Page 2 :

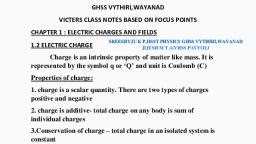

Chapter 2, Units and Measurement, The International System of Units, in 1971 the General Conference on Weights and Measures developed, Système Internationale d’ Unites (French for International System of Units),, abbreviated as SI system., In SI system there are seven base units and two supplementary units.

Page 3 :

Dimensional Formulae and Dimensional Equations

Page 12 :

Path Length (Distance Travelled), The total length of the path travelled by an object is called Path Length., It is a scalar quantity

Page 13 :

Displacement, Dispalcement is the change in position of the object., It is a vector quantity.

Page 23 :

Chapter 4, Motion in a Plane, Scalars and Vectors, A scalar quantity has only magnitude and no direction. It is specified, completely by a single number, along with the proper unit., Eg. distance ,mass , temperature, time ., A vector quantity has both magnitude and direction and obeys the, triangle law of addition or the parallelogram law of addition. A, vector is specified by giving its magnitude by a number and its, direction., Eg.displacement, velocity, acceleration and force., Representation of a Vector, A vector is representedby a bold letter say A or an arrow by an, arrow placed over a letter, say Ā ., The magnitude of a vector is called its absolute value, indicated by, |Ā|=A, Graphically a vector is represented by a line segment with an arrow, head., Q, Q is the head of the vector, Ā, R is the tail of the vector, P, The length of line segment gives the magnitude of the vector and, arrow mark gives its direction., Position and Displacement Vectors

Page 24 :

Let P and P′ be the positions of the object at time t and t′ ,, respectively ., OP is the position vector of the object at time t. OP = r., OP’ is the position vector of the object at time t’. OP’= r’, If the object moves from P to P′ , the vector PP′ is called the, displacement vector., Displacement vector is the straight line joining the initial and final, positions and does not depend on the actual path undertaken by the, object between the two positions., Equality of Vectors, Two vectors A and B are said to be equal if, and only if, they have the, same magnitude and the same direction., (a) Two equal vectors A and B., , (b) Two vectors A ′ and B ′ are unequal eventhough they are of, same length

Page 25 :

Projectile Motion, An object that is in flight after being thrown or projected is called a, projectile., , The components of initial velocity u are u cos θ along horizontal, direction and u sin θ along vertical direction., The x-component of velocity(u cos θ ) remains constant, throughout the motion and only the y- component(u sin θ ), changes. At the point of maximum height, v y = 0., Acceleration a x = 0 and a y = – g, Equation of path of a projectile, Displacement of the projectile after a time t, x = u cos θ t, 𝑥, , t =u cos θ, y = u sin θ t - ½ gt2, 𝑥, , 𝑥, , y = u sin θ (u cos θ)- ½ g(u cos θ)2, y = u tanθ x -, , g, x2, 2 (u cos θ)2, This equation is of the form y = a x + b x 2 , in which a and b are, constants. This is the equation of a parabola,, i.e. the path of the projectile is a parabola .

Page 26 :

Time of Flight of a projectile (T), , The total time T during which the projectile is in flight is called Time, of Flight, T., Consider the motion in vertical direction,, s = ut +½ at2, s=0,, u = u sin θ ,, a =-g ,, t=T, 0 = u sin θ T - ½ gT2, u sin θ T = ½ gT2, , T= 2 u sin θ, g

Page 27 :

Horizontal range of a projectile (R), The horizontal distance travelled by a projectile during its time of flight is, called the horizontal range, R., Horizontal range = Horizontal component of velocity x Time of flight, , R = u cos θ x 2 u sin θ, g, R = u2 2 sin θ cos θ, g, , R = u2 sin 2θ, g, R is maximum when sin2θ is maximum, i.e., when θ = 45 0 ., Rmax = u2, g, Show that for a given velocity of projection range will be same for angles 𝜽, and ( 90-𝜽 ), For angle θ, , R = u2 sin 2θ, g, , For angle (90 -θ), , R = u2 sin 2 (90 -θ), g, R = u2 sin (180 - 2θ), g, , Since sin (180 - 2θ) =sin 2θ, R = u2 sin 2θ, g, for a given velocity of projection range will be same for angles 𝜽 and ( 90-𝜽 )

Page 28 :

Maximum height of a projectile (H), It is the maximum height reached by the projectile., Consider the motion in vertical direction to the highest point, v2 – u2 = 2as, u = u sin θ, v = 0 , a = -g , s = H, 0 - u2 sin 2θ = -2 g H, , H = u2 sin 2θ, 2g, Example, A cricket ball is thrown at a speed of 28 m s –1 in a direction 30°, above the horizontal. Calculate (a) the maximum height, (b) the, time taken by the ball to return to the same level, and (c) the, distance from the thrower to the point where the ball, returns to the same level., (a) H = u2 sin 2θ, 2g, H = 282 sin2 30, 2 x 9.8, H = 10 m, (b) T = 2 u sin θ, g, T = 2x 28 sin30, 9.8, T = 2.9 s, (c) R = u2 sin 2θ, g, R = 282 sin60, 9.8, R = 69 m

Page 29 :

Chapter 5, Laws of Motion, Momentum, Momentum, P of a body is defined to be the product of its mass m, and velocity v, and is denoted by p., p=mv, Momentum is a vector quantity., Unit = kgm/s, [p] = ML 𝑇 −1, , Newton’s Second Law f Motion, , F=, , 𝐝𝐩, 𝐝𝐭, , Why a seasoned cricketer draws his hands backwards during, a catch?, By Newton's second law of motion ,, , F=, , 𝒅𝒑, 𝒅𝒕, , When he draws his hands backwards, the time interval (dt) to stop, the ball increases . Then force decreases and it does not hurt his, hands.

Page 30 :

Derivation of Equation of force from Newton's second law of, motion, By Newton's second law of motion ,, , For a body of ixed mass m, p=mv, = mv, dt, , F = ma, Force is a vector quantity, Unit of force is kgm, , ( ), , Definition of Newton, , Show that Newton’s second Law is consistent with the first law., , Zero acceleration implies the state of rest or uniform linear motion ., i.e, when there is no external force , the body will remain in its state

Page 31 :

of rest or of uniform motion in a straight line. This is Newtons first, law of motion., , Example, A bullet of mass 0.04 kg moving with a speed of 90 m/s enters a, heavy wooden block and is stopped after a distance of 60 cm. What, is the average resistive force exerted by the block on the bullet?

Page 32 :

Example

Page 33 :

Impulse (I), There are some situations where a large force acts for a very short, duration producing a finite change in momentum of the body. For, example, when a ball hits a wall and bounces back, the force on the, ball by the wall acts for a very short time when the two are in, contact, yet the force is large enough to reverse the momentum of, the ball., Impulse is the the product of force and time duration, which is the, change in momentum of the body., Impulse = Force × time duration, , I=Fxt, Unit = kgm𝑠 −1, [I] =MLT −1, , Impulsive force., A large force acting for a short time to produce a finite change in, momentum is called an impulsive force., , Impulse momentum Principle, Impulse is equal to the change in momentum of the body., By Newton's second law of motion,, 𝑑𝑝, , F= 𝑑𝑡, , F x dt = dp, I = dp, Impulse = change in momentum

Page 34 :

Example, A batsman hits back a ball straight in the direction of the bowler, without changing its initial speed of 12 m 𝑠 −1 . If the mass of the ball, is 0.15 kg, determine the impulse imparted to the ball., Impulse = change of momentum, Change in momentum = final momentum – initial momentum, Change in momentum = 0.15 × 12–(–0.15×12), Impulse = 3.6 N s, , Law of Conservation of Momentum, The total momentum of an isolated system of interacting particles, is conserved., Or, When there is no external force acting on a system of particles ,their, total momentum remains constant., , Proof of law of conservation of momentum, 𝑑𝑝, , By Newton's second law of motion , F= 𝑑𝑡, When F = 0, 𝑑𝑝, 𝑑𝑡, , =0, , dp = 0 ,, , p=constant, Thus when there is no external force acting on a system of particles,, their total momentum remains constant.

Page 35 :

Applications of law of conservation of linear momentum, 1.Recoil of gun, When a bullet is fired from a gun , the backward movement of gun is, called recoil of the gun., , If 𝐩𝐛 and 𝐩𝒈 are the momenta of the bullet and gun after firing, 𝐩𝐛 + 𝐩𝐠 = 0, 𝐩𝐛 = - 𝐩𝐠, The negative sign shows that gun recoils to conserve momentum., , Expression for Recoil velocity and muzzle velocity, Momentum of bullet after firing , 𝐩𝐛 = 𝐦𝐯, Recoil momentum of the gun after firing , 𝐩𝐠 = 𝐌𝐕, 𝐩𝐛 = - 𝐩 𝐠, 𝐦𝐯 = −𝐌𝐕, Recoil velocity of gun , V=, Muzzle velocity of bullet , v=, , −𝐦𝐯, 𝐌, −𝐌𝐕, 𝐦, , M= mass of gun, V= recoil velocity of bullet, m= mass of bullet, v=muzzle velocity of bullet

Page 36 :

2. The collision of two bodies, , Total Final momentum = Total initial momentum, i.e. , the total final momentum of the isolated system equals its total, initial momentum., , Friction, The force that opposes (impending or actual) relative motion, between two surfaces in contact is called frictional force., There are two types of friction-Static and Kinetic friction

Page 37 :

Static friction 𝐟𝐬, , • Static friction is the frictional force that acts between two surfaces in, contact before the actual relative motion starts. Or Static friction fs, opposes impending relative motion., The maximum value of static friction is ( fs )max, • The limiting value of static friction ( fs )max , is independent of the area, of contact., • The limiting value of static friction ( fs )max , varies with the normal, force(N), ( fs )max αN, ( 𝐟𝐬 )𝐦𝐚𝐱 = 𝛍𝐬 𝐍, Where the constant 𝛍𝐬 is called the coefficient of static friction and depends, only on the nature of the surfaces in contact., , The Law of Static Friction, The law of static friction may thus be written as , fs ≤ 𝛍𝐬 𝐍, 0r, ( 𝐟𝐬 )𝐦𝐚𝐱 = 𝛍𝐬 𝐍, Note:, If the applied force F exceeds ( fs )max , the body begins to slide on the, surface. When relative motion has started, the frictional force decreases, from the static maximum value ( fs )max, , Kinetic friction 𝐟𝐤

Page 38 :

Frictional force that opposes relative motion between surfaces in, contact is called kinetic or sliding friction and is denoted by fk . ., • Kinetic friction is independent of the area of contact., • Kinetic friction is nearly independent of the velocity., • Kinetic friction , fk varies with the normal force(N), fk αN, 𝐟𝐤 = 𝛍𝐤 𝐍, where μk the coefficient of kinetic friction, depends only on the, surfaces in contact., μk is less than μs, The Law of Kinetic Friction, 𝐟𝐤 = 𝛍𝐤 𝐍, where μk the coefficient of kinetic friction,, Example

Page 39 :

Body on an inclined surface, , The forces acting on a block of mass m When it just begins to slide, are, (i) the weight, mg, (ii) the normal force, N, (iii) the maximum static frictional force ( 𝐟𝐬 )𝐦𝐚𝐱, In equilibrium, the resultant of these forces must be zero., m g sin θ = ( fs )max ------------(1), m g cos θ = N-------------(2), But ( fs )max = μs N, Eqn (1) becomes, mg sin θ= μs N------------(3), (3), , mg sin θ, , Eqn(2) -------- m g cos θ =, , μs N, N, , 𝛍𝐬 = 𝐭𝐚𝐧 𝛉 ------------(4), 𝛉 = 𝐭𝐚𝐧−𝟏 𝛍𝐬, The equation (4) shows that the tangent of angle of friction is equal, to the coefficient of static friction., Angle of friction, The angle of an inclined plane with the horizontal ,at which the body placed, on it just begins to slide is called angle of friction.

Page 41 :

Applying second law to motion of the block, 30 – T = 3a ---------------(1), Apply the second law to motion of the trolley, T – fk = 20 a ------------(2), Nowfk = μk N,, Here μk = 0.04, N = 20 x 10 = 200 N., Substituting in eq(2), T – 0.04 x 200 = 20 a, T – 8 = 20a-------------(3), Solving eqns (1) and (3), 22, , a = 23m s−2 = 0.96 m s −2, T = 27.1 N, Rolling Friction, It is the frictional force that acts between the surfaces in contact, when one body rolls over the other., Rolling friction is much smaller than static or sliding friction., , Disadvantages of friction, friction is undesirable in many situations, like in a machine with, different moving parts, friction opposes relative motion and thereby, dissipates power in the form of heat, etc., Advantages of friction, In many practical situations friction is critically needed. Kinetic, friction is made use of by brakes in machines and automobiles. We, are able to walk because of static friction. It is impossible for a car, to move on a very slippery road. On an ordinary road, the friction, between the tyres and the road provides the necessary external, force to accelerate the car.

Page 42 :

Methods to reduce friction, (1)Lubricants are a way of reducing kinetic friction in a machine., (2)Another way is to use ball bearings between two moving parts of, a machine., (3) A thin cushion of air maintained between solid surfaces in, relative motion is another effective way of reducing friction., Circular Motion, The acceleration of a body moving in a circular path is directed, towards the centre and is called centripetal acceleration., , a=, , 𝐯𝟐, 𝐑, , The force f providing centripetal acceleration is called the, centripetal force and is directed towards the centre of the circle., 𝐟𝐬 =, , 𝐦𝐯 𝟐, 𝐑, , where m is the mass of the body, R is the radius of circle., For a stone rotated in a circle by a string, the centripetal force is, provided by the tension in the string., The centripetal force for motion of a planet around the sun is the, gravitational force on the planet due to the sun., Motion of a car on a curved level road

Page 43 :

Three forces act on the car., (i), The weight of the car, mg, (ii), Normal reaction, N, (iii), Frictional force, fs, As there is no acceleration in the vertical direction, N= mg, The static friction provides the centripetal acceleration, fs =, , mv2, R, , But , fs ≤ μs N, mv2, R, , ≤ μs mg, , (N=mg), , 𝐯 𝟐 ≤ 𝛍𝐬 𝐑𝐠, 𝐯𝐦𝐚𝐱 = √𝛍𝐬 𝐑𝐠, This is the maximum safe speed of the car on a circular level road., , Example, A cyclist speeding at 18 km/h on a level road takes a sharp circular, turn of radius 3 m without reducing the speed. The co-efficient of, static friction between the tyres and the road is 0.1. Will the cyclist, slip while taking the turn ?, v 2 ≤ μs R g, R = 3 m, g = 9.8 m s −2 , μs = 0.1., μs R g = 2.94 m2 s−2, v 2 ≤ 2.94 m2 s−2, Here v = 18 km/h = 5 m s −1, i.e., v 2 = 25 m2 s −2, The condition is not obeyed. The cyclist will slip while taking the, circular turn.

Page 45 :

If friction is absent, μs = 0, Then Optimum speed, 𝐯𝐨𝐩𝐭𝐢𝐦𝐮𝐦 = √𝐑𝐠 𝐭𝐚𝐧 𝛉, Example, A circular racetrack of ra dius 300 m is banked at an angle of 15°. If, the coefficient of friction between the wheels of a race-car and the, road is 0.2, what is the, (a) optimum speed of the racecar to avoid wear and tear on its, tyres, and, (b) maximum permissible speed to avoid slipping ?

Page 46 :

Chapter 6, Work , Energy and Power, Work, Consider a constant force F acting on an object of mass m. The object undergoes, a displacement d in the positive x-direction, , The work done by the force is defined to be the product of component of the, force in the direction of the displacement and the magnitude of this displacement., W = (F cos θ )d, W = Fd cos θ, , W = 𝐅⃗ ⋅ 𝐝⃗, Work can be zero, positive or negative., Zero Work, The work can be zero,if, (i)the displacement is zero ., When you push hard against a rigid brick wall, the force you exert on the, wall does no work., A weightlifter holding a 150 kg mass steadily on his shoulder for 30 s, does no work on the load during this time., (ii) the force is zero., A block moving on a smooth horizontal table is not acted upon by a, horizontal force (since there is no friction), but may undergo a large, displacement., (iii) the force and displacement are mutually perpendicular, Here θ = 90 o , cos (90) = 0., For the block moving on a smooth horizontal table, the gravitational, force mg does no work since it acts at right angles to the displacement., , Positive Work, If θ is between 0 o and 90 o , cos θ is positive and work positive., Eg: Workdone by Gravitational force on a freely falling body is positive

Page 47 :

Negative work, , If θ is between 90 o and 180 o , cos θ is negative and work negative., Eg: the frictional force opposes displacement and θ = 180 o ., Then the work done by friction is negative (cos 180 o = –1)., , Units of Work and Energy, Work and Energy are scalar quantities., Work and energy have the same dimensions, [ML 2 T –2 ]., The SI unit is kgm2s-2 or joule (J), named after the famous British physicist, James Prescott Joule., , Alternative Units of Work/Energy in J, , Example

Page 48 :

Kinetic Energy, The kinetic energy of an object is a measure of the work an object can do by the, virtue of its motion., If an object of mass m has velocity v, its kinetic energy K is, , Kinetic energy is a scalar quantity., , Example, In a ballistics demonstration a police officer fires a bullet of mass 50.0 g with, speed 200 m s-1 on soft plywood of thickness 2.00 cm. The bullet emerges with, only 10% of its initial kinetic energy. What is the emergent speed of the bullet ?, , Potential Energy, Potential energy is the ‘stored energy’ by virtue of the position or configuration, of a body., eg: A body at a height h above the surface of earth possesses potential, energy due to its position., A Stretched or compressed spring possesses potential energy due to its state, of strain., Gravitational Potential Energy of a body of mass m at a height h above the, surface of earth is mgh., Gravitational Potential Energy , V =mgh

Page 49 :

Show that the gravitational potential energy of the object at height h, is, equal to the kinetic energy of the object on reaching the ground. When the, object is released., PE at a height h,, , V = mgh, , When the object is released from a height it gains KE, K = ½ mv 2, v 2 = u2, , + 2as, u=0, a=g , s=h, v2 =, , 2gh, , K = ½ m x 2gh, K= mgh, Kinetic energy= Potential energy, , Conservative Force, A force is said to be conservative, if it can be derived from a scalar quantity., − 𝑑𝑉, 𝐹 = 𝑑𝑥 where V is a scalar, Eg: Gravitational force, Spring force., * The work done by a conservative force depends only upon initial and final, positions of the body, * The work done by a conservative force in a cyclic process is zero, Note: Frictional force , air resistance are non conservative forces., , The Conservation of Mechanical Energy, The principle of conservation of total mechanical energy can be stated as,, The total mechanical energy of a system is conserved if the forces, doing, work on it, are conservative.

Page 51 :

Graphical variation of KE and PE with height from ground, , Power, Power is defined as the time rate at which work is done or energy is transferred., The average power of a force is defined as the ratio of the work, W, to the total, time t taken., , 𝐏𝐚𝐯 =, , 𝐖, 𝐭, , The instantaneous power, The instantaneous power is defined as the limiting value of the average power as, time interval approaches zero., , P=, , 𝐝𝐖, 𝐝𝐭, , The work dW done by a force F for a displacement dr is dW = F. dr., P =F ., , dr, dt, , P= F.v, , where v is the instantaneous velocity when the force is F., *Power, like work and energy, is a scalar quantity., *Its dimensions are ML2T−3 ., *SI unit of power is called a watt (W). 1W = 1 J/s, *The unit of power is named after James Watt., *Another unit of power is the horse-power (hp), 1 hp = 746 W, This unit is still used to describe the output of automobiles, motorbikes, etc

Page 52 :

Electrical energy is measured in kilowatt hour (kWh)., 1kWh = 3.6 × 𝟏𝟎𝟔 J, , Note:, A 100 watt bulb which is on for 10 hours uses 1 kilowatt hour (kWh) of energy., Energy = Power x Time, =100 (watt) × 10 (hour), = 1000 watt hour =, =1 kilowatt hour (kWh), = 103 (W) × 3600 (s), = 3.6 × 𝟏𝟎𝟔 J, , Example, An elevator can carry a maximum load of 1800 kg (elevator + passengers) is, moving up with a constant speed of 2 m s–1. The frictional force opposing the, motion is 4000 N. Determine the minimum power delivered by the motor to the, elevator in watts as well as in horse power., The downward force on the elevator is F = m g + Frictional Force, = (1800 × 10) + 4000, = 22000 N, Power, P = F. v, = 22000 × 2, = 44000 W, In horse power, power = 44000/746, =59 hp

Page 53 :

Chapter 7, Systems of Particles and Rotational Motion, Angular Velocity and its Relation with Linear Velocity, , ⃗⃗⃗⃗ is directed along the fixed axis, The angular velocity is a vector quantity. 𝝎, as shown., The linear velocity of the particle is, , ⃗⃗⃗⃗, ⃗⃗⃗⃗ × 𝒓, ⃗⃗, 𝒗 =𝝎, ⃗⃗⃗⃗ and 𝒓, ⃗⃗ and is directed along the tangent to, It is perpendicular to both 𝝎, the circle described by the particle., , Figure shows the direction of angular velocity when the body rotates in, clockwise and anti clockwise direction., For rotation about a fixed axis, the direction of the vector ω does not change, with time. Its magnitude may change from instant to instant. For the more, general rotation, both the magnitude and the direction of ω may change, from instant to instant.

Page 54 :

Angular acceleration, Angular acceleration α, ⃗⃗ is defined as the time rate of change of angular, velocity., ⃗⃗⃗⃗, 𝒅𝝎, , ⃗⃗⃗ =, 𝜶, , 𝒅𝒕, If the axis of rotation is fixed, the direction of ω and hence, that of α is fixed., In this case the vector equation reduces to a scalar equation, , 𝛼=, , 𝑑𝜔, 𝑑𝑡, , Torque or Moment of Force, The rotational analogue of force is torque or moment of force ., , ⃗⃗⃗⃗acts on a single particle at a point P whose position with respect, If a force 𝐅, ⃗⃗ ,then torque about origin o is, to the origin O is 𝒓, ⃗⃗ = r F sinθ, 𝝉, , ⃗⃗ x ⃗⃗⃗⃗, ⃗𝝉⃗ = 𝒓, 𝐅, •, •, •, •, •, , Torque has dimensions M L2 T −2, Its dimensions are the same as those of work or energy., It is a very different physical quantity than work., Moment of a force is a vector, while work is a scalar., The SI unit of moment of force is Newton-metre (Nm)

Page 56 :

Relation connecting Torque and Angular momentum for a, system of particles, ⃗⃗, 𝒅𝑳, 𝒅𝒕, , ⃗⃗ =, 𝝉, , Where 𝐿⃗⃗ = 𝑙⃗1 + 𝑙⃗2 + ⋯ ⋅ +𝑙⃗𝑛, , Conservation of Angular momentum, For a system of particles, ⃗⃗, dL, , τ⃗⃗ext = dt, , If external torque, τ⃗⃗ext = 0 ,, ⃗⃗, dL, dt, , =0, , ⃗ = 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭, 𝐋, If the total external torque on a system of particles is zero, then the, total angular momentum of the system is conserved i.e, remains, constant., , Moment of Inertia, Moment of Inertia is the rotational analogue of mass., Moment of inertia is a measure of rotational inertia, , The moment of inertia of a particle of mass m rotating about an axis is, , I =m𝐫 𝟐

Page 57 :

The moment of inertia of a rigid body is, , The moment of inertia of a rigid body depends on the mass of the body, its, shape and size; distribution of mass about the axis of rotation, and the, position and orientation of the axis of rotation., , Moments of Inertia of some regular shaped bodies about, specific axes

Page 58 :

Rotational Kinetic energy, Cosider a particle of mass m rotating about an axis of radius r with angular, velocity 𝜔, The kinetic energy of motion of this particle is, 1, , 𝑘𝐸 = 2 𝑚𝑣 2, But v = r 𝜔, 1, , 𝑘𝐸 = 2 𝑚𝑟 2 𝜔2, , I =m𝑟 2, , 𝟏, , Rotational 𝐤𝐄 = 𝟐 𝐈𝛚𝟐, , Radius of Gyration (k), The radius of gyration can be defined as the distance of a mass point from, the axis of roatation whose mass is equal to the whole mass of the body and, whose moment of inertia is equal to moment of inertia of the whole body, about the axis., If K is the radius of gyration, we can write, I =M𝑘 2, 𝑰, , 𝒌=√, , 𝑴, , Flywheel, The machines, such as steam engine and the automobile engine, etc., that, produce rotational motion have a disc with a large moment of inertia, called, a flywheel. Because of its large moment of inertia, the flywheel resists the, sudden increase or decrease of the speed of the vehicle. It allows a gradual, change in the speed and prevents jerky motions, thereby ensuring a smooth, ride for the passengers on the vehicle.

Page 59 :

Theorems of Perpendicular and Parallel Axes, Perpendicular Axes Theorem, The moment of inertia of a planar body (lamina) about an axis, perpendicular to its plane is equal to the sum of its moments of inertia about, two perpendicular axes concurrent with perpendicular axis and lying in the, plane of the body., Or, The moment of inertia of a plane lamina about z axis is equal to the sum of, its moments of inertia about x-axis and y-axis, if the lamina lies in xy plane., , 𝐈𝐳 = 𝐈 𝐱 + 𝐈 𝐲, , (2) Parallel Axes Theorem, The moment of inertia of a body about any axis is equal to the sum of the, moment of inertia of the body about a parallel axis passing through its, centre of mass and the product of its mass and the square of the distance, between the two parallel axes., , 𝐈𝒛′ = 𝐈𝐳 + 𝐌𝒂𝟐

Page 62 :

Chapter 8, Gravitation, Universal Law of Gravitation, Every body in the universe attracts every other body with a force which is, directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely, proportional to the square of the distance between them, ., , 𝐅=𝐆, , 𝐦𝟏 𝐦𝟐, 𝐫𝟐, , where G is the universal gravitational constant., In vector Form, ⃗F⃗ = G m12m2 (−r̂) =−G m12m2 r̂, r, , r, , ̂r is the unit vector from m1 to m2 ., The gravitational force is attractive, as the force 𝐅⃗ is along – r., By Newton’s third law the, gravitational force ⃗F⃗12 on the body 1 due to 2, and ⃗F⃗21 on the body 2 due to 1 are related as ⃗F⃗12 = – ⃗F⃗21 ., The Gravitational Constant, The value of the gravitational constant G was determined experimentally by, English scientist Henry Cavendish in 1798., G = 6.67×1𝟎−𝟏𝟏 N 𝐦𝟐 /𝐤𝐠 𝟐, , Acceleration due to gravity of the Earth (g), The acceleration gained by a body due to the gravitational force of, earth is called acceleration due to gravity., Expression for g, Consider a body of mass m on the surface of earth of mass M and radius R., The gravitational force between body and earth is given by, F=, , GMm, R2, , -----------(1), , By Newton’s second law, F=mg, where g is acceleration due to gravity, g=, From Eq (1), , F, m, , 𝐆𝐌, , g=, , 𝐑𝟐

Page 63 :

Acceleration due to gravity is independent of mass of the body., The average value of g on the surface of earth is 9.8m𝐬 −𝟐 ., , Acceleration due to gravity below and above the surface of, earth, Acceleration due to gravity at a height h above the surface of the earth., Acceleration due to gravity on the surface, of earth, GM, , g=, , R2, , ------------(1), , Acceleration due to gravity at a height, above the surface of earth, gh =, , GM, (R+h)2, , ----------(2), , For , h << R, gh =, gh =, , GM, h, , R2 (1+R)2, GM, R2, , h, , (1 + )−2, R, , Substituting from eq(1), h, , g h = g(1 + )−2, R, , Using binomial expression and neglecting higher order terms., , 𝐠 𝐡 ≅ 𝐠 (𝟏 −, , 𝟐𝐡, 𝐑, , ), , Thus, as we go above earth’s surface, the acceleration due gravity, decreases by a factor (𝟏 −, , 𝟐𝐡, 𝐑, , )

Page 64 :

Acceleration due to gravity at a depth d below the surface of the earth, We assume that the entire earth is of uniform density. Then mass, of earth, Mass =volume x density, 4, M= πR3 ρ ------------(1), 3, , Acceleration due to gravity on the surface of, earth, g=, , GM, R2, , -------------(2), , Substituting the value of M in eq(2), g=, , G, , 4, , R, , 3, , 3, 2 ( πR ρ), , 4, , g = πRρG ---------------(3), 3, , Acceleration due to gravity at a depth d below the surface of earth, 4, g d = π(R − d)ρG ---------(4), 3, , eq(4), eq(3), , ------, , gd, g, gd, g, , =, =, , 4, π(R−d)ρG, 3, 4, πRρG, 3, , (R−d), R, , 𝐝, , 𝐠 𝐝 = 𝐠(𝟏 − 𝐑 ), Thus, as we go down below earth’s surface, the acceleration due gravity, decreases by a factor(𝟏 −, , 𝐝, 𝐑, , ), , The value of acceleration due to earth’s gravity is maximum on its surface, and decreases whether you go up or down., At the centre of earth acceleration due to earth’s gravity is zero.

Page 65 :

Chapter 9, Mechanical Properties of Solids, Stress and Strain, When a body is subjected to a deforming force, a restoring force is, developed in the body. This restoring force is equal in magnitude but, opposite in direction to the applied force., , Stress, The restoring force per unit area is known as stress., If F is the force applied and A is the area of cross section of the body,, 𝑭, , Stress =𝑨, , The SI unit of stress is N 𝑚−2 or pascal (Pa), Dimensional formula of stress is [ M𝐿−1 𝑇 −2 ], , Strain, Strain is defined as the fractional change in dimension., , Strain =, , 𝑪𝒉𝒂𝒏𝒈𝒆 𝒊𝒏 𝒅𝒊𝒎𝒆𝒏𝒔𝒊𝒐𝒏, 𝑶𝒓𝒊𝒈𝒊𝒏𝒂𝒍 𝒅𝒊𝒎𝒆𝒏𝒔𝒊𝒐𝒏, , Strain has no unit and dimension., , There are three ways in which a solid may change its dimensions when an, external force acts on it. As a result there are three types of stress and strain., 1. Longitudinal Stress, 2. Shearing Stress, 3. Hydraulic Stress, , and, and, and, , Longitudinal Strain, Shearing Strain, Hydraulic Strain (Volume Strain)

Page 66 :

1.Longitudinal Stress and Longitudinal Strain, , Longitudinal stress is defined as the restoring force per unit area when force, is applied normal to the cross-sectional area of a cylinder., Longitudinal stress=, , 𝑭, 𝑨, , If the cylinder is stretched the stress is called tensile stress and If the, cylinder is compressed it is called compressive stress., Longitudinal strain is defined as the ratio of change in length(ΔL) to original, length(L) of the body ., 𝐂𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐥𝐞𝐧𝐠𝐭𝐡, , Longitudinal strain = 𝐎𝐫𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐥𝐞𝐧𝐠𝐭𝐡, Longitudinal strain =, , 𝚫𝐋, 𝑳, , 2.Shearing Stress and Shearing Strain, , Shearing stress is defined as the restoring force per unit area when a, tangential force is applied on the cylinder., 𝑭, , Shearing stress=𝑨, Shearing strain is defined as the ratio of relative displacement of the faces, Δx to the length of the cylinder L, , Shearing strain =, , 𝚫𝐱, 𝑳, , =tanθ, Usually θ is very small, tan θ ≈ θ, , Shearing strain = θ

Page 67 :

3.Hydraulic Stress and Hydraulic strain (Volume Strain), , When a solid sphere placed in the fluid, the force applied by the fluid acts in, perpendicular direction at each point of the surface., The restoring force per unit area of solid sphere, placed in the fluid is called, hydraulic stress., 𝐅, , Hydraulic stress= = -P (pressure), 𝐀, , The negative sign indicates that when pressure increases, the volume decreases., , Volume strain(hydraulic strain) is defined as the ratio of change in volume, (ΔV) to the original volume (V)., Volume strain=, , 𝐂𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐯𝐨𝐥𝐮𝐦𝐞, , Volume strain=, , 𝐎𝐫𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐯𝐨𝐥𝐮𝐦𝐞, , 𝚫𝐕, 𝐕, , Hooke’s Law, For small deformations the stress is directly proportional to strain. This is, known as Hooke’s law., Stress ∝ Strain, stress = k × strain, 𝐒𝐭𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐬, 𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐢𝐧, , =𝒌, , where k is the proportionality constant and is known as, Modulus of Elasticity., The SI unit of modulus of elasticity is N 𝑚−2 or pascal (Pa), (same as that of stress,since strain is unitless), , Dimensional formula is [ M𝐿−1 𝑇 −2 ]

Page 68 :

Stress-Strain Curve, A typical stress-strain curve for a metal is as shown in figure:, , In the region from O to A, The curve is linear. In this region, stress is proportional to strain i.e, Hooke’s, law is obeyed., In the region from A to B, Stress and strain are not proportional, i.e, Hooke’s law is not obeyed., Nevertheless, the body is still elastic., The point B in the curve is known as yield point or elastic limit., The stress corresponding to yield point is known as yield strength (𝑺𝒚 ) of, the material., , In the region from B to D, Beyond the point B ,the strain increases rapidly even for a small change in, the stress. When the load is removed, at some point C between B and D, the, body does not regain its original dimension. The material is said to have a, permanent set. The material shows plastic behaviour in this region., The point D on the graph is the ultimate tensile strength (𝑺𝒖 ) of the, material.

Page 69 :

In the region from D to E, Beyond this point D, additional strain is produced even by a reduced applied, force and fracture occurs at point E., The point E is called Fracture Point., If the ultimate strength and fracture points D and E are close, the material is, said to be brittle., If D and E are far apart, the material is said to be ductile., , Elastomers, Substances like tissue of aorta, rubber etc. which can be stretched to cause, large strains are called elastomers., Example-2, The stress-strain graphs for materials A and B are shown in Figure., , The graphs are drawn to the same scale., (a) Which of the materials is more elastic?, (b) Which of the two is the stronger material?, (c) Which of the two materials is more ductile?, stress, (a), modulus of elasticity =, = slpoe of the graph., strain, , Slope of graph for material A is greater than that of B., So material A is more elstic than B, (b) Strength of a material is determined by the amount of stress, required to cause fracture., The fracture point is greater for material A., So material A is stronger than B, (c) The fracture point is far apart for material A than B., So material A is more ductile than B.

Page 70 :

Chapter 10, Mechanical Properties Of Fluids, Pascal’s law for transmission of fluid pressure, Whenever external pressure is applied on any part of a fluid contained in a, vessel, it is transmitted undiminished and equally in all directions., , Applications of Pascal’s law, 1.Hydraulic lift, , The pressure on smaller piston, P=, , F1, A1, , --------------(1), , This pressure is transmitted to the larger cylinder with a larger piston of, area A2 ., Upward force on A2 ,, F2 = P A2, Substituting from eq(1),, , F2 =, , F1, A1, , 𝐅𝟐 = 𝐅𝟏, , A2, 𝐀𝟐, 𝐀𝟏, , Thus, the applied force has been increased by a factor of, , A2, A1, , and this factor is, , the mechanical advantage of the device., , Problem, Two syringes of different cross sections (without needles) filled with water, are connected with a tightly fitted rubber tube filled with water. Diameters, of the smaller piston and larger piston are 1.0 cm and 3.0 cm respectively., (a) Find the force exerted on the larger piston when a force of 10 N is, applied to the smaller piston. (b) If the smaller piston is pushed in through, 6.0 cm, how much does the larger piston move out?

Page 71 :

F2 = F1, , A2, A1, , π x (1.5 x 10−2 )2, F2 = 10 x, π x (0.5 x 10−2 )2, = 10 x9, =90 N, (b) Volume covered by the smaller piston is equal to volume moved by the, larger piston., L1 A1 = L2 A2, L2 = L1, , A1, A2, 2, , = 6 x10, , −2, , x, , π x (0.5 x 10−2 ), , π x (1.5 x 10−2 )2, , =0.54m, , = 6 x10−2 x0.111, = 0.67 x10−2 m, = 0.67cm, , Problem, In a car lift compressed air exerts a force F1 on a small piston having a, radius of 5.0 cm. This pressure is transmitted to a second piston of radius 15, cm . If the mass of the car to be lifted is 1350 kg, calculate F1 . What is the, pressure necessary to accomplish this task? (g = 9.8 ms −2 )., A1, , F1 = F2 (, , A2, , ), F2 = mg = 1350 x 9.8, =13230N, 2, , F1 = 13230 x, = 13230 x, , π x (5 x 10−2 ), , πx (15 x 10−2 )2, 25, 225, , =1470 N, The air pressure that will produce this force is, P=, P=, , F1, A1, , 1470, 3⋅14 x (5 x 10−2 )2, , =1.9 x105 Pa

Page 72 :

2.Hydraulic brakes, When we apply a force on the pedal with our foot the master piston moves, inside the master cylinder, and the pressure caused is transmitted through, the brake oil to act on a piston of larger area. A large force acts on the piston, and is pushed down expanding the brake shoes against brake lining. In this, way a small force on the pedal produces a large retarding force on the wheel., The pressure set up by pressing pedal is transmitted equally to all cylinders, attached to the four wheels so that the braking effort is equal on all wheels., , Bernoulli’s Principle, Bernoulli’s principle states that as we move along a streamline, the sum of, the pressure , the kinetic energy per unit volume and the potential energy, per unit volume remains a constant., 𝟏, , 𝐏 + 𝛒𝐯 𝟐 + 𝛒𝐠𝐡= constant, 𝟐, , The equation is basically the conservation of energy applied to non viscous, ,incompressible fluid motion in steady state., , Proof of Bernoulli’s Principle, , Consider the flow of an ideal fluid in a pipe of varying cross section. The fluid, in a section of length v2 Δt moves to the section of length v1 Δt in time Δt., The work done on the fluid at left end (BC) is

Page 75 :

Chapter 11, Thermal Properties of Matter, Thermal Expansion, The increase in the dimensions of a body due to the increase in its, temperature is called thermal expansion., Three types of thermal expansions are, 1.Linear expansion, 2.Area expansion, 3.Volume expansion, , 1.Linear Expansion, The expansion in length is called linear expansion., , If the substance is in the form of a long rod,, The fractional change in length,, , 𝛥𝑙, 𝑙, 𝛥𝑙, 𝑙, , ∝ ΔT., = 𝛼𝑙 ΔT, , 𝜶𝒍 =, , 𝚫𝐥, 𝒍 𝚫𝐓, , where 𝛼𝑙 is known as the coefficient of linear expansion and is characteristic, of the material of the rod., • Metals expand more and have relatively high values of αl ., • Copper expands about five times more than glass for the same rise in, temperature.

Page 78 :

Thermal Expansion of Water(Or) Anomalous Behavour of Water, , Water exhibits an anomalous behavour; it contracts on heating from 0 °C to, 4 °C. When it is heated after 4 °C ,it expands like other liquids. This means, that water has minimum volume and hence maximum density at 4 °C ., , Why the bodies of water, such as lakes and ponds, freeze at the top, first?, This is due to anomalous expansion of water. water has minimum volume, and hence maximum density at 4 °C ., As a lake cools toward 4 °C, water near the surface becomes denser, and, sinks. Then the warmer, less dense water near the bottom rises. When this, layer cools below 4 °C, it freezes, and being less dense, remain at the, surfaces. Thus water bodies freeze at the top first. Water at the bottom, protects aquatic animal and plant life., , The coefficient of volume expansion at constant pressure for an ideal gas, The ideal gas equation,, At constant pressure,, , PV = μRT ------------------(1), PΔV = μR ΔT, ΔV, V, , =, , μR ΔT, PV, , From eq(1),, ΔV, V, , =, , ΔT, T, , μR, PV, , =, , 1, T

Page 79 :

ΔV, , 1, , =T, VΔT, , 𝛂𝐯 =, , 𝟏, 𝐓, , ( for an ideal gas at constant pressure), , Thermal Stress, If the thermal expansion of a rod is prevented by fixing its ends rigidly, the, rod acquires a compressive strain. The corresponding stress set up in the, rod is called thermal stress., , Change of State, Matter normally exists in three states: solid, liquid, and gas., A transition from one of these states to another is called a change of state., The temperature of the system does not change during change of state., , Change of state from solid to liquid, The change of state from solid to liquid is called melting and from liquid to, solid is called fusion., Both the solid and liquid states of the substance coexist in thermal, equilibrium during the change of states from solid to liquid., The temperature at which the solid and the liquid states of the substance in, thermal equilibrium with each other is called its melting point., Melting point decrease with increase in pressure . The melting point of a, substance at standard atomspheric pressure is called its normal melting, point., , Regelation

Page 80 :

When the wire passes through the ice slab , ice melts at lower temperature, due to increase in pressure. When the wire has passed, water above the wire, freezes again. This phenomenon of refreezing is called regelation., , Skating is possible on snow due to the formation of water below the skates., Water is formed due to the increase of pressure and it acts as a lubricant., , The change of state from liquid to vapour, The change of state from liquid to vapour (or gas) is called vaporisation and, from vapour to liquid is called condensation., The temperature remains constant until the entire amount of the liquid is, converted into vapour, The temperature at which the liquid and the vapour states of the substance, coexist in thermal equilibrium is called its boiling point., The boiling point increases with increase in pressure and decreases with, decreases in pressure. The boiling point of a substance at standard, atmospheric pressure is called its normal boiling point., • Cooking is difficult on hills. At high altitudes, atmospheric pressure is, lower, boiling point of water decreases as compared to that at sea, level., • Boiling point is increased inside a pressure cooker by increasing the, pressure. Hence cooking is faster., , A plot of temperature versus time showing the changes in the state, of ice on heating.

Page 81 :

Sublimation, The change from solid state to vapour state without passing through the, liquid state is called sublimation, and the substance is said to sublime., Eg: Dry ice (solid CO2) , Iodine., During the sublimation process both the solid and vapour states of a, substance coexist in thermal equilibrium., , Change of state, Solid to Liquid, Liquid to Solid, Liquid to Gas, Gas to Liquid, Solid to Gas, , Melting, Fusion, Vaporisation, Condensation, Sublimation, , Latent Heat, The amount of heat per unit mass transferred during change of state of the, substance is called latent heat of the substance for the process., The heat required during a change of state depends upon the heat of, transformation and the mass of the substance undergoing a change of state., Q =mL, , L=, , 𝐐, 𝐦, , where L is known as latent heat and is a characteristic of the substance., SI unit of Latent Heat is J k𝑔−1, The value of L also depends on the pressure. Its value is usually quoted at, standard atmospheric pressure, , Latent Heat of Fusion (𝐋𝐟 ), The latent heat for a solid -liquid state change is called the latent heat of, fusion (𝐋𝐟 ) or simply heat of fusion., , Latent Heat of Vaporisation (𝐋𝐯 ), The latent heat for a liquid-gas state change is called the latent heat of, vaporisation (𝐋𝐯 ) or heat of vaporisation.

Page 82 :

Temperature versus heat for water at 1 atm pressure (not to scale)., , • The slopes of the phase lines are not same, which indicate that specific, heats of the various states are not equal. The specific heat capacity of, water is greater than that of ice., ΔQ = m s ΔT, The amount of heat required ,ΔQ in liquid phase will be greater than, that in solid phase for same ΔT., So slope of liquid phase is less than that of solid phase., • For water, the latent heat of fusion is 𝐋𝐟 = 3.33 × 105 J k𝑔−1 ., That is 3.33 × 105 J of heat are needed to melt 1 kg of ice at 0 °C., For water, the latent heat of vaporisation is 𝐋𝐯 = 22.6 × 105 J k𝑔−1 ., That is 22.6 × 105 J of heat is needed to convert 1 kg of water to steam, at 100 °C., , Why burns from steam are usually more serious than those from, boiling water?, For water, the latent heat of vaporisation is 𝐋𝐯 = 22.6 × 105 J k𝑔−1 ., That is 22.6 × 105 J of heat is needed to convert 1 kg of water to steam at, 100 °C. So, steam at 100 °C carries 22.6 × 105 J k𝑔−1 more heat than water, at 100 °C. This is why burns from steam are usually more serious than those, from boiling water.

Page 83 :

Example, When 0.15 kg of ice at 0 °C is mixed with 0.30 kg of water at 50°C in a, container, the resulting temperature is 6.7 °C. Calculate the heat of fusion of, ice. (𝑠𝑤𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑟 = 4186 J k𝑔−1 𝐾 −1 ), ΔQ = m s ΔT, Heat lost by water = m𝑠𝑤𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑟 (T𝑓 –T𝑖 ), = 0.30 x 4186 x (50.0 °C – 6.7 °C), = 54376.14 J, Heat required to melt ice = m L𝑓, = (0.15 kg) L𝑓, Heat required to raise temperature of ice water to final temperature, = m 𝑠𝑤𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑟 (T𝑓 –T𝑖 ), = 0.15 x 4186 x(6.7 °C – 0 °C), = 4206.93 J, , Heat lost = heat gained, 54376.14 J = (0.15 kg) L𝑓 + 4206.93 J, 𝐋𝒇 = 3.34×105 J k𝒈−𝟏

Page 84 :

Chapter 12, Thermodynamics, First Law of Thermodynamics, The heat supplied to the system is partly used to increase the internal, energy of the system and the rest is used to do work on the environment ., , ΔQ = ΔU + ΔW, ΔQ = Heat supplied to the system by the surroundings, ΔW = Work done by the system on the surroundings, ΔU = Change in internal energy of the system, • If work is done by the system against a constant pressure P ,then, ΔW = P ΔV, , (ΔW=F Δx, =PA Δx, =P ΔV), , ΔQ = ΔU + P ΔV, • If a system is taken through a process in which ΔU = 0, ΔQ = ΔW, Heat supplied to the system is used up entirely by the system in doing, work on the environment., Eg: Isothermal expansion of an ideal gas, • From the First Law of Thermodynamics,, ΔQ - ΔW = ΔU, As ΔU is path independent ( ΔQ - ΔW )should also be path independent., i.e., eventhough ΔQ and ΔW are path dependent, their combination, ΔQ – ΔW, is path independent., , Thermodynamic Process, A thermodynamic process is defined as a change from one equilibrium state, to another.

Page 85 :

Quasi-static process, The name quasi-static means nearly static., A quasi-static process is an infinitely slow process such that the system, remains in thermal and mechanical equilibrium with the surroundings, throughout., In a quasi-static process, the pressure and temperature of the environment, can differ from those of the system only infinitesimally., Eg: Processes that are sufficiently slow and do not involve accelerated, motion of the piston, large temperature gradient, etc. are reasonably, approximation to an ideal quasi-static process., , Some special thermodynamic processes, , Isothermal process., A process in which the temperature of the system is kept fixed throughout is, called an isothermal process., For isothermal process T = constant ., So internal energy does not change, ΔU=0, • Eg: Change of state (Melting, fusion, vaporistion..), • The expansion of a gas in a metallic cylinder placed in a large reservoir, of fixed temperature is an example of an isothermal process., , Equation of state for an isothermal process, For an ideal gas,, , PV=μRT, , If an ideal gas goes isothermally from its initial state to the final state , its, temperature remains constant, , PV = constant, This is the equation of state for an isothermal process.

Page 89 :

First law of thermodynamics for an isochoric process, Δ Q= ΔU+ ΔW, For isochoric process, Δ W =0, Δ Q= ΔU, The heat absorbed by the gas goes entirely to change its internal energy and, thereby its temperature., , Isobaric Process, In an isobaric process, P is constant., , Work done by the gas in an Isobaric process, Work done by the gas is, Δ W=P ΔV, W = P (𝐕𝟐 − 𝐕𝟏 ), W= μ R (𝐓𝟐 − 𝐓𝟏 ), , First Law of Thermodynamics for an Isobaric Process, Since temperature changes, internal energy also changes. The heat, absorbed goes partly to increase internal energy and partly to do work., Δ Q= ΔU+ ΔW, , Cyclic Process, In a cyclic process, the system returns to its initial state., Since internal energy is a state variable, ΔU = 0 for a cyclic process, First Law of Thermodynamics for Cyclic Process, Δ Q= ΔU+ ΔW, ΔU = 0, Δ Q= ΔW, The total heat absorbed equals the work done by the system.

Page 90 :

P-V curves for isothermal and adiabatic processes of an ideal gas., , Heat Engines, Heat engines convert heat energy into mechanical energy., Heat engine is a device by which a system is made to undergo a cyclic, process that results in conversion of heat to work., , Heat engines consists of :, (1) Working substance–the system., Eg:A mixture of fuel vapour and air in a gasoline or diesel engine or, steam in a steam engine are the working substances., (2) An external reservoir at some high temperature T1 called source, (3) An external reservoir at some lower temperature T2 called sink., , The working substance absorbs a total amount of heat Q1 from the source, at higher temperature, some external work is done by it on the environment, and releases remaining amount of heat Q 2 to the sink at lower, temperature T2 ., Q1 = W + Q 2, , W =𝐐𝟏 − 𝐐𝟐

Page 91 :

Efficiency of heat engine(η), The efficiency (η) of a heat engine is defined by, , 𝛈=, , 𝐰, , 𝐐𝟏, , where Q1 is the heat absorbed by the system from the source in one, complete cycle, W is the work done by the system on the environment in a cycle., W =𝐐𝟏 − 𝐐𝟐, , 𝛈=, , 𝐐𝟏 − 𝐐𝟐, 𝐐𝟏, , 𝐐, , 𝛈 = 𝟏 − 𝐐𝟐, 𝟏, , For Q2 = 0, η = 1,, i.e., the engine will have 100% efficiency in converting heat into work., Such an ideal engine with η = 1 (100% efficiency) is never possible, even if, we can eliminate various kinds of losses associated with actual heat engines., A fundamental limit on the efficiency of a heat engine is set by an, independent principle of nature, called the Second Law of Thermodynamics, , External and Internal combustion engines, The mechanism of conversion of heat into work varies for different heat, engines. Basically, there are two types of heat engines: External combustion, engines and Internal combustion engines, , External Combustion Engine, In an external combustion engine, the system is heated by an external, furnace., Eg: steam engine, , Internal Combustion Engines, In an internal combustion engine, the system is heated internally by an, exothermic chemical reaction., Eg: Petrol engine ,Diesel engine.

Page 92 :

Chapter 13, Kinetic Theory, Kinetic Theory of an Ideal Gas, • A given amount of gas is a collection of a large number of molecules, that are in random motion., • At ordinary pressure and temperature, the average distance between, molecules is very large compared to the size of a molecule (2 Å)., • The interaction between the molecules is negligible., • The molecules make elastic collisions with each other and also with, the walls of the container ., • As the collisions are elastic , total kinetic energy and total momentum, are conserved ., • The average kinetic energy of a molecule is proportional to the, absolute temperature of the gas., , Pressure of an Ideal Gas, , A gas is enclosed in a cube of side 𝑙, Consider a molecule moving in positive x direction makes an elastic collision, with the wall of thecontainer., Momentum before collision = mvx, Momentum after collision = −mvx, The change in momentum of the molecule = −mvx −mvx, = −2 mvx, By the principle of conservation of momentum, , Momentum imparted to wall in the collision = 2mvx

Page 94 :

Kinetic Interpretation of Temperature, 1, P= nmv̅̅̅2, 3, , 1, PV= nVmv̅̅̅2, 3, , N, , n= , N=nV, V, , 1, PV= Nmv̅̅̅2, 3, , where N is the number of molecules in the sample., PV=, , 2, 3, , (N, , 1, 2, , mv̅̅̅2 ), , The quantity in bracket is the average translational kinetic energy of the, molecules in the gas., 1, N mv̅̅̅2 =E, 2, , PV=, , 2, 3, , E---------------------(1), , Ideal gas equation, PV =Nk B T -------------------(2), From eq(1)and (2), , 2, 3, , E = Nk B T, 3, , E = Nk B T, 2, , 𝟑, , E/N = 𝟐 𝐤 𝐁 T, The average kinetic energy of a molecule is proportional to the absolute, temperature of the gas; it is independent of pressure, volume or the nature, of the ideal gas., , Note:, This is a fundamental result relating temperature( a macroscopic, measurable parameter) to the average kinetic energy(microscopic, quantity) of a gas molecule. The two domains are connected by the, Boltzmann constant.

Page 96 :

Chapter 14, Oscillations, Simple Harmonic Motion, Simple harmonic motion is the simplest form of oscillatory motion., Simple harmonic motion is the motion executed by a particle subject to a, force, which is proportional to the displacement of the particle and is, directed towards the mean position., , Mathematical expression for an SHM, , Consider a particle vibrating back and forth about the origin of x-axis,, between the limits +A and –A., If the motion is simple harmonic ,its position can be represented as a, function of time., , x (t) = A cos (ωt + 𝛟), , Phase, The time varying quantity, (ωt + ϕ), is called the phase of the motion., It describes the state of motion at a given time., , Phase Constant, The constant ϕ is called the phase constant (or phase angle). The value, of ϕ depends on the displacement and velocity of the particle at t = 0., The phase constant signifies the initial conditions.

Page 97 :

A plot of displacement as a function of time for ϕ = 0., x (t) = A cos (ωt ), , The curve 3 , for ϕ = 0 ,, x (t) = A cos (ωt ), The curve 4 , for ϕ = -π/4 , x (t) = A cos (ωt - π/4), The amplitude A is same for both the plots, , The Simple Pendulum, , A simple pendulum consists of a particle of mass m ( bob ) suspended from, one end of an unstretchable, massless string of length L fixed at the other, end.

Page 101 :

The speed of a wave is related to its wavelength and frequency , but it is, determined by the properties of the medium., , Speed of a Transverse Wave on Stretched String, The speed of transverse waves on a string is determined by two factors,, (i) the linear mass density or mass per unit length, μ, and, (ii) (ii) the tension T, 𝑻, , v=√𝛍, , The speed of a wave along a stretched ideal string does not depend on the, frequency of the wave., , Example, A steel wire 0.72 m long has a mass of 5.0 ×10−3 kg. If the wire is under a, tension of 60 N, what is the speed of transverse waves on the wire ?, 𝑇, , v=√μ, μ=, =, , 𝑀, 𝑙, , 5.0 ×10−3, 0.72, , = 6.9 ×10−3 kg 𝑚−1, T = 60 N, , v=√, , 60, 6.9 ×10−3, , v= 93 m 𝑠 −1

Page 102 :

Speed of a Longitudinal Wave Speed of Sound, The longitudinal waves in a medium travel in the form of compressions and, rarefactions or changes in density, ρ., • The speed of propagation of a longitudinal wave in a fluid, 𝑩, , v=√ 𝛒, , B= the bulk modulus of medium, ρ = the density of the medium, , • The speed of a longitudinal wave in a solid bar, 𝒀, , v=√𝛒, , Y =Young’s modulus, ρ=density of the medium,, , • The speed of a longitudinal wave in an ideal gas, Case1 -Newtons Formula, Newton assumed that, the pressure variations in a medium during, propagation of sound are isothermal., For isothermal process, PV = constant, VΔP + PΔV = 0, −VΔP, ΔV, , =P, , B =P, 𝑷, , v=√, , ρ, , This relation was first given by Newton and is known as Newton’s formula.