Page 1 :

aan Principles : Self-Pollinated, II Crops, , , , , , Selection in Self-Pollinated Crops, , 9.1. INTRODUCTION, , In self-pollinated crops, selection permits reproduction only of those plants that have the desirable, _characteristics., ie, the | plants that have been selected. This is achieved by raising the next, “generation from seeds of the selected plants only. Selection, as a rule, is based on the phenotype, of plants. Consequently, the effectiveness of selection primarily depends upon the degree to, which. phenotypes of plants reflect.their genotypes. Selection has the following two. basic, features: (YF it is effective for heritable differences only and its effectiveness is greatly affected, by-heritability of the character under selection, and (2) it does not create new variation; it only, utilizes the variation already present in-a population. Thus the two requirements for selection to, be. effective are, (1) variation must be present in the population, and (2) this-variation must be, heritable. The purpose of selection is to isolate desirable plant types from a genetically variable, population., , 9.2. HISTORY OF SELECTION, , After domestication, crop species were exposed to both, natural and artificial selections. For a, long period under domestication, natural selection was perhaps more important than selection by, humans. But in modern plant breeding methods, natural selection is of little value, and they are, based entirely on artificial selection. There is evidence that selection was practised by farmer$, in ancient times. During late eighteenth century, selection by agriculturists, such as Van Mons, in Belgium, Andrew Knight in England and Cooper in U.S.A., resulted in several important crop, varieties. Le Couteur, a farmer of the Isle of Jersey, published his results on selection in wheat., in the year 1843. He-concluded that progenies from single plants were more uniform than.the, , temaining population, and that different progenies were of different agricultural value. About the, same time, a Scotsman named Patrick Shireff practised individual plant selection in wheat and, oats, and developed gome valuable varieties., , Scanned with CamsScanner

Page 2 :

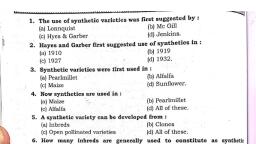

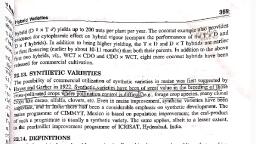

162 Plant Breeding : Principles and Methods, , Some years later, beginning in 1857, Hallet in England practised single plant selection in, wheat, oats and barley. He believed that acquired characters were inherited. Therefore, from the, best plants, he selected the best spike from which he selected the best grain. Hallet developed, several commercial varieties, ¢.g., Chevalier barley. About this time, MR propoeet individual, , i This method successfully improved the sugar content, in sugarbeets (Beta vulgaris) in 12 years, but 50 years of selection was ineffective in improving, four wheat varieties. This clearly demonstrated the difference between effectiveness of selection, in self- and cross-pollinated species. But the genetic basis for this difference was understood only, later when the i i sen in 1903. The Svalof, experiment station of Swedish Seed Association, estabilished in 1866, refined the single plant, selection or pureline selection to its present form., , 9.8. PROGENY TEST, imati i eniesis known as, , t. Progeny test was developed by Louis de Vilmorin; therefore, it-is'also known as, or, in short, Vilmorin principle. Vilmorin observed that sugarbeet, , plants with high sugar content could be grouped into three classes based on the sugar contents, of their progenies. The first group of plants produced progenies high in sugar content, the, progenies from the second group had some plants with high and some with low sugar content,, while the third group produced progenies low in sugar content. Thus plants similar in phenotype, (high sugar content) produced considerably different progenies. From these observations, Vilmorin, concluded that the.real-value-of a’plant canbe known only:by studying its progeny., , Today, progeny test is the basic step in every breeding method. ion, , ts : (1) thesbreeding» behaviour of a. plant, i.e.,”, , on.the. following two valuable*and useful aspec, , whether it is homozygous*or heterozygousand (2) whether the. feature for. which.a plant was, selected-is heritable. If the phenotypic superiority of selected plants were due mainly to their, genotype, their progeny will also exhibit that superiority. But if the superiority were due to, environmental factors, progeny will not exhibit the superiority (Section 9.4)., , 9.4. THE PURELINE THEORY, ies. Therefore,, , all the plants in a pureline have the same genotype, and the phenotypic variation within»a, eline 1 ronment alon and Oe ee ie SUITES of purelines was, proposed by 3Jon the basis of his studies with (Phaseolus vulgaris),, i h, , a strictly self-pollinated species. He obtained commercial seeds of the Pri, , bean, which showed variation for seed size. He selected seeds of different sizes and grew them, and harvested their seeds separately. Seeds from each selected plant were grown separately as, , individual plant progenies, which differed in seed size: progenies from larger seeds generally, produced larger seeds than those obtained from amelie? mec TE clearly, lace ae Be, variation in seed size in the commercial seed lot of Princess had a genetic basis, as a result of, which, selection for seed size was effective. Johannsen further studied 19 lines, each of which, , “was progeny of a single seed from the original ‘Seed Tot. He discovered that each line showed 4, — i ight, > i slainaahl RGdemnsinalainaell 19, , ig. 9. 1). The seed size within'‘a line showed some variation, which was much smaller than that., present in the original commerctat seed Tot: Johannsen postulated that the original seed lot_was, , , , , , , , Scanned with CamScannér

Page 3 :

Selection in Self-Pollinated Crops 163, , . PRINCESS BEAN, (Commerciat seed lot), , TTL AN\\\ tn et., , Progeny from individual seeds) different sizes selected, to ralse individual seed, | | \ \\ progenies, Line No. 1 13 19, Mean seed ¥ : | = ., weight (mg) 640 450 350, Selection Ps. WS., fe tae porcenon Seed weight classes Seeds classified into, and smallest, seeds \ aa 100 mg classes, Largest Smallest 200 300 400 500 E, seed seed | |, Selection Progenies, Selection for } ), seed size Mean seed weight of the, = Largest Smallest, continued a eeed 475 450 451 458 progenies (mg), , generations, , Selection +, continued, Mean seed | |, weight(mg) 680 690, , Fig. 9.1. Selection for seed weight in a commercial seed lot of the Princess variety of Frerich bean by, Johannsen (1903)., , a mixture of purelines. Thus each of the 19 lines represented a pureline, and the variation in seed, size within each of the purelines had no genetic basis and was entirely due to environment., , _Confirmatory evidence was obtained in the following three ways: (1) Johannsen classified, seeds from each pureline into 100 mg classes, and grew them separately. The mean seed weights, of progenies from the different seed weight classes of a single pureline were comparable with, each other, and with that of the parent pureline. For example, Line No. 13 had seed size classes, of 200, 300, 400 and 500 mg. The mean seed weights of the progenies derived from these seed, weight classes were 475, 450, 451, and 458 mg, respectively (Fig. 9.1). (2) From each pureline, Johannsen selected the largest and the smallest seeds to raise the next eneration. In the subsequent, generations, largest seeds were seca ih He wosenies Oieed Come largest seeds, while, , Largs, , in those derived from the smmatiest seeds selection was done fo allest seeds. Six generations, of selection was ine, , increasing or decreasing the seed size. For example, alter six, generations of selection, the mean seed weight in Line No. 1 was 690 and 680 mg in the, progenies selected for small and large seeds, respectively (Fig. 9.1). Thus selection within a, pureline was ineffective. = =, poe Ee, , , , + Finally, Johannsen estimated parent-offspring correlation. The value of parent-offspring, correlation within Line No. 13 was -0.018 + 0.038, that is, zero, while it was 0.336 + 0.008 in, , Scanned with CamsScanner

Page 4 :

164 Plant Breeding : Principles and Methods, , the original seed lot of Princess, which is highly significant. The-parent-offspring correlation wi, be.zero when. the variation is nonheritable, while it will /be significantly greater than zero when, it has a genetic basis, i.e., is heritable. These observations reveal that the variation for seed size, in the original seed lot of Princess had a genetic basis and was herritable. But the variation within, the purelines obtained from the single seeds selected from this seed lot -was purely due to the, environment and, therefore, nonheritable. The-two-main-conclusions from the Johannsens’, experiment are as follows., , 1. A. self-fertilized-population. consists-of a mixture of several homozygous genotypes., Vartation-in-such-a population -has-a»genetic. component, and, therefore, selection is, effective., , 2. An. individual-plant~progeny~selected from-a-self-fertilized population consists of, homozygous. plants. of identical.genotype. Such-a progeny is known as pureline. The, variation present within.a-pureline is purely environmental and, as a result, selection, , within-a_pureline is ineffective., , 9.5. EFFECTS OF SELF-POLLINATION ON GENOTYPE, , Self-pollination increases homozygosity with a corresponding decrease in heterozygosity. Inbreeding, also increases homozygosity and reduces heterozygosity. Inbreeding is mating between individuals, related by descent, that is, having’a common parent or parents in their ancestry. Some examples, of inbreeding are, sib mating (brother-sister mating), half-sib mating (brother-stepsister mating),, etc. Self pollination is the most intense form of inbreeding, since in this case the same individual, functions as the male as well as the female parent., , The effect of self-fertilization on homozygosity and heterozygosity may be illustrated by an, example. Suppose an individual is heterozygous for a single gene (A/a) and the successive, generations derived from it are subjected to self-pollination. Every generation of self-pollination, will reduce the frequency of heterozygote Aa to 50 per cent of that in the previous generation., There is a corresponding increase in the frequency of the two homozygotes AA and aa. As a, result, after 10 generations of selfing, virtually ail the plants in the population would be, homozygous, ie., AA and aa, and the frequency of heterozygote Aa would be only 0.097 per, cent, i.e., negligible (Table 9.1). It is assumed here that the three genotypes AA, Aa and aa have, equal survival. If there is unequal survival, it may increase or decrease the rate at which, homozygosity is achieved. If Aa is favoured, the rate of increase in homozygosity would be lower, than expected. But if Aa is selected against, homozygosity would increase at a faster rate than, expected. When a number of genes are segregating together, each gene would become homozygous, at the same rate as Aa. Thus the number of genes segregating does not affect the percentage of, homozygosity. The term homozygosity denotes the frequency of genes in homozygous condition, in the population. Similarly, linkage between genes does not affect the percentage of homozygosity., , Another, way of visualising the effect of self-pollination is to consider the frequency of, plants, which are homozygous for all the genes. In-case.of.a-single-gene; the frequency of, completely-homozygous plants in a generation is.the-same.as the proportion of homozygosity:, But when two or more genes are segregating, the proportion of homozygosity increases ata much, , faster rate than that of completely homiozygous plants. The proportion of completel homozygous, plants is given by the following formula. | pe i, , Proportion of completely homozygous. plants.=.{(2"~1)/2"]", , Scanned with CamsScanner

Page 5 :

Selection in Self-Pollinated Crops 165, , where, m_is the number of generations of self-pollination and n is the number of segregating, genes. The proportion of completely homozygous plants under self-pollination is depicted in Fig., 9.2. It is clear that as the number of gehes increases, the proportion of completely homozygous, plants after a given number of generations of selfing decreases. But the effect of selfing is so, strong that even if 100 genes were segregating, more than 95 per cent of the population would, , TABLE 9.1. Effect of self-fertilization’ on the frequency of homozygotes with respect to a, , single locus A/a. This also gives the degree of homozygosity with respect to any, _ number of genes ., , , , , , , , Number of Frequency (%) Frequency (%), generations of AA Aa aa Homozygotes Heterozygotes, self-fertilization (or homozygosity) (or heterozygosity), , 0 0 100 0 0 100, , 1 25 50 25 50 50, , 2 (25 + 12.5) 25 (25 + 12.5) ‘6 25, , 3 (37.5 +625) 12.5 (37.5 + 6.25) > 87.5 12.50, 4 (43.75 + 3.125) © 6.25 (43.75 + 3.125) 93.73 6.25, , 5 (46.875 + 1.562) 3.125 (46.875 + 1.562) 96.874 3.125, 6 (48.437 + 0.781) 1.562 (48.437 + 0.781) 98.436 1.562, 1 (49.218 + 0.390) 0.78) (49.218 + 0.390) 99.216 0.781, 8 (49.608 + 0.195) 0.390 (49.608 + 0.195) 99.606 0.390, 9 (49.803 + 0.097) 0.195 (49.803 + 0.097) 99.800 0.195, 10 (49.900 + 0.048) 0.097 (49.900 + 0.048) 99.896 0.097, , = 49.948 = 49.948, 4" [@"-1y/2"*"] (1/2") (@"-1/2"*7] epay —Rye, , , , *The formulae give proportions rather than per cent values., , , , 100:, , 755, , 50-5, , 25-4, , COMPLETELY HOMOZYGOUS, INDIVIDUALS (%), , , , , , , , ‘ mT 1, 0 2 4 6 8 10. +12, GENERATIONS OF SELF-POLLINATION, , Fig. 9.2. Per cent of completely homozygous individuals after different generations of self-pollination;, the curves represent values when 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 and 100 genes are segregating., , , , Scanned with CamsScanner