Page 1 :

224, , CHAPTER 5. COMMUTATIVE RINGS, , integers modulo will be shown to form a commutative ring. This is an example, of an important procedure by which new rings can be constructed-the use of a, congruence relation on a given ring. The notion of a factor group will be extended to, that of a factor ring. In the construction of factor rings, the role of normal subgroups, in forming factor groups will be played by subsets called "ideals." Examples are, in and, in, Then the notions of prime number and irreducible, polynomial motivate the definition of a "prime ideal," which allows us to tie together, a number of facts about integers and polynomials. In Section 5.4 we construct, quotient fields for integral domains, and thus characterize all subrings of fields., , n, , nZ Z (f(x)) F[x]., 5.1, , Commutative Rings ; Integral Domains, , In Chapter 1 , we began our study of abstract algebra by concentrating on one of the, most familiar algebraic structures, the set of integers. In both and we have, two basic operations-addition and multiplication. Subtraction and division (when, possible) are defined in terms of these two operations. After studying groups in, Chapter where we have only one operation to deal with, we returned to systems, with two operations when we worked with fields and polynomials in Chapter 4., We will now undertake a systematic study of systems in which there are two, operations that generalize the familiar operations of addition and multiplication., The examples you should have in mind are these: the set of integers the set of, integers modulo any field (in particular the set of rational numbers and the, set of real numbers); the set, of all polynomials with coefficients in a field, The axioms we will use are the same as those for a field, with one crucial exception., We have dropped the requirement that each nonzero element has a multiplicative, inverse (see Definition 4. 1 . 1 ), in order to include integers and polynomials in the, class of objects we want to study. Because we are now considering, operations, at the same time, rather than studying one operation at a time, we need to have a, connection between the operations; the distributive laws accomplish this., , Z Zn, , 3,, , R, , n;, , FF[x], , Z;, , Q, , Zn, , F., , two, , Let, R, be, as, et, on, whi, c, h, two, bi, n, ary, operations, are, defined,, called, addition, and, multi, p, lication,, and, denoted, by, + and · . Then we say that the distribu, tive laws hold for addition and multip lication if, a . (b + c) a . b + a . c and (a + b) . c a . c + b . c, for all a, b, c E R., 5.1.1 Definition., , ==, , ==, , The distributive laws should be familiar, since we have already used them in, the set of integers (see Appendix A. l ) and in the definition of a field (see Defini, tion 4. 1 . 1 ). You should have met them in other examples too, since they hold for

Page 2 :

5. 1 . COMMUTATIVE RINGS; INTEGRAL DOMAINS, , 225, , the usual addition and multiplication of polynomials, as in Chapter 4, and also for, addition and multiplication of matrices., , Let, R, be, a, set, on, which, two, binary, operations, are, defined,, called, addition and multiplication and denoted by + and· respectively. Then R is called a, commutative ring with respect to these operations if the following properties hold:, R is an abelian group under addition;, multiplication is associative and commutative;, R has a multiplicative identity element;, the distributive laws hold., Since any commutative ring R determines an abelian group by just considering, the set R together with the single operation of addition, we call this group the, of R. Although we require that multiplication in R is, 5.1 .2 Definition., , (i), , (ii), , (iii), (iv), , underlying additive group, , commutative, the set of nonzero elements certainly need not define an abelian group, under multiplication., As you are learning the definition of a commutative ring, it may help to refer to, the expanded version of the definition, given below, in which all of the conditions are, written out explicitly. If you need to determine whether or not a set is a commutative, ring under two given operations, this expanded version gives you a "check list" of, conditions that you need to go through., , Let, R, be, a, set, on, which, two, binary, operations, are, defined,, denoted, by, +, and, ·, respectivel, y, ., That, is,, the, following, condition must be satisfied., Closure: /fa, b E R, then thesuma+b andtheproducta·b are well-defined, elements of R., Then properties, R is calledhold., a commutative ring with respect to these operations if the, following, Associative laws: For all a, b, c E R,, a + (b + c) (a + b) + c and a · (b . c) (a . b) . c ., Commutative laws : For all a, b E R,, a + b b + a and a · b b . a ., Distributive laws : For all a, b, c E R,, a . (b + c) a . b + a . c and (a + b) . c a . c + b . c ., 5.1 .2 / (Expanded version of Definition 5.1.2), , (i), , (ii), , ==, , ==, , (iii), , ==, , ==, , (iv), , ==, , ==

Page 3 :

226, , CHAPTER 5. COMMUTATIVE RINGS, , The, set, R, contains, an, element, 0, called an additive, identity element, such that for all a E R,, a + 0 a and 0 + a a ., The, set, R, contains, an, element, 1, called a multiplicative identity element, such, that for all a E R, a . 1 a and 1 · a a ., Additive inverses : For each a E R, the equations, a + 0 and + a 0, have a solution in R, called the additive inverse of a, and denoted by -a., We usually refer to the element 1 simply as the identity of the ring R. To avoid, any possible confusion with the additive identity 0, we will refer to 0 as the, of R. Since we do not require that 1 0, we could have R {O} , with, 0 + 0 0 and 0 . 0, We will refer to this ring as the, (v) Identity elements:, , ==, , ==, , ==, , ==, , (vi), , x ==, , x, , ==, , x, , element, ==, , ==, , ==, , �, , o., , zero ring., , zero, , A set with two binary operations that satisfy conditions (i)-(vi) of 5. 1 .2 /, with the, exception of the commutative law for multiplication, is called a ring. Although we, will not discuss them here, there are many interesting examples of noncommutative, rings. From your work in linear algebra, you should already be familiar with one, such example, the set of all 2 x 2 matrices over The standard rules for matrix, arithmetic provide all of the axioms for a commutative ring, with the exception of, the commutative law for multiplication. Although this is certainly an important, example worthy of study, we have chosen to work only with commutative rings,, with emphasis on integral domains, fields, and polynomial rings over them., We should note that in a commutative ring, either one of the distributive laws, implies the other. If you are checking the axioms for a ring, if you first prove that, multiplication is commutative, then you only need to check one of the distributive, laws. The definition requires you to check that there is an identity element. We, should point out that many textbooks do not include the existence of an identity, element in the definition of a commutative ring., Before giving some further examples of commutative rings, it is helpful to have, some additional information about them. Our observation that any commutative, ring is an abelian group under addition implies that the cancellation law holds for, addition. This proves part (a) of the next statement. Just as in the case of a field,, various uniqueness statements follow from Proposition 3. 1 .2., , R., , Let be a commutative ring, with elements, (a) If + == + then ==, (b) If + == 0 , then ==, , R, , a c b c, a b., a b, b -a., , a, b, c E R.

Page 4 :

227, , 5. 1 . COMMUTATIVE RINGS; INTEGRAL DOMAINS, , (c) If a + b == a for some a E, , R, then, , b == O., , In Proposition 4. 1 .3 the following properties were shown to hold for any field., The proof remains valid for any commutative ring. Note that (d) and (f) involve, connections between addition and multiplication. Their proofs make use of the, distributive law, since at the beginning it provides the only link between the two, operations., , R be a commutative ring, with elements a , E R., For all a E R, a, For all a E R, - ( -a ) a ., For all a , E R, (- ), , Let, (d), (e), (f), , b, , · 0 == O., ==, , b, , a · ( - b) == a · b., , We will follow the usual convention of performing multiplications before addi, tions unless parentheses intervene., Example 5. 1.1 ( Zn as a ring)., , In Section we listed the properties of addition and multiplication of congru, ence classes, which show that the set Zn of integers modulo n is a commutative, ring. From our study of groups we know that Zn is a factor group of Z (under, addition), and so it is an abelian group under addition. To verify that the neces, sary properties hold for multiplication, it is necessary to use the corresponding, properties for Z. We checked the distributive law in Section, It is worth, commenting on the proof of the associative law, to point out the crucial parts, of the proof. To check that the associative law holds for all, E Zn ,, we have, , 1.4, , [a]( [b] [e] ) == [a ][be] == [a(be)], , and, , 1.4 ., [a], [b], [c], ( [a ][b])[e] [ab] [e] == [ (ab)e] ,, ==, , and so these two expressions are equal because the associative law holds for, multiplication in Z. In effect, as soon as we have established that multiplica, tion is well-defined (Proposition, it is easy to show that the necessary, properties are inherited by the set of congruence classes. Note that is the, identity of Zn ., , 1.4.2),, , [1], , The rings Zn form a class of commutative rings that is a good source of, counterexamples. For instance, it provides an easy example showing that the, cancellation law may fail for multiplication. In the commutative ring Z 6 we, but =1=, have, , [2][3] == [4 ][3], [2] [4]. D

Page 5 :

228, , CHAPTER 5. COMMUTATIVE RINGS, , Example 5.1.2 (Polynomial rings)., , Let, , R be a commutative ring. We let T denote the set of infinite tuples, ai R, , i, ai, , such that E for all nonnegative integers and :j=. ° for only finitely, many tenns ai . We say that two infinite tuples are equal if and only if the, corresponding entries are equal. We introduce addition and multiplication in, as follows:, , T, , (ao, a I , a2 , . . . ) . (bo, hI , b2 , . . . ) = (co, C I , C2 , . . . , for Ck = Li + ai b ., Then (1, 0, 0, . . . ) is the identity of T, where 1 is the identity of R, and it can, be shown that T is a commutative ring under the above operations., We will follow the usual conventions of writing a for the element (a, 0, 0, . . . ), when a R, and x for the element (0, 1, 0, . . . ) . Then, x 2 (0, 1, 0, . . . ) · (0, 1, 0, . . . ), (0 . 0, 0 · 1 + 1 . 0, 0 · + 1 . 1 + . 0,, + 1 . + . 1 + . 0, . . . ), (0, 0, 1, 0, . . . ) ., Similarly, x 3 = (0, 0, 0, 1, 0, . . . ), and so on. We can then write, (ao, a I , . . . , am , 0, 0, . . . ) ao ( 1, 0, 0, . . . ) + a (0, 1, 0, . . . ), + a2 (0, 0, 1, . . . ) +m . .I . m, ao + a lx + . . . + am - I X - + am x ,, allowing us to use our previous notation R [x ] for the, R, x. We say that R is the, As, in Definition 4.1 . 4 , if n is the largest integer such that an :j=. 0, then we say, that the polynomial has, n,, and an is called the, of the polynomial. An element of the fonn a = (a, 0, 0, . . . ) is called a, We can, of course, use any symbol to represent the, tuple (0, 1, 0, . . . ) ., Once we know that R [x ] is a commutative ring, it is easy to work with polyno, mials in two indetenninates x and y . We can simply use R [x] as the coefficient, ring, and consider all polynomials over R [x ] in the indetenninate y . For ex, ample, by factoring out the appropriate tenns we have, 2x - 4xy + y 2 + xy 2 + x 2 y 2 3xy 3 + x 3 y 2 + 2x2 y 3 =, 2x + (-4x) y + (1 + x + x 2 + x 3 ) y2 + (-3x + 2x 2 ) y 3 ., The ring of polynomials in two indetenninates with coefficients in R is usually, denoted by R [x, y ], rather than by (R [x ])[y]., j =k, , ), , j, , ,, , E, , °.°, , °, , °, , °, , °, , °, , 1, , ring of polynomials, , over, , in the indeterminate, , coefficient ring., , degree, , leading coefficient, , constant polynomial ., , _, , D

Page 6 :

229, , COMMUTATIVE RINGS; INTEGRAL DOMAINS, , 5. 1 ., , The next proposition will make it easier for us to give examples, by giving, a simple criterion for testing subsets of known commutative rings to determine, whether they are also commutative rings. It seems easiest to just use to denote, the product, as we have already been doing. But you must remember that, this can represent any operation that merely behaves in certain ways like ordinary, multiplication., , ab, , a . b,, , Let, be, a, commutative, ring., subset, R of is called a subring, ofthe same, if it isidaentity, commutative, ri, n, g, under, the, addition, and, multi, p, lication, of, and, has, element as, Looking at the familiar sets Z Q R C, it is easy to check that each one, is a subring of the next larger set. If is any field, then in the polynomial ring, 5.1.3 Definition., S, , A, , S, , S, , S,, , S., , C, F, , C, , C, , F [x ], , we can identify the elements of F with the constant polynomials. This allows us to, think of F as a subring of F [x ] ., Let F and E be fields. If F is a subring of E , according to the above definition,, then we usually say (more precisely) that F is a subfield of E (as in Definition 4.4. 1 )., Of course, there may be other subrings of fields that are not necessarily subfields., Any subring is a subgroup of the underlying additive group of the larger ring, so the, two commutative rings must have the same zero element., If S is not the zero ring, then it contains the zero ring R == {o} as a proper subset., We note that the zero ring is not a subring of S, since it does not contain the identity, element 1 of S . This is in distinct contrast to the situation for groups., , Let, be, a, commutative, ring,, and, let, R be a subset of Then, is a subring of if and only if, R is closed under addition and multip lication;, if a E R, then -a E R;, R contains the identity of s., Proof, If R is a subring, then the closure axioms must certainly hold. Suppose that, + 0, where is the zero element, is the zero element of R . Then +, of so, 0, since the cancellation law for addition holds in If a E R and b, is the additive inverse of a in R, then a + b 0, so b -a by Proposition 3. 1 .2,, and this· shows that -a E R. Finally, the definition of a subring demands that the, 5.1.4 Proposition., R, S, , S, , S., , (i), , (ii), , (iii), , z, , z, , S,, , °, , z == z == z, , z ==, , ==, , S., , ==, , subring must have the same multiplicative identity, and therefore the identity of S, must belong to R., Conversely, suppose that the given conditions hold. The first condition shows, that condition (i) of 5. 1 .2 ' is satisfied. Conditions (ii)-(iv) of 5. 1 .2 ' are inherited, from S. The element 1 serves as an identity for R, and then - 1 E R by assumption,, so ° == 1 + ( - 1 ) E R since R is closed under addition. Thus conditions (v) and (vi), of 5. 1 .2 ' are also satisfied. D

Page 7 :

230, , CHAPTER 5. COMMUTATIVE RINGS, , Example 5.1.3 (Sub rings of Zn )., , If is any subring of Zn , then according to our definition [ 1 ] must belong to, Since is a subgroup of the underlying additive group of Zn , and [ 1 ] is a, generator of this group, it follows that, Zn . Thus the only subring of Zn, is Zn itself. D, , R., , R, , R, , R=, , Example 5.1.4., , Let be the commutative ring Z6 and let be the subset { [OJ , [2] , [4]} . Then, is closed under addition and multiplication and contains the additive inverse, of each element in Since [4] [0] [0], [4] [2] [2], and [4] [4] [4], the, subset also has an identity element, namely [4] . This shows that can be, considered to be a commutative ring under the operations on but we do not, consider it to be a subring, since its identity element is not the same as the one, D, in, , S, R, , R., , R, , =, , R, , =, , S., , =, R, S,, , Example 5.1.5 (Gaussian integers)., , Let Z[i ] be the set of complex numbers of the form + where, E Z., Since, + + +, + + +, and, +, +, +, +, for all, E Z, the usual sum and product of numbers in Z[i ] have the, correct form to belong to Z[i ] . This shows that Z[i ] is closed under addition, and multiplication of complex numbers. The negative of any element in Z[i], again has the correct form, as does 1 1 + O , so Z[i] is a commutative ring, by Proposition 5 . 1 .4. D, , m, n, r, s, , m ni, m, n, (m ni) (r si) = (m r) (n s)i, (m ni)(r si) = (mr - ns) (nr ms)i ,, ==, , Example 5.1.6 (Z [, , -viz])., , In Example 4. 1 . 1 we verified that Q ,J2, It has an interesting subset, Z[ ,J2] {m +, , i, , ( ) == {a + b,J2 I a, b, == n ,J2 I m, n Z}, , E, , Q} is a field., , E, , which is obviously closed under addition. The product of two elements is, given by, , (m l + n l ,J2)(m 2 + n 2 ,J2) == (m l m 2 + 2n l n 2 ) + (m l n 2 + m 2n l ),J2, , and so the set is also closed under multiplication. Proposition 5. 1 .4 can be, applied to show that Z[ ,J2] is a subring of Q( ,J2), since 1 E Z[ ,J2] ., Since Q ,J2 is a field, it contains, +, whenever +, i= 0,, 2, but, +, E Z[,J2] if and only if, and, 2, are integers. It can be shown that this occurs if and only if, ±1., 2, (See Exercise 4.) D, , ), l/(m( n,J2), , l/(m n,J2)2 2 mn/(mn,J2, m/(m - n ) m 2 - n22 -== n 2 )

Page 8 :

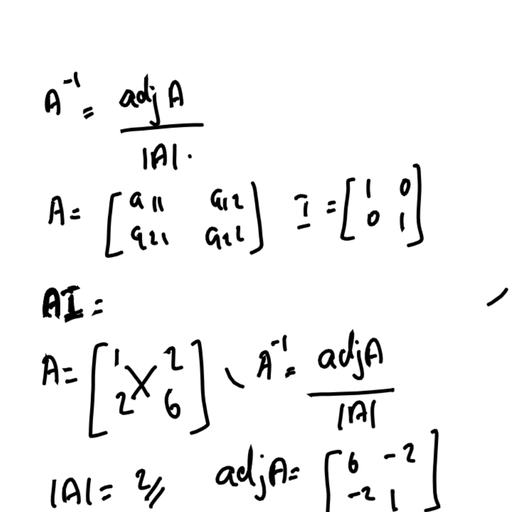

23 1, , 5. 1 . COMMUTATIVE RINGS; INTEGRAL DOMAINS, , Let, R be a commutative ring. An element a E R is said to be, invertible if there exists an element b E R such that ab, 1., In, this, case,, the, element, a, i, s, also, called, a, unit of R , and the element b is called, a multiplicative inverse of a, usually denoted by a - I ., It follows from Proposition 3. 1 .2 that if a E R is invertible, then the multiplica, tive inverse of a is unique. Since 0 b 0 for all b E R, it is impossible for 0 to, be invertible (except in the zero ring). Furthermore, if a E R and ab 0 for some, nonzero b E R, then a cannot be a unit since mUltiplying both sides of the equation, by the inverse of a (if it existed) would show that b, An element a such that ab 0 for some b :F 0 is called a, 5. 1.5 Definition., , ==, , ., , ==, , ==, , ==, , ==, , O., , divisor of zero., , Example 5.1.7., , Let be the set of all functions from the set of real numbers into the set, of real numbers, with ordinary addition and multiplication of functions (not, composition of functions). It is not hard to show that is a commutative ring,, since addition and multiplication are defined pointwise, and the addition and, multiplication of real numbers satisfy all of the field axioms. It is easy to find, divisors of zero in this ring: let f (x) 0 for x < 0 and f (x) 1 for x ::: 0,, and let g (x) 0 for x ::: 0 and g(x) 1 for x < O. Then f(x)g (x) 0 for, all x , which shows that f(x)g (x) is the zero function., The identity element of is the function f (x) 1 (for all x). Then a function, g(x) has a multiplicative inverse if and only if g(x) i= 0 for all x . Thus, for, example, g (x) 2 + sin(x) has a multiplicative inverse, but hex) sin(x), does not. 0, , R, , R, , ====, , ==, , ==, , R, , == ==, , ==, , ==, , When thinking of the units of a commutative ring, here are some good examples, to keep in mind. The only units of are 1 and - 1 . We showed in Proposition 1 .4.5, that the set of units of consists of the congruence classes for which, == 1 ., We showed in Example 3. 1 .4 that is a group under multiplication of congruence, classes., We will use the notation R for the set of units of any commutative ring R ., , Zn, , x, , Z, Z�, , [a ], , (a, n), , Let, R be a commutative ring. Then the set R x of units of R is, an abelian group under the multiplication of R., As usual, let 1 denote the identity of R. If a, b E R X , then a - I and b - I, Proof, exist in R, and so ab E R X since (ab)(b - I a - I ) 1 . We certainly have 1 E R X ,, and a - I E R X since (a - I ) - I a. Finally, the associative and commutative laws, 5.1.6 Proposition., , ==, , hold in R since they hold for all elements of R., , x, , ==, , D

Page 9 :

232, , CHAPTER 5. COMMUTATIVE RINGS, , In the context of commutative rings we can give the following definition. A, field is a commutative ring in which 1 :F 0 and every nonzero element is invertible., We can say, loosely, that a field is a set on which the operations of addition, sub, traction, multiplication, and division can be defined. For example, the real point of, Corollary 1 .4.6 (c) is that is a field if and only if is a prime number., We have already observed that the cancellation law for addition follows from the, existence of additive inverses. A similar result holds for multiplication. If ==, and is a unit, then mUltiplying by, gives, ==, and then by using, I, the associative law for multiplication, the fact that, == 1 , and the fact that, is, an identity element, we see that ==, If the cancellation law for multiplication holds in a commutative ring R, then, for any elements, E R,, == 0 implies that, == 0 or, == O. Conversely, if this, condition holds and ==, then, == 0, so if, :F 0 then, == 0 and, ==, Thus the cancellation law for multiplication holds in R if and only if R has, no nonzero divisors of zero., , Zn, , n, a - I (ab)a - aa - I (ac),, , a- I, b c., a, bab ac,ab a(b - c) a, , a, , b c., , ba, , ab ac, 1, , b-c, , A, commutative, ring, R is called an integral domain if 1 :F 0 and, for all a, b E R,, ab 0 implies a 0 or b 0 ., The ring of integers Z is the most fundamental example of an integral domain., The ring of all polynomials with real coefficients is also an integral domain, since, 5.1.7 Definition., , ==, , ==, , ==, , the product of any two nonzero polynomials is again nonzero. As shown in Exam, ple 5. 1 .7, the ring of all real valued functions is not an integral domain., Our definition of a commutative ring allows the identity element to be equal to, the zero element. Of course, if 1 == 0, then every element of the ring is equal to, zero. In this respect the definition of an integral domain parallels the definition of, a field, as given in Definition 3 .5 .6., , Example 5.1.8, , (D[x], , is an integral domain if, , D, , is an integral domain)., , Let D be any integral domain. The ring D[x] of all polynomials with coeffi, cients in D is also an integral domain. To show this we note that if f (x) and, g(x) are nonzero polynomials with leading coefficients, and, respec, tively, then since D is an integral domain, the product, is nonzero. This, shows that the leading coefficient of the product f (x) g (x) is nonzero, and so, f (x)g(x) i= O. Just as in Proposition 4. 1 .5, we have f (x)g(x) i= 0 because, the degree of f(x)g (x) is equal to deg(f (x)) + deg(g(x)). Since the constant, polynomial 1 is the identity of D [x ] , we certainly have 1 i= O. 0, , a, b, ,, n, m, a m bn, , The next theorem gives a condition that is very useful in studying integral do, mains. It shows immediately, for example, that, are integral domains., and, , Z[i] Z[,J2]

Page 10 :

233, , 5. 1 . COMMUTATIVE RINGS; INTEGRAL DOMAINS, , A converse to Theorem 5 . 1 . 8 will be given in Section 5.4, showing that all integral, domains can essentially be viewed as being subrings of fields. Proving this con, verse involves constructing a field of fractions in much the same way that the field, of rational numbers can be constructed from the integers., , Any subring of afield is an integral domain., Proof, If R is a subring of the field then it inherits the condition 1 i=, If, a,a b 0 orR awithi= 0,aband 0in (intheR),latterthencaseof acourse, the same equation holds in Either, has a multiplicative inverse a- I in even, though the inverse may not be in R . Multiplying both sides of the equation ab 0, (in by a - I gives b 0, and this equation is the same in R as in, Corollary 1 .4.8 (b) shows that Zn is an integral domain if and only if n is a prime, number. It may be useful to go over the proof again. If we use the condition that, abcondition, 0 (mod n) implies that a 0 (mod n) or b 0 (mod n), or equivalently, the, that n I ab implies n I a or n i b, then we can see why n must be prime if, and only if Z is an integral domain. Why should the notions of field and integral, 5.1.8 Theorem., , ==, , F,, , ==, , E, , O., , F., F,, , ==, , F), , F., , =, , =, , D, , ==, , -, , n, domain be the same for the rings Zn ? The next theorem gives an answer, at least, from one point of view., , Any finite integral domain must be afield., Proof, Let be a finite integral domain, and let be the set of nonzero elements, of If d, and d i= 0, then multiplication by d defines a function from into, since ad i= 0 if a i= Let f, be defined by f ( ), d, , for all, Then f is a one-to-one function, since f, f (y) implies xd yd, and, so, y, since the cancellation law holds in an integral domain. But then f must, since by Proposition 2. 1 . 8 any one-to-one function from a finite, onto, map, set into itself must be onto, and so 1 f (a) for some a, That is, ad 1, for some a E D, and so d is invertible. Since we have shown that each nonzero, element of is invertible, it follows that is a field., 5. 1.9 Theorem., , D., *, D ,, x E D* ., x ==, D*, , D*, , D, E D, , :, , O., , D*, , -+, , D*, , (x ), , D* ,, , x, , ==, , ==, , D, , E D* ., , ==, , D*, , x, , ==, , ==, , D, , D, , EXERCISES : SECTION 5.1, , 1 . Which of the following sets are subrings of the field Q of rational numbers? Assume, that m , n are integers with n i- 0 and (m , n) 1 ., t ea) { � I n is odd}, (b) { � I n is even}, t (c) { �, (d) { � I (n ,, I } where is a fixed positive integer, , ==, , 1 4 A' n }, k) ==, , k

Page 11 :

234, , CHAPTER 5. COMMUTATIVE RINGS, , 2. Which of the following sets are subrings of the field R of real numbers?, (a) A { m + n-/2 I m, n E Z and n is even}, (b) B = { m + n-/2 I m, n E Z and m is odd}, (c) C = { a + b� I a, b E Q}, (d) D = { a + b � + c � I a, b, C E Q}, (e) E = { m + nu I m, n E Z} , where u (1 + ,J3)/2, (f) F = { m + nv I m, n E Z} , where v = (1 + 0)/2, 3. Consider the following conditions on the set of all 2 2 matrices [ � ! ] with, =, , =, , x, , rational entries. Which conditions below define a commutative ring? If the set is a, ring, find all units., From your previous work in linear algebra, you may assume that the set of, x matrices over Q satisfies all of the properties of Definition, except the, commutative law for multiplication. Thus it is sufficient to check the commutative, law and the conditions of Proposition, tea) all matrices with d = C 0, (b) all matrices with d, C, t(c) all matrices with d, C, (d) all matrices with d, C, t (e) all matrices with C 0, (f) all matrices with = 0 and d 0, , Hint:, 2 2, , 5.1. 2, , 5.1.4., , a, =, = a, = b, = a, = -2b, = a, = -b, =, a, =, 4. Let R = {m + n-/2 I m, n E Z} ., (a) Show that m + n-/2 is a unit in R if and only if m 2 - 2n 2 = ± 1., Hint:, Show that if (m + n-/2) ( + y -/2) = 1, then (m - n-/2) ( - y -/2) = 1 and, multiply the two equations., (b) Show that 1 + 2-/2 has infinite order in R x ., (c) Show that 1 and -1 are the only units that have finite order in R x ., Let R be a subset of an integral domain D. Prove that if R is a ring under the, 5. operations, of D, then R is a subring of D., 6. Let D be a finite integral domain. Give another proof of Theorem 5.1. 9 by showing, that if is a nonzero element of D, then, = for some positive integer k., 7. An element a of a commutative ring R is called, if a n = 0 for some positive, integer n. Prove that if u is a unit in R and a is nilpotent, then u - a is a unit in R., Hint: First try the case when u = 1., 8. Let R be a commutative ring such that a 2 = a for all a E R. Show that a + a = 0, for all a E R., x, , d, , x, , d- 1, , dk ,, , nilpotent

Page 12 :

235, , 5. 1 . COMMUTATIVE RINGS; INTEGRAL DOMAINS, , 9. Let I be any set and let R be the collection of all subsets of I. Define addition and, multiplication of subsets A , B � I as follows:, A+B, , == (A, , U, , B) n A n B, , A.B, , and, , == A n B ., , Show that R is a commutative ring under this addition and multiplication., 10. For the ring R defined in Exercise 9, write out addition and multiplication tables for, the following cases:, t ea) I has two elements ;, (b) I has three elements., 1 1 . A commutative ring R is called a Boolean ring if, for all E R. Show that, in a Boolean ring the commutative law follows from the other axioms., 12. Let I be any set and let R be the collection of all subsets of I . Define addition and, multiplication of subsets A , B � I as follows:, , a 2 == a, , A+B, , 1 3., , 15., 16., , U, , and, , B, , A.B, , == A n B ., , Is R a commutative ring under this addition and multiplication?, Let R be the set of all continuous functions from the set of real numbers into itself., (a) Show that R is a commutative ring if the formulas +, +, and, for all E R, are used to define addition and multiplication, of functions., (b) Which properties in the definition of a commutative ring fail if the product of two, functions is defined to be, for all x ?, Define new operations on Q by letting EB, + and 0, for all, E Q. Show that Q is a commutative ring under these operations., Define new operations on by letting m EB n m + n - 1 and m 0 n m + n - m n ,, for all m , n E Is a commutative ring under these operations?, Let R and be commutative rings. Prove that the set of all ordered pairs (r, such, that r E R and E can be given a ring structure by defining, , (f . g)(x) == f(x)g (x), , 14., , == A, , a, , a, b, , (f g)(x) == f(x) g (x), , x, , (fg)(x) == f(g (x)),, a b == a b a b == 2ab,, ==, ==, Z. Z Z, S s S, s), , This is called the direct sum of R and denoted by R EB, 17. Give addition and multiplication tables for EB, 1 8. Generalizing to allow the direct sum of three commutative rings, give addition and, multiplication tables for EB EB, 19. Find all units of the following rings., (a) EB, t (b) EB, , S,, , Z2 Z2 Z2·, , Z Z, Z4 Z9, , Z2 Z2 ., , S.

Page 13 :

236, , CHAPTER 5. COMMUTATIVE RINGS, , 20. An element of a ring is said to be idempotent if, elements of the following rings., (a) and, and, (b), (c) EB, EB, (d), , e, Z s Z9, ZIO ZI2, Z Z, Z IO Z I 2, , R, , e2 = e. Find all idempotent, , a E A and n E Z}. Define, R, =, (a,, n), binary, I, {, ., R (a, n) (b, m) = (a + b, n + m) and (a, n) (b, m) =, (a, n) (b, m) in R. Show that R is a commutative ring., , 21 . Let A be an abelian group, and let, operations + and · on by, +, + ,, for all, and, , (am nb nm),, 22. Let R be a set that satisfies all of the axioms of a commutative ring, with the exception, of the existence of a multiplicative identity element. Define binary operations + and, . on R I = { (r, n) I r E R, n E Z } by (r, n) + (s, m) = (r + s, n + m) and, (r, n) . (s, m) = (rs + ns + mr, nm), for all (r, n) and (s, m) in R I . Show that R I, is a commutative ring with identity (0, 1 ) and that { (r, 0) I r E R} satisfies all of the, conditions of a subring, with the exception that it does not have the multiplicative, identity of R., 5.2, , Ring Homomorphisms, , In Chapter 3, we found that homomorphisms played an important role in the study, of groups. Now in studying commutative rings we have two operations to consider., As with groups, we will be interested in functions which preserve the algebraic, properties that we are studying. We begin the section with two examples, each of, which involves an isomorphism., Example 5.2. 1., , The definition of the set of complex numbers usually involves the introduction, of a symbol that satisfies, - 1 , and then we let, , i2 =, = { a + bi I a, b E R} ., In Section 4. 3 we gave another definition by using the field R [x]/ (x 2 + 1 ) , in, which the congruence class [x] plays the role of i. To look for a more concrete, description of we can try to find such an element i with i 2 = - 1 in some, familiar setting. If we identify real numbers with scalar 2 2 matrices over, R, then the matrix, i, , C, , C,, , x, , [ -� � ]

Page 14 :

3 16, , CHAPTER 7. STRUCTURE OF GRO UPS, , then determine how they can be put together to construct groups. The appropriate, building blocks are simple groups, which have no nontrivial normal subgroups. For, any finite group it is possible to find a sequence of subgroups of the type given, above, in which each factor group is simple (but not necessarily simple and abelian,, as is the case for solvable groups)., The problem, then, is to determine the structure of each finite simple group and, to solve the "extension problem." That is, given a group with normal subgroup, such that the structure of as well as that of, are known, what is the structure, of, The extension problem is still open, but the classification of finite simple, groups is generally accepted as complete., An abelian group is simple if and only if it is cyclic of prime order. We will, show in Section 7.7 that the alternating group on elements is simple, if > 5., We can easily describe one other family of finite simple groups. Let be any finite, field, and let == GLn, the group of invertible x matrices over Then, has a normal subgroup == SLn, the subgroup of all matrices of determinant, 1 . (Note that is normal because it is the kernel of the determinant mapping.), The center of which we denote by Z , may be nontrivial, in which case is not, simple. However, the factor group Z is simple except for the cases == 2 and, GF(2) or GF(3) ., William Burnside ( 1 852-1 927) states in the second edition of his text, (published in 1 9 1 1 ) that his research "suggests inevitably, that simple groups of odd order do not exist." He had shown that the order of a, simple finite group of odd order (nonabelian, of course) must have at least seven, prime factors, and then he had checked all orders up to 40 , 000. This was finally, shown to be true in 1 963, by Walter Feit and John Thompson, in a 255-page paper, that proved that all groups of odd order are solvable. This sparked a great deal of, interest in the problem of classifying all finite simple groups, and the classification, was finally completed in 1 98 1 . (The work required the efforts of many people, and, is still being checked and simplified.) There are a number of infinite families of, finite simple groups in addition to those mentioned above. In addition there are, 26 "sporadic" ones, which do not fit into the other classes. The largest of these is, known as the "monster," and has approximately 10 54 elements., , N, , G, G/N, , N, , (F),, N, , n, n n, , n, F F. G, N, n, Theory of, , G?, , G, NN,, , (F),, N/, , F ==, Groups of Finite Order, , 7. 1, , Isomorphism Theorems; Automorphisms, , We need to recall the fundamental homomorphism theorem for groups. If and, are groups, and ¢ :, --*, is a group homomorphism, then ker(¢) is a, normal subgroup of 1 , ¢, is a subgroup of and the factor group, ker (¢), is isomorphic to the image ¢, We will exploit this theorem in proving two, isomorphism theorems. Refer to Figure 7 . 1 . 1 for the first isomorphism theorem and, Figure 7. 1 .2 for the second isomorphism theorem., , G2, , G, G, 1, G (G 1 )(G ).2, 1, , Gi,, , G1/, , G1

Page 15 :

317, Letof G.G Then, be a group,, letsubgroup, N be a, normal, subgroup, of, G,, and, let, H, be, any, subgroup, N, i, s, a, ofG, H n N is a normal subgroup of H, and, (H N) j N H j (H n N) ., Define ¢ : H G j N by ¢ (h) == hN, for all h E H. Since ¢ is the restric, Proof., tion of the natural projection, G G j N, it is a group homomorphism. Recall, that the set N == {hn I h E H, n E N} is a subgroup of G by Proposition, ¢(H) {gN E Gj N I gN hN for some h E H}, {gN E GjN l g E HN}, HNjN, Finally, ker (¢), H, n, N,, and so H n N is a normal subgroup of H. By the, fundamental homomorphism theorem, we have ¢ (H) H j ker(¢) ., Figure 7.1.1:, GI, HN"', /, H", /N, H nI N, {e}, 7. 1 . ISOMORPHISM THEOREMS; AUTOMORPHISMS, , 7. 1.1 Theorem (First Isomorphism Theorem)., , H, , r-v, , --+, , TC :, , --+, , 3 . 3 .2., , H, , ==, , ==, , r-v, , D, , Example 7. 1.1., , Let be the dihedral group Dg , given by elements of order and of order 2,, with, ==, Let N == ( ) , and let ==, Then N is normal, in (see Exercise in Section, N ==, and n N ==, Thus N has two co sets in N, and n N has two, cosets in so it is clear that N / N must be isomorphic to / n N ., , G -l, a 4 8 b, 2, 4, ba a b., a, H { e, a 2, b,4a b}.6 2 4 6, a, GH, 18, 3., 7, ),, H, ,, a, b,, a, b,, a, b},, ,, a, ,, b,, a, {e,, 4, e, }., H H, H, { a, H, HH 0, , Example 7. 1.2., , and let be the set of diagonal matrices, Let ==, let N ==, in Since N is the kernel of the determinant mapping from, into, , G GL2 (Q),, G., , SL2 (Q),, , H, , GL2 (Q) QX,

Page 16 :

CHAPTER 7. STRUCTURE OF GRO UPS, , 318, , it is a normal subgroup of and it is easy to check that H is a subgroup of, Then H n i s the set of diagonal matrices of determinant 1 , and H ==, since any element of (with determinant can be expressed in the form, , N, , G, , G,, , G., N G,, , d), , It follows from the first isomorphism theorem that GL2 (Q) / SL 2 (Q), H/(H n, , N). 0, , Let, G, be, a, group, with, normal, subgroup, of, GIN,, subgroups, N, and, H, such, that, N, H., Then, H, I, N, i, s, a, normal, and, (G I N) I (HI N) G I H ., Proof., By HI N we mean the set of all co sets of the form hN, where h E H. Define, aH for all a E G. Then ¢ is well-defined since if, ¢aN: GINbN forGaI, Hb EbyG,¢ (aN), we have b - 1 a E N . Since N H, this implies b- 1 a E H,, and so aH bH. It is clear that ¢ maps GI N onto GI To show that ¢ is a, homomorphism we only need to note that, ¢(aNbN) ¢(abN) abH aHbH ¢(aN)¢(bN) ., Finally, ker(¢), {aN, I, aH, H}, HIN,, and so HIN is a normal sub, group of GIN. The fundamental homomorphism theorem for groups implies that, (GIN) I ker(¢) GIH, the desired result., 7. 1.2 Theorem (Second Isomorphism Theorem)., C, r-v, , ==, , ---*, , ==, , C, , H., , ==, , ==, , ==, , ==, , ==, , ==, , ==, , ==, , D, , r-v, , Figure 7 . 1 . 2 :, , GIN ¢, � GIH, (GIN) I� (HIN), �, , Example 7.1.3, , (Zn lmZn, , r-v, , Z m if, , mi n )., , We have already proved this directly, in Example 3.8. 10, but it also follows, immediately from the second isomorphism theorem. Let == let, be, positive integers with, let ==, and let H ==, Then C H, and, so by the second isomorphism theorem we have / / (H /, / H., , mi n , N nZ,, , G Z,N m, n, mZ., (G N) N) G, r-.J

Page 17 :

319, , 7. 1 . ISOMORPHISM THEOREMS; AUTOMORPHISMS, , That is,, �, In our standard notation, this is written, as, �, Of course, since is cyclic, every subgroup of has, the form, for some positive divisor of and so we have characterized, all factor groups of . D, , (ZI, nZ), 1, (mZI, nZ), ZI, mZ., Zn 1 mZn Zm ., Zn, mZn ,, m n,, Zn, , Zn, , Example 7. 1.4., , Let == Dg , and let N and be the subgroups defined in Example 7. 1 . 1 ., Then N and n N are normal in and n N e N. It follows from the, D, second isomorphism theorem that, n N)), n N)) �, , G, , H G, H, (G/(H 1 (N I(H, , H, , GIN., , The next theorem will be crucial in proving later theorems which describe the, structure of a finite abelian group. It is also useful in proving, for example, that, D6 � S3 X since we would only need to find normal subgroups of D6 isomorphic, to S3 and which satisfy the conditions of the theorem., , ZZ 2 ,, 2, Let, G, be, a, group, with, normal, subgroups, H, K such that H K == G, and H K == {e}. Then G � H K., Proof, We claim that ¢ : H K, G, defined by ¢(h, k) == hk, for all (h, k) E, H K is a homomorphism. First, for all (h I , k I ), (h 2 , k2 ) E H K we have, 7. 1.3 Theorem., n, x, , x, , x, , ---+, , x, , To show that this is equal to, it suffices to show that, For any elements, H and, K , we have, K and, H. By assumption, H n K since, or, We have now verified our claim, HnK, and so, that ¢ is a homomorphism., Since H K, it is clear that ¢ is onto. Finally, if ¢, for, H x K , then, implies, H n K , and so == and, which, shows that ker(¢) is trivial and hence ¢ is one-to-one. D, , h 2khkh, I == -kII h, 2k. - I E h, kh -hI kE- I E k E, hkh - I k - I == e, hk == kh., ==, G,, ((h,, k)), ==, e, (h,, k), E, l, hk == e h == k - E, h e k == e,, We have been using the definition that a subgroup H of a group G is normal if, ghg - l E H for all h E H and g E G. We now introduce a more sophisticated point, E, hkh - I k -==I {e},, , of view using the notion of an inner automorphism. The more general notion of an, automorphism of a group is also extremely important., , Let -GI forbe alla group, a E G. The function ia G G, defined by ia(x) == axa, x E Gandis anletisomorphism., , 7.1.4 Proposition., , ---+

Page 18 :

CHAPTER 7. STR UCTURE OF GROUPS, , 320, , Proof If x, y E G, then, ia (xy) a(xy)a - I == (axa - I ) (aya- I ) ia (x )ia (y) ,, and so ia is a homomorphism. If ia (x) e, then ax a - I == e, so x == e and ia is, one-to-one since its kernel is trivial. Given y E G, we have y ia(a - 1 ya), and so, ia is also an onto mapping., Let G be a group. An isomorphism from G onto G is called an, automorphism of G., An, automorphism, of, G of the form ia, for some a E G, where ia(x) == axa- I, for all x E G, is called an inner automorphism of G., The, set, of, all, automorphisms, of, G will be denoted by Aut( G) and the set of all, inner automorphisms of G will be denoted by Inn( G)., The condition that a subgroup H of G is normal can be expressed by saying that, ia(h), E H for all h E H and all a E G. Equivalently, H is normal if and only if, ia (H) H for all a E G, and we can also express this by saying that H is invariant, ==, , ==, , ==, , ==, , D, , 7.1.5 Definition., , C, , under all inner automorphisms of G., , Let, G be a group. Then Aut(G) is a group under composition, offunctions, and Inn (G) is a normal subgroup of Aut(G)., Proof, Composition of functions is always associative. We already know that the, composite of two isomorphisms is again an isomorphism, and that the inverse of an, isomorphism is an isomorphism, so it follows immediately that Aut(G) is a group., For any elements a, b E G , we have, 7.1.6 Proposition., , for all E G, and so this yields the formula, It follows easily that, is the identity mapping and, ==, so Inn (G) is a subgroup of Aut(G) . To, show that it is normal, let E Aut(G) and let E Inn(G) . For E G, we have, , x, , iai, ie, ==, iab., b, I, (ia), i, ,, a, l, fJ, ia, x, fJ(a(fJ - 1 (x))aI - l ) 1, (fJ (a) ) (fJfJ - (x) ) (fJI (a - ) ) I, (fJ (a) ) (x) (fJ (a) ) - bx b ibeX), for the element b == fJ(a). Thus fJiafJ- 1 E Inn(G), and so Inn(G) is a normal, subgroup of Aut(G) ., ==, , D

Page 19 :

32 1, , 7. 1 . ISOMORPHISM THEOREMS; AUTOMORPHISMS, , For any group G, the subset, Z(G) == { x E G I xg == gx for all g E G }, is called the center of G., For any group G, the center Z(G) is a normal subgroup, and, , 7.1 .7 Definition., , 7.1.8 Proposition., , GjZ (G) � Inn (G) ., , a == ia, for all a E G. Then, ¢ ( ab ) == iab == iaib == ¢ (a )¢ (b ), and we have defined a homomorphism. Since ¢ is onto by the definition of lnn(G) ,, we only need to compute ker(¢). If ia is the identity mapping, then for all x E G, we have axa - l == x, or ax == xa, so the kernel of ¢ is the center Z (G) . It follows, , Proof, , Define ¢ : G, , ---+, , Inn(G) by ¢ ( ), , that Z(G) is normal, and that GjZ (G) � Inn(G) ., Example 7. 1.5, , (Aut(Z) � Z2 and Inn(Z), , D, , == { I })., , To compute Aut(Z) and Inn(Z) we first observe that all inner automorphisms, of an abelian group are trivial (equal to the identity mapping). Next, we, observe that any isomorphism between cyclic groups maps generators to gen, erators, so if a Aut(Z) , then a ( l ) == ± 1 . Thus there are two possible, automorphisms, with the formulas a (n) == n or a(n) == -n, for all n Z. D, , E, , Example 7.1.6, , E, , (Aut (Zn ) � Z� )., , The computation of Aut(Zn ) is similar to that of Aut(Z) . For any automor, phism a of Zn , let a([I]) == [a] . Since [ 1 ] is a generator, [a] must also be, a generator, and thus gcd(a , n) == 1 . Then a must be given by the formula, a([m]) == [am], for all [m] Zn . Since the composition of such functions, corresponds to multiplying the coefficients, it follows that Aut(Zn ) � Z� ,, where Z� is the multiplicative group of units of Zn . D, , E, , EXERCISES: SECTION 7.1, , 1 . In, , H, , Z;2 find cyclic subgroups of order 2 and K of order 8 with, n K ==, Conclude that Z;2 � Z2 x Zg ., , G, , ==, , {e } ., , H, , H K G and, ==

Page 20 :

CHAPTER 7. STRUCTURE OF GRO UPS, , 322, , 2. Prove that D6 � S3 x Z2 ., 3.t Determine Aut(Z2 x Z2 )., 4. Let G be a finite abelian group of order and let be a positive integer with, G belongs to, == 1 . Show that : G � G defined by, for all, ==, Aut(G)., G. Find, 5.tLet : G � G be the function defined by, for all, ==, conditions on G such that is an automorphism., 6. Show that for G == S3 , Inn(G) � G., 7.t Determine Aut(S3 )., 8. For groups GI and G 2 , determine the center of GI x G 2 ., 9. Show that G / Z (G) cannot be a nontrivial cyclic group. (That is, if G / Z (G) is cyclic,, then G must be abelian, and hence Z (G) == G .), 10. Describe the centers Z (Dn ) of the dihedral groups Dn , for all integers 2: 3., 1 1 . In the group GL2 (C) of all invertible 2 x 2 matrices with complex entries, let Q be, the following set of matrices (the quatemion group, defined in Example 3.3.7):, , (n, m), ¢, , n,, , ¢, , ¢, , mm, ¢(g) g, gE, ¢(g) g - l g E, , n, , (a) Show that Q is not isomorphic to D4 ., (b) Find the center Z ( Q) of Q., , [� l, , 7, 1 2. Let F20 be the subgroup of GL 2 (Zs) consisting of all matrices of the form, such that, Z5 and i=- 0, as defined in Exercise 23 of Section 3.8. This group, will be called the Frobenius group of degree 5. Find the center of F20., 13. Show that the Frobenius group F20 defined in Exercise 1 2 can be defined by generators, and relations as follows. Let =, and =, , m, n E, , m, , a, , [� �], , b, , [ � � J., , (a) Show that ( ) == 5,, == 4, and, == 2 ., (b) Show that each element of F20 can be expressed in the form, and 0 :::; j :::; 3 ., , oa, , o(b), , ba a b, , a i bj for 0 :::; i :::; 4, a, 14. Let G be the subgroup of GL2 (R) consisting of all matrices [ a ll aa l 2 ] such that, a21 0 and a22 1 . (See Exercises 10 and 1 1 of Section 3. 1 .) 21 22, (a) Let N be the set of matrices in G with a l l 1 . Show that N is a normal subgroup, of G ., (b) Let a [ � � ] and b [ � � l Show that if H ( a ) , then bHb - i i s a, proper subset of H. Conclude that H is not normal in any subgroup that contains b., ==, , ==, , =, , ==, , =, , =