Page 1 :

MIGRATION OF BIRDS, , . ; Individual organisms often move about in their environment in response to a varied group, , of stimuli. When such. movements result in the temporary or permanent absence from one home, range and the establishment of a residence in another, the resulting movement is said to be a, migration (L., migrare = to travel). Migration is a periodic passing of animals from one place, to another (Cahn). Bird’s migration is a two-way journey, i¢., a regular, periodic, to-and-fro, movement of some birds between their summer and winter homes or from a breeding and nesting, place to a feeding and resting place., , Migratory and resident birds. Majority of birds have the inherent quality to move from, one place to another to obtain the advantages of the favourable condition. Such birds are called, migratory birds. Some birds such as bobwhite and ruffled sand grouse, however, do not migrate, at all and they remain throughout the year in a country. Such birds are called resident birds., Migratory birds cover thousands of miles in their periodic seasonal journeys. Migration is a, remarkable device to obtain the advantage of the favourable conditions in more northerly regions, only during the summer. Migration occurs during the particular period of the year and the birds, , usually follow the same route., , Kinds of Migrations, , The migratory birds migrate in a variety of ways and accordingly following kinds of avian, migrations have been recognised by different ornithologists :, , 1. Latitudinal migration. The latitudinal migration usually means the movement from north, to south and vice versa. Most birds live in the landmasses of the northern temperate and subarctic, zones where they get facilities for nesting and feeding during summer. During winter, when the, northern hemisphere becomes covered with ice and snow, these birds move towards South for, shelter. Several North American and Eurasian birds cross the equator to spend winter in deeper, and warmer parts of South America and Africa. The American golden plover (Pluvialis dominica), Passes the nine months of winter 8,000 miles south in the plains of Argentina, thus, enjoying, ‘Wo summers: each year and knows not a hint of winter. Ruff breeds at Siberia and travels to, Great Britain, Africa, plains of India and Sri Lanka, thus, travelling a distartce of 6,000 miles., , An opposite but lesser movement also occurs in the southern hemisphere when the seasons, te changed. Some tropical birds migrate to breed during rainy season to the outer tropics and, ‘lum to the central tropics in dry:season. Marine birds may also make extensive migrations., , © Arctic tem (Sterna) breeds in the north temperate zone, and migrates to the Antarctic along, , Sides of the Atlantic. Penguins make migrations by swimming. tee, Win Altitudinal migration. Altitudinal or vertical migrations from high mountains in the, Q Loy valleys in the winter occur in many Indian and foreign mountaineer birds. In India, , thousand Of species during summer migrate from planes to the slopes of Himalayas ascending, Com, ba Of feet above sea level and return to planes on the commencement of winter, €.g.,, the are toes Bush chat and Scolopax ruticola, Such altitudinal migration also a, , 8 and coots of Andes in Argentina, violet green swallows of Great Britain, and the

Page 2 :

; j. . we:, willow ptarmigan of Siberia. The brown plumage of willow ptarmigan turns white in win, diet of insects shifted to buds and twigs of alders and willows. ae, ongitudinal or east-west and vice-versa migration also occu:, ‘alkland Island, and south Patagonian in Septem!, , ter, any, , 3. Longitudinal migration. L, some birds. The Patagonian plover visits the F:, and October for breeding., , 4, Partial migrations. Many species, su, and northern United States and barn owls (Z)to a St ,, sedentary populations of the southern states, are only partial migrants. In such cases, al the, birds of a group of migratory birds do not leave the native land, visible throughout the Year, Actually these are partial migrants, because the birds visible in winter are not the same ag Ste,, in summer. Songthrush, redbreast, titmouse, finch, etc., " p, , 5. Erratic migration. The erratic, vagrant, irregular or wandering migration Occurs j, great blue heron, cuckoos, thrushes and warblers. In such birds, after breeding, the adults and, the young may stray from their home to disperse in all directions over many or a few hundr ed, miles in search of food and safety from enemies. Sometimes hurricanes take the sea birds Pp, far as 2000 miles away from home seas and there they die either due to exhaustion or due tg, , unknown shores., , 6. Seasonal migration. Some ornithologists of temperate countries have classified migratory, birds according to seasons. Thus, in Britain, swifts, swallows, nightingales.and cuckoos are summer, visitors, because they arrive in spring from the south, remain there to breed and leave for the, south in autumn. Some birds, such as fieldfare, snow bunting and redwing, are winter Visitors,, as they arrive in autumn, chiefly from north, stay throughout the winter, and fly northwards, again in spring. While some birds such as snipes and sandpipers are the birds of passage, seen, for short time twice a year on their way to colder or warmer countries in spring and autumn,, , Besides these kinds of avian migrations, following three kinds of migrations can also be, recognised in different birds :, , A. Climatic migrations occur as a result of daily or seasonal changes in the. climate of, the environment. The well known north-south migration of many, ducks and geese is a good, example of climatic migration., , B. Alimental migrations occur as a result of food or water shortages and may occur at, any time in a year. ; %, , ~» -C. Gametic migrations result from a need to occupy some special region or environment, for some part of the reproductive process. Most migratory birds perform gametic migration., , ch as blue birds and many blue jays of Can, [ba) migrate southwards to mingle with gt, , are partial migrants., , , , Modes of Flight in Migration, ‘During their migration, most migratory birds display following, significant features :, 1. Time of migratory flights. The most migratory birds either fly during daytime or nightfime.and accordingly following two types of migration can be recognised ::, (2) Diurnal migration. Some birds fly mainly by day, such as crows, swallows, robins,, blackbirds, hawks, blue-birds, jays, cranes, loons, pelicans, geese, ducks, swans, and other shore, birds. They may stop to forage in suitable places, but swallows and swifts capture their insect, food in the air as they travel. These diurnal migratory birds often travel in flocks, which m4, be) well-organised (ducks, geese and swans) or loose (swallows)., , ~ (6) Nocturnal migration. A vast majority of birds are nocturnal migrants. These incu?, mostly small-sized birds, such as Sparrows, warblers, thrushes, etc. These birds prefer to fly at nigh, under the protective cover of darkness, to escape their enemies. By flying’at night, they aivé ®, the daybreak; take rest, procure food during daytime and then start ‘again at the approach of ni", , , , , , , , }, |, , a

Page 3 :

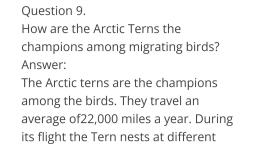

a Py De Range of migration. The range of migra, , (Moreau, 1972)., , the Himalayas at altitude of 2,000 feet or more., , tion commonly varies from one or few miles, 4 thousands of miles in different groups of migratory birds but it is almost constant for a, particular species. For example, the Himalayan snow partridges descend a few hundred feet and, . cover a distance of about one or two miles, Chicades travel (descend) about 8,000 feet, while, golden plovers, sandpipers, boblinks and swallows cover 6,000 to 9,000 miles from the Arctic, to the grassy plains of Argentina or the Patagonian beaches in South America. Arctic tern breeds, along the coast of Labrador in summer and then migrates to its home destination to the edges, of Antarctica in winter which is about 11,000 miles. It again returns in the summer to the coast, of Labrador travelling about the same distance. White stork of Europe migrates to South Africa, in winter taking a journey of about 8,000 miles. It is calculated that 5,000 million land birds, migrate from Europe to Africa each autumn and half of them succeed in returning next spring, , 3. Altitude of flight. Some birds fly quite close to the earth, while most routine migration, occurs within 3,000 feet .of the earth. Certain small land birds have been reported to fly in, night at 5,000 to 14,000 feet altitudes. Further, some avian species even cross the Andes and, , 4. Velocity during migration. The speed or velocity of flight of migratory birds varies, from individual to individual and. species to species. It is affected by the speed of air and its, direction, and it has been reported that birds travel faster during migration than at any other, time. The flight speeds of certain migratory birds has been tabulated in the following table :, , , , , , AN-T4se7eag FLicHt Speeps or Biros (AFTER WeTTY, 1962)., , , , , , , , , , , , ©" Species © Distance 7 Elapsed'time ~ _ © Miles, ; a oi 2 (miles) “Sof flight (Days) ~-")’ per day”, <>!) [ASpeed of return to nest after being experimentally displaced: © °°" 7 *, 1. Manx shear water 3293 “12.9 263, » 2. | Laysan albatross 3200 10.0 320, _ 3... White stork 1404 11.9 118, 4. Noddy tern 1081 5.0 216, 5. Homing pigeon 1007 1.5 671, 6. Alpine swift 1007 3.0 336, 7. Herring gull 870 41 212, »B,Speed in moving from one point to another during migration., 8. Arctic ten 8699 114 76, » 9. Slender-billed shear water 6835 53 129, 10, Short-billed dowitcher 2299 20 1s, 11. ‘Lesser-yellow legs 1926 7 275, 12. Peregrine falcon 994 21 47, | 3. Mallard 553 2 276, <!4 Tumstone 497 25 “19, , , , , , Nute fo lo, , bo During migration, thus, cranes, carrians, crows and finches fly with the speed of 30 miles per, a While cross-bill flies with the speed of 30 miles per hour. .The maximum speed recorded so, of mi E.C. Stuart is about 170-200 miles per hour (¢.g., Indian swifts). Birds cover hundreds, tly ay Nonstop in a day or a night with an average of about 500 miles. Migratory birds usually, i. © oF six hours per day and also take rest in between for drink and food. Golden plovers, , Onstop from Hudson Bay and Alaska to South America covering a distance of 2,400 miles., , Routes of migration. The migratory birds usually follow definite lines of flight. The, wed by them may be the same while going and returning back or may be different.

Page 4 :

The nocturnal small birds migrate with the general, to North along warm air currents, and in autumn, North. Change in their course occurs due to config', and intervening mountain ranges, etc. Different mig, during their migration :, , air flow. In spring it takes place fro, from North to South with the cog} int, uration of land, coastline, path of grea, f, , at 1, ratory birds may follow the following me, es, , feo Ste Sd i e kno, (a) Sea routes. Marine birds follow sea routes. The land birds ar are to cross ag Much, diate islands the distance covere,, , as 400 miles of ocean in a stroke but if there are interme! dma, be more. Certain birds have been scen crossing the Atlantic Ocean between Azores and Portugal, (900 miles) and the ocean between the continents of North America and Bermuda, ete,, , (b) Coastal routes. The coastal routes afford migration for a large number of migranis, Certain important migratory coastal routes are East Atlantic coastline, West Atlantic Coasting, East Pacific coastline, West Pacific coastline, East Indies coastline and West Indies coastline”, , (c) River-valley routes. While migrating from planes to hills and from hills to planes, the, migratory birds cross rivers and river-valleys falling in the way., , (d) Mountain ranges. Very rarely the birds cross mountain ranges., , The river valleys, mountain ranges and coastal routes provide good landmarks for the, migrating birds, which enable the birds to recognise and remember the routes and entrances to, the countries. Deviations in path sometimes occur due to configuration of land, coastline, course, of great rivers or intervening mountain chains., , 6. Segregation during migration. Some birds such as kingfishers, swifts, and night-hawks, travel in separate companies, but certain other birds such as swallows, vultures, blue birds, turkeys,, , -etc., usually travel in mixed companies of several species due to similarity in their size, method, of search of food, etc. In some avian species, the male and female individuals travel separately., _ Males arrive first to build the nests. The young birds usually accompany their mothers., , 7. Order of migration. During migration the birds follow a definite order which is strictly, - followed. Normally the adults migrate first and they are followed by youngs. It has been found, that urge of migration occurs due to the maturity of gonads which instigate them to migrate, towards their breeding, grounds. Adult birds return to the same general and even detailed places, at both ends of the journeys. Young birds mostly do not learn from their elders, indeed may leave, before them, flying off in a direction that is presumably genetically determined. Hence, the adults, with ripe gonads start the migration. During the return flight the order becomes reversed—the, young birds start first and follow the same path which their parents had followed while coming, from that place. In adult precedence, there is always a definite sequence, the adult males take, the lead, adult females next in order and the birds’ of the year follow them and in the end come, the weak and wounded birds., , 8. Regularity of migration. Several species of migratory birds show a striking regularity,, ‘year after year, in their timings of arrival and departure. In spite of long distances travelled of, vagaries of weather, they are often punctual within a day or two in their time of arrival. Further,, _ most migratory birds come back to the same breeding place year after year., , , , , , TET, , _ Problems of Migration, , ~~ The phenomenon of avian migration has remained an omithological riddle and its various, | aspects are still little understood. Certain scientific explanations have been forwarded from time !, , time to explain certain problematical issues concerning ‘the avian migration and they are fe, , following :, , iis Problem of way-finding or navigation. It is still a riddle that what guides the young, , ones of a migratory bird to migrate and follow the same course which their parents had take?:, , Probably it is genetically determined. Various explanations have been given for what determines, the direction and course of migration. | :

Page 5 :

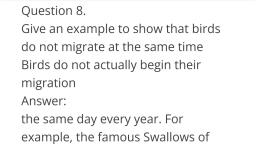

i) Topographic cues. To aphic . ee, y & fide ut : os Pographic cues can give long range guidance in daylight. The, gratory bir ls utilise various natural structures or to i i, , il astal lines; chai ales pographical features, such as great rivers,, er valleys, coasts s, Chains of oceanic islands tai k., sng their flight. Landmarks m , mountain ranges, ctc., as the landmarks, , S may be learned. Duck id ing i i, , ims inf ion fr ‘ . sand geese travelling in family groups, a mit the information from generation to generati i i, E Me eGeMast stages of homing 2 nera ion. Most birds make little use of landmarks, excep! et Svonce - ing. They navigate mainly by the sun and stars., , . “ ie encore aie have suggested that the birds learn by experience. Some, , older 3 Bethe unge y a tradition of following a path in past several years, become leaders, to guide the younger generations. However, birds certainly do not learn their migratory route, from elders, as some of them do not fly in flocks at all., , (it) Some ornithologists such as Von Middendroff and H.L. Yeaglev advanced the idea, that birds navigate through responses to the earth’s magnetic field and their inner ear reacts to, "the mechanical Coriolis effect produced by the rotation of the earth. But there is no evidence, that birds have some magnetic sense, etc., , (iv) The east-west and north-south gradients of gravity and the magnetic intensity are, ~ supposed to have some function in avian migration., , (v) Mathews (1955) and Sauer (1957). have emphasised the position of the sun (during, day time) or stars (during night) helps the birds to navigate along definite route. Experimental, ' evidences by creating artificial planetarium have shown that the shifting of the position of sun, causes a change of the migration during night., , et, , Kramer (1951) experiments on cage’ walhie, _ caged starlings show restlessness at times, _ when migration is due and flutter in the, "appropriate direction in relation to the sun., Kramer showed that. birds have a clock, that does this. It has been experimentally, "proved that pigeons return home after, ‘telease from a distant place even if they, “faye never been: there before, nor have, tad any previous training in returning A B, ‘ftom situations out of sight from the loft. Fig. 28.9, Gustav Kramer's experiment with starlings, ithews (1955) and others have shown ' to show that day migrants use sun as a, t upon release the birds fly off towards compass:, , home provided that they can see the sun., Navigation by starlight has been studied by following the direction of restlessness movements, Sfbirds in a planetarium. Warblers and others altered their directions when the stars were shifted., , ™ Stars change and presumably it is a pattern that is recognised., _ (vi) Telluric currents. According to some naturalists, homing instinct and telluric, long definite routes. It is probable that, , i. enable the migratory birds to migrate a, Migration in fact makes use of the wind. The economy of energy moving down, , has obvious selective value and this has made birds into very good meteorologists. Birds, , fly at the height wheré the wind is most favourable., , Inspite of the evidence for navigation by the sun and stars much remain uncertain. It is, i d what is responsible for the’ reversal, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , rds home. Robins (Erithacus) oriented their, , kn §, th. tor i ;, Stim ™ home ‘take up an initial bearing towa!, without visual cues. Particles of magnetite, , Ml activi, _) ~~ *tivity in the migratory direction even