Page 1 :

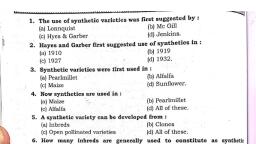

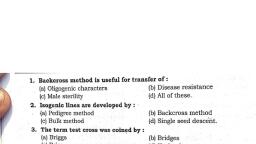

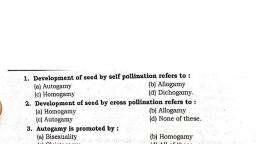

Domestication and, Germplasm Conservation, , 2.1. DOMESTICATION, , The present-day cultivated plants have been derived from wild weedy species. The first step in, the development of cultivated plants was domestication, i.e., bringing wild species under human, management, which began over 11,000 years ago when humans bagan agriculture. The first, domesticated plants were cereals, legumes and other species used for their fruits or roots. Most, of the crops were domesticated by the prehistoric humans, who either knowingly or unknowingly, must have selected for those characteristics that made the plants more suited to their needs, which, ‘are likely to differ from those for which the wild species would have been selected for in nature., As a result, the two groups of plants would have developed in two different, often Opposite,, directions. Presumably, characters like shattering and dormancy would have been rapidly eliminated, , i d species. Eventually, crop plants have diverged from their wild ancestral Species, pa ee ey are classified as distinct species, and in some cases their wild ancestors, , ‘O remarkably, , are not easy identi ae species is likely to continue for a long time in the future since human, Doineieenion © ith time, and the wild species of little importance today may assume, needs are likely to See THE is particularly true for forest trees producing timber and other, ne dicinal plants, and plants fulfilling specific needs. A notable case of, commercial products, me ication relates to several plant species for production of biofuels., recent and continuing ee curcas), a member of Euphorbiaceae family, cultivation is being, For example, jatropha (Jatrop - om its seeds is used to produce biodiesel, which is supplemented, popularised since oil oneae + ati has medicinal value, is used as spice, and its leaves enrich, (up to 5%) in diesel. This Oe persicum), a perennial spice, was domesticated during 1990s in, i carbon. Rel hae cultivated as an orchard crop., imachal Pradesh,, , , , great significance tomo, , til, = Scanned Witt Camocanne, , T

Page 2 :

a6 Plant Breeding = Principles and Methods, , 2.1.1. Selection under Domestication, different rates, it is called selection., , When different genotypes present in a population re) roduce at freely Wi, population may be defined as the group of individuals, which mate Of can_mate freely with, , cach other. Ths 4 population consists of individuals of a single species growing.in Hie same, ficial, depending on the agency responsible, , locality. Selection is known as (J) natural or (2) arti, — a“, , for it., 2.1.1.1. Natural Selection. Selection due to natural forces like climate, ss ao, factors, e.g., diseases, insect pests, etc.. and other factors of the environment - : led natural, selection. It Occurs in natural populations, é.e., wild forms and wild species, an etérmines Tie, ion reproduce, the population, , course of their evolution. Generally, all the genotypes of the populati ; bility §, becomes more adapted to the prevailing environment, and considerable genetic variability ts, , retained. In 1962, Nicholson proposed that natural selection may be seen to operate through two, mechanisms, viz, (1) environmental selection and (2) competition. Environmental selection acts, against all such genopypes that are unable to cope with the environmental stresses. AS a result,, the population consists, ultimately, of only those genotypes that are capable of surviving the, prevalent environmental stresses and are also able to reproduce. Natural selection through, competition occurs in crop populations where a plant takes up more water, nutrients or light than _, another, and at the expense of the other. Therefore, the more successful is a plant in exploiting, resources, the greater will be its potential to be represented in the succeeding generations and it, , will be selected through competition., 2.1.1.2. Artificial Selection. In contrast, artificial selection is carried out by humans, and, , is confined to domesticated species. It allows only the selected plants to reproduce, ordinarily, , makes plants more useful to humans, and generally leads to a marked decline in genetic variability, , in the selected progenies/populations. sually, plants become less adapte natural, , énvironment, and they have to be grown under carefully managed conditions. Our present-day, crops are the products of continued artificial selection., , 2.1.2. Types of Selection, , Selection is grouped into the following three types depending mainly on the type of phenotypic, class favoured by it: (1) directional selection, (2) stabilizing selection, and (3) disruptive selection., In plant breeding situations, selection is almost always directional aiming to achieve the maximal, expression of targeted characters. In nature, however, selection would be either directional,, stabilizing or disruptive depending on the state of evolution of the population. While a population, is adapting to new environmental conditions (either in a new area where it has been introduced,, or in the same region after a change in the environment) there will be directional selection to, increase its fitness. But once the population has become adapted, directional selection will be, succeeded by stabilizing and disruptive selections., , 21.2.1. Directional Selection. When individuals having the extreme phenotype for a trait, or a group of traits are selected for, it is called directional selection. Directional selection usually, selects for such gene combinations that produce a fully balanced phenotype; such a phenotype, results in the maximum yield under artificial selection, and in the maximum fitness under natural, ae an such . combinations are established, they are protected from further changes, polliatic = self pollin ee by a change in the mode of reproduction, e.g., from cross", , Scanned with CamScannef

Page 3 :

Domestication and, Germplasm Conservation 17, , In cross-pollinated Populations, directional sel, , . . a octit il fy - a . iy oni ce, in the appropriate direction, ection will favour alleles showing dominance, , and genes showing ‘desirable’ epistatic interactions will also be, , selected for. As a result, character: ', irecti i ; tcters subjected to prolonged directi selection will show high, directional dominance and/or epistais E nged directional selecti ig, , 2.1.2.2. Stabilizi . ,, . ilizing Selection, When selection favours the intermediate phenotype and acts, against the extreme phenot i i pe and, “Sicction, ant and qive oe itis termed as stabilizing selection. In nature, it follows directional, S U ainbas,, a . a . thn es to maintain the co-adapted gene complexes generated by the latter. It may, pointed out that for such characters that directly affect fitness, e.g., viability and fertility., , selection will always be directional. Therefore, stabilizing selectioh occurs only for those traits, that do not affect fitne: typic expression, , directly, and it favours those genotypes whose phenotypic, , , , , , , , , St ng selection disfavours dominance; if dominance is present,, it is bidirectional, i.e., some alleles show dominance in one direction, while some others show] tgdominance in the opposite direction. Similarly, epistasis is also selected against. Thus stabilizing,, selection accumulates alleles showing additive gene action. >, , 2.1.2.3. Disruptive Selection. This type of selection succeeds directional selection in such, natural populations that are subjected to distinct ecological niches that may be spatial, temporal, (seasonal or long-term cycles) or functional (e.g., males and femals of species) in nature. In each w, ‘ecological niche’ a different ‘phenotypic optima’ is selected for so that the population ultimately, consists of two or more recognizable forms; such a selection is catled disruptive selection. The, consequences of such a selection depend mainly on the following two factorsi47 whether the, different optimal phenotypes are independent of or dependent on each other for their maintenance, or function, and (7 the rate of gene flow between them. For example, the male and female forms, of a single species are completely interdependent in function, ie., reproduction, and show 100%, gene exchange. At the other extreme, a species may occupy a habitat that is fragmented into two, or more independent niches, and in each niche a different phenotypic optima is selected for, In, such a case, if the selection pressure is high enough and continued long enough, genetic barriers, to crossing may arise leading to genetic separation of these forms, and eventually to their, , evolution as distinct species., , Disruptive selection maintains polymorphism in a population. Further, it shows such features, as frequency-dependence (e.g., less frequent alleles eing more favoured), density-dependence,, cyclical nature, etc.: a discussion of these aspects is beyond the scope of this book. Since, , ‘directional’ in nature within each ‘ecological niche’ of the habitat, it, , disruptive selection is : :, oe i epistasis. In addition, it often leads to the establishment of integrated, favours dominance and €P! J vnecies: A ' resent QF tnt “we, ‘supergenes’, €.g., in case O) male and female forms of a species. A ‘supergene’ is a set of closely, linked genes that together lead to the development of a specific optimal phenotype, e.g., male or, , a, , female form., , 2.1.8. Changes i, , , , n Plant Species under Domestication, , The precise sequence of events during the evolution of crop plants under domestication is not, known. Presumably, in the initial stages, considerable genetic variability existed in each, domesticated species. This variability was acted upon by both natural and artificial selections, it, may be expected that humans always tried to pick out the plant types, which better suited their, needs, For example, they would obviously have selected for larger fruits and seeds. Our record, of planned and systematic selection goes only as far back as middle of the nineteenth century., , Scanned with CamsScanner

Page 4 :

Plant Breeding :, , 18, , Before this period, selection efforts wou, focus. But judging from the results, i-e.,, the then completely unscientific humans were, , Domestication of crops is believ:, six regions: (i) Mesoamerica, (if) the Sou, the Sahel and the Ethiopian highlands), (v) South East-Asia,, geographical diversity of these centres, a remarkably similar se, selected in widely different crops; these traits are called domestic, 2.1). Almost all the characteristics of plant species have chang!, accumulation of spontaneous mutations. The characters that shi, that have been objects of selection and are still plant breedin, species. Some of the important changes that have occurred und, , 1. Elimination of or reduction in, of the cultivated species., XX. Elimination of dormancy has taken place in s', , has become a problem i, , Decrease in toxins ot other undesirable substances, , bitter principle of cucurbitaceous plants provi, 4. Plant type has been extensively modifi, , branching, Teaf characters, etc., Jranching, <a, , 5. In several crop species,, etc. This is often associated w, , the differentiation of crops, , 6. In some species,, domestication, e.g. jute (Corchorus sp., , Id obviously have been primitive, anise, from their wild prototypes,, , not bad plant breeders at all., , ed to have occurred independently i, , them Andes, (iii) the Near East, (, and (vi) China. In spite of the, , t of traits seems to have been., ation syndrome traits (Table, , shattering of pods, spikes, etc. has taken p!, , there has been a decrease in plant height,, ith a change from indeterminate to determinate habit., , on the other hand, there has been an increase in plant height under, , ) sugarcane (S. officinarum), forage grasses. € ic., ge g, , Principles and Methods, , unorganised and lacking, , in the following at least, (iv) Africa (probably, , ed under domestication due to, ow more distinct changes are those, g objectives in many cultivated, er domestication are listed below., , lace in most, , everal crop species. Lack of dormancy, n crops like barley, wheat, mungbean, etc., , has occurred in many crops. The, des an example of this type. ~~, ed. The cultivated plants show altered tillering, , e.g., cereals, millets,, , TABLE 2.1. The different traits comprising domestication syndrome, , Selected trait, , Selection at growth, Specific trait, , stage General feature, , Loss of seed dormancy, , Increased seedling vigour, , Seedling, Increased rate of selfing, , Reproductive, , Adoption of vegetative, reproduction, , Loss of seed dispersal, , More compact growth habit, Increased number or size of, inflorescence, , Increased number of grains/, inflorescence, , Changed photoperiod, sensitivity, , Colour, size, taste, texture, , Reduction in toxic, substances, , larvest or after Increase in seed yield, , harvest, , , , Example crop(s), , Many crops, e.g., mungbean, Tomato, Sunflower, B., juncea etc., , Sugarcane, cassava, etc., Legumes, , Legumes, , Maize. wheat, , Maize, , Legumes, rice, , Many crops, , Cassava. lima bean,, cucurbits, , Scanned with Gamiseannet

Page 5 :

omestication and G, D iermplasm Conservation 19, , 7. Life cycle has become Shorter in case of, , = s _ i icularly inc lik, cotton (Gossypium SP.), Pigednpea (Cebus crop species, particularly in crops like, , 8. Most of the cro nus cajan), etc., P Plants show an increase in size of their grains or fruits., , . Increase in e ic yield j, do} in economic yield is the most noticeable as well as desirable change under, mestication in every crop species, , , , 10. In man: ‘i eae, 'Y CTOp species, asexual reproduction has been promoted under domestication,, , e.g., Sugi, 8 garcane, potato (Solanum tuberosum), sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas), etc., , There . j, , doce ween a preference for polyploidy under domestication. Many of the, , a ticate plant species are polyploids, e.g., potato, wheat, sweet potato, tobacco, , icotiana sp.) etc., while diploid counterparts are present in nature., , 12. In many species, there has been a shift in the sex form of the species. In many, dioecious fruit trees, bisexual forms have developed under domestication. Selfincompatibility has also been eliminated in several crop species., , 13. Variability within a variety has drastically decreased under domestication. The extreme, , case is represented by pureline varieties, which are completely homozygous and consist, , of a single genotype., , 11., , , , 2.2. PATTERNS OF EVOLUTION IN CROP PLANTS, , It is apparent that selection by nature and humans has been responsible for the evolution of crop, plants. However, selection is effective in altering a species only when genetic variability exists, in the populations of that species. There are three major ways in which genetic variability has, arisen in various crop species, viz., (1) Mendelian variation (generated mainly by gene mutation),, (2) interspecific hybridization, and (3) polyploidy. The patterns of evolution of various crops are, therefore, considered here according to the mode of origin of genetic variation crucial for evolution, , of that species. g, , 2.2.1. Mendelian Variation, , Many crops have evolved through variation generated by gene mutation, and by hybridization, between different genotypes within the same species, followed by segregation and recombination., Ultimately, all the variability present in any species has. originated from gene mutations. Most of, the gene mutations are harmful and are eventually eliminated. But some mutations are beneficial, and are retained in the population. Mutations may be grouped into two broad categories: (1), , macromutation and (2) micromutation. A macromutation produces a large and distinct, , morphological effect, and often affects several characters of the plant. A single macromutation, is believed to have led to the differentiation of modern maize (Zea mays) from the grassy pod, d the positions of male and female inflorescences, habit of the, , com. This mutation has affected the, plant and several other characters. Similarly, cabbage (Brassica oleracea vat. capitata), cauliflower, , (B. oleracea vat. botrytis), broccoli (B. oleracea var. italica), and Brussel’s sprouts (B. oleracéa, var. gemmifera) have all originated from a common wild species and they differ from each other, with respect to a few major genes., , The greater part of genetic variation, however, has resulted from mutations with small and, less drastic effects, i-€., micromutations. Since micromutations have only small effects, they tend, to be accumulated in a population as a consequence of natural selection. Humans would have, selected for desirable plant types leading to the differentiation of domesticated species from the, , Scanned with CamsScanner