel ts], , , , Magnitude of physical quantity = (numerical valt, , Magnitude of a physical quantity is always constant. It is independent of the type of unit., , Pa u,= constant, , ae, , ET a, , TLE

Page 2 :

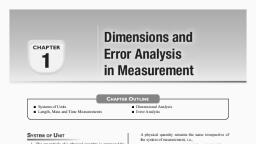

SSS, , , , Dimensions of a physical quantity are the power to which the fundamental !, quantities must be raised to represent the given physical quantity. !, , ee od See eet ore eee Set ee ete toto et, , , , , , , , n, fu] =n, [u,], , Suppose the dimensions of a physical quantity are ‘a’ in mass, 'b' in length and ‘c' in time. If the, fundamental units in one system are M,,L ‘ and T, and in the other system are M,,L,andT 3, respectively. Then we can write., , n, [Mi Lh TS] = n,[M5L3T;], , Every physical equation should be dimensionally balanced. This is called the ‘Principle of, Homogeneity’. The dimensions of each term on both sides of an equation must be the same., , Note: A dimensionally correct equation may or may not be physically correct, , , , , , , , , , , , , PRINCIPLE OF HOMOGENEITY OF DIMENSIONS, , This principle states that the dimensions of all the terms in a physical expression should be same., , : ; ‘ 1 ; ;, For e.g, in the physical expression s = ut + at”, the dimensions of s, ut and at’ all are same., 2, , Note: Physical quantities separated by the symbols +, -, =, >, < efc., have the same dimensions, , By this method, the value of dimensionless constant can not be calculated., , © By this method, the equation containing trigonometrical, exponential and logarithmic terms, cannot be analysed., , © If aphysical quantity depends on more than three factors, then relation among them cannot, be established because we can have only three equations by equating the powers of M, L, and T.

Page 3 :

Difference between the result of the measurement, and the true value of what you were measuring, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , RANDOM, , , , Random errors appear randomly because of the, operator, fluctuations in the external conditions, and variability of the measuring instruments. The, effect of random error can be some what reduced, by taking the average of measured values., Random errors have no fixed sign or size., , Thus they are represented in the form Ata, , , , Se wa le, , Systematic error occurs due to an error in the, procedure or miscalibration of the instrument etc., Such erors have same size and sign for all, measurements. Such errors can be determined., The systematic error is removed before beginning, calculations. Bench error and zero eror are, examples of systematic error., , ABSOLUTE, , Error may be expressed as absolute measures, giving the, size of the error in a quantity in the same units as the, quantity itself., , Least Count Error :- If the instrument has known least count,, , the absolute error is taken to be half of the least count unless, otherwise stated., , , , , , , , , , , , RELATIVE (OR FRACTIONAL), , , , Error may be expressed as relative measures, giving the, ratio of the quantity's error to the quantity itself, , , , , Absolute error in a measurement, Relative Error = —£@£@@————————_, Size of the measurement

Page 4 :

RULES OF RE) dS, , , , , , , , , , , , ADDITION & SUBTRACTION RULE, , , , The absolute random errors add, IfR=A+B,or R=A-B, thenr=a+b, , , , , , , POWER RULE, , When a quantity Q is raised to a power P,, the relative error in the result is P times the, WXZ relative error in Q. This also holds for, negative powers., , PRODUCT & QUOTIENT RULE, , , , , , The relative random errors add, Wa if = AB, or R=, then= 2242, B R A B, , , , , , IFR=@Q, then = =Px 2, , , , , , , , Q, Aad ti:, , Least count of Vernier Callipers, , The least count of Vernier Callipers (v.c) is the minimum value of correct, estimation of length without eye estimation. If N‘* division of vernier, , calliper coincides with (N-1) division of main scale, then, N(vs) =(N-1)ms => lvs= =, , vs = Vernier Scale Reading : ms=Main Scale Reading, , , , , , , , , , , , , , <}— Locking Screw, , (for measuring, Inner dimension), , Imperial Scale, , Metric Scale (ms), , , , , (for measuring, Outer dimension), , — Jaws, , Vernier, Scale (vs), , , , , , Vernier Constant = 1 ms -1 vs = [- a ms = =m. which is equal to the value of the, , smallest division on the main scale divided by total number of divisions on the vernier scale.

Page 5 :

@ The main scale or pitch scale is (M) graduated along the, axis of screw., , , , , , SSE, , RRS, , , , , , Ratchet Ratchar, , <j} Frame, , \ J, , , , , , Pitch :- The pitch of the instrument is distance between two consecutive threads of the, , screw which is equal to the distance moved by the screw due to one complete rotation, , of the cap. Thus for,, , 10 rotation of cap = 5 mm, then pitch = 0.5 mm., , Least count :- The minimum (or least) measurement (or count) of length is equal to one, , division on the head scale which is equal to pitch divided by the total cap divisions., Pitch, , Least SS, ee CONN Total cap divisions, , screw, Measurement of length by 6 Ney, , , , Length, L = n x pitch + f x least count,, where n = main scale reading & f = caps scale reading, , In a perfect instrument the zero of the main scale coincides, with the line of gradiation along the screw axis with no zero-error, otherwise the instrument, , is said to have zero-error which is equal to the cap reading with the gap closed. This error, is positive when zero line of reference line of the cap lies below the line of graduation and, vice-versa. The corresponding corrections will be just opposite.