Page 1 :

MARK DISTRIBUTION, ATTENDANCE, ASSIGNMENT, CLASS TEST, MID TERM, TRIMESTER FINAL, TOTAL, , 10 marks, 10 marks, 10 marks, 20 marks, 50 marks, 100 marks

Page 2 :

DEFINITION, Mechanics is the oldest physical science that deals with, , both stationary and moving bodies under the influence of, forces., The branch of mechanics that deals with bodies at rest is, called statics, while the branch that deals with bodies in, motion is called dynamics., The subcategory fluid mechanics is defined as the science, that deals with the behavior of fluids at rest (fluid statics), or in motion (fluid dynamics), and the interaction of fluids, with solids or other fluids at the boundaries., The study of fluids at rest is called fluid statics., , 3

Page 3 :

DEFINITION, The study of fluids in motion, where pressure forces are, , not considered, is called fluid kinematics and if the, pressure forces are also considered for the fluids in, motion. that branch of science is called fluid dynamics., Fluid mechanics itself is also divided into several, categories., The study of the motion of fluids that are practically, incompressible (such as liquids, especially water, and, gases at low speeds) is usually referred to as, hydrodynamics., A subcategory of hydrodynamics is hydraulics, which, deals with liquid flows in pipes and open channels., 4

Page 4 :

DEFINITION, Gas dynamics deals with the flow of fluids that undergo, , significant density changes, such as the flow of gases, through nozzles at high speeds., The category aerodynamics deals with the flow of gases, (especially air) over bodies such as aircraft, rockets, and, automobiles at high or low speeds., Some other specialized categories such as meteorology,, oceanography, and hydrology deal with naturally, occurring flows., , 5

Page 5 :

WHAT IS A FLUID?, , A substance exists in three primary phases: solid, liquid,, , and gas. A substance in the liquid or gas phase is referred, to as a fluid., Distinction between a solid and a fluid is made on the basis, of the substance’s ability to resist an applied shear (or, tangential) stress that tends to change its shape., A solid can resist an applied shear stress by deforming,, whereas a fluid deforms continuously under the influence, of shear stress, no matter how small., , 6

Page 6 :

WHAT IS A FLUID?, In, , , , , , , , , 7, , a liquid, molecules can move, relative to each other, but the volume, remains relatively constant because of, the strong cohesive forces between the, molecules., As a result, a liquid takes the shape of, the container it is in, and it forms a, free surface in a larger container in a, gravitational field., A gas, on the other hand, expands until, it encounters the walls of the container, and fills the entire available space., This is because the gas molecules are, widely spaced, and the cohesive forces, between them are very small., Unlike liquids, gases cannot form a, free surface

Page 7 :

Differences between liquid and gases, Liquid, , 8, , Gases, , Difficult to compress and, often regarded as, incompressible, , Easily to compress – changes of, volume is large, cannot normally, be neglected and are related to, temperature, , Occupies a fixed volume, and will take the shape of, the container, , No fixed volume, it changes, volume to expand to fill the, containing vessels, , A free surface is formed if, the volume of container is, greater than the liquid., , Completely fill the vessel so that, no free surface is formed.

Page 8 :

APPLICATION AREAS OF FLUID MECHANICS, Mechanics of fluids is extremely important in many areas, , of engineering and science. Examples are:, Biomechanics, Blood flow through arteries and veins, Airflow in the lungs, Flow of cerebral fluid, Households, Piping systems for cold water, natural gas, and sewage, Piping, , 9, , and ducting network of heating and airconditioning systems, refrigerator, vacuum cleaner, dish washer,, washing, machine, water meter, natural gas meter, air conditioner,, radiator, etc., Meteorology and Ocean Engineering, Movements of air currents and water currents

Page 9 :

APPLICATION AREAS OF FLUID MECHANICS, Mechanical Engineering, Design of pumps, turbines, air-conditioning equipment,, , pollution-control equipment, etc., Design and analysis of aircraft, boats, submarines,, rockets, jet engines, wind turbines, biomedical devices,, the cooling of electronic components, and the, transportation of water, crude oil, and natural gas., Civil Engineering, , , , , , Transport of river sediments, Pollution of air and water, Design of piping systems, Flood control systems, Chemical Engineering, Design of chemical processing equipment, 10

Page 10 :

Application areas of Fluid Mechanics, Turbomachines: pump, turbine, fan, blower, propeller, etc., Military: Missile, aircraft, ship, underwater vehicle, dispersion, , , , , , , , 11, , of chemical agents, etc., Automobile: IC engine, air conditioning, fuel flow, external, aerodynamics, etc., Medicine: Heart assist device, artificial heart valve, Lab-on-aChip device, glucose monitor, controlled drug delivery, etc., Electronics: Convective cooling of generated heat., Energy: Combuster, burner, boiler, gas, hydro and wind, turbine, etc., Oil and Gas: Pipeline, pump, valve, offshore rig, oil spill, cleanup, etc., Almost everything in our world is either in contact with a fluid, or is itself a fluid.

Page 11 :

12, , Derivation of the Newton’s law of viscosity, When two layers of a fluid, a distance 'dy' apart move one over, , the other at different velocities say u and u+ du as shown in Fig., 1.1 , the viscosity together with relative velocity causes a shear, stress acting between the fluid layers:

Page 12 :

13, , The top layer causes a shear stress on the adjacent lower layer while, , the lower layer causes a shear stress on the adjacent top layer., This shear stress is proportional to the rate of change of velocity with, respect to y. It is denoted by symbol τ called Tau., Mathematically,, or, , = du, dy, where μ (called mu) is the constant of proportionality and is known, , as the coefficient of dynamic viscosity or only viscosity.

Page 13 :

PROPERTIES OF FLUIDS, Any characteristic of a system is called a property., , Some familiar properties are pressure P, temperature T, volume V,, , and mass m., Other less, familiar properties Include viscosity, thermal, conductivity, modulus of elasticity, Thermal Expansion coefficient,, electric resistivity, and even velocity and elevation., Properties are considered to be either intensive or extensive., Intensive properties are those that are independent of the mass, of a system, such as temperature, pressure, and density., Extensive properties are those whose values depend on the size—, or extent—of the system. Total mass, total volume V, and total, momentum are some examples of extensive properties., , 14

Page 14 :

An easy way to determine, , whether, a, property, is, intensive or extensive is to, divide the system into two, equal parts with an imaginary, partition., Each part will have the same, , value of intensive properties, as the original system, but half, the value of the extensive, properties., , 15

Page 15 :

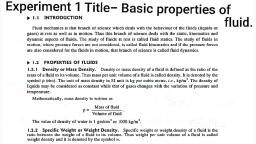

Density or Mass Density, Density or mass density of a fluid is defined as the ratio of the mass, , of a f1uid to its volume., Thus mass per unit volume of a fluid is, called density. It is denoted the symbol ρ (rho). The unit of mass, density in SI unit is kg per cubic meter, i.e ., kg/m3., The density of liquids may be considered as constant while that of, , gases changes with the variation of pressure and temperature., Mathematically mass density is written as., , =, , Mass of fluid, Volume of fluid, , The value of density of water is 1 gm/cm3 or 1000 kg/m3., , 16

Page 16 :

Factors affecting Density or Mass Density, The density of a substance, in general, depends on temperature, , and pressure., The density of most gases is proportional to pressure and inversely, proportional to temperature., Liquids and solids, on the other hand, are essentially, incompressible substances, and the variation of their density with, pressure is usually negligible., , Viscosity, Viscosity is defined as the property of a fluid which offers, , resistance to the movement of one layer of fluid over another, adjacent layer of the fluid., , 17

Page 17 :

Cohesion, Cohesion is the property of a fluid by which molecules of the same, liquid are attracted. This property enables the liquids to resist tensile, stress., , Adhesion, Adhesion is a property of a fluid by which molecules of different, liquids are attracted to each other or molecules of a liquid are, attracted to another body. This enables the two different liquids to, adhere to each other or to a liquid to adhere to another body., , Surface tension, The surface tension is the property of a liquid which enables it to, resist tensile stress. At the interface between a liquid and a gas, a film, or special layer seems to form on the liquid which is capable of, resisting a small tensile stress.

Page 18 :

19, , Specific weight or Weight Density, Specific weight or weight density of a fluid is the ratio, , between the weight of a fluid to its volume., Thus weight per unit volume of a fluid is called weight, density and it is denoted by the symbol w., Mathematically,, Weight of fluid (Mass of fluid) x Acceleration due to gravity, =, Volume of fluid, Volume of fluid, = Mass of fluid x g, Volume of fluid, =x g, w=, , w = g

Page 19 :

Specific Volume, Specific volume of a fluid is defined as the volume of a fluid, , occupied by a unit mass or volume per unit mass of a fluid is called, specific volume., Mathematically, it is expressed as, Specific volume =, , 1, 1, Volume offluid, =, =, Mass of fluid , Mass of fluid, Volume, , Thus specific volume is the reciprocal of mass density. It is, , expressed as m3/kg., It is commonly applied to gases., , 20

Page 20 :

Specific Gravity., , , Specific gravity is defined as the ratio of the weight density (or, density) of a fluid to the weight density (or density) of a standard, fluid., , , , For liquids, the standard fluid is taken water and for gases, the standard, fluid is taken air. Specific gravity is also called relative density. It is, dimensionless quantity and is denoted by the symbol S., Weight density (density) of liquid, Weight density (density) of water, Weight density (density) of gas, S(for gases) =, Weight density (density) of air, Thus weight density of a liquid = S x Weight densityof water, = S x 1000x 9.81N/m3, Thus density of a liquid = S x Densityof water, S(for liquids) =, , 32, , = S x 1000kg/m3

Page 21 :

Specific Gravity, If the specific gravity of a fluid, , is known, then the density of, the fluid will be equal to, specific gravity of fluid, multiplied by the density of, water., For example the specific, gravity of mercury is 13.6,, hence density of mercury, = 13.6 x 1000 = 13600, kg/m3., , 22

Page 22 :

Example 1., Calculate the specific weight, density and specific gravity of one, liter of a liquid which weighs 7 N., , 23

Page 23 :

Example 2. Calculate the density, specific weight and weight of one, liter of petrol of specific gravity = 0.7, , 24

Page 24 :

Problem 3, , w, w, , 25

Page 25 :

Types of Fluids, A fluid may be ideal or real., An ideal fluid is a fluid in which there is no friction,, i.e. its viscosity is zero. No resistance is offered when, such a fluid flows. No such fluid exists in nature., Real fluid are those which have viscosity, surface, tension and compressibility in addition to its density., , 26

Page 26 :

1. Ideal Fluid. A fluid, which is incompressible and is having, no viscosity, is known as an ideal fluid. Ideal fluid is only, an imaginary fluid as all the fluids, which exist, have some, viscosity., 2. Real fluid. A fluid, which possesses viscosity, is known as real, fluid. All the fluids: in actual practice, are real fluids., 3. Newtonian Fluid. A real fluid, in which the shear stress is, directly, proportional to the rate of shear strain (or velocity, gradient),, is, known, as, a, Newtonian, fluid., Example: Water, kerosene, air etc., 4. Non-Newtonian fluid. A real fluid, in which shear stress is, not proportional to the rate of shear strain (or velocity, gradient),, known, as, a, Non-Newtonian, fluid., Example: Solution of graphite, solution of polymers, blood, etc., 27

Page 27 :

Capillary Effect, , • Capillary effect is the rise, or fall of a liquid in a smalldiameter tube., • The curved free surface in, the tube is call the, meniscus., • Water meniscus curves up, because water is a wetting, fluid., • Mercury meniscus curves, down because mercury is, a nonwetting fluid., • Force balance can, describe magnitude of, capillary rise.

Page 28 :

Capillarity, , Capillarity is defined as a phenomenon of rise or fall of a liquid surface in a, , small tube relative to the adjacent general level of liquid when the tube is held, vertically in the liquid., The rise of liquid surface is known as capillary rise while the fall of the liquid, surface is known as capillary depression., The attraction (adhesion) between the wall of the tube and liquid molecules is, strong enough to overcome the mutual attraction (cohesion) of the molecules, and pull them up the wall. Hence, the liquid is said to wet the solid surface., It is expressed in terms of cm or mm of liquid. Its value depends upon the, specific weight of the liquid, diameter of the tube and surface tension of the, liquid., , 29

Page 29 :

Capillarity, Expression for Capillary Rise, Consider a glass tube of small, diameter ‘d’ opened at both ends, and is inserted in a liquid, say water., The liquid will rise in the tube, above the level of the liquid., Let h = the height of the liquid in, the tube . Under a state of, equilibrium, the weight of the liquid, of height h is balanced by the force, at the surface of the liquid in the, tube. But the force at the surface of, the liquid in the tube is due to, surface tension., , 30

Page 30 :

Expression for Capillary Rise…, Let σ = Surface tension of liquid, θ = Angle of contact between the liquid and glass tube, The weight of the liquid of height h in the tube, = (Area of the tube x h) x ρ x g, , 31

Page 31 :

Expression for Capillary Rise…, The value of θ between water and clean glass tube is, , approximately equal to zero and hence cos θ is equal to, unity. Then rise of water is given by, , Contact angle depends on both the liquid and the solid., , If θ is less than 90o, the liquid is said to "wet" the solid., However, if θ is greater than 90o, the liquid is repelled by, the solid, and tries not to "wet" it., For example, water wets glass, but not wax. Mercury on the, other hand does not wet glass., , , 32

Page 32 :

Capillarity, , Expression for Capillary Fall, lf the glass tube is dipped in mercury, the revel of, mercury in the tube will be lower than the general level, of the outside liquid as shown above., , 33

Page 33 :

Capillarity, Expression for Capillary Fall, Let h = Height of depression in, , tube., Then in equilibrium, two forces, arc acting on the mercury inside, the tube., First one is due to surface tension, acting in the downward direction, and is equal to σ x πd x cos θ., Second force is due to hydrostatic, force acting upward and is equal, to intensity of pressure at a depth, 'h' x Area, , 34

Page 34 :

Capillarity, Expression for Capillary Fall, , Value of θ for mercury and glass tube is 128o, , 35

Page 35 :

Capillarity…Example 1, Calculate the capillary rise in a glass tube of 2.5 mm, , diameter when immersed vertically in (a) water and (b), mercury. Take surface tensions σ = 0.0725 N/m for, water and σ = 0.52 N/m for mercury in contact with, air. The specific gravity for mercury is given as 13.6, and angle of contact = 130o., , 36

Page 36 :

Capillarity…Example 1, , 37

Page 37 :

Capillarity…Example 2, Find out the minimum size of glass tube that can be used to, , measure water level if the capillary rise in the tube is to be, restricted to 2 mm. Consider surface tension of water in, contact with air as 0.073575 N/m., , 38

Page 38 :

Classification of Fluid Flows, Laminar versus Turbulent Flow, Some flows are smooth and orderly, , while others are rather chaotic., The highly ordered fluid motion, characterized by smooth layers of, fluid is called laminar., The flow of high-viscosity fluids, such as oils at low velocities is, typically laminar., The highly disordered fluid motion, that typically occurs at high, velocities and is characterized by, velocity fluctuations is called, turbulent ., 39

Page 39 :

Classification of Fluid Flows, Laminar versus Turbulent Flow, The flow of low-viscosity fluids, , such as air at high velocities is, typically turbulent., A flow that alternates between, being laminar and turbulent is, called transitional., , 40

Page 40 :

Classification of Fluid Flows, Natural (or Unforced) versus Forced Flow, A fluid flow is said to be natural or forced, depending on, , how the fluid motion is initiated., In forced flow, a fluid is forced to flow over a surface or in, a pipe by external means such as a pump or a fan., In natural flows, any fluid motion is due to natural means, such as the buoyancy effect, which manifests itself as the, rise of the warmer (and thus lighter) fluid and the fall of, cooler (and thus denser) fluid ., In, solar hot-water systems, for example, the, thermosiphoning effect is commonly used to replace pumps, by placing the water tank sufficiently above the solar, collectors., 41

Page 41 :

Classification of Fluid Flows, Steady versus Unsteady Flow, The terms steady and uniform are used frequently in, , engineering, and thus it is important to have a clear, understanding of their meanings., The term steady implies no change at a point with time., The opposite of steady is unsteady., The term uniform implies no change with location, over a specified region., , 42

Page 42 :

Properties of Fluids, Any characteristic of a system is called a property., , Some familiar properties are pressure P, temperature T,, , , , , , , , 43, , volume V, and mass m., Other less familiar properties include viscosity, thermal, conductivity, modulus of elasticity, thermal expansion, coefficient, electric resistivity, and even velocity and, elevation., Properties are considered to be either intensive or extensive., Intensive properties are those that are independent of the mass, of a system, such as temperature, pressure, and density., Extensive properties are those whose values depend on the, size—or extent—of the system. Total mass, total volume V, and, total momentum are some examples of extensive properties.

Page 43 :

Properties of Fluids, An easy way to determine, , whether a property is, intensive or extensive is to, divide the system into two, equal parts with an imaginary, partition., Each part will have the same, value of intensive properties, as the original system, but, half the value of the extensive, properties., , 44

Page 44 :

Properties of Fluids, Density or Mass Density, Density or mass density of a fluid is defined as the ratio of, , the mass of a f1uid to its volume. Thus mass per unit, volume of a fluid is called density. It is denoted the symbol, ρ (rho). The unit of mass density in SI unit is kg per cubic, meter, i.e ., kg/m3., The density of liquids may be considered as constant while, that of gases changes with the variation of pressure and, temperature., Mathematically mass density is written as., Mass of fluid, =, Volume of fluid, The value of density of water is 1 gm/cm3 or 1000 kg/m3., 45

Page 45 :

Properties of Fluids, Density or Mass Density, The density of a substance, in general, depends on, , temperature and pressure., The density of most gases is proportional to pressure and, inversely proportional to temperature., Liquids and solids, on the other hand, are essentially, incompressible substances, and the variation of their, density with pressure is usually negligible., , 46

Page 46 :

Properties of Fluids, Specific weight or Weight Density, Specific weight or weight density of a fluid is the ratio, , between the weight of a fluid to its volume., Thus weight per unit volume of a fluid is called weight, density and it is denoted by the symbol w., Mathematically,, Weight of fluid (Mass of fluid) x Acceleration due to gravity, =, Volume of fluid, Volume of fluid, Mass of fluid x g, =, Volume of fluid, w=, , =x g, w = g, 47

Page 47 :

Properties of Fluids, Specific Volume, Specific volume of a fluid is defined as the volume of a, , fluid occupied by a unit mass or volume per unit mass of a, fluid is called specific volume., Mathematically, it is expressed as, , 1, 1, Volume offluid, =, Specific volume =, =, Mass of fluid , Mass of fluid, Volume, Thus specific volume is the reciprocal of mass density. It is, , expressed as m3/kg., It is commonly applied to gases., 48

Page 48 :

Properties of Fluids, Specific Gravity., Specific gravity is defined as the ratio of the weight density (or, , density) of a fluid to the weight density (or density) of a standard, fluid., For liquids, the standard fluid is taken water and for gases, the, standard fluid is taken air. Specific gravity is also called relative, density. It is dimensionless quantity and is denoted by the symbol S., Weight density (density) of liquid, Weight density (density) of water, Weight density (density) of gas, S(for gases) =, Weight density (density) of air, Thus weight density of a liquid = S x Weight densityof water, = S x 1000x 9.81N/m3, Thus density of a liquid = S x Densityof water, S(for liquids) =, , 32, , = S x 1000kg/m3

Page 49 :

Properties of Fluids, Specific Gravity., If the specific gravity of a, , fluid is known, then the, density of the fluid will be, equal to specific gravity of, fluid multiplied by the, density of water., For example the specific, gravity of mercury is 13.6,, hence density of mercury, = 13.6 x 1000 = 13600, kg/m3., 50

Page 50 :

Properties of Fluids, Example 1., Calculate the specific weight, density and specific gravity of one, liter of a liquid which weighs 7 N., , 51

Page 51 :

Example 2. Calculate the density, specific weight and weight of, one liter of petrol of specific gravity = 0.7, , 52

Page 52 :

Properties of Fluids, , Viscosity, Viscosity is defined as the property of a fluid which offers, , resistance to the movement of one layer of fluid over another, adjacent layer of the fluid., When two layers of a fluid, a distance 'dy' apart move one over, the other at different velocities say u and u+ du as shown in Fig., 1.1 , the viscosity together with relative velocity causes a shear, stress acting between the fluid layers:, , 53

Page 53 :

Properties of Fluids, Viscosity, The top layer causes a shear stress on the adjacent lower, , layer while the lower layer causes a shear stress on the, adjacent top layer., This shear stress is proportional to the rate of change of, velocity with respect to y. It is denoted by symbol τ called, Tau., Mathematically,, , or, , = du, , dy, , 54, , (1.2)

Page 54 :

Properties of Fluids, where μ (called mu) is the constant of proportionality, , and is known as the coefficient of dynamic viscosity or, only viscosity., du, dy, , represents the rate of shear strain or rate of shear, deformation or velocity gradient., From equation (1.2) we have, , , =, , du, dy, , (1.3), , Thus viscosity is also defined as the shear stress, , required to produce unit rate of shear strain., 55

Page 55 :

Properties of Fluids, Unit of Viscosity., The unit of viscosity is obtained by putting the, dimension of the quantities in equation ( 1.3), , SI unit of viscosity =, , Newton second, m2, , 56, , =, , Ns, m2

Page 56 :

Properties of Fluids, Kinematic Viscosity., It is defined as the ratio between the dynamic viscosity and, , density of fluid.lt is denoted by the Greek symbol (ν) called, 'nu' . Thus, mathematically,, , Viscosity , =, =, Density, , , The SI unit of kinematic viscosity is m2/s., , Newton's Law of Viscosity., It states that the shear stress (τ) on a fluid element layer is, directly proportional to the rate of shear strain. The constant, of proportionality is called the co-efficient viscosity., Mathematically, it is expressed as given by equation (1 . 2)., 57

Page 57 :

Properties of Fluids, Fluids which obey the above relation are known as, , Newtonian fluids and the fluids which do not obey the, above relation are called Non-newtonian fluids., Variation of Viscosity with Temperature, Temperature affects the viscosity., The viscosity of liquids decreases with the increase of, temperature while the viscosity of gases increases with, increase of temperature. This is due to reason that the, viscous forces in a fluid are due to cohesive forces and, molecular momentum transfer., In liquids the cohesive forces predominates the molecular, momentum transfer due to closely packed molecules and, with the increase in temperature, the cohesive forces, decreases with the result of decreasing viscosity., 58

Page 58 :

Properties of Fluids, But in the case of gases the cohesive force are small and, , molecular momentum transfer predominates. With the, increase in temperature, molecular momentum transfer, increases and hence viscosity increases. The relation between, viscosity and temperature for liquids and gases are:, , , 1, , (i) For liquids, = o , 2, 1+ t + t , where = Viscosityof liquid at t oC, in poise, , 1 poise =, , 1 Ns, 10 m2, , o = Viscosity of liquid at 0oC,in poise, , = are constants for theliquid, For water, μ o = 1.79 x 10 -3 poise, = 0.03368and =0.000221, = o + t − t 2, (ii) For a gas,, where for air o = 0.000017, = 0.000000056, = 0.1189x 10 -9, 42

Page 59 :

Types of Fluids, 1. Ideal Fluid. A fluid, which is incompressible and is, having no viscosity, is known as an ideal fluid. Ideal, fluid is only an imaginary fluid as all the fluids, which, exist, have some viscosity., 2. Real fluid. A fluid, which possesses viscosity, is known as, real fluid. All the fluids: in actual practice, are real fluids., 3., Newtonian Fluid. A real fluid, in which the shear stressis, directly, proportional to the rate of shear strain (or, velocity gradient), is known as a Newtonian fluid., 4. Non-Newtonian fluid. A real fluid, in which shear stress, is not proportional to the rate of shear strain (or velocity, gradient), known as a Non-Newtonian fluid., 60

Page 60 :

Types of Fluids, 5. Ideal Plastic Fluid., A fluid, in which shear, stress is more than the, yield value and shear, stress is proportional, to the rate of shear, strain (or velocity, gradient), is known as, ideal plastic fluid., , 61

Page 61 :

Example 3, If the velocity distribution over a plate is given by, 2, u = y − y2, 3, in which u is velocity in metre per second at a distance y, metre above the plate, determine the shear stress at y = 0, and y= 0.15 m. Take dynamic viscosity of fluid as 8.63, poises., , 62

Page 62 :

63

Page 63 :

Example 4, Calculate the dynamic viscosity of an oil, which is used for, lubrication between a square plate of size 0.8 m x 0.8 m and an, inclined plane with angle of inclination 30o as shown in Fig. 1.4., The weight of the square plate is 300 N and it slides down the, inclined plane with a uniform velocity of 0.3 m/s. The thickness, of oil film is 1.5 mm., , Fig.1.4, 64

Page 64 :

65

Page 65 :

Example 5, The space between two square flat parallel plates is filled with, oil. Each side of the plate is 60 cm. The thickness of the oil, film is 12.5 mm. The upper plate, which moves at 2.5 metre per, sec requires a force of 98.1 N to maintain the speed., Determine : ·, i. the dynamic viscosity of the oil, and, ii.the kinematic viscosity of the oil if the specific gravity of the, oil is 0.95., Solution. Given:, Each side of a square plate = 60 cm = 0.6 m, Area, A= 0.6 x 0.6 = 0.36 m2, Thickness of oil film dy = 12.5 mm = 12.5 x 10-3 m, Velocity of upper plate u = 2.5 m/s, 66

Page 66 :

67

Page 67 :

Thermodynamic Properties, Fluids consist of liquids or gases. But gases are compressible, , fluids and hence thermodynamic properties play an important, role., With the change of pressure and temperature, the gases undergo, large variation in density., The relationship between pressure (absolute), specific volume, and temperature (absolute) of a gas is given by the equation of, state as, , 68

Page 68 :

Thermodynamic Properties, J, The value of gas constant R is R = 287, kg.K, Isothermal Process. If the changes in density occurs at, , constant temperature, then the process is called isothermal, and relationship between pressure (p) and density (ρ) is, given by, p, , ρ, , = constant, , Adiabatic Process. If the change in density occurs with no, , heat exchange to and from the gas, the process is called, adiabatic. And if no heat is generated within the gas due to, friction, the relationship between pressure and density is, given by, 69, , p, = constant, k, ρ

Page 69 :

Thermodynamic Properties, where k = Ratio of specific heat of a gas at constant, , pressure and constant volume., k = 1.4 for air, , 70

Page 70 :

Compressibility and Bulk Modulus, Compressibility is the reciprocal of the bulk modulus of, , , , , , , , , , , 71, , elasticity, K which is defined as the ratio of compressive, stress to volumetric strain., Consider a cylinder fitted with a piston as shown in the Fig., Let V= Volume of a gas enclosed in the cylinder, p =Pressure of gas when volume is V, Let the pressure is increased to p+ dp, the volume of gas, decreases from V to V – dV., Then increase in pressure = dp, Decrease in volume = dV, Volumetric strain = - dV/V

Page 72 :

Surface Tension and Capillarity, Surface tension is defined as the tensile force acting on the, , , , , , , 73, , surface of a liquid in contact with a gas or on the surface, between two immiscible liquids such that the contact, surface behaves like a membrane under tension., Surface tension is created due to the unbalanced cohesive, forces acting on the liquid molecules at the fluid surface., Molecules in the interior of the fluid mass are surrounded, by molecules that are attracted to each other equally., However, molecules along the surface are subjected to a net, force toward the interior., The apparent physical consequence of this unbalanced, force along the surface is to create the hypothetical skin or, membrane.

Page 73 :

Surface Tension and Capillarity, A tensile force may be, , considered to be acting in the, plane of the surface along any, line in the surface., The intensity of the molecular, attraction per unit length along, any line in the surface is, called the surface tension., It is denoted by Greek letter σ, (called sigma)., The SI unit is N/m., , 74

Page 74 :

Surface Tension and Capillarity, Surface Tension on liquid Droplet and, Bubble, Consider a small spherical droplet of a, liquid of radius ‘R'. On the entire, surface of the droplet, the tensile force, due to surface tension will be acting., Let σ = surface tension of the liquid, P= Pressure intensity inside the, droplet (in excess of the outside, pressure intensity), R= Radius of droplet., Let the droplet is cut into two halves., The forces acting on one half (say left, half) will be, 75

Page 75 :

Surface Tension and Capillarity, (i) tensile force due to, , surface tension acting, around the circumference, of the cut portion as, shown and this is equal to, = σ x Circumference, = σ x 2πR, (ii) pressure force on the, , area (π/4)d2 and, = P x πR2 as shown, , 76

Page 76 :

Surface Tension and Capillarity, These two forces will be equal and opposite under, , equilibrium conditions, i.e.,, , A hollow bubble like a soap bubble in air has two surfaces, , in contact with air, one inside and other outside. Thus two, surfaces are subjected surface tension., , 77

Page 77 :

Surface Tension……. Example 1, Find the surface tension in a soap bubble of 40 mm, , diameter when the inside pressure is 2.5 N/m2 above, atmospheric pressure., , 78

Page 78 :

Surface Tension……. Example 2, The pressure outside the droplet of water of diameter, , 0.04 mm is 10.32 N/cm2 (atmospheric pressure)., Calculate the pressure within the droplet if surface, tension is given as 0.0725 N/m of water., , 79

Page 79 :

Surface Tension and Capillarity, Capillarity, Capillarity is defined as a phenomenon of rise or fall of a, , liquid surface in a small tube relative to the adjacent general, level of liquid when the tube is held vertically in the liquid., The rise of liquid surface is known as capillary rise while, the fall of the liquid surface is known as capillary, depression., The attraction (adhesion) between the wall of the tube and, liquid molecules is strong enough to overcome the mutual, attraction (cohesion) of the molecules and pull them up the, wall. Hence, the liquid is said to wet the solid surface., It is expressed in terms of cm or mm of liquid. Its value, depends upon the specific weight of the liquid, diameter of, the tube and surface tension of the liquid., 80

Page 80 :

Surface Tension and Capillarity, , 81, , Expression for Capillary Rise, Consider a glass tube of small, diameter ‘d’ opened at both ends, and is inserted in a liquid, say water., The liquid will rise in the tube, above the level of the liquid., Let h = the height of the liquid in, the tube . Under a state of, equilibrium, the weight of the liquid, of height h is balanced by the force, at the surface of the liquid in the, tube. But the force at the surface of, the liquid in the tube is due to, surface tension.

Page 81 :

Expression for Capillary Rise…, Let σ = Surface tension of liquid, θ = Angle of contact between the liquid and glass tube, The weight of the liquid of height h in the tube, = (Area of the tube x h) x ρ x g, , 82

Page 82 :

Expression for Capillary Rise…, The value of θ between water and clean glass tube is, , approximately equal to zero and hence cos θ is equal to, unity. Then rise of water is given by, , Contact angle depends on both the liquid and the solid., , If θ is less than 90o, the liquid is said to "wet" the solid., However, if θ is greater than 90o, the liquid is repelled by, the solid, and tries not to "wet" it., For example, water wets glass, but not wax. Mercury on the, other hand does not wet glass., , , 83

Page 83 :

Capillarity, , Expression for Capillary Fall, lf the glass tube is dipped in mercury, the revel of, mercury in the tube will be lower than the general level, of the outside liquid as shown above., , 84

Page 84 :

Capillarity, Expression for Capillary Fall, Let h = Height of depression in, , tube., Then in equilibrium, two forces, arc acting on the mercury inside, the tube., First one is due to surface tension, acting in the downward direction, and is equal to σ x πd x cos θ., Second force is due to hydrostatic, force acting upward and is equal, to intensity of pressure at a depth, 'h' x Area, 85

Page 85 :

Capillarity, Expression for Capillary Fall, , Value of θ for mercury and glass tube is 128o, , 86

Page 86 :

Capillarity…Example 1, Calculate the capillary rise in a glass tube of 2.5 mm, , diameter when immersed vertically in (a) water and (b), mercury. Take surface tensions σ = 0.0725 N/m for, water and σ = 0.52 N/m for mercury in contact with, air. The specific gravity for mercury is given as 13.6, and angle of contact = 130o., , 87

Page 87 :

Capillarity…Example 1, , 88

Page 88 :

Capillarity…Example 2, Find out the minimum size of glass tube that can be used to, , measure water level if the capillary rise in the tube is to be, restricted to 2 mm. Consider surface tension of water in, contact with air as 0.073575 N/m., , 89

Page 89 :

Flow Analysis Techniques, In analyzing fluid motion,, , 90, , we might take one of two, paths:, 1. Seeking an estimate of, gross effects (mass flow,, induced force, energy, change) over a finite, region or control volume, or, 2. Seeking the point-bypoint details of a flow, pattern by analyzing an, infinitesimal region of, the flow.

Page 90 :

Flow Analysis Techniques, The control volume technique is useful when we are, , interested in the overall features of a flow, such as mass, flow rate into and out of the control volume or net forces, applied to bodies., Differential analysis, on the other hand, involves, application of differential equations of fluid motion to any, and every point in the flow field over a region called the, flow domain., When solved, these differential equations yield details, about the velocity, density, pressure, etc., at every point, throughout the entire flow domain., , 91

Page 91 :

Flow Patterns, Fluid mechanics is a highly visual subject. The patterns of flow, , can be visualized in a dozen different ways, and you can view, these sketches or photographs and learn a great deal, qualitatively and often quantitatively about the flow., Four basic types of line patterns are used to visualize flows:, 1. A streamline is a line everywhere tangent to the velocity, vector at a given instant., 2. A pathline is the actual path traversed by a given fluid, particle., 3. A streakline is the locus of particles that have earlier passed, through a prescribed point., 4. A timeline is a set of fluid particles that form a line at a, given instant., 92

Page 92 :

Flow Patterns, The streamline is convenient to calculate mathematically,, , , , , , , 93, , while the other three are easier to generate experimentally., Note that a streamline and a timeline are instantaneous lines,, while the pathline and the streakline are generated by the, passage of time., A streamline is a line that is everywhere tangent to the, velocity field. If the flow is steady, nothing at a fixed point, (including the velocity direction) changes with time, so the, streamlines are fixed lines in space., For unsteady flows the streamlines may change shape with, time., A pathline is the line traced out by a given particle as it flows, from one point to another.

Page 93 :

Flow Patterns, A streakline consists of all particles in a flow that have, , previously passed through a common point. Streaklines are, more of a laboratory tool than an analytical tool., They can be obtained by taking instantaneous photographs of, marked particles that all passed through a given location in, the flow field at some earlier time., Such a line can be produced by continuously injecting, marked fluid (neutrally buoyant smoke in air, or dye in water), at a given location., If the flow is steady, each successively injected particle, follows precisely behind the previous one forming a steady, streakline that is exactly the same as the streamline through, the injection point., 94

Page 94 :

Flow Patterns, , (a) Streamlines, 95, , (b) Streaklines

Page 95 :

Flow Patterns, Streaklines are often confused with streamlines or pathlines., While the three flow patterns are identical in steady flow, they, , can be quite different in unsteady flow., The main difference is that a streamline represents an, instantaneous flow pattern at a given instant in time, while a, streakline and a pathline are flow patterns that have some age, and thus a time history associated with them., If the flow is steady, streamlines, pathlines, and streaklines are, identical, , 96

Page 96 :

Dimensions and Units, Fluid mechanics deals with the measurement of many, , variables of many different types of units. Hence we need, to be very careful to be consistent., Dimensions and Base Units, The dimension of a measure is independent of any, particular system of units. For example, velocity may be, inmetres per second or miles per hour, but dimensionally, it, is always length per time, or L/T = LT−1 ., The dimensions of the relevant base units of the Système, International (SI) system are:, , 97

Page 97 :

Dimensions and Units, , Derived Units, , 98

Page 98 :

99

Page 99 :

Unit Table, Quantity, , SI Unit, , English Unit, , Length (L), , Meter (m), , Foot (ft), , Mass (m), , Kilogram (kg), , Time (T), , Second (s), , Slug (slug) =, lb*sec2/ft, Second (sec), , Temperature ( ), , Celcius (oC), , Farenheit (oF), , Force, , Newton, (N)=kg*m/s2, , Pound (lb), , 10, 0

Page 100 :

Dimensions and Units…, 1 Newton – Force required to accelerate a 1 kg of mass, , to 1 m/s2, 1 slug – is the mass that accelerates at 1 ft/s2 when acted, upon by a force of 1 lb, To remember units of a Newton use F=ma (Newton’s 2nd, Law), [F] = [m][a]= kg*m/s2 = N, , To remember units of a slug also use F=ma => m = F / a, [m] = [F] / [a] = lb / (ft / sec2) = lb*sec2 / ft, , 10, 1