Page 2 :

Physical Optics, , a, , on of light through a certain angle. This phenomenon, ‘opti rotation’ or ‘rotatory polarisation’. The, substances which rotate the plane of pol, “optically-active”, and the property is called ‘optical activity”., If plane-polarised light emerging from a Nice! «9, is, examined through another Nicol N, , it is completely cut off when, , , , , , , , , , , , , , Sr, , , , ANALYSER, , , , , , , , (Fig. 1), , the principal section of NV, is perpendicular to that of NV, But if, a quartz plate C (Fig. 1) cut with optic axis perpendicular to its, face* be placed between N, and N,, some light begins to pass, through N,. The light is, however, again completely cut off if NV,, is rotated through a certain angle. This shows that the light emerging from the quartz plate is still plane-polarised, but its plane of, polarisation has been rotated by the plate through a certain angle., Thus quartz is optically-active. Many liquids and organic substances in solution (as cane-sugar) are found to be optically-active., , There are two types of optically-active substances. Those, which rotate the plane of polarisation clockwise (looking against, the direction of light) are called ‘dextro-rotatory’ or ‘right-handed’,, while those which rotate anti-clockwise are called ‘leavo-rotatory’, or ‘left-handed’. Quartz occurs in both forms, The rotation produced by a plate 1 mm thick is called the ‘specific rotation’, For, sodium light, the specific rotation of quartz is 21°7°., , Biot, in 1815, studied the phenomenon in detail and gays, the following laws :, , (The angle of rotation of the plane of polarisation, for a, given wavelength, is directly proportional to the length of the opti, cally-active substance traversed., , (ii). For solutions and vapour, the, angle of rotation for a given pathlength is proportional to the concentration of the solution or vapour,, , Gii) The rotation produced by a, number of optically-active substances is, equal to the algebraic sum of individual, Totations. The anti-clockwise and clockwise rotations are taken with opposite =, signs, Fig. 2), , ‘in this case there is no double refraction in the plate., , , , , , , , , , , , , , +, , , , Optical Rotation 285, , (iv) The angle of rotation is approximately inversely proportional to the square of waveleagth. More accurately for quartz., we have, , angle of rotation=A +2 ., , Thus, if white plane-polarised light having vibration in the direetion AA (Fig. 2) be incident normally on a quartz plate, the, different colours are rotated through different angles, as shown., The field of view, therefore, appears coloured. This phenomenon, , is called ‘rotatory dispersion’., , Fresnel’s Theory of Optical Rotation—It is based on the, principle of dynamics that a linear vibration may be described as, the resultant of two opposite circular motions of the same frequency.t He made the following assumptions :—, , (i) The incident polarised light on entering a substance is, broken up into two circularly-polarised waves, one clockwise and, , the other anti-clockwise., , (ii) In an optically-inactive substance the two waves travel, with the same velocity, but in an optically-active substance they, travel with diferent velocities. (In a dextro-rotatory substance, the clockwise wave travels faster, while in the leavo-rotatory, substance the anti-clockwise wave travels faster). Hence a phase, difference is developed between them as they traverse the substance., , (iii) On emergence, the two circular components recombine, to form plane-polarised light whose plane of polarisation is rotated, with respect to that of the incident light by an angle depending, on the phase difference between them., , Suppose that plane-polarised light is incident normally on a, quartz plate cut perpendicular to the optic axis. Let the first face, of the plate be in the x, y plane. Let the vibrations in the incident, light be represented by, , V=a COS wt, -), , These vibrations, just on entering the crystal, are broken up into, two equal and opposite circular motions (Fig. 3 a) hick are, represented by :, , m= 4S sin ot clockwise, , a 5 : r, Y= = COS wf circular-motion GDF, , This has been proved in the beginning of the chapter.

Page 3 :

Physical Optics, , 286, y= = sin wi anti-clockwise, and y= = cos wt circular-motion ...(iii)*, These circular components are propagated through the plate, hen they emerge from the, , with different velocities. Therefore, W, fference 3 (say) between them. Suppose, , plate, there is a phase di, y, |, , aba, , te), , , , , , , , (Fig. 3), that the clockwise component advances infront of t, (Fig. 3b). The emergent circular component can, , represented by, , he other, then be, , n= sin (wt +8) y= = sin ot, ie and, a : a, Pray 8 (wt +3) n= 7 8 wt., The resultant displacements along the two axes are, x= ty = + {sin (wt+8)—sin ot], , = a cos (a + 5) ame . .-fiv), , , , ly represent circular motion because, and x2+y2= = . On superposition they give rise, (i). This is so because the resultant displace, "The pairs (ii) and (iii) individual, a, they give xfe= =, to the linear motion given by eq., ment along the x-axis is, x=xy+x_=0,, and that along the y-axis is, ymeyrt yr: a COS wf., These two when compounded give a resultant, yma COS wl,, , shich is ea. (), at, , Optical Rotation, , and yanthe = S feos (wt-+8)-+008 a], , =acos (»« + 4) cos 5. o(v), , Dividing eq, (iv) by eq. (v), we have, x 5, —=tanzy, This represents a_ straight line inclined at an angle 8/2 to the, y-axis (Fig. 3 6). Hence the light emerging from the plate is, plane-polarised, with vibrations inclined at angle $/2 to the »-axis,, that is to the vibrations in the jncident light. Thus the quartz, plate has rotated the plane of vibration by 3/2., If wz and yc are the refractive indices of quartz in the direction of the optic axis for anti-clockwise and clockwise circularlypolarised light respectively and d is the thickness of the crystal, plate, then the phase difference 8 is given by, , 2:, B= F (Hanne) 4., , Hence the rotation of the plane of vibration (or, of the plane of, , polarisation) is, 3b _ xd, t= (#4—He), Experimental Verification of Fresnel’s Theory—To verify, Fresnel’s theory, a beam of pee enee light is made to fall, normally on a rectangular block ABFG (Fig. 4). The block is, made of alternate prisms of right-handed and left-handed quartz,, all having their optic axes perpendicular to the end faces 4B and, FG. If the Fresnel’s hypothesis is correct, this plane-polarised, light will break up into two opposite circularly-polarised waves, (Left-handed and ight-handed) which travel the first prism with, different velocities but in the same direction. Upon passing ., through the first oblique boundary BC, the R-wave which was, faster in the first prism (R-prism) becomes the slower in the, second. The opposite is§truejfor the L-wave. Hence the second, , , , == ——, , , , (Fig. 4), prism (L-prism) is a denser medium for the R- and rare!, the Z-wave. Hence in the second caer 1 late bead jose, , the base (downward), and the L-wave awa’, At the second boundary CD, the Aeloonineace Skeet

Page 4 :

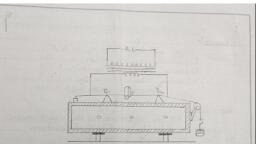

Physical Optics, , a detectable separscs., , , , working of a Laurent’s balf-shade polarimeter, explaining fully the, action of the balf-shade device. How you would use it to determine, , trument used, es. Its optical, , , , for measuring the optical rota, parts are shown in Fis. 5., Moaochrematic &, aher passing throug?, aad falls on & 50 F, light becomes pis: passes through 2 half, 2 S, usually a sodium lamp,, 1 by a convex lens £, ig through N, the, , , , , , , , , , *On passing throwgh the i+-platc, both circularly-polarised waves, become plne-pollerised perpendiculsr to each other. Hence, now on passing, rozating Nicol, they are aernately cut off with each 90° rotation, , through the, of the Nicol Ths shows that the waves emerging from the block are, cirowlarly-polarisee = opposite directions., , +The rotation produced by 2 liquid is considerably less than that proGoced by 2 crysal Therefore, the standard path length for a liquid is taken, | Gecimeter (10 can), instead of I mm as taken for crystals., , Optical Rotativa, , , , , , (Fig. 5), shade device H (called Laurent’s plate) and then through a tube D, containing the optically-active solution (say, sugar solution), and, , then falls on the analysing Nicol N, . The emergent is viewed, through atelescope 7. The analysing Nicol N, i rotated, about the light as axis, and its rotation can be measured on a, , circular degree-scale C by means of a vernier., Working—Let us suppose for a moment that the half-shade, device H is not present. The position of the Nicol ¥, is, so that the field of view is completely dark when the D, empty. In this position NV, is crossed with respect to, reading of N; is taken. Now the tube D is filled with the, mental solution. This rotates the plane of polarisation of the, coming from N, through some angle, say 8, so that some li is, transmitted by N,. Now N, is rotated until the field of view, again becomes dark and its reading is noted. This will happen, when N, has been rotated through the angle @ in the direction of, the optical rotation produced. Hence the difference of the two, readings of N, gives the rotation of the plane of polarisation., , Action of the Half-shade Device—The above method of, measuring the optical rotation is not accurate because the, cannot judge the position of complete darkness accurately. ., field appears dark over considerable range when Ny is rotated., Hence a pair of Nicols alone is not preferable in measuring optical, rotation., , The difficulty is avoided by, introducing a half-shade device, A immediately after the Nicol N, ‘It isa combination of two semicircular plates ACB and ADB, (Fig, 6). The plate ACB is of, quartz and is cut parallel to the § C|, optic axis, while the plate ADB is, of glass. The two are cemented, along the diameter AB. The, seek that invoduces «phase quan, , it introduces @, difference of = between the O and ig. 9), E vibrations, In other words, it ~ g r. :, isa half-wave plate. The thickness of the giass plate is such that, it absorbs the same amount of light as the quartz plate. =, , ze, =f, , eS, ?, , a, , 2Q Pp

Page 5 :

a Physical Optics, , The plane-polarised light from N, falls normally on the halfshade plate, Suppose this light has v: ions along OP (Fig. 6)., It is transmitted through glass-half as such and emerges with, vibrations still along OP. Inside the quartz-half, however, the light, is divided into two components, one E-component parallel to the, optic axis (04) of the quartz and the other O-component perpendicular to the optic axis, i.e. along OD. The O-component travels, faster in quartz. Therefore, on emergence, it gains a phase ofx, over the E-component. Hence now the O-component has vibrations along OC (instead of OD), the E-component still having, vibrations along OA. Therefore the light emerging from quartz, has resultant vibrations along OQ where / AOQ= / AOP., , , , , , , , (Fig. 7), , Now, if the principal section N,ON, of the analysing Nicol, N, is parallel to COD (Fig. 7a), both halves of the field appear, slightly but equally illuminated. This is because the components, OE and OF of the emergent vibrations OP and OQ along the, principal section of N, are small but equal. If N, is slightly rotated, from this position in the clockwise direction (Fig. 7b), the component OE appreciably decreases while OF appreciably increases., Hence the right-half of the field becomes darker and the left-half, brighter. Similarly, a slight rotation of N, in the anti-clockwise, direction (Fig. 7c) makes the right-half brighter and the left-half, darker. Our eye can judge far more accurately the position of, equal illumination of the two halves than the position of complete, darkness as is necessary in the absence of half-shade. Thus the, half-shade enables us to set-the analyser more accurately. A given, half-shade can, however, be used only for one particular wavelength for which it has been designed., , Determination of Specific Rotation of Sugar Solution—The ., , Nicol N, is first adjusted so that the two halves of the field are, , , , Optical Rotation 291, , slightly but equally illuminated (without the sugar solution). The, sina ofutiog i then placed between the half-shade and WN, , and, Ny, is adjusted so that once again the two halves of the field are, equally illuminated. In the second case, the solution rotates the, plane of vibration of OP and OQ through the same angle 6 (Fig. 8), in the same direction. Therefore, to obtain equally-illuminated, position again, the Nicol N, must be rotated through the angle @, in the direction of rotation produced. aA, , Hence the difference between the two positions of N, gives the angle of rotation 8., , The length Jof the tube containing jy,, , , , the solution is measured in decimeters. Cc, The specific rotation of the sugar solution, is then calculated from, cae f, = xe i, provided the concentration c of the solution (Fig. 8), , is known., , Determivation of the Strength of Sugar Solution—The polarimeter is, iltuminated by sodium light. The tube is kept empty and the analysing Nicol, is rotated till the intensities of the two halves of the field of view are equal., This position of the Nicol is noted on the circular scale. The given sugar, solutir then filled up in the tube, taking care that no air bubble remains, stuck init. The analysing Nicol is again rotated till the two halves of the, field are again equally illuminated. This position is also noted. The difference between the two readings gives the angle of rotation @ produced by the, sugar solution in the plane of polarisation of the light. The length of the, liquid colunn / in the tube is measured in decimeters. Lf m gm of sugar is, dissolved in w cm’ of an optically-inactive solvent (water), we have, , 6, S= Kxqmle) 2 fe, here S is the specific rota tion of the solution at the room temperature., Value is taken from the table of constants. Thus the strength of the solution, m é, (mje) is calculated from the fo: = SKE:, , This use of the polarimeter is important in commerce and industry for, eainniing is quantity of sugar in the presence ofan opticaliy-inactive, impurity. A polarimeter calibrated to read directly the percentage of canesugar in the solution is called as ‘saccharimeter’. ;, , 3. Explain the working of a biquartz-polarimeter. How, wate use if to find the specific seeaen e o, substance. (Meerut 87S, 86, Kanpur 89, ee 6 ae mas), , rate, Ans. Biquartz Polarimeter—It is @ simple and seas f determining the optical rotation of optically-active, fanaa ? It epated ioe a A Resins lens, a polarising Nicol, die