Page 2 : Tel./Fax: +4205 4321 1134, E-mail:

[email protected], www.ta-service.cz, , PROGRAMME, Session A, A1, , Water Supply System - Field Measurement, A STUDY ON THE WATER AND ENERGY CONSUMPTION, IN NURSING HOMES FOR THE ELDERY, D. Nishina, S. Murakawa, H. Takata, T. Itai, Japan, , A2, , A STUDY ON BATHING BEHAVIOR AND HOT WATER USAGE, IN NURSING HOMES FOR THE AGED, A. Takaaze, S. Murakawa, D. Nishina, T. Itai, Japan, , A3, , DOMESTIC WATER CONSUMPTION AND ITS IRREGULARITY, , A4, , DOMESTIC HOT WATER CONSUMPTION IN ESTONIAN, APARTMENT BUILDINGS, , V. Suurkask, J. Säärekönno, Estonia, , A. Toodle, T.A. Köiv, Estonia, , A5, , A STUDY ON THE LOADS OF HOT WATER CONSUMPTION, IN HOUSES WITH THE HOT WATER STORAGE TANK SYSTEM, (PART 1) AN ANALYSIS OF THE HOT WATER USAGE AND THE, LOADS OF HOT WATER CONSUMPTION, N. Yamamoto, S. Murakawa, H. Takata,, H. Kitayma, Y. Hamada, M. Nabeshima, Japan, , A6, , A STUDY ON THE LOADS OF HOT WATER CONSUMPTION, IN HOUSES WITH THE HOT WATER STORAGE TANK SYSTEM, (PART 2) CALCULATIONS FOR THE LOADS OF HOT WATER, CONSUMPTION, , H. Takata, S. Murakawa, N. Yamamoto, H. Kitayma, Y. Hamada,, M. Nabeshima, Japan, , A7, , DEMAND ANALYSIS OF FRESH WATER SUPPLY FOR, A CHINESE RESTAURANT, K.W. Mui, L.T. Wong, M. K. Yeung, P.S. Hui, China, , Session B, , Water Supply System - Calculation Methods, Modelling, , B1, , CALCULATION FOR THE COLD AND HOT WATER DEMANDS, IN THE GUEST ROOMS OF CITY HOTEL, S. Murakawa, Y. Koshikawa, H. Takata, A. Tanaka, Japan, , B2, , MODELLING OF DOMESTIC HOT WATER TANK SIZE, FOR APARTMENT BUILDINGS II, L. Bárta, Czech Republic

Page 4 :

J.A. Swaffield, United Kingdom, , D7, , APPLICATION OF RENEUAL ASSESSMENT MODEL, IN BUILDING DRAINAGE SYSTEM, C. J. Yen, C. L. Cheng, K. C. Ho, W. L. Lee, Taiwan, , D8, , WATER- AND ENERGY SAVING ON WATER SYSTEMS, , Session E, , Testing Methods, Operation, Standardization, and Industrial Developments, , E1, , ASSESSMENT OF WATER SUPPLY AND DRAINAGE SYSTEMS, FOR AN HISTORICAL HAMMAM BY USING NON-DESTRUCTIVE, METHODS, , W.G. van der Schee, The Netherlands, , G. Disli, A. Tavukcuoglu, L. Tosun, E. N. Caner-Saltik, Turkey,, E. Grinzato, Italy, , E2, , IDENTIFICATION OF DEPLETED APPLIANCE TRAP SEALS, WITHIN THE BUILDING DRAINAGE AND VENTILATION, SYSTEM – A TRANSIENT-BASED TECHNIQUE, J.A. Swaffield, United Kingdom, , E3, , AN INDESTRUCTIBLE TESTING METHOD FOR AIR PRESSURE, DISTRIBUTION IN STACK OF BUILDING DRAINAGE SYSTEM, K. C. He, C. L. Cheng, L.T. Wong, P.S. Hui, W. R. Liao, Taiwan, , E4, , A STUDY ON THE TEST METHOD OF TRAP PERFORMANCE, , E5, , FLUSH QUALITY OF WC PANS, , E6, , STUDY ON THE CORROSION OF STEEL AND ZINC WITH, FLOW VELOCITY AND CORROSION CONTROL BY THE VACUUM, MEMBRANE DEAERATION SYSTEM IN TAP WATER ANALYSIS, ON THE CORROSION OF STEEL AND ZINC AND GALVANIC, CORROSION OF GUNMETAL/ GALVANIZED STEEL PIPES, , K. Sakaue, M. Kamata, Y Zhang, Japan, , T. Seelig, Ch. Henke, M. Demiriz, Germany, , T. Yamate, S. Murakawa, Japan, , E7, , STUDY OF PATHOLOGIES IN WATER AND DRAINAGE, PLUMBING SYSTEMS, S. V. de Amorim, A. P. da Conceiçăo, L.M. Ferrante,, Ry. De V. Guimarăes, Brazil, , E8, , PRESENT STATE AND FUTURE CHALLENGE ON INSTALLATION, NUMBER OF THE SANITARY FIXTURE, H. Kose, Japan, , E9, , MYTHS AND LEGENDS: DEVELOPMENTS TOWARDS MODERN, SANITARY ENGINEERING, M. Gormley, United Kingdom

Page 5 :

E10, , ACTIVE AIR PRESSURE SUPPRESSION OF DRAINAGE SYSTEMS, - FROM RESEARCH TO THE MARKETPLACE, S. White, United Kingdom, , Session F, , Drainage Systems – Hydraulic, , F1, , INFLUENCE OF UNSTEADY FRICTION ON TRAP, SEAL DEPLETION, J.A. Swaffield, United Kingdom, , F2, , STUDIES OF A TESTING METHOD FOR AIR ADMITTANCE VALVE, CHARACTERISTICS AND A DESIGN METHOD FOR VENT PIPES, M. Otsuka, J. Ma, Japan, , F3, , INFLUENCE OF FLOW CAPACITY ON THE VENT SYSTEM, OF A DRAINAGE SYSTEM GRASP OF THE VENTILATION CAPACITY, BY FIXTURE DRAINAGE LOAD, N. Honngo, M. Otsuka, K. Kawasaki, Japan, , F4, , A NUMERICAL APPROACH TO INVESTIGATE SOLID TRANSPORT, CHARACTERISTICS IN WASTE WATER DRAINAGE SYSTEMS, A. Öngören, B. Meier, Switzerland, , F5, , EXPERIMENTAL STUDY OF DRAINAGE CHARACTERISTICS, OF WATER SAVING TOILET BOWLS AND TRANSPORT, PERFORMANCE EVALUATION, T. Ishii, M. Otsuka, Japan, , F6, , NOVEL SIPHONIC ROOF DRAINAGE DEVICES, , F7, , THE PRIMING FOCUSSED DESIGN OF SIPHONIC ROOF DRAINAGE, , F8, , A STUDY ON THE SIPHON DRAINAGE SYSTEM, , D.P. Campbell, United Kingdom, , S. Arthur, United Kingdom, , N. Tsukagoshi, K. Sakaue, Japan

Page 6 : A Study on the Water and Energy Consumption in, Nursing Homes for the Elderly, , A1), , Daisaku Nishina (1), Saburo Murakawa (2),, Hiroshi Takata (3) and Takanori Itai (4), (1)

[email protected], (2)

[email protected], (3)

[email protected], (4)

[email protected], (1), (2), (4) Graduate School of Engineering, Hiroshima Univ., Japan, (3) Graduate School of Educating, Hiroshima Univ., Japan, , Abstract, Recently, Japan is facing fast-aging society according to the birthrate declining, and the improvement in life expectancy. In parallel with the change of social condition,, the new care styles, such as day-care, home care, etc. have been introduced. As for, nursing homes for the elderly, not only the quantitative expansion of homes, but also the, qualitative enhancement of facilities and equipments are required more in order to, improve quality of life of the residents., However, in regards to the new type of nursing homes, the data is not sufficient for, the planning and designing of building systems. The purpose of this study is to clarify, the actual condition of water and energy consumption of the home and to obtain the, fundamental data for design. Therefore, the measurements of hot and cold water and, energy consumption were carried out in two nursing homes called Facility T and, Facility S. The measurement periods were approximately two weeks in winter and one, week in summer. Because Facility T and Facility S utilize electricity and liquefied, petroleum gas respectively, as an energy source of hot water supply, Facility T has a, heat storage unit with heat pump and Facility S has a boiler and a hot water storage, tank. There are dining rooms, recreation rooms, bathrooms and private rooms for, residents in both facilities. Well water is used for flushing the toilets in both facilities,, and Facility S uses well water for the bathrooms., In this paper, the daily and hourly consumption of cold and hot water in each, season are shown and the relation between the water consumption and the daily, schedule of the residents and the caregivers in two facilities are examined., , 3

Page 7 :

Keywords, Elderly Nursing Home, Hot Water Consumption, Cold Water Consumption,, , 1. Introduction, The purpose of this study is to collect basic information of current equipment design, of elderly nursing homes aiming at energy conservation planning. The authors measured, the consumption of cold and hot water and energy consumption at two elderly nursing, homes called Facility T and Facility S in order to understand actual usage of cold and, hot water. In this study, the facility overview (Facility T and Facility S) shall be, reported to compare and investigate the loads of cold and hot water usage in both, facilities., , 2. Outline of the investigation, 2.1 Outline of the facilities, The facilities surveyed are Facility T an all-electric facility and Facility S which is, on the same scale as Facility T but uses a gas heat source. Facility T and S are located in, the northeast and the northwest of Hiroshima prefecture, respectively. Facility T is an, elderly nursing home with a care house for the elderly who do not need any help., Facility S is a special elderly nursing home, also a care house, short stay center and a, day service center are attached to this facility., Table 1 shows the overview of each facility. Both facilities have a central hot water, supply system and in both facilities hot water is supplied to the common areas such as, the bathing room and laundry room. Facility T has two bathrooms each for the elderly, nursing home and the care house. Also, Facility S has two bathrooms each for the, special elderly nursing home, the care house and the day service center. Facility T, utilizes city water as the, Table 1 Overview of two facilities, Facility T, Building use, Total floor area (• ), Number of stories, Location, Capacity of people, Heat source for hot water supply, Hot water apparatus, , Hot water storage tank • L•, , Nursing home, Care house, Short stay, 3,797.86, 3, Hiroshima pref.Syobara city, 51.00, Electricity, Heat storage unit for hot water supply, Performance of heating • kW•, Electric capacity • kW•, 10,200, , 4, , Facility S, 28 Special elderly nursing home, 20 Care house, 3, 4,043.90, 2, Hiroshima pref.Kitahiroshima city, 77.00, , 50, 27, , Gas, Hot water heater, 90 Performance of heating • kJ/h•, 1,465,100, 33 Hot water consumption (L/h), 6,500 (0°C→50°C), 3, 17.2(LPG•, Fuel consumption • m /h•, 4,000

Page 8 :

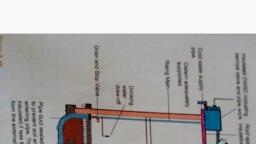

Cold water (City water), Cold water (Well water), , Hot water (Supply), Hot water (Return), , Heat exchager, , Care house Elderly nursing home, 7, M T, , Heat pump, , Kitchen, Cold water, (City water), , 5 6, M, , M4, , Cold water, (Well water), , T, , 1, , Electric, hot water, heater, , Heat storage unit, for hot water supply, , T, , 10, , M T, T, , 13, , M T, , 15, , M T, , 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, , Bathing rooms,, Laundry rooms, etc., Bathing rooms,, Laundry rooms,, Private rooms, etc., , 16, , 3, , M T, , 2, , Toilet, , M, , Facility T, , M, T, , Gas, hot water, boiler, , Ultrasonic flow meter, Temperature sensor, , Bathing room of, day service center, , Hot water, storage tank, , 4M, , 5, , M, , 10, , M, , Kitchen, 6, , 7M, , T, , 8, , M, , Cold water 3M, (City water), , 9, , M, , Bathing rooms,, Private rooms,, etc., Bathing rooms,, Private rooms,, Dining, etc., Bathing rooms,, Private rooms,, etc., , Cold water 1 2, M, T, (Well water), , Facility S, , Figure 1 Cold and hot water supply system of two facilities, Table 2 Measurement items of two facilities, Facility T, Number, 1, Total flow rate of cold water (City water), 2, Total flow rate of cold water (Well water), 3, Temperature of cold water (City water), 4, Flow rate of cold water for a kitchen, Flow rate of hot water for a kitchen, 5, Temperature of hot water for a kitchen, 6, 7, Flow rate of hot water for heating up (Supply), Bathing rooms, 8, Temperature of hot water for heating up (Supply), of a care house, 9, Temperature of hot water for heating up (Return), 10, Bathing rooms Flow rate of hot water for heating up (Supply), of a elderly, 11, Temperature of hot water for heating up (Supply), nursing home Temperature of hot water for heating up (Return), 12, 13, Total flow rate of hot water (Supply), 14, Temperature of hot water (Supply), 15, Total flow rate of hot water (Return), 16, Temperature of hot water (Return), * The number corresponds to the number of measuring point in Figure 1., , 5, , Facility S, Total flow rate of cold water (Well water), Temperature of cold water (Well water), Total flow rate of cold water (City water), Flow rate of hot water for bathing rooms for day service, Total flow rate of hot water (Supply), Temperature of hot water (Supply), Flow rate of hot water for a kitchen (Supply), Flow rate of hot water for a kitchen (Return), Flow rate of hot water except for a kitchen (Return), Total flow rate of hot water (Return)

Page 9 :

source of the hot water supply while Facility S utilizes well water. In Facility T, an, electric water heater is equipped to each private room and to the kitchen. In Facility S,, an electric water heater is equipped in each dining hall. In this research, these individual, hot water supply system had been excluded from the measurement. However, the, kitchen electrical water heater in Facility T was included., 2.2 Outline of the measurements, In this study, wide-ranging measurements were taken during the summer and winter, months. The measurement items were divided into three groups, the energy, consumption such as the electricity and gas used, the cold and hot water consumption, and the indoor thermal environment. This paper shows the outline of the cold and hot, water consumption measurements., Figure 1 shows the cold and hot water supply system along with the major, measurement points. Table 2 shows the measurement items for each facility. In regards, to the measurement item 7 and 10 in Facility T, the water supply is circulated with, constant flow for the bathing room water heat up, thus the measurement was, implemented only during the winter. Using an ultrasonic flow meter to measure water, flow and using a surface temperature sensor for water temperature measurements,, sequential measurements were recorded automatically at one-minute intervals. The, period of the measurements of the cold and hot water consumption in both facilities, were 1 to 2 weeks for each season in 2004 and the same period was used for the energy, consumption measurements., Table 3 shows the measurement period and statistics of the outside air temperature, during the same period. Based on this table, it can be seen that the temperature in winter, is slightly lower at Facility T compared to Facility S. The average winter temperature at, Facility T is –0.6 °C, and the temperature remains below zero for the entire, measurement period. In particular, the lowest average temperature per day of –5.1 °C, was recorded on January 22. On the other hand, the summer time shows the opposite, trend as Facility T has a higher temperature than Facility S. However, this tendency may, be affected by the measurement period., Table 3 Measurement periods and outside air temperature, Standard, Maximum, Average, value[°C] deviation[°C] value[°C], -0.6, 2.1, 2.5, 25.0, 1.9, 26.9, 2.2, 1.7, 4.9, 23.7, 2.4, 25.9, , Period of measurement, Facility T, Facility S, , Winter, Summer, Winter, Summer, , 16 1.2004 - 29 1.2005, 25 8.2004 - 2 9.2004, 3 2.2004 - 15 2.2004, 15 9.2004 - 23 9.2004, , Minimum, value[°C], -5.1, 21.2, -0.3, 19.3, , Table 4 Temperatures of hot and cold water, Cold water, (City water) [°C], Facility T, Facility S, , Winter, Summer, Winter, Summer, , Cold water, (Well water) [°C], , Hot water storage, tank [°C], , 9.4, 21.5, 16.0, 22.3, , 52.2, 55.1, 55.2, 55.6, , 4.3, 24.4, 10.8, 28.2, , 6, , Hot water for a, kitchen[°C], 71.0, 75.3, -

Page 10 :

3. The consumption of cold and hot water, 3.1 Temperatures of cold and hot water, Table 4 shows the average temperature of the cold and hot water for each season., Hot water storage tank temperature indicates when the water is supplied from the tank, to the common area, and the temperature of the hot water for a kitchen at Facility T, indicates when the water is supplied from the electric water heater to the kitchen. The, hot water average temperature is based on the data when the water heater operates., From the above table, it can be seen that the hot water storage tank supplies water at 50, °C for each season., 3.2 Daily consumption of cold and hot water, Table 5 shows the statistics of daily consumption of the cold and hot water in both, facilities. The cold water consumption figures shown in table 5 are the combined values, of both the city water and well water, except for the hot water. Also, the hot water, Table 5 Daily consumption of hot and cold water, Facility T, , Actual value, Basic unit, , Winter, 31.292, 1.983, 34.062, 26.631, 11.573, 1.423, 13.843, 8.827, 6.106, 0.571, 6.945, 4.678, 5.556, 1.010, 6.898, 3.856, 8.239, 0.522, 8.969, 7.012, 3.047, 0.375, 3.645, 2.324, 1.608, 0.150, 1.829, 1.232, 1.463, 0.266, 1.816, 1.015, , Total of cold and Avarege value, hot water, Standard deviation, consumption Maximum value, 3, Minimum value, [m ], Avarege value, Hot water, Standard deviation, 3, consumption [m ] Maximum value, Minimum value, Avarege value, For a kitchen Standard deviation, 3, Maximum value, [m ], Minimum value, Avarege value, For bathing Standard deviation, 3, rooms [m ] Maximum value, Minimum value, Total of cold and Avarege value, hot water, Standard deviation, consumption Maximum value, 2, Minimum value, • L/m • d•, Avarege value, Hot water, Standard deviation, consumption, Maximum value, 2, [L/m • d], Minimum value, Avarege value, For a kitchen Standard deviation, 2, [L/m • d] Maximum value, Minimum value, For bathing Avarege value, Standard deviation, rooms, Maximum value, 2, [L/m • d], Minimum value, , 7, , Summer, 31.464, 2.111, 34.884, 27.976, 11.742, 1.781, 14.414, 9.037, 5.881, 0.567, 6.761, 5.141, 5.861, 1.377, 8.261, 3.801, 8.285, 0.556, 9.185, 7.366, 3.092, 0.469, 3.795, 2.379, 1.548, 0.149, 1.780, 1.354, 1.543, 0.363, 2.175, 1.001, , Facility S, Winter, 30.791, 9.506, 41.566, 15.825, 13.661, 5.750, 21.183, 4.819, 5.981, 2.018, 9.833, 2.567, 7.680, 4.331, 14.739, 1.576, 7.614, 2.351, 10.279, 3.913, 3.378, 1.422, 5.238, 1.192, 1.479, 0.499, 2.432, 0.635, 1.899, 1.071, 3.645, 0.390, , Summer, 27.613, 9.819, 39.694, 13.463, 7.859, 4.671, 15.013, 1.906, 2.915, 0.839, 4.297, 1.430, 4.944, 4.136, 11.750, 0.377, 6.828, 2.428, 9.816, 3.329, 1.943, 1.155, 3.713, 0.471, 0.721, 0.207, 1.063, 0.354, 1.223, 1.023, 2.906, 0.093

Page 11 :

12, , Hot water consumption, , Cold water consumption, , Hot water consumption, , Cold water consumption, , 10, , 10, , 8, , 8, , 6, , 6, , 4, , 4, 2, , Facility T, , 0, , 9/15, 9/16, 9/17, 9/18, 9/19, 9/20, 9/21, 9/22, 9/23., , 8/25, 8/26, 8/27, 8/28, 8/29, 8/30, 8/31, 9/1, 9/2., , 1/16, 1/17, 1/18, 1/19, 1/20, 1/21, 1/22, 1/23, 1/24, 1/25, 1/26, 1/27, 1/28, 1/29, , 2, 2/3, 2/4, 2/5, 2/6, 2/7, 2/8, 2/9, 2/10, 2/11, 2/12, 2/13, 2/14, 2/15, , Basic unit of cold and hot water, consumption, [L/ d], , 12, , 0, , Basic unit of cold and hot water consumption, [L/ d], , consumption for bathing rooms defines the amount of the hot water supplied by the, central system except for the hot water consumption for a kitchen. The laundry rooms of, Facility T and the laundry and guest rooms of Facility S are included in the figure of the, bathing rooms. In addition, for both facilities, floor area (m2) is used to calculate the, consumption per square meter as the basic unit of consumption., As for the basic unit of total of cold and hot water consumption, both facilities do, not show major differences on a daily average. However, based on the standard, deviation, Facility S shows large variation as a major difference was found between the, maximum and minimum values of daily consumption, though Facility T does not show, such a deviation. On the other hand, when comparing winter and summer averages of, Facility S and Facility T, the facilities show small changes in average or deviation. Each, facility also shows almost the same way of using water in summer and winter., In regards to the hot water consumption, in Facility T, the standard deviation is, smaller than Facility S and there is a small difference of standard deviation between the, seasons in each facility. Also it can be considered as the similar tendency for total, consumption of cold and hot water. In Facility S, there is a difference in the standard, deviation between the seasons. In the summer, hot water consumption is reduced to, 60% of the winter consumption., In the hot water consumption for bathing rooms, the standard deviation is higher, compared with the hot water consumption for a kitchen. This tendency can be seen in, both facilities and it may depend on weekly shower or bath time schedule. The decrease, of the hot water usage during summer in Facility S can be seen in the hot water, consumption for a kitchen and bathing rooms as well, but it is expected that the water, for the dish washing in the kitchen and cleaning the bathing rooms may have changed to, cold water from hot water in the summer., Figure 2 shows the daily variation of the basic unit of cold and hot water, consumption in Facility T and Facility S respectively. As for the percentage of the hot, water consumption of the total consumption of cold and hot water, in Facility T, it, accounts for 37.6% in winter and 37.3% in summer. Also, in Facility S, it accounts for, 44.4% for winter and 28.5% for summer. As above, Facility T shows a stabilized, percentage for both cold and hot water consumption, however, as stated previously,, there are major changes in cold and hot water usage in Facility S. There are bathing, rooms on the 1st and 2nd floors in Facility S. Water is supplied to the 1st floor bathing, , Facility S, , Figure 2 Basic unit of daily consumption, , 8

Page 12 :

room 2 or 3 times a week in both winter and summer. Water is supplied to the 2nd floor, bathing room 4 times a week during winter and approximately 3 times a week during, summer. These facts may affect on the consumption., Figure 3 shows the percentage of the hot water consumption for bathing rooms and, a kitchen for each season in both facilities. The hot water consumption for a kitchen in, Facility T accounts for 50% of the total consumption of hot water and in Facility S it, accounts for 40% of total. Also, these ratios in both facilities show small variation for, each season., 3.3 Hourly consumption of cold and hot water, Table 6 shows the cold and hot water consumption per hour in both facilities. The, average of hourly consumption of hot water is calculated during a period of 20 hours, from 4 am to 11 pm. As for the peak time of hot water in Facility T, the peak, Winter, Summer, 0%, , 25%, , 50%, , 75% 100% 0%, , 25%, , Facility T, , 50%, , 75% 100%, , Facility S, , For bathing rooms, , For a kitchen, , Figure 3 Percentage of hot water consumption for a kitchen and bathing rooms, Table 6 Hourly consumption of cold and hot water, Facility T, , Actual value, Basic unit, , Average value [L/h], Total of cold and hot Maximum hourly consumption[L/h], water consumption Peak ratio, Time zone of peak occurrence [hour], Average value [L/h], Hot water, Maximum hourly consumption[L/h], consumption, Peak ratio, Time zone of peak occurrence [hour], Average value [L/h], Maximum hourly consumption[L/h], For a kitchen, Peak ratio, Time zone of peak occurrence [hour], Average value [L/h], For bathing Maximum hourly consumption[L/h], rooms, Peak ratio, Time zone of peak occurrence [hour], Total of cold and hot Average value [L/m\2• h], water consumption Maximum hourly consumption [L/m2• h], 2, Hot water, Average value [L/m • h], 2, consumption, Maximum hourly consumption [L/m • h], 2, h], value, [L/m, Average, •, For a kitchen, 2, Maximum hourly consumption [L/m • h], For bathing Average value [L/m2• h], 2, rooms, Maximum hourly consumption [L/m • h], , 9, , Winter, Summer, 1292.34 1311.02, 2755.00 4739.30, 0.09, 0.15, 7, 1, 527.76, 585.77, 2266.00 3196.00, 0.16, 0.25, 11, 20, 288.52, 292.81, 1015.00 1065.00, 0.17, 0.17, 11, 18, 277.37, 292.96, 1950.00 3196.00, 0.39, 0.52, 20, 20, 0.340, 0.345, 0.725, 1.248, 0.139, 0.154, 0.597, 0.842, 0.076, 0.077, 0.267, 0.280, 0.073, 0.077, 0.513, 0.842, , Facility S, Winter, Summer, 1282.94 1150.56, 6309.00 8096.00, 0.16, 0.20, 8, 11, 682.80, 392.95, 3684.00 4141.00, 0.23, 0.32, 8, 5, 299.04, 145.75, 2167.00 1222.00, 0.22, 0.47, 9, 5, 383.76, 247.20, 2865.00 3441.00, 0.30, 0.36, 8, 5, 0.317, 0.285, 1.560, 2.002, 0.169, 0.097, 0.911, 1.024, 0.074, 0.036, 0.536, 0.302, 0.095, 0.061, 0.708, 0.851

Page 13 :

Hot water consumption [L/h], , consumption for a kitchen occurs at 11:00 am when lunch preparation starts. The peak, time for bathing rooms is 8:00 pm, as that is the bathing room cleaning time. As for, Facility S, the peak time of hot water consumption is in the morning when the water is, supplied to the bathing room for filling bath full. In the peak percentage, the value of the, hot water consumption for bathing rooms is higher than others in both facilities., Secondarily, Figure 4 and 5 show the changes of hourly consumption of hot water in, both facilities during summer and winter. According to the results, the variations of hot, water consumption are clarified. As stated previously, as the variation of daily, consumption of hot water is large in Facility S, two and three patterns are divided in, winter and summer, respectively., In Facility T, based on the results in winter, the hot water for bathing room was used, for backwashing of an extraction filter at 6:00 am and 12:00 pm and also, the water was, used for skim removal by intentionally overflowing the water in order to clean the bath, tub in the care house at 10:00 am. The skim removal was implemented after 8:00 pm, when the bathing room was closed, and these are the times when the hot water is used, the most. As for the hot water for a kitchen, similar amount of water is used during, breakfast (5-8 am), lunch (11 am-2 pm) and dinner (5-7pm). These trends stated above, 2000, For bathing rooms, , 1600, , For a kitchen, , 1200, 800, 400, 0, 0, , 2, , 4, , 6, , 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22, , 0, , 2, , 4, , 6, , 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22, , Winter, , Summer, , Hot water consumption [L/h], , Figure 4 Hourly consumption of hot water in Facility T, 4000, 3500, , For bathing rooms, , For a kitchen, , 3000, 2500, 2000, 1500, 1000, 500, 0, 0, , 3, , 6, , 9, , 12, , 15, , 18, , 21, , 0, , 3, , Hot water consumption [L/h], , Winter 1 (n=7), , 6, , 9, , 12, , 15, , 18, , 21, , Winter 2 (n=6), , 4000, 3500, 3000, 2500, 2000, 1500, 1000, 500, 0, 0, , 2, , 4, , 6, , 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22, , 0, , 3, , 6, , 9, , 12, , 15, , 18, , 21, , 0, , 2, , 4, , 6, , 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22, , Summer 1 (n=4), Summer 2 (n=2), Summer 3 (n=3), Figure 5 Hourly consumption of hot water in Facility S, , 10

Page 14 :

can be seen during the summer time as well. Additionally, the hot water consumption, for cleaning the bathing room at 8 pm is more significant in summer., On the other hand, the variation for Facility S is divided into several patterns. The, winter water usage is broken into 2 patterns. The pattern Winter 1 is the days when the, hot water was supplied to the day service bathing room for filling up water in the, bathtub. The pattern Winter 2 is the days when no hot water was supplied to the day, service bathing room. The summer is broken into 3 patterns with Summer 1 and 2 the, same as Winter 1 and 2 respectively, but in addition, Summer 3 is for the days when, there was no bathing room usage., As for the period Winter 1, the day service user used the bathing room on Monday,, Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, on these days hot water is supplied to fill up water in, the bathtub at 8 am. Also in the morning, there were lifting shower times and bathing, with mechanical bathtubs for the special elderly nursing home and bathing in the day, service center. In the afternoon, the bathing room was used for the care house until 4 pm, so that the hot water consumption per hour goes up during these periods. From 8 pm to, 9 pm, hot water was used for cleaning the bathing room. For the hot water consumption, per hour for a kitchen, the time when hot water is used is different from Facility T,, however a similar tendency can be found that the hot water consumption increases, during three different periods in a day. In Winter 2, there was bathing time for the, special elderly nursing home and for the care house in the morning and the afternoon, respectively, but the consumption of hot water is low. Also, Winter 2 includes Sunday, , Table 7 Daily heat amounts for hot water, Facility T, , Heat load, [MJ/d], Actual value, , For a kitchen, [MJ/d], For bathing, rooms, [MJ/d], Heat load, 2, , [MJ/m • d], Basic unit, , For a kitchen, 2, [MJ/m • d], For bathing, rooms, 2, [MJ/m • d], , Winter, 2640.65, 350.27, 3038.25, 2099.19, 1526.04, 322.85, 1829.42, 850.92, 1134.47, 210.81, 1417.99, 787.53, 0.695, 0.092, 0.800, 0.553, 0.402, 0.085, 0.482, 0.224, 0.299, 0.056, 0.373, 0.207, , Average value, Standard deviation, Maximum value, Minimum value, Average value, Standard deviation, Maximum value, Minimum value, Average value, Standard deviation, Maximum value, Minimum value, Average value, Standard deviation, Maximum value, Minimum value, Average value, Standard deviation, Maximum value, Minimum value, Average value, Standard deviation, Maximum value, Minimum value, , 11, , Summer, 1972.86, 253.74, 2349.91, 1558.10, 1212.32, 91.68, 1320.54, 1065.96, 760.55, 180.04, 1077.47, 492.13, 0.519, 0.067, 0.619, 0.410, 0.319, 0.024, 0.348, 0.281, 0.200, 0.047, 0.284, 0.130, , Facility S, Winter, 2860.08, 1178.97, 4289.83, 1007.28, 1263.74, 422.95, 2062.12, 533.39, 1596.34, 882.14, 2947.87, 338.24, 0.707, 0.292, 1.061, 0.249, 0.313, 0.105, 0.510, 0.132, 0.395, 0.218, 0.729, 0.084, , Summer, 1011.74, 588.29, 1915.18, 250.33, 384.31, 110.94, 572.35, 187.37, 627.42, 518.24, 1486.13, 50.17, 0.250, 0.145, 0.474, 0.062, 0.095, 0.027, 0.142, 0.046, 0.155, 0.128, 0.367, 0.012

Page 15 :

when there was no bathing time., For Summer 1, there were lifter shower and bathing with mechanical bathtubs in, the morning. The bathtub in the day service center is filled with water at 11 am. In, Summer 2, hot water was supplied into bathtubs located on the 1st floor and hot water, was used in the care house bathing room at 10 am. In Summer 3, the bathing room, usage is almost none and water is used only for the kitchen. As above, the hourly, consumption of hot water changes drastically for the each pattern in Facility S so that, Summer 1 and Winter 1 which show high water consumption need to be investigated in, order to collect information regarding the equipment design., 3.4 Heat consumption, Table 7 shows the statistics of hot water heat amount per day in Facility T and, Facility S. As the water source for the hot water supply is different between Facility T, and Facility S, the cold water temperature in Facility T is used for the heat amount, calculation in order to compare the heat consumption in both facilities., As for the hot water heat consumption, Facility T shows average 2640.65 [MJ/d], during winter time and 1972.86 [MJ/d] during summer time. In Facility S, the winter, time and summer time usage are 2860.08 [MJ/d] and 1011.74 [MJ/d], respectively. The, heat amount is significantly reduced during summer time in Facility S., , 4. Conclusion, In this study, the characteristics of cold and hot water usage are clarified by, comparison of both facilities based on the statistics of daily and hourly consumption of, cold and hot water, and supplied heat amount in two seasons., As for the daily total consumption of cold and hot water, the basic units are, approximately the same between two facilities during summer and winter. In the daily, consumption of hot water, the similar tendency in both facilities is obtained, except the, hot water consumption during summer in Facility S, as the purpose of hot water usage, changes. Furthermore, each percentage of the consumption for a kitchen and for bathing, rooms accounts for 50 % respectively in total hot water consumption., In the standard deviation of daily consumption of cold and hot water, the difference, between two facilities is significant. In Facility S, the consumption of hot water varies, day by day, because the usage of the bathing rooms changes on each day. The result can, be confirmed based on the correspondence between the hourly hot water consumption, and the bathing room schedule., , 5 Acknowledgments, The authors wish to express their gratitude for the great cooperation by people who, involved in the nursing homes., , 12

Page 16 :

6 References, 1. T. Itai, et al. (2007). A study on the Energy Consumption of Welfare Facilities for, aged, Part 5 An Analysis of the Loads of Cold and Hot Water Consumption., Proceedings of AIJ Tyugoku Chapter Architectural Research Meeting, Vol. 30, 445448, 2. M. Miyoshi, et al. (2005). A study on the Energy Consumption of Welfare Facilities, for aged, Part 3 Measurement Result of the Cold and Hot Water. Proceedings of AIJ, Tyugoku Chapter Architectural Research Meeting, Vol. 28, 489-492, , 7 Presentation of Author, Daisaku Nishina is an Associate Professor at Gr aduate School of, Engineering, Hiroshima University. His special field is the planning, of water supply system and water environment for people, , 13

Page 17 :

14

Page 18 :

A2) A Study, , on Bathing Behavior and Hot Water Usage, in Nursing Homes for the Aged, A. Takaaze (1), S. Murakawa (1), D. Nishina (1), T. Itai (1), (1)Graduate School of Engineering, Hiroshima University, 1-4-1 Kagamiyama, Higashi-Hiroshima City, 739-8527, Japan, , Abstract, In Japan, the number of elderly people who need care in daily life has been increasing for, the past 30 years and this trend is expected to continue. In order to ensure that they have, comfortable and fulfilling lives, the construction of nursing homes for them and the, introduction of appropriate fixtures into the homes are required., Many elderly people in nursing homes need help when they take a bath. Their bathing, styles are different from people who do not need care. In such homes, a lot of hot water is, consumed in bathrooms and this consumption affects greatly the energy consumption of, the hot water supply system in a whole building. However, the actual conditions of the, consumption and the usage behavior of hot water have not been revealed yet, though it is, important to design the appropriate system in nursing homes. Therefore, the purpose of, this study is to clarify these conditions and analyze the relationship between consumption, and behavior. This is based on the measurements and the observation surveys given in, bathrooms of an actual nursing home which was chosen in the east area of Hiroshima., The quantity and the temperature of cold and hot water in each faucet were measured, continuously for each bathing. At the same time, the actions of elderly people and the, caregivers during the process of bathing were observed and recorded by researchers that, stayed in the rooms. These measurements and surveys were carried out for about a week, in three seasons. Additionally, questionnaires for the aged and the caregivers were, conducted following the period of observational study., In this paper, the behavioral process in which bathing occurred were defined based on the, results of the observation. The time length and the total water consumption of bathing per, capita were clarified and the temperature and the water consumption in each action were, identified., , 15

Page 19 :

Keywords, Assisted bathing, Nursing home, Water consumption, Bathing behavior, , 1 Introduction, Japanese society has been aging because of the declining birthrate and death rate as well, as increasing life expectancy. The number of people who are identified as people who, need public nursing care by elderly care insurance system is also increasing. This, phenomenon raises awareness of people for nursing care systems and nursing care, facilities. People have recently put much emphasis on satisfaction of not only quantity of, facilities but various and high quality nursing care. In recent trend, efficient aggregation, care replaced private care which considered individual cases in many nursing care homes., At the same time, improvement of nursing care facilities and functions becomes, important to give elderly people high quality care services and comfortable life spaces., Many elderly people in nursing homes need help when they take a bath. Their bathing, styles are different from people who do not need care. In such homes, a lot of hot water is, consumed in bathrooms and this consumption affects greatly the energy consumption of, the hot water supply system in a whole building. However, the actual conditions of the, consumption and the usage behavior of hot water have not been revealed yet, though it is, important to design the appropriate system in nursing homes. Therefore, the purpose of, this study is to clarify these conditions and analyze the relationship between consumption, and behavior., , 2 Outline of the investigation, 2.1 Outline of the measurements, Two bathrooms of the nursing home in the east area of Hiroshima were surveyed. One is a, share bathroom, the other is a private bathroom. The floor plans of the bathrooms and the, summary of the facilities which is in the bathrooms are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1., There are three different bathtubs, (a mechanical bathtub, a large bathtub and a small, bathtub) in the share bathroom. Wash spaces are arranged for each bathtub. The private, bathroom has one bathtub for single use. Floor area of private bathroom is one fifteenth of, the share bathroom and it manages to allow two people to come in., The measurements were carried out for about a week each in three seasons. Table 2 shows, the period of the measurements. Figure 2 shows the distribution diagram of cold and hot, water pipes and the position of measuring instruments. In order to figure out cold and hot, water consumption at each shower, flow meters were put in not only main pipes but, branch pipes and measured at 1-second intervals. Temperature sensors were put in the, inside of cold and hot water pipes and measured at 2-second intervals. Warm water made, up of cold and hot water is used at each showerhead or mixed water faucet., Characteristics of the warm water usage are revealed in this paper and it is called water, , 16

Page 20 :

hereinafter., , Shower, , C, D, , Mixed Water Faucet, , b, , Cold Water Faucet, , Large Bathtub, Small Bathtub, a, , 0.2, , A, , 2, , 0 0.5, , Private Bathtub, , Mechanical, Bathtub, , B, , 1, , Share Bathroom, , Private Bathroom, , Figure 1 – Bathroom Plans, Table 1 – Bathroom Facilities, Shear Bathroom, Bathroom Space, , 43.7, , Dressing Space, , 25.3, , Capacity, of Bathtub, , Facilities, , Private Bathroom, 2.8, 3.2, , Mechanical Bathtub, , 560, , Large Bathtub, , 1400, , Small Bathtub, , 900, , Private Bathtub, , 320, , Mixed Water Faucet, , 2, , Mixed Water Faucet, , 1, , Shower connected to mechanical bathtub, , 4, , Shower, , 1, , Shower, , 4, , Cold Water Faucet, , 1, 10:00, 13:30, , Hours, , 12:00, 15:30, , 10:00, , 12:00, , Table 2 – Periods of Measurements, The Period of, Measurements, T, T, , Cold Water Faucet, , Summer, , 5/ 8/ 2006, , Autumn, , 11/ 10/ 2006, , 18/ 10/ 2006, , Winter, , 15/ 12/ 2006, , 22/ 12/ 2006, , M, M, , M, , M, , 11/ 8/ 2006, , Mechanical Bathtub,, 4 showers, Mixed Water Faucet, , Shower A, , M, , Shower B, , Shower, , Mixed Water Faucet a, M, M M, M, , Mixed Water Faucet b, , T T, T, T, , M, , Shower C, , M, M, T, , Private Bathroom, Shower D, , T, , Share Bathroom, , Ho t Wa, ter Supply, Hot, Water, Supply Pipe, Pipe, , M, , Flo w Sen, sor, Flow, Sensor, , Cold Water Supply Pipe, , T, , Temperature Sensor, , Figure 2 – Cold and Hot Water Supply System, , 17

Page 21 :

2.2 Characteristics of bathing styles and elderly people, Observational investigation on the actual bathing situation was carried out in the, bathrooms at the same time of measurements. Respondents to the investigation were, elderly people who used the bathrooms and caregivers who assisted them. The purpose of, this investigation is to classify water consumed in the bathrooms into some uses which, are shown in Table 3. Three main uses of water are bathwater, water for bathing behavior, and cleaning water. In addition, the water for bathing behavior is divided into eight acts, shown in the Table 3. Figure 3 shows an example about a bathing process. The number in, this figure corresponds to the number of each bathing acts in Table 3.Basic bathing, process has the same order as it is shown in Figure 3 regardless of type of bathtub. In case, that elderly people have poor condition, “shower to warm up a body” is carried out in, stead of “soak in a bathtub”. “Wash a body and hair then shower” is carried out for all, elderly people. However, on “shower before washing”, “shower after soaking a body in a, bathtub” were not carried out for all elderly people., Table 4 shows characteristics of elderly people who use the bathtubs. The number of, females is larger than males because females accounts for 80% of the all people in the, nursing home. There is no big difference between average ages. Physical ability of elderly, people is expressed by care level which has a scale of 1 to 5. The meanings of the care, level are shown in Table 5. Figure 4 shows percentages of each level on each bathtub., There is a major gap clearly when one compares mechanical bathtub and the others., According to Figure 4 and Table 5, most mechanical bathtub users tend to depend on the, physical care. They keep laying themselves down on a stretcher by the bathtub during, bathing. The number of caregiver per one elderly person was one or two. At the same time,, large bathtub users and private bathtub users tend to need some help. Some of them are, able to wash their faces, hair and bodies by themselves. However caregivers always, handle a showerhead at any time. The number of caregiver is one per elderly person., According to these conditions, appropriate bathtub is selected for each elderly person in, consideration of care level. Small bathtub bathing is not included on this paper because it, was barely used in the three seasons., Table 3 – Water Uses in a Bathroom, Bathwater, , Water to fill a bathtub full, 1 Shower before washing, 2 Wash a body and hair then Shower, 3 Shower to warm up a body, , Water for Bathing, Behavior, , 4 Shower after soaking a body in a bathtub, 5 The others (wash towel etc.), 6 Soak a body in a bathtub, 7 Wait, 8 Move, , Cleaning Water, , Water to clean a bathtub and a bathroom, , 18

Page 22 :

L/ 2sec., Water Consumption, , 0.6, , Consumption, , 0.5, , 8, , 1, , 2, , 6, , 0.4, , 4, , 8, , 5, , 0.3, 0.2, 0.1, 0, 0, , 2, , 4, , 6, , 8, , 10, , 12, , 14, , 16, , 18, , Time minute, , Figure 3 – Example of a Bathing Process, Table 4 – The Number of Elderly People and Average Age, The Number of People, Male, Mechanical, Bathtub, Large, Bathtub, Private, Bathtub, , Average, Age, , Summer, , 8, , 24, , 87.5, , Autumn, , 10, , 24, , 87.2, , Winter, , 10, , 27, , 87.6, , Summer, , 2, , 7, , 88.3, , Autumn, , 1, , 8, , 89.1, , Winter, , 1, , 7, , 86.5, , Summer, , 2, , 5, , 89.7, , Autumn, , 2, , 7, , 85.3, , Winter, , 1, , 6, , 84.9, , 0%, , 20%, , 40%, , 60%, , 80%, , 100%, , Mechanical, Bathtub, Large, Bathtub, , Summer n=32, Autumn n=34, , Autumn n=9, , Private, Bathtub, , Female, , Winter n=37, Summer n=9, Winter n=8, Summer n=7, Autumn n=9, Winter n=7, Level 1, , Level 2, , Level 3, , Level 4, , Level 5, , Figure 4 – Percentages of each level, Table 5 – The Meanings of the Care Level, Level 1, , Unsteady on feet, Necessary to be assisted with bathing and using rest room, , Level 2, , Unable to stand up or walk by oneself, Necessary to be assisted with bathing and using rest room, , Level 3, , Necessary to be assisted with bathing, using rest room, dressing, etc., , Level 4, , Necessary to be assisted with whole acts included bathing, dressing and eating etc., , Level 5, , Dependent on others' assistance for whole living, Unable to communicate verbally, , 19

Page 23 :

3 Features of daily water usage, This chapter describes daily water usage of three main uses of water; the bathwater, the, water for bathing behavior and the cleaning water. Figure 4 shows daily water, consumption of each uses and the number of elderly people who took a bath. Water, consumption of bathing behavior fluctuates based upon the number of them. Bathwater, consumption of the mechanical bathtub is down by about half on October 12, December, 16, 21. The reason is the mechanical bathtub was used only in the morning on these days, though it was usually used in both mornings and evenings., As for the large bathtub, bathwater consumption increased on a specific date because, water filled in the bathtub is replaced with fresh water once a week. However, in the, winter, hot water needed to be added to keep appropriate temperature because the water, temperature turns down though a circulation system with a boiler was put in. Cleaning, water consumption of the large bathtub is less than the mechanical bathtub’s one., , 2400, , 12, , 1200, , 6, 0, , 0, , Water Cousumption, L/d, , Summer, 2400, , 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18, Autumn, , 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22, Winter, 6, , Large Bathtub, , 1600, , 4, , 800, , 2, 0, , 0, 5 6 7 8 9 10 11, Summer, 600, , The Number of, People, , 5 6 7 8 9 10 11, , Water Cousumption, L/d, , 18, , Mechanical Bathtub, , The Number of, People, , 3600, , 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18, Autumn, , 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22, Winter, 9, , Private Bathtub, , 400, , 6, , 200, , 3, , 0, , The Number of, People, , Water Cousumption, L/d, , As for the private bathtub, water consumption of bathing behavior also fluctuates based, upon the number of people who use the bathtub. On the other hand, bathwater, consumption and cleaning water consumption are stable., , 0, 5 6 7 8 9 10 11, Summer, , Water for Bathing Behavior, , 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18, Autumn, Bathwater, , 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22, Winter, , Cleaning Water, , Figure 5 - Daily Water Consumption, , 20, , The Number of People

Page 24 :

4 Features of water usage for bathing behavior, 4.1 Bathing features per capita, This section describes water usage of bathing behavior per capita. Bathing time, water, consumption and temperature are shown in Table 6. These three items are defined as, hereafter. Bathing time: time from when elderly person enters a bathroom till when he, (or she) exits. Water consumption: amount of water which is used for bathing behavior, for each person. Temperature: weighted mean which is calculated based on quantity of, cold and hot water., On the mechanical bathtub, it takes 24 ~ 26 minutes to take a bath, on the other hand, it, takes less than 20 minutes on the other bathtubs. As for the reasons for difference of the, bathing time, it takes time for the mechanical bathtub users to take a bath because they, completely depend on care giver’s assistance when they enter the bathroom and get into, the bathtub. Other reason is that they take off and put on their clothes in the bathroom,, not the dressing room. The bathing time of each bathtub has shortening tendency from, summer to winter, except private bathtub in autumn., As the water consumption, it shows much the same pattern of the bathing time. In case of, the mechanical bathtub, about 40 liters of water per capita are consumed. On the other, hand, less than 20 liters of water per capita are consumed in case of the other bathtubs., There is not a big difference of temperature despite differences of seasons or types of the, bathtubs., Table 7 shows water consumption of the bathing behavior per capita divided by the, gender and the care level. It is can be seen that females tend to consume water more than, males. This is attributed to physical difference included difference of hair length, etc. On, the care level, elderly people who belong to milder level tend to consume water more than, elderly people who belong to severer care level. Because sometimes elderly people who, belong to milder care level wash their hair or bodies by themselves and it takes time, longer than that caregivers wash elderly people’s hair or bodies., Table 6 – Statistics of Three Elements, Time minute second, , Private, Bathhtub, , Large, Bathtub, , Mechanical, Bathtub, , Summer, , Autumn, , Water Consumption L/capita, , Winter, , Temperature, , Summer, , Autumn, , Winter, , Summer, , Autumn, , Winter, , Average, , 26:36, , 24:52, , 24:29, , 42.4, , 45.2, , 41.0, , 40.9, , 40.9, , 40.8, , Standard deviation, , 06:44, , 07:07, , 07:35, , 15.4, , 17.1, , 12.9, , 1.4, , 1.4, , 1.1, , Max, , 44:05, , 57:56, , 51:42, , 83.6, , 117.5, , 83.8, , 43.5, , 46.5, , 44.2, , Min, , 10:54, , 12:54, , 13:12, , 11.9, , 19.6, , 17.1, , 37.6, , 37.8, , 38.4, , Average, , 19:05, , 17:14, , 16:02, , 30.9, , 26.1, , 27.2, , 41.1, , 41.1, , 40.1, , Standard deviation, , 07:23, , 05:07, , 05:20, , 12.5, , 9.3, , 13.3, , 1.7, , 1.6, , 1.5, , Max, , 33:53, , 29:06, , 25:02, , 57.2, , 48.1, , 66.8, , 44.4, , 44.1, , 43.3, , Min, , 09:33, , 06:58, , 05:52, , 14.7, , 14.7, , 9.0, , 38.0, , 38.6, , 37.4, , Average, , 12:49, , 16:50, , 11:33, , 18.6, , 30.4, , 18.1, , 41.1, , 41.0, , 41.2, , Standard deviation, , 04:48, , 05:53, , 04:50, , 6.8, , 11.8, , 7.8, , 2.5, , 1.7, , 1.7, , Max, , 21:25, , 28:48, , 24:16, , 30.8, , 53.8, , 40.2, , 43.7, , 43.8, , 43.0, , Min, , 04:17, , 05:22, , 06:02, , 10.2, , 13.7, , 12.1, , 35.2, , 37.8, , 38.4, , 21

Page 25 :

Table 7 – Water Consumption by the Gender and the Care Level, Mechanical Bathtub, , Large Bathtub, , Private Bathtub, , Summer Autumn Winter Summer Autumn Winter Summer Autumn Winter, , Gender, , Male, ( ), , 42.0, (16), , 41.2, (21), , 38.9, (23), , 24.4, (2), , 20.3, (3), , 37.8, (1), , 11.0, (2), , 28.0, (4), , 12.2, (1), , Female, ( ), , 42.5, (53), , 46.5, (64), , 41.8, (59), , 31.7, (15), , 27.1, (19), , 27.0, (19), , 19.8, (12), , 31.0, (15), , 18.7, (11), , 1 2, ( ), , (0), , (0), , (0), , 41.3, (6), , 34.5, (4), , 54.3, (2), , 27.9, (2), , 33.2, (7), , 22.0, (4), , 3 4, ( ), , 43.2, (13), , 46.3, (11), , 42.5, (10), , 25.6, (9), , 25.1, (13), , 22.5, (10), , 17.0, (12), , 28.7, (12), , 16.2, (8), , 5, ( ), , 45.4, (45), , 43.3, (60), , 39.9, (51), , (0), , (0), , (0), , (0), , (0), , (0), , Care Level, , measure: L/ capita, (n): the munber of people, , 4.2 Each actions feature, This section describes water usage of each act. Figure 6 shows average values of time,, water consumption and temperature of each act. “Shower before washing”, “wash a body, and hair then shower”, “shower to warm up a body” and “shower after soaking a body in, a bathtub” are shown in the figure at each season. According to Figure 6, time of each act, shows a little shortening trend from summer to winter. On the other hand, time of “soak a, body in a bathtub” tends to be longer in the winter on the mechanical bathtub and the, private bathtub. This is attributed to that caregivers take plenty of time to soak elderly, people in the bathtub in order to warm up a body in consideration of comfortable bathing, because bathroom temperature fall more than eight degrees in the winter compared to the, summer., Water consumption of each act indicates a similar tendency with time of each act. As far, as the private bathtub, water consumption of “wash a body and hair then shower” in the, autumn is larger than the others. According to the record of the observational, investigation, one of caregivers used a lot of water for “wash a body and hair then, shower” and for “the others”. It can be understand that water usage of caregiver affects, water consumption., As far as temperature of each act, seasonal difference is found on the large bathtub and the, private bathtub but there is not so much difference on the mechanical bathtub. Compared, with each act, temperature of water for “shower after soaking a body in a bathtub” tends, to be high, despite differences of seasons or bathtubs., , 5 Conclusions, Investigations are carried out to clarify the actual condition of the usage of water at the, bathrooms in the nursing home. Conclusions are summarized as follows., 1) The consumption of bathwater is greatly affected by a capacity of a bathtub and, , 22

Page 26 :

8, Time minute, Water Consumption L, , Mechanical Bathtub, , 6, , 40, , Private Bathtub, , 4, 2, 0, , 1, , 30, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 6, , Mechanical Bathtub, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 6, , Large Bathtub, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 6, , Private Bathtub, , 20, 10, 0, 44, , Temperature, , Large Bathtub, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 1, , 4, , Mechanical Bathtub, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 1, , Large Bathtub, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 3, , 4, , Private Bathtub, , 42, 40, 38, , 1, , 2, , 3, , 1, , 4, , Summer, , Autumn, , Winter, , Summer, , Autumn, , Winter, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, , 1, , 2, , Shower before taking a bath, Wash a body and hair then shower, Shower fo warm up a body, Shower after soaking a body in a bathtub, Soak a body in a bathtub, , Figure 6 – Average of Three Attributes of Each Act, , 2), , 3), , 4), 5), , number of times of filling a bathtub with water. As room temperature fall down from, summer to winter, the bathwater consumption increases on the large bathtub. And the, number of people influences to the water consumption of bathing behavior. Diurnal, change of the cleaning water consumption is small., The consumption for bathing behavior varies greatly according to types of bathtub. It, means that the care level affects the water consumption. The mechanical bathtub, users who need full assistance consume water more and also take time longer than the, large and the private bathtub users., On the gender, females tend to consume water more than males according to physical, differences including length of hair. As far as the care level, elderly people who, belong to milder level tend to consume water more than people who belong to severer, level., With the shortening of the bathing time from summer to winter, acts at a wash space, tend to shorten. On the other hand, time of “soak a body in a bathtub” is lengthened., The water consumption of each act shows a similar tendency with time of its own., The temperature of each act shows that “wash a body and hair then shower” is little, low and “shower after soaking a body in a bathtub” is little high., , 6 Acknowledgments, The authors wish to express their gratitude for the great cooperation by people who, involved in the nursing homes., , 7 References, 1. T.Itai et al.- A Study on the Loads of Hot Water Consumption of the Bathroom in, Nursing Homes for Aged Part1. Hot Water Consumption in Bathtubs for Different, Style of Care Bathing: Technical Papers of Annual Meeting The Society of Heating,, , 23

Page 27 :

Air-Conditioning and Sanitary Engineers of Japan 2007, 2. A.Takaaze et al.-A Study on the Loads of Hot Water Consumption of the Bathroom in, Nursing Homes for Aged Part2. Questionnaire Results and the Relationship of, Bathing Behavior and Characteristic of Usage of Hot Water: Hot Water Consumption, in Bathtubs for Different Style of Care Bathing: Technical Papers of Annual Meeting, The Society of Heating, Air-Conditioning and Sanitary Engineers of Japan 2007, , 8 Presentation of Author, Akiko Takaaze is the graduate student at graduate school of, engineering, Hiroshima University., 1-4-1, Kagamiyama Hiroshima Higashi-Hiroshima, 739-8527, Japan, , 24

Page 28 :

A3), , Domestic Water Consumption and its Irregularity, , Jüri Säärekõnno, Valdu Suurkask, Tallinn University of Technology, , Introduction, Existing Estonian regulatory documents used for the design of water supply systems, inside buildings do not comprise numerical data, or data is outdated, of water, consumption rates and coefficients describing daily water use., Department of Environmental Engineering of TUT has been involved in drafting the, Estonian Standard of site water supply [1] and this study is continuation of this activity., The task of the present study is to specify actual water consumption rates for various, building structures (apartment buildings with different level of convenience, public, buildings) together with the hour-irregularity ratio in order to revise the current water, consumption rates and design basis for different water supply equipment (reserve tanks,, diaphragm tanks)., The first stage of the study covers water consumption in apartment buildings with most, common type of convenience level (central heating, bath tubs). Later the study will, cover apartment and public buildings with other convenience levels., , Study description, To dimension the domestic water supply system it is necessary to know the water, consumption per day, per hour and per second. For the estimation of the first two values, we proceed from the national domestic water consumption rates., Current domestic water consumption rates were approved in 1993 by the regulation, No.24 of the Estonian Ministry of Environment [2]. The rates presented are relying on, the sanitary convenience level of the building and are actually the result of, “mechanical” (perceptual) reduction of the former Soviet Union rates by 50…100 liters, average per capita per day (see table 1)., , 25

Page 29 :

Levels of convenience of apartments building and corresponding water, consumption rates per resident, Consumption, Building`s level of convenience, Unit, rate,, Q0d, l/d, 1. Water supply and drainage without bath and, 1 resident, 85 (120*), shower, local heating, gas., 2. Water supply and drainage without bath and, shower, local heating, local heat exchangers for „, 200 (250), hot water (several hot water tap units), 3. Apartment buildings with district heating, ,, „, 190 (230), showers., 4. The same, 1500 – 1700 mm bath tubes and, „, 250 (300), showers up to the 12 - storey buildings., 300 (400), 5. The same for the 12 - storey and higher, „, buildings, *) Former Soviet Union rates., European Standard [3] recommends as average daily consumption 143 liters per head, (resident). This value can be used for calculation of annual consumption., The “actual” domestic water consumption studies, conducted by TUT Department of, Environmental Engineering are indicative of a significantly lower value in comparison, with the above rates., The first stage of the study covers water consumption in apartment buildings with the, most common type of convenience level (district heating, bath tubs). Later the study, will cover apartment and public buildings with other convenience levels., The water consumption data have been registered and collected by special logger, arranged in buildings of different type., Based on the 7 year long experience, the mean water consumption of an apartment with, central heating and a shower (with no bath-tub) during the cold period is 102 l/d r (rate, 190 l/d r). The difference is also nearly two-fold. Total water consumption checked in, 113 Mustamäe apartment buildings was also nearly twice smaller than the rates – 127, versus 250 l/d r., Also we have collected data from other sources. For example, based on the data of the, Estonian Union of Co-operative Housing Associations, the average water consumption, of five properly working Tallinn housing associations during the heating season was, 106-108 l/d r (rate 250 l/d r). Thus, it makes two- or even three-fold difference [4]., Domestic hot water consumption (60-70 l/d r) is also significantly smaller ( 38%, average) than the rates (105 l/d r). Last hot water consumption studies, conducted by, TUT in 30 apartment houses located in different parts of the city (number of consumers, varied from 34 to 450 per house), point at even smaller hot water consumption – 34.2, l/d r. i.e. measured amount of consumed water forms, on the average, only 32.5% of the, above hot water rate.[5] Proceeding from the above, application of the current water, consumption rates is resulting in over dimensioning of the water pipes and installations., Thus, to secure optimization of both construction and maintenance costs of the water, supply systems it is essential to have water consumption rates that reflect the actual, water utilization., , 26

Page 30 :

From the design standpoint it is also necessary to know the hour-irregularity ratio,, depending on the convenience level and number of dwellers. As a result of experimental, investigation we have data of water consumption for different time ranges – per week,, per day, per hour. These values are connected with domestic water consumption rates., Analysis of experimental data is not completed yet. For the analysis we have calculated, consumption parameters based on the theoretical equations., One of the characteristics water consumption irregularity is hourly peak coefficient Khm, :, Q, k hm = hm ,, (1), Qhk, where: Qhm – hourly maximum water consumption (m3/h), Qhk – average hourly water consumption, m3/h., In design practice it is rational to determine the relation between the hourly peak, coefficient Khm and type of building it`s level of convenience and number of residents., In the Estonian Standard „Design of site water supply” [ 6 ] the hourly peak coefficient, Khm is rougly determined:, Qhm = khm Qhk = (2,5…10) Qhk., , (2), , Hourly peak coefficient Khm can be calculated using following equations, involving, probability related:, Qhk = Qdm / 24,, , (3), , Where: Qdm – daily peak flow rate, which is calculated:, Qdm = 0,001 Qod U, m3/d, , (4), , Where: Qod – resident`s daily water consumption rate (m3/d r), (tabel 1);, U – residents number., If any one appliance is used on average for a period of t seconds every T seconds, the, probability P of finding it in use at any instant is given by: [ 7,8 ], P=, , t, , or, T, , (5), , P=, , Q0 h ⋅ U, t, =, ,, T 3600 ⋅ Qn ⋅ N, , (6), , Where: T = 3600 s, Qoh – appliance`s hourly draw off flow rate, l/h;, Qn – appliance`s draw off flow rate, l/s;, N – appliances number., , 27

Page 31 :

The hourly probability Ph is calculated by formula:, , Ph =, , 3600 ⋅ P ⋅ Qn1 Q0h ⋅ U, ,, =, Qnh, Qnh ⋅ N, , (7), , Where: Qnh – hourly worst case draw off flow rate, l/h, Hourly peak coefficient Khm calculation example is presented in following table 2., , Table 2, Hourly peak coefficient Khm calculation of 2. level of convenience of apartments, building, No, , 1, , 2-1, , 2-2, , 2-3, , 2-4, , •, , N, , U, peo, ple, , UN, , Qn, 1/s, , Qod, 1/d p, , Qoh, 1/h*, el, , Ph, , Ph*N, , α,, , h, , Qhm, m3/h, , Qdm, m3/d, , 11, , 12, , Qhk, m3/h, , khm, , *, , 2, , 3, , 4, , 5, , 6, , 7, , 8, , 9, , 10, , 10, , 4, , 0,4, , 0,2, , 200, , 9,3, , 0,0234, , 0,234, , 0,480, , 0,480, , 0,900, , 0,375, , 13, 12,79, , 14, , ", , 8, , 0,8, , 0,0416, , 0,416, , 0,621, , 0,621, , 1,600, , 0,667, , 9,32, , ", , 12, , 1,2, , 0,0598, , 0,598, , 0,741, , 0,741, , 2,300, , 0,0958, , 7,73, , „, , 15, , 1,5, , 0,078, , 0,780, , 0,849, , 0,849, , 3,000, , 0,125, , 6,79, , ", , 18, , 1,8, , 0,0962, , 0,962, , 0,949, , 0,949, , 3,700, , 0,154, , 6,15, , 25, , 11, , 0,45, , 0,0234, , 0,585, , 0,733, , 0,733, , 2,250, , 0,0938, , 7,82, , ", , 21, , 0,84, , 0,0437, , 1,092, , 1,017, , 1,017, , 4,200, , 0,175, , 5,81, , ", , 31, , 1,23, , 0,0640, , 1,600, , 1,261, , 1,261, , 6,150, , 0,256, , 4,92, , ", , 40, , 1,62, , 0,0842, , 2,105, , 1,481, , 1,481, , 8,100, , 0,338, , 4,39, , ", , 50, , 2,00, , 0, 04, , 2,600, , 1,639, , 1,639, , 10,00, , 0,417, , 3,93, , 50, , 22, , 0,45, , 0,0234, , 1,170, , 1,056, , 1,056, , 4,500, , 0,188, , 5,65, , ", , 42, , 0,84, , 0,0437, , 2,185, , 1,515, , 1,515, , 8,400, , 0,350, , 4,33, , ", , 62, , 1,23, , 0,0640, , 3,200, , 1,917, , 1,917, , 12,30, , 0,512, , 3,74, , „, , 81, , 1,62, , 0,0842, , 4,210, , 2,285, , 2,285, , 16,20, , 0,675, , 3,38, , ", , 100, , 2,00, , 0,1040, , 5,200, , 2,561, , 2,561, , 20,00, , 0,833, , 3,07, , 200, , 90, , 0,45, , 0,0234, , 4,68, , 2,449, , 2,449, , 18,00, , 0,750, , 3,26, , „, , 16, , 0,84, , 0,0437, , 8,740, , 3,749, , 3,749, , 33,60, , 1,400, , 2,68, , „, , 246, , 1,23, , 0,0640, , 12,80, , 4,933, , 4,933, , 49,20, , 2,050, , 2,41, , „, , 324, , 1,62, , 0,0842, , 16,84, , 6,050, , 6,050, , 64,80, , 2,700, , 2,24, , „, , 400, , 2,00, , 0,1040, , 20,80, , 7,098, , 7,098, , 80,00, , 3,333, , 2,13, , αh , Qoh, Qnh values are taken from the tables and diagram [8]., , 28

Page 32 :

As comparison the mean value of the irregularity ratio – 2.06 (1.65…2.75) was, estimated in 2006 on the basis of 35 measurement cycles., , Conclusion, The experimental data of current study proves the necessity of the renewal national, regulations of domestic water consumption flow rates. Additionally for the, measurements in Estonian capital Tallinn we should perform the corresponding, investigation in other towns., Proposals for updates in Estonian Standard, Design of site water supply, will be done, after the analysis of experimental data of actual water consumption in apartment, buildings is completed., , References, 1. Valdu Suurkask, Jüri Säärekõnno New Design Codes for Plumbing Systems in, Estonia. 1999 CIB W62 Symposium Edinburg, Water Supply and Drainage for, buildings., 2. Olmevee tarbimisnormid. Keskkonnaministeeriumi määrus nr. 24, 28.09.93, 3. EVS-EN 806-3:2006 Specifications for installations inside buildings conveying, water for human consumption – Part:3 Pipe sizing, 4. J. Säärekõnno. Siseveevõrkude hüdraulilisest arvutamisest. Keskkonnatehnika, 1999, 3, pp.10-11, 5. Kõiv, T.-A. and Toode, A. Heat energy and water consumption in apartment, buildings. Proc. of Est. Acad. Sci. Eng. 2001, 73, 235-241., 6. EVS 835:2003. Kinnistu veevärgi projekteerimine. Design of site water supply., 7. A.F.E. Wise and J.A. Swaffield. Water, Sanitaary and Waste Services for, Buildings. Butterworth-Heinemann 2002. pp. 4-10, 8. П.П. Пальгунов, В.Н. Исаев. Санитарно-технические устройства и, газоснабжение зданий. Москва, Высшая школа 1982.pp. 140-150, p.377, , 29

Page 33 :

30

Page 34 : Domestic hot water consumption in Estonian, apartment buildings, , A4), , Alvar Toode1 and Teet-Andrus Kõiv1,

[email protected], 1, Tallinn University of Technology, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Department of, Environmental Engineering, Estonia, , Abstract, Domestic hot water consumption trends in Estonian apartment buildings are presented., Changes in domestic hot water consumption profile are shown. Measuring results show, that actual maximum consumption values are substantially less than design values. A, new formula for calculating the domestic hot water load for dimensioning instantaneous, heat exchangers is recommended. The influence of the new calculation method of, dimensioning and operating costs of district heating network is presented., , Keywords, Hot water consumption, consumption profile, heat exchangers, investments and, operating costs of district heating network., , 1 Introduction, For optimal dimensioning of hot water heating equipment and systems, it will be, necessary to know the actual domestic hot water consumption and the consumption, profile. Such investigations have been carried out in the USA, Great Britain and other, countries [1, 2, 3]., These investigations show that domestic hot water consumption is influenced by, different aspects. The investigation carried out in Great Britain shows that domestic hot, water consumption is influenced by the age of people, the number of children in the, family, the income of the family, the number of persons in the family, etc [3]., The first research on domestic hot water consumption in residential buildings of Estonia, was made in Tallinn in the years 1973-1974 [4]. In the former Soviet Union [5], the domestic hot water consumption in residential buildings was relatively high:, 95 l/d per person or more on an average., , 31

Page 35 :

2 Domestic hot water consumption and consumption profile, Table 1 - Domestic hot water consumption (l/d⋅per person) in the investigated, apartment buildings, 1999, , 2000, , 2001, , 2002, , 2003, , 2004, , Average, , 60, , 56, , 49, , 46, , 45, , 44, , Ranges, , 34…77, , 44…71, , 38…66, , 37…59, , 35…56, , 36…58, , High domestic hot water consumption lasted until the nineties of the last, century. The main reason for that was the low cost of water and heat, energy. The latest investigations [6, 7] show an essential decrease in, domestic hot water consumption in the nineties and at the beginning of, 2000, Table 1. Within these 6 years the decrease in domestic hot water, consumption was 26% in investigated apartment buildings. The share of, domestic hot water in total water consumption was 46% and was, approximately the same in the 6 years., The comparison of the weekly consumption data, l/(m2⋅d), in 1974 and, 2005 can be seen in Fig.1. During this period domestic hot water, consumption l/(m2⋅d) in apartment buildings has decreased more than three, times., , Figure 1- Domestic hot water consumption on week-days and the average domestic, hot water consumption per week during the years 1974 and 2004. (The area is the, general area of apartments)., , 32

Page 36 :

l/d per person, , 65, 60, 55, 50, 45, 60-70%, , 71-80%, , 81-90%, , 91-100%, , Rate of water meters, , Figure 2 –The influence of the number of water meters in apartments on domestic, hot water consumption in 1999., The main reasons for a decrease in domestic hot water consumption are:, – consumption metering in apartments and payment by real consumption, Figure 2;, – high cost of water and heat and continued tendency of increase;, – extensive renovation of domestic hot water systems, including circulation, renovation;, – use of modern water saving equipment (taps, showers)., Domestic hot water consumption profile in apartment buildings was investigated in, 1974 using an experimental data logging system and in 2005 using impulse water, meters which were connected with data loggers. The collection of the water, consumption data by loggers of different apartment buildings was made during a week., During the 30 years considerable changes in people’s life-style have taken place. To, prove it daily consumption profiles of two apartment buildings in 1974 and 2005 are, presented in Figures 3 and 4., 2500, , litres, , 2000, 1500, 1000, 500, 0, 1, , 3, , 5, , 7, , 9, , 11, , 13, , 15, , 17, , 19, , 21, , 23, , Time, , Figure 3 - Consumption profile of a 90-apartment building in 1974 (on Monday), At present the daily consumption is characterized with the morning maximum value,, (Fig.4), which is more close to the consumption profile in West European countries [8]., , 33

Page 37 :

litres, , 500, 450, 400, 350, 300, 250, 200, 150, 100, 50, 0, 0, , 2, , 4, , 6, , 8, , 10, , 12, , 14, , 16, , 18, , 20, , 22, , 24, , Time, , Figure 4 - Consumption profile of a 30-apartment building in 2005 (on Tuesday), , 3 Maximum consumption and new load calculation formula, In Estonia domestic hot water is usually heated by instantaneous heat exchangers. For, dimensioning them it is necessary to know the level of the maximum domestic hot, water consumption. Investigations carried out show that a considerable decrease in hot, water consumption has reduced the actual maximum consumption values when, compared with values calculated by standard [9], Figure 4., 700, 600, 500, , kW, , 400, , 300, 200, 100, , 1, , 10, , 20, , 30, , 40, , 50, , 60, , 70, , 80, , 90, , 100 110 120 130 140 150 165, , Number of apartments, By formula (2), , Measured 2005, , EVS/D1, , Figure 4 - The results of the domestic hot water heating load calculated by, recommended formula (1) and by the EVS method together with the results based, on measured values, On the bases of measured values of domestic hot water maximum consumption a new, formula for calculating the domestic hot water load Φ for dimensioning instantaneous, heat exchangers was derived:, , 34

Page 38 :

Φ = 30 + 15 ⋅ 2 ⋅ n + 0.2 ⋅ n, , (1), , where, n is the number of apartments., Formula (1) is used for apartments with one bathroom and a kitchen in the apartment., If hot water temperature is other than 55°C, correction coefficient must be used:, for temperature 60°C – 1.1 and, for temperature 65°C – 1.2., , 4 Influence of the new calculated load on dimensioning pipes and, operation costs of, district heating network, The same domestic hot water load (formula 1) is used for dimensioning the equipment, of the heat substation and district heating network pipes. As the load calculated by, standard differs 2 times or more from the one calculated by the new method it is, interesting to show the results of dimensioning the diameters of pipes and the operation, costs, As an example a calculation was carried out for a tree form network with 8 consumers,, Fig. 5., , Figure 5 Scheme of district heating network: T1…T8 consumers, To take into account the probability of hot water consumption for the dimensioning of, the pipes of the network, the designed value of domestic hot water for different, segments of the network is calculated by, , y= 0.1878x0.4041, , (2), , where, x is the number of apartments served by the segment of the network, y is the designed, value l/s of, domestic hot water., Pipe diameters for different segments of the network were determined by a hydraulic, calculation. If domestic hot water loads were calculated by the EVS standard, the, diameters of the segments of the network varied from 40 to 125 mm. In using the new, , 35

Page 39 :

domestic hot water load calculation method the diameters of the segments of the, network decreased, the new values varying from 32 to 80 mm., The overall heat losses of the network are calculated by [9] the following formula (3), ⎛ t1 + t 2, ⎞, W/m, − ta ⎟, 2, ⎝, ⎠, and the thermal energy for heat losses by, , (3), , ϕ = 2 ⋅ (U 1 − U ting ) ⋅ ⎜, , n, , Q = τ ∑ ϕ i ⋅ li / 10 6, , MWh, , (4), , 1, , where, φ is special heat losses, W/m,, U1 is overall heat transfer coefficient of pipe, W/(m2K),, Uting is heat transfer coefficient between flow and return pipes, W/(m2K),, t1 is design temperature for flow pipe, °C,, t2 is design temperature for return pipe, °C,, ta is ambient temperature °C,, l is length of segments, m,, τ is operation time of network, h., n is number of segments with different diameters., Pumping costs for district heating network are calculated by [10], thousand kroons, C = P·τ·Ce/1000, kWh, P = H·q·9.81·/(3.6·ηp·ηm), , (5), (6), , where, C is pumping costs,, P is the pumping consumption, kW,, τ is running time in hours,, Ce is price of electricity for one kWh,, H is pump head in meters WG,, q is water flow in l/h,, ηp is pump efficiency,, ηm is motor efficiency., Heat losses and pumping costs are calculated for a period of 40 years, increase in, electricity and the cost of thermal energy was taken 3% per year., The results of the calculation for district heating network are presented in Table 2., , 36

Page 40 :

Table 2 Calculation results for district heating network, Cost of pipes,, million kroons, 5.23, , Heat losses and pumping, costs, million kroons, 30.3, , Calculation by new method, , 3.79, , 27.8, , Decrease in cost, , 1.44, , 2.5, , Decrease %, , 28%, , 8%, , Calculation by standard, , We can see that the new domestic hot water load calculation method and taking into, account the probability of hot water consumption in dimensioning pipe diameters of, different segments give an essential reduction of investments for district heating, network – 28%. At the same time decrease in operating costs is 8% (the decrease in the, cost of heat losses is 14%)., , 5 Conclusions, Domestic hot water consumption in Estonian apartment buildings during the last 30, years decreased more than 3 times (l/d per m2). The main reasons for a decrease in, domestic hot water consumption are: consump- tion metering in apartments and, payment by real consumption, the high cost of water and heat and a continued, tendency of increase, extensive renovation of domestic hot water systems., Great changes in domestic hot water consumption profile have taken place, in recent, years the daily consumption is characterized by the morning maximum value unlike by, the evening maximum value in the years 1970-1985., As the results of measuring show that the actual maximum consumption values are, substantially less than the designed values, a new formula for calculating the domestic, hot water load for dimensioning instantaneous heat exchangers is recommended., An analysis was carried out to determine the influence of the new calculation method on, dimensioning the pipes and the costs of operating the district heating network. The, results showed that for a tree form network the decrease in investments was 28% and, the decrease in operating costs 8%., , Aknowledgements, The authors are grateful to the Ministry of Economy and Communication for supporting, the investigation., , 37

Page 41 :

6 References, 1. Bouchelle, M., Parker, D., Anello, M. Factors Influencing Water Heating Energy, Use And Peak Demand In A Large Scale Residential Monitoring Study. The, Symposium on Improving Building Systems in Hot and Humid Climates, San Antonio,, TX, May 15-17, 2000., 2. Home Energy Magazine Online July/August 1996, http://homeenergy.org/archive/hem.dis.anl.gov/eehem/96/960713.html, 3. Estimates of hot water consumption from the 1998 EFUS, 2005., http://www.dti.gov.uk/files/file16568.pdf, 4. Kõiv, T.-A. Experimental research of hot tap water consumption profiles in dwellings, of Tallinn. Proc. TPI, 1977, No 420, 35-42 (in Russian)., 5. Borodkin, J.D., Dvoretskov, N.G. Profile of domestic hot water consumption in, residential buildings and influence of the control of heat supply. “Teplosnabzhenie, gorodov”, Nautshnye trudy AKH imeni K.D.Pamfilova, 1973, No 95, 49-52 (in, Russian)., 6. Toode,A., Kõiv, T.-A. Domestic hot water consumption investigation in apartment, buildings. Proc. Estonian Acad. Sci. Engng., 2005, 11, 3, 207-214., 7. Kõiv, T.-A., Toode, A. Heat energy and water consumption in apartment buildings., Proc. Estonian Acad. Sci. Engng., 2001, 7, 3, 235-241., 8. P.Sonne. Peak shaving. News from DBDH (Danish Board of District Heating). 1994,, No 1., 9. P.Randlov. District heating Handbook. European District Heating Pipe Manufactures, Association, Denmark, 1997., 10. R. Petitjean. Total Hydronic Balancing. Tour & Andersson AB, Sweden, 1994., , 7 Presentation of Authors, Teet-Andrus Kõiv is the professor at the Tallinn University of, Technology, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Department of, Environmental Engineering He is head of the chair of heating and, ventilation. His specializations are Heat Supply among which Hot, Water Supply; Indoor Climate and Air Conditioning., , Alvar Toode is a PhD student at the Tallinn University of, Technology, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Department of, Environmental Engineering. His research theme is, domestic hot water consumption, consumption profile and, calculation methods., , 38

Page 42 : A study on the loads of hot water consumption, in houses with the hot water storage tank system, (Part 1) An analysis of the hot water usage and the, loads of hot water consumption, A5), , Naoki Yamamoto(1) Saburo Murakawa(2) Hiroshi Takata(3), Hiroki Kitayama(4) Yasuhiro Hamada(5) Minako Nabeshima(6), (1)

[email protected], (2)

[email protected], (3)

[email protected], (4)

[email protected], (5)

[email protected], (6)