Page 1 :

The Cell Cycle and Its Regulation, Introduction, The cell cycle is an ordered series of events involving cell growth and, cell division that produces two new daughter cells from one parent, cell. Cells on the path to cell division proceed through a series of, precisely timed and carefully regulated stages of growth, DNA, replication, and nuclear and cytoplasmic division that ultimately, produces two identical (clone) cells., The process of cell division is complex and highly regulated, (regulation is discussed in the latter half of this chapter). To begin, we, will explore the stages of the cell cycle:, Interphase, , The cell cycle has two major phases: interphase and the mitotic phase., During interphase, the cell grows, and DNA is replicated. During the, mitotic phase, the replicated DNA and cytoplasmic contents are, separated, and the cell cytoplasm is typically partitioned by a third, process of the cell cycle called cytokinesis (Figure 13-1)., During interphase, the cell undergoes normal growth processes while, also preparing for cell division. For a cell to move from interphase, into the mitotic phase, many internal and external conditions must be, met. The three stages of interphase are called G1, S, and G2.

Page 2 :

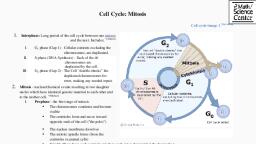

Figure 13-1: The eukaryotic cell cycle. The cell cycle in, multicellular organisms consists of interphase and the mitotic phase., During interphase, the cell grows and the nuclear DNA is duplicated., Interphase is followed by the mitotic phase. During the mitotic phase,, the duplicated chromosomes are segregated and distributed into, daughter nuclei. Following mitosis, the cytoplasm is usually divided, as well by cytokinesis, resulting in two genetically identical daughter, cells., G1 Phase (First Gap), The first stage of interphase is called the G1 phase (first gap) because,, from a microscopic point of view, little change is visible. However,, during the G1 stage, the cell is quite active at the biochemical level., The cell is accumulating the building blocks of chromosomal DNA, and the associated proteins as well as accumulating sufficient energy

Page 3 :

reserves to complete the task of replicating each chromosome in the, nucleus. Furthermore, during the G1 stage, DNA is assessed for, damage and repaired, if needed, and the cell also grows in size., S Phase (Synthesis of DNA), Throughout interphase, nuclear DNA remains in a semi-condensed, chromatin configuration. In the S phase, DNA replication can proceed, through the mechanisms that result in the formation of identical pairs, of DNA molecules—sister chromatids—that are firmly attached to the, centromeric region. Proteins called cohesins loop around sister, chromatids to keep them connected. The centrosome is also duplicated, during the S phase. The two centrosomes of homologous, chromosomes will give rise to the mitotic spindle, the apparatus that, orchestrates the movement of chromosomes during mitosis. For, example, the centrosomes are associated with a pair of rod-like, objects, the centrioles, which are positioned at right angles to each, other. Centrioles help organize cell division., G2 Phase (Second Gap), In the G2 phase, the cell replenishes its energy stores and synthesizes, proteins necessary for chromosome manipulation and movement., Some cell organelles are duplicated, and the cytoskeleton is, dismantled to provide resources for the mitotic phase. As in the, G1 stage, during G2, the size of the cell increases and DNA damaged is, repaired, if needed. The final preparations for the mitotic phase must, be completed before the cell can enter the first stage of mitosis., M-Phase, , The mitotic phase (M-phase) is a multistep process during which the, duplicated chromosomes are aligned, separated, and move into two, new, identical daughter cells. M-phase has several sub-phases:, prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and cytokinesis, (Figure 13-2).

Page 4 :

Figure 13-2: Sub-phases of Mitosis. Mitosis is divided into five, stages—prophase, prometaphase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase., The pictures at the bottom were taken by fluorescence microscopy, (hence, the black background) of cells artificially stained by, fluorescent dyes: blue fluorescence indicates DNA (chromosomes), and green fluorescence indicates microtubules (spindle apparatus)., Prophase, During prophase, the “first phase,” several events must occur to, provide access to the chromosomes in the nucleus. The nuclear, envelope starts to break down. This is caused by phosphorylation of, nuclear pore proteins and lamins, the intermediate filament, cytoskeletal protein that provides structure to the nuclear envelope, by

Page 5 :

the cell cycle regulatory protein M-cyclin/Cdk (cyclins and Cdks are, discussed in more detail later in the chapter). Later, in telophase, these, proteins will be dephosphorylated to reform the nuclear envelope, (Figure 13-3)., , Figure 13-3: The breakdown and reformation of the nuclear, envelope. During late prophase (prometaphase), lamins and nuclear, pore proteins are phosphorylated. This causes the nuclear envelope to, break down. In telophase, the nuclear envelope is reformed. This, occurs when lamins and nuclear pore proteins are dephosphorylated,, causing them to reassemble., Additionally, the Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum fragment, and disperse to the periphery of the cell. The nucleolus disappears, and, centrosomes begin to move to opposite poles of the cell. The

Page 6 :

microtubules that form the mitotic spindle extend between the, centrosomes, pushing them farther apart as the microtubule fibers, lengthen, due to dynamic instability. The sister chromatids begin to, coil more tightly and become visible under a light microscope. This, process is facilitated by proteins called condensins, ring-shaped, proteins that further condense chromatin. Condensins are, phosphorylated by M-cyclin/Cdk to further condense chromatin., During the latter part of prophase (sometimes termed prometaphase),, many processes that were begun in prophase continue to advance and, culminate in the formation of a connection between the chromosomes, and cytoskeleton. The remnants of the nuclear envelope disappear., The mitotic spindle continues to develop as more microtubules, assemble and stretch across the length of the former nuclear area., Chromosomes become more condensed and visually discrete. Each, sister chromatid attaches to spindle microtubules at the centromere via, a protein complex called the kinetochore., Metaphase, During metaphase, all of the chromosomes are aligned on the, metaphase plate, or the equatorial plane, midway between the two, poles of the cell. The sister chromatids are still tightly attached to each, other, and the chromosomes are maximally condensed., Anaphase, During anaphase, the sister chromatids at the equatorial plane are, held together by cohesins. Before the chromatids can be separated, the, cohesins must be removed. This is regulated by a protein, called Anaphase Promoting Complex (APC). Prior to anaphase,, APC is in its inactive (dephosphorylated) state. At the beginning of, anaphase, APC is phosphorylated by M-cyclin/Cdk and becomes, active. APC is a ubiquitin ligase, meaning it can add a small peptide, called ubiquitin to proteins. When ubiquitin ligases add certain

Page 8 :

non-kinetochore microtubules slide against each other at the, metaphase plate where they overlap., Telophase, During telophase, all of the events that set up the duplicated, chromosomes for mitosis during the first three phases are reversed., The chromosomes reach the opposite poles and begin to decondense, (unravel). The mitotic spindles are broken down into monomers that, will be used to assemble cytoskeleton components for each daughter, cell. As previously mentioned, lamins and nuclear pore proteins are, dephosphorylated, leading to the reformation of the nuclear envelope, chromosomes., Cytokinesis, Cytokinesis is the second part of the mitotic phase during which cell, division is completed by the physical separation of the cytoplasmic, components into two daughter cells. Although the stages of mitosis are, similar for most eukaryotes, the process of cytokinesis is quite, different for eukaryotes that have cell walls, such as plant cells., In animal cells, cytokinesis begins following the onset of anaphase., A contractile ring composed of actin filaments forms just inside the, plasma membrane at the former metaphase plate. The actin filaments, pull the equator of the cell inward, forming a fissure. This fissure, or, “crack,” is called the cleavage furrow. The furrow deepens as the, actin ring contracts, and eventually, the membrane and cell are, cleaved in two (Figure 13-5).

Page 9 :

Figure 13-5: Cytokinesis. In the upper panel, a cleavage furrow, forms at the former metaphase plate in the animal cell. The plasma, membrane is drawn in by a ring of actin fibers contracting just inside, the membrane. The cleavage furrow deepens until the cells are, pinched in two., G0 Phase, , As mentioned in the introduction, not all cells adhere to the classic, cell-cycle pattern in which a newly formed daughter cell immediately, enters interphase, closely followed by the mitotic phase. Cells in the, G0 phase are not actively preparing to divide. The cell is in a quiescent, (inactive) stage, having exited the cell cycle. Some cells enter, G0 temporarily until an external signal triggers the onset of G1. Other, cells that never or rarely divide, such as mature cardiac muscle and, nerve cells, remain in G0 permanently., The cell cycle is shown in a circular graphic, with four stages., Interphase accounts for the most time spent in the cell cycle with the, G1 stage accounting for approximately 39% of the cycle, the S stage, for about 40%, and the G2 phase for about 19%. Mitosis only accounts, for approximately 2% of the cell cycle, thus demonstrating the, importance of the preparation steps in interphase over the division in

Page 10 :

mitosis. An arrow is shown exiting the G1 stage that points to the, G0 stage outside the circle, in which cells are not actively dividing., Another arrow points from the G0 stage back into the G1 stage, where, cells may re-enter the cycle (Figure 13-6)., , Figure 13-6: G0 Phase. Cells that are not actively preparing to divide, enter an alternate phase called G0. In some cases, this is a temporary, condition until triggered to enter G1. In other cases, the cell will, remain in G0 permanently., , Control of the Cell Cycle, The length of the cell cycle is highly variable even within the cells of, an individual organism. In humans, the frequency of cell turnover, ranges from a few hours in early embryonic development to an

Page 11 :

average of two to five days for epithelial cells or an entire human, lifetime spent in G0 by specialized cells such as cortical neurons or, cardiac muscle cells. There is also variation in the time that a cell, spends in each phase of the cell cycle. When fast-dividing mammalian, cells are grown in culture (outside the body under optimal growing, conditions), the length of the cycle is approximately 24 hours. The, timing of events in the cell cycle is controlled by mechanisms that are, both internal and external to the cell., Regulation at Internal Checkpoints, , Daughter cells must be exact duplicates of the parent cell. Mistakes in, the duplication or distribution of the chromosomes can lead to, mutations that may be passed forward to every new cell produced, from the abnormal cell. To prevent a compromised cell from, continuing to divide, there are internal control mechanisms that, operate at three main cell cycle checkpoints (Figure. 13-7). The cell, cycle can be stopped until conditions are favorable or errors have been, corrected. These checkpoints occur at the end of G1 (G1-S checkpoint),, at the end of G2 (G2–M checkpoint), and during metaphase (M, checkpoint).

Page 12 :

Figure 13-7: Cell Cycle Checkpoints. The cell cycle is controlled at, three checkpoints. The integrity of the DNA is assessed at the G1-S, checkpoint. Proper chromosome duplication is assessed at the G2-M, checkpoint. Attachment of each kinetochore to a spindle fiber is, assessed at the M checkpoint., The G1-S Checkpoint, The G1-S checkpoint determines whether all conditions are favorable, for cell division to proceed and for DNA replication to occur during S, phase. The G1-S checkpoint, also called the restriction point, is the, point at which the cell irreversibly commits to the cell division, process. In addition to adequate reserves and cell size, there is a check, for damage to the genomic DNA and ensure there is space for a near

Page 13 :

cell at the G1-S checkpoint. A cell that does not meet all the, requirements will “arrest” (pause or become quiescent) in G1 and will, attempt to correct these deficiencies (e.g., repair DNA damage). If,, during cell cycle arrest, the cell can meet the G1-S checkpoint criteria,, the cell cycle will proceed to the S phase. If not, the cell will undergo, apoptosis (programmed cell death) (See Chapter 15)., The G2-M Checkpoint, The G2-M checkpoint bars the entry to the mitotic phase if certain, conditions are not met. As in the G1-S checkpoint, cell size and protein, reserves are assessed. However, the most important role of the, G2 checkpoint is to ensure that all of the chromosomes have been, replicated and that the replicated DNA is not damaged. Also similar to, the G1-S checkpoint, the cell cycle will arrest at the G2-M transition if, checkpoint criteria are not met and will attempt to repair the damage, or undergo apoptosis if damaged severely., The M Checkpoint, The M checkpoint occurs near the end of the metaphase stage of, mitosis. The M checkpoint is also known as the spindle checkpoint, because it determines if all the sister chromatids are correctly attached, to the spindle microtubules. Because the separation of the sister, chromatids during anaphase is an irreversible step, the cycle will not, proceed until the kinetochores of each pair of sister chromatids are, firmly anchored to spindle fibers arising from opposite poles of the, cell. As with the previous checkpoints, cells that cannot proceed past, this checkpoint will be eliminated by apoptosis., Regulator Molecules of the Cell Cycle, , In addition to the internally controlled checkpoints, two groups of, intracellular molecules regulate the cell cycle. These regulatory, molecules either promote the progress of the cell to the next phase, (positive regulation) or halt the cycle (negative regulation). Regulator

Page 14 :

molecules may act individually, or they can influence the activity or, production of other regulatory proteins. Therefore, the failure of a, single regulator may have almost no effect on the cell cycle, especially, if more than one mechanism controls the same event. However, the, impact of a deficient or non-functioning regulator can be wide-ranging, and possibly fatal to the cell if multiple processes are affected., Positive Regulation of the Cell Cycle, Two groups of proteins, called cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases, (Cdks), are termed, positive regulators. They are responsible for the, progress of the cell through the various checkpoints. The levels, of cyclin proteins fluctuate throughout the cell cycle in a predictable, pattern (This is the origin of their name. Cyclin levels “cycle” up and, down throughout the cell cycle.). Both external and internal signals, trigger increases in the trigger the expression of cyclins that are, specific to each stage of the cell cycle. After the cell moves to the next, stage of the cell cycle, the cyclins that were active in the previous, stage are polyubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome. One such, cyclin, M-cyclin, which is associated with the M-phase of the cell, cycle, is described in Figure 13-8.

Page 15 :

Figure 13-8: M Cyclin. M-cyclin is the cyclin associated with the Mphase of the cell cycle. Cellular levels of M-cyclin steadily grow, throughout the G1, S, and G2 phases. M-cyclin levels are at their, highest during M-phase. After M-phase, there is a sharp decline of Mcyclin levels, as the cyclin is degraded by the proteasome., Cyclins regulate the cell cycle only when they are tightly bound, to Cdks. To be fully active, the Cdk/cyclin complex must also be, phosphorylated in specific locations. Like all kinases, Cdks are kinase, enzymes that phosphorylate other proteins. Phosphorylation activates, the protein by changing its shape. The proteins phosphorylated by, Cdks are involved in advancing the cell to the next phase. The levels, of Cdk proteins are relatively stable throughout the cell cycle;, however, the concentrations of cyclin fluctuate and determine when, active Cdk/cyclin complexes form. The different cyclins and Cdks, bind at specific points in the cell cycle and thus regulate different, checkpoints., In eukaryotes, cyclins and Cdks are designated with letters and, numbers, respectively (examples: Cyclin B and Cdk2). For the

Page 17 :

Figure 13-9: Activation of mitotic cyclin/Cdk complex. The MPhase cyclin/Cdk complex is inactive until inhibitory phosphates have, been removed and activating phosphates have been added to the, protein. This ensures the specific timing of M-Phase cyclin/Cdk, kinase activity in the cell cycle., Another example of cyclin/Cdk activity occurs at the transition, between the G1 and S phases. In G1, proteins needed to initiate DNA, replication and an inhibitory protein called Cdc6 assemble at origins, of replication (Figure 13-10) (refer to Chapter 13 for more on Cdc6, and its role in DNA replication). This is called the pre-replication

Page 18 :

complex and forms to prevent DNA replication until the appropriate, time in the cell cycle. At the beginning of S-phase, the S-cyclin/Cdk, complex phosphorylates proteins in the pre-replication complex to, recruit helicases and DNA polymerases to the origin of replication., The S-cyclin/Cdk complex phosphorylates Cdc6, which inactivates, the inhibitory protein. Collectively, this ensures that DNA replication, occurs, and only once, during the cell cycle., , Figure 13-10: Regulation of the initiation of DNA Replication by, the S-Cdk/cyclin complex. Cdc6 is a protein that binds to the prereplication complex to prevent the start of DNA replication. At the, beginning of S-phase, the S-cyclin/Cdk complex phosphorylates Cdc6, to inactive it. The S-cyclin/Cdk complex also phosphorylates proteins, in the pre-replication complex to recruit enzymes needed for DNA, replication., Negative Regulation of the Cell Cycle, The second group of cell-cycle regulatory molecules is negative, regulators, which stop the cell cycle in comparison to what we just

Page 19 :

discussed where positive regulators cause the cell cycle to progress., The best understood negative regulatory molecules are retinoblastoma, protein and p53., Retinoblastoma (Rb) proteins are a group of tumor-suppressor, proteins, which function to prevent tumor growth by inhibiting cell, division (refer to Chapter 15 for more on tumor suppressors). Much of, what is known about cell-cycle regulation comes from research, conducted with cells that have lost regulatory control. All three of, these regulatory proteins were discovered to be damaged or nonfunctional in cells that had begun to replicate uncontrollably (i.e.,, became cancerous). In each case, the main cause of the unchecked, progress through the cell cycle was a faulty copy of the regulatory, protein., Rb primarily acts primarily the G1-S checkpoint. Rb, which largely, monitors cell size, exerts its regulatory influence on other positive, regulator proteins. In the active, dephosphorylated state, Rb binds to, proteins called transcription factors, most commonly, E2F., Transcription factors “turn on” specific genes, allowing the production, of proteins encoded by that gene. When Rb is bound to E2F, the, production of proteins necessary for the G1/S transition is blocked. In, response to growth factor signaling molecules (refer to Chapter 12 for, more on growth factor signaling) the cell will increase in size. This, triggers the phosphorylation of Rb by the G1-S cyclin/Cdk complex., Phosphorylation of Rb causes its inactivation, resulting in the release, E2F and the expression of proteins needed to progress to S phase, (Figure 13-11).

Page 20 :

Figure 13-11: Retinoblastoma. Retinoblastoma (Rb) binds to and, inhibits the transcription factor E2F. At the G1-S checkpoint, the G1-S, cyclin/Cdk complex phosphorylates Rb in response to growth factor, signaling. When phosphorylated Rb, “releases” E2F. E2F can now, bind to its promoter region to stimulate the expression of genes needed, to advance in the cell cycle, such as cyclin genes., Another important negative regulator of the cell cycle is the tumor, suppressor p53. p53 is a multi-functional protein that has a major, impact on the commitment of a cell to division because it acts when, there is damaged DNA in cells that are undergoing preparatory, processes during G1 (and G2, to a lesser extent). p53 is a transcription, factor that regulates the expression of over 50 genes that control cell, cycle arrest, DNA damage repair, and cell death. Additionally, p53, has transcription factor-independent functions in cells. p53 is often, referred to as the “guardian of the genome” because of the significant, role it plays in regulating the cell cycle.

Page 21 :

One example of the actions of p53 occurs at the G1-S checkpoint, (Figure 13-12). In a resting cell, p53 is produced in the cytoplasm and, rapidly degraded by the cell. If damaged DNA is detected, p53 is, phosphorylated, which stabilizes p53 and prevents its degradation., Phosphorylated p53 translocates to the nucleus where it binds to its, promoter to induce the expression of the gene p21. p21 is a cyclin, inhibitor protein, meaning it can bind to and inhibit the activity of, cyclin/Cdk complexes. Inhibition of cyclin/Cdks by p21 causes the, cell cycle to arrest. This allows time for repair of DNA damage, through the actions of other p53-controlled genes. If the DNA cannot, be repaired, p53 can trigger apoptosis to prevent the duplication of, damaged chromosomes., , Figure 13-12: p53 and p21. The tumor suppressor p53 is produced, and then rapidly degraded by the cell. In response to DNA damage,

Page 22 :

p53 is phosphorylated. This stabilizes p53 and prevents its, degradation. p53 is a transcription factor with over 50 target genes that, collectively control cell cycle arrest, DNA damage repair, and, apoptosis. One of these targets is the p21 which binds to and inhibits, the kinase activity of Cdk/cyclin complexes. When DNA is damaged,, the stabilized p53 increases the expression of p21. p21 then binds to, Cdk/cyclin complexes, causing a “pause” in the cell cycle. This allows, time for DNA damage repair to occur. If the damage cannot be, repaired, apoptosis will be initiated by other p53-target genes., , Cell Death and Cancer, Overview of Cell Death, Cell death can broadly be divided into two categories: unprogrammed, cell death and programmed cell death. Unprogrammed cell death, also, termed necrosis, is a disordered process that results in damage to, surrounding tissue. In response to certain toxins (e.g., brown recluse, spider venom) or injury, cell membranes rupture. Hydrolytic enzymes, and low pH organelles, such as lysosomes and endosomes, are then, released into the extracellular environment. This causes inflammation, and, in extreme cases, the damaged tissue will turn red or black in, color., In contrast to necrosis, programmed cell death (termed apoptosis) is a, highly ordered process. Briefly, apoptosis is initiated by internal or, external signals that indicate the cell should be removed from the, population. This triggers “cell suicide” where the intracellular contents, are degraded. Next, the plasma membrane forms protrusions in a, process called membrane “blebbing.” The blebs eventually break apart, to form apoptotic bodies, which are cleared by phagocytic cells., Because of this, the intracellular contents of the dying cells are not, released, and there is no inflammation or damage to the surrounding, tissue (Figure 15-1). The specific events that trigger and are involved, in apoptosis are outlined in the next section.

Page 23 :

Figure 15-1: Apoptosis versus Necrosis. Panels on the left: Only, green-fluorescing (apoptotic) cells eventually formed apoptotic, bodies. In contrast, necrotic (orange-fluorescing) cells lose their, plasma membranes, do not form such ‘bodies’ and will eventually, disintegrate. Panel on the right: The left hand column shows the steps, in necrosis resulting in inflammation while the right hand column, shows the steps in apoptosis, resulting in clearance of apoptotic, bodies., , Apoptosis, When a cell is damaged, superfluous, or potentially dangerous to an, organism, it can initiate a mechanism to trigger apoptosis. Apoptosis, allows a cell to die in a controlled manner preventing the release of, potentially damaging molecules from inside the cell, thereby avoiding, an inflammatory response. There are many internal checkpoints that, monitor a cell’s health; if abnormalities are observed (i.e., the failure, to pass a cell cycle checkpoint), a cell can spontaneously initiate the, process of apoptosis.

Page 24 :

Apoptosis is essential for normal embryological development. In, vertebrates, for example, early stages of development include the, formation of web-like tissue between individual fingers and toes, (Figure 15-2). During the course of normal development, these, unneeded cells must be eliminated, enabling fully separated fingers, and toes to form. A cell signaling mechanism triggers apoptosis,, which destroys the cells between the developing digits., Initiation of apoptosis, , Internal and external signals can trigger apoptosis. As previously, discussed, checkpoints within the cell cycle serve as “quality control”, mechanisms to ensure that only undamaged cells proliferate., Apoptosis may be initiated by internal signals triggered by various, events, such as checkpoint failure, physical damage to chromosomes, during cell division, or significant debilitating mutations prior to S, phase. If a checkpoint fails, or a cell suffers physical damage to, chromosomes during cell division, or if it suffers a debilitating, somatic mutation in a prior S phase, internal signals will initiate, apoptosis. One example of this is the expression of pro-apoptosis, genes by p53 after the DNA damage is detected., Several external signaling molecules also regulate apoptosis. This, regulation involves the balance between the cell receiving or, withdrawing “survival” signals vs. “pro-death” signals. The continued, survival of most cells requires that they receive continuous stimulation, (or survival signals) from other cells and, for many, continued, adhesion to the surface on which they are growing.

Page 25 :

Figure 15-2: Apoptosis during embryonic development. The, histological section of a foot of a 15-day-old mouse embryo,, visualized using light microscopy, reveals areas of tissue between the, toes, which apoptosis will eliminate before the mouse reaches its full, gestational age at 27 days. (credit: modification of work by Michal, Mañas), Stages of apoptosis

Page 26 :

As previously stated, apoptosis is a highly-ordered process. The major, stages of typical apoptosis are as follows:, 1. Release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria, 2. Formation of the apoptosome, 3. Initiation of the caspase cascade, 4. Breakdown of cellular contents, including chromatin, 5. Membrane “blebbing”, 6. Phagocytosis of apoptotic bodies, Apoptosis begins with the release of a mitochondrial protein,, called cytochrome c, into the cytoplasm in response to internal or, external signals. The release of cytochrome c is regulated by a group, of proteins with competing functions. The anti-apoptosis protein Bcl2 inhibits cell death by sequestering cytochrome c in the mitochondria., In contrast, the pro-apoptosis proteins Bak and Bax promote the, release of the cytochrome c into the cytoplasm, initiating apoptosis., This specific mechanism of action is still not fully understood., However, it is believed that Bak and Bax form a pore in the, mitochondria, allowing cytochrome c to be released. Conversely, Bcl2 is thought to either prevent Bax/Bak pore formation and/or serve as, a “plug” to prevent cytochrome c diffusion through the pore., After exiting the mitochondria, cytochrome c binds to adaptor proteins, and pro-caspase 9 to form a structure called the apoptosome. Procaspase 9 is a member of a class of enzymes called caspases, which, are proteolytic enzymes (enzymes that break down proteins; also, called proteases). The “pro” in pro-caspase 9 indicates that the enzyme, is in its inactive proenzyme (procaspase) form, meaning it cannot, break down proteins. Shortly after the formation of the apoptosome,, pro-caspase 9 is converted to the active protease caspase-9. This

Page 27 :

occurs when the pro-domain, a part of the protein that inhibits enzyme, activity, is removed from the caspase (Figure 15-3, A)., , Figure 15-3. Caspases. (A) Pro-caspases are inactive proteases, (proteases are enzymes that break down proteins). Pro-caspases, become caspases (active proteases) after removal of the pro-domain, on the pro-caspase. (B) During the early stages of apoptosis, procaspase 9 (green) in the apoptosome is converted into caspase 9., Active caspase 9 can then cleave the pro-domains off of other, caspases, such as caspases 3, 6, 7 (blue). (C) A few caspases can, activate a small population of caspases, which can then go on to, activate a larger caspase population. This cascade effect leads to a lead, large number of active caspases in the cell, which then breakdown, cellular proteins and chromatin.

Page 28 :

In addition to caspase 9, there are many other caspases in the cell,, which exist in their inactive, procaspase form. After the conversion of, pro-caspase 9 to caspase within the apoptosome, caspase 9 cleaves the, pro-domains from a small population of pro-caspases 3, 6, and 7, proteins to form active caspases 3, 6, and 7 (Figure 15-3, B). These, active caspases then cleave pro-domains from other pro-caspases,, increasing the number of active caspases within the cell (Figure 15-3,, C). Thus a cascade effect occurs, called a caspase cascade (also called, a proteolytic cascade), after the initial activation of one set of, caspases. Ultimately, the active caspases breakdown chromatin and, proteins within the cell (Figure 15-4).

Page 29 :

Figure 15-4: The role of caspases in apoptosis. In a cell that is not, undergoing apoptosis, caspases exist in their proenzyme form,, meaning they are inactive. When released from the mitochondria,, cytochrome c binds to adaptor proteins and the proenzyme caspase 9, to form a structure called the apoptosome. The formation of the, apoptosome triggers caspase 9 to become an active protease. The, apoptosome (with active caspase 9) converts several caspases, (examples: caspases 3, 6, and 7) from their proenzyme forms into their, active forms. Active caspases break down cellular proteins, and, convert other caspases from their proenzyme to their active form., Collectively, this forms a cascade of amplifying caspase activity,, resulting in apoptotic cell death, Once active, caspases degrade chromatin and proteins within the cell., As a result, the cell begins to shrink and lose shape as the cytoskeleton, is degraded. Then the organelles appear to pack together, except for, the nucleus. Inside the nucleus, the chromatin condenses and attaches, to the nuclear envelope, which then loses its integrity and starts to, break apart. The cell membrane begins to show irregularities,, descriptively known as blebs, and eventually, the cell breaks apart, into vesicles called apoptotic bodies that are neatly cleaned up by, phagocytes drawn to the site by apoptotic signals emitted by the dying, cell (Figure 15-5), One important note is another form of apoptosis, sometimes called, extrinsic apoptosis, which does not utilize cytochrome c. Instead, in, these forms of apoptosis, the caspase cascade is directly activated by, pro-cell death receptors. After initiation of the caspase cascade,, membrane blebbing and formation and clearance of apoptotic bodies, occur as previously described.

Page 30 :

Figure 15-5: Membrane blebbing and apoptotic bodies. Active, caspases breakdown proteins in the cell. This results in cell shrinking, and fragmentation of the nucleus. The cell membrane protrudes in a, process called membrane blebbing. Blebs will eventually break off, and form vesicles called apoptotic bodies. Apoptotic bodies are then, engulfed by phagocytic cells.