Page 1 :

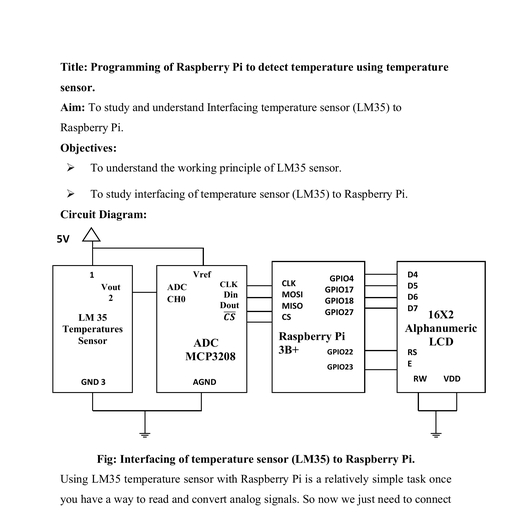

INTRODUCTION TO, EMBEDDED SYSTEMS, Second Edition

Page 2 :

About the Author, , Shibu Kizhakke Vallathai has over fifteen years of hands-on experience in the Embedded & Real Time, System domain with solid background on all phases of Embedded Product Development Life Cycle. He, holds a B Tech Degree (Hons) in Instrumentation & Control Engineering from the University of Calicut,, Kerala. He started his professional career as Research Associate in the VLSI and Embedded Systems Group, of India’s prime Electronics Research & Development Centre (ER&DCI—under the ministry of Information, & Communication Technology, Government of India) Thiruvananthapuram Unit. He has conducted research, activities in the embedded domain for Contactless Smart Card Technology and Radio Frequency Identification, (RFID). He has developed a variety of products in the Contactless Smart Card & RFID Technology platform, using industry’s most popular 8-bit microcontroller—8051., Shibu has sound working knowledge in Embedded Hardware development using EDA Tools and, firmware development in Assembly Language and Embedded C using a variety of IDEs and cross-compilers, for various 8/16/32 bit microprocessors/microcontrollers and System on Chips. He is also an expert in, RTOS based Embedded System design for various RTOSs including Windows CE, VxWorks, MicroC/, OS-II and RTX-51. He is well versed in various industry standard protocols and bus interfaces. Presently,, he is engaged with the Devices Group of Microsoft Corporation, USA (www.microsoft.com) as senior, Firmware Engineer. Prior to joining Microsoft, he was engaged with the Embedded Systems and Product, Engineering practice unit of Infosys Technologies Limited (www.infosys.com), Thiruvananthapuram unit as, senior Technology Architect.

Page 3 :

INTRODUCTION TO, EMBEDDED SYSTEMS, Second Edition, , Shibu Kizhakke Vallathai, Senior Firmware Engineer, Microsoft Corporation, , McGraw Hill Education (India) Private Limited, NEW DELHI, McGraw Hill Education Offices, New Delhi New York St Louis San Francisco Auckland Bogotá Caracas, Kuala Lumpur Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan Montreal, San Juan Santiago Singapore Sydney Tokyo Toronto

Page 4 :

McGraw Hill Education (India) Private Limited, Published by McGraw Hill Education (India) Private Limited,, P-24, Green Park Extension, New Delhi 110 016., Introduction to Embedded Systems, 2e, Copyright © 2017, 2009 by McGraw Hill Education (India) Private Limited, No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,, photocopying, recording, or otherwise or stored in a database or retrieval system without the prior written permission of, the publishers. The program listing (if any) may be entered, stored and executed in a computer system, but they may not, be reproduced for publication., This edition can be exported from India only by the publishers,, McGraw Hill Education (India) Private Limited., Print Edition:, ISBN (13): 978-93-392-1968-0, ISBN (10): 93-392-1968-6, E-Book Edition:, ISBN (13): 978-93-392-1969-7, ISBN (10): 93-392-1969-4, Managing Director: Kaushik Bellani, Director—Products (Higher Education and Professional): Vibha Mahajan, Specialist—Product Development: Piyush Priyadarshi, Researcher—Product Development: Lubna Irfan, Head—Production (Higher Education and Professional): Satinder S Baveja, Senior Copy Editor: Kritika Lakhera, Senior Production Specialist: Suhaib Ali, Assistant General Manager—Product Management (Higher Education and Professional): Shalini Jha, Manager—Product Management: Kartik Arora, General Manager—Production: Rajender P Ghansela, Manager—Production: Reji Kumar, Information contained in this work has been obtained by McGraw Hill Education (India), from sources believed to be, reliable. However, neither McGraw Hill Education (India) nor its authors guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any, information published herein, and neither McGraw Hill Education (India) nor its authors shall be responsible for any errors,, omissions, or damages arising out of use of this information. This work is published with the understanding that McGraw, Hill Education (India) and its authors are supplying information but are not attempting to render engineering or other, professional services. If such services are required, the assistance of an appropriate professional should be sought., , Typeset at Text-o-Graphics, B-1/56, Aravali Apartment, Sector-34, Noida 201 301, and printed at, Cover Printer:, , Visit us at: www.mheducation.co.in

Page 5 :

I dedicate this book to all Infoscions, my beloved mother late Smt. Santha, my wife Cini,, my son Tejas, my papa, my friends, my other family members and my loved ones

Page 7 :

Contents, , Preface, Acknowledgements, , xiii, xvii, , Part-1: Embedded Systems: Understanding the Basic Concepts, , 1, , 1., , 3, , Introduc on to Embedded Systems, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, 1.6, 1.7, , 2., , What is an Embedded System? 4, Embedded Systems VS. General Computing Systems 4, History of Embedded Systems 5, Classification of Embedded Systems 6, Major Application Areas of Embedded Systems 8, Purpose of Embedded Systems 8, Wearable Devices—The Innovative Bonding of Lifestyle with Embedded Technologies 11, Summary 13, Keywords 14, Objective Questions 14, Review Questions 15, , The Typical Embedded System, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4, 2.5, 2.6, 2.7, , Core of the Embedded System 18, Memory 29, Sensors and Actuators 35, Communication Interface 45, Embedded Firmware 59, Other System Components 60, PCB and Passive Components 64, Summary 64, Keywords 65, Objective Questions 67, Review Questions 70, Lab Assignments 72, , 16

Page 8 :

viii, , 3., , Contents, , Characteris cs and Quality A ributes of Embedded Systems, 3.1, 3.2, , 4., , Embedded Systems—Applica on- and Domain-Specific, 4.1, 4.2, , 5., , 6., , 7., , Different Addressing Modes Supported by 8051, The 8051 Instruction Set 175, Summary 199, Keywords 200, Objective Questions 201, Review Questions 206, Lab Assignments 207, , 168, 169, , Hardware So ware Co-Design and Program Modelling, 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, , 93, , Factors to be Considered in Selecting a Controller 94, Why 8051 Microcontroller 95, Designing with 8051 96, The 8052 Microcontroller 157, 8051/52 Variants 157, Summary 158, Keywords 159, Objective Questions 160, Review Questions 164, Lab Assignments 166, , Programming the 8051 Microcontroller, 6.1, 6.2, , 84, , Washing Machine—Application-Specific Embedded System 84, Automotive–Domain Specific Examples of Embedded System 86, Summary 90, Keywords 91, Objective Questions 91, Review Questions 92, , Designing Embedded Systems with 8bit Microcontrollers—8051, 5.1, 5.2, 5.3, 5.4, 5.5, , 73, , Characteristics of an Embedded System 73, Quality Attributes of Embedded Systems 75, Summary 80, Keywords 80, Objective Questions 81, Review Questions 82, , Fundamental Issues in Hardware Software Co-Design 210, Computational Models in Embedded Design 212, Introduction to Unified Modelling Language (UML) 220, Hardware Software Trade-offs 225, Summary 225, Keywords 226, Objective Questions 228, Review Questions 229, Lab Assignments 230, , 209

Page 9 :

Contents, , Part-2: Design and Development of Embedded Product, 8., , Embedded Hardware Design and Development, 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4, 8.5, 8.6, 8.7, 8.8, , 9., , 234, , 308, , Embedded Firmware Design Approaches 309, Embedded Firmware Development Languages 312, Programming in Embedded C 324, Summary 376, Keywords 377, Objective Questions 378, Review Questions 383, Lab Assignments 386, , 10. Real-Time Opera ng System (RTOS) based Embedded System Design, 10.1, 10.2, 10.3, 10.4, 10.5, 10.6, 10.7, 10.8, 10.9, 10.10, , 231, , Analog Electronic Components 235, Digital Electronic Components 236, VLSI and Integrated Circuit Design 249, Electronic Design Automation (EDA) Tools 254, How to use the OrCAD EDA Tool? 255, Schematic Design using Orcad Capture CIS 255, The PCB Layout Design 273, Printed Circuit Board (PCB) Fabrication 293, Summary 299, Keywords 300, Objective Questions 301, Review Questions 304, Lab Assignments 305, , Embedded Firmware Design and Development, 9.1, 9.2, 9.3, , ix, , 387, , Operating System Basics 389, Types of Operating Systems 392, Tasks, Process and Threads 396, Multiprocessing and Multitasking 408, Task Scheduling 410, Threads, Processes and Scheduling: Putting them Altogether 428, Task Communication 433, Task Synchronisation 449, Device Drivers 482, How to Choose an RTOS 484, Summary 485, Keywords 487, Objective Questions 489, Review Questions 499, Lab Assignments 504, , 11. An Introduc on to Embedded System Design with VxWorks and MicroC/OS-II RTOS, 11.1 VxWorks 508, 11.2 MicroC/OS-II 523, , 507

Page 10 :

x, , Contents, , Summary 552, Keywords 553, Objective Questions 554, Review Questions 556, Lab Assignments 557, , 12. Integra on and Tes ng of Embedded Hardware and Firmware, , 560, , 12.1 Integration of Hardware and Firmware 561, 12.2 Board Bring up 565, Summary 566, Keywords 567, Review Questions 567, , 13. The Embedded System Development Environment, 13.1, 13.2, 13.3, 13.4, 13.5, 13.6, , 568, , The Integrated Development Environment (IDE) 570, Types of Files Generated on Cross-Compilation 598, Disassembler/Decompiler 607, Simulators, Emulators and Debugging 607, Target Hardware Debugging 615, Boundary Scan 617, Summary 619, Keywords 620, Objective Questions 621, Review Questions 622, Lab Assignments 623, , 14. Product Enclosure Design and Development, , 624, , 14.1 Product Enclosure Design Tools 625, 14.2 Product Enclosure Development Techniques 625, 14.3 Summary 627, Summary 628, Keywords 629, Objective Questions 629, Review Questions 630, , 15. The Embedded Product Development Life Cycle (EDLC), 15.1, 15.2, 15.3, 15.4, 15.5, , What is EDLC? 632, Why EDLC 632, Objectives of EDLC 633, Different Phases of EDLC 635, EDLC Approaches (Modeling the EDLC) 646, Summary 651, Keywords 652, Objective Questions 653, Review Questions 654, , 631

Page 11 :

Contents, , 16. Trends in the Embedded Industry, 16.1, 16.2, 16.3, 16.4, 16.5, 16.6, 16.7, , xi, , 656, , Processor Trends in Embedded System 657, Embedded OS Trends 659, Development Language Trends—BEYOND EMBEDDED C 660, Open Standards, Frameworks and Alliances 663, Bottlenecks 664, Development Platform Trends 665, Cloud, Internet of Things (IoT) and Embedded Systems – The Next Big Thing 666, , Appendix I: Overview of PIC and AVR Family of Microcontrollers and ARM Processors, Appendix II: Design Case Studies, Bibliography, Index, , 669, 688, 726, 728

Page 13 :

Preface, , There exists a common misconception amongst students and young practising engineers that embedded, system design is ‘writing ‘C’ code’. This belief is absolutely wrong and I strongly emphasise that embedded, system design refers to the design of embedded hardware, embedded firmware in ‘C’ or other supporting, languages, integrating the hardware and firmware, and testing the functionalities of both., Embedded system design is a highly specialised branch of Electronics Engineering where the technological, advances of electronics and the design expertise of mechanical engineering work hand-in-hand to deliver, cutting edge technologies and high-end products to a variety of diverse domains including consumer, electronics, telecommunications, automobile, retail and banking applications. Embedded systems represent, an integration of computer hardware, software along with programming concepts for developing specialpurpose computer systems, designed to perform one or a few dedicated functions., The embedded domain offers tremendous job opportunities worldwide. Design of embedded system is, an art, and it demands talented people to take up the design challenges keeping the time frames in mind., The biggest challenge faced by the embedded industry today is the lack of skilled manpower in the domain., Though most of our fresh electronics and computer science engineering graduates are highly talented, they, lack proper training and knowledge in the embedded domain. Lack of suitable books on the subject is one of, the major reasons for this crisis. Although various books on embedded technology are available, almost none, of them are capable of delivering the basic lessons in a simple and structured way. They are written from a, high-end perspective, which are appropriate only for the practising engineers., This book ‘Introduction to Embedded Systems’ is the first-of-its-kind, which will appeal as a, comprehensive introduction to students, and as a guide to practising engineers and project managers. It, has been specially designed for undergraduate courses in Computer Science & Engineering, Information, Technology, Electrical Engineering, Electronics & Communication Engineering and Instrumentation, & Control Engineering. Also, it will be a valuable reference for the students of BSc / MSc / MTech, (CS/IT/Electronics), MCA and DOEACC ‘B’ level courses., The book has been organised in such a way to provide the fundamentals of embedded systems;, the steps involved in the design and development of embedded hardware and firmware, and their integration;, and the life cycle management of embedded system development. Chapters 1 to 4 have been structured, to give the readers a basic idea of an embedded system. Chapters 5 to 13 have been organised to give an, in-depth knowledge on designing the embedded hardware and firmware. They would be very helpful to, practising embedded system engineers. Chapter 15 dealing with the design life cycle of an embedded system, would be beneficial to both practising engineers as well as project managers. Each chapter begins with, learning objectives, presenting the concepts in simple language supplemented with ample tables, figures, and solved examples. An important part of this book comes at the end of each chapter where you will find a

Page 14 :

xiv, , Preface, , brief summary, list of keywords, objective questions (in multiple-choice format) and review questions. To, aid students commence experimentation in the laboratory, lab assignments have been provided in relevant, chapters. An extremely beneficial segment at the end of the book is the overview of PIC & AVR Family, of Microcontrollers & ARM Processors as well as innovative design case studies presenting real-world, situations., The major highlights of this book are as follows:, �, Brings an entirely different approach in the learning of embedded system. It looks at embedded, systems as a whole, specifies what it is, what it comprises of, what is to be done with it and how to, go about the whole process of designing an embedded system., �, Follows a design- and development-oriented approach through detailed explanations for Keil, Micro Vision (i.e., embedded system/integrated development environment), ORCAD (PCB design, software tool) and PCB Fabrication techniques., �, Practical implementation such as washing machines, automotives, and stepper motor and other I/O, device interfacing circuits., �, Programming concepts: deals in embedded C, delving into basics to unravelling advance level, concepts., �, Complete coverage of the 8051 microcontroller architecture and assembly language programming., �, Detailed coverage of RTOS internals, multitasking, task management, task scheduling, task, communication and synchronisation. Ample examples on the various task scheduling policies., �, Comprehensive coverage on the internals of MicroC/OS-II and VxWorks RTOS kernels., �, Written in lucid, easy-to-understand language with strong emphasis on examples, tables and, figures., �, Useful reference for practicing engineers not well conversant with embedded systems and their, applications., �, Rich Pedagogy includes objective questions, lab assignments, solved examples and review, questions., The comprehensive online learning centre http://www.mhhe.com/shibu/es2e accompanying this book, offers valuable resources for students, instructors and professionals., For Instructors, �, PowerPoint slides (chapter-wise), �, A brief chapter on Embedded Programming Language C++/ Java, �, Case studies given in the book, �, Solution manual (chapter-wise), �, Short questions, quizzes in the category of fill in the blanks, true/false and multiple choice questions, (25); programming questions with solution (5). (Level of difficulty: hard), �, Chapter-wise links to important websites and important text materials, �, Digital Pedometer, �, Micro/OSIII, �, Designing with TI MSP430 RISC Microcontrollers, For Students, �, Chapter-wise tutorials, �, A brief chapter on Embedded Programming Language C++/ Java, �, Case studies given in the book and, �, Answers for objective questions/selected review questions and hints for lab assignments provided in, the book., �, Digital Pedometer

Page 15 : Preface, , xv, , Additional detailed reading material on Micro C/OS III, Designing with TI MSP430 RISC Microcontrollers, �, Short questions, self-test quizzes in the category of fill in the blanks, true/false and multiple choice, questions (25); programming questions with solutions (5). (Level of difficulty: easy/medium/, difficult), �, List of project ideas, �, Chapter-wise links to important websites and important text materials., This book is written purely on the basis of my working knowledge in the field of embedded hardware, and firmware design, and expertise in dealing with the life cycle management of embedded systems. A few, descriptions and images used in this book are taken from websites with prior written copyright permissions, from the owner of the site/author of the articles., The design references and data sheets of devices including the parametric reference used in the illustrative, part of this book are taken from the following websites. Readers are requested to visit these sites for getting, updates and more information on design articles. Also, you can order some free samples from some of the, sites for your design., �, �, , www.intel.com, www.maxim-ic.com, www.atmel.com, www.analog.com, www.microchip.com, www.ti.com, www.nxp.com, www.national.com, www.fairchildsemi.com, www.intersil.com, www.freescale.com, www.xilinx.com, www.orcad.com, www.keil.com, www.embedded.com, www.electronicdesign.com, , Intel Corporation, Maxim/Dallas Semiconductor, Atmel Corporation, Analog Devices, Microchip Technology, Texas Instruments, NXP Semiconductors, National Semiconductor, Fairchild Semiconductor, Intersil Corporation, Freescale Semiconductor, Xilinx (Programmable Devices), Cadence Systems (Orcad Tool), Keil (MicroVision IDE), Online Embedded Magazine, Electronic Design Magazine, , I would be looking forward to suggestions for further improvement of the book which can be sent to,

[email protected]. Kindly mention the title and author name in the subject line. Wish you luck as, you embark on an exhilarating career path!, , Shibu Kizhakke Vellathai

Page 17 :

Acknowledgements, , I take this opportunity to thank Mohammed Rijas (CEO Attinad Software and former Group Project, Manager, Mobility and Embedded Systems Practice, Infosys Technologies Ltd Thiruvananthapuram) and, Shafeer Badharudeen (CTO Attinad Software and former Senior Project Manager, Mobility and Embedded, Systems Practice, Infosys Technologies Ltd Thiruvananthapuram) for their valuable suggestions and, guidance in writing this book. I am also grateful to my team and all other members of the Embedded Systems, Group, Infosys Technologies for inspiring me to write this book. I acknowledge my senior management, team at the Embedded Systems and Mobility practice, Infosys Technologies—Rohit P, Srinivasa Rao, M, Tadimeti Srinivasan, Darshan Shankavaram and Ramesh Adiga—for their constant encouragement, and appreciation of my efforts. I am immensely grateful to R Ravindra Kumar (Senior Director, CDAC, Thiruvananthapuram) for giving me an opportunity to work with the Hardware Design Group of CDAC, (Erstwhile ER&DCI), K G Sulochana (Joint Director CDAC Thiruvananthapuram) for giving me the first, embedded project to kick start my professional career and also for all the support provided to me during my, tenure with CDAC. I convey my appreciation to Biju C Oommen (Associate Director, Hardware Design, Group, CDAC Thiruvananthapuram), who is my great source of inspiration, for giving me the basic lessons, of embedded technology, S Krishnakumar Rao, Sanju Gopal, Deepa R S, Shaji N M and Suresh R Pillai for, their helping hand during my research activities at CDAC, and Praveen V L whose contribution in designing, the graphics of this book is noteworthy. I extend my heartfelt gratitude to all my friends and ex-colleagues of, Hardware Design Group CDAC Thiruvananthapuram—without their prayers and support, this book would, not have been a reality. Last but not the least, I acknowledge my beloved friends and my family members for, their understanding and support during the writing of this book., A token of special appreciation to S Krishnakumar Rao (Joint Director, Hardware Design Group, CDAC, Thiruvananthapuram) for helping me in compiling the section on VLSI Design and Shameerudheen P T for, his help in compiling the section on PCB Layout Design using Orcad Layout Tool., I would like to extend my special thanks to the following persons for coordinating and providing, timely feedback on all requests to the concerned product development/service companies, semiconductor, manufacturers and informative web pages., Angela Williams of Keil Software, Natasha Wan, Jessen Wehrwein and Scott Wayne of Analog Devices, Derek Chan of Atmel Asia, Moe Rubenzahl of Maxim Dallas Semiconductor

Page 20 :

Visual Walkthrough, , LEARNING OBJECTIVES, LEARNING OBJECTIVES, LO 1, LO 2, LO 3, LO 4, , Know what an embedded system is, Differen ate between embedded and general compu ng systems, Underline the history of embedded systems, Classify embedded systems based on performance, complexity and the era in which, they evolved, LO 5 Explain the domains and areas of applica ons of embedded systems, LO 6 Iden fy the different purposes of embedded systems, LO 7 Analyse a real life example on the bonding of embedded technology with human, life, , Our day-to-day life is becoming more and more dependent on “embedded systems” and digital technologies., Embedded technologies are bonding into our daily activities even without our knowledge. Do you know the, f, h h, fi, hi, hi, i, i, di i, l ii, DVD l, d, , Learning Objectives appear at the, beginning of every chapters are intended, to provide students the opportunity to, prepare for what they will be required to, understand in their reading and learning, of the chapter., , LEARNING OBJECTIVES TAGGING, 1.1, , WHAT IS AN EMBEDDED SYSTEM?, , An embedded system is an electronic/electro-mechanical system designed to, perform a specific function and is a combination of both hardware and firmware, (software)., Every embedded system is unique, and the hardware as well as the firmware is, highly specialised to the application domain. Embedded systems are becoming an, inevitable part of any product or equipment in all fields including household appliances, telecommunications,, medical equipment, industrial control, consumer products, etc., LO 1 Know what, an embedded, system is, , 1.2, , It is indicated in every chapter where, specific learning objectives are covered, inside a chapter and also help learners, identify how sections are keyed to the, objectives., , EMBEDDED SYSTEMS VS. GENERAL COMPUTING SYSTEMS, , The computing revolution began with the general purpose computing, requirements. Later it was realised that the general computing requirements are not, sufficient for the embedded computing requirements. The embedded computing, requirements demand ‘something special’ in terms of response to stimuli, meeting, the computational deadlines, power efficiency, limited memory availability, etc., Let’s take the case of your personal computer, which may be either a desktop PC, or a laptop PC or a tablet PC. It is built around a general purpose processor like an Intel® Celeron/Core M or, *, a Duo/Quad core or an AMD A-Series processor and is designed to support a set of multiple peripherals like, l i l USB 3 0, Wi Fi h, id, IEEE1394 SD/CF/MMC, li, f, Bl, h, LO 2 Differentiate, between embedded, and general, computing systems

Page 21 :

xxi, , Visual Walkthrough, , SECTIONS AND SUB-SECTIONS, 6.1 DIFFERENT ADDRESSING MODES SUPPORTED BY 8051, The term ‘addressing mode’ refers to “How the operand is specified in an, instruction” along with opcode. The operand may be one or a combination, of the following–memory location(s), contents of memory location(s),, register(s), or constant. Depending on the type of operands, the addressing, modes are classified as follows., , LO 1 Learn how to, program the 8051, microcontroller using, Assembly Language, , 6.1.1 Direct Addressing, The operand is specified as an 8 bit memory address. For 8051 processor, only the lower 128 byte internal, data memory and the SFRs are directly accessible., For example, MOV A, 07H (Moves the content of memory location 07H to the accumulator. 07H refers, to the address of data memory at location 7. If memory location 07H contains the value 255, executing this, instruction will modify the content of A to 255) uses MOV as opcode and A, 07H as operands (Fig. 6.1)., Registers, , A, , Each chapter has been neatly divided, into Sections and Sub-sections so that, the subject matter is studied in a logical, progression of ideas and concepts., , Data memory, , Memory, address, , SOLVED EXAMPLES, Provided at appropriate locations, Solved, Examples aid in understanding of the, fundamentals of embedded hardware, and firmware design., , Example 2, Register R0 contains 0BH. Add the contents of register R0 with the sum obtained in the previous example, using ADDC instruction. Explain the output of the summation and the status of the carry flag after the, addition operation., The instruction ADDC A, R0 adds accumulator content with contents of register R0 and the carry flag, (CY). Before executing this instruction, the accumulator contains the sum of previous addition operation,, which is 0FH and the carry flag (CY) is in the set state. Register R0 contains 0BH. Executing the instruction, ADDC A, R0 adds 0FH with 0BH and 1. The resulting output is 1BH which is less than FFH. This resets the, carry flag. Accumulator register holds the sum. It should be noted that each addition operation sets or resets, the carry flag based on the result of addition, regardless of the previous condition of the carry flag. Figure, 6.12 explains the ADDC operation., D7 D6 D5 D4 D3 D2 D1 D0, A, ADDC A,R0, , 0, , 0, , 0, , 0, , 1, , 1, , 1, , R0, , 1, , 0FH, , CY, =1, , +, 0, , 0, , 0, , 0, , 1, , 0, , 1, , 1, , 0BH, , 1.6.3 Data (Signal) Processing, As mentioned earlier, the data (voice, image, video,, electrical signals, and other measurable quantities), collected by embedded systems may be used for, various kinds of data processing. Embedded systems, with signal processing functionalities are employed in, applications demanding signal processing like speech, coding, synthesis, audio video codec, transmission, applications, etc., A digital hearing aid is a typical example of an, embedded system employing data processing. Digital, hearing aid improves the hearing capacity of hearing, impaired persons., , 1.6.4 Monitoring, , PHOTOGRAPHS, , Fig. 1.3, , A digital hearing aid employing signal processing, , technique (Siemens TRIANO 3 Digital hearing aid;, Embedded systems falling under this category are, Siemens Audiology Copyright© 2005), specifically designed for monitoring purpose. Almost, all embedded products coming under the medical, domain are with monitoring functions only. They, are used for determining the state of some variables, using input sensors. They cannot impose control, over variables. A very good example is the electro, cardiogram (ECG) machine for monitoring the, heartbeat of a patient. The machine is intended to do the, monitoring of the heartbeat. It cannot impose control, over the heartbeat. The sensors used in ECG are the, different electrodes connected to the patient’s body., Some other examples of embedded systems with, monitoring function are measuring instruments like, digital CRO, digital multimeters, logic analysers,, etc. used in Control & Instrumentation applications. Fig. 1.4 A patient monitoring system for monitoring, They are used for knowing (monitoring) the status of, heartbeat (Photo courtesy of Philips Medical Systems, (www.medical.philips.com/)), some variables like current, voltage, etc. They cannot, control the variables in turn., , Photographs of important concepts,, designs and architectural descriptions, bring the subject to life.

Page 22 :

xxii, , Visual Walkthrough, , ILLUSTRATIONS, Machine cycle (M1), S1, , S2, , S3, , S4, , S5, , Machine cycle (M2), S6, , T State, S1 S2, , S3, , S4, , S5, , S6, , Clock Cycles, P P P P P P P P P P P P P P P P P P P P P P P P, 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2, , ALE, , Effective and accurate Illustrations, demonstrate the concepts, design, problems and steps involved in the design, of embedded systems., , PSEN, RD, , PCH out, , P2, P0, , INST, in, , Fig. 6.10, , PCL, out, , INST, in, , DPH or P2 SFR out, ADDR, (DPL/Ri), out, , Data, in, , PCH out, PCL, out, , INST, in, , PCH ou, PCL, out, , Timing diagram for MOVX instruction when the program memory is external, , MOVX is a two machine cycle instruction. The opcode fetching starts at state-1 (S1) of the first machine, cycle and it is latched to the instruction register. A second program memory fetch occurs at State 4 (S4) of the, same machine cycle. Program memory fetches are skipped during the second machine cycle. This is the only, time program memory fetches are skipped. The instruction-fetch and execute sequence and timing remains, the same regardless the physical location of program memory (it can be either internal or external). If the, program memory is external, the Program Strobe Enable (PSEN) is asserted low on each program memory, fetch and it is activated twice per machine cycle (Fig. 6.10). Since there is no program fetch associated with, , CHAPTER SUMMARY AND KEYWORDS, , Summary, � There exists a set of characteristics which are unique to each embedded system., , LO1, , � Embedded systems are application and domain specific., , LO2, , � Quality attributes of a system represents the non-functional requirements that need to be, LO2, documented properly in any system design., � The operational quality attributes of an embedded system refers to the non-functional requirements, that needs to be considered for the operational mode of the system. Response, Throughput,, Reliability, Maintainability, Security, Safety, etc. are examples of operational quality LO2, attributes., � The non-operational quality attributes of an embedded system refers to the non-functional, requirements that needs to be considered for the non-operational mode of the system. Testability,, debug-ability, evolvability, portability, time-to-prototype and market, per unit cost and LO2, revenue, etc. are examples of non-operational quality attributes., � The product life cycle curve (PLC) is the graphical representation of the unit cost, product sales and, profit with respect to the various life cycle stages of the product starting from conception, LO2, to disposal., � For a commercial embedded product, the unit cost is peak at the introductory stage and it falls in, the maturity stage., LO2, � The revenue of a commercial embedded product is at the peak during the maturity stage. LO2, , Keywords, Reac ve system: An embedded system which produces changes in output in response to the changes in input, , [LO 1], Real-Time system: A system which adheres to strict ming behaviour and responds to requests in a known, amount of me, [LO 1], Quality a ributes: The non-func onal requirements that need to be addressed in any system design [LO 2], Response: It is a measure of quickness of the system, [LO 2], Throughput: The rate of produc on or opera on of a defined process over a stated period of me [LO 2], Reliability: It is a measure of how much % one can rely upon the proper func oning of a system, [LO 2], MTBF: Mean Time Between Failures–The frequency of failures in hours/weeks/months, [LO 2], MTTR: Mean Time To Repair–Specifies how long the system is allowed to be out of order following a failure, Time-to-prototype: A measure of the me required to prototype a design, [LO 2], Product life-cycle (PLC): The representa on of the different stages of a product from its concep on to disposal, , [LO 2], Product life cycle curve: The graphical representa on of the unit cost, product sales and profit with respect, to the various life cycle stages of the product star ng from concep on to disposal, [LO 2], , Summary: Each chapter ends with a LO, tagged summary to give learners a gist of, the chapter and help them have a quick, glance on the main points of a chapter, Keywords: A list of important terms, used in the chapter have been given to, help learners recapitulate what has been, dealt with in the various topics covered in, the chapter

Page 23 :

xxiii, , Visual Walkthrough, , OBJECTIVE AND REVIEW QUESTIONS, Objec ve Ques ons, , Readers can assess their knowledge by, answering the Objective Questions in, multiple-choice format. Review Questions, spur students to apply and integrate, chapter content. They are tagged with, LOs of the chapter, , 1. Which of the following is true about VxWorks OS, (a) Hard real-time (b) Soft real-time, (c) Multitasking, (d) (a) and (c), (e) (b) and (c), 2. A task is waiting for a semaphore for its operation. Under VxWorks task state terminology, the task is said, to be in _______ state, (a) READY, (b) RUNNING, (c) PEND, (d) SUSPEND, (e) None of these, 3. Under VxWorks kernel the state of a task which is currently executing is changed to SUSPEND. Which of, the following system call might have occurred?, (a) taskSpawn(), (b) taskActivate(), (c) taskSuspend(), (d) msgQSend(), (e) None of these, 4 U d V W k k, l h, f, k i SUSPEND Whi h f h f ll i, i, ?, , Review Ques ons, 1. What is EDLC? Why EDLC is essential in embedded product development?, , [LO 1], , 2. What are the objectives of EDLC?, [LO 1, LO 2], 3. Explain the significance of Productivity in embedded product development. Explain the techniques for, productivity improvements., [LO 3], 4. Explain the different phases of Embedded Product Development Life Cycle (EDLC)., 5. Explain the term ‘model’ in relation to EDLC., 6. Explain the different types of Product Development needs., , [LO 4], [LO 5], [LO 4], [LO 4], , 7. Explain the Product Re-engineering need in detail., 8. Explain the various activities performed during the Conceptualisation phase of an Embedded product, development, [LO 4], , LAB ASSIGNMENTS, Lab Assignments, 1. Write an Embedded C program for building a dancing LED circuit using 8051 as per the requirements, given below, (a) 4 Red LEDs are connected to Port Pins P1.0, P1.2, P1.4 and P1.6 respectively, (b) 4 Green LEDs are connected to Port Pins P1.1, P1.3, P1.5 and P1.7 respectively, (c) Turn On and Off the Green and Red LEDs alternatively with a delay of 100 milliseconds, (d) Use a clock frequency of 12 MHz, (e) Use Keil μVision IDE and simulate the application for checking the firmware, (f) Write the application separately for delay generation using timer and software routines, 2. Implement the above requirement in Assembly Language, 3. Write an Embedded C application for reading the status of 8 Dip switches connected to the Port P1 of, the 8051 microcontroller using μVision IDE. Debug the application using the simulator and simulate, the state of DIP switches using the Port simulator for P1, 4. Implement the above requirement in Assembly language, 5. Write an Embedded C program to count the pulses appearing on the C/T0 input pin of 8051, microcontroller for a duration of 100 milliseconds using μVision IDE, 6. Implement the above requirement in Assembly language, , To aid students conduct experiments in, the laboratory, Lab Assignments have, been provided at the end of relevant, chapters.

Page 24 :

xxiv, , Visual Walkthrough, , APPENDIX ON DIFFERENT FAMILY OF, MICROPROCESSORS AND CONTROLLERS, Appendix, , I, The Appendix section is intended to give, an overview of PIC & AVR family of, microcontrollers & ARM processor., , Overview of PIC, and AVR Family of, Microcontrollers and, ARM Processors, , INTRODUCTION TO PIC® FAMILY OF MICROCONTROLLERS, PIC® is a popular 8/16/32 bit RISC microcontroller family from Microchip Technology (www.microchip., com). The 8bit PIC family comprises the products PIC10F, PIC12F, PIC16F and PIC18F. They differ in, the amount of program memory supported, performance, instruction length and pin count. Based on the, architecture, the 8bit PIC family is grouped into three namely;, , Baseline Products based on the original PIC architecture. They support 12bit instruction set with very, limited features. They are available in 6 to 40 pin packages. The 6 pin 10F series, some 12F series (8 pin, 12F629) and some 16F series (The 20-pin 16F690 and 40-pin 16F887) falls under this category., Mid-Range This is an extension to the baseline architecture with added features like support for interrupts,, on-chip peripherals (Like A/D converter, Serial Interfaces, LCD interface, etc.), increased memory, etc. The, instruction set for this architecture is 14bit wide. They are available in 8 to 64 pin packages with operating, voltage in the range 1.8V to 5.5V. Some products of the 12F (The 8 pin 12F629) and the 16F (20-pin 16F690, and 40-pin 16F887) series comes under this category., , High Performance The PIC 18F J and K series comes under this category. The memory density for these, devices is very high (Up to 128KB program memory and 4KB data memory). They provide built-in support, for advanced peripherals and communication interfaces like USB, CAN, etc. The instruction set for this, architecture is 16bit wide. They are capable of delivering a speed of 16MIPS., As mentioned earlier we have a bunch of devices to select for our design, from the PIC 8bit family., Some of them have limited set of I/O capabilities, on-chip Peripherals, data memory (SRAM) and program, memory (FLASH) targeting low end applications. The 12F508 controller is a typical example for this. It, contains 512 × 12 bits of program memory, 25 bytes of RAM, 6 I/O lines and comes in an 8-pin package., On the other hand some of the PIC family devices are feature rich with a bunch of on-chip peripherals (Like, ADC, UART, I2C, SPI, etc.), higher data and program storage memory, targeting high end applications. The, 16F877 controller is a typical example for this. It contains 8192 × 14 bits of FLASH program memory, 368, bytes of RAM, 256 bytes of EEPROM, 33 I/O lines, On-chip peripherals like 10-bit A/D converter, 3-Timer, units USART Interrupt Controller etc It comes in a 40 pin package, , CASE STUDIES, Appendix, , II, , Design Case Studies, , 1. DIGITAL CLOCK, Design and Implement a Digital Clock as per the requirements given below., 1. Use a 16 character 2-line display for displaying the current Time. Display the time in DAY HH:MM:SS, format on the first line. Display the message ‘Have A Nice Day!’ on the second line. DAY represents, the day of the Week (SUN, MON, TUE, WED, THU, FRI and SAT). HH represents the hour in 2 digit, format. Depending on the format settings it may vary from 00 to 12 (12 Hour Format) or from 00 to 23, (24 Hour format). MM represents the minute in 2 digit format. It varies from 00 to 59. SS represents the, seconds in 2 digit format. It varies from 00 to 59. The alignment of display character should be centre, justified (Meaning if the characters to display are 12, pack it with 2 blank space each at right and left, and then display)., 2. Interface a Hitachi HD44780 compatible LCD with 8051 microcontroller as per the following interface, details, Data Bus: Port P2, Register Select Control line (RS): Port Pin P1.4, Read/Write Control Signal (RW): Port Pin P1.5, LCD Enable (E): P1.6, , A comprehensive set of five Case Studies,, at the end of the book demonstrate the, applications of theoretical concepts.

Page 25 :

PART-1, Embedded Systems:, Understanding the Basic Concepts

Page 26 :

Understanding the basic concepts is essential in the learning of any subject. Designing an Embedded, System is not a herculean task if you know the fundamentals. Like any general computing systems, Embedded, Systems also possess a set of characteristics which are unique to the embedded system under consideration., In contrast to the general computing systems, Embedded Systems are highly domain and application specific, in nature, meaning; they are specifically designed for certain set of applications in certain domains like, consumer electronics, telecom, automotive, industrial control, measurement systems etc. Unlike general, computing systems it is not possible to replace an embedded system which is specifically designed for an, application catering to a specific domain with another embedded system catering to another domain. The, designer of the embedded system should be aware of its characteristics, and its domain and application, specific nature., An embedded system is an electrical/electro mechanical system which is specifically designed for an, application catering to a specific domain. It is a combination of specialised hardware and firmware (software),, which is tailored to meet the requirements of the application under consideration. An embedded system, contains a processing unit which can be a microprocessor or a microcontroller or a System on Chip (SoC), or an Application Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC)/Application Specific Standard Product (ASSP) or a, Programmable Logic Device (PLD) like FPGA or CPLD, an I/O subsystem which facilitates the interfacing, of sensors and actuators which acts as the messengers from and to the ‘Real world’ to which the embedded, system is interacting, on-board and external communication interfaces for communicating between the, various on-board subsystems and chips which builds the embedded system and external systems to which, the embedded system interacts, and other supervisory systems and support units like watchdog timers, reset, circuits, brown-out protection circuits, regulated power supply unit, clock generation circuit etc. which, empower and monitor the functioning of the embedded system. The design of embedded system has two, aspects: The hardware design which takes care of the selection of the processing unit, the various I/O sub, systems and communication interface and the inter connection among them, and the design of the embedded, firmware which deals with configuring the various sub systems, implementing data communication and, processing/controlling algorithm requirements. Depending on the response requirements and the type of, applications for which the embedded system is designed, the embedded system can be a Real-time or a, Non-real time system. The response requirements for a real-time system like Flight Control System, Airbag, Deployment System for Automotive etc, are time critical and the hardware and firmware design aspects for, such systems should take these into account, whereas the response requirements for non-real time systems, like Automatic Teller Machines (ATM), Media Playback Systems etc, need not be time critical and missing, deadlines may be acceptable in such systems., Like any other systems, embedded systems also possess a set of quality attributes, which are the nonfunctional requirements like security, scalability, availability, maintainability, safety, portability etc. The, non-functional requirements for the embedded system should be identified and should be addressed properly, in the system design. The designer of the embedded system should be aware of the different non-functional, requirement for the embedded system and should handle this properly to ensure high quality., This section of the book is dedicated for describing the basic concepts of Embedded Systems. The chapters, in this section are organised in a way to give the readers a comprehensive introduction to ‘Embedded Systems,, their application areas and their role in real life’, ‘The different elements of a typical Embedded System’, the, basic lessons on ‘The characteristics and quality attributes of Embedded Systems’, ‘Domain and Application, specific usage examples for Embedded Systems’ and the ‘Hardware and Software Co-design approach for, Embedded System Design’, and a detailed introduction to ‘The architecture and programming concepts for, 8051 Microcontroller – The 8bit Microcontroller selected for our design examples’. We will start the section, with the chapter on ‘Introduction to Embedded Systems’

Page 27 :

Introduc on to Embedded Systems, , 1, , 3, , Introduction to, Embedded Systems, , LEARNING OBJECTIVES, LO 1, LO 2, LO 3, LO 4, , Know what an embedded system is, Differen ate between embedded and general compu ng systems, Underline the history of embedded systems, Classify embedded systems based on performance, complexity and the era in which, they evolved, LO 5 Explain the domains and areas of applica ons of embedded systems, LO 6 Iden fy the different purposes of embedded systems, LO 7 Analyse a real life example on the bonding of embedded technology with human, life, , Our day-to-day life is becoming more and more dependent on “embedded systems” and digital technologies., Embedded technologies are bonding into our daily activities even without our knowledge. Do you know the, fact that the refrigerator, washing machine, microwave oven, air conditioner, television, DVD players, and, music systems that we use in our home are built around an embedded system? You may be traveling by a, ‘Honda’ or a ‘Toyota’ or a ‘Ford’ vehicle, but have you ever thought of the genius players working behind the, special features and security systems offered by the vehicle to you? It is nothing but an intelligent embedded, system. In your vehicle itself the presence of specialised embedded systems vary from intelligent head lamp, controllers, engine controllers and ignition control systems to complex air bag control systems to protect, you from a severe accident. People experience the power of embedded systems and enjoy the features and, comfort provided by them. Most of us are totally unaware or ignorant of the intelligent embedded systems, giving us so much comfort and security. Embedded systems are like reliable servants–they don’t like to reveal, their identity and neither they complain about their workloads to their owners or bosses. They are always, working behind the scenes and are dedicated to their assigned task till their last breath. This book gives you, an overview of embedded systems, the various steps involved in their design and development and the major, domains where they are deployed.

Page 28 :

4, , Introduc on to Embedded Systems, , 1.1, , WHAT IS AN EMBEDDED SYSTEM?, , An embedded system is an electronic/electro-mechanical system designed to, perform a specific function and is a combination of both hardware and firmware, (software)., Every embedded system is unique, and the hardware as well as the firmware is, highly specialised to the application domain. Embedded systems are becoming an, inevitable part of any product or equipment in all fields including household appliances, telecommunications,, medical equipment, industrial control, consumer products, etc., LO 1 Know what, an embedded, system is, , 1.2, , EMBEDDED SYSTEMS VS. GENERAL COMPUTING SYSTEMS, , The computing revolution began with the general purpose computing, requirements. Later it was realised that the general computing requirements are not, sufficient for the embedded computing requirements. The embedded computing, requirements demand ‘something special’ in terms of response to stimuli, meeting, the computational deadlines, power efficiency, limited memory availability, etc., Let’s take the case of your personal computer, which may be either a desktop PC, or a laptop PC or a tablet PC. It is built around a general purpose processor like an Intel® Celeron/Core M or, a Duo/Quad* core or an AMD A-Series processor and is designed to support a set of multiple peripherals like, multiple USB 3.0 ports, Wi-Fi, ethernet, video port, IEEE1394, SD/CF/MMC external interfaces, Bluetooth,, etc and with additional interfaces like a DVD read/writer, on-board Hard Disk Drive (HDD), gigabytes of, RAM, etc. You can load any supported operating system (like Windows® 8.X/10, or Red Hat Linux/Ubuntu, Linux, UNIX etc) into the hard disk of your PC. You can write or purchase a multitude of applications for, your PC and can use your PC for running a large number of applications (like printing your dear’s photo using, a printer device connected to the PC and printer software, creating a document using Microsoft® Office Word, tool, etc.) Now, let us think about the DVD player you use for playing DVD movies. Is it possible for you, to change the operating system of your DVD? Is it possible for you to write an application and download it, to your DVD player for executing? Is it possible for you to add a printer software to your DVD player and, connect a printer to your DVD player to take a printout? Is it possible for you to change the functioning of, your DVD player to a television by changing the embedded software? The answers to all these questions are, ‘NO’. Can you see any general purpose interface like Bluetooth or Wi-Fi on your DVD player? Of course, ‘NO’. The only interface you can find out on the DVD player is the interface for connecting the DVD player, with the display screen and one for controlling the DVD player through a remote (May be an IR or any, other specific wireless interface). Indeed your DVD player is an embedded system designed specifically, for decoding digital video and generating a video signal as output to your TV or any other display screen, which supports the display interface supported by the DVD Player. Let us summarise our findings from the, comparison of embedded system and general purpose computing system with the help of a table:, LO 2 Differentiate, between embedded, and general, computing systems, , General Purpose Computing System, , Embedded System, , A system which is a combination of a generic hardware A system which is a combination of special purpose, and a General Purpose Operating System for executing a hardware and embedded OS for executing a specific set, variety of applications, of applications, (Contd.), *The illustration given here is based on the processor details available till Dec 2015. Since processor technology is undergoing rapid, changes, the processor names mentioned here may not be relevant in future.

Page 29 :

5, , Introduc on to Embedded Systems, , General Purpose Computing System, Contains a General Purpose Operating System (GPOS), , Embedded System, May or may not contain an operating system for functioning, , Applications are alterable (programmable) by the user (It is The firmware of the embedded system is pre-programmed, possible for the end user to re-install the operating system, and it is non-alterable by the end-user (There may be exceptions for systems supporting OS kernel image flashing, and also add or remove user applications), through special hardware settings), Performance is the key deciding factor in the selection of Application-specific requirements (like performance, power, the system. Always, ‘Faster is Better’, requirements, memory usage, etc.) are the key deciding, factors, Less/not at all tailored towards reduced operating power Highly tailored to take advantage of the power saving modes, requirements, options for different levels of power man- supported by the hardware and the operating system, agement., Response requirements are not time-critical, , For certain category of embedded systems like mission, critical systems, the response time requirement is highly, critical, , Need not be deterministic in execution behaviour, , Execution behaviour is deterministic for certain types of, embedded systems like ‘Hard Real Time’ systems, , However, the demarcation between desktop systems and embedded systems in certain areas of embedded, applications are shrinking in certain contexts. Smart phones are typical examples of this. Nowadays smart, phones are available with RAM 2 to 3 GB and users can extend most of their desktop applications to the, smart phones and it invalidates the clause “Embedded systems are designed for a specific application” from, the characteristics of the embedded system for the mobile embedded device category. However, smart phones, come with a built-in operating system and it is not modifiable by the end user. It makes the clause: “The, firmware of the embedded system is unalterable by the end user”, still a valid clause in the mobile embedded, device category., , 1.3, , HISTORY OF EMBEDDED SYSTEMS, , Embedded systems were in existence even before the IT revolution. In the olden, LO 3 Underline, days, embedded systems were built around the old vacuum tube and transistor, the, history of, technologies and the embedded algorithm was developed in low level languages., embedded, systems, Advances in semiconductor and nano-technology and IT revolution gave, way to the development of miniature embedded systems. The first recognised, modern embedded system is the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) developed by the MIT Instrumentation, Laboratory for the lunar expedition. They ran the inertial guidance systems of both the Command Module, (CM) and the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM). The Command Module was designed to encircle the moon, while the Lunar Module and its crew were designed to go down to the moon surface and land there safely., The Lunar Module featured in total 18 engines. There were 16 reaction control thrusters, a descent engine, and an ascent engine. The descent engine was ‘designed to’ provide thrust to the lunar module out of the lunar, orbit and land it safely on the moon. MIT’s original design was based on 4K words of fixed memory (Read, Only Memory) and 256 words of erasable memory (Random Access Memory). By June 1963, the figures, reached 10K of fixed and 1K of erasable memory. The final configuration was 36K words of fixed memory, and 2K words of erasable memory. The clock frequency of the first microchip proto model used in AGC

Page 30 :

6, , Introduc on to Embedded Systems, , was 1.024 MHz and it was derived from a 2.048 MHz crystal clock. The computing unit of AGC consisted, of approximately 11 instructions and 16 bit word logic. Around 5000 ICs (3-input NOR gates, RTL logic), supplied by Fairchild Semiconductor were used in this design. The user interface unit of AGC is known as, DSKY (display/keyboard). DSKY looked like a calculator type keypad with an array of numerals. It was used, for inputting the commands to the module numerically., The first mass-produced embedded system was the guidance computer for the Minuteman-I missile in, 1961. It was the ‘Autonetics D-17’ guidance computer, built using discrete transistor logic and a hard-disk for, main memory. The first integrated circuit was produced in September 1958 but computers using them didn’t, begin to appear until 1963. Some of their early uses were in embedded systems, notably used by NASA, for the Apollo Guidance Computer and by the US military in the Minuteman-II intercontinental ballistic, missile., , 1.4, , CLASSIFICATION OF EMBEDDED SYSTEMS, , LO 4 Classify, embedded systems, based on performance,, complexity and the era, in which they evolved, , It is possible to have a multitude of classifications for embedded systems,, based on different criteria. Some of the criteria used in the classification of, embedded systems are as follows:, (1), (2), (3), (4), , Based on generation, Complexity and performance requirements, Based on deterministic behaviour, Based on triggering., , The classification based on deterministic system behaviour is applicable for ‘Real Time’ systems. The, application/task execution behaviour for an embedded system can be either deterministic or non- deterministic., Based on the execution behaviour, Real Time embedded systems are classified into Hard and Soft. We will, discuss about hard and soft real time systems in a later chapter. Embedded Systems which are ‘Reactive’ in, nature (Like process control systems in industrial control applications) can be classified based on the trigger., Reactive systems can be either event triggered or time triggered., , 1.4.1, , Classification Based on Generation, , This classification is based on the order in which the embedded processing systems evolved from the, first version to where they are today. As per this criterion, embedded systems can be classified into the, following:, , 1.4.1.1 First Genera on The early embedded systems were built around 8bit microprocessors like, 8085 and Z80, and 4bit microcontrollers. Simple in hardware circuits with firmware developed in Assembly, code. Digital telephone keypads, stepper motor control units etc. are examples of this., , 1.4.1.2 Second Genera on These are embedded systems built around 16bit microprocessors and 8 or, 16 bit microcontrollers, following the first generation embedded systems. The instruction set for the second, generation processors/controllers were much more complex and powerful than the first generation processors/, controllers. Some of the second generation embedded systems contained embedded operating systems, for their operation. Data Acquisition Systems, SCADA systems, etc. are examples of second generation, embedded systems., 1.4.1.3 Third Genera on With advances in processor technology, embedded system developers started, making use of powerful 32bit processors and 16bit microcontrollers for their design. A new concept of

Page 31 :

Introduc on to Embedded Systems, , 7, , application and domain specific processors/controllers like Digital Signal Processors (DSP) and Application, Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs) came into the picture. The instruction set of processors became more, complex and powerful and the concept of instruction pipelining also evolved. The processor market was, flooded with different types of processors from different vendors. Processors like Intel Pentium, Motorola, 68K, etc. gained attention in high performance embedded requirements. Dedicated embedded real time and, general purpose operating systems entered into the embedded market. Embedded systems spread its ground, to areas like robotics, media, industrial process control, networking, etc., , 1.4.1.4 Fourth Genera on The advent of System on Chips (SoC), reconfigurable processors and, multicore processors are bringing high performance, tight integration and miniaturisation into the embedded, device market. The SoC technique implements a total system on a chip by integrating different functionalities, with a processor core on an integrated circuit. We will discuss about SoCs in a later chapter. The fourth, generation embedded systems are making use of high performance real time embedded operating systems, for their functioning. Smart phone devices, mobile internet devices (MIDs), etc. are examples of fourth, generation embedded systems., , 1.4.1.5, , What Next? The processor and embedded market is highly dynamic and demanding. So ‘what, will be the next smart move in the next embedded generation?’ Let’s wait and see., , 1.4.2, , Classification Based on Complexity and Performance, , This classification is based on the complexity and system performance requirements. According to this, classification, embedded systems can be grouped into the following:, , 1.4.2.1 Small-Scale Embedded Systems, , Embedded systems which are simple in application needs, and where the performance requirements are not time critical fall under this category. An electronic toy is a, typical example of a small-scale embedded system. Small-scale embedded systems are usually built around, low performance and low cost 8 or 16 bit microprocessors/microcontrollers. A small-scale embedded system, may or may not contain an operating system for its functioning., , 1.4.2.2 Medium-Scale Embedded Systems Embedded systems which are slightly complex in, hardware and firmware (software) requirements fall under this category. Medium-scale embedded systems, are usually built around medium performance, low cost 16 or 32 bit microprocessors/microcontrollers or, digital signal processors. They usually contain an embedded operating system (either general purpose or real, time operating system) for functioning., 1.4.2.3 Large-Scale Embedded Systems/Complex Systems Embedded systems which involve, highly complex hardware and firmware requirements fall under this category. They are employed in mission, critical applications demanding high performance. Such systems are commonly built around high performance, 32 or 64 bit RISC processors/controllers or Reconfigurable System on Chip (RSoC) or multi-core processors, and programmable logic devices. They may contain multiple processors/controllers and co-units/hardware, accelerators for offloading the processing requirements from the main processor of the system. Decoding/, encoding of media, cryptographic function implementation, etc. are examples for processing requirements, which can be implemented using a co-processor/hardware accelerator. Complex embedded systems usually, contain a high performance Real Time Operating System (RTOS) for task scheduling, prioritisation, and, management.

Page 32 :

8, , Introduc on to Embedded Systems, , 1.5, , MAJOR APPLICATION AREAS OF EMBEDDED SYSTEMS, , We are living in a world where embedded systems play a vital role in our dayto-day life, starting from home to the computer industry, where most of the, people find their job for a livelihood. Embedded technology has acquired a new, dimension from its first generation model, the Apollo guidance computer, to the, latest radio navigation system combined with in-car entertainment technology, and the wearable computing devices (Apple watch, Microsoft Band, Fitbit fitness, trackers etc.). The application areas and the products in the embedded domain are countless. A few of the, important domains and products are listed below:, (1) Consumer electronics: Camcorders, cameras, etc., (2) Household appliances: Television, DVD players, washing machine, fridge, microwave oven, etc., (3) Home automation and security systems: Air conditioners, sprinklers, intruder detection alarms, closed, circuit television cameras, fire alarms, etc., (4) Automotive industry: Anti-lock breaking systems (ABS), engine control, ignition systems, automatic, navigation systems, etc., (5) Telecom: Cellular telephones, telephone switches, handset multimedia applications, etc., (6) Computer peripherals: Printers, scanners, fax machines, etc., (7) Computer networking systems: Network routers, switches, hubs, firewalls, etc., (8) Healthcare: Different kinds of scanners, EEG, ECG machines etc., (9) Measurement & Instrumentation: Digital multimeters, digital CROs, logic analysers PLC systems, etc., (10) Banking & Retail: Automatic teller machines (ATM) and currency counters, point of sales (POS), (11) Card Readers: Barcode, smart card readers, hand held devices, etc., (12) Wearable Devices: Health and Fitness Trackers, Smartphone Screen extension for notifications, etc., (13) Cloud Computing and Internet of Things (IOT), LO 5 Explain the, domains and areas, of applications of, embedded systems, , 1.6, , PURPOSE OF EMBEDDED SYSTEMS, , LO 6 Identify the, different purposes, of embedded, systems, (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), (6), , As mentioned in the previous section, embedded systems are used in various, domains like consumer electronics, home automation, telecommunications,, automotive industry, healthcare, control & instrumentation, retail and banking, applications, etc. Within the domain itself, according to the application usage, context, they may have different functionalities. Each embedded system is, designed to serve the purpose of any one or a combination of the following tasks:, , Data collection/Storage/Representation, Data communication, Data (signal) processing, Monitoring, Control, Application specific user interface, , 1.6.1, , Data Collection/Storage/Representation, , Embedded systems designed for the purpose of data collection performs acquisition of data from the external, world. Data collection is usually done for storage, analysis, manipulation, and transmission. The term “data”, refers to all kinds of information, viz. text, voice, image, video, electrical signals and any other measurable, quantities. Data can be either analog (continuous) or digital (discrete). Embedded systems with analog data, capturing techniques collect data directly in the form of analog signals whereas embedded systems with, digital data collection mechanism converts the analog signal to corresponding digital signal using analog to, digital (A/D) converters and then collects the binary equivalent of the analog data. If the data is digital, it can, be directly captured without any additional interface by digital embedded systems.

Page 33 :

Introduc on to Embedded Systems, , 9, , The collected data may be stored directly in the system or may be transmitted to some other systems or it, may be processed by the system or it may be deleted instantly after giving a meaningful representation. These, actions are purely dependent on the purpose for which the embedded system is designed. Embedded systems, designed for pure measurement applications without storage, used in control and instrumentation domain,, collects data and gives a meaningful representation of the collected data by means of graphical representation, or quantity value and deletes the collected data when new data arrives at the data collection terminal. Analog, and digital CROs without storage memory are typical examples of this. Any measuring equipment used in the, medical domain for monitoring without storage functionality also comes under this category., Some embedded systems store the collected data for processing and analysis. Such systems incorporate a, built-in/plug-in storage memory for storing the captured data. Some of them give the user a meaningful, representation of the collected data by visual, (graphical/quantitative) or audible means using, display units [Liquid Crystal Display (LCD), Light, Emitting Diode (LED), etc.] buzzers, alarms, etc., Examples are: measuring instruments with storage, memory and monitoring instruments with storage, memory used in medical applications. Certain, embedded systems store the data and will not give, a representation of the same to the user, whereas, the data is used for internal processing., A digital camera is a typical example of an, embedded system with data collection/storage/, representation of data. Images are captured and the, captured image may be stored within the memory Fig. 1.1 A digital camera for image capturing/ storage/display, (Photo courtesy of Casio-Model EXILIM ex-Z850, of the camera. The captured image can also be, (www.casio.com)), presented to the user through a graphic LCD unit., , 1.6.2, , Data Communication, , Embedded data communication systems are deployed in applications ranging from complex satellite, communication systems to simple home networking systems., As mentioned earlier in this chapter, the data collected by an, embedded terminal may require transferring of the same to some, other system located remotely. The transmission is achieved, either by a wire-line medium or by a wireless medium. Wireline medium was the most common choice in all olden days, embedded systems. As technology is changing, wireless medium, is becoming the de-facto standard for data communication, in embedded systems. A wireless medium offers cheaper, connectivity solutions and make the communication link free, from the hassle of wire bundles. Data can either be transmitted, by analog means or by digital means. Modern industry trends, are settling towards digital communication., The data collecting embedded terminal itself can incorporate, Fig. 1.2 A wireless network router for data, data communication units like wireless modules (Bluetooth,, communication (Photo courtesy of Linksys, ZigBee, Wi-Fi, EDGE, GPRS, etc.) or wire-line modules (RS(www.linksys.com). A division of CISCO, 232C, USB, TCP/IP, PS2, etc.). Certain embedded systems, system)

Page 34 :

10, , Introduc on to Embedded Systems, , act as a dedicated transmission unit between the sending and receiving terminals, offering sophisticated, functionalities like data packetizing, encrypting and decrypting. Network hubs, routers, switches, etc., are typical examples of dedicated data transmission embedded systems. They act as mediators in data, communication and provide various features like data security, monitoring etc., , 1.6.3, , Data (Signal) Processing, , As mentioned earlier, the data (voice, image, video,, electrical signals, and other measurable quantities), collected by embedded systems may be used for, various kinds of data processing. Embedded systems, with signal processing functionalities are employed in, applications demanding signal processing like speech, coding, synthesis, audio video codec, transmission, applications, etc., A digital hearing aid is a typical example of an, embedded system employing data processing. Digital, hearing aid improves the hearing capacity of hearing, impaired persons., , 1.6.4, , Monitoring, , Fig. 1.3, , A digital hearing aid employing signal processing, technique (Siemens TRIANO 3 Digital hearing aid;, , Embedded systems falling under this category are, Siemens Audiology Copyright© 2005), specifically designed for monitoring purpose. Almost, all embedded products coming under the medical, domain are with monitoring functions only. They, are used for determining the state of some variables, using input sensors. They cannot impose control, over variables. A very good example is the electro, cardiogram (ECG) machine for monitoring the, heartbeat of a patient. The machine is intended to do the, monitoring of the heartbeat. It cannot impose control, over the heartbeat. The sensors used in ECG are the, different electrodes connected to the patient’s body., Some other examples of embedded systems with, monitoring function are measuring instruments like, digital CRO, digital multimeters, logic analysers,, etc. used in Control & Instrumentation applications. Fig. 1.4 A patient monitoring system for monitoring, They are used for knowing (monitoring) the status of, heartbeat (Photo courtesy of Philips Medical Systems, (www.medical.philips.com/)), some variables like current, voltage, etc. They cannot, control the variables in turn., , 1.6.5, , Control, , Embedded systems with control functionalities impose control over some variables according to the changes, in input variables. A system with control functionality contains both sensors and actuators. Sensors are, connected to the input port for capturing the changes in environmental variable or measuring variable. The

Page 35 :

11, , Introduc on to Embedded Systems, , actuators connected to the output port are controlled according to the changes in input variable to put an, impact on the controlling variable to bring the controlled variable to the specified range., Air conditioner system used in our home to, control the room temperature to a specified limit is a, typical example for embedded system for control, purpose. An airconditioner contains a room, temperature-sensing element (sensor) which may be, a thermistor and a handheld unit for setting up, (feeding) the desired temperature. The handheld unit, may be connected to the central embedded unit, Fig. 1.5 An Airconditioner for controlling room, residing inside the airconditioner through a wireless, temperature. Embedded System with Control, link or through a wired link. The air compressor unit, functionality, acts as the actuator. The compressor is controlled, (Photo courtesy of Electrolux Corpora on), according to the current room temperature and the, desired temperature set by the end user., Here the input variable is the current room temperature, and the controlled variable is also the room temperature. The, controlling variable is cool air flow by the compressor unit., If the controlled variable and input variable are not at the, same value, the controlling variable tries to equalise them, through taking actions on the cool air flow., , 1.6.6, , Application Specific User, Interface, , These are embedded systems with application-specific user, interfaces like buttons, switches, keypad, lights, bells, display, units, etc. Mobile phone is an example for this. In mobile, phone the user interface is provided through the keypad,, graphic LCD module, system speaker, vibration alert, etc., , 1.7, , Fig. 1.6 An embedded system with an applicationspecific user interface (Photo courtesy of, BlackBerry Smartphone Handsets, (amazon.com)), , WEARABLE DEVICES—THE INNOVATIVE BONDING, OF LIFESTYLE WITH EMBEDDED TECHNOLOGIES, , Wearable Devices/Wearables is a hot topic of discussion at the time of the first, revision of this book (Year 2015). Wearable Devices/Wearables refer to embedded, LO 7 Analyse a, technologies/systems which are incorporated into accessories (watch, bracelet,, real life example, ring, necklace, eye glass, headband, beanies, etc.) and apparels. Wearable, on the bonding, technology envisions the bonding of embedded technologies into our day-to-day, of embedded, life and is setting a new dimension to fashion and lifestyle. It empowers you, technology with, with the power of embedded computing and communication, keeping you always, human life, connected and alerted with things which you are most interested (e.g. Social, Feeds - Twitter, Facebook, etc., Instant Messages from your dear and near, tracking your fitness activities,, etc.), without compromising on the fashion aspects of your lifestyle.

Page 36 :

12, , Introduc on to Embedded Systems, , The calculator watch from Casio, introduced in the 1980s, was a classic example for the concept of, wearable device. In terms of the computing power, today's wearable devices are capable of performing many, of the same computing tasks as smartphones and tablets; and in some cases they can even outperform these, gadgets. While the term Wearables is generally used to specify a set of accessories and apparels which can be, put on and taken off easily, certain type of devices which are implanted into the body like smart tattoos, RFID, microchips etc. also falls under the broad definition of Wearables. The primary goal of wearable technologies, is to smoothly integrate functional, portable embedded computing devices into individuals’ day-to-day life to, provide constant, convenient, seamless integration (Information at a quick glance—View your social feeds, from Facebook, Twitter, etc. on the screen of a Smartwatch which is connected to your Smartphone and act as, a second screen for your phone) and hands-free access to other connected devices (e.g. Interact with a gaming, console or Music player App on a smartphone through simulated touch gestures from a wearable device like, smart ring). The majority of the wearable devices out there in the market today/proposed for future fall under, the Health and Fitness monitoring/Entertainment/Smartphone Accessory or feature extension category., What is inside a wearable device is solely dependent on the targeted end functionality. In general, wearable, device includes an embedded controller which acts as the master brain of the unit, a wireless Communication, subsystem [(Based on Wireless technologies like Bluetooth/Wi-Fi/NFC (Near Field Communication)/, Cellular, etc.)] for establishing data/voice communication with other electronic systems like Smartphones,, Laptops, Tablets, Gaming consoles, etc. Let us consider a concept Smartwatch which acts a normal watch, and at the same time has a bunch of sensors embedded into it to keep track of the various fitness activities, like number of steps taken and distance walked (Pedometer functionality), number of floors climbed etc., and to track and record vital signs like heart-rate. An embedded Processor/Microcontroller (Like ARM) will, act as the master controller unit, which interfaces with the on-board subsystems like sensor modules which, keep track of the various fitness activities and record the vital signals, wireless communication link like, Bluetooth for establishing communication channel with an interfacing device like Smartphone/Tablet. The, pedometer functionality is implemented through MEMS 3-D accelerometer sensor (e.g. LIS2DH from ST, Microelectronics). An Altimeter/Barometric sensor can be used for tracking the number of floors climbed., The heart rate monitoring functionality is implemented by the combination of an Optic/Photo sensor or, Pressure Sensor or Electrodes with an Analog Front End (AFE) chip (e.g. Analog Devices AD8232 AFE, chip) for signal conditioning. Depending on the volume of readings to be stored in the device, the device, may contain a few kilobytes to a few Megabytes of Flash (Storage) memory. An ultra-low power Bluetooth, transceiver is used for establishing a wireless communication interface with the device and it can talk to other, peripherals over standard Bluetooth profiles like (SPP - Serial Port Profile, MAP - Message Access Profile,, GATT - Generic Attribute Profile, etc.). Since the device is intended to work as a standalone, portable device, it will contain a battery (Mostly a rechargeable Li-lo battery) to power the unit and a battery charging and, monitoring subsystem to re-charge the battery and to keep track of the battery status., Fitbit Charge, Surge (www.fitbit.com), are examples of wearable devices for fitness and activity tracking., Sony SmartWatch 3 (http://www.sonymobile.com/us/products/smartwear/smartwatch-3-swr50/), Samsung, Galaxy Gear Series Smart watches are examples of wearable devices which provide the functionality of, a watch and at the same time acts an accessory/extension to your smartphone - Featuring Quick Glance, notifications, such as texts, emails social feeds, phone calls, hands-free calling all on your wrist. APPLE, WATCH announced in Sep 2014 is an example of a Wearable device which acts as an accessory to the, iPhone for providing notifications and content from apps and also integrates the functionality of a watch,, health and fitness tracking, mobile payment and many other niche features. Microsoft Band is a wearable, device which provides integration with multi-mobile-platforms (Windows/Android/iOS) for notifications, (Call, Text, Social Feeds etc.) and also acts a fitness tracker and health monitoring device. It integrates, multiple sensors (Optical Heart Rate sensor, 3-axis accelerometer/gyro, GPS, Ambient light sensor, Skin, temperature sensor, UV sensor, Galvanic skin response sensor, Barometer etc.) and tracks steps, heart rate,

Page 37 :