Page 1 :

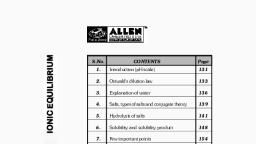

192, , CHEMISTRY, , UNIT 7, , EQUILIBRIUM, , After studying this unit you will be, able to, • identify dynamic nature of, equilibrium involved in physical, and chemical processes;, • state the law of equilibrium;, • explain characteristics of, equilibria involved in physical, and chemical processes;, • write, expressions, for, equilibrium constants;, • establish a relationship between, Kp and K c ;, • explain various factors that, affect the equilibrium state of a, reaction;, • classify substances as acids or, bases according to Arrhenius,, Bronsted-Lowry and Lewis, concepts;, • classify acids and bases as weak, or strong in terms of their, ionization constants;, • explain the dependence of, degree of ionization on, concentration of the electrolyte, and that of the common ion;, • describe, pH, scale, for, representing hydrogen ion, concentration;, • explain ionisation of water and, its duel role as acid and base;, • describe ionic product (Kw ) and, pKw for water;, • appreciate use of buffer, solutions;, • calculate solubility product, constant., , Chemical equilibria are important in numerous biological, and environmental processes. For example, equilibria, involving O2 molecules and the protein hemoglobin play a, crucial role in the transport and delivery of O2 from our, lungs to our muscles. Similar equilibria involving CO, molecules and hemoglobin account for the toxicity of CO., When a liquid evaporates in a closed container,, molecules with relatively higher kinetic energy escape the, liquid surface into the vapour phase and number of liquid, molecules from the vapour phase strike the liquid surface, and are retained in the liquid phase. It gives rise to a constant, vapour pressure because of an equilibrium in which the, number of molecules leaving the liquid equals the number, returning to liquid from the vapour. We say that the system, has reached equilibrium state at this stage. However, this, is not static equilibrium and there is a lot of activity at the, boundary between the liquid and the vapour. Thus, at, equilibrium, the rate of evaporation is equal to the rate of, condensation. It may be represented by, H2O (l) � H2O (vap), The double half arrows indicate that the processes in, both the directions are going on simultaneously. The mixture, of reactants and products in the equilibrium state is called, an equilibrium mixture., Equilibrium can be established for both physical, processes and chemical reactions. The reaction may be fast, or slow depending on the experimental conditions and the, nature of the reactants. When the reactants in a closed vessel, at a particular temperature react to give products, the, concentrations of the reactants keep on decreasing, while, those of products keep on increasing for some time after, which there is no change in the concentrations of either of, the reactants or products. This stage of the system is the, dynamic equilibrium and the rates of the forward and, , 2021-22

Page 2 :

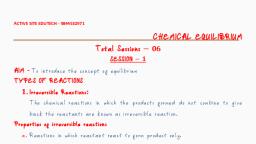

EQUILIBRIUM, , 193, , reverse reactions become equal. It is due to, this dynamic equilibrium stage that there is, no change in the concentrations of various, species in the reaction mixture. Based on the, extent to which the reactions proceed to reach, the state of chemical equilibrium, these may, be classified in three groups., (i) The reactions that proceed nearly to, completion and only negligible, concentrations of the reactants are left. In, some cases, it may not be even possible to, detect these experimentally., (ii) The reactions in which only small amounts, of products are formed and most of the, reactants remain unchanged at, equilibrium stage., (iii) The reactions in which the concentrations, of the reactants and products are, comparable, when the system is in, equilibrium., The extent of a reaction in equilibrium, varies with the experimental conditions such, as concentrations of reactants, temperature,, etc. Optimisation of the operational conditions, is very important in industry and laboratory, so that equilibrium is favorable in the, direction of the desired product. Some, important aspects of equilibrium involving, physical and chemical processes are dealt in, this unit along with the equilibrium involving, ions in aqueous solutions which is called as, ionic equilibrium., 7.1 EQUILIBRIUM, IN, PHYSICAL, PROCESSES, The characteristics of system at equilibrium, are better understood if we examine some, physical processes. The most familiar, examples are phase transformation, processes, e.g.,, solid, liquid, solid, , liquid, gas, gas, , 7.1.1 Solid-Liquid Equilibrium, Ice and water kept in a perfectly insulated, thermos flask (no exchange of heat between, its contents and the surroundings) at 273K, , and the atmospheric pressure are in, equilibrium state and the system shows, interesting characteristic features. We observe, that the mass of ice and water do not change, with time and the temperature remains, constant. However, the equilibrium is not, static. The intense activity can be noticed at, the boundary between ice and water., Molecules from the liquid water collide against, ice and adhere to it and some molecules of ice, escape into liquid phase. There is no change, of mass of ice and water, as the rates of transfer, of molecules from ice into water and of reverse, transfer from water into ice are equal at, atmospheric pressure and 273 K., It is obvious that ice and water are in, equilibrium only at particular temperature, and pressure. For any pure substance at, atmospheric pressure, the temperature at, which the solid and liquid phases are at, equilibrium is called the normal melting point, or normal freezing point of the substance., The system here is in dynamic equilibrium and, we can infer the following:, (i) Both the opposing processes occur, simultaneously., (ii) Both the processes occur at the same rate, so that the amount of ice and water, remains constant., 7.1.2 Liquid-Vapour Equilibrium, This equilibrium can be better understood if, we consider the example of a transparent box, carrying a U-tube with mercury (manometer)., Drying agent like anhydrous calcium chloride, (or phosphorus penta-oxide) is placed for a, few hours in the box. After removing the, drying agent by tilting the box on one side, a, watch glass (or petri dish) containing water is, quickly placed inside the box. It will be, observed that the mercury level in the right, limb of the manometer slowly increases and, finally attains a constant value, that is, the, pressure inside the box increases and reaches, a constant value. Also the volume of water in, the watch glass decreases (Fig. 7.1). Initially, there was no water vapour (or very less) inside, the box. As water evaporated the pressure in, the box increased due to addition of water, , 2021-22

Page 3 :

194, , CHEMISTRY, , Fig.7.1 Measuring equilibrium vapour pressure of water at a constant temperature, , molecules into the gaseous phase inside the, box. The rate of evaporation is constant., However, the rate of increase in pressure, decreases with time due to condensation of, vapour into water. Finally it leads to an, equilibrium condition when there is no net, evaporation. This implies that the number of, water molecules from the gaseous state into, the liquid state also increases till the, equilibrium is attained i.e.,, rate of evaporation= rate of condensation, H2O (vap), H2O(l), At equilibrium the pressure exerted by the, water molecules at a given temperature, remains constant and is called the equilibrium, vapour pressure of water (or just vapour, pressure of water); vapour pressure of water, increases with temperature. If the above, experiment is repeated with methyl alcohol,, acetone and ether, it is observed that different, liquids have different equilibrium vapour, pressures at the same temperature, and the, liquid which has a higher vapour pressure is, more volatile and has a lower boiling point., If we expose three watch glasses, containing separately 1mL each of acetone,, ethyl alcohol, and water to atmosphere and, repeat the experiment with different volumes, of the liquids in a warmer room, it is observed, that in all such cases the liquid eventually, disappears and the time taken for complete, evaporation depends on (i) the nature of the, liquid, (ii) the amount of the liquid and (iii) the, temperature. When the watch glass is open to, the atmosphere, the rate of evaporation, remains constant but the molecules are, , dispersed into large volume of the room. As a, consequence the rate of condensation from, vapour to liquid state is much less than the, rate of evaporation. These are open systems, and it is not possible to reach equilibrium in, an open system., Water and water vapour are in equilibrium, position at atmospheric pressure (1.013 bar), and at 100°C in a closed vessel. The boiling, point of water is 100°C at 1.013 bar pressure., For any pure liquid at one atmospheric, pressure (1.013 bar), the temperature at, which the liquid and vapours are at, equilibrium is called normal boiling point of, the liquid. Boiling point of the liquid depends, on the atmospheric pressure. It depends on, the altitude of the place; at high altitude the, boiling point decreases., 7.1.3 Solid – Vapour Equilibrium, Let us now consider the systems where solids, sublime to vapour phase. If we place solid iodine, in a closed vessel, after sometime the vessel gets, filled up with violet vapour and the intensity of, colour increases with time. After certain time the, intensity of colour becomes constant and at this, stage equilibrium is attained. Hence solid iodine, sublimes to give iodine vapour and the iodine, vapour condenses to give solid iodine. The, equilibrium can be represented as,, I2 (vapour), I2(solid), Other examples showing this kind of, equilibrium are,, Camphor (solid) � Camphor (vapour), , 2021-22, , NH4Cl (solid) � NH4Cl (vapour), , �

Page 4 :

EQUILIBRIUM, , 195, , 7.1.4 Equilibrium Involving Dissolution of, Solid or Gases in Liquids, Solids in liquids, We know from our experience that we can, dissolve only a limited amount of salt or sugar, in a given amount of water at room, temperature. If we make a thick sugar syrup, solution by dissolving sugar at a higher, temperature, sugar crystals separate out if we, cool the syrup to the room temperature. We, call it a saturated solution when no more of, solute can be dissolved in it at a given, temperature. The concentration of the solute, in a saturated solution depends upon the, temperature. In a saturated solution, a, dynamic equilibrium exits between the solute, molecules in the solid state and in the solution:, Sugar (solution), , Sugar (solid), and, , the rate of dissolution of sugar = rate of, crystallisation of sugar., Equality of the two rates and dynamic, nature of equilibrium has been confirmed with, the help of radioactive sugar. If we drop some, radioactive sugar into saturated solution of, non-radioactive sugar, then after some time, radioactivity is observed both in the solution, and in the solid sugar. Initially there were no, radioactive sugar molecules in the solution, but due to dynamic nature of equilibrium,, there is exchange between the radioactive and, non-radioactive sugar molecules between the, two phases. The ratio of the radioactive to nonradioactive molecules in the solution increases, till it attains a constant value., Gases in liquids, When a soda water bottle is opened, some of, the carbon dioxide gas dissolved in it fizzes, out rapidly. The phenomenon arises due to, difference in solubility of carbon dioxide at, different pressures. There is equilibrium, between the molecules in the gaseous state, and the molecules dissolved in the liquid, under pressure i.e.,, CO2 (gas), , pressure of the gas above the solvent. This, amount decreases with increase of, temperature. The soda water bottle is sealed, under pressure of gas when its solubility in, water is high. As soon as the bottle is opened,, some of the dissolved carbon dioxide gas, escapes to reach a new equilibrium condition, required for the lower pressure, namely its, partial pressure in the atmosphere. This is how, the soda water in bottle when left open to the, air for some time, turns ‘flat’. It can be, generalised that:, liquid equilibrium, there is, (i) For solid, only one temperature (melting point) at, 1 atm (1.013 bar) at which the two phases, can coexist. If there is no exchange of heat, with the surroundings, the mass of the two, phases remains constant., vapour equilibrium, the, (ii) For liquid, vapour pressure is constant at a given, temperature., (iii) For dissolution of solids in liquids, the, solubility is constant at a given, temperature., (iv) For dissolution of gases in liquids, the, concentration of a gas in liquid is, proportional, to, the, pressure, (concentration) of the gas over the liquid., These observations are summarised in, Table 7.1, Table 7.1, , Some Features, Equilibria, , Process, Liquid, H2O (l), Solid, H2O (s), Solute(s), Sugar(s), , Vapour, H2O (g), Liquid, H2O (l), , Gas(g), , Gas (aq), , CO2(g), , CO2(aq), , 2021-22, , Physical, , Conclusion, pH2Oconstant at given, temperature, Melting point is fixed at, constant pressure, , Solute Concentration of solute, (solution) in solution is constant, Sugar, at a given temperature, (solution), , CO2 (in solution), , This equilibrium is governed by Henry’s, law, which states that the mass of a gas, dissolved in a given mass of a solvent at, any temperature is proportional to the, , of, , [gas(aq)]/[gas(g)] is, constant at a given, temperature, [CO 2 (aq)]/[CO 2 (g)] is, constant at a given, temperature

Page 5 :

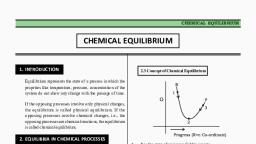

196, , CHEMISTRY, , 7.1.5 General Characteristics of Equilibria, Involving Physical Processes, For the physical processes discussed above,, following characteristics are common to the, system at equilibrium:, (i) Equilibrium is possible only in a closed, system at a given temperature., (ii) Both the opposing processes occur at the, same rate and there is a dynamic but, stable condition., (iii) All measurable properties of the system, remain constant., (iv) When equilibrium is attained for a physical, process, it is characterised by constant, value of one of its parameters at a given, temperature. Table 7.1 lists such, quantities., (v) The magnitude of such quantities at any, stage indicates the extent to which the, physical process has proceeded before, reaching equilibrium., 7.2 EQUILIBRIUM IN CHEMICAL, PROCESSES – DYNAMIC, EQUILIBRIUM, Analogous to the physical systems chemical, reactions also attain a state of equilibrium., These reactions can occur both in forward, and backward directions. When the rates of, the forward and reverse reactions become, equal, the concentrations of the reactants, and the products remain constant. This is, the stage of chemical equilibrium. This, equilibrium is dynamic in nature as it, consists of a forward reaction in which the, reactants give product(s) and reverse, reaction in which product(s) gives the, original reactants., For a better comprehension, let us, consider a general case of a reversible reaction,, A+B, , C+D, , With passage of time, there is, accumulation of the products C and D and, depletion of the reactants A and B (Fig. 7.2)., This leads to a decrease in the rate of forward, reaction and an increase in he rate of the, reverse reaction,, , Fig. 7.2 Attainment of chemical equilibrium., , Eventually, the two reactions occur at the, same rate and the system reaches a state of, equilibrium., Similarly, the reaction can reach the state of, equilibrium even if we start with only C and D;, that is, no A and B being present initially, as the, equilibrium can be reached from either direction., The dynamic nature of chemical, equilibrium can be demonstrated in the, synthesis of ammonia by Haber’s process. In, a series of experiments, Haber started with, known amounts of dinitrogen and dihydrogen, maintained at high temperature and pressure, and at regular intervals determined the, amount of ammonia present. He was, successful in determining also the, concentration of unreacted dihydrogen and, dinitrogen. Fig. 7.4 (page 191) shows that after, a certain time the composition of the mixture, remains the same even though some of the, reactants are still present. This constancy in, composition indicates that the reaction has, reached equilibrium. In order to understand, the dynamic nature of the reaction, synthesis, of ammonia is carried out with exactly the, same starting conditions (of partial pressure, and temperature) but using D2 (deuterium), in place of H2. The reaction mixtures starting, either with H2 or D2 reach equilibrium with, the same composition, except that D2 and ND3, are present instead of H2 and NH3. After, equilibrium is attained, these two mixtures, , 2021-22

Page 6 :

EQUILIBRIUM, , 197, , Dynamic Equilibrium – A Student’s Activity, Equilibrium whether in a physical or in a chemical system, is always of dynamic, nature. This can be demonstrated by the use of radioactive isotopes. This is not feasible, in a school laboratory. However this concept can be easily comprehended by performing, the following activity. The activity can be performed in a group of 5 or 6 students., Take two 100mL measuring cylinders (marked as 1 and 2) and two glass tubes, each of 30 cm length. Diameter of the tubes may be same or different in the range of, 3-5mm. Fill nearly half of the measuring cylinder -1 with coloured water (for this, purpose add a crystal of potassium permanganate to water) and keep second cylinder, (number 2) empty., Put one tube in cylinder 1 and second in cylinder 2. Immerse one tube in cylinder, 1, close its upper tip with a finger and transfer the coloured water contained in its, lower portion to cylinder 2. Using second tube, kept in 2nd cylinder, transfer the coloured, water in a similar manner from cylinder 2 to cylinder 1. In this way keep on transferring, coloured water using the two glass tubes from cylinder 1 to 2 and from 2 to 1 till you, notice that the level of coloured water in both the cylinders becomes constant., If you continue intertransferring coloured solution between the cylinders, there will, not be any further change in the levels of coloured water in two cylinders. If we take, analogy of ‘level’ of coloured water with ‘concentration’ of reactants and products in the, two cylinders, we can say the process of transfer, which continues even after the constancy, of level, is indicative of dynamic nature of the process. If we repeat the experiment taking, two tubes of different diameters we find that at equilibrium the level of coloured water in, two cylinders is different. How far diameters are responsible for change in levels in two, cylinders? Empty cylinder (2) is an indicator of no product in it at the beginning., , Fig.7.3, , Demonstrating dynamic nature of equilibrium. (a) initial stage (b) final stage after the, equilibrium is attained., , 2021-22

Page 7 :

198, , CHEMISTRY, , Fig 7.4 Depiction of equilibrium for the reaction, , N 2 ( g ) + 3H2 ( g ) � 2NH3 ( g ), (H 2, N2, NH3 and D2 , N2, ND3) are mixed, together and left for a while. Later, when this, mixture is analysed, it is found that the, concentration of ammonia is just the same as, before. However, when this mixture is, analysed by a mass spectrometer, it is found, that ammonia and all deuterium containing, forms of ammonia (NH3, NH2D, NHD2 and ND3), and dihydrogen and its deutrated forms, (H2, HD and D2) are present. Thus one can, conclude that scrambling of H and D atoms, in the molecules must result from a, continuation of the forward and reverse, reactions in the mixture. If the reaction had, simply stopped when they reached, equilibrium, then there would have been no, mixing of isotopes in this way., Use of isotope (deuterium) in the formation, of ammonia clearly indicates that chemical, reactions reach a state of dynamic, equilibrium in which the rates of forward, and reverse reactions are equal and there, is no net change in composition., Equilibrium can be attained from both, sides, whether we start reaction by taking,, H2(g) and N2(g) and get NH3(g) or by taking, NH3(g) and decomposing it into N2(g) and, H2(g)., N2(g) + 3H2(g), 2NH3(g), , 2NH3(g), N2(g) + 3H2(g), Similarly let us consider the reaction,, H2(g) + I2(g), 2HI(g). If we start with equal, initial concentration of H2 and I2, the reaction, proceeds in the forward direction and the, concentration of H2 and I2 decreases while that, of HI increases, until all of these become, constant at equilibrium (Fig. 7.5). We can also, start with HI alone and make the reaction to, proceed in the reverse direction; the, concentration of HI will decrease and, concentration of H2 and I2 will increase until, they all become constant when equilibrium is, reached (Fig.7.5). If total number of H and I, atoms are same in a given volume, the same, equilibrium mixture is obtained whether we, start it from pure reactants or pure product., , Fig.7.5 Chemical equilibrium in the reaction, H2(g) + I2(g) � 2HI(g) can be attained, from either direction, , 7.3 LAW OF CHEMICAL EQUILIBRIUM, AND EQUILIBRIUM CONSTANT, A mixture of reactants and products in the, equilibrium state is called an equilibrium, mixture. In this section we shall address a, number of important questions about the, composition of equilibrium mixtures: What is, the relationship between the concentrations of, reactants and products in an equilibrium, mixture? How can we determine equilibrium, concentrations from initial concentrations?, , 2021-22

Page 8 :

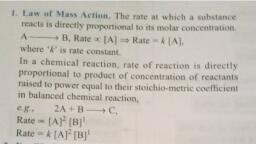

EQUILIBRIUM, , 199, , What factors can be exploited to alter the, composition of an equilibrium mixture? The, last question in particular is important when, choosing conditions for synthesis of industrial, chemicals such as H2, NH3, CaO etc., To answer these questions, let us consider, a general reversible reaction:, A+B, C+D, where A and B are the reactants, C and D are, the products in the balanced chemical, equation. On the basis of experimental studies, of many reversible reactions, the Norwegian, chemists Cato Maximillian Guldberg and Peter, Waage proposed in 1864 that the, concentrations in an equilibrium mixture are, related by the following equilibrium, equation,, , Kc =, , [C ][D], [ A ][B ], , (7.1) where Kc is the equilibrium constant, and the expression on the right side is called, the equilibrium constant expression., The equilibrium equation is also known as, the law of mass action because in the early, days of chemistry, concentration was called, “active mass”. In order to appreciate their work, better, let us consider reaction between, gaseous H2 and I2 carried out in a sealed vessel, at 731K., 2HI(g), H2(g) + I2(g), 1 mol 1 mol, 2 mol, , Six sets of experiments with varying initial, conditions were performed, starting with only, gaseous H2 and I2 in a sealed reaction vessel, in first four experiments (1, 2, 3 and 4) and, only HI in other two experiments (5 and 6)., Experiment 1, 2, 3 and 4 were performed, taking different concentrations of H2 and / or, I2, and with time it was observed that intensity, of the purple colour remained constant and, equilibrium was attained. Similarly, for, experiments 5 and 6, the equilibrium was, attained from the opposite direction., Data obtained from all six sets of, experiments are given in Table 7.2., It is evident from the experiments 1, 2, 3, and 4 that number of moles of dihydrogen, reacted = number of moles of iodine reacted =, ½ (number of moles of HI formed). Also,, experiments 5 and 6 indicate that,, [H2(g)]eq = [I2(g)]eq, Knowing the above facts, in order to, establish, a, relationship, between, concentrations of the reactants and products,, several combinations can be tried. Let us, consider the simple expression,, [HI(g)]eq / [H2(g)]eq [I2(g)]eq, It can be seen from Table 7.3 that if we, put the equilibrium concentrations of the, reactants and products, the above expression, , Table 7.2 Initial and Equilibrium Concentrations of H2, I2 and HI, , 2021-22

Page 9 :

200, , CHEMISTRY, , Table 7.3, , Expression, Involving, the, Equilibrium Concentration of, Reactants, H2(g) + I2(g), 2HI(g), , The equilibrium constant for a general, reaction,, cC + dD, aA + bB, is expressed as,, c, , d, , a, , b, , Kc = [C] [D] / [A] [B], (7.4), where [A], [B], [C] and [D] are the equilibrium, concentrations of the reactants and products., Equilibrium constant for the reaction,, 4NH3(g) + 5O2(g), as, , 4NO(g) + 6H2O(g) is written, , 4, , 6, , 4, , 5, , Kc = [NO] [H2O] / [NH3] [O2], is far from constant. However, if we consider, the expression,, [HI(g)]2eq / [H2(g)]eq [I2(g)]eq, we find that this expression gives constant, value (as shown in Table 7.3) in all the six, cases. It can be seen that in this expression, the power of the concentration for reactants, and products are actually the stoichiometric, coefficients in the equation for the chemical, reaction. Thus, for the reaction H2(g) + I2(g), 2HI(g), following equation 7.1, the equilibrium, constant Kc is written as,, 2, , Kc = [HI(g)]eq / [H2(g)]eq [I2(g)]eq, , (7.2), , Generally the subscript ‘eq’ (used for, equilibrium) is omitted from the concentration, terms. It is taken for granted that the, concentrations in the expression for Kc are, equilibrium values. We, therefore, write,, Kc = [HI(g)]2 / [H2(g)] [I2(g)], , (7.3), , The subscript ‘c’ indicates that K c is, expressed in concentrations of mol L–1., At a given temperature, the product of, concentrations of the reaction products, raised to the respective stoichiometric, coefficient in the balanced chemical, equation divided by the product of, concentrations of the reactants raised to, their individual stoichiometric coefficients, has a constant value. This is known as, the Equilibrium Law or Law of Chemical, Equilibrium., , Molar concentration of different species is, indicated by enclosing these in square bracket, and, as mentioned above, it is implied that these, are equilibrium concentrations. While writing, expression for equilibrium constant, symbol for, phases (s, l, g) are generally ignored., Let us write equilibrium constant for the, reaction, H2(g) + I2(g), 2HI(g), (7.5), as, Kc = [HI]2 / [H2] [I2] = x, (7.6), The equilibrium constant for the reverse, H2(g) + I2(g), at the same, reaction, 2HI(g), temperature is,, K′c = [H2] [I2] / [HI]2 = 1/ x = 1 / Kc, Thus, K′c = 1 / Kc, , (7.7), (7.8), , Equilibrium constant for the reverse, reaction is the inverse of the equilibrium, constant for the reaction in the forward, direction., If we change the stoichiometric coefficients, in a chemical equation by multiplying, throughout by a factor then we must make, sure that the expression for equilibrium, constant also reflects that change. For, example, if the reaction (7.5) is written as,, ½ H2(g) + ½ I2(g), HI(g), (7.9), the equilibrium constant for the above reaction, is given by, K″c = [HI] / [H2], , 1/2, , 1/2, , [I2], , 2, , 1/2, , = {[HI] / [H2][I2]}, 1/2, , 1/2, , = x = Kc, (7.10), On multiplying the equation (7.5) by n, we get, , 2021-22

Page 10 :

EQUILIBRIUM, , 201, , nH2(g) + nI2(g) D, 2nHI(g), (7.11), Therefore, equilibrium constant for the, n, reaction is equal to Kc . These findings are, summarised in Table 7.4. It should be noted, that because the equilibrium constants Kc and, K ′c have different numerical values, it is, important to specify the form of the balanced, chemical equation when quoting the value of, an equilibrium constant., , 800K. What will be Kc for the reaction, N2(g) + O2(g), 2NO(g), Solution, For the reaction equilibrium constant,, Kc can be written as,, , Kc =, , Table 7.4 Relations between Equilibrium, Constants for a General Reaction, and its Multiples., Chemical equation, c C + dD, , Kc, , cC+dD, , aA+bB, , K′c =(1/Kc ), , na A + nb B, , ncC + ndD, , K′″c = (Kc ), n, , Problem 7.1, The following concentrations were, obtained for the formation of NH3 from N2, and H 2 at equilibrium at 500K., [N2] = 1.5 × 10–2M. [H2] = 3.0 ×10–2 M and, [NH3] = 1.2 ×10–2M. Calculate equilibrium, constant., Solution, The equilibrium constant for the reaction,, 2NH3(g) can be written, N2(g) + 3H2(g), as,, , NH3 ( g ), 3, N 2 (g ) H2 ( g ), 2, , Kc =, , (1.2 × 10 ), (1.5 × 10 ) (3.0 × 10 ), −2 2, , =, , −2, , −2 3, , = 0.106 × 104 = 1.06 × 103, Problem 7.2, At equilibrium, the concentrations of, N2=3.0 × 10 –3M, O2 = 4.2 × 10–3M and, NO= 2.8 × 10–3M in a sealed vessel at, , (2.8 × 10 M ), (3.0 × 10 M) (4.2 × 10, -3, , =, , Equilibrium, constant, , aA+bB, , [NO]2, [ N 2 ][O2 ], −3, , 2, , −3, , M, , ), , = 0.622, 7.4 HOMOGENEOUS EQUILIBRIA, In a homogeneous system, all the reactants, and products are in the same phase. For, example, in the gaseous reaction,, 2NH3(g), reactants and, N 2(g) + 3H 2(g), products are in the homogeneous phase., Similarly, for the reactions,, CH3COOC2H5 (aq) + H2O (l), CH3COOH (aq), + C2H5OH (aq), –, , and, Fe3+ (aq) + SCN (aq), , Fe(SCN)2+ (aq), , all the reactants and products are in, homogeneous solution phase. We shall now, consider equilibrium constant for some, homogeneous reactions., 7.4.1 Equilibrium Constant in Gaseous, Systems, So far we have expressed equilibrium constant, of the reactions in terms of molar, concentration of the reactants and products,, and used symbol, Kc for it. For reactions, involving gases, however, it is usually more, convenient to express the equilibrium, constant in terms of partial pressure., The ideal gas equation is written as,, pV = n RT, , n, RT, V, Here, p is the pressure in Pa, n is the number, of moles of the gas, V is the volume in m3 and, T is the temperature in Kelvin, ⇒ p=, , 2021-22

Page 11 :

202, , CHEMISTRY, , Therefore,, n/V is concentration expressed in mol/m3, If concentration c, is in mol/L or mol/dm3,, and p is in bar then, p = cRT,, We can also write p = [gas]RT., Here, R= 0.0831 bar litre/mol K, At constant temperature, the pressure of, the gas is proportional to its concentration i.e.,, p ∝ [gas], For reaction in equilibrium, H2(g) + I2(g), 2HI(g), We can write either, , NH3 ( g ) [RT ], −2, = , = K c ( RT ), 3, N 2 ( g ) H 2 ( g ), 2, , or K p = K c ( RT ), , −2, , aA + bB, , Kp, , ( p )( p ), H2, , (7.12), , Further, since p HI = HI (g ) RT, pI2 = I2 ( g ) RT, pH2 = H2 ( g ) RT, Therefore,, , Kp =, , HI ( g ) [RT ], =, H2 ( g ) RT . I2 ( g ) RT, 2, , ( p )( p ), H2, , I2, , HI ( g ), = Kc, H2 (g ) I2 ( g ), , 2, , c, , d, , c +d ), , a, , b, , a +b ), , A, , B, , [C]c [D]d (RT )∆n, [ A ]a [B ]b, , ∆n, , = K c (RT ), , (7.15), , Table 7.5 Equilibrium Constants, Kp for a, Few Selected Reactions, , 2, , =, , d, , D, b, , where ∆n = (number of moles of gaseous, products) – (number of moles of gaseous, reactants) in the balanced chemical equation., It is necessary that while calculating the value, of Kp, pressure should be expressed in bar, because standard state for pressure is 1 bar., We know from Unit 1 that :, –2, 1pascal, Pa=1Nm , and 1bar = 105 Pa, Kp values for a few selected reactions at, different temperatures are given in Table 7.5, , I2, , ( pHI )2, , c, , C, a, , [C ]c [D]d (RT )(c +d )−(a +b ), [ A ]a [B ]b, , =, , 2, , cC + dD, , p )( p ) [C] [D] ( RT )(, (, =, =, ( p )( p ) [ A ] [B] (RT )(, =, , 2, , or K c =, , (7.14), , Similarly, for a general reaction, , HI ( g ), Kc =, H2 ( g ) I2 ( g ), , ( p HI ), , −2, , (7.13), , In this example, K p = K c i.e., both, equilibrium constants are equal. However, this, is not always the case. For example in reaction, N2(g) + 3H2(g), 2NH3(g), , (p ), =, ( p )( p ), 2, , Kp, , NH 3, , 3, , N2, , H2, , Problem 7.3, , NH3 ( g ) [RT ], =, 3, 3, N 2 ( g ) RT . H 2 ( g ) ( RT ), 2, , 2, , PCl5, PCl3 and Cl2 are at equilibrium at, 500 K and having concentration 1.59M, PCl3, 1.59M Cl2 and 1.41 M PCl5., , 2021-22

Page 12 :

EQUILIBRIUM, , 203, , Calculate Kc for the reaction,, PCl5, , the value 0.194 should be neglected, because it will give concentration of the, reactant which is more than initial, concentration., Hence the equilibrium concentrations are,, [CO2] = [H2-] = x = 0.067 M, [CO] = [H2O] = 0.1 – 0.067 = 0.033 M, , PCl3 + Cl2, , Solution, The equilibrium constant Kc for the above, reaction can be written as,, , [PCl ] [Cl ] = (1.59), (1.41), [PCl ], , 2, , Kc =, , 3, , 2, , = 1.79, , 5, , Problem 7.5, For the equilibrium,, , Problem 7.4, The value of Kc = 4.24 at 800K for the reaction,, CO (g) + H2O (g), CO2 (g) + H2 (g), Calculate equilibrium concentrations of, CO2, H2, CO and H2O at 800 K, if only CO, and H 2 O are present initially at, concentrations of 0.10M each., Solution, For the reaction,, CO2 (g) + H2 (g), CO (g) + H2O (g), Initial concentration:, 0.1M, 0.1M, 0, 0, Let x mole per litre of each of the product, be formed., At equilibrium:, (0.1-x) M (0.1-x) M, xM, xM, where x is the amount of CO2 and H2 at, equilibrium., Hence, equilibrium constant can be, written as,, Kc = x2/(0.1-x)2 = 4.24, x2 = 4.24(0.01 + x2-0.2x), x2 = 0.0424 + 4.24x2-0.848x, 3.24x2 – 0.848x + 0.0424 = 0, a = 3.24, b = – 0.848, c = 0.0424, (for quadratic equation ax2 + bx + c = 0,, , (− b ±, x=, , b2 − 4ac, , ), , 2a, x = 0.848±√(0.848)2– 4(3.24)(0.0424)/, (3.24×2), x = (0.848 ± 0.4118)/ 6.48, x1 = (0.848 – 0.4118)/6.48 = 0.067, x2 = (0.848 + 0.4118)/6.48 = 0.194, , 2NO(g) + Cl2(g), 2NOCl(g), the value of the equilibrium constant, Kc, is 3.75 × 10–6 at 1069 K. Calculate the Kp, for the reaction at this temperature?, Solution, We know that,, ∆n, Kp = Kc(RT), For the above reaction,, ∆n = (2+1) – 2 = 1, Kp = 3.75 ×10–6 (0.0831 × 1069), Kp = 0.033, 7.5 HETEROGENEOUS EQUILIBRIA, Equilibrium in a system having more than one, phase is called heterogeneous equilibrium., The equilibrium between water vapour and, liquid water in a closed container is an, example of heterogeneous equilibrium., H2O(g), H2O(l), In this example, there is a gas phase and a, liquid phase. In the same way, equilibrium, between a solid and its saturated solution,, Ca(OH)2 (s) + (aq), Ca2+ (aq) + 2OH–(aq), is a heterogeneous equilibrium., Heterogeneous equilibria often involve pure, solids or liquids. We can simplify equilibrium, expressions for the heterogeneous equilibria, involving a pure liquid or a pure solid, as the, molar concentration of a pure solid or liquid, is constant (i.e., independent of the amount, present). In other words if a substance ‘X’ is, involved, then [X(s)] and [X(l)] are constant,, whatever the amount of ‘X’ is taken. Contrary, , 2021-22

Page 13 :

204, , CHEMISTRY, , to this, [X(g)] and [X(aq)] will vary as the, amount of X in a given volume varies. Let us, take thermal dissociation of calcium carbonate, which is an interesting and important example, of heterogeneous chemical equilibrium., CaCO3 (s), , CaO (s) + CO2 (g), , (7.16), , On the basis of the stoichiometric equation,, we can write,, , CaO ( s) CO2 ( g ), Kc =, CaCO 3 ( s), , 2, , Kp = PCO2 = 2 × 105 Pa/105 Pa = 2.00, Similarly, in the equilibrium between, nickel, carbon monoxide and nickel carbonyl, (used in the purification of nickel),, , Since [CaCO3(s)] and [CaO(s)] are both, constant, therefore modified equilibrium, constant for the thermal decomposition of, calcium carbonate will be, K´c = [CO2(g)], or Kp = pCO, , This shows that at a particular, temperature, there is a constant concentration, or pressure of CO2 in equilibrium with CaO(s), and CaCO3(s). Experimentally it has been, found that at 1100 K, the pressure of CO2 in, equilibrium with CaCO3(s) and CaO(s), is, 2.0 ×105 Pa. Therefore, equilibrium constant, at 1100K for the above reaction is:, , (7.17), (7.18), , Units of Equilibrium Constant, The value of equilibrium constant Kc can, be calculated by substituting the, concentration terms in mol/L and for K p, partial pressure is substituted in Pa, kPa,, bar or atm. This results in units of, equilibrium constant based on molarity or, pressure, unless the exponents of both the, numerator and denominator are same., For the reactions,, H2(g) + I2(g), 2HI, Kc and Kp have no unit., , Ni(CO)4 (g),, Ni (s) + 4 CO (g), the equilibrium constant is written as, , Ni (CO)4 , Kc = , [CO]4, It must be remembered that for the, existence of heterogeneous equilibrium pure, solids or liquids must also be present, (however small the amount may be) at, equilibrium, but their concentrations or, partial pressures do not appear in the, expression of the equilibrium constant. In the, reaction,, 2AgNO3(aq) +H2O(l), Ag2O(s) + 2HNO3(aq), , Kc =, , [ AgNO ], [HNO ], , 2, , 3, , 2, , 3, , N2O4(g), 2NO2 (g), Kc has unit mol/L and, Kp has unit bar, , Problem 7.6, , Equilibrium constants can also be, expressed as dimensionless quantities if, the standard state of reactants and, products are specified. For a pure gas, the, standard state is 1bar. Therefore a pressure, of 4 bar in standard state can be expressed, as 4 bar/1 bar = 4, which is a, dimensionless number. Standard state (c0), for a solute is 1 molar solution and all, concentrations can be measured with, respect to it. The numerical value of, equilibrium constant depends on the, standard state chosen. Thus, in this, system both K p and Kc are dimensionless, quantities but have different numerical, values due to different standard states., , The value of Kp for the reaction,, CO2 (g) + C (s), 2CO (g), is 3.0 at 1000 K. If initially PCO = 0.48 bar, 2, and PCO = 0 bar and pure graphite is, present, calculate the equilibrium partial, pressures of CO and CO2., Solution, For the reaction,, let ‘x’ be the decrease in pressure of CO2,, then, CO2(g) + C(s), 2CO(g), Initial, pressure: 0.48 bar, 0, , 2021-22

Page 14 :

EQUILIBRIUM, , 205, , At equilibrium:, (0.48 – x)bar, , Kp =, , 5. The equilibrium constant K for a reaction, is related to the equilibrium constant of the, corresponding reaction, whose equation is, obtained by multiplying or dividing the, equation for the original reaction by a small, integer., Let us consider applications of equilibrium, constant to:, • predict the extent of a reaction on the basis, of its magnitude,, • predict the direction of the reaction, and, • calculate equilibrium concentrations., , 2x bar, , 2, CO, , p, pC O2, , Kp = (2x)2/(0.48 – x) = 3, 4x2 = 3(0.48 – x), 4x2 = 1.44 – x, 4x2 + 3x – 1.44 = 0, a = 4, b = 3, c = –1.44, , (−b ±, x=, , b2 − 4 ac, , ), , 2a, = [–3 ± √(3)2– 4(4)(–1.44)]/2 × 4, = (–3 ± 5.66)/8, = (–3 + 5.66)/ 8 (as value of x cannot be, negative hence we neglect that value), x = 2.66/8 = 0.33, The equilibrium partial pressures are,, pCO = 2x = 2 × 0.33 = 0.66 bar, 2, , pCO = 0.48 – x = 0.48 – 0.33 = 0.15 bar, 2, , 7.6 APPLICATIONS OF EQUILIBRIUM, CONSTANTS, Before considering the applications of, equilibrium constants, let us summarise the, important features of equilibrium constants as, follows:, 1. Expression for equilibrium constant is, applicable only when concentrations of the, reactants and products have attained, constant value at equilibrium state., 2. The value of equilibrium constant is, independent of initial concentrations of the, reactants and products., 3. Equilibrium constant is temperature, dependent having one unique value for a, particular reaction represented by a, balanced equation at a given temperature., 4. The equilibrium constant for the reverse, reaction is equal to the inverse of the, equilibrium constant for the forward, reaction., , 7.6.1 Predicting the Extent of a Reaction, The numerical value of the equilibrium, constant for a reaction indicates the extent of, the reaction. But it is important to note that, an equilibrium constant does not give any, information about the rate at which the, equilibrium is reached. The magnitude of Kc, or K p is directly proportional to the, concentrations of products (as these appear, in the numerator of equilibrium constant, expression) and inversely proportional to the, concentrations of the reactants (these appear, in the denominator). This implies that a high, value of K is suggestive of a high concentration, of products and vice-versa., We can make the following generalisations, concerning the composition of, equilibrium mixtures:, • If Kc > 103, products predominate over, reactants, i.e., if Kc is very large, the reaction, proceeds nearly to completion. Consider, the following examples:, (a) The reaction of H2 with O2 at 500 K has a, very large equilibrium c o n s t a n t ,, Kc = 2.4 × 1047., (b) H2(g) + Cl2(g), Kc = 4.0 × 1031., , 2HCl(g) at 300K has, , (c) H 2(g) + Br 2(g), Kc = 5.4 × 1018, , 2HBr (g) at 300 K,, , •, , 2021-22, , If Kc < 10–3, reactants predominate over, products, i.e., if Kc is very small, the reaction, proceeds rarely. Consider the following, examples:

Page 15 :

206, , CHEMISTRY, , (a) The decomposition of H2O into H2 and O2, at 500 K has a very small equilibrium, constant, Kc = 4.1 × 10 –48, (b) N2(g) + O2(g), 2NO(g),, at 298 K has Kc = 4.8 ×10 – 31., • If K c is in the range of 10 – 3 to 10 3 ,, appreciable concentrations of both, reactants and products are present., Consider the following examples:, (a) For reaction of H2 with I2 to give HI,, Kc = 57.0 at 700K., (b) Also, gas phase decomposition of N2O4 to, NO2 is another reaction with a value, of Kc = 4.64 × 10 –3 at 25°C which is neither, too small nor too large. Hence,, equilibrium mixtures contain appreciable, concentrations of both N2O4 and NO2., These generarlisations are illustrated in, Fig. 7.6, , Fig.7.6 Dependence of extent of reaction on Kc, , 7.6.2 Predicting the Direction of the, Reaction, The equilibrium constant helps in predicting, the direction in which a given reaction will, proceed at any stage. For this purpose, we, calculate the reaction quotient Q. The, reaction quotient, Q (Q c with molar, concentrations and QP with partial pressures), is defined in the same way as the equilibrium, constant Kc except that the concentrations in, Qc are not necessarily equilibrium values., For a general reaction:, cC+dD, (7.19), aA+bB, c, d, a, b, Qc = [C] [D] / [A] [B], (7.20), , If Qc = Kc, the reaction mixture is already, at equilibrium., Consider the gaseous reaction of H 2, with I2,, H2(g) + I2(g), 2HI(g); Kc = 57.0 at 700 K., Suppose we have molar concentrations, [H2]t=0.10M, [I2]t = 0.20 M and [HI]t = 0.40 M., (the subscript t on the concentration symbols, means that the concentrations were measured, at some arbitrary time t, not necessarily at, equilibrium)., Thus, the reaction quotient, Qc at this stage, of the reaction is given by,, Qc = [HI]t2 / [H2]t [I2]t = (0.40)2/ (0.10)×(0.20), = 8.0, Now, in this case, Qc (8.0) does not equal, Kc (57.0), so the mixture of H2(g), I2(g) and HI(g), is not at equilibrium; that is, more H2(g) and, I2(g) will react to form more HI(g) and their, concentrations will decrease till Qc = Kc., The reaction quotient, Q c is useful in, predicting the direction of reaction by, comparing the values of Qc and Kc., Thus, we can make the following, generalisations concerning the direction of the, reaction (Fig. 7.7) :, , Fig. 7.7 Predicting the direction of the reaction, , •, •, •, , Then,, If Qc > Kc, the reaction will proceed in the, direction of reactants (reverse reaction)., If Qc < Kc, the reaction will proceed in the, direction of the products (forward reaction)., , 2021-22, , If Qc < Kc, net reaction goes from left to right, If Qc > Kc, net reaction goes from right to, left., If Qc = Kc, no net reaction occurs., Problem 7.7, The value of Kc for the reaction, 2A, B + C is 2 × 10–3. At a given time,, the composition of reaction mixture is, [A] = [B] = [C] = 3 × 10–4 M. In which, direction the reaction will proceed?

Page 16 :

EQUILIBRIUM, , 207, , Solution, For the reaction the reaction quotient Qc, is given by,, Qc = [B][C]/ [A]2, as [A] = [B] = [C] = 3 × 10 –4M, Qc = (3 ×10 –4)(3 × 10 –4) / (3 ×10 –4)2 = 1, as Qc > Kc so the reaction will proceed in, the reverse direction., , The total pressure at equilbrium was, found to be 9.15 bar. Calculate Kc, Kp and, partial pressure at equilibrium., , 7.6.3 Calculating Equilibrium, Concentrations, In case of a problem in which we know the, initial concentrations but do not know any of, the equilibrium concentrations, the following, three steps shall be followed:, Step 1. Write the balanced equation for the, reaction., Step 2. Under the balanced equation, make a, table that lists for each substance involved in, the reaction:, (a) the initial concentration,, (b) the change in concentration on going to, equilibrium, and, (c) the equilibrium concentration., In constructing the table, define x as the, concentration (mol/L) of one of the substances, that reacts on going to equilibrium, then use, the stoichiometry of the reaction to determine, the concentrations of the other substances in, terms of x., Step 3. Substitute the equilibrium, concentrations into the equilibrium equation, for the reaction and solve for x. If you are to, solve a quadratic equation choose the, mathematical solution that makes chemical, sense., Step 4. Calculate the equilibrium, concentrations from the calculated value of x., Step 5. Check your results by substituting, them into the equilibrium equation., Problem 7.8, 13.8g of N2O4 was placed in a 1L reaction, vessel at 400K and allowed to attain, equilibrium, N 2O4 (g), , 2NO2 (g), , 2021-22, , Solution, We know pV = nRT, Total volume (V ) = 1 L, Molecular mass of N2O4 = 92 g, Number of moles = 13.8g/92 g = 0.15, of the gas (n), Gas constant (R) = 0.083 bar L mol–1K–1, Temperature (T ) = 400 K, pV = nRT, p × 1L = 0.15 mol × 0.083 bar L mol–1K–1, × 400 K, p = 4.98 bar, N2O4, 2NO2, Initial pressure: 4.98 bar, 0, At equilibrium: (4.98 – x) bar 2x bar, Hence,, ptotal at equilibrium = pN O + pNO, 2 4, 2, 9.15 = (4.98 – x) + 2x, 9.15 = 4.98 + x, x = 9.15 – 4.98 = 4.17 bar, Partial pressures at equilibrium are,, pN O = 4.98 – 4.17 = 0.81bar, 2 4, , pNO = 2x = 2 × 4.17 = 8.34 bar, 2, , (, , K p = p NO2, Kp, , ), , 2, , / p N 2O4, , = (8.34)2/0.81 = 85.87, ∆n, = Kc(RT), , 85.87 = Kc(0.083 × 400)1, Kc = 2.586 = 2.6, Problem 7.9, 3.00 mol of PCl5 kept in 1L closed reaction, vessel was allowed to attain equilibrium, at 380K. Calculate composition of the, mixture at equilibrium. Kc= 1.80, Solution, PCl5, PCl3 + Cl2, Initial, concentration: 3.0, 0, 0

Page 17 :

208, , CHEMISTRY, 0, , K = e–∆G /RT, (7.23), Hence, using the equation (7.23), the, reaction spontaneity can be interpreted in, terms of the value of ∆G0., 0, 0, • If ∆G < 0, then –∆G /RT is positive, and, >1, making K >1, which implies, a spontaneous reaction or the reaction, which proceeds in the forward direction to, such an extent that the products are, present predominantly., 0, 0, • If ∆G > 0, then –∆G /RT is negative, and, , Let x mol per litre of PCl5 be dissociated,, At equilibrium:, (3-x), x, x, Kc = [PCl3][Cl2]/[PCl5], 1.8 = x2/ (3 – x), x2 + 1.8x – 5.4 = 0, x = [–1.8 ± √(1.8)2 – 4(–5.4)]/2, x = [–1.8 ± √3.24 + 21.6]/2, x = [–1.8 ± 4.98]/2, x = [–1.8 + 4.98]/2 = 1.59, [PCl5] = 3.0 – x = 3 –1.59 = 1.41 M, [PCl3] = [Cl2] = x = 1.59 M, , < 1, that is , K < 1, which implies, , 7.7 RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN, EQUILIBRIUM CONSTANT K,, REACTION QUOTIENT Q AND, GIBBS ENERGY G, The value of Kc for a reaction does not depend, on the rate of the reaction. However, as you, have studied in Unit 6, it is directly related, to the thermodynamics of the reaction and, in particular, to the change in Gibbs energy,, ∆G. If,, • ∆G is negative, then the reaction is, spontaneous and proceeds in the forward, direction., • ∆G is positive, then reaction is considered, non-spontaneous. Instead, as reverse, reaction would have a negative ∆G, the, products of the forward reaction shall be, converted to the reactants., • ∆G is 0, reaction has achieved equilibrium;, at this point, there is no longer any free, energy left to drive the reaction., A mathematical expression of this, thermodynamic view of equilibrium can be, described by the following equation:, 0, ∆G = ∆G + RT lnQ, (7.21), 0, where, G is standard Gibbs energy., At equilibrium, when ∆G = 0 and Q = Kc,, the equation (7.21) becomes,, 0, ∆G = ∆G + RT ln K = 0, 0, ∆G = – RT lnK, (7.22), 0, lnK = – ∆G / RT, Taking antilog of both sides, we get,, , a non-spontaneous reaction or a reaction, which proceeds in the forward direction to, such a small degree that only a very minute, quantity of product is formed., Problem 7.10, 0, The value of ∆G for the phosphorylation, of glucose in glycolysis is 13.8 kJ/mol., Find the value of Kc at 298 K., Solution, 0, ∆G = 13.8 kJ/mol = 13.8 × 103J/mol, 0, Also, ∆G = – RT lnKc, Hence, ln Kc = –13.8 × 103J/mol, (8.314 J mol –1K –1 × 298 K), ln Kc = – 5.569, Kc = e–5.569, Kc = 3.81 × 10 –3, Problem 7.11, Hydrolysis of sucrose gives,, Glucose + Fructose, Sucrose + H2O, Equilibrium constant Kc for the reaction, 0, is 2 ×1013 at 300K. Calculate ∆G at, 300K., Solution, 0, ∆G = – RT lnKc, 0, ∆G = – 8.314J mol–1K–1×, 300K × ln(2×1013), 0, 4, ∆G = – 7.64 ×10 J mol–1, 7.8 FACTORS AFFECTING EQUILIBRIA, One of the principal goals of chemical synthesis, is to maximise the conversion of the reactants, , 2021-22

Page 18 :

EQUILIBRIUM, , 209, , to products while minimizing the expenditure, of energy. This implies maximum yield of, products at mild temperature and pressure, conditions. If it does not happen, then the, experimental conditions need to be adjusted., For example, in the Haber process for the, synthesis of ammonia from N2 and H2, the, choice of experimental conditions is of real, economic importance. Annual world, production of ammonia is about hundred, million tones, primarily for use as fertilizers., Equilibrium constant, Kc is independent of, initial concentrations. But if a system at, equilibrium is subjected to a change in the, concentration of one or more of the reacting, substances, then the system is no longer at, equilibrium; and net reaction takes place in, some direction until the system returns to, equilibrium once again. Similarly, a change in, temperature or pressure of the system may, also alter the equilibrium. In order to decide, what course the reaction adopts and make a, qualitative prediction about the effect of a, change in conditions on equilibrium we use, Le Chatelier’s principle. It states that a, change in any of the factors that, determine the equilibrium conditions of a, system will cause the system to change, in such a manner so as to reduce or to, counteract the effect of the change. This, is applicable to all physical and chemical, equilibria., , “When the concentration of any of the, reactants or products in a reaction at, equilibrium is changed, the composition, of the equilibrium mixture changes so as, to minimize the effect of concentration, changes”., Let us take the reaction,, H2(g) + I2(g), 2HI(g), If H2 is added to the reaction mixture at, equilibrium, then the equilibrium of the, reaction is disturbed. In order to restore it, the, reaction proceeds in a direction wherein H2 is, consumed, i.e., more of H2 and I2 react to form, HI and finally the equilibrium shifts in right, (forward) direction (Fig.7.8). This is in, accordance with the Le Chatelier’s principle, which implies that in case of addition of a, reactant/product, a new equilibrium will be, set up in which the concentration of the, reactant/product should be less than what it, was after the addition but more than what it, was in the original mixture., , We shall now be discussing factors which, can influence the equilibrium., 7.8.1 Effect of Concentration Change, In general, when equilibrium is disturbed by, the addition/removal of any reactant/, products, Le Chatelier’s principle predicts that:, • The concentration stress of an added, reactant/product is relieved by net reaction, in the direction that consumes the added, substance., • The concentration stress of a removed, reactant/product is relieved by net reaction, in the direction that replenishes the, removed substance., or in other words,, , Fig. 7.8, , Effect of addition of H2 on change of, concentration for the reactants and, products, in, the, reaction,, H2(g) + I2 (g), 2HI(g), , The same point can be explained in terms, of the reaction quotient, Qc,, 2, Qc = [HI] / [H2][I2], , 2021-22

Page 19 :

210, , CHEMISTRY, , Addition of hydrogen at equilibrium results, in value of Qc being less than Kc . Thus, in order, to attain equilibrium again reaction moves in, the forward direction. Similarly, we can say, that removal of a product also boosts the, forward reaction and increases the, concentration of the products and this has, great commercial application in cases of, reactions, where the product is a gas or a, volatile substance. In case of manufacture of, ammonia, ammonia is liquified and removed, from the reaction mixture so that reaction, keeps moving in forward direction. Similarly,, in the large scale production of CaO (used as, important building material) from CaCO3,, constant removal of CO2 from the kiln drives, the reaction to completion. It should be, remembered that continuous removal of a, product maintains Qc at a value less than Kc, and reaction continues to move in the forward, direction., Effect of Concentration – An experiment, This can be demonstrated by the following, reaction:, –, , 2+, , Fe3+(aq)+ SCN (aq), [Fe(SCN)] (aq), yellow, colourless, deep red, , (7.24), , (7.25), A reddish colour appears on adding two, drops of 0.002 M potassium thiocynate, solution to 1 mL of 0.2 M iron(III) nitrate, solution due to the formation of [Fe(SCN)]2+., The intensity of the red colour becomes, constant on attaining equilibrium. This, equilibrium can be shifted in either forward, or reverse directions depending on our choice, of adding a reactant or a product. The, equilibrium can be shifted in the opposite, direction by adding reagents that remove Fe3+, –, or SCN ions. For example, oxalic acid, (H2C2O4), reacts with Fe3+ ions to form the, stable complex ion [Fe(C 2 O 4) 3 ] 3 – , thus, decreasing the concentration of free Fe3+(aq)., In accordance with the Le Chatelier’s principle,, the concentration stress of removed Fe3+ is, relieved by dissociation of [Fe(SCN)] 2+ to, , replenish the Fe 3+ ions. Because the, concentration of [Fe(SCN)]2+ decreases, the, intensity of red colour decreases., Addition of aq. HgCl2 also decreases red, –, colour because Hg2+ reacts with SCN ions to, 2–, form stable complex ion [Hg(SCN)4] . Removal, –, of free SCN (aq) shifts the equilibrium in, equation (7.24) from right to left to replenish, –, SCN ions. Addition of potassium thiocyanate, on the other hand increases the colour, intensity of the solution as it shift the, equilibrium to right., 7.8.2 Effect of Pressure Change, A pressure change obtained by changing the, volume can affect the yield of products in case, of a gaseous reaction where the total number, of moles of gaseous reactants and total, number of moles of gaseous products are, different. In applying Le Chatelier’s principle, to a heterogeneous equilibrium the effect of, pressure changes on solids and liquids can, be ignored because the volume (and, concentration) of a solution/liquid is nearly, independent of pressure., Consider the reaction,, CH4(g) + H2O(g), CO(g) + 3H2(g), Here, 4 mol of gaseous reactants (CO + 3H2), become 2 mol of gaseous products (CH4 +, H2O). Suppose equilibrium mixture (for above, reaction) kept in a cylinder fitted with a piston, at constant temperature is compressed to one, half of its original volume. Then, total pressure, will, be, doubled, (according, to, pV = constant). The partial pressure and, therefore, concentration of reactants and, products have changed and the mixture is no, longer at equilibrium. The direction in which, the reaction goes to re-establish equilibrium, can be predicted by applying the Le Chatelier’s, principle. Since pressure has doubled, the, equilibrium now shifts in the forward, direction, a direction in which the number of, moles of the gas or pressure decreases (we, know pressure is proportional to moles of the, gas). This can also be understood by using, reaction quotient, Qc. Let [CO], [H2], [CH4] and, [H 2 O] be the molar concentrations at, equilibrium for methanation reaction. When, , 2021-22

Page 20 :

EQUILIBRIUM, , 211, , volume of the reaction mixture is halved, the, partial pressure and the concentration are, doubled. We obtain the reaction quotient by, replacing each equilibrium concentration by, double its value., , CH4 ( g ) H2 O ( g ), Qc = , 3, CO ( g ) H2 (g ), As Qc < Kc , the reaction proceeds in the, forward direction., In reaction C(s) + CO2(g), 2CO(g), when, pressure is increased, the reaction goes in the, reverse direction because the number of moles, of gas increases in the forward direction., 7.8.3 Effect of Inert Gas Addition, , �, , If the volume is kept constant and an inert gas, such as argon is added which does not take, part in the reaction, the equilibrium remains, undisturbed. It is because the addition of an, inert gas at constant volume does not change, the partial pressures or the molar, concentrations of the substance involved in the, reaction. The reaction quotient changes only, if the added gas is a reactant or product, involved in the reaction., 7.8.4 Effect of Temperature Change, Whenever an equilibrium is disturbed by a, change in the concentration, pressure or, volume, the composition of the equilibrium, mixture changes because the reaction, quotient, Qc no longer equals the equilibrium, constant, Kc. However, when a change in, temperature occurs, the value of equilibrium, constant, Kc is changed., , Production of ammonia according to the, reaction,, N2(g) + 3H2(g), 2NH3(g) ;, ∆H= – 92.38 kJ mol–1, is an exothermic process. According to, Le Chatelier’s principle, raising the, temperature shifts the equilibrium to left and, decreases the equilibrium concentration of, ammonia. In other words, low temperature is, favourable for high yield of ammonia, but, practically very low temperatures slow down, the reaction and thus a catalyst is used., Effect of Temperature – An experiment, Effect of temperature on equilibrium can be, demonstrated by taking NO2 gas (brown in, colour) which dimerises into N 2 O 4 gas, (colourless)., N2O4(g); ∆H = –57.2 kJ mol–1, 2NO2(g), NO 2 gas prepared by addition of Cu, turnings to conc. HNO3 is collected in two, 5 mL test tubes (ensuring same intensity of, colour of gas in each tube) and stopper sealed, with araldite. Three 250 mL beakers 1, 2 and, 3 containing freezing mixture, water at room, temperature and hot water (363 K ),, respectively, are taken (Fig. 7.9). Both the test, tubes are placed in beaker 2 for 8-10 minutes., After this one is placed in beaker 1 and the, other in beaker 3. The effect of temperature, on direction of reaction is depicted very well, in this experiment. At low temperatures in, beaker 1, the forward reaction of formation of, N2O4 is preferred, as reaction is exothermic, and, thus, intensity of brown colour due to NO2, decreases. While in beaker 3, high, temperature favours the reverse reaction of, , In general, the temperature dependence of, the equilibrium constant depends on the sign, of ∆H for the reaction., •, , The equilibrium constant for an exothermic, reaction (negative ∆H) decreases as the, temperature increases., , •, , The equilibrium constant for an, endothermic reaction (positive ∆H), increases as the temperature increases., , Temperature changes affect the, equilibrium constant and rates of reactions., , Fig. 7.9 Effect of temperature on equilibrium for, the reaction, 2NO2 (g), N2O4 (g), , 2021-22

Page 21 :

212, , CHEMISTRY, , formation of NO2 and thus, the brown colour, intensifies., Effect of temperature can also be seen in, an endothermic reaction,, 3+, , –, , [Co(H2O) 6] (aq) + 4Cl (aq), pink, , colourless, , 2–, , [CoCl4] (aq) +, 6H2O(l), blue, , At room temperature, the equilibrium, mixture is blue due to [CoCl4]2–. When cooled, in a freezing mixture, the colour of the mixture, turns pink due to [Co(H2O)6]3+., 7.8.5 Effect of a Catalyst, A catalyst increases the rate of the chemical, reaction by making available a new low energy, pathway for the conversion of reactants to, products. It increases the rate of forward and, reverse reactions that pass through the same, transition state and does not affect, equilibrium. Catalyst lowers the activation, energy for the forward and reverse reactions, by exactly the same amount. Catalyst does not, affect the equilibrium composition of a, reaction mixture. It does not appear in the, balanced chemical equation or in the, equilibrium constant expression., Let us consider the formation of NH3 from, dinitrogen and dihydrogen which is highly, exothermic reaction and proceeds with, decrease in total number of moles formed as, compared to the reactants. Equilibrium, constant decreases with increase in, temperature. At low temperature rate, decreases and it takes long time to reach at, equilibrium, whereas high temperatures give, satisfactory rates but poor yields., German chemist, Fritz Haber discovered, that a catalyst consisting of iron catalyse the, reaction to occur at a satisfactory rate at, temperatures, where the equilibrium, concentration of NH3 is reasonably favourable., Since the number of moles formed in the, reaction is less than those of reactants, the, yield of NH3 can be improved by increasing, the pressure., Optimum conditions of temperature and, pressure for the synthesis of NH 3 using, catalyst are around 500 °C and 200 atm., , Similarly, in manufacture of sulphuric, acid by contact process,, 2SO2(g) + O2(g), , 2SO3(g); Kc = 1.7 × 1026, , though the value of K is suggestive of reaction, going to completion, but practically the oxidation, of SO2 to SO3 is very slow. Thus, platinum or, divanadium penta-oxide (V2O5) is used as, catalyst to increase the rate of the reaction., Note: If a reaction has an exceedingly small, K, a catalyst would be of little help., 7.9 IONIC EQUILIBRIUM IN SOLUTION, Under the effect of change of concentration on, the direction of equilibrium, you have, incidently come across with the following, equilibrium which involves ions:, Fe3+(aq) + SCN–(aq), , [Fe(SCN)]2+(aq), , There are numerous equilibria that involve, ions only. In the following sections we will, study the equilibria involving ions. It is well, known that the aqueous solution of sugar, does not conduct electricity. However, when, common salt (sodium chloride) is added to, water it conducts electricity. Also, the, conductance of electricity increases with an, increase in concentration of common salt., Michael Faraday classified the substances into, two categories based on their ability to conduct, electricity. One category of substances, conduct electricity in their aqueous solutions, and are called electrolytes while the other do, not and are thus, referred to as nonelectrolytes. Faraday further classified, electrolytes into strong and weak electrolytes., Strong electrolytes on dissolution in water are, ionized almost completely, while the weak, electrolytes are only partially dissociated., For example, an aqueous solution of, sodium chloride is comprised entirely of, sodium ions and chloride ions, while that, of acetic acid mainly contains unionized, acetic acid molecules and only some acetate, ions and hydronium ions. This is because, there is almost 100% ionization in case of, sodium chloride as compared to less, than 5% ionization of acetic acid which is, a weak electrolyte. It should be noted, that in weak electrolytes, equilibrium is, , 2021-22

Page 22 :

EQUILIBRIUM, , 213, , established between ions and the unionized, molecules. This type of equilibrium involving, ions in aqueous solution is called ionic, equilibrium. Acids, bases and salts come, under the category of electrolytes and may act, as either strong or weak electrolytes., 7.10, , ACIDS, BASES AND SALTS, , Acids, bases and salts find widespread, occurrence in nature. Hydrochloric acid, present in the gastric juice is secreted by the, lining of our stomach in a significant amount, of 1.2-1.5 L/day and is essential for digestive, processes. Acetic acid is known to be the main, constituent of vinegar. Lemon and orange, juices contain citric and ascorbic acids, and, tartaric acid is found in tamarind paste. As, most of the acids taste sour, the word “acid”, has been derived from a latin word “acidus”, meaning sour. Acids are known to turn blue, litmus paper into red and liberate dihydrogen, on reacting with some metals. Similarly, bases, are known to turn red litmus paper blue, taste, bitter and feel soapy. A common example of a, base is washing soda used for washing, purposes. When acids and bases are mixed in, the right proportion they react with each other, to give salts. Some commonly known, examples of salts are sodium chloride, barium, sulphate, sodium nitrate. Sodium chloride, (common salt ) is an important component of, our diet and is formed by reaction between, hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide. It, , exists in solid state as a cluster of positively, charged sodium ions and negatively charged, chloride ions which are held together due to, electrostatic interactions between oppositely, charged species (Fig.7.10). The electrostatic, forces between two charges are inversely, proportional to dielectric constant of the, medium. Water, a universal solvent, possesses, a very high dielectric constant of 80. Thus,, when sodium chloride is dissolved in water,, the electrostatic interactions are reduced by a, factor of 80 and this facilitates the ions to move, freely in the solution. Also, they are wellseparated due to hydration with water, molecules., , Fig.7.10 Dissolution of sodium chloride in water., Na+ and Cl – ions are stablised by their, hydration with polar water molecules., , Comparing, the ionization of hydrochloric, acid with that of acetic acid in water we find, that though both of them are polar covalent, , Faraday was born near London into a family of very limited means. At the age of 14 he, was an apprentice to a kind bookbinder who allowed Faraday to read the books he, was binding. Through a fortunate chance he became laboratory assistant to Davy, and, during 1813-4, Faraday accompanied him to the Continent. During this trip he gained, much from the experience of coming into contact with many of the leading scientists of, the time. In 1825, he succeeded Davy as Director of the Royal Institution laboratories,, and in 1833 he also became the first Fullerian Professor of Chemistry. Faraday’s first Michael Faraday, (1791–1867), important work was on analytical chemistry. After 1821 much of his work was on, electricity and magnetism and different electromagnetic phenomena. His ideas have led to the establishment, of modern field theory. He discovered his two laws of electrolysis in 1834. Faraday was a very modest, and kind hearted person. He declined all honours and avoided scientific controversies. He preferred to, work alone and never had any assistant. He disseminated science in a variety of ways including his, Friday evening discourses, which he founded at the Royal Institution. He has been very famous for his, Christmas lecture on the ‘Chemical History of a Candle’. He published nearly 450 scientific papers., , 2021-22

Page 23 :

214, , CHEMISTRY, , molecules, former is completely ionized into, its constituent ions, while the latter is only, partially ionized (< 5%). The extent to which, ionization occurs depends upon the strength, of the bond and the extent of solvation of ions, produced. The terms dissociation and, ionization have earlier been used with different, meaning. Dissociation refers to the process of, separation of ions in water already existing as, such in the solid state of the solute, as in, sodium chloride. On the other hand, ionization, corresponds to a process in which a neutral, molecule splits into charged ions in the, solution. Here, we shall not distinguish, between the two and use the two terms, interchangeably., , Hydronium and Hydroxyl Ions, Hydrogen ion by itself is a bare proton with, very small size (~10 –15 m radius) and, intense electric field, binds itself with the, water molecule at one of the two available, +, lone pairs on it giving H3O . This species, has been detected in many compounds, +, –, (e.g., H3O Cl ) in the solid state. In aqueous, solution the hydronium ion is further, +, +, hydrated to give species like H5O2 , H7O3 and, +, H9O4 . Similarly the hydroxyl ion is hydrated, –, –, to give several ionic species like H3O2 , H5O3, –, and H7O4 etc., , 7.10.1 Arrhenius Concept of Acids and, Bases, According to Arrhenius theory, acids are, substances that dissociates in water to give, +, hydrogen ions H (aq) and bases are, substances that produce hydroxyl ions, –, OH (aq). The ionization of an acid HX (aq) can, be represented by the following equations:, HX (aq) → H (aq) + X (aq), or, +, –, HX(aq) + H2O(l) → H3O (aq) + X (aq), +, , –, , A bare proton, H+ is very reactive and, cannot exist freely in aqueous solutions. Thus,, it bonds to the oxygen atom of a solvent water, molecule to give trigonal pyramidal, +, +, hydronium ion, H3O {[H (H2O)] } (see box)., +, +, In this chapter we shall use H (aq) and H3O (aq), interchangeably to mean the same i.e., a, hydrated proton., , +, , H9O4, , 7.10.2 The Brönsted-Lowry Acids and, Bases, The Danish chemist, Johannes Brönsted and, the English chemist, Thomas M. Lowry gave a, more general definition of acids and bases., According to Brönsted-Lowry theory, acid is, a substance that is capable of donating a, hydrogen ion H+ and bases are substances, capable of accepting a hydrogen ion, H+. In, short, acids are proton donors and bases are, proton acceptors., Consider the example of dissolution of NH3, in H2O represented by the following equation:, , Similarly, a base molecule like MOH, ionizes in aqueous solution according to the, equation:, MOH(aq) → M (aq) + OH (aq), The hydroxyl ion also exists in the hydrated, form in the aqueous solution. Arrhenius, concept of acid and base, however, suffers, from the limitation of being applicable only to, aqueous solutions and also, does not account, for the basicity of substances like, ammonia, which do not possess a hydroxyl group., +, , –, , The basic solution is formed due to the, presence of hydroxyl ions. In this reaction,, water molecule acts as proton donor and, ammonia molecule acts as proton acceptor, and are thus, called Lowry-Brönsted acid and, , 2021-22

Page 24 :

EQUILIBRIUM, , 215, , Arrhenius was born near Uppsala, Sweden. He presented his thesis, on the conductivities, of electrolyte solutions, to the University of Uppsala in 1884. For the next five years he, travelled extensively and visited a number of research centers in Europe. In 1895 he was, appointed professor of physics at the newly formed University of Stockholm, serving its, rector from 1897 to 1902. From 1905 until his death he was Director of physical chemistry, at the Nobel Institute in Stockholm. He continued to work for many years on electrolytic, solutions. In 1899 he discussed the temperature dependence of reaction rates on the, basis of an equation, now usually known as Arrhenius equation., He worked in a variety of fields, and made important contributions to, immunochemistry, cosmology, the origin of life, and the causes of ice age. He was the, Svante Arrhenius, first to discuss the ‘green house effect’ calling by that name. He received Nobel Prize in, (1859-1927), Chemistry in 1903 for his theory of electrolytic dissociation and its use in the development, of chemistry., , base, respectively. In the reverse reaction, H+, is transferred from NH4+ to OH – . In this case,, –, NH4+ acts as a Bronsted acid while OH acted, as a Brönsted base. The acid-base pair that, differs only by one proton is called a conjugate, –, acid-base pair. Therefore, OH is called the, +, conjugate base of an acid H2O and NH4 is, called conjugate acid of the base NH 3. If, Brönsted acid is a strong acid then its, conjugate base is a weak base and viceversa. It may be noted that conjugate acid, has one extra proton and each conjugate base, has one less proton., Consider the example of ionization of, hydrochloric acid in water. HCl(aq) acts as an, acid by donating a proton to H2O molecule, which acts as a base., , ammonia it acts as an acid by donating a, proton., , It can be seen in the above equation, that, water acts as a base because it accepts the, proton. The species H3O+ is produced when, water accepts a proton from HCl. Therefore,, –, Cl is a conjugate base of HCl and HCl is the, –, conjugate acid of base Cl . Similarly, H2O is a, +, +, conjugate base of an acid H3O and H3O is a, conjugate acid of base H2O., It is interesting to observe the dual role of, water as an acid and a base. In case of reaction, with HCl water acts as a base while in case of, , 2021-22, , Problem 7.12, What will be the conjugate bases for the, following Brönsted acids: HF, H2SO4 and, –, HCO3 ?, Solution, The conjugate bases should have one, proton less in each case and therefore the, –, corresponding conjugate bases are: F ,, –, 2–, HSO4 and CO3 respectively., Problem 7.13, Write the conjugate acids for the following, –, –, Brönsted bases: NH2 , NH3 and HCOO ., Solution, The conjugate acid should have one extra, proton in each case and therefore the, corresponding conjugate acids are: NH3,, +, NH4 and HCOOH respectively., Problem 7.14, –, –, The species: H2O, HCO3 , HSO4 and NH3, can act both as Bronsted acids and bases., For each case give the corresponding, conjugate acid and conjugate base., Solution, The answer is given in the following Table:, Species Conjugate, Conjugate, acid, base, –, +, H2O, H3O, OH, –, HCO3, H2CO3, CO32–, –, HSO4, H2SO4, SO42–, –, NH3, NH4+, NH2

Page 25 :

216, , CHEMISTRY, , 7.10.3 Lewis Acids and Bases, G.N. Lewis in 1923 defined an acid as a, species which accepts electron pair and base, which donates an electron pair. As far as, bases are concerned, there is not much, difference between Brönsted-Lowry and Lewis, concepts, as the base provides a lone pair in, both the cases. However, in Lewis concept, many acids do not have proton. A typical, example is reaction of electron deficient species, BF3 with NH3., BF3 does not have a proton but still acts, as an acid and reacts with NH3 by accepting, its lone pair of electrons. The reaction can be, represented by,, BF3 + :NH3 → BF3:NH3, Electron deficient species like AlCl3, Co3+,, Mg , etc. can act as Lewis acids while species, –, like H2O, NH3, OH etc. which can donate a pair, of electrons, can act as Lewis bases., 2+, , Problem 7.15, Classify the following species into Lewis, acids and Lewis bases and show how, these act as such:, –, –, +, (a) HO (b)F, (c) H, (d) BCl3, Solution, (a) Hydroxyl ion is a Lewis base as it can, –, donate an electron lone pair (:OH )., (b) Flouride ion acts as a Lewis base as, it can donate any one of its four, electron lone pairs., (c) A proton is a Lewis acid as it can, accept a lone pair of electrons from, bases like hydroxyl ion and fluoride, ion., (d) BCl3 acts as a Lewis acid as it can, accept a lone pair of electrons from, species like ammonia or amine, molecules., 7.11 IONIZATION OF ACIDS AND BASES, Arrhenius concept of acids and bases becomes, useful in case of ionization of acids and bases, as mostly ionizations in chemical and, biological systems occur in aqueous medium., Strong acids like perchloric acid (HClO4),, , hydrochloric acid (HCl), hydrobromic acid, (HBr), hyrdoiodic acid (HI), nitric acid (HNO3), and sulphuric acid (H2SO4) are termed strong, because they are almost completely, dissociated into their constituent ions in an, aqueous medium, thereby acting as proton, (H +) donors. Similarly, strong bases like, lithium hydroxide (LiOH), sodium hydroxide, (NaOH), potassium hydroxide (KOH), caesium, hydroxide (CsOH) and barium hydroxide, Ba(OH)2 are almost completely dissociated into, ions in an aqueous medium giving hydroxyl, ions, OH – . According to Arrhenius concept, they are strong acids and bases as they are, +, able to completely dissociate and produce H3O, –, and OH ions respectively in the medium., Alternatively, the strength of an acid or base, may also be gauged in terms of BrönstedLowry concept of acids and bases, wherein a, strong acid means a good proton donor and a, strong base implies a good proton acceptor., Consider, the acid-base dissociation, equilibrium of a weak acid HA,, HA(aq) + H2O(l), H3O+(aq) + A–(aq), conjugate conjugate, acid, base, acid, base, In section 7.10.2 we saw that acid (or base), dissociation equilibrium is dynamic involving, a transfer of proton in forward and reverse, directions. Now, the question arises that if the, equilibrium is dynamic then with passage of, time which direction is favoured? What is the, driving force behind it? In order to answer, these questions we shall deal into the issue of, comparing the strengths of the two acids (or, bases) involved in the dissociation equilibrium., Consider the two acids HA and H3O+ present, in the above mentioned acid-dissociation, equilibrium. We have to see which amongst, them is a stronger proton donor. Whichever, exceeds in its tendency of donating a proton, over the other shall be termed as the stronger, acid and the equilibrium will shift in the, direction of weaker acid. Say, if HA is a, stronger acid than H3O+, then HA will donate, protons and not H3O+, and the solution will, mainly contain A – and H 3 O + ions. The, equilibrium moves in the direction of, formation of weaker acid and weaker base, , 2021-22

Page 26 :