Page 1 :

CHAPTER NINE, , MECHANICAL PROPERTIES, , 9.1, , 9.1, 9.2, 9.3, 9.4, 9.5, 9.6, 9.7, , Introduction, Elastic behaviour of solids, Stress and strain, Hooke’s law, Stress-strain curve, Elastic moduli, Applications of elastic, behaviour of materials, Summary, Points to ponder, Exercises, Additional exercises, , OF, , SOLIDS, , INTRODUCTION, , In Chapter 7, we studied the rotation of the bodies and then, realised that the motion of a body depends on how mass is, distributed within the body. We restricted ourselves to simpler, situations of rigid bodies. A rigid body generally means a, hard solid object having a definite shape and size. But in, reality, bodies can be stretched, compressed and bent. Even, the appreciably rigid steel bar can be deformed when a, sufficiently large external force is applied on it. This means, that solid bodies are not perfectly rigid., A solid has definite shape and size. In order to change (or, deform) the shape or size of a body, a force is required. If, you stretch a helical spring by gently pulling its ends, the, length of the spring increases slightly. When you leave the, ends of the spring, it regains its original size and shape. The, property of a body, by virtue of which it tends to regain its, original size and shape when the applied force is removed, is, known as elasticity and the deformation caused is known, as elastic deformation. However, if you apply force to a lump, of putty or mud, they have no gross tendency to regain their, previous shape, and they get permanently deformed. Such, substances are called plastic and this property is called, plasticity. Putty and mud are close to ideal plastics., The elastic behaviour of materials plays an important role, in engineering design. For example, while designing a, building, knowledge of elastic properties of materials like steel,, concrete etc. is essential. The same is true in the design of, bridges, automobiles, ropeways etc. One could also ask —, Can we design an aeroplane which is very light but, sufficiently strong? Can we design an artificial limb which, is lighter but stronger? Why does a railway track have a, particular shape like I? Why is glass brittle while brass is, not? Answers to such questions begin with the study of how, relatively simple kinds of loads or forces act to deform, different solids bodies. In this chapter, we shall study the, , 2019-20

Page 2 :

236, , PHYSICS, , elastic behaviour and mechanical properties of, solids which would answer many such, questions., 9.2 ELASTIC BEHAVIOUR OF SOLIDS, We know that in a solid, each atom or molecule, is surrounded by neighbouring atoms or, molecules. These are bonded together by, interatomic or intermolecular forces and stay, in a stable equilibrium position. When a solid is, deformed, the atoms or molecules are displaced, from their equilibrium positions causing a, change in the interatomic (or intermolecular), distances. When the deforming force is removed,, the interatomic forces tend to drive them back, to their original positions. Thus the body regains, its original shape and size. The restoring, mechanism can be visualised by taking a model, of spring-ball system shown in the Fig. 9.1. Here, the balls represent atoms and springs represent, interatomic forces., , Fig. 9.1 Spring-ball model for the illustration of elastic, behaviour of solids., , If you try to displace any ball from its, equilibrium position, the spring system tries to, restore the ball back to its original position. Thus, elastic behaviour of solids can be explained in, terms of microscopic nature of the solid. Robert, Hooke, an English physicist (1635 - 1703 A.D), performed experiments on springs and found, that the elongation (change in the length), produced in a body is proportional to the applied, force or load. In 1676, he presented his law of, , 2019-20, , elasticity, now called Hooke’s law. We shall, study about it in Section 9.4. This law, like, Boyle’s law, is one of the earliest quantitative, relationships in science. It is very important to, know the behaviour of the materials under, various kinds of load from the context of, engineering design., 9.3 STRESS AND STRAIN, When forces are applied on a body in such a, manner that the body is still in static equilibrium,, it is deformed to a small or large extent depending, upon the nature of the material of the body and, the magnitude of the deforming force. The, deformation may not be noticeable visually in, many materials but it is there. When a body is, subjected to a deforming force, a restoring force, is developed in the body. This restoring force is, equal in magnitude but opposite in direction to, the applied force. The restoring force per unit area, is known as stress. If F is the force applied normal, to the cross–section and A is the area of cross, section of the body,, Magnitude of the stress = F/A, (9.1), The SI unit of stress is N m–2 or pascal (Pa), and its dimensional formula is [ ML–1T–2 ]., There are three ways in which a solid may, change its dimensions when an external force, acts on it. These are shown in Fig. 9.2. In, Fig.9.2(a), a cylinder is stretched by two equal, forces applied normal to its cross-sectional area., The restoring force per unit area in this case, is called tensile stress. If the cylinder is, compressed under the action of applied forces,, the restoring force per unit area is known as, compressive stress. Tensile or compressive, stress can also be termed as longitudinal stress., In both the cases, there is a change in the, length of the cylinder. The change in the length, ∆L to the original length L of the body (cylinder, in this case) is known as longitudinal strain., Longitudinal strain =, , ∆L, L, , (9.2), , However, if two equal and opposite deforming, forces are applied parallel to the cross-sectional, area of the cylinder, as shown in Fig. 9.2(b),, there is relative displacement between the, opposite faces of the cylinder. The restoring force, per unit area developed due to the applied, tangential force is known as tangential or, shearing stress.

Page 3 :

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF SOLIDS, , 237, , Robert Hooke, (1635 – 1703 A.D.), Robert Hooke was born on July 18, 1635 in Freshwater, Isle of Wight. He was, one of the most brilliant and versatile seventeenth century English scientists., He attended Oxford University but never graduated. Yet he was an extremely, talented inventor, instrument-maker and building designer. He assisted Robert, Boyle in the construction of Boylean air pump. In 1662, he was appointed as, Curator of Experiments to the newly founded Royal Society. In 1665, he became, Professor of Geometry in Gresham College where he carried out his astronomical observations. He built a Gregorian reflecting telescope; discovered the fifth, star in the trapezium and an asterism in the constellation Orion; suggested that, Jupiter rotates on its axis; plotted detailed sketches of Mars which were later, used in the 19th century to determine the planet’s rate of rotation; stated the, inverse square law to describe planetary motion, which Newton modified later, etc. He was elected Fellow of Royal Society and also served as the Society’s, Secretary from 1667 to 1682. In his series of observations presented in Micrographia, he suggested, wave theory of light and first used the word ‘cell’ in a biological context as a result of his studies of cork., Robert Hooke is best known to physicists for his discovery of law of elasticity: Ut tensio, sic vis (This, is a Latin expression and it means as the distortion, so the force). This law laid the basis for studies of, stress and strain and for understanding the elastic materials., , As a result of applied tangential force, there, is a relative displacement ∆x between opposite, faces of the cylinder as shown in the Fig. 9.2(b)., The strain so produced is known as shearing, strain and it is defined as the ratio of relative, displacement of the faces ∆x to the length of, the cylinder L., Shearing strain =, , ∆x, = tan θ, L, , (9.3), , where θ is the angular displacement of the, cylinder from the vertical (original position of, the cylinder). Usually θ is very small, tan θ, is nearly equal to angle θ , (if θ = 10°, for, example, there is only 1% difference between θ, and tan θ)., , (a), Fig. 9.2, , It can also be visualised, when a book is, pressed with the hand and pushed horizontally,, as shown in Fig. 9.2 (c)., (9.4), Thus, shearing strain = tan θ ≈ θ, In Fig. 9.2 (d), a solid sphere placed in the, fluid under high pressure is compressed, uniformly on all sides. The force applied by the, fluid acts in perpendicular direction at each, point of the surface and the body is said to be, under hydraulic compression. This leads to, decrease in its volume without any change of, its geometrical shape., The body develops internal restoring forces, that are equal and opposite to the forces applied, by the fluid (the body restores its original shape, and size when taken out from the fluid). The, internal restoring force per unit area in this case, , (b), , (c), , (d), , (a) A cylindrical body under tensile stress elongates by ∆L (b) Shearing stress on a cylinder deforming it by, an angle θ (c) A body subjected to shearing stress (d) A solid body under a stress normal to the surface at, every point (hydraulic stress). The volumetric strain is ∆V/V, but there is no change in shape., , 2019-20

Page 4 :

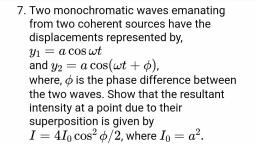

238, , PHYSICS, , is known as hydraulic stress and in magnitude, is equal to the hydraulic pressure (applied force, per unit area)., The strain produced by a hydraulic pressure, is called volume strain and is defined as the, ratio of change in volume (∆V) to the original, volume (V )., Volume strain =, , ∆V, V, , The body regains its original dimensions when, the applied force is removed. In this region, the, solid behaves as an elastic body., , (9.5), , Since the strain is a ratio of change in, dimension to the original dimension, it has no, units or dimensional formula., 9.4 HOOKE’S LAW, Stress and strain take different forms in the, situations depicted in the Fig. (9.2). For small, deformations the stress and strain are, proportional to each other. This is known as, Hooke’s law., Thus,, stress ∝ strain, stress = k × strain, (9.6), where k is the proportionality constant and is, known as modulus of elasticity., Hooke’s law is an empirical law and is found, to be valid for most materials. However, there, are some materials which do not exhibit this, linear relationship., 9.5 STRESS-STRAIN CURVE, The relation between the stress and the strain, for a given material under tensile stress can be, found experimentally. In a standard test of, tensile properties, a test cylinder or a wire is, stretched by an applied force. The fractional, change in length (the strain) and the applied, force needed to cause the strain are recorded., The applied force is gradually increased in steps, and the change in length is noted. A graph is, plotted between the stress (which is equal in, magnitude to the applied force per unit area), and the strain produced. A typical graph for a, metal is shown in Fig. 9.3. Analogous graphs, for compression and shear stress may also be, obtained. The stress-strain curves vary from, material to material. These curves help us to, understand how a given material deforms with, increasing loads. From the graph, we can see, that in the region between O to A, the curve is, linear. In this region, Hooke’s law is obeyed., , 2019-20, , Fig. 9.3 A typical stress-strain curve for a metal., , In the region from A to B, stress and strain, are not proportional. Nevertheless, the body still, returns to its original dimension when the load, is removed. The point B in the curve is known, as yield point (also known as elastic limit) and, the corresponding stress is known as yield, strength (σy ) of the material., If the load is increased further, the stress, developed exceeds the yield strength and strain, increases rapidly even for a small change in the, stress. The portion of the curve between B and, D shows this. When the load is removed, say at, some point C between B and D, the body does, not regain its original dimension. In this case,, even when the stress is zero, the strain is not, zero. The material is said to have a permanent, set. The deformation is said to be plastic, deformation. The point D on the graph is the, ultimate tensile strength (σu ) of the material., Beyond this point, additional strain is produced, even by a reduced applied force and fracture, occurs at point E. If the ultimate strength and, fracture points D and E are close, the material, is said to be brittle. If they are far apart, the, material is said to be ductile., As stated earlier, the stress-strain behaviour, varies from material to material. For example,, rubber can be pulled to several times its original, length and still returns to its original shape., Fig. 9.4 shows stress-strain curve for the elastic, tissue of aorta, present in the heart. Note that, although elastic region is very large, the material

Page 5 :

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF SOLIDS, , 239, , 9.6.1 Young’s Modulus, Experimental observation show that for a given, material, the magnitude of the strain produced, is same whether the stress is tensile or, compressive. The ratio of tensile (or compressive), stress (σ ) to the longitudinal strain (ε) is defined as, Young’s modulus and is denoted by the symbol Y., Y=, , σ, ε, , (9.7), , From Eqs. (9.1) and (9.2), we have, , Fig. 9.4, , Stress-strain curve for the elastic tissue of, Aorta, the large tube (vessel) carrying blood, from the heart., , does not obey Hooke’s law over most of the, region. Secondly, there is no well defined plastic, region. Substances like tissue of aorta, rubber, etc. which can be stretched to cause large strains, are called elastomers., 9.6 ELASTIC MODULI, The proportional region within the elastic limit, of the stress-strain curve (region OA in Fig. 9.3), is of great importance for structural and, manufacturing engineering designs. The ratio, of stress and strain, called modulus of elasticity,, is found to be a characteristic of the material., , Y = (F/A)/(∆L/L), = (F × L) /(A × ∆L), (9.8), Since strain is a dimensionless quantity, the, unit of Young’s modulus is the same as that of, stress i.e., N m–2 or Pascal (Pa). Table 9.1 gives, the values of Young’s moduli and yield strengths, of some material., From the data given in Table 9.1, it is noticed, that for metals Young’s moduli are large., Therefore, these materials require a large force, to produce small change in length. To increase, the length of a thin steel wire of 0.1 cm2 crosssectional area by 0.1%, a force of 2000 N is, required. The force required to produce the same, strain in aluminium, brass and copper wires, having the same cross-sectional area are 690 N,, 900 N and 1100 N respectively. It means that, steel is more elastic than copper, brass and, aluminium. It is for this reason that steel is, , Table 9.1 Young’s moduli and yield strenghs of some material, , # Substance tested under compression, , 2019-20

Page 6 :

240, , PHYSICS, , preferred in heavy-duty machines and in, structural designs. Wood, bone, concrete and, glass have rather small Young’s moduli., u Example 9.1 A structural steel rod has a, radius of 10 mm and a length of 1.0 m. A, 100 kN force stretches it along its length., Calculate (a) stress, (b) elongation, and (c), strain on the rod. Young’s modulus, of, structural steel is 2.0 × 1011 N m-2., Answer We assume that the rod is held by a, clamp at one end, and the force F is applied at, the other end, parallel to the length of the rod., Then the stress on the rod is given by, Stress =, , F, A, , F, , =, , πr, , u Example 9.3 In a human pyramid in a, circus, the entire weight of the balanced, group is supported by the legs of a, performer who is lying on his back (as, shown in Fig. 9.5). The combined mass of, all the persons performing the act, and the, tables, plaques etc. involved is 280 kg. The, mass of the performer lying on his back at, the bottom of the pyramid is 60 kg. Each, thighbone (femur) of this performer has a, length of 50 cm and an effective radius of, 2.0 cm. Determine the amount by which, each thighbone gets compressed under the, extra load., , 2, 3, , 100 × 10 N, , =, , (, , 3.14 × 10, , −2, , m, , 2, , ), , = 3.18 × 108 N m–2, The elongation,, ∆L =, , =, , ( F/A ) L, Y, , (3.18 × 10, , 8, , N m, , 11, , –2, , where the subscripts c and s refer to copper, and stainless steel respectively. Or,, ∆Lc/∆Ls = (Ys/Yc) × (Lc/Ls), Given Lc = 2.2 m, Ls = 1.6 m,, From Table 9.1 Yc = 1.1 × 1011 N.m–2, and, Ys = 2.0 × 1011 N.m–2., 11, ∆Lc/∆Ls = (2.0 × 10 /1.1 × 1011) × (2.2/1.6) = 2.5., The total elongation is given to be, ∆Lc + ∆Ls = 7.0 × 10-4 m, Solving the above equations,, ∆Lc = 5.0 × 10-4 m, and ∆Ls = 2.0 × 10-4 m., Therefore, W = (A × Yc × ∆Lc)/Lc, = π (1.5 × 10-3)2 × [(5.0 × 10-4 × 1.1 × 1011)/2.2], = 1.8 × 102 N, t, , ) (1m ), , –2, , 2 × 10 N m, = 1.59 × 10–3 m, = 1.59 mm, The strain is given by, Strain = ∆L/L, = (1.59 × 10–3 m)/(1m), = 1.59 × 10–3, = 0.16 %, , t, , u Example 9.2 A copper wire of length 2.2, m and a steel wire of length 1.6 m, both of, diameter 3.0 mm, are connected end to end., When stretched by a load, the net, elongation is found to be 0.70 mm. Obtain, the load applied., Answer The copper and steel wires are under, a tensile stress because they have the same, tension (equal to the load W) and the same area, of cross-section A. From Eq. (9.7) we have stress, = strain × Young’s modulus. Therefore, W/A = Yc × (∆Lc/Lc) = Ys × (∆Ls/Ls), , 2019-20, , Fig. 9.5 Human pyramid in a circus.

Page 7 :

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF SOLIDS, , Answer Total mass of all the performers, tables,, plaques etc., = 280 kg, Mass of the performer = 60 kg, Mass supported by the legs of the performer, at the bottom of the pyramid, = 280 – 60 = 220 kg, Weight of this supported mass, = 220 kg wt. = 220 × 9.8 N = 2156 N., Weight supported by each thighbone of the, performer = ½ (2156) N = 1078 N., From Table 9.1, the Young’s modulus for bone, is given by, Y, = 9.4 × 109 N m–2., Length of each thighbone L = 0.5 m, the radius of thighbone = 2.0 cm, Thus the cross-sectional area of the thighbone, A = π × (2 × 10-2)2 m2 = 1.26 × 10-3 m2., Using Eq. (9.8), the compression in each, thighbone (∆L) can be computed as, ∆L, = [(F × L)/(Y × A)], = [(1078 × 0.5)/(9.4 × 109 × 1.26 × 10-3)], = 4.55 × 10-5 m or 4.55 × 10-3 cm., This is a very small change! The fractional, decrease in the thighbone is ∆L/L = 0.000091, or 0.0091%., t, 9.6.2 Determination of Young’s Modulus of, the Material of a Wire, A typical experimental arrangement to determine, the Young’s modulus of a material of wire under, tension is shown in Fig. 9.6. It consists of two, long straight wires of same length and equal, radius suspended side by side from a fixed rigid, support. The wire A (called the reference wire), carries a millimetre main scale M and a pan to, place a weight. The wire B (called the, experimental wire) of uniform area of crosssection also carries a pan in which known, weights can be placed. A vernier scale V is, attached to a pointer at the bottom of the, experimental wire B, and the main scale M is, fixed to the reference wire A. The weights placed, in the pan exert a downward force and stretch, the experimental wire under a tensile stress. The, elongation of the wire (increase in length) is, measured by the vernier arrangement. The, reference wire is used to compensate for any, change in length that may occur due to change, in room temperature, since any change in length, of the reference wire due to temperature change, , 241, , will be accompanied by an equal change in, experimental wire. (We shall study these, temperature effects in detail in Chapter 11.), , Fig. 9.6, , An arrangement for the determination of, Young’s modulus of the material of a wire., , Both the reference and experimental wires are, given an initial small load to keep the wires, straight and the vernier reading is noted. Now, the experimental wire is gradually loaded with, more weights to bring it under a tensile stress, and the vernier reading is noted again. The, difference between two vernier readings gives, the elongation produced in the wire. Let r and L, be the initial radius and length of the, experimental wire, respectively. Then the area, of cross-section of the wire would be πr2. Let M, be the mass that produced an elongation ∆L in, the wire. Thus the applied force is equal to Mg,, where g is the acceleration due to gravity. From, Eq. (9.8), the Young’s modulus of the material, of the experimental wire is given by, , Y=, , Mg L, σ, = π r 2 . ∆L, ε, , = Mg × L/(πr2 × ∆L), , 2019-20, , (9.9)

Page 8 :

242, , PHYSICS, , 9.6.3 Shear Modulus, The ratio of shearing stress to the corresponding, shearing strain is called the shear modulus of, the material and is represented by G. It is also, called the modulus of rigidity., G = shearing stress (σs)/shearing strain, G = (F/A)/(∆x/L), = (F × L)/(A × ∆x), (9.10), Similarly, from Eq. (9.4), G = (F/A)/θ, = F/(A × θ), (9.11), The shearing stress σs can also be expressed as, σs = G × θ, (9.12), SI unit of shear modulus is N m–2 or Pa. The, shear moduli of a few common materials are, given in Table 9.2. It can be seen that shear, modulus (or modulus of rigidity) is generally less, than Young’s modulus (from Table 9.1). For most, materials G ≈ Y/3., Table 9.2, , Shear moduli (G) of some common, materials, , Material, Aluminium, Brass, Copper, Glass, Iron, Lead, Nickel, Steel, Tungsten, Wood, , 9, , G (10 Nm, or GPa), , –2, , 25, 36, 42, 23, 70, 5.6, 77, 84, 150, 10, , u Example 9.4 A square lead slab of side 50, cm and thickness 10 cm is subject to a, shearing force (on its narrow face) of 9.0 ×, 104 N. The lower edge is riveted to the floor., How much will the upper edge be displaced?, Answer The lead slab is fixed and the force is, applied parallel to the narrow face as shown in, Fig. 9.7. The area of the face parallel to which, this force is applied is, A = 50 cm × 10 cm, = 0.5 m × 0.1 m, = 0.05 m2, , 2019-20, , Therefore, the stress applied is, = (9.4 × 104 N/0.05 m2), = 1.80 × 106 N.m–2, , aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa, aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa, Fig. 9.7, , We know that shearing strain = (∆x/L)= Stress /G., Therefore the displacement ∆x = (Stress × L)/G, = (1.8 × 106 N m–2 × 0.5m)/(5.6 × 109 N m–2), = 1.6 × 10–4 m = 0.16 mm, t, 9.6.4 Bulk Modulus, In Section (9.3), we have seen that when a body, is submerged in a fluid, it undergoes a hydraulic, stress (equal in magnitude to the hydraulic, pressure). This leads to the decrease in the, volume of the body thus producing a strain called, volume strain [Eq. (9.5)]. The ratio of hydraulic, stress to the corresponding hydraulic strain is, called bulk modulus. It is denoted by symbol B., B = – p/(∆V/V), (9.13), The negative sign indicates the fact that with, an increase in pressure, a decrease in volume, occurs. That is, if p is positive, ∆V is negative., Thus for a system in equilibrium, the value of, bulk modulus B is always positive. SI unit of, bulk modulus is the same as that of pressure, i.e., N m–2 or Pa. The bulk moduli of a few, common materials are given in Table 9.3., The reciprocal of the bulk modulus is called, compressibility and is denoted by k. It is defined, as the fractional change in volume per unit, increase in pressure., k = (1/B) = – (1/∆p) × (∆V/V), (9.14), It can be seen from the data given in Table, 9.3 that the bulk moduli for solids are much, larger than for liquids, which are again much, larger than the bulk modulus for gases (air).

Page 9 :

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF SOLIDS, , Table 9.3, , Bulk moduli (B) of some common, Materials, , B (109 N m–2 or GPa), , Material, Solids, Aluminium, , 72, , Brass, Copper, , 61, 140, , Glass, Iron, , 37, 100, , Nickel, Steel, , 260, 160, , Liquids, Water, , 2.2, , Ethanol, Carbon disulphide, , 0.9, 1.56, , Glycerine, Mercury, , 4.76, 25, , Gases, Air (at STP), , 1.0 × 10–4, , Thus, solids are the least compressible, whereas,, gases are the most compressible. Gases are about, a million times more compressible than solids!, , 243, , Gases have large compressibilities, which vary, with pressure and temperature. The, incompressibility of the solids is primarily due, to the tight coupling between the neighbouring, atoms. The molecules in liquids are also bound, with their neighbours but not as strong as in, solids. Molecules in gases are very poorly, coupled to their neighbours., Table 9.4 shows the various types of stress,, strain, elastic moduli, and the applicable state, of matter at a glance., u Example 9.5 The average depth of Indian, Ocean is about 3000 m. Calculate the, fractional compression, ∆V/V, of water at, the bottom of the ocean, given that the bulk, modulus of water is 2.2 × 109 N m–2. (Take, g = 10 m s–2), Answer The pressure exerted by a 3000 m, column of water on the bottom layer, p = hρ g = 3000 m × 1000 kg m–3 × 10 m s–2, = 3 × 107 kg m–1 s-2, = 3 × 107 N m–2, Fractional compression ∆V/V, is, ∆V/V = stress/B = (3 × 107 N m-2)/(2.2 × 109 N m–2), = 1.36 × 10-2 or 1.36 %, t, , Table 9.4 Stress, strain and various elastic moduli, Type of, stress, , Stress, , Strain, , Change in, shape volume, , Elastic, Modulus, , Name of, Modulus, , State of, Matter, , Tensile, or, compressive, (σ = F/A), , Two equal and, opposite forces, perpendicular to, opposite faces, , Elongation or, compression, parallel to force, direction (∆L/L), (longitudinal strain), , Yes, , No, , Y = (F×L)/, (A×∆L), , Young’s, modulus, , Solid, , Shearing, (σs = F/A), , Two equal and, opposite forces, parallel to oppoiste, surfaces forces, in each case such, that total force and, total torque on the, body vanishes, , Pure shear, θ, , Yes, , No, , G = F/(A×θ), , Hydraulic, , Forces perpendicular, everywhere to the, surface, force per, unit area (pressure), same everywhere., , Volume change, (compression or, elongation), (∆V/V), , No, , Yes, , 2019-20, , Shear, Solid, modulus, or modulus, of rigidity, , B = –p/(∆V/V) Bulk, modulus, , Solid, liquid, and gas

Page 10 :

244, , PHYSICS, , 9.6.5 POISSON’S RATIO, Careful observations with the Young’s modulus, experiment (explained in section 9.6.2), show, that there is also a slight reduction in the crosssection (or in the diameter) of the wire. The strain, perpendicular to the applied force is called, lateral strain. Simon Poisson pointed out that, within the elastic limit, lateral strain is directly, proportional to the longitudinal strain. The ratio, of the lateral strain to the longitudinal strain in, a stretched wire is called Poisson’s ratio. If the, original diameter of the wire is d and the, contraction of the diameter under stress is ∆d,, the lateral strain is ∆d/d. If the original length, of the wire is L and the elongation under stress, is ∆L, the longitudinal strain is ∆L/L. Poisson’s, ratio is then (∆d/d)/(∆L/L) or (∆d/∆L) × (L/d)., Poisson’s ratio is a ratio of two strains; it is a, pure number and has no dimensions or units., Its value depends only on the nature of material., For steels the value is between 0.28 and 0.30,, and for aluminium alloys it is about 0.33., 9.6.6 Elastic Potential Energy, in a Stretched Wire, When a wire is put under a tensile stress, work, is done against the inter-atomic forces. This, work is stored in the wire in the form of elastic, potential energy. When a wire of original length, L and area of cross-section A is subjected to a, deforming force F along the length of the wire,, let the length of the wire be elongated by l. Then, from Eq. (9.8), we have F = YA × (l/L). Here Y is, the Young’s modulus of the material of the wire., Now for a further elongation of infinitesimal, small length dl, work done dW is F × dl or YAldl/, L. Therefore, the amount of work done (W) in, increasing the length of the wire from L to L + l,, that is from l = 0 to l = l is, W=, , l, , ∫0, , YAl, YA l 2, dl =, ×, L, 2, L, 2, , 1, l , W = × Y × × AL, 2, L , =, , 1, × Young’s modulus × strain2 ×, 2, volume of the wire, , 2019-20, , 1, × stress × strain × volume of the, 2, wire, This work is stored in the wire in the form of, elastic potential energy (U). Therefore the elastic, potential energy per unit volume of the wire (u) is, =, , u=, 9.7, , 1, ×σε, 2, , (9.15), , APPLICATIONS OF ELASTIC, BEHAVIOUR OF MATERIALS, , The elastic behaviour of materials plays an, important role in everyday life. All engineering, designs require precise knowledge of the elastic, behaviour of materials. For example while, designing a building, the structural design of, the columns, beams and supports require, knowledge of strength of materials used. Have, you ever thought why the beams used in, construction of bridges, as supports etc. have, a cross-section of the type I? Why does a heap, of sand or a hill have a pyramidal shape?, Answers to these questions can be obtained, from the study of structural engineering which, is based on concepts developed here., Cranes used for lifting and moving heavy, loads from one place to another have a thick, metal rope to which the load is attached. The, rope is pulled up using pulleys and motors., Suppose we want to make a crane, which has, a lifting capacity of 10 tonnes or metric tons (1, metric ton = 1000 kg). How thick should the, steel rope be? We obviously want that the load, does not deform the rope permanently., Therefore, the extension should not exceed the, elastic limit. From Table 9.1, we find that mild, steel has a yield strength (σy) of about 300 ×, 106 N m–2. Thus, the area of cross-section (A), of the rope should at least be, A ≥ W/σy = Mg/σy, (9.16), = (104 kg × 9.8 m s-2)/(300 × 106 N m-2), = 3.3 × 10-4 m2, corresponding to a radius of about 1 cm for, a rope of circular cross-section. Generally, a large margin of safety (of about a factor of, ten in the load) is provided. Thus a thicker, rope of radius about 3 cm is recommended., A single wire of this radius would practically, be a rigid rod. So the ropes are always made, of a number of thin wires braided together,

Page 11 :

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF SOLIDS, , 245, , like in pigtails, for ease in manufacture,, flexibility and strength., A bridge has to be designed such that it can, withstand the load of the flowing traffic, the force, of winds and its own weight. Similarly, in the, design of buildings the use of beams and columns, is very common. In both the cases, the, overcoming of the problem of bending of beam, under a load is of prime importance. The beam, should not bend too much or break. Let us, consider the case of a beam loaded at the centre, and supported near its ends as shown in, Fig. 9.8. A bar of length l, breadth b, and depth d, when loaded at the centre by a load W sags by, an amount given by, , δ = W l 3/(4bd 3Y), , Fig. 9.8, , (9.17), , (a), Fig. 9.9, , (b), , (c), , Different cross-sectional shapes of a beam., (a) Rectangular section of a bar;, (b) A thin bar and how it can buckle;, (c) Commonly used section for a load, bearing bar., , The use of pillars or columns is also very, common in buildings and bridges. A pillar with, rounded ends as shown in Fig. 9.10(a) supports, less load than that with a distributed shape at, the ends [Fig. 9.10(b)]. The precise design of a, bridge or a building has to take into account, the conditions under which it will function, the, cost and long period, reliability of usable, material, etc., , A beam supported at the ends and loaded, at the centre., , This relation can be derived using what you, have already learnt and a little calculus. From, Eq. (9.16), we see that to reduce the bending, for a given load, one should use a material with, a large Young’s modulus Y. For a given material,, increasing the depth d rather than the breadth, b is more effective in reducing the bending, since, δ is proportional to d -3 and only to b-1(of course, the length l of the span should be as small as, possible). But on increasing the depth, unless, the load is exactly at the right place (difficult to, arrange in a bridge with moving traffic), the, deep bar may bend as shown in Fig. 9.9(b). This, is called buckling. To avoid this, a common, compromise is the cross-sectional shape shown, in Fig. 9.9(c). This section provides a large loadbearing surface and enough depth to prevent, bending. This shape reduces the weight of the, beam without sacrificing the strength and, hence reduces the cost., , (a), Fig. 9.10, , (b), , Pillars or columns: (a) a pillar with rounded, ends, (b) Pillar with distributed ends., , The answer to the question why the maximum, height of a mountain on earth is ~10 km can, also be provided by considering the elastic, properties of rocks. A mountain base is not under, uniform compression and this provides some, shearing stress to the rocks under which they, can flow. The stress due to all the material on, the top should be less than the critical shearing, stress at which the rocks flow., At the bottom of a mountain of height h, the, force per unit area due to the weight of the, mountain is hρg where ρ is the density of the, material of the mountain and g is the acceleration, , 2019-20

Page 12 :

246, , PHYSICS, , due to gravity. The material at the bottom, experiences this force in the vertical direction,, and the sides of the mountain are free. Therefore,, this is not a case of pressure or bulk compression., There is a shear component, approximately hρg, itself. Now the elastic limit for a typical rock is, , 30 × 107 N m-2. Equating this to hρg, with, ρ = 3 × 103 kg m-3 gives, hρg = 30 × 107 N m-2 ., h, = 30 × 107 N m-2/(3 × 103 kg m-3 × 10 m s-2), = 10 km, which is more than the height of Mt. Everest!, , SUMMARY, 1., , 2., , 3., , 4., , 5., , Stress is the restoring force per unit area and strain is the fractional change in dimension., In general there are three types of stresses (a) tensile stress — longitudinal stress, (associated with stretching) or compressive stress (associated with compression),, (b) shearing stress, and (c) hydraulic stress., For small deformations, stress is directly proportional to the strain for many materials., This is known as Hooke’s law. The constant of proportionality is called modulus of, elasticity. Three elastic moduli viz., Young’s modulus, shear modulus and bulk modulus, are used to describe the elastic behaviour of objects as they respond to deforming forces, that act on them., A class of solids called elastomers does not obey Hooke’s law., When an object is under tension or compression, the Hooke’s law takes the form, F/A = Y∆L/L, where ∆L/L is the tensile or compressive strain of the object, F is the magnitude of the, applied force causing the strain, A is the cross-sectional area over which F is applied, (perpendicular to A) and Y is the Young’s modulus for the object. The stress is F/A., A pair of forces when applied parallel to the upper and lower faces, the solid deforms so, that the upper face moves sideways with respect to the lower. The horizontal displacement, ∆L of the upper face is perpendicular to the vertical height L. This type of deformation is, called shear and the corresponding stress is the shearing stress. This type of stress is, possible only in solids., In this kind of deformation the Hooke’s law takes the form, F/A = G × ∆L/L, where ∆L is the displacement of one end of object in the direction of the applied force F,, and G is the shear modulus., When an object undergoes hydraulic compression due to a stress exerted by a surrounding, fluid, the Hooke’s law takes the form, p = B (∆V/V),, where p is the pressure (hydraulic stress) on the object due to the fluid, ∆V/V (the, volume strain) is the absolute fractional change in the object’s volume due to that, pressure and B is the bulk modulus of the object., , POINTS TO PONDER, 1., , In the case of a wire, suspended from celing and stretched under the action of a weight (F), suspended from its other end, the force exerted by the ceiling on it is equal and opposite, to the weight. However, the tension at any cross-section A of the wire is just F and not, 2F. Hence, tensile stress which is equal to the tension per unit area is equal to F/A., , 2., , Hooke’s law is valid only in the linear part of stress-strain curve., , 3., , The Young’s modulus and shear modulus are relevant only for solids since only solids, have lengths and shapes., , 4., , Bulk modulus is relevant for solids, liquid and gases. It refers to the change in volume, when every part of the body is under the uniform stress so that the shape of the body, remains unchanged., , 2019-20

Page 13 :

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF SOLIDS, , 247, , 5., , Metals have larger values of Young’s modulus than alloys and elastomers. A material, with large value of Young’s modulus requires a large force to produce small changes in, its length., , 6., , In daily life, we feel that a material which stretches more is more elastic, but it a is, misnomer. In fact material which stretches to a lesser extent for a given load is considered, to be more elastic., , 7., , In general, a deforming force in one direction can produce strains in other directions, also. The proportionality between stress and strain in such situations cannot be described, by just one elastic constant. For example, for a wire under longitudinal strain, the, lateral dimensions (radius of cross section) will undergo a small change, which is described, by another elastic constant of the material (called Poisson ratio)., , 8., , Stress is not a vector quantity since, unlike a force, the stress cannot be assigned a, specific direction. Force acting on the portion of a body on a specified side of a section, has a definite direction., EXERCISES, , 9.1, , A steel wire of length 4.7 m and cross-sectional area 3.0 × 10-5 m2 stretches by the same, amount as a copper wire of length 3.5 m and cross-sectional area of 4.0 × 10–5 m2 under, a given load. What is the ratio of the Young’s modulus of steel to that of copper?, , 9.2, , Figure 9.11 shows the strain-stress curve for a given material. What are (a) Young’s, modulus and (b) approximate yield strength for this material?, , 9.3, , Fig. 9.11, The stress-strain graphs for materials A and B are shown in Fig. 9.12., , Fig. 9.12, , 2019-20

Page 14 :

248, , PHYSICS, , The graphs are drawn to the same scale., (a) Which of the materials has the greater Young’s modulus?, (b) Which of the two is the stronger material?, 9.4, , Read the following two statements below carefully and state, with reasons, if it is true, or false., (a) The Young’s modulus of rubber is greater than that of steel;, (b) The stretching of a coil is determined by its shear modulus., , 9.5 Two wires of diameter 0.25 cm, one made of steel and the other made of brass are, loaded as shown in Fig. 9.13. The unloaded length of steel wire is 1.5 m and that of, brass wire is 1.0 m. Compute the elongations of the steel and the brass wires., , 9.6, , 9.7, , 9.8, , 9.9, 9.10, , 9.11, , 9.12, , 9.13, 9.14, 9.15, 9.16, , Fig. 9.13, The edge of an aluminium cube is 10 cm long. One face of the cube is firmly fixed to a, vertical wall. A mass of 100 kg is then attached to the opposite face of the cube. The, shear modulus of aluminium is 25 GPa. What is the vertical deflection of this face?, Four identical hollow cylindrical columns of mild steel support a big structure of mass, 50,000 kg. The inner and outer radii of each column are 30 and 60 cm respectively., Assuming the load distribution to be uniform, calculate the compressional strain of, each column., A piece of copper having a rectangular cross-section of 15.2 mm × 19.1 mm is pulled in, tension with 44,500 N force, producing only elastic deformation. Calculate the resulting, strain?, A steel cable with a radius of 1.5 cm supports a chairlift at a ski area. If the maximum, stress is not to exceed 108 N m–2, what is the maximum load the cable can support ?, A rigid bar of mass 15 kg is supported symmetrically by three wires each 2.0 m long., Those at each end are of copper and the middle one is of iron. Determine the ratios of, their diameters if each is to have the same tension., A 14.5 kg mass, fastened to the end of a steel wire of unstretched length 1.0 m, is, whirled in a vertical circle with an angular velocity of 2 rev/s at the bottom of the circle., The cross-sectional area of the wire is 0.065 cm2. Calculate the elongation of the wire, when the mass is at the lowest point of its path., Compute the bulk modulus of water from the following data: Initial volume = 100.0, litre, Pressure increase = 100.0 atm (1 atm = 1.013 × 105 Pa), Final volume = 100.5, litre. Compare the bulk modulus of water with that of air (at constant temperature)., Explain in simple terms why the ratio is so large., What is the density of water at a depth where pressure is 80.0 atm, given that its, density at the surface is 1.03 × 103 kg m–3?, Compute the fractional change in volume of a glass slab, when subjected to a hydraulic, pressure of 10 atm., Determine the volume contraction of a solid copper cube, 10 cm on an edge, when, subjected to a hydraulic pressure of 7.0 × 106 Pa., How much should the pressure on a litre of water be changed to compress it by 0.10%?, , 2019-20

Page 15 :

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF SOLIDS, , 249, , Additional Exercises, 9.17 Anvils made of single crystals of diamond, with the shape as shown in, Fig. 9.14, are used to investigate behaviour of materials under very high pressures. Flat, faces at the narrow end of the anvil have a diameter of 0.50 mm, and the wide ends are, subjected to a compressional force of 50,000 N. What is the pressure at the tip of the anvil?, , Fig. 9.14, 9.18 A rod of length 1.05 m having negligible mass is supported at its ends by two wires of, steel (wire A) and aluminium (wire B) of equal lengths as shown in, Fig. 9.15. The cross-sectional areas of wires A and B are 1.0 mm2 and 2.0 mm2,, respectively. At what point along the rod should a mass m be suspended in order to, produce (a) equal stresses and (b) equal strains in both steel and aluminium wires., , Fig. 9.15, 9.19 A mild steel wire of length 1.0 m and cross-sectional area 0.50 × 10-2 cm2 is, stretched, well within its elastic limit, horizontally between two pillars. A mass of 100, g is suspended from the mid-point of the wire. Calculate the depression at the midpoint., 9.20 Two strips of metal are riveted together at their ends by four rivets, each of diameter 6.0, mm. What is the maximum tension that can be exerted by the riveted strip if the, shearing stress on the rivet is not to exceed 6.9 × 107 Pa? Assume that each rivet is to, carry one quarter of the load., 9.21 The Marina trench is located in the Pacific Ocean, and at one place it is nearly eleven, km beneath the surface of water. The water pressure at the bottom of the trench is, about 1.1 × 108 Pa. A steel ball of initial volume 0.32 m3 is dropped into the ocean and, falls to the bottom of the trench. What is the change in the volume of the ball when it, reaches to the bottom?, , 2019-20

Page 16 :

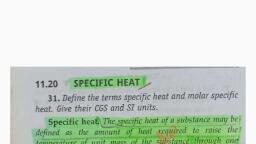

CHAPTER TEN, , MECHANICAL PROPERTIES, , OF, , FLUIDS, , 10.1 INTRODUCTION, , 10.1, 10.2, 10.3, 10.4, 10.5, 10.6, , Introduction, Pressure, Streamline flow, Bernoulli’s principle, Viscosity, Surface tension, Summary, Points to ponder, Exercises, Additional exercises, Appendix, , In this chapter, we shall study some common physical, properties of liquids and gases. Liquids and gases can flow, and are therefore, called fluids. It is this property that, distinguishes liquids and gases from solids in a basic way., Fluids are everywhere around us. Earth has an envelop of, air and two-thirds of its surface is covered with water. Water, is not only necessary for our existence; every mammalian, body constitute mostly of water. All the processes occurring, in living beings including plants are mediated by fluids. Thus, understanding the behaviour and properties of fluids is, important., How are fluids different from solids? What is common in, liquids and gases? Unlike a solid, a fluid has no definite, shape of its own. Solids and liquids have a fixed volume,, whereas a gas fills the entire volume of its container. We, have learnt in the previous chapter that the volume of solids, can be changed by stress. The volume of solid, liquid or gas, depends on the stress or pressure acting on it. When we, talk about fixed volume of solid or liquid, we mean its volume, under atmospheric pressure. The difference between gases, and solids or liquids is that for solids or liquids the change, in volume due to change of external pressure is rather small., In other words solids and liquids have much lower, compressibility as compared to gases., Shear stress can change the shape of a solid keeping its, volume fixed. The key property of fluids is that they offer, very little resistance to shear stress; their shape changes by, application of very small shear stress. The shearing stress, of fluids is about million times smaller than that of solids., 10.2 PRESSURE, A sharp needle when pressed against our skin pierces it. Our, skin, however, remains intact when a blunt object with a, wider contact area (say the back of a spoon) is pressed against, it with the same force. If an elephant were to step on a man’s, chest, his ribs would crack. A circus performer across whose, , 2019-20

Page 17 :

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF FLUIDS, , 251, , chest a large, light but strong wooden plank is, placed first, is saved from this accident. Such, everyday experiences convince us that both the, force and its coverage area are important. Smaller, the area on which the force acts, greater is the, impact. This impact is known as pressure., When an object is submerged in a fluid at, rest, the fluid exerts a force on its surface. This, force is always normal to the object’s surface., This is so because if there were a component of, force parallel to the surface, the object will also, exert a force on the fluid parallel to it; as a, consequence of Newton’s third law. This force, will cause the fluid to flow parallel to the surface., Since the fluid is at rest, this cannot happen., Hence, the force exerted by the fluid at rest has, to be perpendicular to the surface in contact, with it. This is shown in Fig.10.1(a)., The normal force exerted by the fluid at a point, may be measured. An idealised form of one such, pressure-measuring device is shown in Fig., 10.1(b). It consists of an evacuated chamber with, a spring that is calibrated to measure the force, acting on the piston. This device is placed at a, point inside the fluid. The inward force exerted, by the fluid on the piston is balanced by the, outward spring force and is thereby measured., , (a), (b), Fig. 10.1 (a) The force exerted by the liquid in the, beaker on the submerged object or on the, walls is normal (perpendicular) to the, surface at all points., (b) An idealised device for measuring, pressure., , In principle, the piston area can be made, arbitrarily small. The pressure is then defined, in a limiting sense as, P=, , F, A, , ∆F, ∆A, , (10.2), , Pressure is a scalar quantity. We remind the, reader that it is the component of the force, normal to the area under consideration and not, the (vector) force that appears in the numerator, in Eqs. (10.1) and (10.2). Its dimensions are, [ML–1T–2]. The SI unit of pressure is N m–2. It has, been named as pascal (Pa) in honour of the, French scientist Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) who, carried out pioneering studies on fluid pressure., A common unit of pressure is the atmosphere, (atm), i.e. the pressure exerted by the, atmosphere at sea level (1 atm = 1.013 × 105 Pa)., Another quantity, that is indispensable in, describing fluids, is the density ρ . For a fluid of, mass m occupying volume V,, m, ρ=, (10.3), V, –3, The dimensions of density are [ML ]. Its SI, unit is kg m–3. It is a positive scalar quantity. A, liquid is largely incompressible and its density, is therefore, nearly constant at all pressures., Gases, on the other hand exhibit a large, variation in densities with pressure., The density of water at 4 o C (277 K) is, 1.0 × 103 kg m–3. The relative density of a, substance is the ratio of its density to the, density of water at 4oC. It is a dimensionless, positive scalar quantity. For example the relative, density of aluminium is 2.7. Its density is, 2.7 × 103 kg m–3. The densities of some common, fluids are displayed in Table 10.1., Table 10.1 Densities of some common fluids, at STP*, , If F is the magnitude of this normal force on the, piston of area A then the average pressure Pav, is defined as the normal force acting per unit, area., Pav =, , lim, ∆A →0, , (10.1), , * STP means standard temperature (00C) and 1 atm pressure., , 2019-20

Page 18 :

252, , PHYSICS, , Example 10.1, The two thigh bones, (femurs), each of cross-sectional area10 cm2, support the upper part of a human body of, mass 40 kg. Estimate the average pressure, sustained by the femurs., , t, , Answer, Total cross-sectional area of the, femurs is A = 2 × 10 cm2 = 20 × 10–4 m2. The, force acting on them is F = 40 kg wt = 400 N, (taking g = 10 m s –2). This force is acting, vertically down and hence, normally on the, femurs. Thus, the average pressure is, Pav =, , F, = 2 × 105 N m −2, A, , t, , 10.2.1 Pascal’s Law, The French scientist Blaise Pascal observed that, the pressure in a fluid at rest is the same at all, points if they are at the same height. This fact, may be demonstrated in a simple way., , this element of area corresponding to the normal, forces Fa, Fb and Fc as shown in Fig. 10.2 on the, faces BEFC, ADFC and ADEB denoted by Aa, Ab, and Ac respectively. Then, Fb sinθ = Fc,, Fb cosθ = Fa (by equilibrium), Ab sinθ = Ac, Ab cosθ = Aa (by geometry), Thus,, Fb Fc, F, =, = a ;, Ab Ac Aa, , Pb = Pc = Pa, , (10.4), , Hence, pressure exerted is same in all, directions in a fluid at rest. It again reminds us, that like other types of stress, pressure is not a, vector quantity. No direction can be assigned, to it. The force against any area within (or, bounding) a fluid at rest and under pressure is, normal to the area, regardless of the orientation, of the area., Now consider a fluid element in the form of a, horizontal bar of uniform cross-section. The bar, is in equilibrium. The horizontal forces exerted, at its two ends must be balanced or the, pressure at the two ends should be equal. This, proves that for a liquid in equilibrium the, pressure is same at all points in a horizontal, plane. Suppose the pressure were not equal in, different parts of the fluid, then there would be, a flow as the fluid will have some net force, acting on it. Hence in the absence of flow the, pressure in the fluid must be same everywhere, in a horizontal plane., 10.2.2 Variation of Pressure with Depth, , Fig. 10.2 Proof of Pascal’s law. ABC-DEF is an, element of the interior of a fluid at rest., This element is in the form of a rightangled prism. The element is small so that, the effect of gravity can be ignored, but it, has been enlarged for the sake of clarity., , Fig. 10.2 shows an element in the interior of, a fluid at rest. This element ABC-DEF is in the, form of a right-angled prism. In principle, this, prismatic element is very small so that every, part of it can be considered at the same depth, from the liquid surface and therefore, the effect, of the gravity is the same at all these points., But for clarity we have enlarged this element., The forces on this element are those exerted by, the rest of the fluid and they must be normal to, the surfaces of the element as discussed above., Thus, the fluid exerts pressures Pa, Pb and Pc on, , 2019-20, , Consider a fluid at rest in a container. In, Fig. 10.3 point 1 is at height h above a point 2., The pressures at points 1 and 2 are P1 and P2, respectively. Consider a cylindrical element of, fluid having area of base A and height h. As the, fluid is at rest the resultant horizontal forces, should be zero and the resultant vertical forces, should balance the weight of the element. The, forces acting in the vertical direction are due to, the fluid pressure at the top (P 1A) acting, downward, at the bottom (P2A) acting upward., If mg is weight of the fluid in the cylinder we, have, (P2 − P1) A = mg, (10.5), Now, if ρ is the mass density of the fluid, we, have the mass of fluid to be m = ρV= ρhA so, that, P2 −P1= ρgh, (10.6)

Page 19 :

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF FLUIDS, , 253, , Fig 10.4 Illustration of hydrostatic paradox. The, three vessels A, B and C contain different, amounts of liquids, all upto the same, height., , t, Fig.10.3 Fluid under gravity. The effect of gravity is, illustrated through pressure on a vertical, cylindrical column., , Pressure difference depends on the vertical, distance h between the points (1 and 2), mass, density of the fluid ρ and acceleration due to, gravity g. If the point 1 under discussion is, shifted to the top of the fluid (say, water), which, is open to the atmosphere, P1 may be replaced, by atmospheric pressure (Pa) and we replace P2, by P. Then Eq. (10.6) gives, P = Pa + ρgh, , (10.7), , Thus, the pressure P, at depth below the, surface of a liquid open to the atmosphere is, greater than atmospheric pressure by an, amount ρgh. The excess of pressure, P −Pa, at, depth h is called a gauge pressure at that point., The area of the cylinder is not appearing in, the expression of absolute pressure in Eq. (10.7)., Thus, the height of the fluid column is important, and not cross-sectional or base area or the shape, of the container. The liquid pressure is the same, at all points at the same horizontal level (same, depth). The result is appreciated through the, example of hydrostatic paradox. Consider three, vessels A, B and C [Fig.10.4] of different shapes., They are connected at the bottom by a horizontal, pipe. On filling with water, the level in the three, vessels is the same, though they hold different, amounts of water. This is so because water at, the bottom has the same pressure below each, section of the vessel., , Example 10.2 What is the pressure on a, swimmer 10 m below the surface of a lake?, , Answer Here, h = 10 m and ρ = 1000 kg m-3. Take g = 10 m s–2, From Eq. (10.7), P = Pa + ρgh, = 1.01 × 105 Pa + 1000 kg m–3 × 10 m s–2 × 10 m, = 2.01 × 105 Pa, ≈ 2 atm, This is a 100% increase in pressure from, surface level. At a depth of 1 km, the increase, in pressure is 100 atm! Submarines are designed, to withstand such enormous pressures., t, 10.2.3 Atmospheric Pressure and, Gauge Pressure, The pressure of the atmosphere at any point is, equal to the weight of a column of air of unit, cross-sectional area extending from that point, to the top of the atmosphere. At sea level, it is, 1.013 × 10 5 Pa (1 atm). Italian scientist, Evangelista Torricelli (1608 –1647) devised for, the first time a method for measuring, atmospheric pressure. A long glass tube closed, at one end and filled with mercury is inverted, into a trough of mercury as shown in Fig.10.5 (a)., This device is known as ‘mercury barometer’., The space above the mercury column in the tube, contains only mercury vapour whose pressure, P is so small that it may be neglected. Thus,, the pressure at Point A=0. The pressure inside, the coloumn at Point B must be the same as the, pressure at Point C, which is atmospheric, pressure, Pa., Pa = ρgh, (10.8), where ρ is the density of mercury and h is the, height of the mercury column in the tube., , 2019-20

Page 20 :

254, , PHYSICS, , (b) The open tube manometer, Fig 10.5 Two pressure measuring devices., , Pressure is same at the same level on both, sides of the U-tube containing a fluid. For, liquids, the density varies very little over wide, ranges in pressure and temperature and we can, treat it safely as a constant for our present, purposes. Gases on the other hand, exhibits, large variations of densities with changes in, pressure and temperature. Unlike gases, liquids, are, therefore, largely treated as incompressible., t, , In the experiment it is found that the mercury, column in the barometer has a height of about, 76 cm at sea level equivalent to one atmosphere, (1 atm). This can also be obtained using the, value of ρ in Eq. (10.8). A common way of stating, pressure is in terms of cm or mm of mercury, (Hg). A pressure equivalent of 1 mm is called a, torr (after Torricelli)., 1 torr = 133 Pa., The mm of Hg and torr are used in medicine, and physiology. In meteorology, a common unit, is the bar and millibar., 1 bar = 105 Pa, An open tube manometer is a useful, instrument for measuring pressure differences., It consists of a U-tube containing a suitable, liquid i.e., a low density liquid (such as oil) for, measuring small pressure differences and a, high density liquid (such as mercury) for large, pressure differences. One end of the tube is open, to the atmosphere and the other end is, connected to the system whose pressure we want, to measure [see Fig. 10.5 (b)]. The pressure P at, A is equal to pressure at point B. What we, normally measure is the gauge pressure, which, is P −Pa, given by Eq. (10.8) and is proportional, to manometer height h., , Example 10.3 The density of the, atmosphere at sea level is 1.29 kg/m3., Assume that it does not change with, altitude. Then how high would the, atmosphere extend?, , Answer We use Eq. (10.7), ρgh = 1.29 kg m–3 × 9.8 m s2 × h m = 1.01 × 105 Pa, ∴ h = 7989 m ≈ 8 km, In reality the density of air decreases with, height. So does the value of g. The atmospheric, cover extends with decreasing pressure over, 100 km. We should also note that the sea level, atmospheric pressure is not always 760 mm of, Hg. A drop in the Hg level by 10 mm or more is a, sign of an approaching storm., t, t, Fig 10.5 (a) The mercury barometer., , 2019-20, , Example 10.4 At a depth of 1000 m in an, ocean (a) what is the absolute pressure?, (b) What is the gauge pressure? (c) Find, the force acting on the window of area, 20 cm × 20 cm of a submarine at this depth,, the interior of which is maintained at sealevel atmospheric pressure. (The density of, sea water is 1.03 × 10 3 kg m -3 ,, g = 10 m s–2.)

Page 21 :

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF FLUIDS, , Answer Here h = 1000 m and ρ = 1.03 × 103 kg m-3., (a) From Eq. (10.6), absolute pressure, P = Pa + ρgh, = 1.01 × 105 Pa, + 1.03 × 103 kg m–3 × 10 m s–2 × 1000 m, = 104.01 × 105 Pa, ≈ 104 atm, (b) Gauge pressure is P −Pa = ρgh = Pg, Pg = 1.03 × 103 kg m–3 × 10 ms2 × 1000 m, = 103 × 105 Pa, ≈ 103 atm, (c) The pressure outside the submarine is, P = Pa + ρgh and the pressure inside it is Pa., Hence, the net pressure acting on the, window is gauge pressure, Pg = ρgh. Since, the area of the window is A = 0.04 m2, the, force acting on it is, F = Pg A = 103 × 105 Pa × 0.04 m2 = 4.12 × 105 N, t, 10.2.4 Hydraulic Machines, Let us now consider what happens when we, change the pressure on a fluid contained in a, vessel. Consider a horizontal cylinder with a, piston and three vertical tubes at different, points [Fig. 10.6 (a)]. The pressure in the, horizontal cylinder is indicated by the height of, liquid column in the vertical tubes. It is necessarily, the same in all. If we push the piston, the fluid level, rises in all the tubes, again reaching the same level, in each one of them., , 255, , Fig 10.6 (a) Whenever external pressure is applied, on any part of a fluid in a vessel, it is, equally transmitted in all directions., , This indicates that when the pressure on the, cylinder was increased, it was distributed, uniformly throughout. We can say whenever, external pressure is applied on any part of a, fluid contained in a vessel, it is transmitted, undiminished and equally in all directions., This is another form of the Pascal’s law and it, has many applications in daily life., A number of devices, such as hydraulic lift, and hydraulic brakes, are based on the Pascal’s, law. In these devices, fluids are used for, transmitting pressure. In a hydraulic lift, as, shown in Fig. 10.6 (b), two pistons are separated, by the space filled with a liquid. A piston of small, cross-section A1 is used to exert a force F1 directly, F1, on the liquid. The pressure P = A is, 1, transmitted throughout the liquid to the larger, cylinder attached with a larger piston of area A2,, which results in an upward force of P × A2., Therefore, the piston is capable of supporting a, large force (large weight of, say a car, or a truck,, , Archemedes’ Principle, Fluid appears to provide partial support to the objects placed in it. When a body is wholly or partially, immersed in a fluid at rest, the fluid exerts pressure on the surface of the body in contact with the, fluid. The pressure is greater on lower surfaces of the body than on the upper surfaces as pressure in, a fluid increases with depth. The resultant of all the forces is an upward force called buoyant force., Suppose that a cylindrical body is immersed in the fluid. The upward force on the bottom of the body, is more than the downward force on its top. The fluid exerts a resultant upward force or buoyant force, on the body equal to (P2 – P1) × A (Fig. 10.3). We have seen in equation 10.4 that (P2-P1)A = ρghA. Now,, hA is the volume of the solid and ρhA is the weight of an equivaliant volume of the fluid. (P2-P1)A = mg., Thus, the upward force exerted is equal to the weight of the displaced fluid., The result holds true irrespective of the shape of the object and here cylindrical object is considered, only for convenience. This is Archimedes’ principle. For totally immersed objects the volume of the, fluid displaced by the object is equal to its own volume. If the density of the immersed object is more, than that of the fluid, the object will sink as the weight of the body is more than the upward thrust. If, the density of the object is less than that of the fluid, it floats in the fluid partially submerged. To, calculate the volume submerged, suppose the total volume of the object is Vs and a part Vp of it is, submerged in the fluid. Then, the upward force which is the weight of the displaced fluid is ρ fgVp,, which must equal the weight of the body; ρ sgVs = ρ fgVpor ρs/ρ f = Vp/Vs The apparent weight of the, floating body is zero., This principle can be summarised as; ‘the loss of weight of a body submerged (partially or fully) in, a fluid is equal to the weight of the fluid displaced’., , 2019-20

Page 22 :

256, , PHYSICS, , F1 A2, A1 . By, changing the force at A1, the platform can be, moved up or down. Thus, the applied force has, , placed on the platform) F2 = PA2 =, , (b) Water is considered to be per fectly, incompressible. Volume covered by the, movement of smaller piston inwards is equal to, volume moved outwards due to the larger piston., , L1 A1 = L2 A2, , A2, been increased by a factor of A and this factor, 1, is the mechanical advantage of the device. The, example below clarifies it., , j 0.67 × 10-2 m = 0.67 cm, Note, atmospheric pressure is common to both, pistons and has been ignored., t, Example 10.6 In a car lift compressed air, exerts a force F1 on a small piston having, a radius of 5.0 cm. This pressure is, transmitted to a second piston of radius, 15 cm (Fig 10.7). If the mass of the car to, be lifted is 1350 kg, calculate F1. What is, the pressure necessary to accomplish this, task? (g = 9.8 ms-2)., , t, Fig 10.6 (b) Schematic diagram illustrating the principle, behind the hydraulic lift, a device used to, lift heavy loads., , Answer Since pressure is transmitted, undiminished throughout the fluid,, , Example 10.5 Two syringes of different, cross-sections (without needles) filled with, water are connected with a tightly fitted, rubber tube filled with water. Diameters of, the smaller piston and larger piston are 1.0, cm and 3.0 cm respectively. (a) Find the, force exerted on the larger piston when a, force of 10 N is applied to the smaller piston., (b) If the smaller piston is pushed in through, 6.0 cm, how much does the larger piston, move out?, , = 1470 N, ≈ 1.5 × 103 N, The air pressure that will produce this, force is, , t, , Answer (a) Since pressure is transmitted, undiminished throughout the fluid,, , (, (, , ), ), , 2, , π 3 /2 × 10–2 m, A, F2 = 2 F1 =, × 10 N, 2, A1, π 1/2 × 10–2 m, = 90 N, , This is almost double the atmospheric, pressure., t, Hydraulic brakes in automobiles also work on, the same principle. When we apply a little force, on the pedal with our foot the master piston, , Archimedes (287–212 B.C.), Archimedes was a Greek philosopher, mathematician, scientist and engineer. He, invented the catapult and devised a system of pulleys and levers to handle heavy, loads. The king of his native city Syracuse, Hiero II, asked him to determine if his gold, crown was alloyed with some cheaper metal, such as silver without damaging the crown., The partial loss of weight he experienced while lying in his bathtub suggested a solution, to him. According to legend, he ran naked through the streets of Syracuse, exclaiming “Eureka,, eureka!”, which means “I have found it, I have found it!”, , 2019-20

Page 23 :

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF FLUIDS, , moves inside the master cylinder, and the, pressure caused is transmitted through the, brake oil to act on a piston of larger area. A large, force acts on the piston and is pushed down, expanding the brake shoes against brake lining., In this way, a small force on the pedal produces, a large retarding force on the wheel. An, important advantage of the system is that the, pressure set up by pressing pedal is transmitted, equally to all cylinders attached to the four, wheels so that the braking effort is equal on, all wheels., 10.3 STREAMLINE FLOW, So far we have studied fluids at rest. The study, of the fluids in motion is known as fluid, dynamics. When a water tap is turned on slowly,, the water flow is smooth initially, but loses its, smoothness when the speed of the outflow is, increased. In studying the motion of fluids, we, focus our attention on what is happening to, various fluid particles at a particular point in, space at a particular time. The flow of the fluid, is said to be steady if at any given point, the, velocity of each passing fluid particle remains, constant in time. This does not mean that the, velocity at different points in space is same. The, velocity of a particular particle may change as it, moves from one point to another. That is, at some, other point the particle may have a different, velocity, but every other particle which passes, the second point behaves exactly as the previous, particle that has just passed that point. Each, particle follows a smooth path, and the paths of, the particles do not cross each other., , Fig. 10.7 The meaning of streamlines. (a) A typical, trajectory of a fluid particle., (b) A region of streamline flow., , 257, , The path taken by a fluid particle under a, steady flow is a streamline. It is defined as a, curve whose tangent at any point is in the, direction of the fluid velocity at that point., Consider the path of a particle as shown in, Fig.10.7 (a), the curve describes how a fluid, particle moves with time. The curve PQ is like a, permanent map of fluid flow, indicating how the, fluid streams. No two streamlines can cross, for, if they do, an oncoming fluid particle can go, either one way or the other and the flow would, not be steady. Hence, in steady flow, the map of, flow is stationary in time. How do we draw closely, spaced streamlines ? If we intend to show, streamline of every flowing particle, we would, end up with a continuum of lines. Consider planes, perpendicular to the direction of fluid flow e.g.,, at three points P, R and Q in Fig.10.7 (b). The, plane pieces are so chosen that their boundaries, be determined by the same set of streamlines., This means that number of fluid particles, crossing the surfaces as indicated at P, R and Q, is the same. If area of cross-sections at these, points are AP,AR and AQ and speeds of fluid, particles are vP, vR and vQ, then mass of fluid, ∆mP crossing at AP in a small interval of time ∆t, is ρ PAPvP ∆t. Similarly mass of fluid ∆mR flowing, or crossing at AR in a small interval of time ∆t is, ρ RARvR ∆t and mass of fluid ∆mQ is ρ QAQvQ ∆t, crossing at AQ. The mass of liquid flowing out, equals the mass flowing in, holds in all cases., Therefore,, ρ PAPvP∆t = ρ RARvR∆t = ρ QAQvQ∆t, (10.9), For flow of incompressible fluids, ρP = ρR = ρQ, Equation (10.9) reduces to, APvP = ARvR = AQvQ, (10.10), which is called the equation of continuity and, it is a statement of conservation of mass in flow, of incompressible fluids. In general, Av = constant, (10.11), Av gives the volume flux or flow rate and, remains constant throughout the pipe of flow., Thus, at narrower portions where the, streamlines are closely spaced, velocity, increases and its vice versa. From (Fig 10.7b) it, is clear that AR > AQ or vR < vQ, the fluid is, accelerated while passing from R to Q. This is, associated with a change in pressure in fluid, flow in horizontal pipes., Steady flow is achieved at low flow speeds., Beyond a limiting value, called critical speed,, this flow loses steadiness and becomes, turbulent. One sees this when a fast flowing, , 2019-20

Page 24 :

258, , PHYSICS, , stream encounters rocks, small foamy, whirlpool-like regions called ‘white water, rapids are formed., Figure 10.8 displays streamlines for some, typical flows. For example, Fig. 10.8(a) describes, a laminar flow where the velocities at different, points in the fluid may have dif ferent, magnitudes but their directions are parallel., Figure 10.8 (b) gives a sketch of turbulent flow., , Fig. 10.8 (a) Some streamlines for fluid flow., (b) A jet of air striking a flat plate placed, perpendicular to it. This is an example, of turbulent flow., , 10.4 BERNOULLI’S PRINCIPLE, Fluid flow is a complex phenomenon. But we, can obtain some useful properties for steady, or streamline flows using the conservation, of energy., Consider a fluid moving in a pipe of varying, cross-sectional area. Let the pipe be at varying, heights as shown in Fig. 10.9. We now suppose, that an incompressible fluid is flowing through, the pipe in a steady flow. Its velocity must, change as a consequence of equation of, continuity. A force is required to produce this, acceleration, which is caused by the fluid, surrounding it, the pressure must be different, in different regions. Bernoulli’s equation is a, general expression that relates the pressure, difference between two points in a pipe to both, velocity changes (kinetic energy change) and, elevation (height) changes (potential energy, , change). The Swiss Physicist Daniel Bernoulli, developed this relationship in 1738., Consider the flow at two regions 1 (i.e., BC), and 2 (i.e., DE). Consider the fluid initially lying, between B and D. In an infinitesimal time, interval ∆t, this fluid would have moved. Suppose, v1 is the speed at B and v2 at D, then fluid initially, at B has moved a distance v1∆t to C (v1∆t is small, enough to assume constant cross-section along, BC). In the same interval ∆t the fluid initially at, D moves to E, a distance equal to v2∆t. Pressures, P1 and P2 act as shown on the plane faces of, areas A1 and A2 binding the two regions. The, work done on the fluid at left end (BC) is W1 =, P1A1(v1∆t) = P1∆V. Since the same volume ∆V, passes through both the regions (from the, equation of continuity) the work done by the fluid, at the other end (DE) is W2 = P2A2(v2∆t) = P2∆V or,, the work done on the fluid is –P2∆V. So the total, work done on the fluid is, W1 – W2 = (P1− P2) ∆V, Part of this work goes into changing the kinetic, energy of the fluid, and part goes into changing, the gravitational potential energy. If the density, of the fluid is ρ and ∆m = ρA1v1∆t = ρ∆V is the, mass passing through the pipe in time ∆t, then, change in gravitational potential energy is, ∆U = ρg∆V (h2 − h1), The change in its kinetic energy is, ∆K =, , ρ ∆V (v22 − v12), , We can employ the work – energy theorem, (Chapter 6) to this volume of the fluid and, this yields, , 1, (P1−P2) ∆V = ρ ∆V (v22 −v12) + ρg∆V (h2 −h1), 2, We now divide each term by ∆V to obtain, , 1, (P1− P2) = ρ (v22 − v12) + ρg (h2 − h1), 2, , Daniel Bernoulli (1700 –1782), Daniel Bernoulli was a Swiss scientist and mathematician, who along with Leonard, Euler had the distinction of winning the French Academy prize for mathematics, 10 times. He also studied medicine and served as a professor of anatomy and, botany for a while at Basle, Switzerland. His most well-known work was in, hydrodynamics, a subject he developed from a single principle: the conservation of, energy. His work included calculus, probability, the theory of vibrating strings,, and applied mathematics. He has been called the founder of mathematical physics., , 2019-20, , 1, , 2

Page 25 :

MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF FLUIDS, , 259, , We can rearrange the above terms to obtain, , 1, P1 + ρv12 + ρgh1 = P2+, 2, , 1, ρv22 + ρgh2, 2, (10.12), This is Bernoulli’s equation. Since 1 and 2, refer to any two locations along the pipeline,, we may write the expression in general as, 1, P + ρv2 + ρgh = constant, 2, , (10.13), , restriction on application of Bernoulli theorem, is that the fluids must be incompressible, as, the elastic energy of the fluid is also not taken, into consideration. In practice, it has a large, number of useful applications and can help, explain a wide variety of phenomena for low, viscosity incompressible fluids. Bernoulli’s, equation also does not hold for non-steady or, turbulent flows, because in that situation, velocity and pressure are constantly fluctuating, in time., When a fluid is at rest i.e., its velocity is zero, everywhere, Bernoulli’s equation becomes, P1 + ρgh1 = P2 + ρgh2, (P1− P2) = ρg (h2 − h1), which is same as Eq. (10.6)., 10.4.1 Speed of Efflux: Torricelli’s Law, , Fig. 10.9 The flow of an ideal fluid in a pipe of, varying cross section. The fluid in a, section of length v1∆t moves to the section, of length v2∆t in time ∆t., , The word efflux means fluid outflow. Torricelli, discovered that the speed of efflux from an open, tank is given by a formula identical to that of a, freely falling body. Consider a tank containing, a liquid of density ρ with a small hole in its side, at a height y1 from the bottom (see Fig. 10.10)., The air above the liquid, whose surface is at, height y2, is at pressure P. From the equation, of continuity [Eq. (10.10)] we have, v1 A1 = v2 A2, , In words, the Bernoulli’s relation may be, stated as follows: As we move along a streamline, the sum of the pressure (P), the kinetic energy, , v2 =, , A1, v, A2 1, , ρv 2 , per unit volume 2 and the potential energy, , , , per unit volume (ρgh) remains a constant., Note that in applying the energy conservation, principle, there is an assumption that no energy, is lost due to friction. But in fact, when fluids, flow, some energy does get lost due to internal, friction. This arises due to the fact that in a, fluid flow, the different layers of the fluid flow, with different velocities. These layers exert, frictional forces on each other resulting in a loss, of energy. This property of the fluid is called, viscosity and is discussed in more detail in a, later section. The lost kinetic energy of the fluid, gets converted into heat energy. Thus,, Bernoulli’s equation ideally applies to fluids with, zero viscosity or non-viscous fluids. Another, , Fig. 10.10 Torricelli’s law. The speed of efflux, v1,, from the side of the container is given by, the application of Bernoulli’s equation., If the container is open at the top to the, atmosphere then v1 = 2 g h ., , 2019-20

Page 26 :

260, , PHYSICS, , If the cross-sectional area of the tank A2 is, much larger than that of the hole (A2 >>A1), then, we may take the fluid to be approximately at rest, at the top, i.e., v2 = 0. Now, applying the Bernoulli, equation at points 1 and 2 and noting that at, the hole P1 = Pa, the atmospheric pressure, we, have from Eq. (10.12), , A, a, , 2, 1, , h, , 1, Pa + ρ v12 + ρ g y1 = P + ρ g y2, 2, Taking y2 – y1 = h we have, v1 = 2 g h +, , 2 ( P − Pa ), , (10.14), , ρ, , Fig. 10.11 A schematic diagram of Venturi-meter., , When P >>Pa and 2 g h may be ignored, the, speed of efflux is determined by the container, pressure. Such a situation occurs in rocket, propulsion. On the other hand, if the tank is, open to the atmosphere, then P = Pa and, v1 = 2g h, , (10.15), , This is also the speed of a freely falling body., Equation (10.15) represents Torricelli’s law., 10.4.2 Venturi-meter, The Venturi-meter is a device to measure the, flow speed of incompressible fluid. It consists of, a tube with a broad diameter and a small, constriction at the middle as shown in, Fig. (10.11). A manometer in the form of a, U-tube is also attached to it, with one arm at, the broad neck point of the tube and the other, at constriction as shown in Fig. (10.11). The, manometer contains a liquid of density ρ m. The, speed v1 of the liquid flowing through the tube, at the broad neck area A is to be measured, from equation of continuity Eq. (10.10) the speed, at the constriction becomes v 2 =, , 1, P1– P2 = ρ mgh =, 2, , ρv1, , 2, , A 2, , – 1, a , , , So that the speed of fluid at wide neck is, –½, , A 2, , – 1 , v 1=, (10.17), a , , The principle behind this meter has many, applications. The carburetor of automobile has, a Venturi channel (nozzle) through which air, flows with a high speed. The pressure is then, lowered at the narrow neck and the petrol, (gasoline) is sucked up in the chamber to provide, the correct mixture of air to fuel necessary for, combustion. Filter pumps or aspirators, Bunsen, burner, atomisers and sprayers [See Fig. 10.12], used for perfumes or to spray insecticides work, on the same principle., 2 ρm gh , , , ρ , , , A, v1 . Then, a, , using Bernoulli’s equation (Eq.10.12) for (h1=h2),, we get, P1+, , 1, 2, , ρv12 = P2+, , 1, 2, , ρv12 (A/a)2, , So that, , A 2, , ρv12 a – 1, (10.16), , , This pressure difference causes the fluid in, the U-tube connected at the narrow neck to rise, in comparison to the other arm. The difference, in height h measure the pressure difference., , 1, P1- P2 =, 2, , 2019-20, , Fig. 10.12 The spray gun. Piston forces air at high, speeds causing a lowering of pressure, at the neck of the container.

Page 27 :