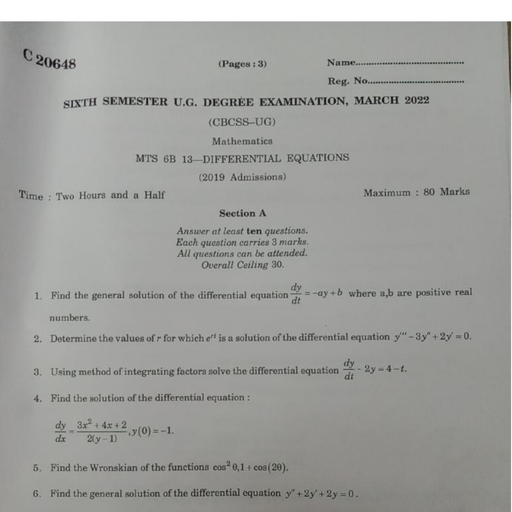

Page 1 :

1268, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , 38. Evaluate 兰C (3x 2y � e y) dx � (x 3 � xe y � 2y) dy, where C, is the curve of Exercise 37., , 42. Let, F(x, y, z) �, , 39. Let, E(x, y, z) �, , kQ, r, 冟 r 冟3, , x � y2, , i�, , 44. If F is a nonconservative vector field, then 兰C F ⴢ dr � 0, whenever C is a closed path., 45. If F has continuous first-order partial derivatives in space, and C is any smooth curve, then 兰C §f ⴢ dr depends only, on the endpoints of C., , x, x 2 � y2, , j, , 46. If F � Pi � Q j is in an open connected region R and, �Q, �P, for all (x, y) in R, then 兰C F ⴢ dr � 0 for any, �, �x, �y, smooth curve C in R., , �Q, �P, a. Show that, ., �, �x, �y, b. Show that 兰C F ⴢ dr is not independent of path by computing 兰C1 F ⴢ dr and 兰C2 F ⴢ dr, where C1 and C2 are, the upper and lower semicircles of radius 1, centered at, the origin, from (1, 0) to (�1, 0)., c. Do your results contradict Theorem 5? Explain., , 15.5, , 47. If F(x, y) is continuous and C is a smooth curve, then, 兰C F ⴢ dr � � 兰�C F ⴢ dr., 48. If F has first-order partial derivatives in a simply-connected, region R, then 兰C F ⴢ dr � 0 for every closed path in R., , Green’s Theorem, , y, , Green’s Theorem for Simple Regions, R, , C, , x, , 0, , FIGURE 1, A plane region R bounded by a simple, closed plane curve C, y, , Green’s Theorem, named after the English mathematical physicist George Green (1793–, 1841), relates a line integral around a simple closed plane curve C to a double integral, over the plane region R bounded by C. (See Figure 1.), Before stating Green’s Theorem, however, we need to explain what is meant by the, orientation of a simple closed curve. Suppose that C is defined by the vector function, r(t), where a t b. Then C is traversed in the positive or counterclockwise direction if the region R is always on the left as the terminal point of r(t) traces the boundary curve C. (See Figure 2.), , THEOREM 1 Green’s Theorem, C, , Let C be a piecewise-smooth, simple closed curve that bounds a region R in the, plane. If P and Q have continuous partial derivatives on an open set that contains R, then, , R, , �Q, , �P, , 冯 P dx � Q dy � 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA, , r(t), , C, , 0, , k, , 43. The region R � {(x, y) 冟 0 � x 2 � y 2 � 1} is simplyconnected., , 41. Let, y, , z, (y 2 � z 2)2, , In Exercises 43–48, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why. If it is false, explain why or give, an example that shows it is false., , 40. Find the work that is done by the force field, F(x, y, z) � y 2zi � 2xyz j � xy 2k on a particle moving along, a path from P(1, 1, 1) to Q(2, 1, 3) ., , 2, , j�, , a. Show that curl F � 0., b. Is F conservative? Explain., , where k is a constant, and let r � xi � yj � zk be the electric field induced by a charge Q located at the origin. (See, Example 4 in Section 15.1.) Find the work done by E in, moving a charge of q coulombs from the point A(1, 3, 2), along any path to the point B(2, 4, 1)., , F(x, y) �, , y, (y 2 � z 2)2, , x, , FIGURE 2, The curve C traversed in the positive or, counterclockwise direction, , (1), , R, , where the line integral over C is taken in the positive (counterclockwise) direction.

Page 2 :

15.5, , Note, , Historical Biography, , 冯 P dx � Q dy, , (1793–1841), , 冯, , or, , P dx � Q dy, , C, , C, , is sometimes used to indicate that the line integral over a simple closed curved C is, taken in the positive, or counterclockwise, direction., , Born a miller’s son in Nottingham, George, Green worked in his father’s grain mill for, most of the first forty years of his life. He, did receive some formal schooling when he, was 8 to 9 years old, but Nottingham had, limited educational resources, and Green, quickly surpassed the education that was, available there. He studied on his own,, though it is not quite clear how he got, access to the current mathematical works., However, in 1828 Green published “An Essay, on the Application of Mathematical Analysis to the Theories of Electricity and Magnetism.” This work included the theorem, that is now known as Green’s Theorem. The, essay was sold to only 51 people, many of, whom are believed to have been friends of, Green’s, who probably did not understand, the importance of the work. Eventually,, Green’s talents were recognized by, acquaintances who were more connected, to academia, and he enrolled as an undergraduate at Cambridge in 1833 at the age, of 40. Green graduated in 1837 with the, fourth highest scores in his class. He, stayed on at Caius College, Cambridge and, was elected a fellow in 1839. During his, time at Cambridge he made significant, contributions to areas such as optics,, acoustics, and hydrodynamics. Green’s, health was poor, and he died in Nottingham in1841. Because of the limited contact, he had with his scientific contemporaries,, most of Green’s work was not appreciated, during his lifetime., , Since it is not easy to prove Green’s Theorem for general regions, we will prove it, only for the special case in which the region R is both a y-simple and an x-simple, region. (See Section 14.2.) Such regions are called simple or elementary regions., , PROOF OF GREEN’S THEOREM FOR SIMPLE REGIONS Let R be a simple region with, boundary C as shown in Figure 3. Since, , 冯 P dx � Q dy � 冯 P dx � 冯 Q dy, C, , C, , C, , we can consider each integral on the right separately. Since R is a y-simple region, it, can be described as, R � {(x, y) 冟 a, , x, , b, f1(x), , y, , f2 (x)}, , where f1 and f2 are continuous on [a, b]. Observe that the boundary C of R consists of, the curves C1 and C2 that are the graphs of the functions f1 and f2 as shown in the figure. Therefore,, , 冯 P dx � 冮, C, , P dx �, , C1, , 冮, , P dx, , C2, , where C1 and C2 are oriented as shown in Figure 3., Observe that the point (x, f1(x)) traces C1 as x increases from a to b, whereas the, point (x, f2 (x)) traces C2 as x decreases from b to a. Therefore,, , 冯 P dx � 冯, C, , P dx �, , C1, , �, , 冮, , b, , 冮, , b, , 冮, , b, , 冯, , P dx, , C2, , P(x, f1 (x)) dx �, , a, , �, �, , 冮, , a, , 冮, , b, , P(x, f2 (x)) dx, , b, , P(x, f1 (x)) dx �, , a, , C2, , y � f 2(x), , 1269, , The notation, , GEORGE GREEN, , y, , Green’s Theorem, , P(x, f2 (x)) dx, , a, , [P(x, f1 (x)) � P(x, f2(x))] dx, , (2), , a, , R, , Next, we find, C1, 0, , a, , b, , �P, , 冮冮 �y dA � 冮 冮, , y � f 1(x), b, , FIGURE 3, The simple region R viewed as a, y-simple region, , x, , a, , R, , �, , 冮, , f2(x), , f1(x), , �P, (x, y) dy dx, �y, , b, , [P(x, f2 (x)) � P(x, f1 (x))] dx, , (3), , a, , where the last equality is obtained with the aid of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus. Comparing Equation (3) with Equation (2), we see that, �P, , 冯 P dx � �冮冮 �y dA, C, , R, , (4)

Page 3 :

1270, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , By viewing R as an x-simple region (Figure 4),, , y, d, , R � {(x, y) 冟 c, , x � g2(y), , x � g1(y), R, , C1, , y, , d, t1(y), , x, , t2(y)}, , you can show in a similar manner that, , C2, , �Q, , 冯 Q dy � 冮冮 �x dA, , c, , C, , x, , 0, , FIGURE 4, The simple region R viewed as an, x-simple region, , (5), , R, , (See Exercise 48.) Adding Equation (4) and Equation (5), we obtain Equation (1), the, conclusion of Green’s Theorem for the case of a simple region., , EXAMPLE 1 Evaluate 养C x 2 dx � (xy � y 2) dy, where C is the boundary of the, , region R bounded by the graphs of y � x and y � x 2 and is oriented in a positive direction., y, , Solution The region R is shown in Figure 5. Observe that R is simple. Using Green’s, Theorem with P(x, y) � x 2 and Q(x, y) � xy � y 2, we have, , (1, 1), , 1, , 冯, , C, , y�x, , C, , y�x, , 2, , R, , x 2 dx � (xy � y 2) dy �, , R, , �, 0, , 冮, , 1, , 0, , x, , 1, , 冮冮, , c, , �Q, �P, �, d dA �, �x, �y, , y�x, 1, 1, c y2d, dx �, 2, 2, y�x2, , 1, , x, , 冮 冮 (y � 0) dy dx, 0, , 冮, , x2, , 1, , (x 2 � x 4) dx, , 0, , 1, , �, , FIGURE 5, The curve C is the boundary of, the region R., , 1 1 3 1 5, 1, a x � x b` �, 2 3, 5, 15, 0, , EXAMPLE 2 Evaluate 养C (y 2 � tan x) dx � (x 3 � 2xy � 1y) dy, where C is the, , circle x 2 � y 2 � 4 and is oriented in a positive direction., , Solution The simple region R bounded by C is the disk R � {(x, y) 冟 x 2 � y 2 4}, shown in Figure 6. Using Green’s Theorem with P(x, y) � y 2 � tan x and Q(x, y) �, x 3 � 2xy � 1y, we find, , y, x2 � y2 � 4, R, �2, , 0, , 2, , x, , C, , FIGURE 6, The region R is the disk bounded, by the circle x 2 � y 2 4., , �Q, � 3, �, (x � 2xy � 1y) � 3x 2 � 2y, �x, �x, , �P, � 2, �, (y � tan x) � 2y, �y, �y, , and, , and so, , 冯 (y, C, , 2, , � tan x) dx � (x 3 � 2xy � 1y) dy �, , �Q, , �P, , 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA � 冮冮 3x, R, , 冮 冮, , 2, , 2p, , 2, , 0, , �3, , 冮 冮, 冮, , (r cos u)2r dr du, , 0, , 0, , �3, , dA, , R, , 2p, , �3, , 2, , r 3 cos2 u dr du, , 0, , 0, , 2p, , r�2, 1, c r 4 cos2 ud, du, 4, r�0, , Use polar, coordinates.

Page 4 :

15.5, , � 12, , 冮, , 1271, , Green’s Theorem, , 2p, , cos2 u du, , 0, , �6, , 冮, , 2p, , (1 � cos 2u) du, , 0, , � 6cu �, , 2p, 1, sin 2ud � 12p, 2, 0, , The results obtained in Examples 1 and 2 can be verified by evaluating the given, line integrals directly without the benefit of Green’s Theorem, but this entails much, more work than evaluating the corresponding double integrals. In certain situations,, however, the opposite is true; that is, it is easier to evaluate a line integral than it is to, evaluate the corresponding double integral. This fact is exploited in the following formulas based on Green’s Theorem for finding the area of a plane region., , THEOREM 2 Finding Area Using Line Integrals, Let R be a plane region bounded by a piecewise-smooth simple closed curve C., Then the area of R is given by, A�, , 冯 x dy � � 冯 y dx � 2 冯 x dy � y dx, 1, , C, , C, , (6), , C, , PROOF Taking P(x, y) � 0 and Q(x, y) � x, Green’s Theorem gives, �Q, , �P, , 冯 x dy � 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA � 冮冮 1 dA � A, C, , R, , R, , Similarly, by taking P(x, y) � �y and Q(x, y) � 0, we have, �Q, , �P, , 冯 �y dx � 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA � 冮冮 1 dA � A, C, , R, , R, , Finally, with P(x, y) � �12 y and Q(x, y) � 12 x, we have, , 冯, , C, , �, , 1, 1, y dx � x dy �, 2, 2, , �Q, , �P, , 冯 P dx � Q dy � 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA � 冮冮 a 2 � 2 b dA � A, C, , 1, , R, , EXAMPLE 3 Find the area enclosed by the ellipse, , 1, , R, , x2, a2, , �, , y2, b2, , � 1., , Solution The ellipse C can be represented by the parametric equations x � a cos t, and y � b sin t, where 0 t 2p. Also observe that the ellipse is traced in the counterclockwise direction as t increases from 0 to 2p. Using Equation (6), we have, A�, �, , 1, 2, , 冯, , ab, 2, , x dy � y dx �, , C, , 冮, , 0, , 2p, , dt � pab, , 1, 2, , 冮, , 0, , 2p, , (a cos t)(b cos t) dt � (b sin t)(�a sin t) dt

Page 5 :

1272, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , Green’s Theorem for More General Regions, y, , So far, we have proved Green’s Theorem for the case in which R is a simple region,, but the theorem can be extended to the case in which the region R is a finite union of, simple regions. For example, the region R shown in Figure 7 is not simple, but it can, be written as R � R1 傼 R2, where R1 and R2 are both simple. The boundary of R1 is, C1 傼 C3, and the boundary of R2 is C2 傼 C4, where C3 and C4 are paths along the, crosscut traversed in the indicated directions., Applying Green’s Theorem to each of the regions R1 and R2 gives, , C1, , C3, , R1, , C4, R2, C2, x, , 0, , FIGURE 7, The region R is the union of two simple, regions R1 and R2., , 冯, , P dx � Q dy �, , 冯, , P dx � Q dy �, , C1 傼C3, , 冯, , x, , FIGURE 8, The region R is a union of three simple, regions R1, R2, and R3., , x2 � y2 � 9, , R, , �1, , 0, , �P, , R2, , 冯, , 冯, , P dx � Q dy �, , C2 傼C4, , P dx � Q dy �, , C1 傼C2, , �Q, , �P, , 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA, R, , which is Green’s Theorem for the region R � R1 傼 R2 with boundary C � C1 傼 C2., A similar argument enables us to establish Green’s Theorem for the general case, in which R is the union of any finite number of nonoverlapping, except perhaps for the, common boundaries, simple regions (see Figure 8)., , EXAMPLE 4 Evaluate 养C (ex � y 2) dx � (x 2 � 3xy) dy, where C is the positively oriented closed curve lying on the boundary of the semiannular region R bounded by the, upper semicircles x 2 � y 2 � 1 and x 2 � y 2 � 9 and the x-axis as shown in Figure 9., , y, , �3, , P dx � Q dy �, , C1 傼C3, , R2, , 0, , �Q, , 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA, , Adding these two equations and observing that the line integrals along C3 and C4 cancel each other, we obtain, , R3, , R1, , �P, , R1, , and, C2 傼C4, , y, , �Q, , 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA, , 1, , x, 3, x2 � y2 � 1, , FIGURE 9, The region R is divided into two, simple regions by the crosscut that, lies on the y-axis., , Solution The region R is not simple, but it can be divided into two simple regions by, means of the crosscut that is the intersection of R and the y-axis. Also notice that in, polar coordinates,, R � {(r, u) 冟 1 r 3, 0 u p}, Using Green’s Theorem with P(x, y) � ex � y 2 and Q(x, y) � x 2 � 3xy, we have, �Q, � 2, �, (x � 3xy) � 2x � 3y, �x, �x, , and, , �P, � x, �, (e � y 2) � 2y, �y, �y, , and so, , 冯 (e, , x, , � y 2) dx � (x 2 � 3xy) dy �, , C, , �Q, , R, , R, , 3, , p, , �, , 冮 冮 (2r cos u � r sin u)r dr du, 0, , �, , 冮, , 1, , p, , 0, , �, , �P, , 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA � 冮冮 (2x � y) dA, 3, 1, (2 cos u � sin u) c r 3 d du, 3, 1, , 26, 52, p, C2 sin u � cos uD 0 �, 3, 3, , Use polar, coordinates.

Page 6 :

15.5, y, R1, R, C2, R2, C1, x, , 0, , FIGURE 10, The annular region R can be divided, into two simple regions using two, crosscuts., , Green’s Theorem, , 1273, , Green’s Theorem can be extended to even more general regions. Recall that a region, R is simply-connected if for every simple closed curve C that lies in R, the region, bounded by C is also in R. Thus, as was noted earlier, a simply-connected region “has, no holes.” For example, a rectangle is simply-connected, but an annulus (a ring bounded, by two concentric circles) is not. Also, multiply-connected regions may have one or, more holes in them and also may have boundaries that consist of two or more simple, closed curves. For example, the annular region R shown in Figure 10 has a boundary, C consisting of two simple closed curves C1 and C2. Observe that C is traversed in the, positive direction provided that C1 is traversed in the counterclockwise direction and, C2 is traversed in the clockwise direction (so that the region R always lies to the left, as the curve is traced)., The region R can be divided into two simple regions, R1 and R2, by means of two, crosscuts, as shown in Figure 10. Applying Green’s Theorem to each of these subregions of R, we obtain, �Q, , �Q, , �P, , �Q, , �P, , �P, , 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA � 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA � 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA, R, , R1, , �, , R2, , 冮冮 P dx � Q dy � 冮冮 P dx � Q dy, �R1, , �R2, , where �R1 and �R2 denote the boundaries of R1 and R2, respectively. Since the line, integrals along the crosscuts are traversed in opposite directions, they cancel out, and, we have, �Q, , �P, , 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA � 冯, , P dx � Q dy �, , C1, , R, , 冯, , P dx � Q dy �, , C2, , 冯 P dx � Q dy, C, , which is Green’s Theorem for the region R. Observe that the second line integral above, is traversed in the clockwise direction., , EXAMPLE 5 Let C be a smooth, simple, closed curve that does not pass through the, origin. Show that, y, x, � 2, dx � 2, dy, 2, x, �, y, x, �, y2, C, , 冯, , is equal to zero if C does not enclose the origin but is equal to 2p if C encloses the, origin., y, , Solution Suppose that C does not enclose the origin. (See Figure 11.) Using Green’s, Theorem with P(x, y) � �y>(x 2 � y 2) and Q(x, y) � x>(x 2 � y 2) so that, �Q, (x 2 � y 2)(1) � x(2x), y2 � x 2, �, �, �x, (x 2 � y 2)2, (x 2 � y 2)2, , R, C, , 0, , FIGURE 11, C does not enclose the origin., , and, , x, , (x 2 � y 2)(�1) � (�y)(2y), y2 � x 2, �Q, �P, �, �, �, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, �y, �x, (x � y ), (x � y ), , we obtain, , 冯 �x, C, , y, 2, , �y, , 2, , dx �, , x, x �y, 2, , 2, , dy �, , �Q, , �P, , 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA � 冮冮 0 dA � 0, , Here, R denotes the region enclosed by C., , R, , R

Page 7 :

1274, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, y, , a, 0, , x, , R, C, , C, , Next, suppose that C encloses the origin. Since P and Q are not continuous in the, region enclosed by C, Green’s Theorem is not directly applicable. Let C¿ be a counterclockwise-oriented circle with center at the origin and radius a chosen small enough, so that C¿ lies inside C. (See Figure 12.) Then both P and Q have continuous partial, derivatives in the annular region bounded by C and C¿. Applying Green’s Theorem to, the multiply-connected region R with its positively oriented boundary C 傼 (�C¿), we, obtain, , 冯 P dx � Q dy � 冯, , FIGURE 12, C encloses the origin., , �C¿, , P dx � Q dy �, , C, , �Q, , �P, , 冮冮 c �x � �y d dA � 冮冮 0 dA � 0, R, , R, , or, upon reversing the direction of traversal of the second line integral,, , 冯 P dx � Q dy � 冯, C, , P dx � Q dy � 0, , C¿, , Therefore,, , 冯 P dx � Q dy � 冯, C, , P dx � Q dy, , C¿, , Up to this point, we have shown that the required line integral is equal to the line, integral taken over the circle C¿ in the counterclockwise direction. To evaluate this integral, we represent the circle by the parametric equations x � a cos t and y � a sin t,, where 0 t 2p. We obtain, , 冯, , C¿, , �, , y, x �y, 2, , 2, , dx �, , x, x �y, 2, , 2, , dy �, , 冮, , 2p, , 冮, , 2p, , �, , 0, , �, , (a sin t)(�a sin t), (a cos t) � (a sin t), 2, , 2, , dt �, , (a cos t)(a cos t), (a cos t)2 � (a sin t)2, , dt, , 1 dt � 2p, , 0, , Therefore,, , 冯 �x, C, , y, 2, , �y, , 2, , dx �, , x, x � y2, 2, , dy � 2p, , Vector Form of Green’s Theorem, The vector form of Green’s Theorem has two useful versions: one involving the curl, of a vector field and another involving the divergence of a vector field., Suppose that the curve C, the plane region R, and the functions P and Q satisfy the, hypothesis of Green’s Theorem. Let F � Pi � Qj be a vector field. Then, , 冯 F ⴢ T ds � 冯 P dx � Q dy, C, , C, , Recalling that P and Q are functions of x and y, we have, , curl F � §, , i, �, F�∞, �x, P, , j, �, �y, Q, , k, �Q, �, �P, ∞�a, �, bk, �z, �x, �y, 0, , Remember that P and Q are, functions of x and y.

Page 8 :

15.5, , Green’s Theorem, , 1275, , so, (curl F) ⴢ k � a, , �Q, �Q, �P, �P, �, bk ⴢ k �, �, �x, �y, �x, �y, , Therefore, Green’s Theorem can be written in the vector form, , 冯 F ⴢ T ds � 冮冮curl F ⴢ k dA, C, , (7), , R, , Equation (7) states that the line integral of the tangential component of F around, a closed curve C is equal to the double integral of the normal component to R of, curl F over the region R enclosed by C., Next, let the curve C be represented by the vector equation r(t) � x(t)i � y(t)j,, a t b. Then the outer unit normal vector to C is, n(t) �, , x¿(t), y¿(t), i�, j, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, , which you can verify by showing that n(t) ⴢ T(t) � 0, where, T(t) �, , y¿(t), x¿(t), i�, j, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, , is the unit tangent vector to C. (See Figure 13.) We have, , y, T(t) n(t), , 冯, , F ⴢ n ds �, , 冮, , b, , 冮, , b, , R, , �, , 冮, , b, , a, , r(t), , C, , 0, , (F ⴢ n)(t) 冟 r¿(t) 冟 dt, , a, , C, , �, , x, , c, , P(x(t), y(t))y¿(t), Q(x(t), y(t))x¿(t), �, d 冟 r¿(t) 冟 dt, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, 冟 r¿(t) 冟, , P(x(t), y(t))y¿(t) dt �, , a, , FIGURE 13, n(t) is the outer normal vector to C., , �, , 冮, , b, , Q(x(t), y(t))x¿(t) dt, , a, , 冯 P dy � Q dx, C, , But by Green’s Theorem,, �, , �, , 冯 P dy � Q dx � 冮冮 c �x (P) � �y (�Q)d dA, C, , R, , �, , �P, , �Q, , 冮冮 a �x � �y b dA, R, , Observing that the integrand of the last integral is just the divergence of F, we obtain, the second vector form of Green’s Theorem:, , 冯 F ⴢ n ds � 冮冮 div F dA, C, , (8), , R, , Equation (8) states that the line integral of the normal component of F around a closed, curve C is equal to the double integral of the divergence of F over R.

Page 9 :

1276, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , 15.5, , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, , 1. State Green’s Theorem., , 15.5, , 2. Write three line integrals that give the area of a region, bounded by a piecewise smooth curve C., , EXERCISES, , In Exercises 1–4, evaluate the line integral (a) directly and, (b) by using Green’s Theorem, where C is positively oriented., 1., , 冯, , 11., , x, , 2xy dx � 3xy 2 dy, where C is the square with vertices, , C, , 12., , (0, 0), (1 , 0), (1, 1), and (0, 1), , 冯, , (x 2 � y) dx � 21 � y 2 dy, where C is the astroid, , C, 2>3, , � y 2>3 � a 2>3, , 冯 6xy dx � (3x, , 2, , � ln(1 � y)) dy, where C is the cardioid, , C, , 2., , 冯x, , 2, , r � 1 � cos u, , dx � xy dy, where C is the triangle with vertices, , C, , 13., , (0, 0), (1, 0), and (0, 1), 3., , 冯y, , 2, , (x � ex sin y) dx � (x � ex cos y) dy, where C is the, y2, x2, ellipse, �, �1, 9, 4, C, , dx � (x 2 � 2xy) dy, where C is the boundary of the, , C, , region bounded by the graphs of y � x and y � x 3 lying in, the first quadrant, 4., , 冯, , 冯 2x dx � 3y dy, where C is the circle x, , 2, , � y2 � a2, , C, , 14., , 冯, , y, , dx � (x � tan�1 x) dy, where C is the right-hand, 1 � x2, loop of the lemniscate r 2 � cos 2u, C, , 15., , 冯, , (�y dx � x dy), where C is the boundary of the annular, , C, , region formed by circles x 2 � y 2 � 1 and x 2 � y 2 � 4, , In Exercises 5–16, use Green’s Theorem to evaluate the line, integral along the positively oriented closed curve C., 5., , 冯x, , 16., 3, , dx � xy dy, where C is the triangle with vertices, , (0, 0), (1 , 1), and (0, 1), , 冯, , (x 2 � y 2) dx � 2xy dy, where C is the square with, , C, , vertices ( 1,, 7., , 冯, , 1), , (x 2y � x 3) dx � 2xy dy, where C is the boundary of the, , C, , region bounded by the graphs of y � x and y � x 2, 8., , 冯, , 2, , (�y 3 � cos x) dx � e y dy, where C is the boundary of, , C, , 9., , 3, , 17. Use Green’s Theorem to find the work done by the force, F(x, y) � (x 2 � y 2)i � 2xyj in moving a particle in the positive direction once around the triangle with vertices (0, 0),, (1, 0), and (0, 1)., 18. Use Green’s Theorem to find the work done by the force, F(x, y) � 3yi � 2xj in moving a particle once around the, y2, x2, ellipse, �, � 1 in the clockwise direction., 4, 9, , the region bounded by the parabolas y � x 2 and x � y 2, , In Exercises 19–22, use one of the formulas on page 1271 to find, the area of the indicated region., , 冯, , 19. The region enclosed by the astroid x 2>3 � y 2>3 � a 2>3, , (y 2 � cos x) dx � (x � tan�1 y) dy, where C is the, , C, , boundary of the region bounded by the graphs of, y � 4 � x 2 and y � 0, 10., , � x) dy, where C is the boundary of, y2, x2, �, � 1 and the, the region lying between the ellipse, 4, 9, circle x 2 � y 2 � 1, 2, , C, , C, , 6., , 冯 3x y dx � (x, , 冯, , x 2y dx � y 3 dy, where C consists of the line segment, , C, , from (�1, 0) to (1, 0) and the upper half of the circle, x 2 � y2 � 1, , 20. The region bounded by an arc of the cycloid, x � a(t � sin t), y � a(1 � cos t), and the x-axis, 21. The region enclosed by the curve x � a sin t and, y � b sin 2t, 22. The region enclosed by the curve x � cos t and y � 4 sin3 t,, where 0 t 2p, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login.

Page 10 :

15.5, 23. a. Plot the curve C defined by x � t(1 � t 2) and, y � t 2 (1 � t 3) , where 0 t 1., b. Find the area of the region enclosed by the curve C., , 2, , Hint: Use Green’s Theorem, noting that C1 傼 C2, where C2 is the, straight path from (�3, 0) to (3, 0), is a closed path., y, , 25. Swallowtail Catastrophe, a. Plot the swallowtail catastrophe defined by x � 2t(1 � t 2), and y � 12 t 2(3t 2 � 2), where �1 t 1., b. Find the area of the region enclosed by the swallowtail, catastrophe., , 冮, , F ⴢ dr � 3p,, , C2, , where F(x, y) � P(x, y)i � Q(x, y)j, and that, �Q, �P, �, b � 6 for all (x, y) in the region R bounded by, a, �x, �y, the circles C1 and C2, and oriented in a counterclockwise, direction. Use Green’s Theorem to find, , 冮, , 2, , C1, , B(�3, 0), , A(3, 0), 0, , �3, , C2, , Hint: See the hint in Exercise 28., y, 3, , F ⴢ dr., 2, , y, 1, , C2, , C1, , D, , 0, , C1, 1, , x, , 2, , R, , 27. Refer to the figure below. Suppose that, , 冯, , 冯, , B, , F ⴢ dr � 2p and, , A�, , F ⴢ dr � 3p, where F(x, y) � P(x, y)i � Q(x, y)j,, , C3, , �Q, �P, �, b � 6 for all (x, y) in the region R, �x, �y, lying inside the curve C1 and outside the curves C2 and C3., Use Green’s Theorem to find, , 冯, , 31., , C1, R, , 1, , C3, , �4 �3 �2 �1, �1, , 1, , C2, , 3, , 4, , x, , 5, , 1, [(x 1y2 � x 2y1) � (x 2y3 � x 3y2) � p, 2, � (x n�1yn � x nyn�1) � (x ny1 � x 1yn)], , 32., , y, , C1, , 2, , 2, , In Exercises 31 and 32, use the result of Exercise 30 to find the, area of the shaded region., , F ⴢ dr., , y, 3, , 1, , A, , 30. a. Let C be the line segment joining the points (x 1, y1) and, (x 2, y2). Show that 兰C �y dx � x dy � x 1y2 � x 2y1., b. Use the result of part (a) to show that the area of a polygon with vertices (x 1, y1), (x 2, y2), p , (x n, yn) (appearing, in the counterclockwise order) is, , C2, , and that a, , C, , E, F, , 0, , x, , 3, , 29. Evaluate 兰C1(x 2 � 2y) dx � (3x � sinh y) dy, where C1 is, the path ABCDEF shown in the figure., , C1, , �2, , 1277, , 28. Evaluate 兰C (x 2 � 2y) dx � 1 4x � e y 2 dy, where C1 is the, 1, semi-elliptical path from A to B shown in the figure., , 24. a. Plot the deltoid defined by x � 14 (2 cos t � cos 2t) and, y � 14 (2 sin t � sin 2t) , where 0 t 2p., b. Find the area of the region enclosed by the deltoid., , 26. Refer to the following figure. Suppose that, , Green’s Theorem, , �5, , 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0, �2, , 1 2 3 4 5, , x, , y, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, _4, , 0, , 1 2 3 4 5, , x, , _4, , �2, �3, , 2, , 3, , 4 x, , In Exercises 33 and 34, use the result of Exercise 30 to find the, area of the polygon., 33. Pentagon with vertices (0, 0) , (2, 0) , (3, 1), (1, 3) , and, (�1, 1)., 34. Hexagon with vertices (0, 0) , (3, 0) , (4, 1) , (2, 4) , (0, 3), and, (�2, 1).

Page 11 :

1278, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , 35. Let R be a plane region of area A bounded by a piecewisesmooth simple closed curve C. Use Green’s Theorem to, show that the centroid of R is (x, y), where, x�, , 冯x, , 1, 2A, , 2, , y��, , dy, , C, , 冯y, , 1, 2A, , 2, , 36. The triangle with vertices (0, 0), (1, 0), and (1, 1)., 37. The region bounded by the graphs of y � 0 and y � 9 � x 2., 38. A plane lamina with constant density r has the shape of, a region bounded by a piecewise-smooth simple closed, curve C. Show that its moments of inertia about the axes are, , 冯y, , 3, , r, Iy �, 3, , dx, , C, , 冯x, , 3, , dy, , C, , 39. Use the result of Exercise 38 to find the moment of inertia, of a circular lamina of radius a and constant density r about, a diameter., 40. Show that if f and t have continuous derivatives, then, , 冯 f(x) dx � t(y) dy � 0, , 冯, , for every piecewise-smooth simple closed curve C., 41. Let C be a piecewise-smooth simple closed curve that, encloses a region R of area A. Show that, (ay � b) dx � (cx � d) dy � (c � a)A, , (cos x � x 3y) dx � (x 4 � ey) dy � 0, , C, , where C is the boundary of the square with vertices, (�1, �1), (1, �1), (1, 1), and (�1, 1)., b. Note that, �, � 4, (x � e y) �, (cos x � x 3y), �x, �y, Does this contradict Theorem 4 of Section 15.4?, Explain., c. Evaluate the line integral of part (a), taking C to be the, boundary of the square with vertices (0, 0), (1, 0), (1, 1),, and (0, 1)., 46. Can Green’s Theorem be applied to evaluate, , 冯, , x, , C, , C, , 冯, , 冯, , 45. a. Use Green’s Theorem to show that, , dx, , C, , In Exercises 36 and 37, use the result of Exercise 35 to find the, centroid of the region., , r, Ix � �, 3, , �Q, �P, �, P dx � Q dy � 0., in R but, �y, �x, C, b. Does this contradict Green’s Theorem? Explain., a. Show that, , 2(x � 2) � y, 2, , 2, , dx �, , y, 2(x � 2)2 � y 2, , dy, , where C is the circle of radius 1 centered at the origin?, Explain., 47. Show that if P( y) and Q(x) have continuous derivatives,, then, , 冯 P(y) dx � Q(x) dy � 2CQ(t) � P(t) D, C, , t�1, t��1, , C, , 42. Let C be a piecewise-smooth simple closed curve that does, not pass through the origin. Evaluate, , 冯, , x, , C, , x �y, 2, , 2, , dx �, , y, x � y2, 2, , 48. Refer to the proof of Green’s Theorem. Show that by viewing R as an x-simple region, we have, , dy, , (a) where C does not enclose the origin and (b) where C, encloses the origin., 43. Let P(x, y) � �, a. Show that, , 冯, , y, x �y, 2, , 2, , and Q(x, y) �, , x, x �y, 2, , 2, , (P dx � Q dy) � 0, where C is the circle, , of radius 1 centered at the origin., �Q, �P, �, b. Verify that, ., �y, �x, c. Do parts (a) and (b) contradict each other? Explain., 44. Let R be the region bounded by the circles of radius 1 and 3, centered at the origin, and let C be the circle of radius 2, centered at the origin described by r(t) � 2 cos ti � 2 sin tj,, where 0 t 2p. Let, y, x 2 � y2, , and, , Q(x, y) �, , �Q, , 冯 Q dy � 冮冮 �x dA, C, , R, , ., , C, , P(x, y) � �, , where C is the rectangular path that is traced in a counterclockwise direction with vertices (�1, �1), (1, �1), (1, 1),, and (�1, 1)., , x, x 2 � y2, , In Exercises 49–51, determine whether the statement is true or, false. If it is true, explain why. If it is false, explain why or give, an example that shows it is false., 49. If a and b are constants, then 养C a dx � b dy � 0, where C, is a simple closed curve., 50. If C is a piecewise-smooth simple closed curve that bounds, a region R in the plane, then 养C xy 2 dx � (x 2y � x) dy is, equal to the area of R., 51. The work done by the force field F(x, y) � �12 yi � 12 xj on a, particle that moves once around a piecewise-smooth simple, closed curve in a counterclockwise direction is numerically, equal to the area of the region bounded by the curve.

Page 12 :

15.6, , 15.6, , Parametric Surfaces, , 1279, , Parametric Surfaces, Why We Use Parametric Surfaces, z, 4π, , 1, , 1, (x, y), , y, , x, , FIGURE 1, The helicoid shown here, is not the graph of a, function z � f(x, y)., , In Chapter 13 we studied surfaces that are graphs of functions of two variables. However, not every surface is the graph of a function z � f(x, y). Consider, for example,, the helicoid shown in Figure 1. Observe that the point (x, y) in the xy-plane is associated with more than one point on the helicoid, so this surface cannot be the graph of, a function z � f(x, y)., Just as we found it useful to describe a curve in the plane (and in space) as the, image of a line under a vector-valued function r rather than as the graph of a function,, we will now see that a similar situation exists for surfaces. Instead of a single parameter, however, we will use two parameters and view a surface in space as the image of, a plane region. More specifically, we have the following., , DEFINITION Parametric Surface, Let, r(u, √) � x(u, √)i � y(u, √)j � z(u, √)k, be a vector-valued function defined for all points (u, √) in a region D in the, u√-plane. The set of all points (x, y, z) in R3 satisfying the parametric equations, x � x(u, √),, , y � y(u, √),, , z � z(u, √), , as (u, √) ranges over D is called a parametric surface S represented by r. The, region D is called the parameter domain., , Thus, as (u, √) ranges over D, the tip of the vector r(u, √) traces out the surface S, (see Figure 2). Put another way, we can think of r as mapping each point (u, √) in D, onto a point (x(u, √), y(u, √), z(u, √)) on S in such a way that the plane region D is bent,, twisted, stretched, and/or shrunk to yield the surface S., z, , y, , S, , r, D, , r(u, √), , (u, √), , FIGURE 2, The function r maps D, onto the surface S., , 0, , 0, y, , x, , x, , EXAMPLE 1 Identify and sketch the surface represented by, r(u, √) � 2 cos ui � 2 sin uj � √k, with parameter domain D � {(u, √) 冟 0, Solution, , (x, y, z), , u, , 2p, 0, , √, , 3}., , The parametric equations for the surface are, x � 2 cos u,, , y � 2 sin u,, , z�√

Page 13 :

1280, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , Eliminating the parameters u and √ in the first two equations, we obtain, x 2 � y 2 � 4 cos2 u � 4 sin2 u � 4, Observe that the variable z is missing in this equation, so it represents a cylinder with, the z-axis as its axis. (See Section 11.6.) Furthermore, the trace in the xy-plane is a circle of radius 2, and we conclude that the cylinder is a circular cylinder. Finally, because, 0 √ 3, the third equation z � √ tells us that 0 z 3. Thus, the required surface, is the truncated cylinder shown in Figure 3., z, , √, , (x, y, z), , 3, , r, r(u, √), , 3, D, , FIGURE 3, The function r “bends” the rectangular, region D into a cylinder., , 2, 0, , u, , 2π, , 2, , y, , x, , There is another way of visualizing the way r maps the domain D onto a surface, S. If we fix u by setting u � u 0, where u 0 is a constant, and allow √ to vary so that the, points (u 0, √) lie in D, then we obtain a vertical line segment L 1 lying in D. When, restricted to L 1, the function r becomes a function involving one parameter √ whose, domain is the parameter interval L 1. Therefore, r(u 0, √) maps L 1 onto a curve C1 lying, on S (see Figure 4)., √, , z, C2, , L1, D, √0, , C1, , r, , u � u0, , √ � √0 (u0, √0), 0, , L2, , FIGURE 4, r maps L 1 onto C1 and L 2 onto C2., , 0, , u0, , u, , r(u0, √), , y, , x, , Similarly, by holding √ fixed, say, √ � √0, where √0 is a constant, the tip of the resulting vector r(u, √0) traces the curve C2 as u is allowed to assume values in the parameter interval L 2. The curves C1 and C2 are called grid curves., By way of illustration, if we set u � u 0 in Example 1, then both x � 2 cos u 0 and, y � 2 sin u 0 are constant. So the vertical line u � u 0 is mapped onto the vertical line, segment (2 cos u 0, 2 sin u 0, √) , 0 √ 3. Similarly, you can verify that a horizontal, line segment √ � √0 in D is mapped onto a circle on the cylinder at a height of √0 units, from the xy-plane., , EXAMPLE 2 Use a computer algebra system (CAS) to generate the surface represented by, r(u, √) � sin u cos √i � sin u sin √j � cos uk

Page 14 :

15.6, , Parametric Surfaces, , 1281, , with parameter domain D � {(u, √) 冟 0 u p, 0 √ 2p}. Identify the curves on, the surface that correspond to the curves with u held constant and those with √ held, constant., Solution The required surface is the unit sphere centered at the origin. (See Figure 5a.), You can verify that this is the case by eliminating u and √ in the parametric equations, x � sin u cos √,, , y � sin u sin √,, , z � cos u, , to obtain the rectangular equation x � y � z � 1 for the sphere. Fixing u � u 0,, where u 0 is a constant, leads to the equations, 2, , x � sin u 0 cos √,, , 2, , 2, , y � sin u 0 sin √,, , z � cos u 0, , We have, x 2 � y 2 � sin2 u 0 cos2 √ � sin2 u 0 sin2 √, � sin2 u 0 (cos2 √ � sin2 √) � sin2 u 0, The system of equations, x 2 � y 2 � sin2 u 0, z � cos u 0, , v, , for a fixed u 0 lying in [0, p] or, equivalently, the vector-valued function, r(u 0, √) � sin u 0 cos √i � sin u 0 sin √j � cos u 0k, represents a circle of radius sin u 0 on the sphere that is parallel to the xy-plane. Thus,, if we think of the sphere as a globe then the horizontal line segments in the domain of, r are mapped onto the latitudinal lines, or parallels. (See Figure 5b.) Similarly, we can, show that the vertical line segments in the domain of r with √ � √0, where √0 is a constant, are mapped by, r(u, √0) � sin u cos √0i � sin u sin √0 j � cos uk, onto the meridians of longitude—great circles on the surface of the globe passing, through the poles., , 1.0, , 0.5, , z, , �1.0, �0.5, 0.0, , 1.0, Parallels (u � u0), 0.5, 0.0, y, �0.5, �1.0, �1.0, , FIGURE 5, , (a), , x, , �0.5, , 0.0, , 0.5, , 1.0, , Meridians (√ � √0), , (b), , Finding Parametric Representations of Surfaces, We now turn our attention to finding vector-valued function representations of surfaces., We begin by showing that if a surface is the graph of a function f(x, y), then it has a, simple parametric representation.

Page 15 :

1282, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , EXAMPLE 3, a. Find a parametric representation for the graph of a function f(x, y)., b. Use the result of part (a) to find a parametric representation for the elliptic paraboloid z � 4x 2 � y 2., z, z � f (x, y), , (x, y, f(x, y)), , x � x(u, √) � u,, , S, r(u, √), , f (u, √)k, , 0, y(√), , ui � √j, , Solution, a. Suppose that S is the graph of z � f(x, y) defined on a domain D in the xy-plane., (See Figure 6.) We simply pick x and y to be the parameters; in other words, we, write the desired parametric equations as, , D, , x(u), , z � z(u, √) � f(u, √), , and take the domain of f to be the parameter domain. Equivalently, we obtain the, vector-valued representation by writing, r(u, √) � ui � √j � f(u, √)k, b. The surface is the graph of the function f(x, y) � 4x 2 � y 2. So we can let x and y, be the parameters. Thus, the required parametric equations are, , (x, y)�(u, √), , FIGURE 6, The vector r(u, √) � ui � √j � f(u, √)k, by the rule for vector addition., , y � y(u, √) � √,, , x � u,, , z � 4u 2 � √2, , y � √,, , and the corresponding vector-valued function is, r(u, √) � ui � √j � (4u 2 � √2)k, The parameter domain is D � {(u, √) 冟 �⬁ � u � ⬁, �⬁ � √ � ⬁}., , EXAMPLE 4 Find a parametric representation for the cone x � 2y 2 � z 2., Solution The surface is the graph of the function f(y, z) � 2y 2 � z 2. So we can let, y and z be the parameters. Thus, the required parametric equations are, x � 2u 2 � √2,, , y � u,, , z�√, , and the corresponding vector-valued function is, r(u, √) � 2u 2 � √2 i � uj � √k, The parameter domain is D � {(u, √) 冟 �⬁ � u � ⬁, �⬁ � √ � ⬁}., , EXAMPLE 5, a. Find a parametric representation of the plane that passes through the point P0 with, position vector r0 and contains two nonparallel vectors a and b., b. Using the result of part (a), find a parametric representation of the plane passing, through the point P0 (3, �1, 1) and containing the vectors a � �2i � 5j � k and, b � �3i � 2j � 3k. (This is the plane in Example 6 in Section 11.5.), , z, , P0, , b, a, r0, , √b, , P0 P, P, , ua, r, , O, y, x, , FIGURE 7, r � r0 � P0P៝ � r0 � ua � √b, , Solution, a. Let P be a point lying on the plane, and let r � OP៝. Since P0P៝ lies in the plane, determined by a and b, there exist real numbers u and √ such that P0P៝ � ua � √b., (See Figure 7.) Furthermore, we see that r � r0 � P0P៝ � r0 � ua � √b. Finally,, since any point on the plane is located at the tip of r for an appropriate choice of, u and √, we see that the required representation is, r(u, √) � r0 � ua � √b

Page 16 :

15.6, , Parametric Surfaces, , 1283, , The parameter domain is D � {(u, √) 冟 �⬁ � u � ⬁, �⬁ � √ � ⬁}., b. The required representation is, r(u, √) � (3i � j � k) � u(�2i � 5j � k) � √(�3i � 2j � 3k), � (�2u � 3√ � 3)i � (5u � 2√ � 1)j � (u � 3√ � 1)k, with domain D � {(u, √) 冟 �⬁ � u � ⬁, �⬁ � √ � ⬁}., Note The representation in Example 5b is by no means unique. For example, an, equation of the plane in question is 13x � 3y � 11z � 47. (See Example 6 in Section, 11.5.) Solving this equation for z in terms of x and y, we obtain z � f(x, y) �, 1, 11 (47 � 13x � 3y) . Thus, the plane is the graph of the function f, and this observation, leads us to the representation, r(u, √) � ui � √j � a, , 47 � 13u � 3√, bk, 11, , The next two examples involve surfaces that are not graphs of functions., , EXAMPLE 6 Find a parametric representation for the cone x 2 � y 2 � z 2., Solution The cone has a simple representation r 2 � z 2 in cylindrical coordinates. This, suggests that we choose r and u as parameters. Writing u for r and √ for u, we have, x � u cos √,, , y � u sin √,, , z�u, , as the required parametric equations. In vector form we have, r(u, √) � u cos √i � u sin √j � uk, , EXAMPLE 7 Find a parametric representation for the helicoid shown in Figure 1., Solution, , Recall that the parametric equations for a helix are, x � a cos u,, , y � a sin u,, , z�u, , where u and z are in cylindrical coordinates. This suggests that we let u denote r and, √ denote u. Then the parametric equations for the helicoid are, x � u cos √,, , z, , y � u sin √,, , z�√, , with parameter domain D � {(u, √) 冟 �1 u 1, 0 √ 4p}. In vector form we, have, r(u, √) � u cos √i � u sin √j � √k, a, f(u), √, b, , y � f(x), , x, , FIGURE 8, S is obtained by revolving the graph, of f between x � a and x � b about, the x-axis., , y, , We now turn our attention to finding the parametric representation for surfaces of, revolution. Suppose that a surface S is obtained by revolving the graph of the function, y � f(x) for a x b about the x-axis, where f(x) � 0. (See Figure 8.) Letting u, denote x and √ denote the angle shown in the figure, we see that if (x, y, z) is any point, on S, then, x � u,, y � f(u) cos √,, z � f(u) sin √, (1), or, equivalently,, r(u, √) � ui � f(u) cos √j � f(u) sin √k, The parameter domain is D � {(u, √) 冟 a, , u, , b, 0, , √, , 2p}.

Page 17 :

1284, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , EXAMPLE 8 Gabriel’s Horn Find a parametric representation for the surface obtained by revolving the graph of f(x) � 1>x, where 1 x � ⬁ , about the x-axis., , z, 1, , Solution, 1, , 1, , Using Equation (1), we obtain the parametric equations, x � u,, , y, , y�, , 1, cos √,, u, , z�, , with parametric domain D � {(u, √) 冟 1 u � ⬁, 0 √, is a portion of Gabriel’s Horn as shown in Figure 9., , 1, sin √, u, 2p}. The resulting surface, , x, , FIGURE 9, Gabriel’s Horn, , Tangent Planes to Parametric Surfaces, Suppose that S is a parametric surface represented by the vector function, r(u, √) � x(u, √)i � y(u, √)j � z(u, √)k, and P0 is a point on the surface S represented by the vector r(u 0, √0), where (u 0, √0) is, a point in the parameter domain D of r. If we fix u by putting u � u 0 and allow √ to, vary, then the tip of r(u 0, √) traces the curve C1 lying on S. (See Figure 10.) The tangent vector to C1 at P0 is given by, r√ (u 0, √0) �, , �y, �x, �z, (u 0, √0)i �, (u 0, √0)j �, (u 0, √0)k, �√, �√, �√, , Similarly, by holding √ fast, √ � √0, and allowing u to vary, the tip of r(u, √0) traces, the curve C2 lying on S, with tangent vector at P0 given by, ru(u 0, √0) �, , �y, �x, �z, (u 0, √0)i �, (u 0, √0)j �, (u 0, √0)k, �u, �u, �u, , If ru (u, √) r√(u, √) � 0 for each (u, √) in the parameter domain of r, then the surface S is said to be smooth. For a smooth surface the tangent plane to S at P0 is the, plane that contains the tangent vectors ru (u 0, √0) and r√ (u 0, √0) and thus has a normal, vector given by, n � ru (u 0, √0), , r√(u 0, √0), , √, , n � ru, , z, , r√, , r√(u0, √0 ), D, √0, , √ � √0, , ru(u0, √0 ), , r, , u � u0, , C2, , (u0, √0 ), 0, , FIGURE 10, , 0, , u0, , u, , C1, , P0, , r(u0, √0 ), y, , x, , EXAMPLE 9 Find an equation of the tangent plane to the helicoid, r(u, √) � u cos √i � u sin √j � √k, of Example 7 at the point where u � 12 and √ � p4 .

Page 18 :

15.6, , Solution, , Parametric Surfaces, , 1285, , We start by finding the partial derivatives of r. Thus,, ru (u, √) � cos √i � sin √j, r√(u, √) � �u sin √i � u cos √j � k, , So, 1 p, 12, 12, ru a , b �, i�, j, 2 4, 2, 2, 1 p, 1 12, 1 12, 12, 12, r√ a , b � � ⴢ, i� ⴢ, j�k��, i�, j�k, 2 4, 2, 2, 2, 2, 4, 4, A normal vector to the tangent plane is, 1 p, n � ru a , b, 2 4, , i, 1 p, 12, r√ a , b � 5, 2 4, 2, 12, �, 4, , j, 12, 2, 12, 4, , k, 05 �, , 12, 1, 12, i�, j� k, 2, 2, 2, , 1, , Since any normal vector will do, let’s take n � 12i � 12j � k., Next note that the point 1 12 , p4 2 in the parameter domain is mapped onto the point, with coordinates, x0 �, , 1, p, 1 12, 12, cos � ⴢ, �, ,, 2, 4, 2, 2, 4, , y0 �, , 1, p, 12, sin �, ,, 2, 4, 4, , Therefore, an equation of the required tangent plane at, 12 ax �, , 1 124, 124, p4 2 is, , z0 �, , p, 4, , 12, 12, p, b � 12 ay �, b � 1az � b � 0, 4, 4, 4, 12x � 12y � z �, , p, �0, 4, , or, 412x � 412y � 4z � p � 0, , Area of a Parametric Surface, In Section 14.5, we learned how to find the area of a surface that is the graph of a function z � f(x, y). We now take on the task of finding the areas of parametric surfaces,, which are more general than the surfaces (graphs) defined by functions., For simplicity, let’s assume that the parametric surface S defined by, r(u, √) � x(u, √)i � y(u, √)j � z(u, √)k, has parameter domain R that is a rectangle. (See Figure 11.) Let P be a regular partition of R into n � mn subrectangles R11, R12, p , Rmn. The subrectangle Rij is mapped, by r onto the patch Sij with area denoted by ⌬Sij. Since the subrectangles Rij are nonoverlapping, except for their common boundaries, so are the patches Sij, and so the area of, S is given by, m, , n, , S � a a ⌬Sij, i�1 j�1

Page 19 :

1286, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , y, , S, , z, , Pij, , Sij, , R, Rij, r, , Δ√, , 0, , FIGURE 11, The subrectangle Rij is, mapped onto the patch Sij., , (ui, √j), , Δu, , y, , x, , 0, , x, , Next, let’s find an approximation of ⌬Sij. Let (u i, √j) be the corner of Rij closest to, the origin with image the point Pij represented by r(u i, √j) as shown in Figure 12. For, the sake of clarity, both Rij and Sij are shown enlarged. The sides of Sij with corner represented by r(u i, √j) are approximated by a and b, where a � r(u i � ⌬u, √j) � r(u i, √j), and b � r(u i, √j � ⌬√) � r(u i, √j). So ⌬Sij may be approximated by the area of the parallelogram with a and b as adjacent sides, that is,, ⌬Sij ⬇ 冟 a, , b冟, z, , (ui, √j � Δ√), , Sij, , (ui � Δu, √j � Δ√), Pij, Rij, , r(ui, √j), , (ui, √j), , b, a, , r(ui � Δu, √j), , (ui � Δu, √j), y, , FIGURE 12, , x, , But we can write, a�c, , r(u i � ⌬u, √j) � r(u i, √j), ⌬u, , d ⌬u, , If ⌬u is small, as we assume, then the term inside the brackets is approximately equal, to ru(u i, √j). So, a ⬇ ⌬u ru(u i, √j), Similarly, we see that, b ⬇ ⌬√ r√(u i, √j), Therefore,, ⌬Sij ⬇ 冟 [⌬u ru (u i, √j)] [⌬√ r√(u i, √j)] 冟, � 冟 ru(u i, √j), , r√(u i, √j) 冟 ⌬u ⌬√, , and the area of S may be approximated by, m, , n, , a a 冟 ru(u i, √j), i�1 j�1, , r√ (u i, √j) 冟 ⌬u ⌬√

Page 20 :

15.6, , Parametric Surfaces, , 1287, , Intuitively, the approximation gets better and better as m and n get larger and larger., But the double sum is the Riemann sum of 冟 ru r√ 冟, and we are led to define the area, of S as, m, , lim, , n, , a a 冟 ru(u i, √j), , r√ (u i, √j) 冟 ⌬u ⌬√, , m, n→⬁ i�1 j�1, , Alternatively, we have the following definition., , DEFINITION Surface Area (Parametric Form), Let S be a smooth surface represented by the equation, r(u, √) � x(u, √)i � y(u, √)j � z(u, √)k, with parameter domain D. If S is covered just once as (u, √) varies throughout, D, then the surface area of S is, A(S) �, , 冮冮 冟 r, , r√ 冟 dA, , u, , (2), , D, , EXAMPLE 10 Find the surface area of a sphere of radius a., Solution, tion, , The sphere centered at the origin with radius a is represented by the equar(u, √) � a sin u cos √i � a sin u sin √j � a cos uk, , with parameter domain D � {(u, √) 冟 0, , u, , p, 0, , √, , 2p}. We find, , ru(u, √) � a cos u cos √i � a cos u sin √j � a sin uk, r√(u, √) � �a sin u sin √i � a sin u cos √j, and so, i, j, k, r√ � † a cos u cos √ a cos u sin √ �a sin u †, �a sin u sin √ a sin u cos √, 0, , ru, , � a 2 sin2 u cos √i � a 2 sin2 u sin √j � a 2 sin u cos uk, Therefore, 冟 ru, , r√ 冟 � 2a 4 sin4 u cos2 √ � a 4 sin4 u sin2 √ � a 4 sin2 u cos2 u, � 2a 4 sin4 u � a 4 sin2 u cos2 u � 2a 4 sin2 u, � a 2 sin u, , since sin u � 0 for 0, A�, , 冮冮, , 冟 ru, , D, , �, , 冮, , 0, , 2p, , u, , p. Using Equation (2), the area of the sphere is, r√ 冟 dA �, , 2p, , 冮 冮, 0, , p, , 0, , C�a 2 cos uD u�0 d√ �, u�p, , a 2 sin u du d√, , 冮, , 0, , 2p, , 2a 2 d√ � 2a 2(2p) � 4pa 2

Page 21 :

1288, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , EXAMPLE 11 Find the area of one complete turn of the helicoid of width one represented by the equation r(u, √) � u cos √i � u sin √j � √k with parameter domain, D � {(u, √) 冟 0 u 1, 0 √ 2p}. (Refer to Figure 1.), Solution, , We first find, ru � cos √i � sin √j, r√ � �u sin √i � u cos √j � k, , and so, i, r√ � † cos √, �u sin √, , ru, , j, k, sin √ 0 †, u cos √ 1, , � sin √i � cos √j � (u cos2 √ � u sin2 √)k, � sin √i � cos √j � uk, Therefore,, 冟 ru, , r√ 冟 � 2sin2 √ � cos2 √ � u 2 � 21 � u 2, , So, the required area is, A�, , 冮冮, , 冟 ru, , D, , �, , 冮, , 2p, , 冮, , 2p, , 0, , �, , 0, , r√ 冟 dA �, , 2p, , 1, , 冮 冮 21 � u, 0, , 2, , du d√, , 0, , u�1, u, 1, c 21 � u 2 � ln(u � 21 � u 2)d, d√, 2, 2, u�0, , 1, 1, c 12 � ln(1 � 12)d d√, 2, 2, , Use Formula 37 from the, Table of Integrals., , � p[ 12 � ln(1 � 12)] ⬇ 7.212, , 15.6, 1. a., b., 2. a., b., , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, , Define a parametric surface., What are the grid curves of a parametric surface?, What is a smooth surface?, Explain how you would find an equation of the tangent, plane to a smooth surface with representation r(u, √) at, the point represented by r(u 0, √0)., , 3. Write a double integral giving the area of a surface S, defined by a vector function r(u, √), where (u, √) lies in the, parameter domain D of r.

Page 22 :

15.6, , 15.6, , 1289, , Parametric Surfaces, , EXERCISES, u, 14. r(u, √) � c2 cos u � √ cosa b d i, 2, u, u, � c2 sin u � √ cosa b d j � √ sina bk;, 2, 2, 0 u 2p, �12, , In Exercises 1–4, match the equation with one of the graphs, labeled (a)–(d). Give a reason for your choice., 1. r(u, √) � 2 cos ui � 2 sin uj � √k, 2. r(u, √) � u cos √i � u sin √j � uk, 3. r(u, √) � u cos √i � u sin √j � u 2k, , 1, 2, , √, , Note: This is a representation for the Möbius strip., , 4. r(u, √) � u cos √i � u sin √j � √k, In Exercises 15–22, find a vector representation for the surface., , (b), , (a), , 15. The plane that passes through the point (2, 1, �3) and contains the vectors 2i � j � k and i � 2j � k, , z, , z, , 16. The plane 2x � 3y � z � 6, 17. The lower half of the sphere x 2 � y 2 � z 2 � 1, 18. The upper half of the ellipsoid 9x 2 � 4y 2 � 36z 2 � 36, y, , y, , 19. The part of the cylinder x 2 � y 2 � 4 between z � �1 and, z�3, , x, , x, (c), , 20. The part of the cylinder 9y 2 � 4z 2 � 36 between x � 0 and, x�3, , (d), z, , z, , 21. The part of the paraboloid z � 9 � x 2 � y 2 inside the cylinder x 2 � y 2 � 4, 22. The part of the plane z � x � 2 that lies inside the cylinder, x 2 � y2 � 1, y, , y, , x, , In Exercises 23–26, find a vector equation for the surface, obtained by revolving the graph of the function about the indicated axis. Graph the surface., , x, , 23. y � 1x,, �x, , 24. y � e ,, , In Exercises 5–8, find an equation in rectangular coordinates,, and then identify and sketch the surface., 6. r(u, √) � (u 2 � √2)i � uj � √k, 8. r(u, √) � 2 cos √ cos ui � 2 cos √ sin uj � 3 sin √k, , 0, , u, , x, , 1;, , x-axis, , 0, , y, , 3;, , �p, , z, , p;, , y-axis, z-axis, , 28. r(u, √) � ui � (u � √ )j � √k;, 2, , graph the surface represented by the vector function., , 10. r(u, √) � ui � (√ � 1)j � (√3 � √)k;, �2 √ 1, , 0, , 27. r(u, √) � (u � √)i � (u � √)j � √2k;, , cas In Exercises 9–14, use a computer algebra system (CAS) to, , 9. r(u, √) � (u � √)i � (u � √)j � (u 2 � √2)k;, �1 √ 1, , x-axis, , In Exercises 27–32, find an equation of the tangent plane to the, parametric surface represented by r at the specified point., , 2, , √, , 4;, , 25. x � 9 � y ,, 26. y � cos z,, , 0, , x, , 2, , 5. r(u, √) � (u � √)i � 3√j � (u � √)k, 7. r(u, √) � 3 sin ui � 2 cos uj � √k,, , 0, , 2, , (2, 5, 1), , 29. r(u, √) � u cos √i � 2u sin √j � u k;, 2, , �1, 1,, , 11. r(u, √) � cos u sin √i � sin u sin √j � (1 � cos √)k;, 0 u 2p, 0 √ 2p, , u, , (2, 0, 1), u � 1,, , √�p, , 1,, 30. r(u, √) � cos u sin √i � sin u sin √j � cos √k;, p, √�, 4, , u�, , 31. r(u, √) � ue√ i � √euj � u√k;, , u � 0,, , √ � ln 2, , 32. r(u, √) � u√i � u ln √j � √k;, , u � 1,, , √�1, , 12. r(u, √) � √ cos u sin √i � √ sin u sin √j � u cos √k;, 0 u 2p, 0 √ p, , In Exercises 33–40, find the area of the surface., , 13. r(u, √) � √ cos ui � √ sin uj � √ k;, 0 √ 1, , 33. The part of the plane r(u, √) � (u � 2√ � 1)i �, (2u � 3√ � 1)j � (u � √ � 2)k; 0 u 1, 0, , 2, , 0, , u, , 2p,, , V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login., , p, ,, 2, , √, , 2

Page 23 :

1290, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , 34. The part of the plane 2x � 3y � z � 1 that lies above the, rectangular region [1, 2] [1, 3], 35. The part of the plane z � 8 � 2x � 3y that lies inside the, cylinder x 2 � y 2 � 4, 36. The part of the paraboloid r(u, √) � u cos √i �, u sin √j � u 2k; 0 u 3, 0 √ 2p, , 45. In Section 5.4 we defined the area of the surface of revolution obtained by revolving the graph of a nonnegative, smooth function f on [a, b] about the x-axis as, S � 2p, , 38. The part of the sphere r(u, √) � a sin u cos √i �, a sin u sin √j � a cos uk that lies in the first octant, , Use Equation (1) to derive this formula., 46. If the circle with center at (a, 0, 0) and radius b, where, 0 � b � a, in the xz-plane is revolved about the z-axis,, we obtain a torus represented parametrically by, x � (a � b cos √)cos u, , 39. The surface r(u, √) � sin u cos √i � sin u sin √j � uk;, 0 u p, 0 √ 2p, 40. The part of the surface r(u, √) � u i � u√j � √ k;, 0 u 1, 0 √ 2, 1, 2, , x2, a2, , �, , y2, b2, , �, , z2, c2, , y � (a � b cos √)sin u, , 2, , z � b sin √, , cas 41. a. Show that the vector equation r(u, √) � a sin u cos √i �, , b sin u sin √j � c cos uk, where 0 u, 0 √ 2p, represents the ellipsoid, , f(x)21 � [ f ¿(x)]2 dx, , a, , 37. The part of the cone r(u, √) � u cos √i � u sin √j � uk;, 1 u 2, 0 √ p2, , 2, , 冮, , b, , p and, , with parametric domain D � {(u, √) 冟 0 u 2p,, 0 √ 2p}. (See the figure below.) Find the surface, area of the torus., z, , �1, , b. Use a CAS to graph the ellipsoid with a � 3, b � 4, and, c � 5., c. Use a CAS to find the approximate surface area of the, ellipsoid of part (b)., , u, , cas 42. a. Show that the vector equation r(u, √) � a sin u cos √i �, 3, , a sin3 u sin3 √j � a cos3 uk, where 0 u p and, 0 √ 2p, represents the astroidal sphere, x 2>3 � y 2>3 � z 2>3 � a 2>3., b. Use a CAS to graph the astroidal sphere with a � 1., c. Find the area of the astroidal sphere with a � 1., , 43. Find the area of the part of the cone z � 2x 2 � y 2 that is, cut off by the cylinder x 2 � (y � 1)2 � 1., 44. In Section 13.7 we showed that the tangent plane to the, graph S of a function f(x, y) at the point (a, b, f(a, b)) is, given by the equation, z � f(a, b) � fx(a, b)(x � a) � fy(a, b)(y � b), (See Equation (4) in Section 13.7.) Show that parametrizing, S by r(x, y) � xi � yj � f(x, y)k yields the same tangent, plane., , 15.7, , y, , 3, , (x, y, z), x (a, 0, 0), , In Exercises 47 and 48, determine whether the statement is true, or false. If it is true, explain why. If it is false, explain why or, give an example that shows it is false., 47. The surface described by r(u, √) � u cos √i � u sin √j � uk,, where �2 u 2 and 0 √ 2p, is smooth., 48. If r(u, √) � 2 sin u cos √i � 2 sin u sin √j � 2 cos uk,, where 0 u p2 and 0 √ p2 , then, p>2, , 冮 冮, 0, , p>2, , 冟 ru, , r√ 冟 du d√ � 2p, , 0, , Surface Integrals, Surface Integrals of Scalar Fields, As we saw in Section 14.1, the mass of a thin plate lying in a plane region can be, found by evaluating the double integral 兰兰R s(x, y) dA, where s(x, y) is the mass density of the plate at any point (x, y) in R. Now, instead of a flat plate, let’s suppose that

Page 24 :

15.7, , Surface Integrals, , 1291, , we have a plate that takes the form of a curved surface. How do we determine the mass, of this plate?, For simplicity, let’s suppose that the thin plate has the shape of the surface S that, is the graph of a continuous function t of two variables defined by z � t(x, y). To further simplify our discussion, suppose that the domain of t is a rectangular region, R � {(x, y) 冟 a x b, c y d}. A typical surface is shown in Figure 1., , z, Sij, , z = t(x, y), S, , 0, a, , c, d, , FIGURE 1, A thin plate that takes the shape of, a surface S defined by z � t(x, y), , y, , b, , Rij, , x, , Let the mass density of the plate at any point on S be s(x, y, z), where s is a nonnegative continuous function defined on an open region containing S, and let P � {Rij}, be a partition of R into N � mn subrectangles. Corresponding to each subrectangle, Rij, there is a part of S, Sij, that lies directly above Rij with area ⌬Sij. Then, ⌬Sij � 2[tx(x i, yj)]2 � [ty(x i, yj)]2 � 1 ⌬A, , (1), , where (x i, yj) is the corner of Rij closest to the origin and ⌬A is the area of Rij. If m, and n are large so that the dimensions of Rij are small, then the continuity of t and s, implies that s(x, y, z) does not differ appreciably from s(x i, yj, t(x i, yj)) . Therefore,, the mass of the part of the plate that lies on S and directly above Rij is, ⌬m ij ⬇ s(x i, yj, t(x i, yj)) ⌬Sij, , Constant mass density ⴢ surface area, , Using Equation (1), we see that the mass of the plate is approximately, m, , n, , 2, 2, a a s(x i, yj, t(x i, yj))2[tx(x i, yj)] � [ty(x i, yj)] � 1 ⌬A, i�1 j�1, , The approximation should improve as m and n approach infinity. This suggests that we, define the mass of the plate to be, m, , n, , lim a a s(x i, yj, t(x i, yj))2[tx(x i, yj)]2 � [ty(x i, yj)]2 � 1 ⌬A, n, m→⬁, i�1 j�1, , Using the definition of the double integral, we see that the required mass, m, is, m�, , 冮冮 s(x, y, z) dS � 冮冮 s(x, y, t(x, y))2[t (x, y)], , 2, , x, , S, , � [ty(x, y)]2 � 1 dA (2), , R, , if we assume that both tx and ty are continuous on R., The integral that appears in Equation (2) is a surface integral. More generally,, we can define the surface integral of a function f over nonrectangular regions as, follows.

Page 25 :

1292, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , DEFINITION Surface Integral of a Scalar Function, Let f be a function of three variables defined in a region in space containing a, surface S. The surface integral of f over S is, , 冮冮, , m, , n, , f(x, y, z) dS � lim a a f(x i, yj, t(x i, yj)) ⌬Sij, n, m→⬁, i�1 j�1, , S, , We also have the following formulas for evaluating a surface integral depending on, the way S is defined., , THEOREM 1 Evaluation of Surface Integrals, (for Surfaces That Are Graphs), 1. If S is defined by z � t(x, y) and the projection of S onto the xy-plane is R, (Figure 2a), then, , 冮冮 f(x, y, z) dS � 冮冮 f(x, y, t(x, y))2[t (x, y)], , 2, , x, , S, , � [ty(x, y)]2 � 1 dA, , (3), , R, , 2. If S is defined by y � t(x, z) and the projection of S onto the xz-plane is R, (Figure 2b), then, , 冮冮 f(x, y, z) dS � 冮冮 f(x, t(x, z), z)2[t (x, z)], , 2, , x, , S, , � [tz (x, z)]2 � 1 dA, , (4), , R, , 3. If S is defined by x � t(y, z) and the projection of S onto the yz-plane is R, (Figure 2c), then, , 冮冮 f(x, y, z) dS � 冮冮 f(t(y, z), y, z)2[t (y, z)], , 2, , y, , S, , � [tz (y, z)]2 � 1 dA, , (5), , R, , z, , z, , z, y = t(x, z), , R, , z = t(x, y), , S, , S, , R, , S, y, , y, , R, , y, , x, , x, , x, , (a), , (b), , (c), , x = t (y, z), , FIGURE 2, The surfaces S and their projections onto the coordinate planes, , Note, , If we take f(x, y, z) � 1, then each of the formulas gives the area of S., , EXAMPLE 1 Evaluate 兰兰S x dS, where S is the part of the plane 2x � 3y � z � 6, that lies in the first octant.

Page 26 :

15.7, , Surface Integrals, , 1293, , Solution The plane S is shown in Figure 3a, and its projection onto the xy-plane, is shown in Figure 3b. Using Equation (3) with f(x, y, z) � x and z � t(x, y) �, 6 � 2x � 3y, we have, , 冮冮 f(x, y, z) dS � 冮冮 x dS � 冮冮 x2[t (x, y)], , 2, , x, , S, , S, , R, , 冮冮 x2(�2), , �, , � [ty(x, y)]2 � 1 dA, , 2, , � (�3)2 � 1 dA � 114, , R, , 3, , � 114, , 冮冮, 0, , 冮 CxyD, 0, , � 114, , 冮, , 3, , 0, , R, , 2�(2>3)x, , x dy dx, , View R as y-simple., , 0, , 3, , � 114, , 冮冮 x dA, , y�2�(2>3)x, y�0, , a2x �, , dx, , 3, 2 2, 2, x b dx � 114 cx 2 � x 3 d � 3 114, 3, 9, 0, , y, , z, 6, , 2, , 2x � 3y � z � 6, , 2x � 3y � 6, 1, , R, , 2, , R, , y, , 3, , 1, , 2, , 3, , x, , x, (a) The surface S, , (b) The projection R of S onto the xy-plane, viewed as y-simple, , FIGURE 3, , EXAMPLE 2 Find the mass of the surface S composed of the part of the paraboloid, y � x 2 � z 2 between the planes y � 1 and y � 4 if the density at a point P on S is, inversely proportional to the distance between P and the axis of symmetry of S., Solution The surface S is shown in Figure 4a, and its projection onto the xz-plane is, shown in Figure 4b. Using Equation (4) with f(x, y, z) � s(x, y, z) � k(x 2 � z 2)�1>2,, where k is the constant of proportionality and y � t(x, z) � x 2 � z 2, we have, m�, , 冮冮 s(x, y, z) dS � 冮冮 k(x, S, , 2, , � z 2)�1>2 dS, , S, , 冮冮 (x, , �k, , 2, , � z 2)�1>2 2[tx(x, z)]2 � [tz(x, z)]2 � 1 dA, , 2, , � z 2)�1>2 2(2x)2 � (2z)2 � 1 dA, , 2, , � z 2)�1>2 24x 2 � 4z 2 � 1 dA, , R, , 冮冮 (x, , �k, , R, , 冮冮 (x, , �k, , R

Page 27 :

1294, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, z, , z, y�x �z, 2, , 2, , R, , R, y�4, , 2, , 4, , x, , FIGURE 4, , 1, , 1, , 2, , x, , y, , y�1, , (b) The projection R of S onto the xz-plane, , (a) The surface S, , Changing to polar coordinates, x � r cos u and z � r sin u, we obtain, 2p, , m�k, , 2, , 冮 冮 a r b24r, 0, , � 2k, , 1, , 2p, , 2, , � 1 r dr du � 2k, , 1, , 冮, , 0, , 2p, , 2, , 冮 冮 2r, 0, , 2, , �, , 1, , r�2, r, 1, c 2r 2 � 14 � ln ` r � 2r 2 � 14 ` d, du, 2, 8, r�1, , � kc 117 �, , 1, 1, 4 � 117, 15 � lna, bd, 2, 4, 2 � 15, , � kpc2117 � 15 �, , 1 12 2 2 dr du, Use Formula 37 from, the Table of Integrals., , 2p, , 冮, , du, , 0, , 1, 4 � 117, lna, bd, 2, 2 � 15, , Parametric Surfaces, If a surface S is represented by a vector equation, r(u, √) � x(u, √)i � y(u, √)j � z(u, √)k, with parameter domain D, then an element of surface area is given by, 冟 ru(u, √), , r√(u, √) 冟 dA, , as we saw in Section 15.6. This leads to the following formula for evaluating a surface, integral in which the surface is defined parametrically., , THEOREM 2 Evaluation of Surface Integrals (for Parametric Surfaces), If f is a continuous function in a region that contains a smooth surface S with, parametric representation, r(u, √) � x(u, √)i � y(u, √)j � z(u, √)k, , (u, √) 僆 D, , then the surface integral of f over S is, , 冮冮 f(x, y, z) dS � 冮冮 f(r(u, √)) 冟 r, , u, , S, , D, , where f(r(u, √)) � f(x(u, √), y(u, √), z(u, √))., , r√ 冟 dA, , (6)

Page 28 :

15.7, , Surface Integrals, , 1295, , Note You can show that if S is the graph of a function z � t(x, y), then Equation (3), follows from Equation (6) by putting r(u, √) � ui � √j � t(u, √)k. (See Exercise 46.), , EXAMPLE 3 Evaluate, , x�y, , 冮冮 12z � 1 dS,, , where S is the surface represented by, , S, , r(u, √) � (u � √)i � (u � √)j � (u 2 � √2)k, where 0, Solution, , u, , 1 and 0, , √, , 2., , We first find, ru(u, √) � i � j � 2uk, r√(u, √) � i � j � 2√k, i, r√ � † 1, 1, , ru, , j k, 1 2u †, �1 2√, , � 2[(u � √)i � (u � √)j � k], so, , 冟 ru, , r√ 冟 � 22(u � √)2 � (u � √)2 � 1 � 222u 2 � 2√2 � 1, , Therefore,, , 冮冮, S, , x�y, dS �, 12z � 1, , 2, , 冮冮, 0, , (u � √) � (u � √), , 1, , 22(u 2 � √2) � 1, , 0, , 2, , �4, , 冮冮, 0, , √ du d√, , 冮 Cu√D, 0, , �4, , 1, , 0, , 2, , �4, , 冮, , ⴢ 222u 2 � 2√2 � 1 du d√, , 0, , 2, , u�1, u�0, , d√, 2, , √ d√ � 2√2 ` � 8, 0, , Oriented Surfaces, , S, , n, –n, , FIGURE 5, Unit inner and outer normals to, an (orientable) closed surface S, , One of the most important applications of surface integrals involves the computation, of the flux of a vector field across an oriented surface. Before explaining the notion of, flux, however, we need to elaborate on the meaning of orientation., A surface S is orientable or two-sided if it has a unit normal vector n that varies, continuously over S, that is, if the components of n are continuous at each point (x, y, z), on S. Closed surfaces (surfaces that are boundaries of solids) such as spheres are examples of orientable surfaces. There are two possible choices of n for orientable surfaces:, the unit inner normal that points inward from S and the unit outer normal that points, outward from S (see Figure 5). By convention, however, the positive orientation for, a closed surface S is the one for which the unit normal vector points outward from S., An example of a nonorientable surface is the Möbius strip, which can be constructed, by taking a long, rectangular strip of paper, giving it a half-twist, and then taping the short, edges together to produce the surface shown in Figure 6. If you take a unit normal n starting at P (see Figure 6), then you can move it along the surface in such a way that upon, returning to the starting point (and without crossing any edges), it will point in a direction precisely opposite to its initial direction. This shows that n does not vary continuously on a Möbius strip, and accordingly, the strip is not orientable.

Page 29 :

1296, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , n, , Start, P, , d, , FIGURE 6, The Möbius strip can be constructed, by using a rectangular strip of paper., , c, d b, , a, , b, , a c, , Surface Integrals of Vector Fields, Suppose that F is a continuous vector field defined in a region R in space. We can think, of F(x, y, z) as giving the velocity of a fluid at a point (x, y, z) in R, and S as a smooth,, oriented surface lying in R. If S is flat and F is a constant field, then the flux, or rate, of flow (volume of fluid crossing S per unit time), is equal to, , F, F•n, , F ⴢ n A(S), , n, S, , FIGURE 7, If S is flat and F is constant, then, the flux is equal to the volume, of the prism., z, , z � t (x, y), S, c, , a, b, , d, y, , R, , (the normal component of F with respect to S times the area of S). Geometrically, the, flux is given by the volume of fluid in the prism in Figure 7., More generally, suppose that S is the graph of a function of two variables defined, by z � t(x, y), where, for simplicity, we assume that the domain of t is a rectangular, region R � {(x, y) 冟 a x b, c y d}. (See Figure 8.) Let P � {Rij} be a partition of R into N � mn subrectangles. Corresponding to each subrectangle Rij there is, the part of S that lies directly above Rij with area ⌬Sij. As in Section 14.5, let (x i, yj) be, the corner of Rij closest to the origin, and let (x i, yj, t(x i, yj)) be the point directly above, it, as shown in Figure 9. Let n ij denote the unit normal vector to S at (x i, yj, t(x i, yj))., If m and n are large so that the dimensions of Rij are small, then the continuity of F, implies that F(x, y, z) does not differ appreciably from F(x i, yj, t(x i, yj)) on Rij., Furthermore, the continuity of t implies that Sij may be approximated by Tij, the, parallelogram that is part of the tangent plane to S at the point (x i, yj, t(x i, yj)) lying, directly above Rij. But the flux of F across (the flat) Tij is approximately, , x, , F(x i, yj, t(x i, yj)) ⴢ n ij(⌬Tij), , FIGURE 8, A smooth surface S defined by, z � t(x, y) for (x, y) in R, , where ⌬Tij is the area of Tij. Since ⌬Tij ⬇ ⌬Sij, we see that the flux of F across S may, be approximated by the sum, m, , nij, (xi, yj, t(xi, yj)), , n, , a a F(x i, yj, t(x i, yj)) ⴢ n ij ⌬Sij, , F, , i�1 j�1, , m, , Sij, , n, , � a a F(x i, yj, t(x i, yj)) ⴢ n ij2[tx(x i, yj)]2 � [ty(x i, yj)]2 � 1 ⌬A, , Tij, , i�1 j�1, , This last equality follows upon using Equation (1). We can expect that the approximation will get better as the partition P becomes finer. This observation leads to the following definition., , DEFINITION Surface Integral of a Vector Field, (xi, yj), Rij, , FIGURE 9, , Let F be a continuous vector field defined in a region containing an oriented surface S with unit normal vector n. The surface integral of F across S in the, direction of n is, , 冮冮 F ⴢ dS � 冮冮 F ⴢ n dS �, S, , S, , m, , lim, , n, , a a F(x i, yj, f(x i, yj)) ⴢ n ij ⌬Sij, , m, n→⬁ i�1 j�1

Page 30 :

15.7, , Surface Integrals, , 1297, , Thus, the surface integral (also called flux integral) of a vector field F across an, oriented surface S is the integral of the normal component of F over S. If the fluid has, density r(x, y, z) at (x, y, z), then the flux integral, , 冮冮 rF ⴢ n dS, S, , gives the mass of the fluid flowing across S per unit time., To obtain a formula for finding the flux integral in terms of t(x, y), recall from, Section 13.6 that the normal to the surface z � t(x, y) is given by §G, where, G(x, y, z) � z � t(x, y). Therefore, the unit normal to S is, n�, , �tx(x, y)i � ty(x, y)j � k, §G(x, y, z), �, 冟§G(x, y, z) 冟, 2[tx(x, y)]2 � [ty(x, y)]2 � 1, , Furthermore, in Section 14.5 we showed that the “element of area” dS is given by, dS � 2[tx(x, y)]2 � [ty(x, y)]2 � 1 dA, so, F ⴢ [�tx(x, y)i � ty(x, y)j � k], , 冮冮 F ⴢ n dS � 冮冮 2[t (x, y)], , 2, , S, , D, , �, , x, , � [ty(x, y)] � 1, 2, , ⴢ 2[tx(x, y)]2 � [ty(x, y)]2 � 1 dA, , 冮冮 F ⴢ [�t (x, y)i � t (x, y)j � k] dA, x, , y, , D, , where D is the projection of S onto the xy-plane., If F(x, y, z) � P(x, y, z)i � Q(x, y, z)j � R(x, y, z)k, then we can write, , 冮冮 F ⴢ n dS � 冮冮 (�Pt, , x, , S, , � Qty � R) dA, , D, , THEOREM 3 Evaluation of Surface Integrals (for Graphs), If F � Pi � Qj � Rk is a continuous vector field in a region that contains a, smooth oriented surface S given by z � t(x, y) and D is its projection onto the, xy-plane, then, , 冮冮 F ⴢ dS � 冮冮 (�Pt, , x, , S, , � Qty � R) dA, , (7), , D, , Before looking at the next example, we note the following property of surface integrals: If S � S1 傼 S2 傼 p 傼 Sn, where each of the surfaces is smooth and intersect, only along their boundaries, then, , 冮冮 F ⴢ dS � 冮冮 F ⴢ dS � p � 冮冮 F ⴢ dS, S, , S1, , Sn, , EXAMPLE 4 Evaluate 兰兰S F ⴢ dS, where F(x, y, z) � xi � yj � zk and S is the surface that is composed of the part of the paraboloid z � 1 � x 2 � y 2 lying above the, xy-plane and the disk D � {(x, y) 冟 0 x 2 � y 2 1}.

Page 31 :

1298, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, z, , S1, z = 1 – x 2 – y2, S2, , Solution The (closed) surface S together with a few vectors from the vector field F, is shown in Figure 10. Writing the equation of the surface S1 in the form t(x, y) �, 1 � x 2 � y 2, we find that tx � �2x and ty � �2y. Observe that the projection of S onto, the xy-plane is D � {(x, y) 冟 0 x 2 � y 2 1}. Also, P(x, y, z) � x, Q(x, y, z) � y, and, R(x, y, z) � z. So using Equation (7), we obtain, , 冮冮 F ⴢ dS � 冮冮 (�Pt, , x, , y, , S1, , � Qty � R) dA, , D, , x, , �, , FIGURE 10, The part of the paraboloid, z � 1 � x 2 � y 2 that lies above, the xy-plane and is oriented so that, the unit normal vector n points, upward. The unit normal for the, disk D � S2 points downward., , 冮冮 [�x(�2x) � y(�2y) � z] dA, D, , �, , 冮冮 (2x, , 2, , � 2y 2 � z) dA, , 2, , � 2y 2 � (1 � x 2 � y 2)] dA, , D, , �, , 冮冮 [2x, , z � 1 � x 2 � y2, , D, , �, , 冮冮 (1 � x, , 2, , � y 2) dA, , D, , 2p, , �, , 1, , 冮 冮 (1 � r )r dr du, 2, , 0, , �, , 冮, , Use polar coordinates., , 0, , 2p, , 0, , r�1, 1, 1, c r 2 � r 4d, du �, 2, 4, r�0, , 冮, , 0, , 2p, , 3, 3, du � p, 4, 2, , Next, observe that the normal for the surface S2 is n � �k. (Remember that the normal for a closed surface, by convention, points outward.) So we have, , 冮冮 F ⴢ dS � 冮冮 F ⴢ (�k) dS � 冮冮 (�z) dA � 冮冮 0 dA � 0, S2, , S2, , D, , D, , because z � 0 on S2. Therefore,, , 冮冮 F ⴢ dS � 冮冮 F ⴢ dS � 冮冮 F ⴢ dS � 2 p � 0 �, 3, , S, , S1, , 3p, 2, , S2, , Notes, 1. If the vector field F of Example 4 describes the velocity of a fluid flowing, through the paraboloidal surface S, then the integral 兰兰S F ⴢ n dS that we have, just evaluated tells us that the fluid is flowing out through S at the rate of 3p>2, cubic units per unit time., 2. In Example 4, if we had wanted the paraboloid to be oriented so that the normal, pointed downward, then we would simply have picked the normal to be �n. In, this case the fluid flows into S at the rate of 3p>2 cubic units per unit time., , Parametric Surfaces, If an oriented surface S is a smooth surface represented by a vector equation, r(u, √) � x(u, √)i � y(u, √)j � z(u, √)k

Page 32 :

15.7, , Surface Integrals, , 1299, , with parameter domain D, then the normal to S is, n�, , ru, 冟 ru, , r√, r√ 冟, , Therefore,, , 冮冮 F ⴢ dS � 冮冮 F ⴢ n dS � 冮冮 F ⴢ 冟 r, , ru, , S, , S, , �, , u, , S, , 冮冮 cF(r(u, √)) ⴢ 冟 r, , ru, u, , D, , �, , r√, dS, r√ 冟, , 冮冮 F(r(u, √)) ⴢ (r, , u, , r√, d 冟 ru, r√ 冟, , r√ 冟 dA, , r√) dA, , D, , THEOREM 4 Evaluation of Surface Integrals of a Vector Field, (for Parametric Surfaces), If F is a continuous vector field in a region that contains a smooth, oriented surface S with parametric representation, r(u, √) � x(u, √)i � y(u, √)j � z(u, √)k, , (u, √) 僆 D, , then the surface integral of f over S is, , 冮冮 F ⴢ dS � 冮冮 F(r(u, √)) ⴢ (r, , u, , S, , r√) dA, , (8), , D, , where, F(r(u, √)) � F(x(u, √), y(u, √), z(u, √)), , EXAMPLE 5 Find the flux of the vector field F(x, y, z) � yi � xj � 2zk across the, unit sphere x 2 � y 2 � z 2 � 1., Solution, , The unit sphere has parametric representation, r(u, √) � sin u cos √i � sin u sin √j � cos uk, , with parameter domain D � {(u, √) 冟 0 u p, 0 √, Example 10 in Section 15.6 and taking a � 1, we find, ru, , 2p}. Proceeding as in, , r√ � sin2 u cos √i � sin2 u sin √j � sin u cos uk, , Therefore,, F(r(u, √)) ⴢ (ru, , r√) � (sin u sin √i � sin u cos √j � 2 cos uk), ⴢ (sin2 u cos √i � sin2 u sin √j � sin u cos uk), � sin3 u sin √ cos √ � sin3 u cos √ sin √ � 2 cos2 u sin u, � 2(sin3 u sin √ cos √ � cos2 u sin u)

Page 33 :

1300, , Chapter 15 Vector Analysis, , Using Equation (8), the flux across the sphere is, , 冮冮 F ⴢ dS � 冮冮 F(r(u, √)) ⴢ (r, , r√) dA, , u, , S, , D, , 2p, , �2, , 冮 冮, 0, , �2, , 冮, , p, , (sin3 u sin √ cos √ � cos2 u sin u) du d√, , 0, , p, , sin3 u du, , 0, , 冮, , 2p, , sin √ cos √ d√ � 2, , 0, , 冮, , p, , cos2 u sin u du, , 0, , 冮, , 2p, , d√, , 0, , The first term on the right is equal to zero because, , Historical Biography, , 冮, , 2p, , sin √ cos √ d√ �, , 0, , 1 2 2p, sin √ ` � 0, 2, 0, , so, , 冮冮 F ⴢ dS � 2冮, , 2, , cos u sin u du, , 0, , S, , Bettmann/Corbis, , p, , 冮, , 2p, , d√, , 0, , p, 1, � 2a� cos3 ub ` ⴢ 2p, 3, 0, , CHARLES-AUGUSTIN DE COULOMB, , �, , (1736–1806), Born to a wealthy family, Charles-Augustin, de Coulomb spent his early years in, Angoulême in southwestern France. His, family later moved to Paris, where he, attended good schools and received a solid, education. In 1760, Coulomb entered the, two-year military engineering program at, the Ecole de Genie at Mézières. At the conclusion of those studies, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the, infantry, where he served in the engineering corps. For the next twenty years, Coulomb served in a variety of posts and, was involved in a wide range of military, engineering projects. From 1764 to 1772, Coulomb was put in charge of constructing, the new Fort Bourbon in Martinique in the, West Indies. Upon his return to France, he, started writing works on applied mechanics, and he began publishing important, works in 1773. This period culminated with, his work on friction, Theorie des machines, simples, which won him a prize in 1781. This, recognition changed the direction of his, life. He was elected to the mechanics section of the Academie des Sciences, and he, focused on his work as a physicist instead, of engineering. Between 1785 and 1791 he, wrote seven important treatises on electricity and magnetism, in which he developed the theory of attraction and repulsion between electrical charges that is now, known as Coulomb’s Law., , 8p, 3, , We have used an example involving fluid flow to illustrate the concept of the surface integral of a vector field. But these integrals have wider applications in the physical sciences. For example, if E is the electric field induced by an electric charge of q, coulombs located at the origin of a three-dimensional coordinate system, then by, Coulomb’s Law (Example 4 in Section 15.1),, E�, , q, r, ⴢ, 4pe0 冟 r 冟3, , where e0 is a constant called the permittivity of free space. If S is a sphere of radius r, centered at the origin, then the surface integral, , 冮冮 E ⴢ n dS, S, , is the flux of E passing through S., Yet another application of surface integrals can be found in the study of heat flow., Suppose that the temperature at a point (x, y, z) in a homogeneous body is T(x, y, z)., Empirical results suggest that heat will flow from points at higher temperatures to those, at lower temperatures. Since the temperature gradient §T points in the direction of, maximum increase of the temperature, we see that the flow of heat can be described, by the vector field, q � �k §T, where k is a constant of proportionality known as the thermal conductivity of the body., The rate at which heat flows across a surface S in the body is given by the surface, integral, , 冮冮 q ⴢ n dS � �k冮冮 §T ⴢ n dS, S, , S

Page 34 :

15.7, , Surface Integrals, , 1301, , EXAMPLE 6 Rate of Flow of Heat Across a Sphere The temperature at a point, P(x, y, z) in a medium with thermal conductivity k is inversely proportional to the distance between P and the origin. Find the rate of flow of heat across a sphere S of radius, a, centered at the origin., Solution, , We have, T(x, y, z) �, , c, 2x � y 2 � z 2, 2, , where c is the constant of proportionality. Then the flow of heat is, q � �k §T � �kc�, �, , cx, (x � y � z ), 2, , ck, (x � y 2 � z 2)3>2, 2, , 2, , 2 3>2, , cy, , i�, , (x � y � z ), 2, , 2, , 2 3>2, , j�, , cz, (x � y 2 � z 2)3>2, 2, , kd, , (xi � yj � zk), , The outward unit normal to the sphere x 2 � y 2 � z 2 � a 2 at the point (x, y, z) is, n�, , 1, (xi � yj � zk), a, , So the rate at which heat flows across S is, , 冮冮 q ⴢ n dS � 冮冮 (x, S, , S, , �, , ck, a, , ck, 2, , �y �z ), 2, , 冮冮 2x, S, , �, �, , 15.7, , ck, a2, ck, a2, , 1, (xi � yj � zk) ⴢ c (xi � yj � zk)d dS, a, , 1, 2, , � y2 � z2, , 冮冮 dS, , dS, , Since x 2 � y 2 � z 2 � a 2 on S, , S, , A(S) �, , ck, a2, , (4pa 2) � 4pck, , CONCEPT QUESTIONS, , 1. a. Define the surface integral of a scalar function f over a, surface that is the graph of a function z � f(x, y)., b. How do you evaluate the integral of part (a)?, c. How do you evaluate the surface integral if the surface is, represented by a vector function r(u, √)?, 2. What is an orientable surface? Give an example of a surface, that is not orientable., , 15.7, , 2 3>2, , 3. a. Define the surface (flux) integral of a vector field F over, an oriented surface S with a unit normal n., b. How do you evaluate the surface integral if the surface is, the graph of a function z � t(x, y)?, c. How do you evaluate the surface integral if the surface is, represented by the vector function r(u, √)?, , EXERCISES, , In Exercises 1–14, evaluate 兰兰S f(x, y, z) dS., 1. f(x, y, z) � x � y; S is the part of the plane, 3x � 2y � z � 6 in the first octant, V Videos for selected exercises are available online at www.academic.cengage.com/login., , 2. f(x, y, z) � xy; S is the part of the plane, 2x � 3y � z � 6 in the first octant

Page 35 :