Page 3 :

Originally published as Paulus: Leben und Denken, © 2003 by Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin / New, York. All rights reserved., English translation © 2005 by Baker Publishing Group, Published by Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287, www.bakeracademic.com, The publication of this work was supported by a grant from the, Goethe-Institut.

Page 4 :

Ebook edition created 2014, All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any, form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy,, recording—without the prior written permission of the, publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed, reviews., ISBN 978-1-4412-4200-6, Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at, the Library of Congress, Washington, DC., Unless otherwise noted, Scripture quotations are from the New, Revised Standard Version (NRSV) of the Bible, copyright ©, 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National, Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by, permission.

Page 5 :

Contents, Cover, Title Page, Copyright Page, Translator’s Preface, Preface to the German Edition, Abbreviations, Part One: The Course of Paul’s Life, and the Development of His Thought, 1. Prologue: Paul as Challenge and, Provocation, 1.1 Approaching Paul, 1.2 Reflections on Historiography, 1.3 Methodological “Handle”: Meaning, Formation in Continuity and Change, 2. Sources and Chronology for Paul’s, Life and Work: Definite and, Hypothetical, 2.1 Absolute Chronology, 2.2 Relative Chronology, 3. The Pre-Christian Paul: Open-Minded, Religious Zealot, 3.1 Background and Social Status

Page 6 :

4., , 5., , 6., , 7., , 3.2 Paul: Pharisee in the Diaspora, 3.3 The Religious and Cultural, Background of Paul’s Thought, 3.4 The Persecutor of the Earliest, Churches, The Call to Be Apostle to the Gentiles:, The New Horizon, 4.1 The Reports about the Damascus, Event, 4.2 Significance of the Damascus Event, The Christian Paul: A Volcano Begins, to Rumble, 5.1 Rehearsal and Coaching: Paul and, Early Christian Tradition, 5.2 Paul’s Bible, 5.3 First Steps as a Missionary, 5.4 Paul as Missionary of the Antioch, Church, The Apostolic Council and the, Incident at Antioch: The Problems, Remain Unresolved, 6.1 The Apostolic Council, 6.2 The Antioch Incident, Paul’s Independent Mission: The, Volcano Erupts, 7.1 Presuppositions of the Pauline Mission

Page 7 :

7.2 Beginnings of the Independent, Mission, 7.3 The Pauline School and the Structure, of Paul’s Work with the Churches, 7.4 The Self-Understanding of the Apostle, to the Gentiles, 7.5 The Development of Early Christianity, as an Independent Movement, 8. Paul and the Thessalonians:, Consolation and Confidence, 8.1 Prehistory and Initial Preaching, 8.2 The Theology of 1 Thessalonians, 8.3 The Ethic of 1 Thessalonians, 8.4 First Thessalonians as a Document of, Early Pauline Theology, 9. First Corinthians: High and True, Wisdom, 9.1 Conflict in Corinth, 9.2 The Wisdom of the World and the, Foolishness of the Cross, 9.3 The Power of the Spirit and the Purity, of the Community, 9.4 Freedom and Obligation in Christ, 9.5 The Power of the Spirit and Building, Up the Church, 9.6 The Resurrection of the Dead, 9.7 The Cross, Justification, and the Law

Page 8 :

10. Second Corinthians: Peace and War, 10.1 The Events between 1 and 2, Corinthians, 10.2 The Unity of 2 Corinthians, 10.3 Paul’s Life as Apostolic Existence, 10.4 The Glory of the New Covenant, 10.5 The Message of Reconciliation, 10.6 The Fool’s Speech, 11. Paul and the Galatians: Discovery in, Conflict, 11.1 Prehistory, 11.2 The Galatian Crisis, 11.3 The Doctrine of the Law and of, Justification in Galatians, 11.4 The Ethic of Galatians: Freedom, Active in Love, 11.5 Inclusive and Exclusive Doctrine of, Justification in Paul, 12. Paul and the Church in Rome: HighLevel Encounter, 12.1 The History and Structure of the, Roman Church, 12.2 The Letter to the Romans as a, Contextualized Document, 12.3 The Gospel of Jesus Christ, 12.4 Knowledge of God among Jews and, Gentiles

Page 9 :

12.5 The Righteousness of God, 12.6 Paul and the Old Testament, 12.7 The Presence of Salvation: Baptism, and Righteousness, 12.8 Sin, Law, and Freedom in the Spirit, 12.9 Paul and Israel, 12.10 The Shape of the New Life, 13. Paul in Rome: The Old Man and His, Work, 13.1 Prehistory: Paul en Route to Rome, 13.2 Philippians, 13.3 The Letter to Philemon, 13.4 Paul the Martyr, Part Two: The Basic Structures of, Pauline Thought, 14. The Presence of Salvation: The, Center of Pauline Theology, 15. Theology: The God Who Acts, 15.1 The One God Who Creates and, Concludes, 15.2 God as the Father of Jesus Christ, 15.3 God as the One Who Elects, Calls,, and Rejects, 15.4 The Gospel as God’s Eschatological, Good News of Salvation

Page 10 :

15.5 The Newness and Attractiveness of, the Pauline Talk of God, 16. Christology: The Lord Who Is Present, 16.1 Transformation and Participation as, the Basic Modes of Pauline, Christology, 16.2 Jesus Christ as Crucified and Risen, 16.3 Jesus Christ as Savior and Liberator, 16.4 Jesus as Messiah, Lord, and Son, 16.5 The Substitutionary Death of Jesus, Christ “for Us”, 16.6 The Death of Jesus Christ as Atoning, Event, 16.7 Jesus Christ as Reconciler, 16.8 Jesus Christ as God’s, Righteousness/Justice, 16.9 God, Jesus of Nazareth, and Early, Christology, 17. Soteriology: The Transfer Has Begun, 17.1 New Being as Participation in Christ, 17.2 The New Time between the Times, 18. Pneumatology: The Spirit Moves and, Works, 18.1 The Spirit as the Connectional, Principle of Pauline Thought, 18.2 The Gifts and Present Acts of the, Spirit

Page 11 :

18.3 Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, 19. Anthropology: The Struggle for the, Self, 19.1 Human Being and Corporeality: σῶμα, and σάρξ, 19.2 Sin and Death, 19.3 The Law, 19.4 Faith as the New Qualification of the, Self, 19.5 Centers of the Human Self, 19.6 The New Freedom, 20. Ethics: The New Being as Meaning, Formation, 20.1 Life within the Sphere of Christ:, Correspondence as Basic Ethical, Category, 20.2 The New Being in Practice, 21. Ecclesiology: The Church as a, Demanding and Attracting Fellowship, 21.1 Primary Vocabulary and, Foundational Metaphors of Pauline, Ecclesiology, 21.2 Structures and Tasks in the Church, 21.3 The Church as the Realm of Freedom, from Sin, 22. Eschatology: Expectation and, Memory

Page 12 :

22.1 The Future in the Present, 22.2 The Course of the Final Events and, Life after Death, 22.3 The Destiny of Israel, 22.4 Eschatology as Time Construal, 23. Epilogue: Pauline Thought as, Enduring Meaning Formation, , Selected Bibliography, I. Texts, II. Lexica, Dictionaries, Concordances,, Reference Works, III. Commentaries, Monographs, Essays,, Articles, Index of Subjects, Index of Greek Words and Phrases, Index of Modern Authors, Index of Ancient Sources, Notes, Back Cover

Page 13 :

Translator’s Preface, In recent years Udo Schnelle has perhaps, become best known for his works on the, Gospel and Letters of John.[1] Udo Schnelle’s, doctoral dissertation, however, was a study, of Paul’s theology of baptism, Gerechtigkeit, und Christusgegenwart: Vorpaulinische und, paulinische Tauftheologie (Göttinger, Theologische Arbeiten 24; Göttingen:, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1983); and he has, never ceased to be interested in the life,, letters, and theology of Paul, as attested by, his numerous articles listed in the, bibliography of this book and by the, extensive section on Paul in his introduction, to the New Testament, The History and, Theology of the New Testament Writings, (trans. M. Eugene Boring; Minneapolis:, Fortress, 1998). Now he has brought, together his work on Paul in a, comprehensive study that will take its place, among the standard works in the field. In my, judgment, it is the best single volume on, Paul’s life and work, providing to students

Page 14 :

and teachers at all levels a thorough survey, of all major issues, integrating a careful and, judicious engagement with the vast primary, and secondary literature and his own, balanced interpretation. I am thus very, pleased to facilitate its use in the Englishspeaking world., At the author’s and the publisher’s request,, I have augmented the bibliography with, English books and articles, mostly listing, books and articles comparable to the ample, German bibliography already present, for the, benefit of students who do not read German., I have also complied with the author’s and, publisher’s request that I occasionally, provide translator’s notes on the German, text reflecting the European context with, which the reader might not be familiar. In, both cases, I have kept my own contributions, to a minimum., A valuable aspect of the volume is its, extensive use of primary sources from the, Hellenistic world. After the death of Georg, Strecker, Schnelle assumed the editorship of, the Neuer Wettstein: Texte zum Neuen, Testament aus Griechentum und Hellenismus, (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1996). His citation of

Page 15 :

such texts as are found there and insight into, their relevance for New Testament, interpretation greatly enrich this study of, Paul. Except where otherwise indicated,, translations of Aelius Aristides, Apostolic, Fathers, Apuleius, Cicero, Dio Chrysostom,, Diogenes Laertius, Epictetus, Euripedes,, Eusebius, Homer, Iamblichus, Josephus,, Lucian, Menander, Musonius Rufus, Ovid,, Philostratus, Plato (Gorgias, Resp.), Plutarch,, Quintilian, Res gestae divi Augusti, Seneca,, Sophocles, Suetonius, Tacitus, and Xenophon, are from the Loeb Classical Library editions, listed in the bibliography., This translation has been read by the, author, Udo Schnelle, and by James Ernest,, Joe Carey, and Paul Peterson for Baker, Academic, all of whom have made helpful, suggestions for which I hereby express my, heartfelt thanks.

Page 16 :

Preface to the German Edition, The goal of this book is to present a, comprehensive introduction to the life and, thought of the apostle Paul. It is intended as, a textbook that takes a didactic perspective, on the material as a whole and documents all, important positions in Pauline research. At, the same time, it is an independent, contribution to the ongoing debate, outlining, my own position on disputed points., Since each section can be read as an, independent unit, intended to be, understandable on its own, some overlapping, and repetition were unavoidable. I have, attempted to reduce these to a minimum,, although experience has taught that, textbooks are usually not read straight, through—and thus some repetition is in fact, necessary and helpful., I here express my gratitude to Dr. Michael, Labahn and Dr. Manfred Lang, my coworkers, at the University of Halle-Wittenberg, for, their continuing expert advice as well as for, their help in correcting the proofs. I am, grateful to Dr. Claus-Jürgen Thornton not

Page 17 :

only for his customary good care regarding, publication details but also for his, discussions regarding the contents of this, book., Halle, November 2002, Udo Schnelle

Page 18 :

Abbreviations, General, Abbreviations, , ca., ch(s)., col(s)., diss., ed(s)., e.g., enl., esp., ET, et al., exp., f(f)., frg., i.e., ibid., lit., LXX, NF, NIV, NRSV, p(p)., , circa, chapter(s), column(s), dissertation, editor(s), edited by, exempli gratia, for example, enlarged, especially, English translation, et alii, and others, expanded, and the following one(s), fragment, id est, that is, ibidem, in the same place, literally, Septuagint (the Greek Old Testament), Neue Folge, New Series, New International Version, New Revised Standard Version, page(s)

Page 19 :

par., passim, pl., rev., sc., v(v)., viz., , parallel (to indicate textual parallels), here and there, plural, revised (by), scilicet, namely, verse(s), videlicet, namely

Page 20 :

Primary Sources

Page 21 :

Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, , As. Mos., 2 Bar., 1 En., 2 En., Jos. Asen., Jub., L.A.B., L.A.E., Let. Aris., Pss. Sol., Sib. Or., T. Benj., T. Dan, T. Iss., T. Jos., T. Levi, T. Naph., T. Sim., , Assumption of Moses, 2 Baruch (Syriac Apocalypse), 1 Enoch (Ethiopic Apocalypse), 2 Enoch (Slavonic Apocalypse), Joseph and Aseneth, Jubilees, Liber antiquitatum biblicarum (Pseudo-Philo), Life of Adam and Eve, Letter of Aristeas, Psalms of Solomon, Sibylline Oracles, Testament of Benjamin, Testament of Dan, Testament of Issachar, Testament of Joseph, Testament of Levi, Testament of Naphtali, Testament of Simeon, , Dead Sea Scrolls and Related Texts, , CD, 1QH, , Cairo Genizah copy of the Damascus, Document, Hodayot or Thanksgiving Hymns

Page 23 :

Philo, , Abraham, Alleg. Interp., 1, 2, 3, Confusion, Creation, Decalogue, Dreams 1, 2, Drunkenness, Embassy, Flaccus, Flight, Giants, Heir, Migration, Moses 1, 2, Names, Planting, Posterity, Prelim., Studies, QE 1, 2, Sobriety, Spec. Laws 1,, 2, 3, 4, Unchangeable, Virtues, Worse, , On the Life of Abraham, Allegorical Interpretation 1, 2, 3, On the Confusion of Tongues, On the Creation of the World, On the Decalogue, On Dreams 1, 2, On Drunkenness, On the Embassy to Gaius, Against Flaccus, On Flight and Finding, On Giants, Who Is the Heir?, On the Migration of Abraham, On the Life of Moses 1, 2, On the Change of Names, On Planting, On the Posterity of Cain, On the Preliminary Studies, Questions and Answers on Exodus 1, 2, On Sobriety, On the Special Laws, That God Is Unchangeable, On the Virtues, That the Worse Attacks the Better

Page 26 :

New Testament Apocrypha and, Pseudepigrapha, , Ep. Paul, Sen., , Epistles of Paul and Seneca

Page 27 :

Other Early Christian Writers

Page 31 :

Classical Authors

Page 67 :

2, Sources and Chronology for Paul’s, Life and Work Definite and, Hypothetical, , Every event is bound to a particular place, and time. The extant Pauline letters,, however, name neither the place nor time of, their composition.[1] Acts, it is true, gives, extensive descriptions of Paul’s missionary, work, but here too we find no information on, when and where Paul composed his letters., Luke does not place events important for, early Christian history such as the apostolic, council and the call of Paul in a chronological, framework. Likewise we can only infer, indirectly the year when the apostle to the, Gentiles was born and the year he died. This, is why it is so difficult to establish a, chronology for Paul’s life and work and why, scholarly opinion on this issue is so, divergent. Nonetheless, any presentation of, the life and work of the apostle Paul,

Page 68 :

including any treatment that attempts to deal, only with its content, will depend on some, implicit or explicit chronology, and so we, must begin by discussing this topic. As we, develop this presentation, the goal is to, establish a temporal framework within which, we can integrate the central events of the, vita Pauli and his letters., In terms of method,[2] the historian’s point, of departure is the self-evident principle that, primary sources always receive priority. We, should thus always prefer the chronological, data that one can glean from the undisputed, Pauline letters when they are in tension or, contradiction to other New Testament, reports. We are not thereby disparaging the, historical value of Acts, but when Acts and, the undisputed Pauline letters contradict, each other, we should follow the letters. On, the other hand, when the information from, Acts and Paul’s letters can be combined, we, obtain a solid basis for Pauline chronology., When Acts is the only source for events from, the life of Paul, then one must probe the, extent to which Luke transmits reliable older, tradition or whether his presentation derives, from his own redactional composition.

Page 69 :

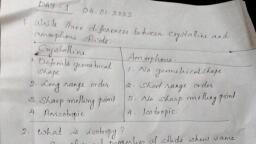

The obvious starting point for ascertaining, an absolute chronology consists of the few, places where the New Testament mentions, events that make contact with the general, data of world history documented by, extracanonical sources or archaeological, discoveries. This absolute chronology then, provides the foundation on which we may, construct the relative chronology of Paul’s, life and work., 2.1 Absolute Chronology Two events, enable us to reconstruct an, absolute chronology of Paul’s, activity: the expulsion of Jews, from Rome by Claudius (cf. Acts, 18:2b) and the date when Gallio, served as proconsul in Achaia., The Edict of Claudius Suetonius, (Divus Claudius 25.4) reports that, the emperor Iudaeos impulsore, Chresto assidue tumultuantis Roma, expulit (expelled the Jews from, Rome because, instigated by, Chrestus, they were constantly

Page 70 :

creating disturbances).[3] This, event was dated by the later, Christian historian Orosius (fifth, century CE) to the ninth year of, Claudius’s reign (49 CE).[4] When, Claudius died in October 54 CE, the, edict was annulled.[5], The Gallio Inscription The time, when Lucius Gallio, the brother of, Seneca, was in office as the, proconsul of Achaia may be, determined with a fair degree of, accuracy from an inscription, documenting a letter from the, emperor Claudius to the city of, Delphi. The text correlates the date, of its composition with the twentysixth acclamation of Claudius as, emperor. Although the twenty-sixth, acclamation itself cannot be exactly, dated, data from other inscriptions, document that the twenty-seventh, acclamation had already taken, place by August 1, 52 CE.[6] The, letter is addressed to Gallio’s, successor (Gallio is mentioned in

Page 71 :

the text in the nominative case; cf., line 6 from the top, Γαλλίων)[7] and, must therefore have been written, in the summer of 52. Since, proconsuls of senatorial provinces, were usually in office one year, we, may infer that Gallio was proconsul, of Achaia from the early summer of, 51 to the early summer of 52.[8], Since Prisca and Aquila were, expelled from Rome and came to, Corinth “not long” before Paul, (Acts 18:2, προσφάτως), the apostle, himself came to Corinth in the year, 50. If one combines this with the, information in Acts 18:11, Paul, stayed one and a half years in, Corinth. Assuming that the Jews, would have brought complaints, against Paul soon after the new, proconsul entered office, we can, date the Gallio scene of Acts 18:12–, 16 to the summer of 51.[9], 2.2 Relative Chronology Paul’s, arrival in Corinth at the beginning

Page 72 :

of the year 50 provides a firm, point from which the relative, chronology of Paul’s activity can, be calculated both forwards and, backwards. The goal is to establish, a temporal framework within, which the central events of the, vita Pauli and his letters can be, integrated., Events Prior to Corinth We must, begin with a reconstruction of the, events prior to Paul’s arrival in, Corinth. In the Acts account Paul’s, stay in Corinth was part of the, great Pauline mission in Asia Minor, and Greece (the second missionary, journey of Acts 15:36–18:22). We, can reconstruct a list of individual, missionary stations on the basis of, the traditions reworked by Luke., Their journey first took Paul and, Silas to the congregations that, already exist in Syria and Cilicia, (cf. Acts 15:40–41; also 15:23/Gal., 1:21). Then Paul came to Derbe, and Lystra, where he converted

Page 73 :

Timothy (cf. 1 Cor. 4:17)., Thereafter Paul and his coworkers, proceeded through Phrygia and the, Galatian country (Acts 16:6); from, there they launched their mission, in Europe. Philippi was the first, station (Acts 16:11–12a; Phil., 4:15ff.); from there Paul proceeded, to Thessalonica (Acts 17:1), then, via Beroea to Athens (cf. Acts, 17:10, 15). Early in the year 50, Paul journeyed from Athens to, Corinth (cf. Acts 18:1). Paul’s, letters confirm the basic outline of, these travels. Paul himself reports, that he founded the congregation, in Thessalonica after coming from, Philippi (cf. 1 Thess. 2:2). His stay, in Athens is also documented by 1, Thess. 3:1, so that both Acts and 1, Thessalonians confirm the, following order of stations on, Paul’s journey: Philippi,, Thessalonica, Athens, Corinth.[10], The missionary activity here, portrayed occupied about a year, and a half,[11] which brings one

Page 74 :

very near to the time of the, incident in Antioch and the, apostolic council, which preceded, it. We can date these two events to, the first half of 48 CE.[12], According to Paul’s account in Gal. 2:1–14,, the Antioch incident occurred in direct, proximity to the apostolic council. Granted,, Paul does not explicitly place the two events, in chronological order, but the sequencing of, the text in Galatians and the Pauline line of, argument suggest a strictly temporal, succession of events. The Antioch incident, thus falls in the summer of 48, after Paul and, Barnabas had returned from Jerusalem and, were staying in Antioch (cf. Acts 15:35)., In the portrayal of Paul’s activities from his, conversion to the apostolic council, there is, considerable divergence between Acts and, the undisputed Pauline letters. In Gal. 1:6–, 2:14 Paul gives a survey of his missionary, work up to the apostolic council. In the first, place, he emphasizes (Gal. 1:17) that after, his conversion he did not go directly to, Jerusalem but to Arabia and then returned to, Damascus.[13] The apostle wants this

Page 75 :

comment to underscore his independence, from the original congregation in Jerusalem,, and so the temporal connection in Gal. 1:18, (ἔπειτα µετὰ ἔτη τρία [three years later]), probably refers to his conversion. It was only, after this relatively long period that Paul, came to Jerusalem, where he stayed only, fifteen days with Cephas and also saw James, the Lord’s brother. After this first Jerusalem, visit Paul remained in Syria and Cilicia, far, from Jerusalem, and only “afterwards,, fourteen years later” (Gal. 2:1, ἔπειτα διὰ, δεκατεσσάρων ἐτῶν), did he visit Jerusalem for, the second time, with Barnabas and Titus on, the occasion of the apostolic council. The, reference to “fourteen years” in Gal. 2:1, probably refers to the first Jerusalem visit., [14] Paul confirms this himself by the, comment that he “went up again” (πάλιν δὲ, ἀνέβην) to Jerusalem. Since, in the ancient, calculation of time, the year that had begun, was counted as a full year, we may construct, the following outline of Paul’s activities from, his conversion to the apostolic council. The, apostolic council in the spring of 48 was, preceded by missionary activity in Syria and, Cilicia for about thirteen years, which had

Page 76 :

two phases: Paul probably remained for, about six years in the area of Tarsus and, Cilicia and then about 42 CE joined forces, with the missionary program sponsored by, the church in Antioch.[15] Paul’s first visit to, the church in Jerusalem falls in the year 35, CE. His visit to Arabia probably took place in, 34, so that two years elapsed between his, conversion in 33 and his first visit to, Jerusalem. The year 33 as the date of Paul’s, call and commissioning near Damascus fits, well with the presumed date of the death of, Jesus, the 14th of Nisan (April 7) of 30 CE., [16] This date for Jesus’ death is supported, by two arguments: (1) both the calculations, based on astronomy and the traditions about, the date of Jesus’ death support the, hypothesis that in 30 CE the 14th of Nisan, fell on a Friday; (2) according to Luke 3:1–2,, John the Baptist made his public appearance, in 27/28, and this was also the date of the, beginning of Jesus’ public ministry, which, lasted two or three years. A period of about, three years between Jesus’ crucifixion and, Paul’s conversion corresponds to the, missionary history of early Christianity, for, Paul’s actions as a persecutor presuppose a

Page 77 :

progressive expansion of the Christian, movement., The contradictions between the data in, Gal. 1–2 and the testimony of Acts pose the, central problem for a chronology of Paul’s, life and work: although Paul in Gal. 1:17, emphasizes that after his conversion he did, not go directly to Jerusalem, according to, Acts 9:26 he goes to Jerusalem immediately, after his flight from Damascus. The portrayal, in Acts corresponds to Luke’s ecclesiology,, for the evangelist is interested in the unity of, the developing church, which is here, expressed in an exemplary fashion by Paul, immediately establishing contact with the, Jerusalem apostles.[17] Whereas in Gal. 1:18, Paul speaks of only one trip to Jerusalem, prior to the apostolic council, in Acts he had, already been in Jerusalem a second time, before the council (11:27–30). Here, too, we, should follow Paul’s own testimony,, especially since this second trip fits in with, Luke’s ecclesiology. In Acts 11:27–30 Luke is, reworking individual elements of tradition in, a way that emphasizes the continuity of, salvation history and the unity of the church., Since in Acts 11:19–26 he has just reported

Page 78 :

on the founding of the congregation in, Antioch, he now immediately adds in 11:27–, 30 that contacts were established between, the new congregation in Antioch and the, original church in Jerusalem.[18] For Luke,, Paul’s journeys to Jerusalem are a, compositional strategy used to illustrate the, spread of the gospel in the world. They stand, in the service of his ecclesiology and provide, the framework within which Luke reworked, the extensive traditions available to him. The, one great trip of Jesus to Jerusalem in the, Gospel of Luke (cf. Luke 9:51–19:27), the five, trips to Jerusalem by the missionary to the, Gentiles (Acts 9:26; 11:27–30; 15:2, 4; 18:22;, 21:15), and the journey of the martyr Paul to, Rome form a unity for Luke. Historically,, however, Paul’s own testimony that as a, Christian missionary he was in Jerusalem, only three times is no doubt correct., Whereas in Gal. 1:21 Paul speaks only of, missionary activity prior to the apostolic, council in the region of Syria and Cilicia,, Acts 13–14 reports missionary work on, Cyprus and in Pamphylia, Pisidia, and, Lycaonia in Asia Minor. Is Acts’ report of a, first missionary journey thus only a “model

Page 79 :

mission”?[19] This is not a clear “yes or no”, question. Although we must regard a, missionary project on Cyprus as, improbable[20] and we cannot easily, harmonize the Pauline mission in Pamphylia,, Pisidia, and Lycaonia with Gal. 1:21.[21], Paul, on the other hand, is not intending in, the Galatian passage to provide an extensive, discussion of the individual stations of his, mission but is only emphasizing his, independence from Jerusalem. Moreover, the, Lukan account in Acts 13–14 contains, numerous traditions that speak for the, historicity of the first missionary journey in, the years 45–47.[22], Events after Corinth If the Gallio, scene provides a point of departure, for the absolute chronology and, thus facilitates a relatively sure, dating of the main stations of, Paul’s missionary work as far back, as his conversion, on this basis we, may now sort out the chronology of, the Pauline mission in relation to, Paul’s stay in Corinth as pictured, in Acts 18:1–17. The summarized

Page 80 :

travel report in Acts 18:18–23,, however, already raises big, problems. Paul at first remains, some days in Corinth, then travels, to Syria. He leaves the married, couple Prisca and Aquila in, Ephesus, has discussions with Jews, in the synagogue, turns down their, suggestion to remain in Ephesus, for missionary work, and leaves, Ephesus. Although Acts 18:18, names Syria as the actual, destination of Paul’s journey, in, 18:22 he lands in Caesarea, “goes, up” (ἀναβάς) to Jerusalem, and then, proceeds from Jerusalem to, Antioch.[23] Up to the point when, Prisca and Aquila move from, Corinth, these junctures in Paul’s, travels are undocumented in Paul’s, own letters. We also cannot find, there a satisfactory explanation for, the route and motivation for this, trip. Why would Paul leave his, successful mission work in, Macedonia and Asia Minor in order, to make a trip to Antioch? Nor is

Page 81 :

there an explanation for Paul’s, landing in Caesarea and visiting, Jerusalem, when according to Acts, 18:18 Syria is his destination and, Acts 18:22 gives Antioch as his real, goal. Explaining the landing in, Caesarea as due to unfavorable, winds[24] is hardly more than a, makeshift solution. Moreover, the, fourth Jerusalem visit in Luke’s, enumeration can hardly be, historical,[25] for it is opposed to, Paul’s own statements in the, letters. But what justification is, there for striking Jerusalem from, Acts 18:22 and still maintaining, Caesarea and Antioch as original?, On the other hand, the pre-Lukan, tradition spoke of a trip by the, apostle to Antioch, from where he, visited the Galatian country and, Phrygia en route to Ephesus. After, all attempts to connect the, traditions reworked in Acts 18:18–, 23 to a different Jerusalem trip, have proven unsuccessful,[26] one, must be satisfied with the insight

Page 82 :

that, according to the tradition, available to Luke, Paul, in, connection with his stay in Corinth,, first returned to Antioch and from, there made his way to Ephesus., Even if we should regard these, particulars as historical, we cannot, see this trip as including a visit to, Jerusalem., The reconstruction of Paul’s mission in, Ephesus is burdened with less uncertainty, (Acts 19). The trips described in Acts 18:18–, 23 occupied the time from summer 51 to, spring 52, after which Paul remained in, Ephesus about two years and nine months, (cf. Acts 19:8, 10; 20:31), from the summer, of 52 until the spring of 55. Paul then left, Ephesus in order to make the trip through, Macedonia to Corinth, gathering the, collection for the poor Christians in, Jerusalem and Judea. According to Acts, 19:21 and 1 Cor. 16:5, Paul intended to, travel through Macedonia to Corinth. Acts, 20:1–3 also gives Corinth as Paul’s, destination, where Paul arrived early in 56, and remained three months (cf. Acts 20:3).

Page 83 :

Originally Paul intended to travel by ship, directly to Syria. Some Jews hindered this, plan, and so he had to backtrack through, Macedonia. This information in Acts 20:3 is, in tension with Rom. 15:25, where Paul, announces a trip back to Jerusalem in order, to deliver the collection. Romans 15:25,, however, does not speak of a trip directly, from Corinth to Jerusalem, so that one need, not understand the information in Acts as, contradicting Paul’s own testimony., According to Acts 20:6, Paul traveled from, Corinth to Philippi, then to Troas, and from, there via Assos to Miletus. He then continued, his trip to Caesarea by ship in order to reach, Jerusalem by Pentecost of 56 CE (cf. Acts, 20:16).[27], The date Festus succeeded Felix as, procurator, as described in Acts 24:27, is, decisive for establishing the later Pauline, chronology. According to Acts 24:10, Felix, had already been procurator for some years,, and Paul had already spent two years in, prison when Festus began his administration., Felix’s time in office probably began in 52/53, (cf. Josephus, J.W. 2.247),[28] but the date of, his departure is disputed (either 55,[29] 58,

Page 84 :

or 59 CE[30]). Josephus (J.W. 2.250–270), dates the events associated with Felix to the, reign of Nero. If Nero began to rule in, October 54, it would have been necessary for, all the events mentioned by Josephus to, happen very quickly in order to have been, complete by 55.[31] It is therefore better to, assume that Festus’s administration began in, 58,[32] which also fits well with Acts 24:1,, since the high priest Annas (Ananus), mentioned there was in office about 47–59., [33] Since Paul had appealed to Caesar, during his trial before Festus (cf. Acts, 25:11), it was probably still in 58 that he was, sent to Rome on a prisoner transport led by a, centurion (cf. Acts 27:1–28:16).[34] If the, trip to Rome fell in the winter of 58–59, then, Paul would have entered the capital of the, empire in the spring of 59.[35] Acts 28:30, indicates that Paul as a prisoner was, relatively free and that he preached in his, residence for two years without hindrance., The year of Paul’s death is unknown; one can, only suppose that during the persecution of, Christians under Nero in the year 64, Paul, died as a martyr in Rome (cf. 1 Clem. 5.5–7)., [36]

Page 85 :

Chronology of Paul’s Life and Work, Death of Jesus, , 30, , Conversion of Paul, 33, First visit to Jerusalem, 35, Paul in Cilicia, ca. 36–42, Paul in Antioch, ca. 42, First missionary journey ca. 45–47, Apostolic council, 48 (spring), Incident in Antioch, 48 (summer), Second missionary, 48 (late summer)–51/52, journey, Paul in Corinth, 50/51, Gallio in Corinth, 51/52, Trip to Antioch, 51/52, Third missionary journey 52–55/56, Stay in Ephesus, 52–54/55, Paul in Macedonia, 55, Last stay in Corinth, 56 (early in the year), Arrival in Jerusalem, 56 (early summer), Imprisonment in Caesarea 56–58, Change of office,, 58, Felix/Festus, Arrival in Rome, 59, Death of Paul, 64

Page 86 :

4, The Call to Be Apostle to the Gentiles, The New Horizon, , Unanticipated events accelerate the course, of history. What has gone before suddenly, looses its attraction; something new begins, to move people and comes on stage as a, surprise., 4.1 The Reports about the Damascus, Event, What happened to Paul in the year 33 CE, in the neighborhood of Damascus?[1] Can it, be shown from the apostle’s own statements, that his whole future theology was already, contained in the Damascus experience,, embryonically or even already clearly, visible? Only the passages in which it is clear, that Paul is referring back to the Damascus, event can provide the textual basis: 1 Cor.

Page 87 :

9:1; 15:8; 2 Cor. 4:6; Gal. 1:12–16; Phil., 3:4b–11.[2] What stands out about these, texts is their almost stenographic brevity., Not only does Paul only rarely mention this, event, which turned his whole life around;[3], he reduces its content to the language of, visionary prophecy.[4], Paul’s Own Testimony to His Call, Paul speaks for the first time about his, Damascus experience in 1 Cor. 9:1. He does, not do this on his own initiative; it is clearly, the Corinthian dispute about his apostleship, that forces him to do so. In terms of text, pragmatics, 1 Cor. 9:1ff.[5] and 15:1ff.[6], must be read as Paul’s defense of his, apostleship (cf. 1 Cor. 9:2a; 15:9–10); this is, why they give information about the event on, which his apostleship is based. In 1 Cor. 9:1, Paul defends his legitimation as an apostle, above all by claiming that he had seen Ἰησοῦν, τὸν κύριον (Am I not free? Am I not an apostle?, Have I not seen Jesus our Lord?). In Corinth, his apostleship was disputed because, among, other reasons, he had never seen the Lord; it, is no longer clear whether his opponents

Page 88 :

referred to the earthly or resurrected Jesus., [7] Paul connects his claim to have “seen”, Jesus with the risen Lord, giving the content, of the Damascus experience as Ἰησοῦν τὸν, κύριον ἡµῶν ἑώρακα (I have seen Jesus our, Lord). Paul provides no information about, date and place; moreover, it remains unclear, whether the apostle saw the Lord in heaven, or on earth. In 1 Cor. 15:8 the apostle, includes himself in the series of witnesses to, the resurrection and derives his apostleship, from an appearance of the Lord that was, granted to him as it was to the others, mentioned (Last of all, as to one untimely, born, he appeared also to me). We see this in, the parallel uses of ὁράω (see) in 15:5, 7, and, 8 and in the way 15:8 is connected to the, rest of the paragraph. The altered, perspective and linguistic formulation in, contrast to 1 Cor. 9:1 probably reflects 1, Cor. 15:3–5 and its background in the, tradition.[8] It is to Paul as the least of all the, apostles that Christ has appeared, which, means that here also, as in 1 Cor. 9:1, the, ὁράω must have an exclusively, christologicalsoteriological meaning. Both 1, Cor. 9:1 and 15:8 manifest a firm connection

Page 89 :

between vision/appearance and election to, apostleship; that is, his call serves as Paul’s, proof of his (theological and financial), independence.[9], Galatians 1:12–16 points in the same, direction: In response to the attacks on his, gospel and his apostleship, Paul objects in, Gal. 1:12 that he did not receive his gospel, from any human being ἀλλὰ δι᾽ ἀποκαλύψεως, Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ (but through a revelation of, Jesus Christ).[10] On the basis of 1:16a, “to, reveal his Son to me,” this “revelation of, Jesus Christ” is to be construed as an, objective genitive, that is, “a revelation about, [not ‘from’] Jesus Christ.”[11] This revelation, impelled Paul to break with his splendid past, as a Jew and persecutor of the church of, God. In 1:15–16 Paul describes his call,, installation into office, and commissioning as, a preacher of the gospel: “But when God,, who had set me apart before I was born and, called me through his grace, was pleased to, reveal his Son to me, so that I might, proclaim him among the Gentiles. . . .”, Echoes of the call stories of Old Testament, prophets are clearly recognizable (compare, 1:15b with Jer. 1:5; Isa. 49:1, 5; Gal. 1:16b

Page 90 :

with Isa. 49:6);[12] it is even possible that, Paul here takes up a stereotyped schema of, prophetic calls based on the Old Testament., [13] Paul clearly understands his call,, installation, and commissioning in analogy to, the great prophets of the Old Testament,, with a particularly close connection to, Deutero-Isaiah (cf. Isa. 49:1–6).[14] Paul is, now to fulfill the proclamation—announced, in the Old Testament but not yet carried out, —of the saving will of God that includes the, Gentiles. As apostle of Jesus Christ and, proclaimer of the gospel to the Gentiles, Paul, understands himself to be a prophet called, by God.[15] Like Amos and Jeremiah (cf., Amos 3:8; Jer. 20:9), his whole life stands, under the compulsion to proclaim the, message he has received from God (cf. 1 Cor., 9:16). As the Servant of the Lord in DeuteroIsaiah was separated from his mother’s, womb and dedicated to the task of bringing, light to the Gentiles (cf. Isa. 49:1, 6), so Paul, sees himself as called by God to be the, apostle to the Gentiles (cf. Gal. 1:16; Rom., 1:1ff.). In Gal. 1:15a εὐδόκησεν (it pleased, [God]) emphasizes the soteriological, dimension of the event for the person of

Page 91 :

Paul, and God’s separating him for the, ministry of preaching the gospel among the, Gentiles emphasizes the universal aspect of, this event. Galatians 1:16a, where ἐν ἐµοί (in, me) is to be translated as the simple dative,, refers to the event of the call itself.[16] The, content of the revelation granted to Paul is, restricted to the reality of Jesus as the “Son, of God,”[17] which suggests an exclusively, christologicalsoteriological interpretation of, the Damascus event.[18] Paul describes, neither his call nor commissioning in the, usual terminology of justification that he, employs elsewhere in his polemical, argumentation in Galatians, which one would, expect if the origin of the Pauline critique of, the Torah had already been present in his, Damascus experience. According to the, testimony of the Galatian letter, we should, not interpret the Damascus event in the, categories of law/Torah versus Christ; its, scope is limited to the revelation of the, identity of Christ as such, which forms the, basis for Paul’s call and commissioning., Whether there is a reference to the, Damascus event in 2 Cor. 4:6 is a disputed, point: “For it is the God who said, ‘Let light

Page 92 :

shine out of darkness,’ who has shone in our, hearts to give the light of the knowledge of, the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ.”, The plural formulation ἐν ταῖς καρδίαις ἡµῶν (in, our hearts) could indicate that Paul is not, referring to a particular event but to what is, typical for the preacher of the gospel and all, believers. The light that illuminates the, believer comes from God, who has already, revealed his light at creation.[19] To be sure,, in 2 Corinthians Paul often uses the plural, when speaking of himself (compare, e.g.,, 2:12 with 2:15; 3:1; 4:1 and passim)., Moreover, 2 Cor. 7:3 shows clearly that the, expression “in our hearts” can stand for Paul, himself. The following observations speak in, favor of a connection between 2 Cor. 4:6 and, the Damascus experience:[20] (1) The aorist, ἔλαµψεν refers to a particular event in the, past. (2) The light metaphor appears in, numerous Old Testament texts in the context, of calling and commissioning (cf. esp. Isa., 42:6 LXX: “I, the Lord God, have called you, . . . to be a light to the nations”; cf. also Isa., 42:16; 60:1–3). (3) As in Gal. 1:16, 2 Cor. 4:6, is concerned with an internal event, an inner, “seeing.” (4) The context of 2 Cor. 4:6 deals

Page 93 :

with the founding and essential nature of, Paul’s apostleship and his gospel. From the, viewpoint of the history of traditions, the, motif of the glory of the chosen one points to, a throne room vision (cf. Ezek. 1:26, 28; 1, En. 45:1–6; 49:1–4). At Damascus God, revealed his glory in the face of Jesus Christ., Thus Paul attained the insight that Christ, belongs to the realm of God’s throne. The, exalted one, as the εἰκὼν τοῦ θεοῦ (image/icon, of God, 2 Cor. 4:4), is the continuing bearer, of the divine δόξα (glory; cf. also 1 Cor. 2:8)., In Phil. 3:4b–11 Paul debates with Jewish, Christian opponents, holding up to them, as, the “gain” he once had, his own Jewish origin, and his activity as a persecutor. All this has, now for him become “loss” for the sake of, Christ (3:7). The purely, christologicalsoteriological dimension of the, Damascus event becomes completely visible, in 3:8, where Paul describes it as τῆς γνώσεως, Χριστοῦ Ἰησοῦ τοῦ κυρίου µου (knowing Christ, Jesus my Lord). This expression is found only, here in Paul and has a very personal, character.[21] The knowledge of Christ, effects a radical new orientation through the, power of the present Lord. In 3:8–10 the

Page 94 :

doctrine of justification and ontological, teaching about redemption, juridical and, participatory ways of thinking, cannot be, separated from each other:[22] “I regard, everything as loss because of the surpassing, value of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord. For, his sake I have suffered the loss of all things,, and I regard them as rubbish, in order that I, may gain Christ and be found in him, not, having a righteousness of my own that comes, from the law, but one that comes through, faith in Christ, the righteousness from God, based on faith. I want to know Christ and the, power of his resurrection and the sharing of, his sufferings by becoming like him.” If, on, the one hand, Paul speaks of being found ἐν, αὐτῷ (in him), on the other hand, faith in, Jesus Christ appears as the effective basis of, his “own righteousness” (ἐμὴν δικαιοσύνην)., Grammatically, 3:9 is to be understood as a, parenthesis;[23] accordingly the passage in, Philippians 3, from late in Paul’s career,, supports the interpretation “that Paul did not, originally understand his call in the, categories of the doctrine of justification but, in a christological-ontological sense, as the, beginning point of his knowledge of Jesus

Page 95 :

Christ the Lord.”[24] Moreover, the abrupt, antithesis ἐκ νόμου / ἐκ θεοῦ (from the law /, from God) is obviously conditioned by the, situation in Philippi and may not be simply, projected back onto the Damascus event.[25], Gerd Theissen interprets Rom. 7:7–23 and, Phil. 3:4–6 from a psychological perspective,, as Paul’s working through his subconscious, conflict with the law: “The thesis defended, here . . . is that Phil. 3:4–6 reflects the, consciousness of the pre-Christian Paul,, while Romans 7 depicts a conflict that was, unconscious at the time, one of which Paul, became conscious only later.”[26] Gerd, Lüdemann argues similarly that Paul’s, subconscious “Christ complex” was “formally, brought to the boil by the Christians whom, he persecuted.” “He wanted to find release, by fighting an external enemy. That became, his ‘destiny.’ And Saul became Paul.”[27], Doubtless a call also includes psychological, dimensions,[28] but these can be understood, as reactions to the prior act of God. When, explanatory psychological models go beyond, this and claim to be able to explain in thisworldly terms not only the repercussions but, also the ultimate cause of the event, they

Page 96 :

confuse call with conversion, deny the, possibility of God’s acting in history, and, make absolute claims. The subjective, personal experience of the exegete is, projected beneath the text and presented as, “objective” knowledge. Moreover, the, psychological theories used for such, explanations have themselves recently been, subjected to massive criticism within the, field of psychology regarding both their, presuppositions and their practical, application (authoritarian self-preservation, mechanisms), raising questions about their, scientific validity.[29] The following holds, true for Paul: (1) Before the Damascus event, he was blameless with regard to the law; a, (conscious or subconscious) conflict with the, law cannot be inferred from the texts. (2) At, Damascus something happened to him at, God’s initiative, he saw the one who had, been crucified had been raised, and he, acknowledged the crucified Jesus of, Nazareth to be the Messiah. No, interpretation can get behind this statement, of recognition and faith; the experienced, reality of God can neither be confirmed nor, disproved by psychology or history. Paul

Page 97 :

understood the resurrection of Jesus, obviously as an authentic event sui generis,, not subject to historical demonstration as an, event in space and time., Paul never speaks voluntarily of the, Damascus event; he always brings up the, subject only when provoked by his, opponents. All the texts show that Damascus, is to be interpreted in, christologicalsoteriological terms and is, centered on the overwhelming revelation, that Jesus Christ belongs to the realm of God, and on the call of Paul to be an apostle.[30], From the Damascus event Paul derived his, right to belong to the circle of the original, Jerusalem disciples, a group firmly fixed in, history and bound to a particular place, even, though in fact he was a wandering apostle., [31] The legitimacy of his apostleship was, disputed throughout his life: he had not, known the historical Jesus, he appealed to a, prophetic revelation and call, he in fact, operated as a missionary scribal teacher, —“All in all, the exact opposite of what had, previously been understood as an, apostle.”[32]

Page 98 :

The Testimony of Acts, Three times Luke pictures the great turn in, the life of Paul that transformed him from, persecutor to preacher of the gospel (Acts, 9:3–19a; 22:6–16; 26:12–18),[33] thereby, signaling the epoch-making importance of, this event. It is likely that behind Acts 9:3–, 19a there lies an earlier legend about Paul,, current in the church of Damascus, which, told how Paul, the persecutor of Christians,, near Damascus had been brought to a new, realization of the identity of Jesus Christ and, how his traveling companions had brought, him to Damascus (cf. Acts 9:11).[34], Nonetheless, serious tensions between the, testimony of Acts and Paul’s own statements, cannot be overlooked: (1) According to 1, Cor. 9:1; 15:8, Paul himself understands the, Damascus event as an Easter Christophany,, of which there is nothing in Acts 9. For Luke,, the period of Easter appearances obviously, came to an end with Jesus’ ascension, so that, at Damascus Paul only saw a bright light and, heard a voice[35] but saw no face and, encountered no person. (2) The commission, to preach, which was for Paul constitutive of

Page 99 :

the Damascus event (cf. Gal. 1:16b), is, absent from Acts 9:3–19a and is only, appended in a modified form in Acts 9:20. (3), The fundamental connection between the, Damascus event and his apostleship, so, important for Paul, does not appear in Acts, 9.[36], But had not Paul persecuted parts of the, Christian community because of its critical, stance toward the Torah? Did he not first, become aware of the Christian message in, the form purportedly advocated by the, Stephen group, so that Paul’s own later, theology, with its critical stance toward the, Torah, must go all the way back to, Damascus? The answer to these questions, can only come from Acts 6:8–15, which, reports the appearance of Stephen on the, scene.[37] According to Acts 6:1–6[38] and, the summarizing note in 6:7,[39] the, charismatic leader Stephen emerges in 6:8, with hardly any transition. By placing him in, this context, Luke seems to number Stephen, among the “Hellenists,” though he is never, specifically identified as such.[40] Hellenistic, Jews emerge as Stephen’s opponents, but, they are not able to withstand him, a

Page 100 :

fulfillment of the promise of Luke 21:15.[41], Then men are instigated to make libelous, charges against Stephen. Here we should, note two things: (1) It is not the disputants, themselves who libel Stephen but men who, have not even heard him. (2) Luke explicitly, designates the charges as libel, showing he, considers them to be untrue.[42] In 6:13–14, false witnesses appear again, in a passage, that clearly represents Lukan redaction., They are the false witnesses whom Luke, leaves unmentioned at the trial of Jesus, (compare Mark 14:55–60 with Luke 22:66–, 67). Luke has also intentionally relocated the, purported saying of Jesus about the, destruction of the temple into this passage,, since here—as the testimony of false, witnesses, dissociated from Jesus—there is, no longer any need to tone it down or get, around it (cf. Mark 14:58; Matt. 26:61; John, 2:19).[43] The charge of attacking Mosaic, tradition goes back to texts such as Mark, 2:23ff.; 7:14; 10:5–6. Proceeding from this, basis in the tradition, Luke places the, statement in Acts 6:13b, that Stephen had, spoken against the temple and the, law/Torah, and the summary of 6:14 in the

Page 101 :

mouth of the false witnesses (not Stephen’s;, cf. also Acts 7:48–50). He composes 6:15 in, view of the following speech, also, anticipating the vision report in 7:55–56,, which manifests parallels to Luke’s portrayal, of Jesus’ transfiguration (cf. Acts 6:15/Luke, 9:29; Acts 7:55–56/Luke 9:32)., In summary, it may be said that in Acts, 6:8–15 Luke intentionally reworks material, from his tradition of the trial of Jesus in, order to present the trial of the first martyr, in this same light.[44] Here we also see an, additional Lukan interest: “According to, Luke, Stephen advocates the same basic, position that will later be adopted by Paul, (compare 6:13–14 and 7:48 with 21:21, 28;, 7:58 with 9:29).”[45] Especially the, redactional agreements between Acts 6:13, and 21:28[46] indicate that Acts 6:13, represents the Lukan view of the event, not, an old, historically reliable tradition. It is, obvious that by drawing parallels between, Stephen and Paul, Luke wants to emphasize, the salvation-historical continuity in early, Christian theology and mission. The, generally redactional character[47] of Acts, 6:8–15 and the inconsistencies in its content

Page 102 :

mean we cannot consider it a reliable, historical report of the theology of Stephen, or the “Hellenists.”, It is not demonstrable that the narrative of, Stephen and the “Hellenists” represents a, stance more critical of the Torah than what, would have been possible in Judaism at the, beginning of the Christian era, a position, that would have justified persecution. Thus, we must consider improbable the claim that, they were driven out of Jerusalem because of, this anti-Torah stance, and it is unlikely that, Paul received his own Torah-critical attitude, standpoint from them.[48] The better view is, that what led to persecution of the new, movement, including Paul’s own activity as a, persecutor, was the proclamation of the, crucified Jesus of Nazareth as the Messiah of, Israel, in connection with the movement’s, critical view of the temple[49] and the, growing independence of its organizational, structure and missionary practice.[50], 4.2 Significance of the Damascus, Event

Page 103 :

Several interpreters have regarded, Damascus as the origin of the whole of Paul’s, theology, especially of his doctrine of, justification. They identify his new decision, regarding Christ with a new decision, regarding the Torah,[51] and Rom. 10:4 then, describes the content of the Damascus event., [52] By attributing Pauline theology to the, Damascus experience and seeing it as, nothing else than the explication of this, event, they can consider its unity a proven, fact. They then see all changes as, developments of this primal event or as, applications of it, conditioned by particular, situations. Paul’s own statements, however,, do not support the claim for such sweeping, implications. Paul never mentions any, biographical details of the event at, Damascus; he stamps his presentation with, standard expressions and refers strictly to, his new knowledge of Jesus Christ and the, founding of his apostleship. In Paul’s own, writings there are no terms or concepts for, the interpretation of the Damascus event,, and in no passage where he is developing his, theology does he appeal to Damascus.

Page 104 :

The New Knowledge, It is clear from the apostle’s own, statements that we must understand, Damascus as a gracious act of God that, granted Paul new knowledge on four, fundamental points:[53], (1) Theological knowledge: God again, speaks and acts; at the end of the age God, reveals his saving act in a new way. Through, God’s intervention, completely new, perspectives are opened up in and for, history., (2) Christological knowledge: The crucified, and risen Jesus of Nazareth now belongs, forever at God’s side; he is God’s, representative who takes his place in heaven, as the “second power.”[54] As “Lord” (1 Cor., 1:9, κύριος), “the Anointed One” (1 Cor. 15:3,, Χριστός [Christ, Messiah]), “Son” (Gal. 1:16,, υἱός) and “image of God” (2 Cor. 4:4, εἰκὼν τοῦ, Θεοῦ), Jesus Christ is the permanent mediator, of God’s power and revelation. His exaltation, and proximity to God reveal the honor of his, unique office., (3) Soteriological knowledge: In the, present, the exalted Christ already grants

Page 105 :

believers participation in his reign. They are, already incorporated within a process of, universal transformation that began with, Christ’s resurrection, continues in the power, of the Spirit, and will soon move to its, climactic conclusion at the parousia and, judgment., (4) The biographical dimension: God has, elected Paul and called him to announce this, unheard-of good news to the nations. Paul, himself thus becomes an integral element in, God’s plan of salvation, for he is the one, through whom the gospel must be delivered, to the world in order to save those who, believe., The texts have only a minimum to say, about the way in which this new knowledge, came to Paul. The Damascus experience no, doubt had both external (cf. 1 Cor. 9:1; 15:8), and internal (Gal. 1:16; 2 Cor. 4:6), dimensions, possibly including an audition, (cf. καλέω [call] in Gal. 1:15). But any, additional interpretation of the content or of, the psychology involved is lacking in Paul, so, that we should draw no further conclusions, beyond what these texts themselves say.[55]

Page 106 :

The Consequences, If the contents of the Damascus event were, Christophany and induction into office,, apostolic call and commissioning,[56] so that, from Paul’s own point of view his recognition, that Jesus Christ belongs to the category of, deity and his concept of apostleship give the, key to understanding the Damascus event,, then we cannot simply equate the, significance of the Damascus event with the, doctrine of justification found in the Galatian, and Roman letters, written decades later, or, with Pauline theology as a whole. There can, be no dispute, however, that Damascus must, have had an effect on the Pauline, understanding of the law/Torah and, justification and on Paul’s thought as a, whole.[57] But every reconstruction that, goes beyond Paul’s own statements is, misguided, for such reconstructions, represent a later stage of Pauline theology, when Paul’s whole line of argument had been, conditioned by later situations, a theology, that cannot simply be traced back point by, point to the Damascus experience.[58] First, Thessalonians and the Corinthian

Page 107 :

correspondence, in which νόµος (law) either is, entirely absent or does not appear in the, reflective sense found in the Galatian and, Roman letters, confirm this understanding of, the Damascus event. And the considerable, tensions between the ways the law is, understood even in Galatians and, Romans[59] indicate that there can be no, talk of a unified doctrine of the law already, conveyed at Damascus.[60] Granted, the, radical turn in the course of Paul’s life at, Damascus and the fundamentally new, orientation could not, in the long run, remain, without consequences for the former, Pharisee Paul, but a point-for-point, identification of Paul’s new knowledge of, Christ at Damascus with his critique of the, law cannot be found in the Pauline texts.[61], Paul certainly had already thought about the, significance of the law/Torah for Gentile and, Jewish Christians before his composition of, the letters to the Galatians and Romans.[62], But whether he had always thought about, this in the categories found in Galatians and, Romans must remain an open question. The, subject matter of justification and law had, always been present with Paul since his

Page 108 :

conversion, but not the doctrine of, justification and law as found in Galatians, and Romans., Damascus as Experience of, Transcendence, When understood in this way, the, significance of the Damascus event for, Pauline theology is by no means belittled. On, the contrary, the overwhelming experience, of the risen Jesus Christ determined the life, of the apostle from that point forward,, without being reducible to statements of, theological doctrine. At the beginning of, every foundational religious experience, stands the sense of being grasped, the, experience of participation, but not, systematic analysis. Damascus is an external, experience of transcendence[63] that lays, the foundations for a new identity. The, concept of identity is particularly appropriate, as a means of grasping the content of the, Damascus experience and its consequences., [64] God acts to open new horizons for Paul:, human judgment on the crucified Jesus was, nullified; Jesus had not died on the cross as

Page 109 :

one under God’s curse, but he belongs at, God’s side, he is God’s representative, the, bearer of God’s glory who continues forever., Paul experiences Damascus as the, intersection of two worlds—the Son of God, appears to him in the world of space and, time. Seeing the risen one leads Paul to, surrender his former “I,” a “divesting of, self”[65] that is the negative presupposition, for the new being in Christ. Paul is given the, knowledge that with the resurrection of, Jesus Christ from the dead, God has opened, up the decisive epoch of salvation history, an, epoch in which Paul himself is incorporated, as preacher of this gospel.[66] Paul, experienced Damascus as participation in the, Christ event, which gave him a new identity, and at the same time compelled him to, restructure his picture of himself and the, world. God granted him a new knowledge of, the person of Jesus Christ and gave him a, new assignment: to proclaim the gospel of, Jesus Christ to the Gentiles.[67] Paul, understood his apostolic office on the basis, of this event. Paul did also take up elements, from his former symbolic universe into his, new identity, but in this process they were

Page 110 :

reevaluated within the new system of, coordinates.[68] From the perspective of, temporal theory, identity is necessarily a, process of constant reformation;[69] from, the viewpoint of identity theory, we must, also regard it as improbable that at, Damascus Paul already had at his disposal all, the elements in his later symbolic universe as, represented in Galatians and Romans., Nonetheless, Damascus is undoubtedly the, fundamental point of departure for Pauline, meaning formation. Whereas he could, formerly understand the proclamation of the, crucified Messiah only as provocation, the, Damascus experience led him to the insight, that the cross was filled with the inherent, potential for unexpected meaning. Paul now, combines biographical thinking with, universal perspectives, for he stands before, the task of taking his experience and, interpretation of a past event that happened, to one individual and erecting a meaning, structure that provides orientation in the, present and hope for the future.[70] A mere, historical fact such as the crucifixion is not in, itself a bearer of meaning; it requires an, additional constructive procedure in order to

Page 111 :

“clothe facts with meaning and significance,, to create from the chaos of meaningless, factuality a cosmos of meaningful and, significant history.”[71] From the religious, certainty of the Damascus event, Paul sets in, motion a process of universalistic meaning, formation that was to have unparalleled, effects, making it possible for all people to, understand their own existence within the, whole scheme of things. He constructs and, presents a network of meaning that relates, one’s individual existence to its social, obligations, and binds together one’s secure, everyday world and crucial experiences with, transcendent reality.

Page 112 :

6, The Apostolic Council and the, Incident at Antioch The Problems, Remain Unresolved, Some events promise clarification and, resolution but in fact are only the occasion, for new conflicts. Agreements can be, understood differently by the parties, involved; when viewed in a later perspective,, many things do not look the same as they, originally did., 6.1 The Apostolic Council After, completing their mission in Syria, and parts of Asia Minor, Barnabas, and Paul returned to Antioch.[1], Here “certain individuals” came, down from Judea who “were, teaching the brothers, ‘Unless you, are circumcised according to the, custom of Moses, you cannot be, saved’” (Acts 15:1). This resulted, in a fierce debate between the

Page 113 :

strict Jewish Christians on the one, side and Barnabas and Paul on the, other. The Antioch congregation, then decided to send Paul,, Barnabas, and some other, coworkers to Jerusalem to resolve, the issue in discussion with the, earliest church (cf. Acts 15:2; Gal., 2:1). Paul himself in Gal. 2:2a, gives a somewhat different picture, of the concrete occasion of the, Jerusalem trip: “I went up in, response to a revelation.”[2] He, thus no longer represents his, presence at the apostolic council, within the framework of the, mission program of the Antioch, church. One can suppose that it is, the Lukan view of history that, causes Luke to place the, connection of Barnabas and Paul, to the Antioch church in the, foreground at the apostolic, council. On the other hand, Paul, himself also formulates his own, portrayal tendentiously, for he, wants to emphasize his

Page 114 :

independence from Jerusalem and, the other churches. Furthermore,, he discloses his own, understanding of why he, participated in the apostolic, council: µή πως εἰς κενὸν τρέχω ἢ ἔδραµον, (in order to make sure that I was, not running, or had not run, in, vain, Gal. 2:2). Torah-observant, Jewish Christians had intervened, in the congregations founded by, the apostle, took note of their, freedom (from the Torah), and, come to the apostolic council to, insist that Gentile Christians be, circumcised (Gal. 2:4–5).[3] Paul, had been conducting a mission to, the Gentiles in which circumcision, was not required to become, Christians (which strict Jewish, Christians then saw as in fact, Torah-free).[4] Paul was obviously, afraid that the agitation of these, opponents would influence the, Jerusalem leaders to reject his, mission and thus cause it to be, nullified. This would mean that his

Page 115 :

apostolic commission to found, churches could not be carried out, (cf. 1 Thess. 2:19; 1 Cor. 9:15–, 18:23; 2 Cor. 1:14). Even more, drastic: the apostle saw that if he, were to fail in the task to which he, alone had been commissioned, his, glory on the day of Christ, his, eschatological salvation, was in, danger (cf. Phil. 2:16).[5], The apostolic council is also indirectly a, result of significant changes in the history of, the early Jerusalem church. In the, circumstances related to Agrippa I’s, persecution in 42 CE, James the son of, Zebedee was killed (Acts 12:2) and Peter, gave up the leadership of the Jerusalem, church and left the city (Acts 12:17). It is, clear that James the Lord’s brother (cf. Mark, 6:3) took over Peter’s position, as indicated, by a comparison of Gal. 1:18–19 with Gal. 2:9, and 1 Cor. 15:5 with 1 Cor. 15:7 and by the, last words of Peter in Acts 12:17b (“Tell this, to James and to the [Jerusalem] believers”), and the picture of the church in Acts 15:13;, 21:18.[6] Although Peter himself probably

Page 116 :

had a liberal stance on the question of, accepting uncircumcised Gentiles into the, new movement (cf. Acts 10:34–48; Gal. 2:11–, 12) and was later a sympathetic participant, in the Gentile mission (cf. 1 Cor. 1:12; 9:5),, we must see James and his group as, representatives of a strict Jewish Christianity, (cf. Gal. 2:12a) that consciously understood, itself as a part of Judaism and considered, Torah observance a requirement for, acceptance into the new movement.[7] James, adopted this position not only as a political, necessity but as a matter of conviction.[8] He, rejected table fellowship between Jewish, Christians and Gentile Christians (Gal. 2:12a), and was obviously highly respected by the, Pharisees. Josephus reports that after the, martyrdom of James in the year 62 CE, the, Pharisees bitterly demanded the deposition, of Ananus, the high priest who was, responsible for James’s death.[9] Very likely, those who advocated the circumcision of, Gentile Christians felt that their demand was, strongly supported by the theological, position of James.

Page 117 :

The Issue The issue at the apostolic, council is clear: which criteria, must be fulfilled in order to belong, to the elect church of God and at, the same time maintain continuity, with the people of God of the first, covenant?[10] Should circumcision,, as the sign of God’s covenant (cf., Gen. 17:11) and thus of, membership in the elect people of, God, also be a general requirement, for Gentile Christians?[11] Must a, Gentile who wants to become a, Christian first become a Jew?, Since, from the Jewish perspective,, a person became a proselyte and, thus a member of the elect people, of God only by circumcision and, ritual immersion, it seemed clear, from the strict Jewish Christian, point of view that the new status, among the redeemed people of God, came only by baptism in the name, of Jesus Christ and by, circumcision.[12] The problem that, occupied the apostolic council (and, the conflict at Antioch) thus

Page 118 :

emerged in a time when the, definition of what Christianity, required on the ritual and social, level had not been fully decided., Neither the Christian identity, markers nor the lifestyle that this, implied had yet been clarified., Could Gentile Christian churches, be recognized as belonging to the, same church as Jewish Christians,, who for the most part still, participated in the life of the, synagogue? Previous Jewish selfunderstanding had considered it, fundamental that one’s nationalcultural community and one’s, religious community were one and, the same—must this now be given, up? Does maintaining the codes of, holiness and ritual purity matter?, How do believers in Jesus come to, participate in the people of God,, and how do the promises of God’s, covenant with Israel come to apply, to them? To what extent should the, markers of Jewish identity such as, circumcision, table fellowship only

Page 119 :

with one’s own people, and Sabbath, observance also apply to the, emerging Gentile churches? Does, the fundamental change of status, that has already occurred when one, professes Christian faith entail, additional changes in one’s status, that must be worked out? Are, baptism and circumcision, obligatory initiation rites for all, believers in Christ, or does baptism, alone make possible full, acceptance into the people of God?, The successful mission work of the, Antioch church generated these, issues,[13] especially the mission, of Barnabas and Paul among the, Gentiles (cf. Gal. 2:2c). But the, Gentile mission of the Antioch, church was not the only one in, early Christianity, as shown by the, founding of the Roman church and, the appearance of Apollos of, Alexandria in Corinth (cf. 1 Cor., 3:4ff.; Acts 18:24–28).

Page 120 :

The difficulty of finding a solution to this, problem was intensified by the fact that the, Torah contains no clear statements about, Jews (or Jewish Christians) and Gentiles (or, Gentile Christians) living together outside, the land of Israel. The young churches, composed of Jewish and Gentile Christians, were an entity sui generis; the Torah had not, foreseen such a situation and made no, provisions for it.[14] As instruction for Israel,, the Torah had no validity for Gentiles (cf., Exod. 34:10–17; Lev. 20:2–7). No text in it, calls for Gentiles to keep the command of, circumcision or Sabbath, since it was, acknowledged that Yahweh had assigned the, gods of other peoples to them (cf. Deut., 4:19). The solution attempted by the, apostolic decree regulated the relations, between Jewish Christians and Gentile, Christians in a manner analogous to those, between Israel and foreigners living in the, land, but this could not be a permanent, solution. The commands regarding resident, aliens (cf. Lev. 17–18, and esp. Exod. 12:43–, 49; 20:10; 23:12; Lev. 16:29; 20:2; 22:18–20;, 24:10–22; Num. 9:14; 15:30; 19:1–11) do not, facilitate their living together on an equal

Page 121 :

basis but throughout have an overtone of, subordination., What Happened at the Council?, We can reconstruct the basic outline of the, course of events at the apostolic council from, Acts 15:1–34 and Gal. 2:1–10,[15] even, though the two reports have variations in, details: (1) Paul and Barnabas came to, Jerusalem as authorized delegates of the, Antioch church (Acts 15:2, 4; Gal. 2:1, 9). (2), The agenda of the conference was the, fundamental justification for the Gentile, mission, and the practical procedures for, carrying it out (Acts 15:12/Gal. 2:2, 9). (3) At, the conference one group insisted on the, circumcision of Gentile converts (Gal. 2:4–5,, “false brethren”; Acts 15:5, Christian, Pharisees). (4) The conference proceeded on, two levels: a plenary meeting of the whole, church (Acts 15:12/Gal. 2:2a) and discussions, within a smaller circle (Acts 15:6, apostles, and elders; Gal. 2:9, the “pillars”). Paul’s, account of the council reflects this division of, responsibilities, for Gal. 2:3–5 reports the, events of the plenary session and Gal. 2:6–10

Page 122 :

refers to the agreement with the leadership, of the Jerusalem church. (5) According to, both reports, the council recognized the, Gentile mission that did not require, circumcision (Acts 15:10–12, 19/Gal. 2:9)., The Lukan presentation does deviate sharply, from Paul’s own account. According to Luke,, the Jerusalem church bound its basic, approval of the Gentile mission to the, condition that Gentiles observe a minimum of, ritual prescriptions (Acts 15:19–21, 28–29;, 21:25)—abstinence from idol worship, meat, from animals that have been strangled,, blood, and sexual immorality. These four, abstinence prescriptions are oriented to the, prescriptions for Jews and resident aliens in, Lev. 17–18 and were understood as a model, for how Jewish Christians and Gentile, Christians could participate together in the, same congregations.[16] Luke also fails to, mention the dispute about the Gentile, Christian Titus (Gal. 2:3) and postpones the, agreement about the collection (Gal. 2:10; cf., Acts 11:27–30). Furthermore, in Luke’s, portrayal of the apostolic council, Paul plays, only a minor role, for it is Peter (Acts 15:7–

Page 123 :

11) and James (Acts 15:13–21) who make the, real decisions., The matter is portrayed differently in Gal., 2:1–10, where the real decision takes place, in the discussion between Paul on the one, side and James, Peter, and John on the other., Whereas Acts 15:5ff. recounts a discursive, explanation of the problem, Paul’s own, account contains no indication that the, content of his gospel received by revelation, was a matter for debate. He emphasizes,, rather, that the Jerusalem authorities, acknowledged his gospel qualitatively, in, terms of a theology of revelation (καὶ γνόντες, τὴν χάριν τὴν δοθεῖσάν µοι [recognizing the grace, that had been given to me], Gal. 2:9),[17] so, that the basis of the accord they sought was, given in a revelation to Paul. According to, Paul, this agreement included an, ethnographic division of the world mission:, “agreeing that we should go to the Gentiles, and they to the circumcised” (Gal. 2:9c). But, did this arrangement in fact result in the, unity of the people of God?, The Gospel of Uncircumcision and, the Gospel of Circumcision Are the

Page 124 :

Pauline εὐαγγέλιον τῆς ἀκροβυστίας, (gospel of uncircumcision) and the, Petrine εὐαγγέλιον τῆς περιτοµῆς (gospel, of circumcision) actually congruent, in terms of their content? On the, basis of Gal. 2:8–9c (εἰς τὰ ἔθνη . . . εἰς, τὴν περιτοµήν [to the Gentiles . . . to, the circumcised]), the genitive case, of τῆς ἀκροβυστίας and τῆς περιτοµῆς are, to be understood as “the gospel for, the uncircumcised . . . the gospel, for the circumcised.” At first the, contents of these two formulations, seem to manifest great agreement:, both sides certainly understand the, nucleus of the gospel as it is, transmitted in, for example, 1 Cor., 15:3b–5: “that Christ died for our, sins in accordance with the, scriptures, and that he was buried,, and that he was raised on the third, day in accordance with the, scriptures, and that he appeared to, Cephas, then to the twelve.”, Furthermore, the typical marks of, Jewish identity, such as, monotheism and numerous ethical

Page 125 :

admonitions, were not disputed., After all, everyone concerned, presupposed that salvation for, those who believed in Jesus was, attained only in continuity with, Israel., At the same time, the difference between, these two formulae may not be passed over, too lightly, for Paul usually speaks of the, “gospel of Christ” (on εὐαγγέλιον τοῦ Χριστοῦ, cf., Gal. 1:7 and also 1:6, 11, 12) or the “gospel, of God” (εὐαγγέλιον θεοῦ).[18] These two, formulae probably reflect the wording to, which those engaged in the apostolic council, had agreed.[19] Distinctive details in, language and content point to the traditional, character of Gal. 2:7–8: (1) only here do we, have “Peter and Paul” as a contrasting pair;, in Gal. 2:9 Paul returns to his normal usage, of the name Cephas; (2) the terms εὐαγγέλιον, τῆς ἀκροβυστίας and εὐαγγέλιον τῆς περιτοµῆς, appear only in Gal. 2:7 in Paul, and they are, not found elsewhere in the whole literature, of antiquity; and (3) stylistically, Gal. 2:7–8 is, a parenthesis (ὅτι πεπίστευµαι . . . εἰς τὰ ἔθνη [that, I had been entrusted . . . to the Gentiles]).

Page 126 :

The decisive difference in their content, certainly lay in the way circumcision was, evaluated in terms of salvation history and, the extent of Torah observance to be inferred, from this. Circumcision was by no means to, be considered an adiaphoron (matter of, indifference), for it was the entrance gate to, the whole law (cf. Philo, Spec. Laws 1.1ff.). It, documents Israel’s special status among the, nations, was a guarantee of this identity (cf., Jub. 15:25–34),[20] and at the same time, separated Israel from all other peoples (cf., Josephus, Ant 1.192; Tacitus, Hist. 5.5.2). For, strict Jewish Christians, there was a natural, connection between faith in the Messiah, Jesus of Nazareth, circumcision as a mark of, belonging to God’s chosen people, and, of, course, observance of the Torah. For them,, baptism did not take the place of, circumcision, and salvation did not occur as, something that transcended the law. The, incident at Antioch, the position of Pharisees, who had come to faith in Christ (Acts 15:1,, 5), and the demand made in Galatia and, Philippi that Gentile Christians be, circumcised point in this direction.[21] In, contrast, Paul can point to the obvious work

Page 127 :

among the Gentiles by God who shows no, partiality (Gal. 2:6).[22] By baptism and, reception of the Spirit, Gentile Christians are, already full and equal members in the people, of God (cf. Gal. 3:1–5, 26–28; Acts 10:44–48),, and so any additional legitimizing signs, would put in question God’s previous saving, acts among the Gentiles. Thus James,, Cephas, and John acknowledge the grace, conferred on Paul (Gal. 2:9a), and for his, part, he accepts both the responsibility for, the collection (Gal. 2:10) and the “gospel to, the circumcision.” We can no longer, determine with certainty whether the, singular formulation in Gal. 2:7 was coined, at the apostolic council or whether it goes, back to Paul himself. The decisive factor for, interpretation, however, continues to be the, realization that εὐαγγέλιον τῆς ἀκροβυστίας and, εὐαγγέλιον τῆς περιτοµῆς are not simply identical,, that this singular contrast does not deal with, the “one” Pauline gospel.[23] This is, indicated in no small way by the expression, φοβούµενος τοὺς ἐκ περιτοµῆς (for fear of the, circumcision faction) in Gal. 2:12. “Certain, people from James” demand that the “gospel, for the circumcision” be maintained, and

Page 128 :

charge Peter with violating its identity, markers., The Interpretations At the, apostolic council, both sides, recognized that the one God calls, people through the gospel in more, than one way and that believers, serve the will of God in different, ways.[24] Although differing, concepts of mission were advocated, at the apostolic council, the council, did not unite these into a single, view but acknowledged each as a, legitimate expression of Christian, faith. It was the equal status, not, the identity, of each version of the, gospel that was confirmed at the, apostolic council.[25] For Paul, this, was already clear, for he was the, real innovator; before Paul and, during the time of his mission with, the Antioch church, the obvious, marks of belonging to the people of, God were circumcision, Torah, observance, and faith in Jesus of, Nazareth as the Messiah.

Page 129 :