Page 1 :

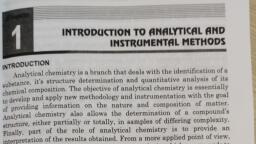

CHAPTER, ANALYTICAL OBJECTIVES, OR:, WHAT ANALYTICAL, CHEMISTS DO, Analytical chemistry is concerned with the chemical characterization of matter. Everything is made of, Chemicals make up everything we use or consume, and knowledge of the chem- chemicals. Analytical chem-, ical composition of many substances is important in our daily lives. Analytical, chemistry plays an important role in nearly all aspects of chemistry, for example,, agricultural, clinical, environmental, forensic, manufacturing, metallurgical, and, pharmaceutical chemistry. The nitrogen content of a fertilizer determines its, value. Foods must be analyzed for contaminants (e.g., pesticide residues) or, vitamin content. The air in cities must be analyzed for carbon monoxide. Blood, glucose must be monitored in diabetics (and, in fact, most diseases are diagnosed, by chemical analysis). The presence of trace elements from gun powder on a, murder defendant's hand will prove a gun was fired. The quality of manufactured, products often depends on proper chemical proportions, and measurement of the, constituents is a necessary part of quality control. The carbon content of steel will, determine its quality. The purity of drugs will determine their efficacy., ists determine what and, how much., 1.1 QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS, The discipline of analytical chemistry consists of qualitative analysis and quanti-, tative analysis. The former deals with the identification of elements, ions, or com-, pounds present in a sample (we may be interested in whether only a given sub-, stance is present), while the latter deals with the determination of how much of, one or more constituents is present. The sample may be solid, liquid, or gas. The, presence of gunpowder residue on a hand generally requires only qualitative, Qualitative analysis tells us, what chemicals are, present. Quantitative analy-, sis tells us how much., 1, 1/ 14

Page 2 :

CHAPTER 1/ANALYTICAL OBIECTIVES, OR: WHAT ANALYTICAL CHEMISTS DO, use of instrumentation. The formation of a white precipitate when adding a the, tion of silver nitrate to a dissolved sample indicates the presence of chlorid, the percent of sulfur impurity present., prints" of organic compounds or their functional groups., For quantitative analysis, a history of the sample composition will often be, known (it is known that blood contains glucose), or else the analyst will bave, performed a qualitative test prior to performing the more difficult quantitative, analysis. Modern chemical measurement systems often exhibit sufficient selee, tivity' that a quantitative measurement serves as a qualitative measurement, However, simple qualitative tests are usually more rapid than quantitative pro-, cedures. Qualitative analysis is composed of two fields: inorganic and organic., The former is usually covered in introductory chemistry courses, whereas the, latter is best left until after the student has had a course in organic chemistry., In comparing qualitative versus quantitative analysis, consider, for example,, the sequence of analytical procedures followed in testing for banned substances at, the Olympic Games. The list of prohibited substances includes about 500 different, active constituents: stimulants, steroids, beta-blockers, diuretics, narcotics, an-, algesics, local anesthetics, and sedatives. Some are detectable only as their me-, tabolites. Many athletes must be tested rapidly, and it is not practical to perform, a detailed quantitative analysis on each. There are three phases in the analysis: the, fast-screening phase, the identification phase, and possible quantification. In the, fast-screening phase, urine samples are rapidly tested for the presence of classes, of compounds that will differentiate them from "normal" samples. Various tech-, niques include immunoassays, gas chromatography, and liquid chromatography., About 5% of the samples may indicate the presence of unknown compounds that, may or may not be prohibited but need to be identified. Samples showing a, suspicious profile during the screening undergo a new preparation cycle (possible, hydrolysis, extraction, derivatization), depending on the nature of the compounds, that have been detected. The compounds are then identified using the highly, selective combination of gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS). In, this technique, complex mixtures are separated by gas chromatography and they, are then detected by mass spectrometry, which provides molecular structural data, on the compounds. The MS data, combined with the time of elution from the gas, chromatograph, provide a high probability of the presence of a given detected, compound. GC/MS is expensive and time consuming and so it is used only when, necessary. Following the identification phase, some compounds must be precisely, quantified since they may normally be present at low levels, e.g., from food,, pharmaceutical preparations, or endogenous steroids, and elevated levels must be, confirmed. This is done using quantitative techniques such as spectrophotometry, or gas chromatography., 'A clear distinction should be made between the terms specific and selective. A specific reaction or test, is one that occurs only with the substance of interest, while a selective reaction or test is one that can, occur with other substances but exhibits a degree of preference for the substance of interest. Few, reactions are specific but many exhibit selectivity., 2/ 14

Page 3 :

12 THE ANALYTICAL PROCESS, This text deals principally with quantitative analysis. In the consideration of, applications of different techniques, examples are drawn from the life sciences,, clinical chemistry, environmental chemistry, occupational health and safety ap-, plications, and industrial analysis., We describe briefly in this chapter the analytical process. More details are, provided in subsequent chapters., 1.2 THE ANALYTICAL PROCESS, A quantitative análysis involves several steps and procedures. The analytical process may, be defined as the following sequence of events: (1) defining the problem, (2) obtaining a, representative sample, (3) preparing the sample for analysis, (4) performing necessary, chemical separations, (5) performing the measurement, and (6) calculating the results and, presenting the data. The unit operations of analytical chemistry that are common to most, types of analyses are considered in more detail as follows., Defining the Problem, Before the analyst can design an analysis procedure, he or she must know what, information is needed, and what type of sample is to be analyzed. This will dictate, how the sample is to be obtained, how much is needed, how sensitive the method information needed., must be, how accurate and precise it must be, and what separations may be, required to eliminate interferences. The determination of trace constituents will, generally not have to be as precise as for major constituents, but greater care will, be required to eliminate trace contamination during the analysis., Once the required measurement is known, the analytical method to be used will, depend on a number of factors, including the analyst's skills and training in dif- analysis will depend on, ferent techniques and instruments; the facilities, equipment, and instruments, available; the sensitivity and precision required; the cost and the budget available; ment available, the cost,, and the time for analysis and how soon results are needed. There are often one or, more standard procedures available in reference books for the determination of an, analyte (constituent to be determined) in a given sample type. This does not mean, that the method will necessarily be applicable to other sample types. For example, stance analyzed for. Its, a standard Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) method for groundwater, samples may yield erroneous results when applied to the analysis of sewage, water. The chemical literature (journals) contains many specific descriptions of, analyses. Chemical Abstracts, published by the American Chemical Society, is a, good place to begin a literature search. It contains abstracts of all papers appear- good source of literature., ing in the major chemical journals of the world. Yearly and cumulative indices are, available, and many libraries have computer search facilities. The major analytical, The way an analysis is per-, formed depends on the, The way you perform an, your experience, the equip-, and the time involved., a., The analyte is the sub-, concentration is, determined., d, 1., Chemical Abstracts is a, y, st, Accuracy is the degree of agreement between a measured value and a true value. Precision is the, degree of agreement between replicate measurements of the same quantity and does not necessarily, Imply accuracy. These terms are discussed in more detail in Chapter 2., an, 3/ 14

Page 4 :

formed clinical and environmental analyses. The various techniques described in, Examples of the manner in which the analysis of particular types of samples are, chemistry journals may be consulted separately. Some of these are: Analytica, troscopy, Clinica Chimica Acta, Clinical Chemistry, Journal of the Association of, analyst can often use literature information on a given analyte to devise an ap, and Talanta. While the specific analysis of interest may not be described, the, CHAPTER 1I ANALYTICAL OBJECTIVES, OR: WHAT ANALYTICAL CHEMISTS, Chimica Acta, Analytical Chemistry, Analytical Letters, Analyst, Applied Spec-, Official Analytical Chemists, Journal of Chromatography, Spectrochimica Acta., and knowledge to develop an analytical method for a given sample. The literature, propriate analysis scheme, Finally, the analyst may have to rely upon experience, references in Appendix A describe various procedures for the analysis of different, made are given in Chapters 18 and 19. These chapters describe commonly per-, substances., this text are utilized for the specific analyses. Hence, it will be useful for v in, read through these applications chapters both now and after completing the, jority of this course to gain an appreciation of what goes into analyzine, samples and why the analyses are made., Once the problem has been defined, the following steps can be started., Obtaining a Representative Sample, A chemical analysis is usually performed on only a small portion of the material, to be characterized. If the amount of material is very small and it is not needed for, future use, then the entire sample may be used for analysis. The gunshot residue, on a hand may be an example. More often, though, the characterized material is, of value and must be altered as little as possible in sampling., The material to be sampled may be solid, liquid, or gas. It may be homogeneous, or heterogeneous in composition. In the former case, a simple "grab sample", taken at random will suffice for the analysis. In the latter, we may be interested in, the variation throughout the sample, in which case several individual samples will, be required. If the gross composition is needed, then special sampling techniques, will be required to obtain a representative sample. For example, in analyzing for, the average protein content of a shipment of grain, a small sample may be taken, from each bag, or tenth bag for a large shipment, and combined to obtain a gross, sample. Sampling is best done when the material is being moved, if it is large, in, order to gain access. The larger the particle size, the larger should be the gross, sample. The gross sample must be reduced in size to obtain a laboratory sample of, Analytical chemists analyze, olids, liquids, and gases., The gross sample consists, of several portions of the, material to be tested. The, laboratory sample is a small several grams, from which a few grams to milligrams will be taken to be analyzed, portion of this, made ho-, (analysis sample). The size reduction may require taking portions (e.g., two quar-, ters) and mixing, in several steps, as well as crushing and sieving to obtain a, uniform powder for analysis. Methods of sampling solids, liquids, and gases are, discussed in Chapter 22., In the case of biological fluids, the conditions under which the sample is col-, lected can be important, for example, whether a patient has just eaten. The com-, position of blood varies considerably before and after meals, and for many anal-, vses a sample is collected after the patient has fasted for a number of hours., Preservatives such as sodium fluoride for glucose preservation and anticoagulants, may be added to blood samples when they are collected; these may affect a, mogeneous. The analysis, sample is that actually ana-, lyzed. See Chapter 22 for, methods of sampling., particular analysis., 4/ 14

Page 5 :

5, 12 THE ANALYTICAL PROCESS, Blood samples may be analyzed as whole blood, or they may be separated to, yield plasma or serum according to the requirements of the particular analysis., Most commonly, the concentration of the substance external to the red cells (the, extracellular concentration) wilH be a significant indication of physiological con-, dition, and so serum or plasma is taken for analysis., If whole blood is collected and allowed to stand for several minutes, the soluble Serum is the fluid sepa, protein fibrinogen will be converted by a complex series of chemical reactions rated from clotted blood., (involving calcium ion) into the insoluble protein fibrin, which forms the basis of Plasma is the fluid sepa-, a gel, or clot. The red and white cells of the blood become caught in the meshes, of the fibrin network and contribute to the solidarity of the clot, although they are, not necessary for the clotting process. After the clot forms, it shrinks and serum, but contains fibrin-, squeezes out a straw-colored fluid, serum, which does not clot but remains fluid, indefinitely. The clotting process can be prevented by adding a small amount of an, anticoagulant, such as heparin or a citrate salt (i.e.., a calcium complexor). An, aliquot of the unclotted whole blood can be taken for analysis, or the red cells can, be centrifuged to the bottom, and the light pinkish-colored plasma remaining can, be analyzed. Plasma and serum are essentially identical in chemical composition,, the chief difference being that fibrinogen has been removed from the latter., Details of sampling other materials are available in reference books on specific, areas of analysis. See the references at the end of the chapter for some citations., Certain precautions should be taken in handling and storing samples to prevent Care must be taken not to, or minimize contamination, loss, decomposition, or matrix change. In general,, one must prevent contamination or alteration of the sample by (1) the container, sample, (2) the atmosphere, or (3) light., The sample may have to be protected from the atmosphere or from light. It may, be an alkaline substance, for example, which will react with carbon dioxide in the, air. Blood samples to be analyzed for CO, should be protected from the atmo-, sphere., The stability of the sample must be considered. Glucose, for example, is un-, stable, and a preservative such as sodium fluoride is added to blood samples. The, preservation must not, of course, interfere in the analysis. Proteins and enzymes, tend to denature on standing and should be analyzed without delay. Trace con-, stituents may be lost during storage by adsorption onto the container walls., Urine samples are unstable, and calcium phosphate precipitates out, entrap-, ping metal ions or other substances of interest. Precipitation can be prevented by, keeping the urine acidic (pH 4.5), usually by adding 1 or 2 mL glacial acetic acid, per 100-mL sample. Store under refrigeration. Urine, as well as whole blood,, serum, plasma, and tissue samples, can also be frozen for prolonged storage., Deproteinized blood samples are more stable than untreated samples., Corrosive gas samples will often react with the container. Sulfur dioxide, for, example, is troublesome. In automobile exhaust, SO, is also lost by dissolving in, condensed water vapor from the exhaust. In such cases, it is best to analyze the, gas by a stream process., rated from unclotted, blood. It is the same as, ogen, the clotting protein., alter or contaminate the, Preparing the Sample for Analysis, The first step in analyzing a sample is to measure the amount being analyzed (e.g., The first thing you must do, volume or weight of sample). This will be needed to calculate the percent com-, position from the amount of analyte found. The analytical sample size must be ple to be analyzed., is measure the size of sam-, 5/ 14